William Blake and 18th-century children’s literature

Julian Walker looks at William Blake’s poetry in the context of 18th-century children’s literature, considering how the poems’ attitudes towards childhood challenge traditional ideas about moral education during that period.

The 18th century saw the development of children’s literature as a genre: by the middle of the century it had become a profitable business. William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience look superficially like traditional 18-century verse for children. But, in fact, the poems challenge and overturn many of the ideas and conventions contained in children’s literature, exploring complex ideas about childhood, morality and religion.

What kinds of books for children were produced during this period, and how does Blake’s work relate to them?

Various types of children’s literature developed from a diverse range of sources. Emblem books, in which animals were used as the basis for moral instruction – animals such as the lamb or tiger were ‘read’ as having symbolic meaning. These developed into natural history books.

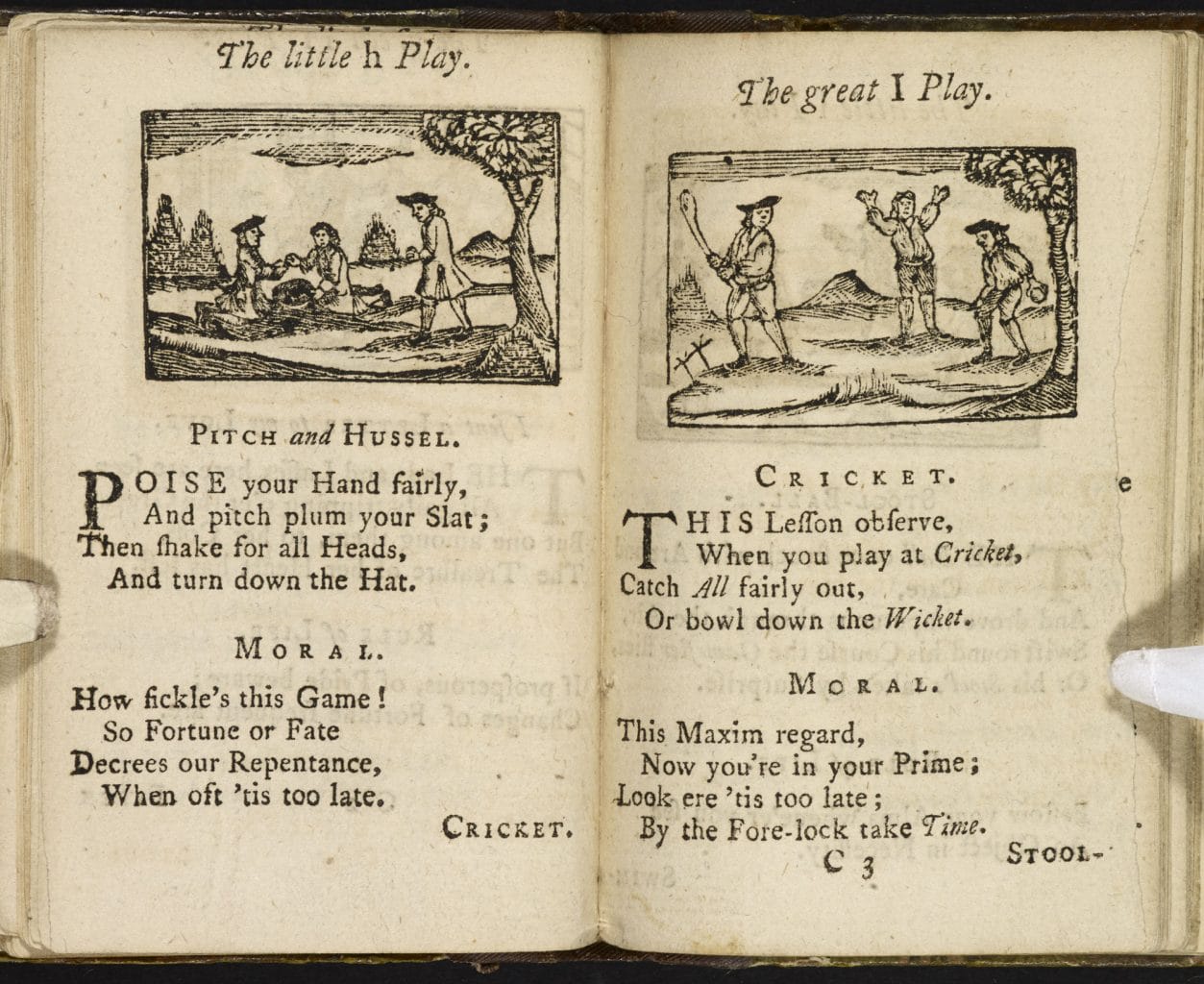

School hornbooks, displaying both the alphabet and Biblical texts on a wooden paddle covered with transparent horn, developed into simple alphabet and counting books, and later into spelling and grammar textbooks and other instructional books, such as the Little Pretty Pocket Book (1744) detailing games, history, or natural history.

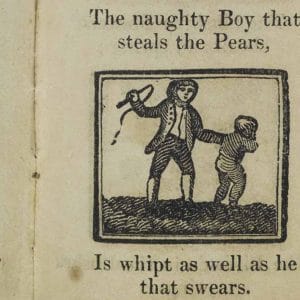

Chapbooks were very small, anonymous and cheap works that were hawked round the country by pedlars. They typically included crude woodcut prints, sometimes hand-coloured, illustrating simple alphabets, counting songs, fantastical tales and imaginative nursery rhymes. They often lacked a clear moral message, instead telling tales of other worlds, implausible characters and often violent events. Even such apparently simple rhymes as ‘Rock-a-by-baby’ and ‘Jack and Jill’ involve random injuries to children.

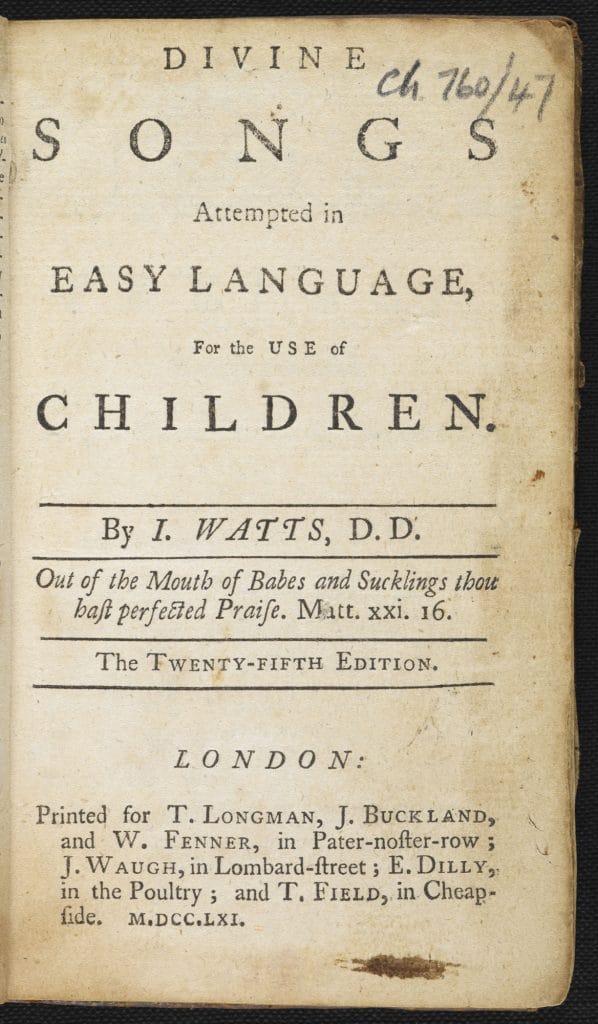

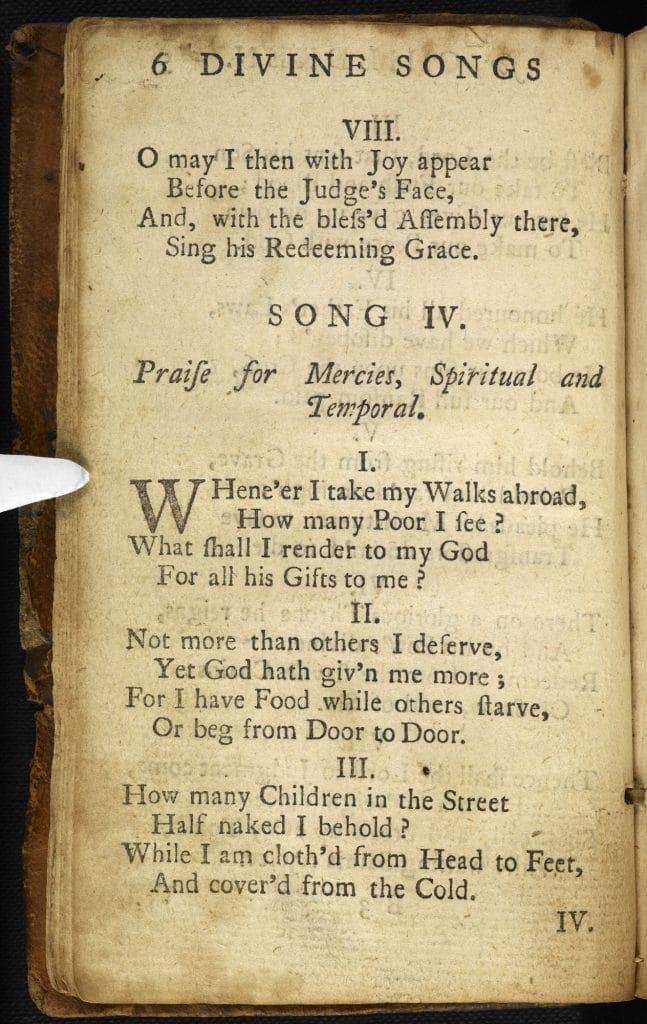

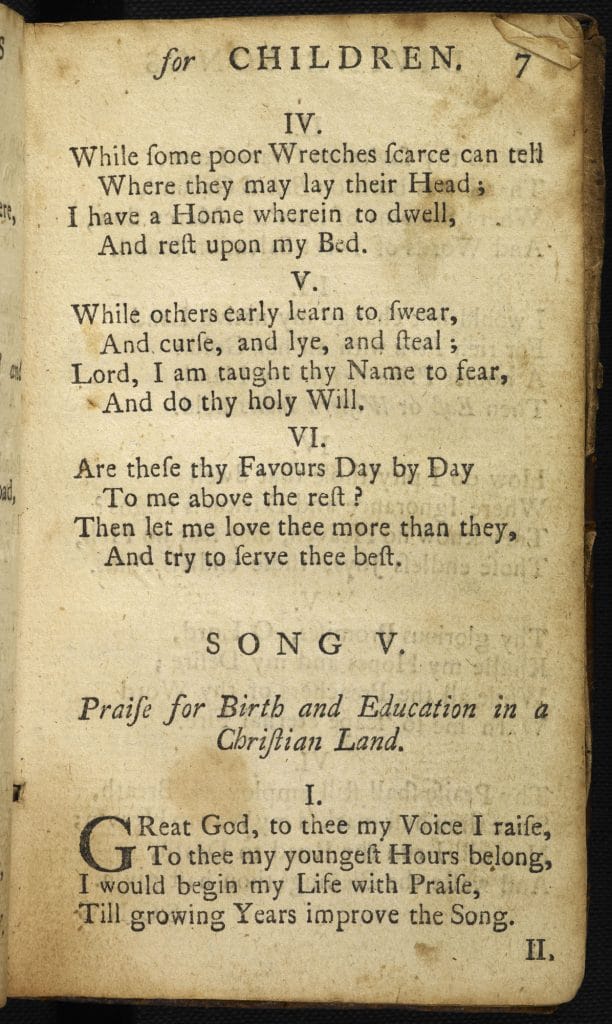

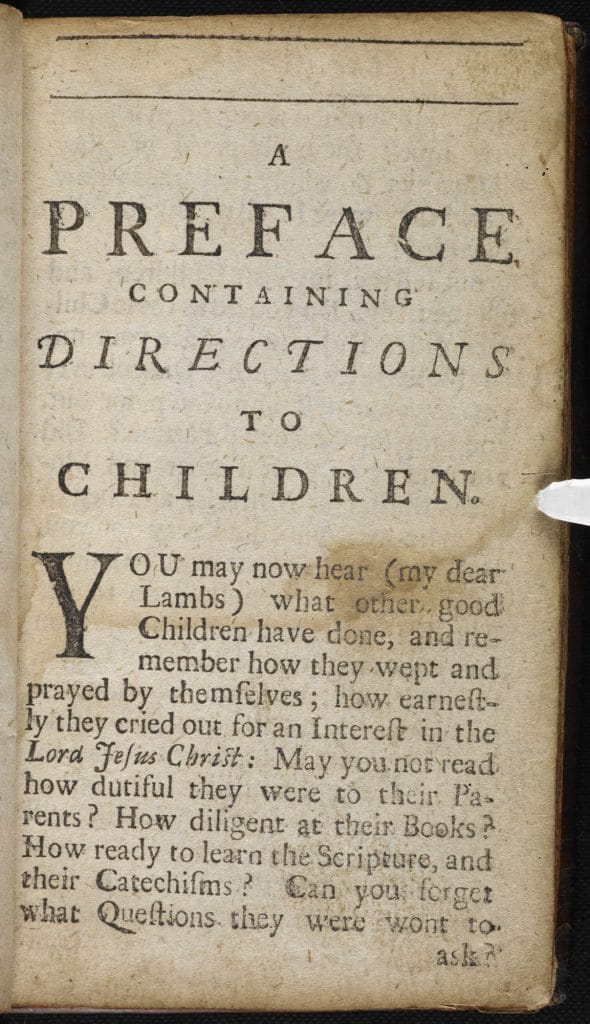

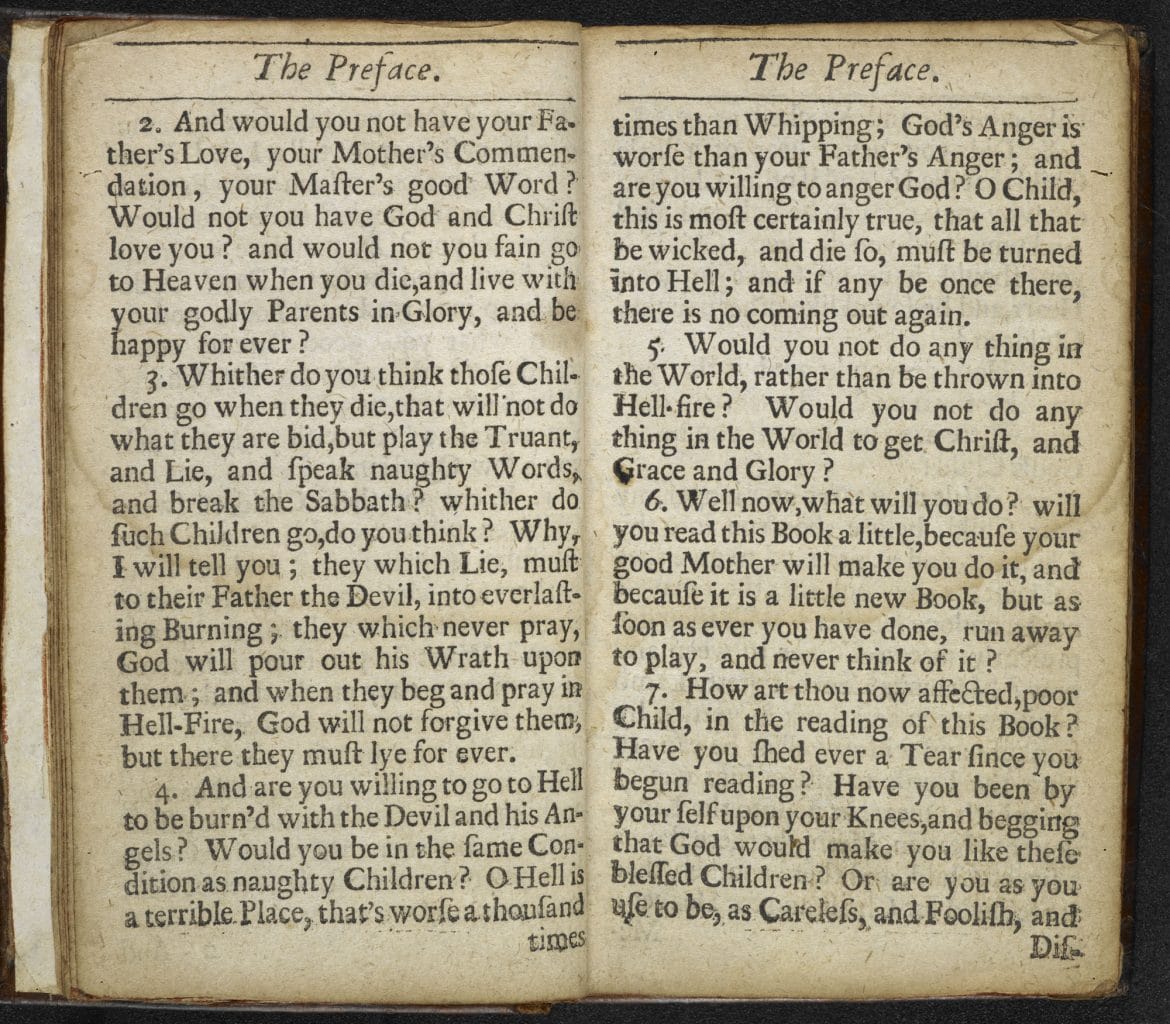

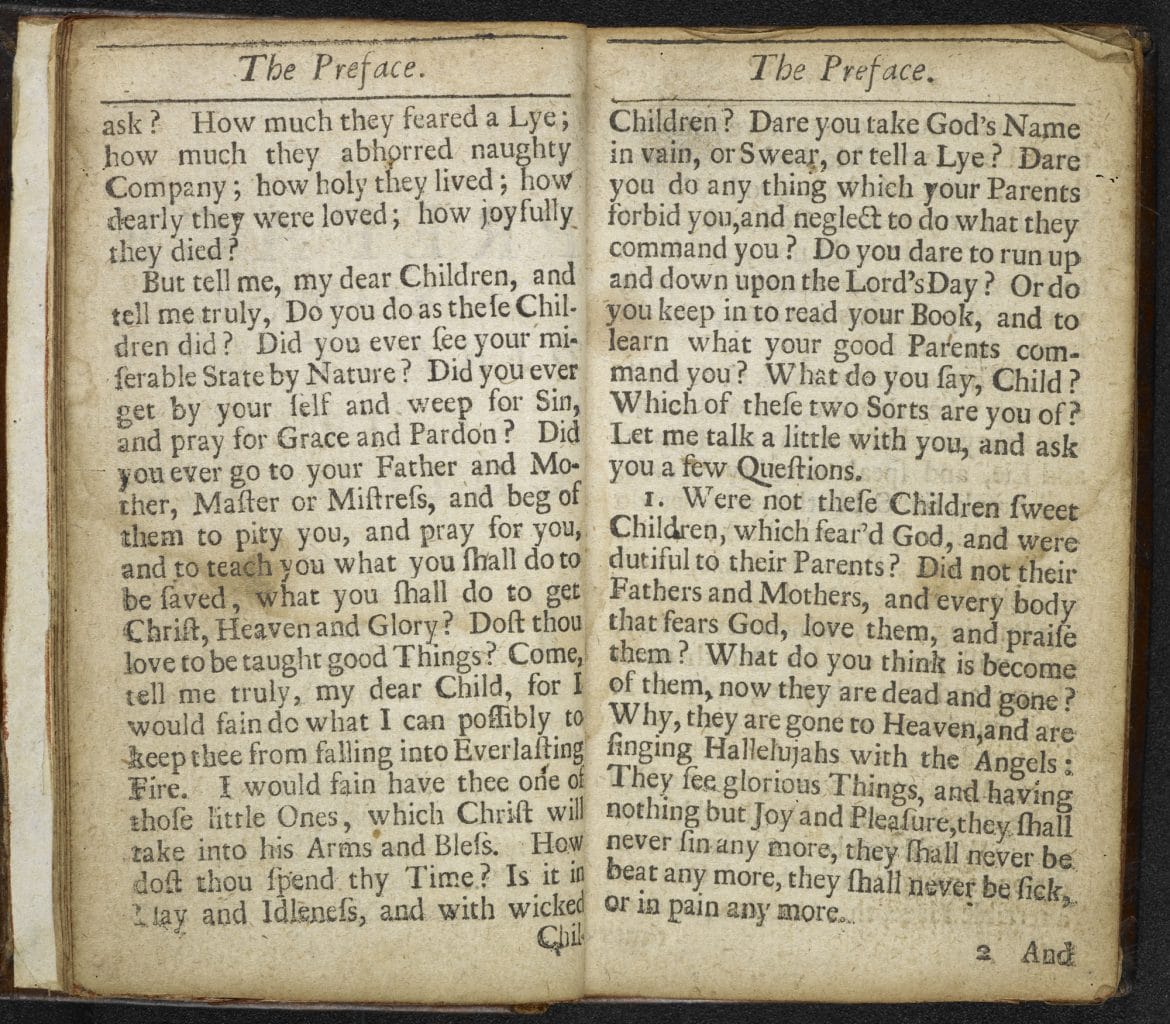

Moral and instructional books for children were aimed at a ‘polite’ middle class readership, and provided models for correct modes of behaviour. These books simplified the complexities of ethical, religious and social issues, condensing them into easy-to-understand instruction. Two popular examples are Isaac Watts’ Divine Songs (1715) and James Janeway’s A Token for Children (1671), published in several editions throughout the century.

Blake reacted against this genre of instructional children’s literature in the Songs of Innocence and Experience, taking a popular literary form and subverting it. ‘London’ in Songs of Experience, for instance, inverts the self-righteousness of the speaker in Watts’ ‘Song IV’ from his hugely popular Divine Songs (1715). Watts’s child, speaking in the first person, looks at the ‘Poor’, ‘Children … half naked’ and those who ‘early learn to swear, and curse, and lye, and steal’, and responds by promising to fear God, and love him ‘more than they’.

In contrast, Blake’s response to the abuse of children is the howl of outrage at the end of ‘London’:

But most thro’ midnight streets I hear

How the youthful Harlots curse

Blasts the new-born Infants tear

And blights with plagues the Marriage hearse

In James Janeway’s A Token for Children argument is perhaps more complex – his response to the horror of the Plague is that the security of salvation is preferable to the despair of life, and his dying children are acutely and demonstrably aware of heaven. Blake’s children are equally aware of heaven, and death is indeed present in the Songs, but fundamentally his view is that of a child rather than a preaching adult.

How does Blake’s omission of moral resolution affect the tone of the poems?

Blake’s general refusal to provide a moral resolution to the situations that arise in the Songs of Innocence and Experience shows him turning his back on the easy moral lessons of this kind of children’s literature, probably to the discomfort of many of his readers. Even a close friend, Benjamin Malkin, entirely missed the irony in ‘Holy Thursday’ in Innocence, reading the poem as an approval of the orphan children’s orchestrated thanksgivings.

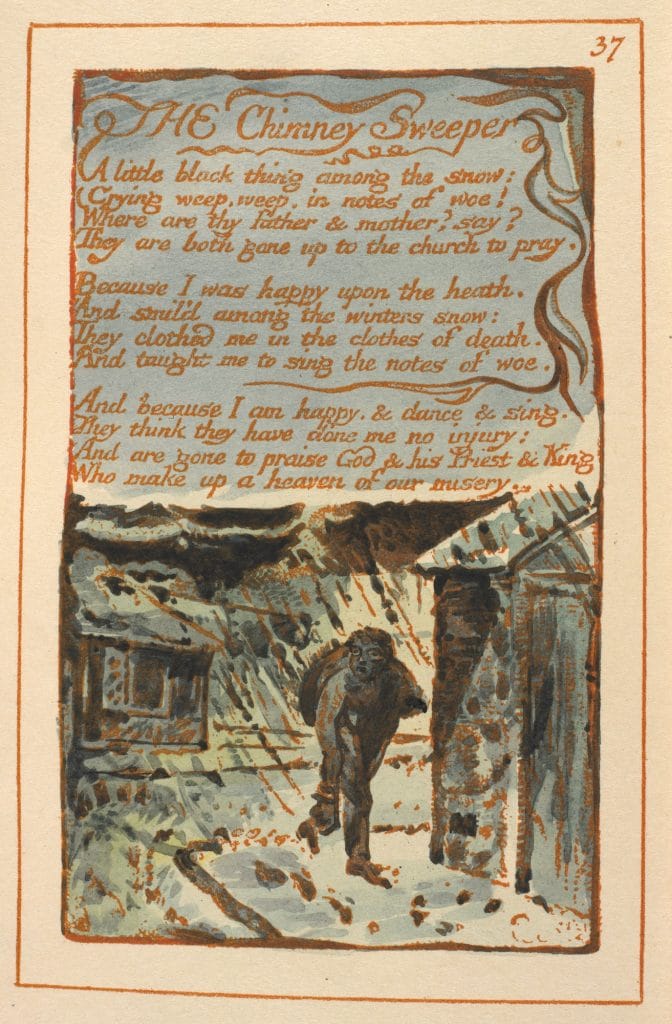

When a moral is provided, as in the case of ‘The Chimney Sweeper’, in Innocence, it is so trite as to be provocative:

So if all do their duty they need not fear harm

Sitting at the end of a poem that begins with a father selling his child into the chimney-sweeping trade, this challenges the reader, who is addressed directly as furthering this trade – ‘your chimneys I sweep’ – and is thus complicit in the abuse.

The use of ambiguity, irony and outrage within a context of what appeared to be poetry for children probably startled Blake’s readers. But then, while he claimed that children could ‘elucidate his visions’ as well as adults, he never said that the Songs were for children.

In Hymns for the Amusement of Children (1770) the poet Christopher Smart writes directly to children without taking any stance of judgement; his work and that of Sarah Trimmer propose a respect for the simple and for the natural world which are both seen in Blake.

What was the quality of book production for children?

While the tiny chapbooks maintained a tradition of robust and naïve woodcut illustration, towards the end of the century there was a rise in the sophistication of illustrations in children’s books; The Infant’s Library (1800) has engraved illustrations that were hand-coloured, like Blake’s songs, with considerable care and imagination. The layout and size of print was often clearly planned for the child-reader, as in Mrs Barbauld’s Hymns in Prose for Children (1787).

How are different theories of childhood reflected in the literature?

Through the period there were differing attitudes to the concept of childhood. Christian morality proposed the idea of ‘original sin’; children were inherently evil and had to be redeemed (often by punishment) and learning to be good Christians. In 1799 Hannah More wrote that it was ‘a fundamental error to consider children as innocent beings’. Chapbook stories that link piety to worldly success reflect these views, as do Watts’s Divine Songs and Janeway’s Tokens for Youth.

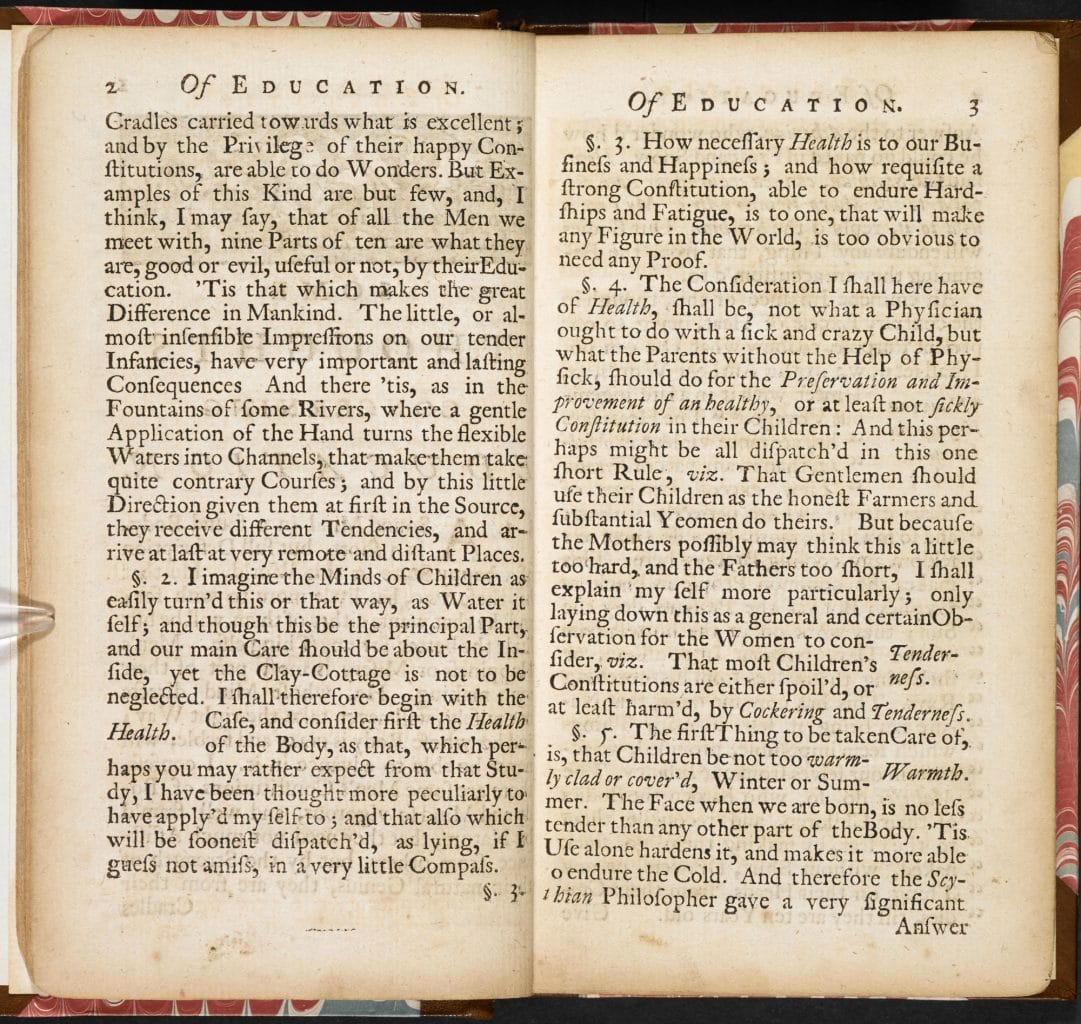

But John Locke’s Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693) proposed that the child’s mind was a blank canvas, open to any suggestions, and therefore child development should be carefully managed in order to create worthy and useful citizens. Though many children’s books showed that religious behaviour may be rewarded in heaven (Janeway) or by an advantageous marriage (The Renowned History of Goody-Two Shoes), intelligent, creative and non-violent education of the child, and by implication continuing self-improvement, was the duty of every individual.

Rousseau, however, denied both these views, claiming that children should be seen as distinct entities, innately moral and only degraded by exposure to adult behaviour. The idea of children as distinct from adults, and indeed having something to teach adults, is clearly reflected in many of Blake’s Songs.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Julian Walker

Julian Walker is an artist, writer and educator, who works with the Learning Department at the British Library. His research-based art and writing practice explores language, social history, the nature of objects and engagement with the past. He is co-author of Trench Talk: Words of the First World War (Stroud: Spellmount, 2012).