Nicholas Nickleby and the Yorkshire schools

Since the 18th century, parents had been sending their children to notoriously brutal Yorkshire boarding schools. Here Professor John Sutherland examines the depiction of these schools in Charles Dickens’s ‘social problem novel’, Nicholas Nickleby.

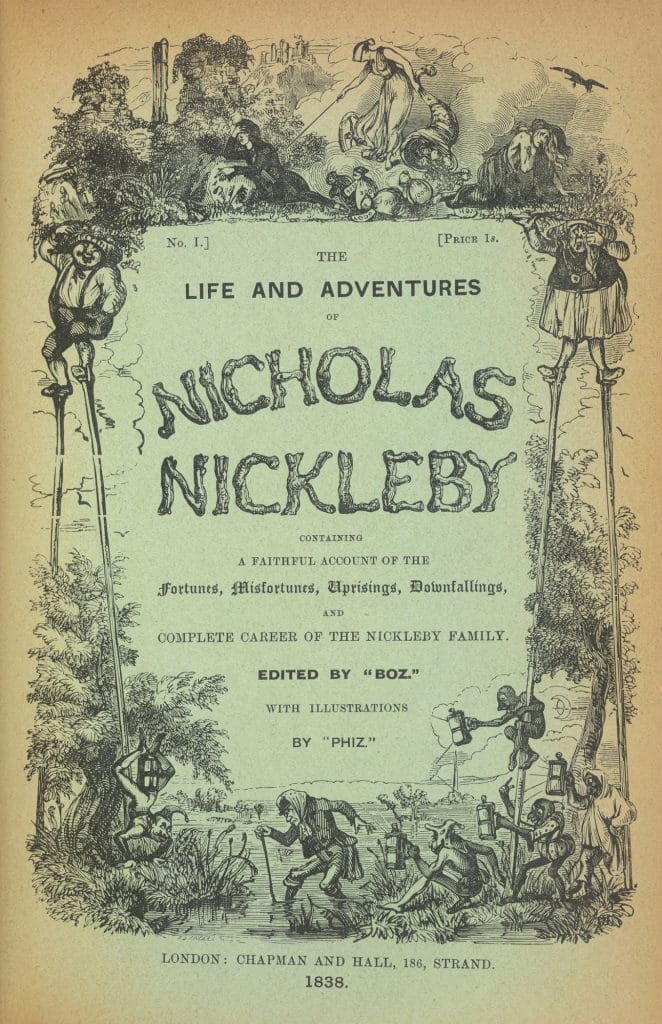

Nicholas Nickleby was Charles Dickens’s third full length novel, and his second in ‘numbers’ (i.e. 20 paper-wrapped, monthly, 32-page, parts, costing one shilling per part, each with two full-page etchings).

The novel was serialised between March 1838 and September 1839 (each issue dated a month later).

Monthly serialisation was a mode of publication which Dickens had pioneered, to huge success, with The Pickwick Papers a couple of years before.

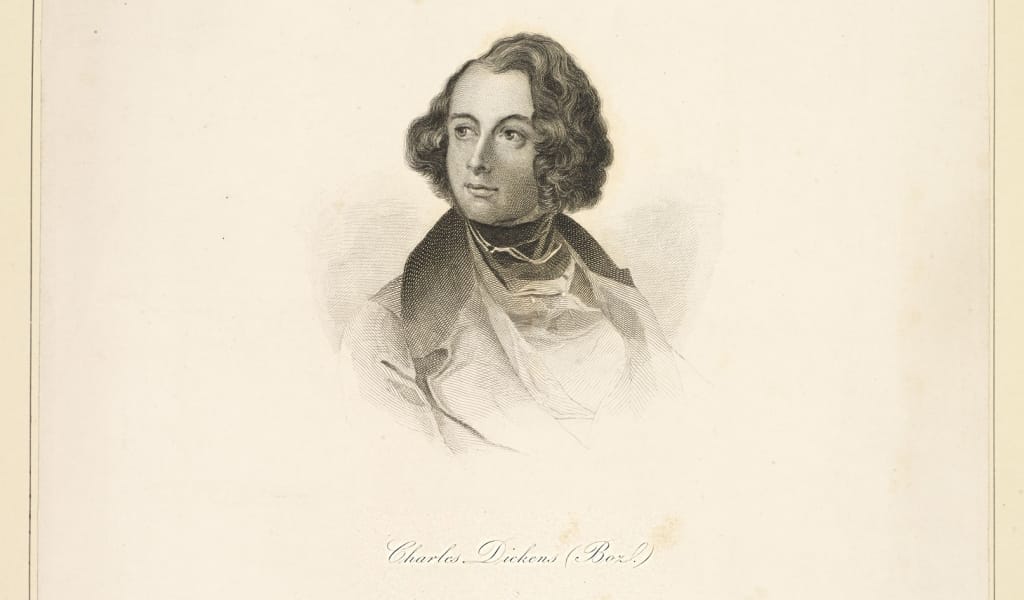

Dickens (born 1812) was, astonishingly, still in his twenties when he wrote Nicholas Nickleby. The famous portrait of Dickens painted by Daniel Maclise, actually created during the composition of Nickleby, captures his youthfulness and the good looks which were regularly commented on.

A haphazard writer

This was the period of Dickens’s life when, as he later said, he was going up ‘like a rocket’. Pickwick had been a wholly comic novel, loosely put together and large parts of it hastily improvised. ‘Boz’ (the pseudonym he used at this stage of his career) was still something of a haphazard writer when he wrote Nickleby. Carefully constructed works would come later in the mid-1840s. If you look at the above cover, for example, it is clear that the author did not, when he began publishing in March 1838, have much idea where the plot would end up 18 months later.

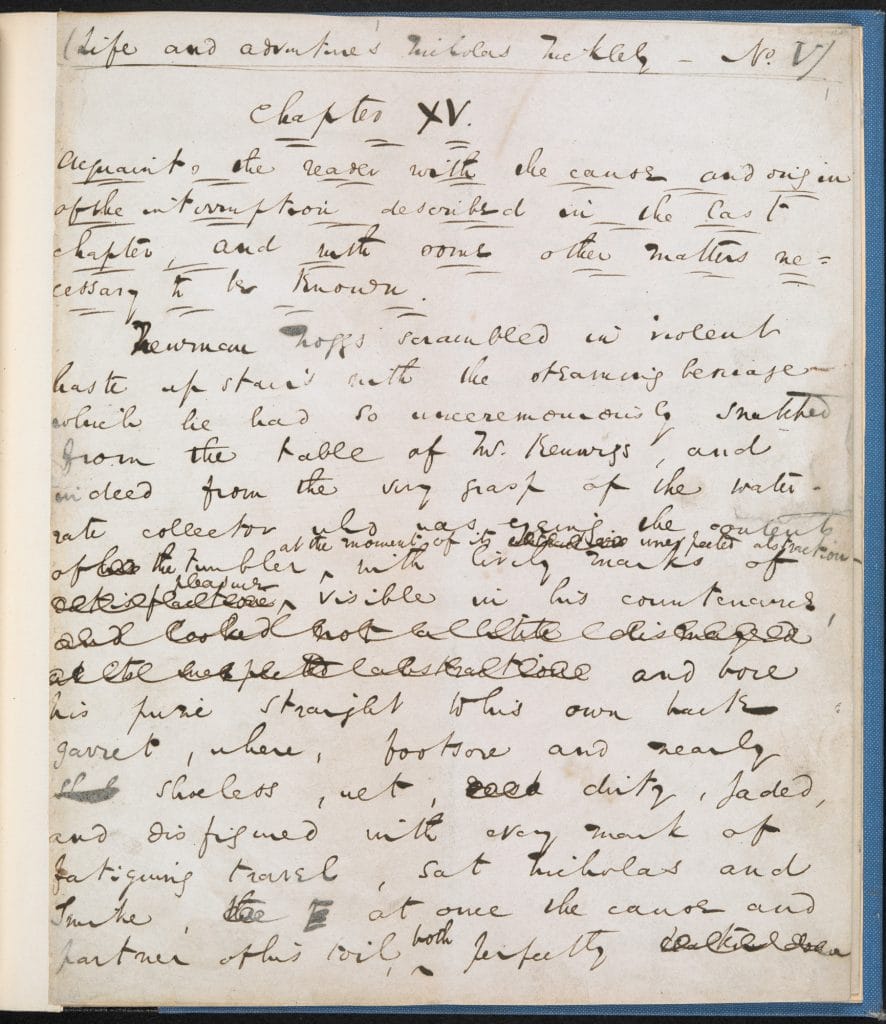

Another pressure on narrative construction was that, capitalising on his unprecedented success, Dickens had put his name to too many contracts, with eager publishers for future novels and journalistic commitments. He was in danger, as he said, of ‘busting the boiler’. It’s nice to think one can detect that ‘rush’ in the look of the manuscript itself.

The ‘social problem’ novel

Between Pickwick and Nicholas Nickleby, Dickens had published Oliver Twist in the magazine Bentley’s Miscellany, of which he was the editor (another heavy call on his time). His story of the foundling boy was a ‘novel with a purpose’ specifically targeting the poor-law act of 1834 and the scandalous cruelties of the workhouse system. It was not merely a bestseller, it ‘changed hearts’ and even government thinking.

Dickens realised, with Oliver Twist, that the novel, in his hands, could make the world a better place. Thus was born the so-called ‘social problem’ novel. Dickens’s reforming target in Nicholas Nickleby is the Yorkshire boarding school industry – places even more inhumane, we are to understand, than the public workhouse described in Oliver Twist.

Yorkshire and the railway revolution

Nicholas Nickleby is set in the mid-1820s, 15 years earlier than its publication. Dickens antedated many of his stories. But here the date is historically significant. Yorkshire at the period of the novel’s action was a kind of British Siberia. From the 18th century, abusive parents had been dumping their unwanted offspring at cheap boarding schools there. It was all about to change, just at the period Dickens was writing Nicholas Nickleby. Railways, from the late 1830s to the 1860s would network the country. The age of the stagecoach was over, the age of the railway coach began. Nicholas Nickleby is, historically, on the cusp of this revolution. Yorkshire, thanks to steam, would soon be a few hours, not days away. It was no longer remote.

As momentous was the introduction of the penny post introduced in 1839, along with the iconic ‘penny black’, the world’s first adhesive postal stamp.

These revolutions were happening as Dickens was writing Nicholas Nickleby. He sets his novel safely back in time from them.

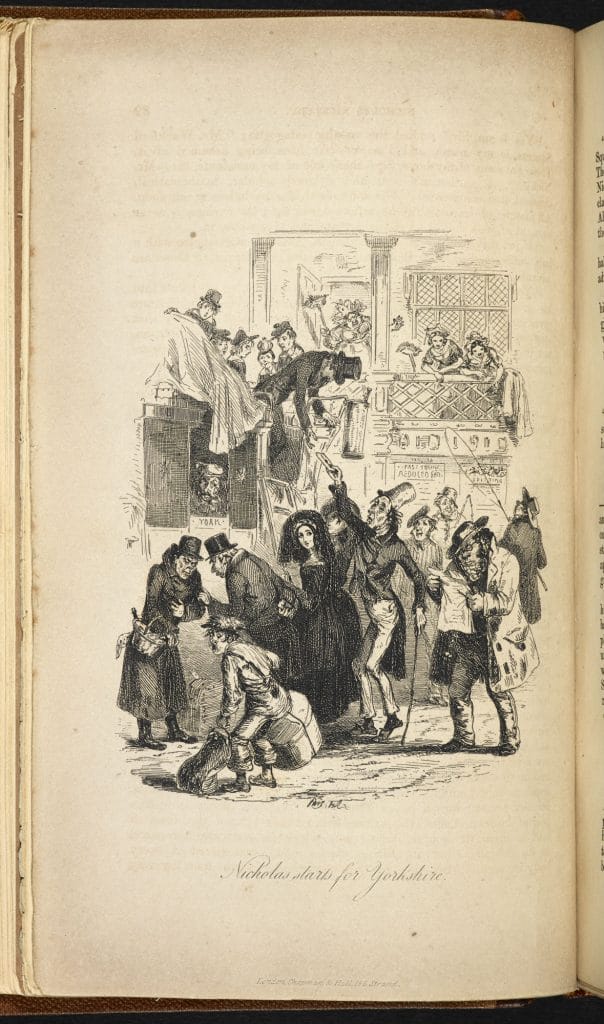

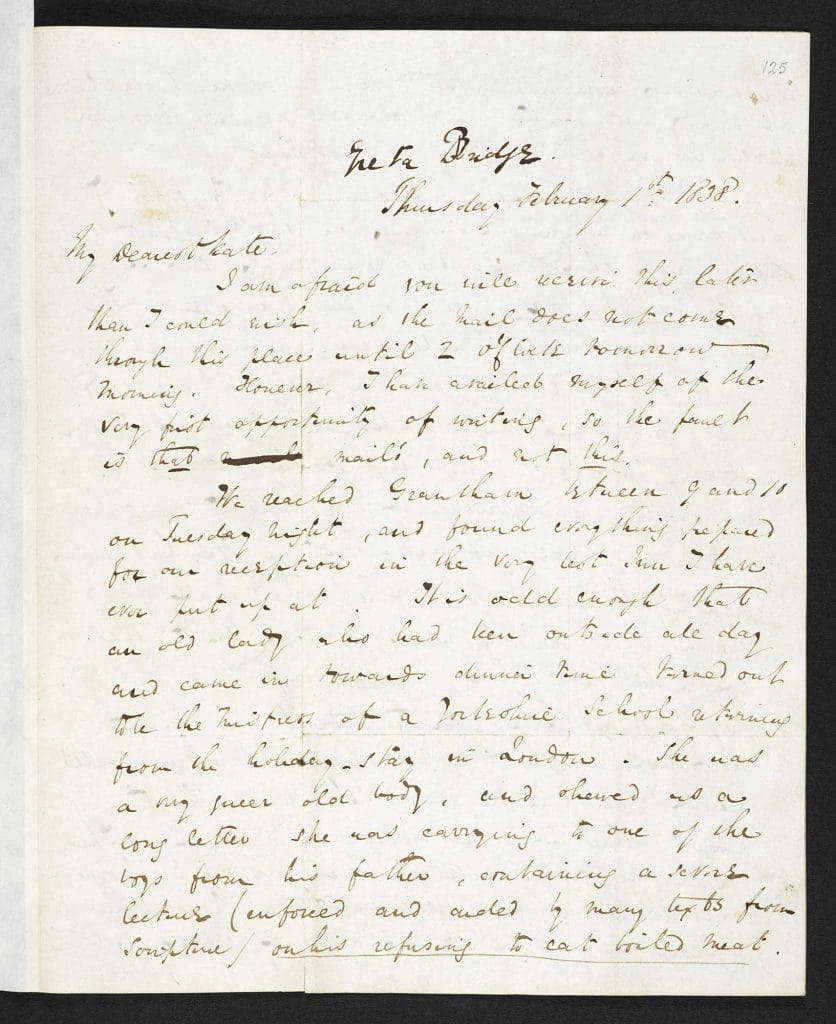

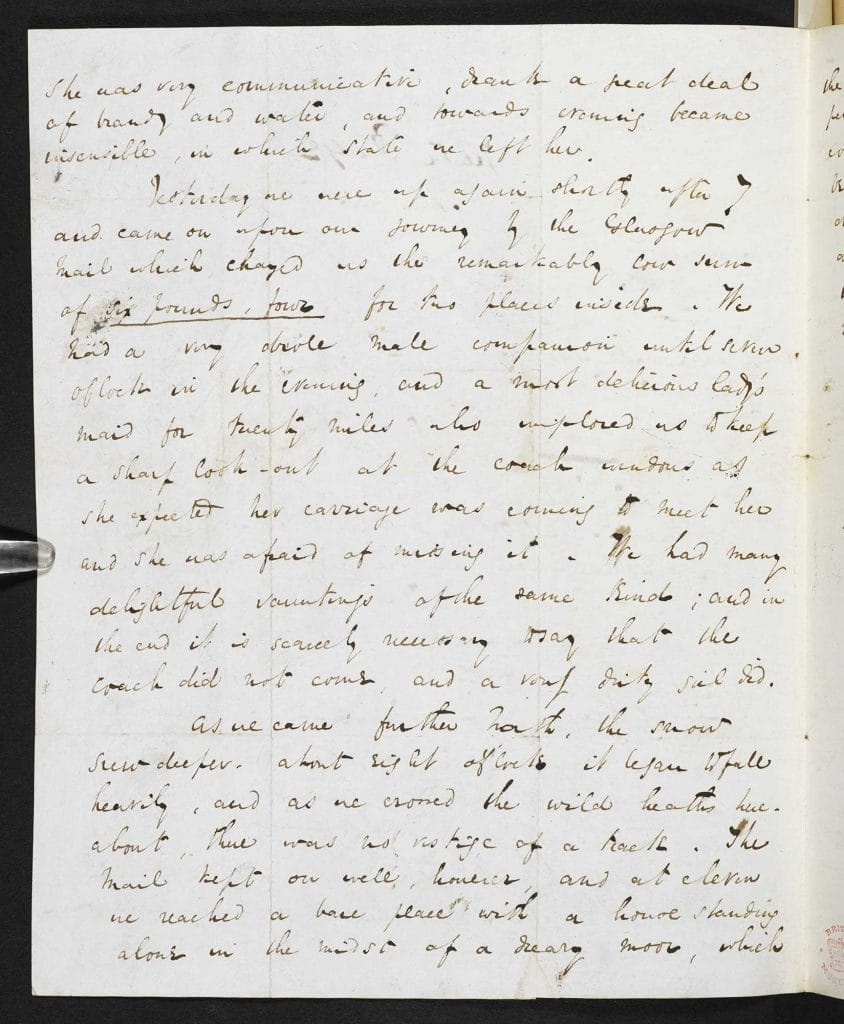

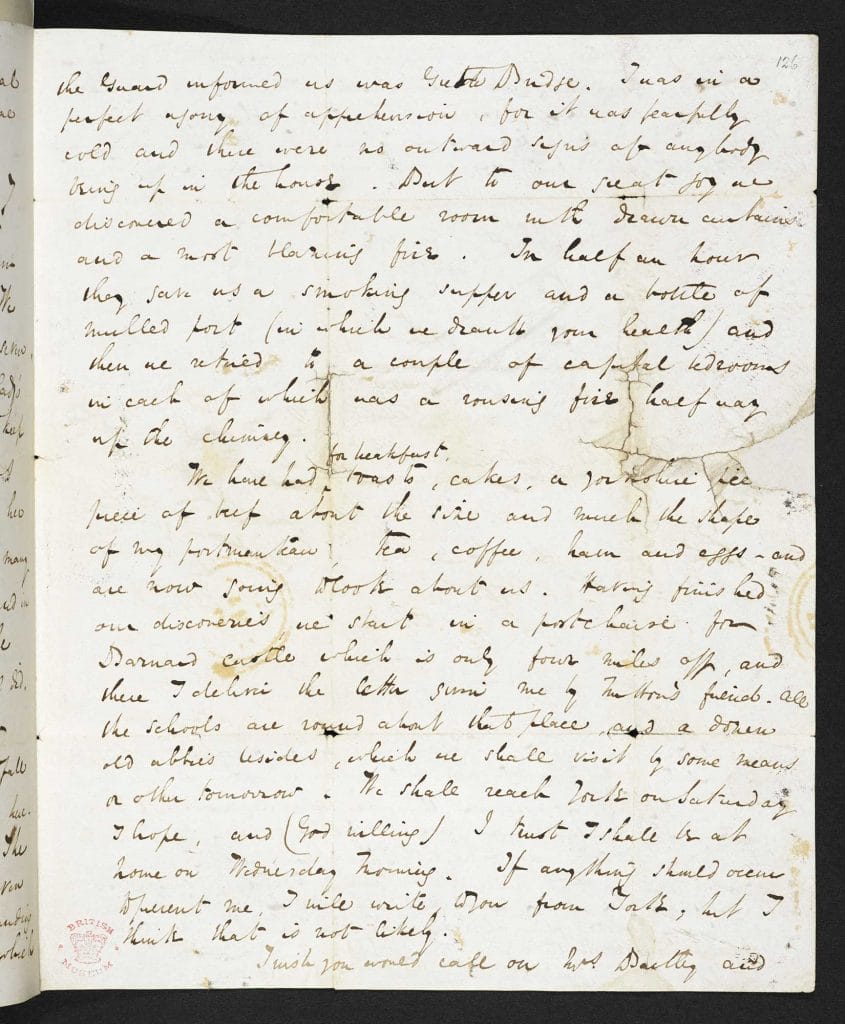

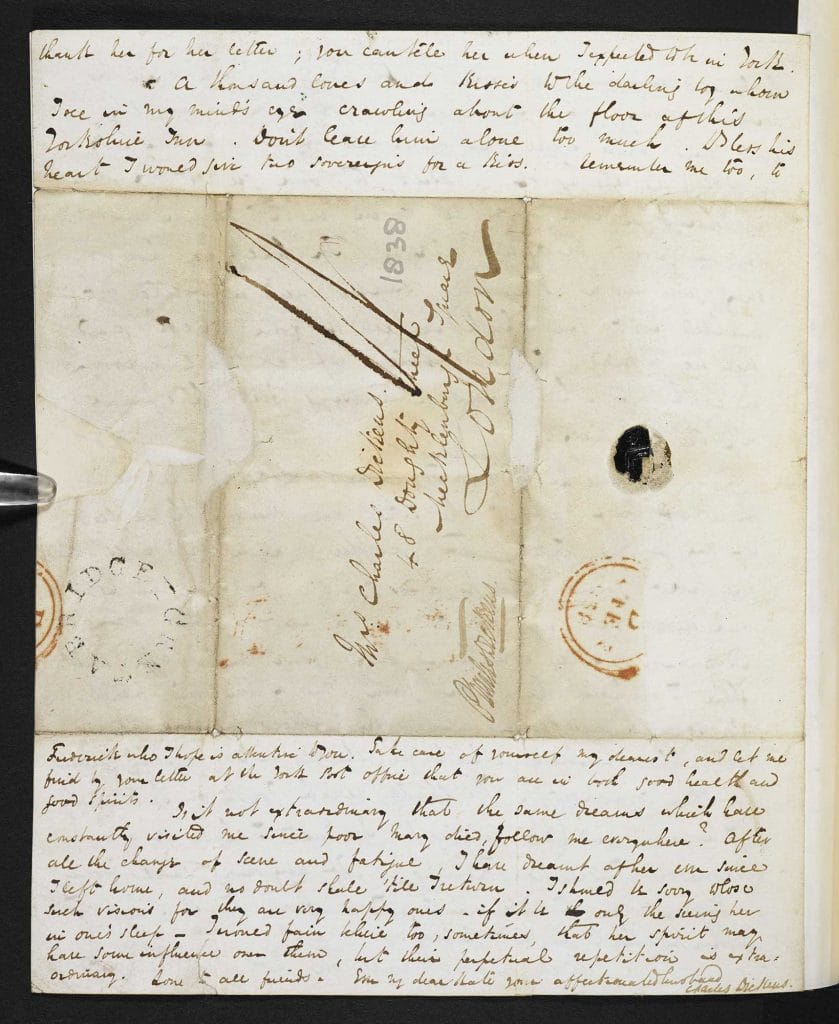

For purposes of research, Dickens undertook a journey to Yorkshire in February 1838, shortly before monthly publication of his novel began. He went by stagecoach (he loved the old way of travel), and gives a vivid description of the trip, thinly fictionalised, in Chapters 5-6 of the novel. He wrote an amusing letter on the subject to his wife and instructed his illustrator (‘Phiz’ – like ‘Boz’, a pseudonym) to create a picture of a stage-coach about to make the arduous journey north.

Plot summary

Nicholas Nickleby, despite recent stage, TV, and film adaptations remains among the less read of Dickens’s works. A brief summary of the plot will help (skip it if you know the novel):

The Nickleby family are left destitute by the death of the father of the family, an amiable farmer also called Nicholas, like his 19-year old son. Nicholas Jr applies to his uncle, Ralph Nickleby, a rich money lender for help. Little help is offered. Pretending to assist (in fact his motives are vicious) Ralph arranges for Nicholas to take up work as an usher (junior teacher) in a Yorkshire boarding school, Dotheboys Hall, at £5 a year. The headmaster and owner, Wackford Squeers, is revealed to be a money-grubbing sadist. Nicholas, a handsome and noble spirited young man, rejects the overtures of Squeers’s repellent daughter and befriends Smike, a pupil brain-damaged by Squeers’s brutality. Nicholas is provoked into thrashing Squeers, in front of all the school, and escapes with Smike back to London. He supports himself, for a while, with the theatrical company of Vincent Crummles, and subsequently takes up clerical employment with the amiable Cheeryble brothers. His younger sister, Kate, has been apprenticed to a dressmaker, Madame Mantalini. Ralph Nickleby (who revels in Nicholas degradation, which he has engineered) encourages a sensual nobleman, Sir Mulberry Hawk, to seduce Kate. Mrs Nickleby is entirely ineffectual in protecting her daughter. But Nicholas fights off the lecherous peer and sets up his womenfolk in a respectable home. He meanwhile falls in love with Madeline Bray. The wholly villainous Ralph has his own plans to marry Madeline off to a disgusting old moneylender, Gride. Smike dies of tuberculosis contracted at Dotheboys Hall, and is revealed to be Ralph’s son. Nicholas is aided by his uncle’s clerk, Newman Noggs, and together they foil Ralph, who hangs himself. Nicholas, now rich, marries Madeline and Kate marries one of the Cheerybles’ nephews. Squeers is sentenced to transportation to Australia.

As the summary indicates, there are three centres of interest. One is London, where the fates of the Nickleby women, mother and daughter hang, precariously, in the balance. The other is Dotheboys Hall. The third is the world of the travelling theatre.

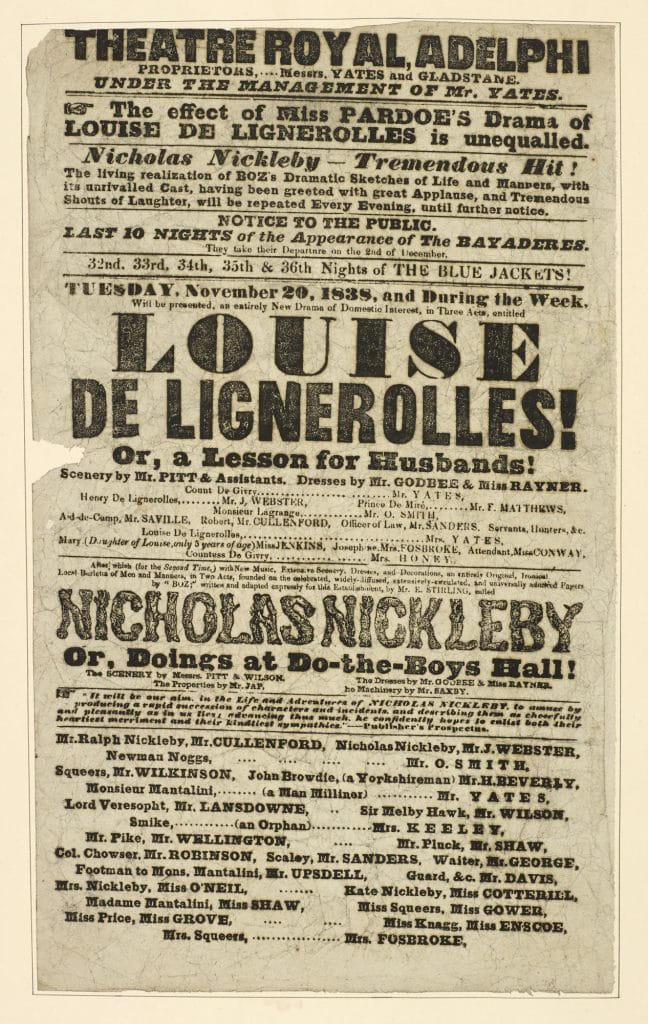

The last had a personal significance for the author. Dickens had himself once longed to be an actor, and throughout life was an avid theatre goer, dramatist, and amateur performer. But at the time of writing Nicholas Nickleby, Dickens was irritated, beyond measure by the fact that theatres in London were putting on unauthorised adaptations of his work, including this one in 1838 (‘Doings at Do-the-Boys Hall’) by the London Adelphi.

Investigating Yorkshire schools

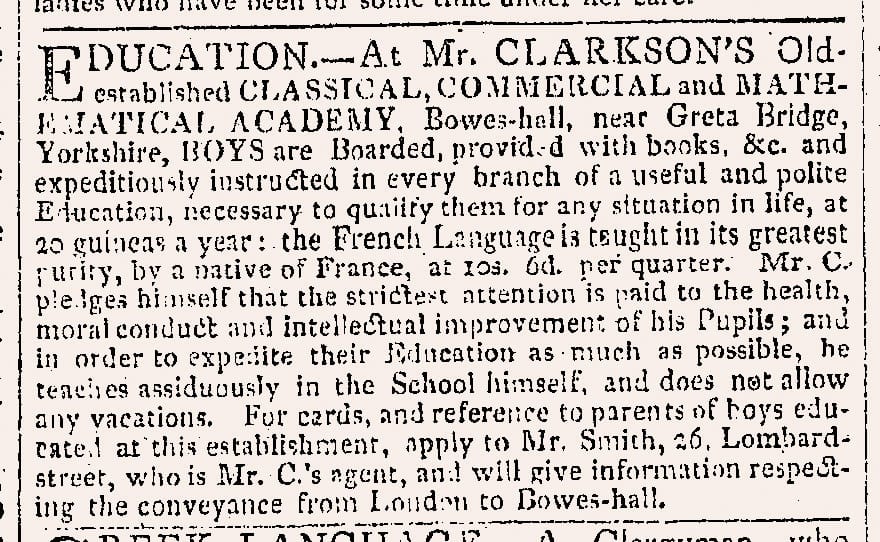

In launching his attack on Yorkshire schools Dickens had clearly been struck by advertisements in the London papers, particularly one, in The Times:

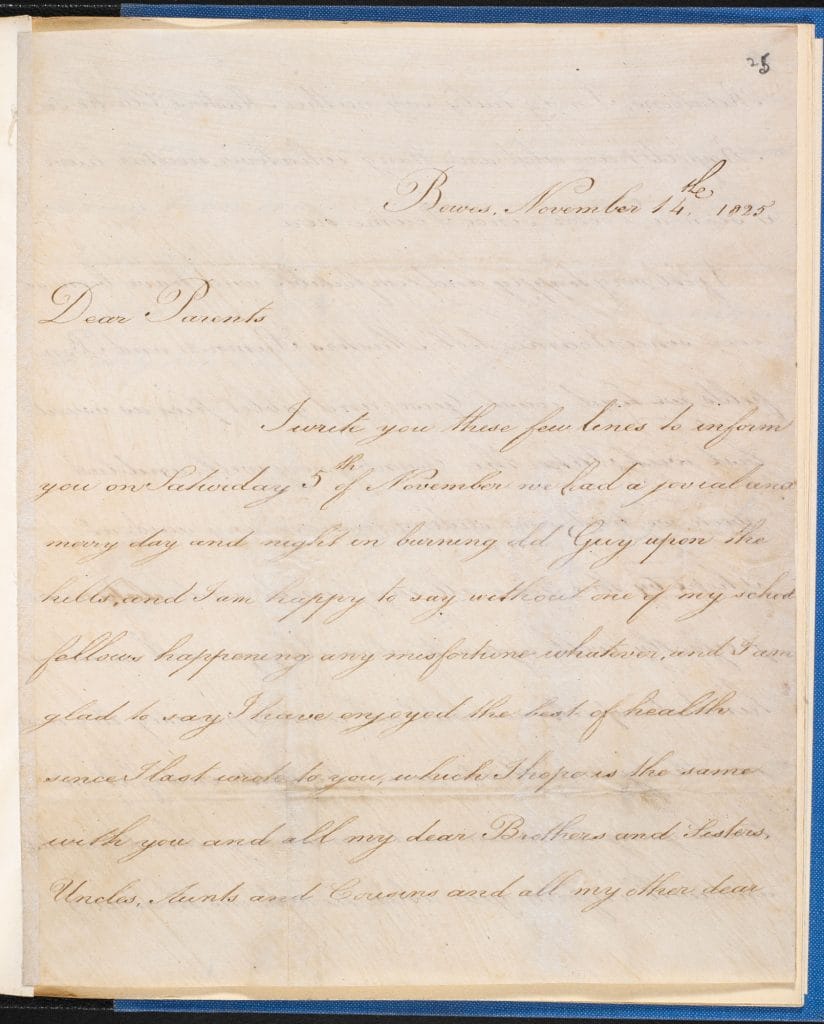

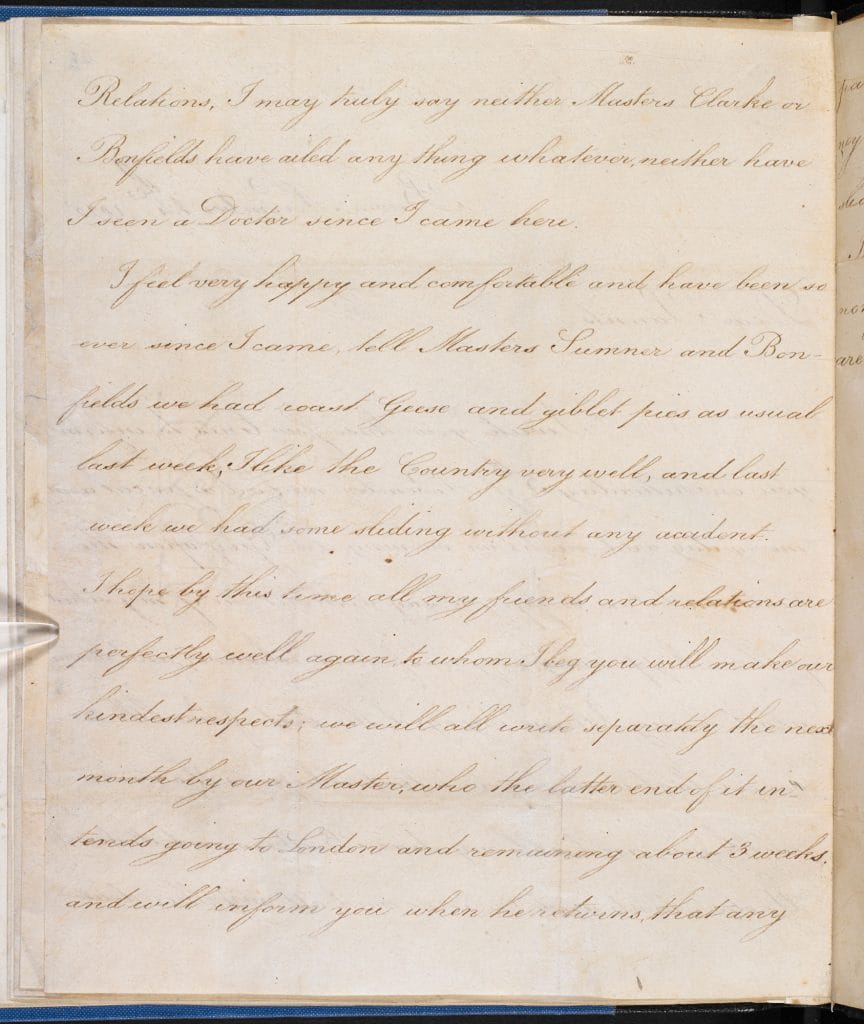

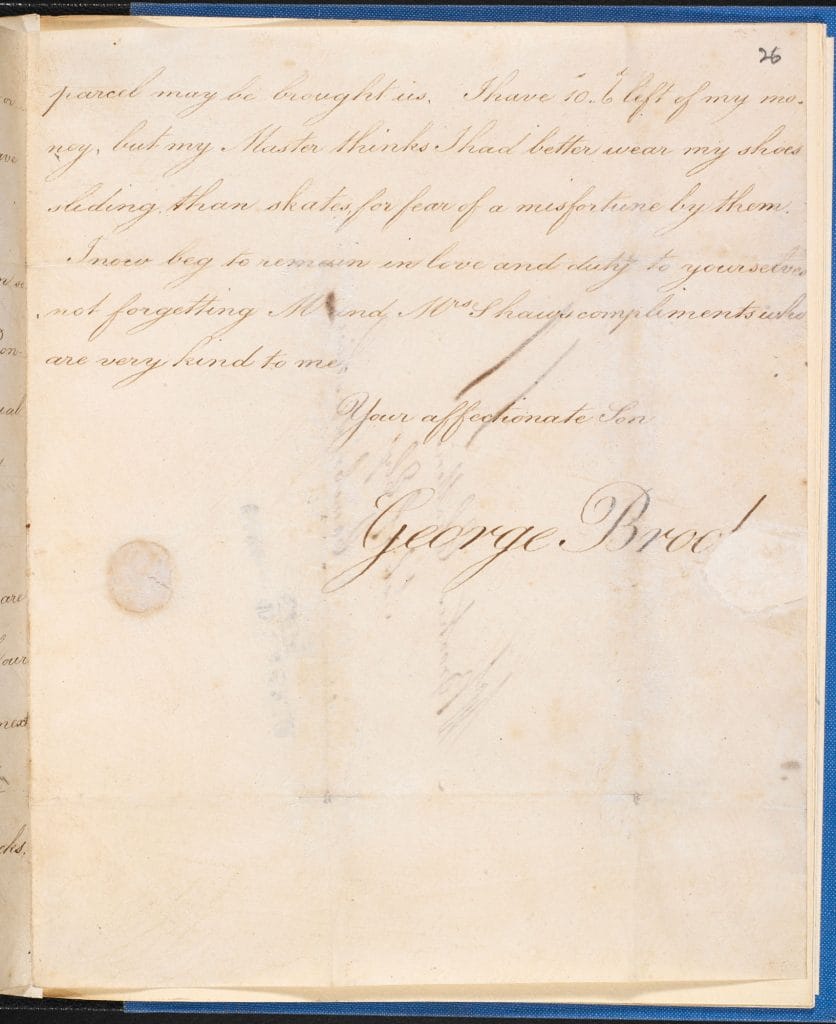

Dickens reproduces this advertisement, almost verbatim, in chapter 3. Note the detail about ‘no vacations’ – i.e. ‘put him on the stage coach and forget the little fellow for good’.On his February 1838 trip Dickens made a particular point (without revealing what he had in mind) of visiting a teacher, William Shaw, the owner, for 20 years, of the above Bowes Hall Academy (in fact a converted, modestly sized, house). Shaw had only one eye – as, of course, does Wackford Squeers. The similarities, as Dickens portrayed them, do not finish there. Squeers had become notorious in 1823, when eight neglected boarders, in his care, went blind. He was convicted of gross negligence, and fined a huge £600 damages. But the school carried on abusing its luckless boarders for profit. Dickens clearly read the court reports, and incorporated elements into his novel, e.g. this, from one of Shaw’s luckless pupils, called ‘William’, doomed to a lifetime of blindness:

Every other morning we used to flea the beds. The usher used to cut the quills, and give us them to catch the fleas; and if you did not fill the quill, you caught a good beating. The pot-skimmings were called broth, and we used to have it for tea on Sunday; one of the ushers offered a penny a piece for every maggot, and there was a pot-full gathered: he never gave it them.

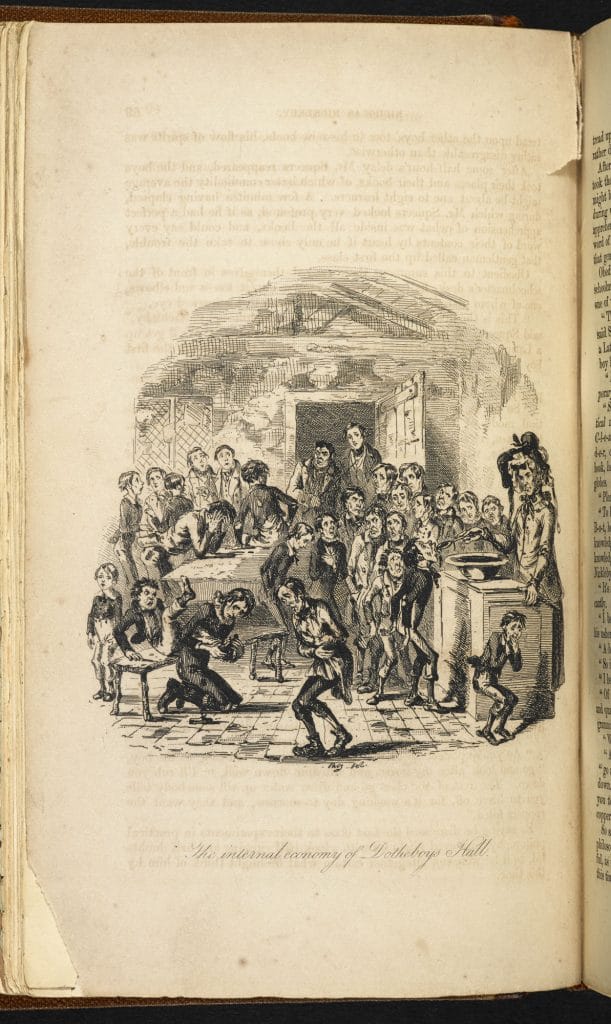

Dickens instructed Phiz to show the full horrors of Bowes Hall/Dotheboys Hall:

Nicholas Nickleby was instrumental in destroying the Yorkshire School industry. Bowes Hall went out of business, as did other establishments of its kind, in 1840.

Descendants of Shaw have argued that Dickens’s representation is unfair. And Shaw was certainly not transported, as he is in the novel. He had made enough money – by marriage, property speculation, and his infamous school – to live as a locally respected man of means, dying at the age of 67. A fine gravestone commemorates him in the village of Bowes.

One could object that in attacking Yorkshire schools Dickens was going for low-hanging fruit. There were, it is estimated, less than a thousand children victimised by the industry in 1839. By contrast, it was not until 1842 (a couple of years after the publication of Nickleby) that Parliament finally got round to passing the ‘Mines Bill’, prohibiting the employment of women and children under the age of ten underground. There were many thousands of them in the coalmines of Yorkshire.

But to have helped save any number of Smikes from the likes of Squeers, England should be forever grateful to ‘Boz’ and his novel.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: John Sutherland

John Sutherland is Lord Northcliffe Professor Emeritus at UCL. He has taught principally in the UK, at the University of Edinburgh and UCL, and in the US at the California Institute of Technology. He has written over thirty books. Among his fields of special interest are Victorian Literature and Publishing History. He is a well known writer and reviewer in the British and American press.