The Notebook of William Blake

出版日期: 1787–1818 文学时期: Romantic 类型: Romantic poetry 创建: 1787–1818

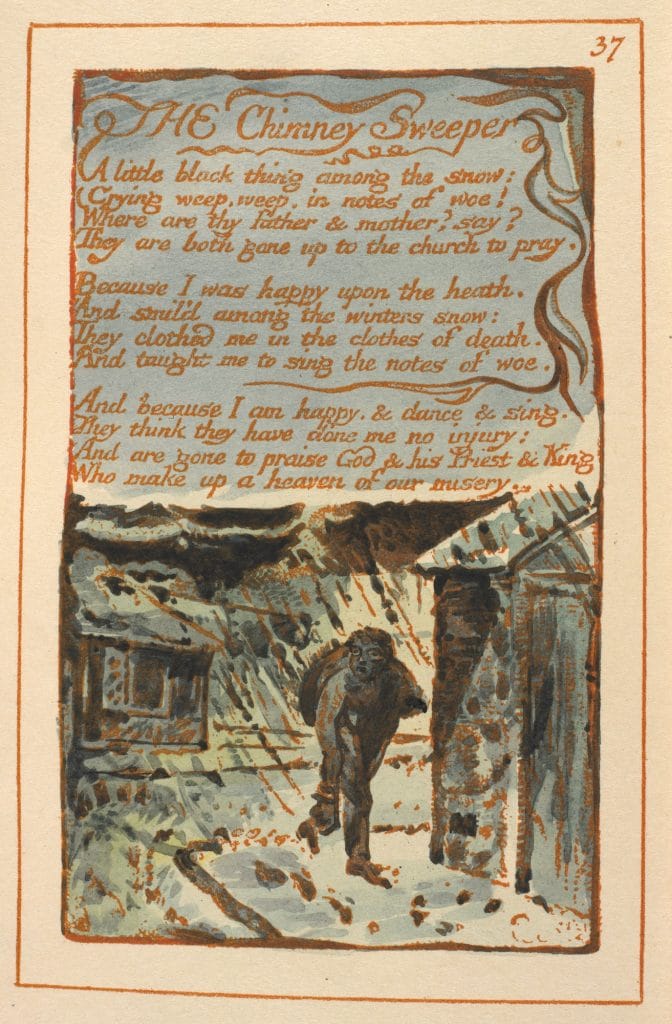

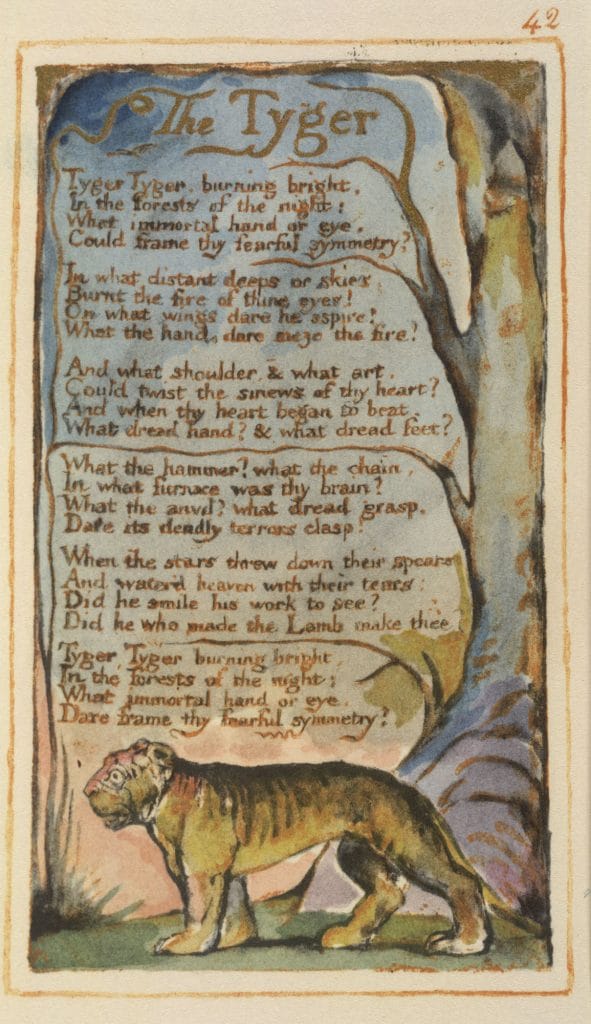

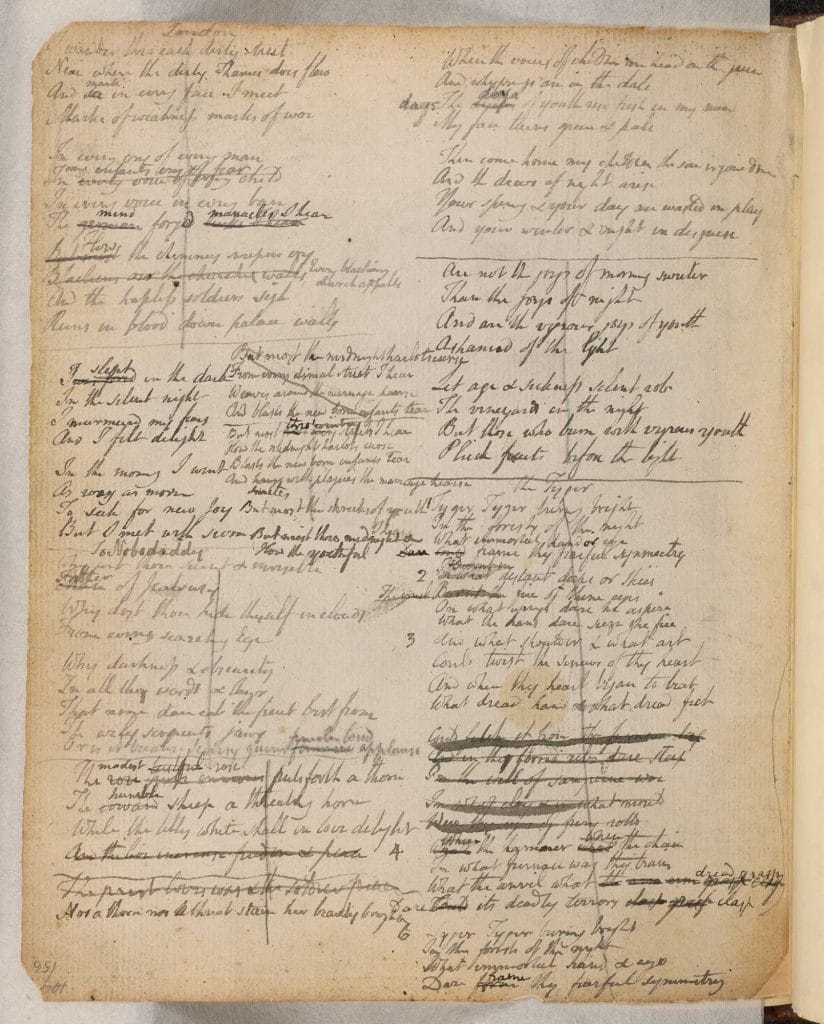

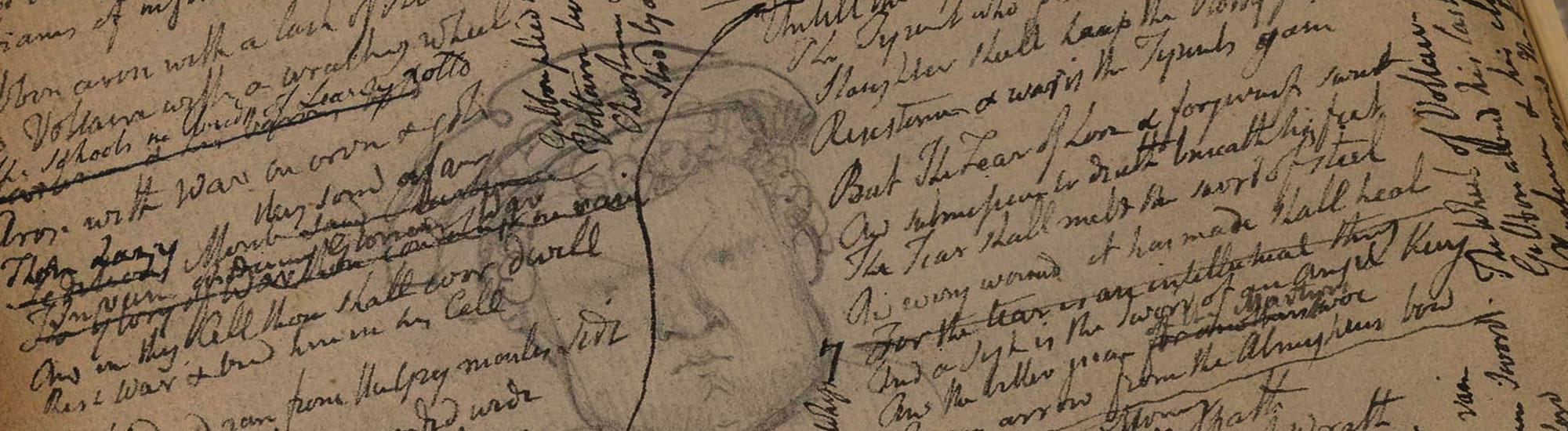

Created in the politically charged atmosphere of late 18th-century England, Blake’s poetry explores the tensions between human passions and social and political conventions. The poet tackles radical subjects such as poverty, child labour and the repressive nature of the Church, as well as the right of children to be treated as individuals with their own desires. Blake’s Notebook, which contains 30 years worth of sketches and drafts, offers a fascinating insight into the creative process behind some of his most famous poems, including ‘London’, ‘The Tyger’ and ‘The Chimney Sweeper’.

Who was William Blake?

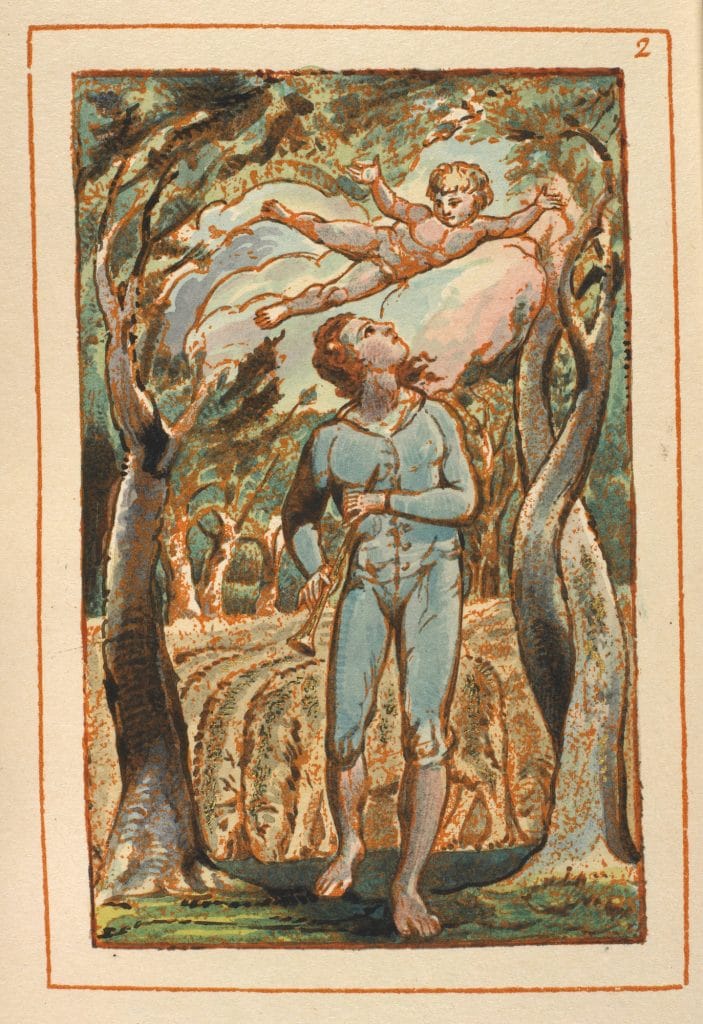

The third of six children of a Soho hosier, William Blake lived and worked in London all his life. As a boy, he claimed to have seen ‘bright angelic wings bespangling every bough like stars’ in a tree on Peckham Rye, one of the earliest of many visions. In 1772, he was apprenticed to the distinguished printmaker James Basire, who extended his intellectual and artistic education. Three years of drawing murals and monuments in London’s Westminster Abbey fed a fascination with history and medieval art.

In 1782, he married Catherine Boucher, the steadfast companion and manager of his affairs for the whole of his chequered, childless life.

Although always in demand as an artist, Blake’s intensely felt visions and spiritual beliefs led to wild mental highs and lows, and later in life he was sidelined as being close to insanity. On his deathbed, he saw one last glorious vision, and ‘burst out in Singing of the things he Saw in Heaven’.

Blake’s printing process

Following his father’s death in 1784, Blake – in partnership with Catherine and with a former fellow apprentice to Basire, James Parker – established a print shop. He purchased a wooden rolling press for 40 pounds which allowed him to experiment with different printing techniques. It is probable that he was assisted by his beloved younger brother, Robert, an artist and student at the Royal Academy who may have lodged with the Blakes. When Robert fell ill with consumption (tuberculosis) in late 1786, it was Blake who almost single-handedly took care of him. Robert’s death in February 1787 greatly affected Blake, who subsequently retired to bed and later claimed to have fallen into an unbroken sleep for three days and nights.

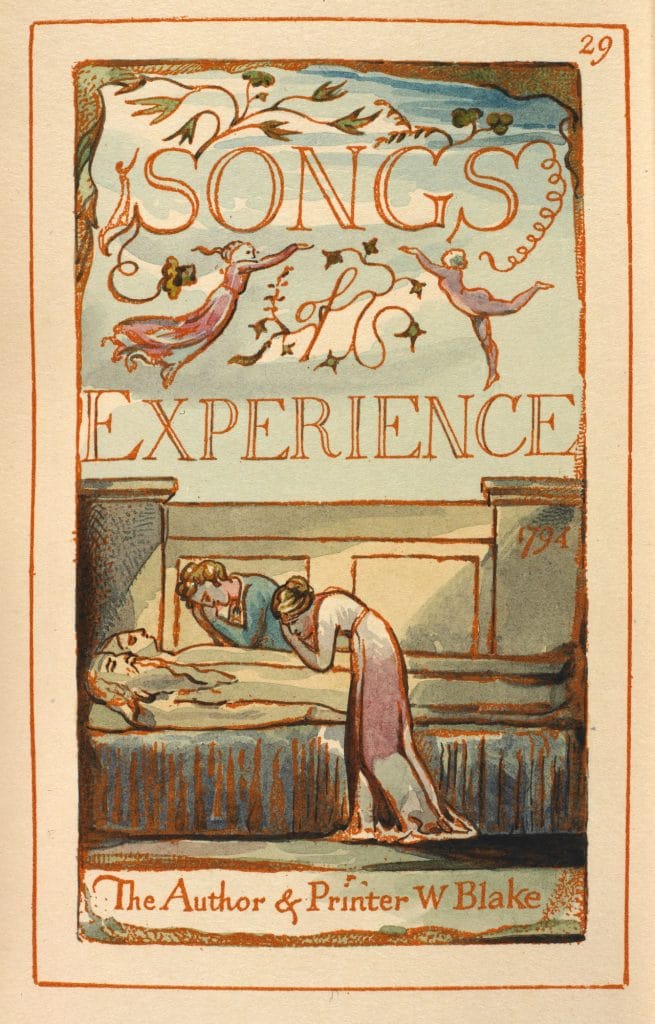

Robert’s presence stayed with Blake, who claimed that the inspiration for a novel method of engraving was revealed to him by his brother in a vision, a year after his death. Blake subsequently developed a technique known as ‘relief etching’. This allowed him to write his text directly onto a copper plate, at the same time as adding the accompanying design or illustration. He wrote on the plate (in reverse) in acid-resistant liquid, so that when this was then covered in acid, the acid etched away the uncovered areas of the plate. This left the text and design in relief, ready to be inked and then placed on his rolling press. In practical terms, this process removed the need to send his work out to costly printers. More significantly, the method allowed Blake to compose text and images at the same time from the same plate, a symbolic union of his twin creative forces. Blake himself praised ‘a method of printing which combines the painter and the Poet’ as ‘a phenomenon worthy of public attention’. The first of what he later called his ‘illuminated books’ appeared in 1788.

Michael Phillips demonstrates William Blake’s printing process, explaining how it relates to his work as a poet and artist. Filmed at Morley College, London.

More information about William Blake’s printing process is available on Michael Phillips’s website: http://www.williamblakeprints.co.uk

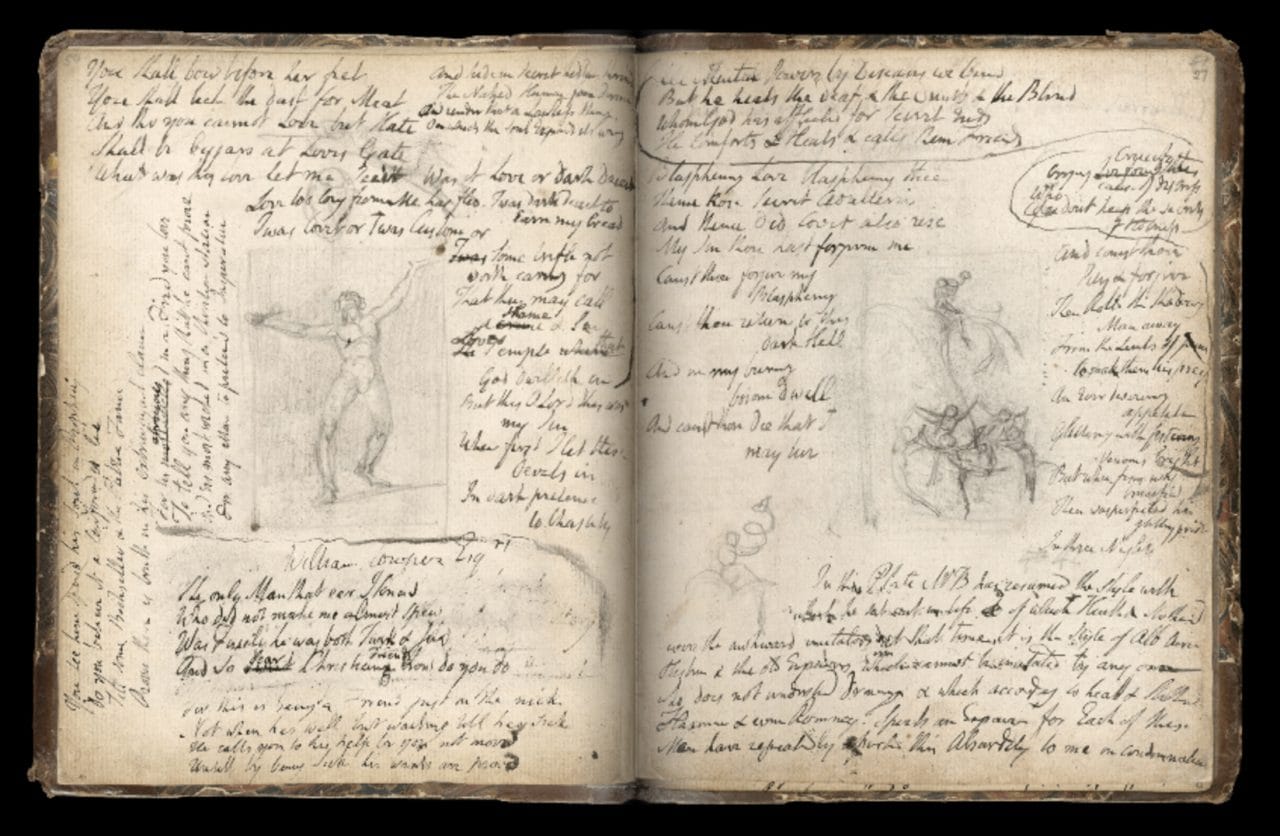

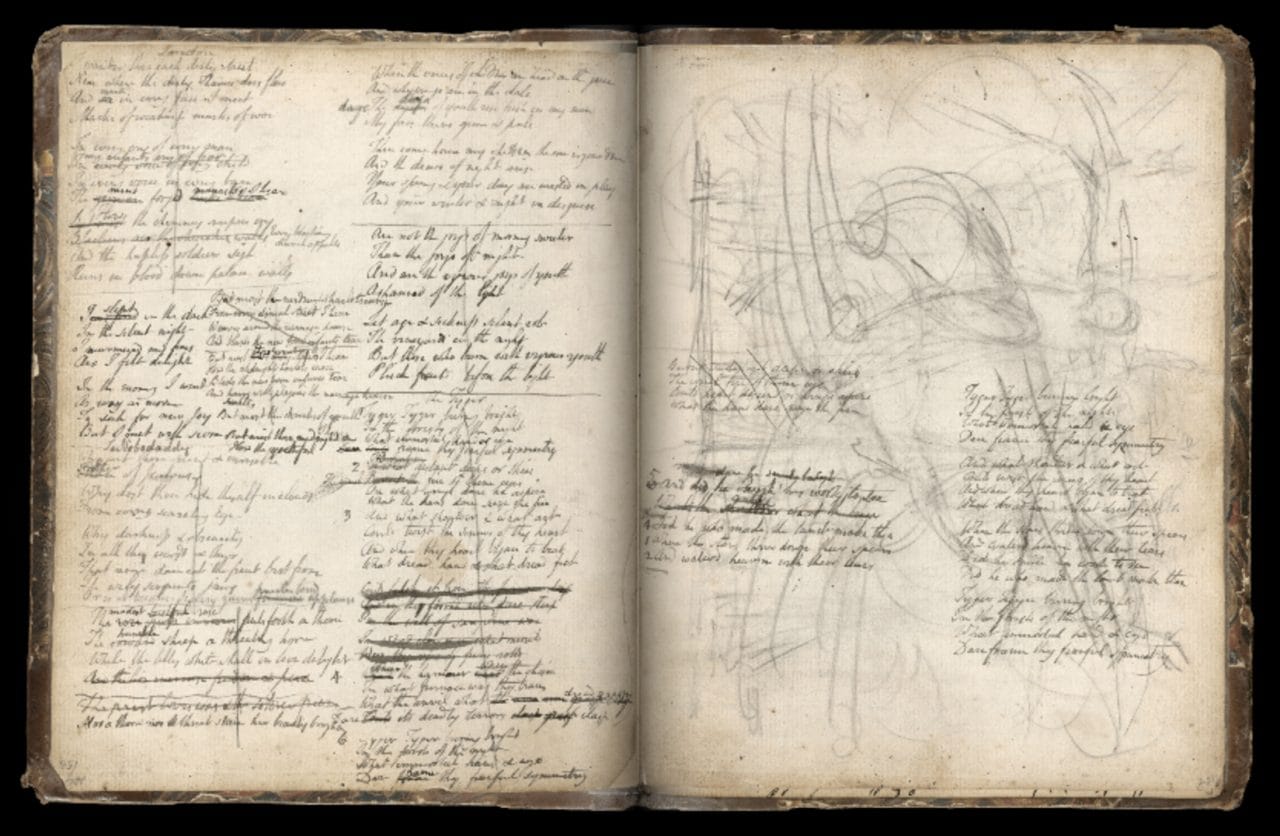

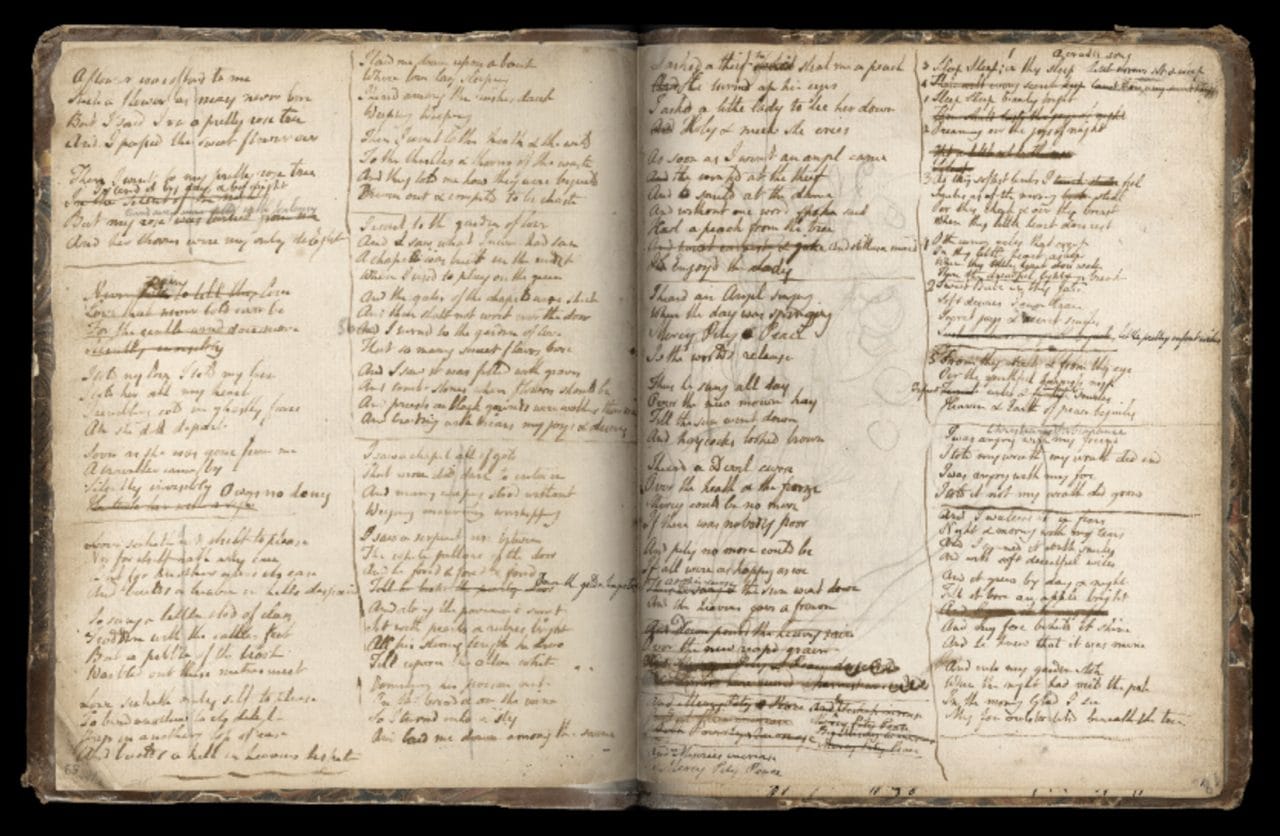

The Notebook

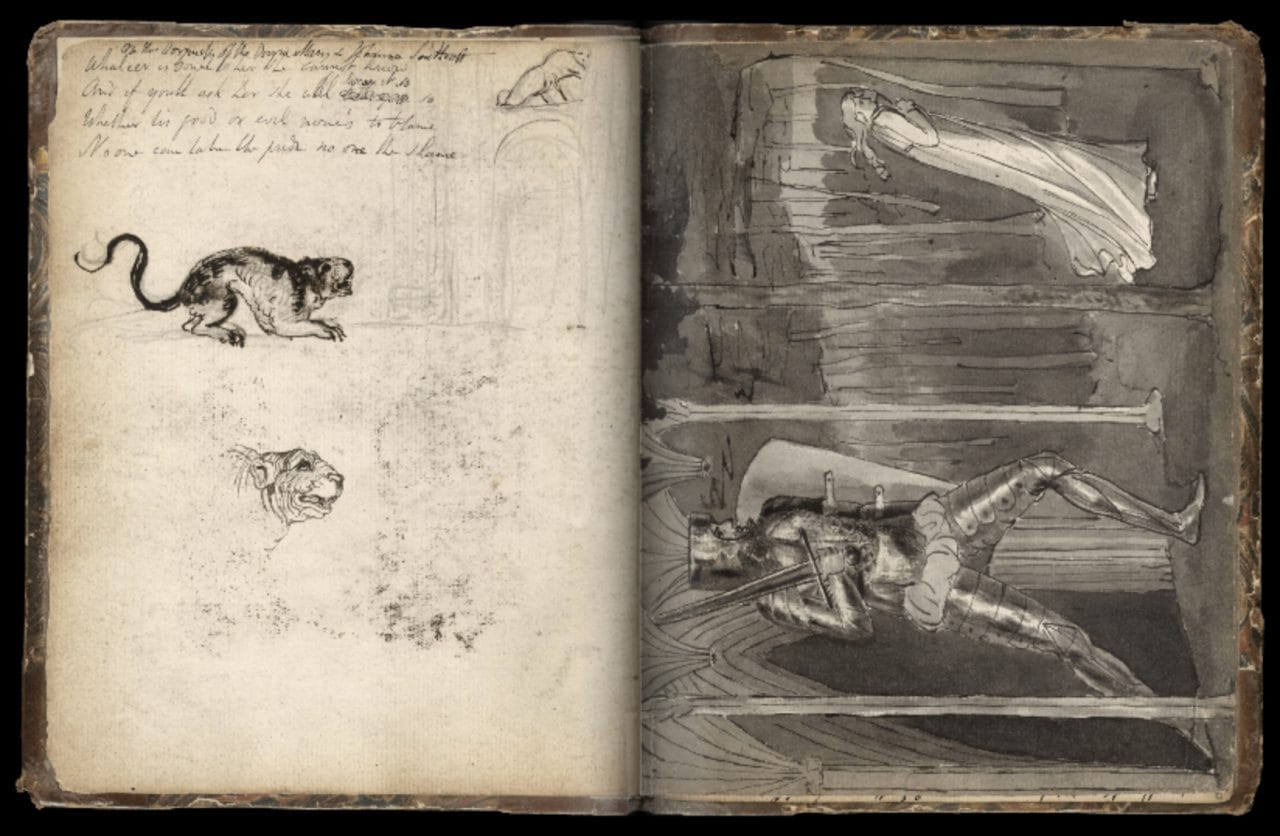

This small notebook (159 x 197 mm; 58 leaves) belonged to Blake’s brother, Robert. The notebook contained a few of Robert’s drawings when it passed to his brother upon his death, and Blake was to treasure it as a reminder of Robert throughout his life. It was also, however, a practical work book that Blake filled with sketches and drafts of poems, and which now provides an enthralling insight into the composition of some of Blake’s most well-known and highly regarded works.

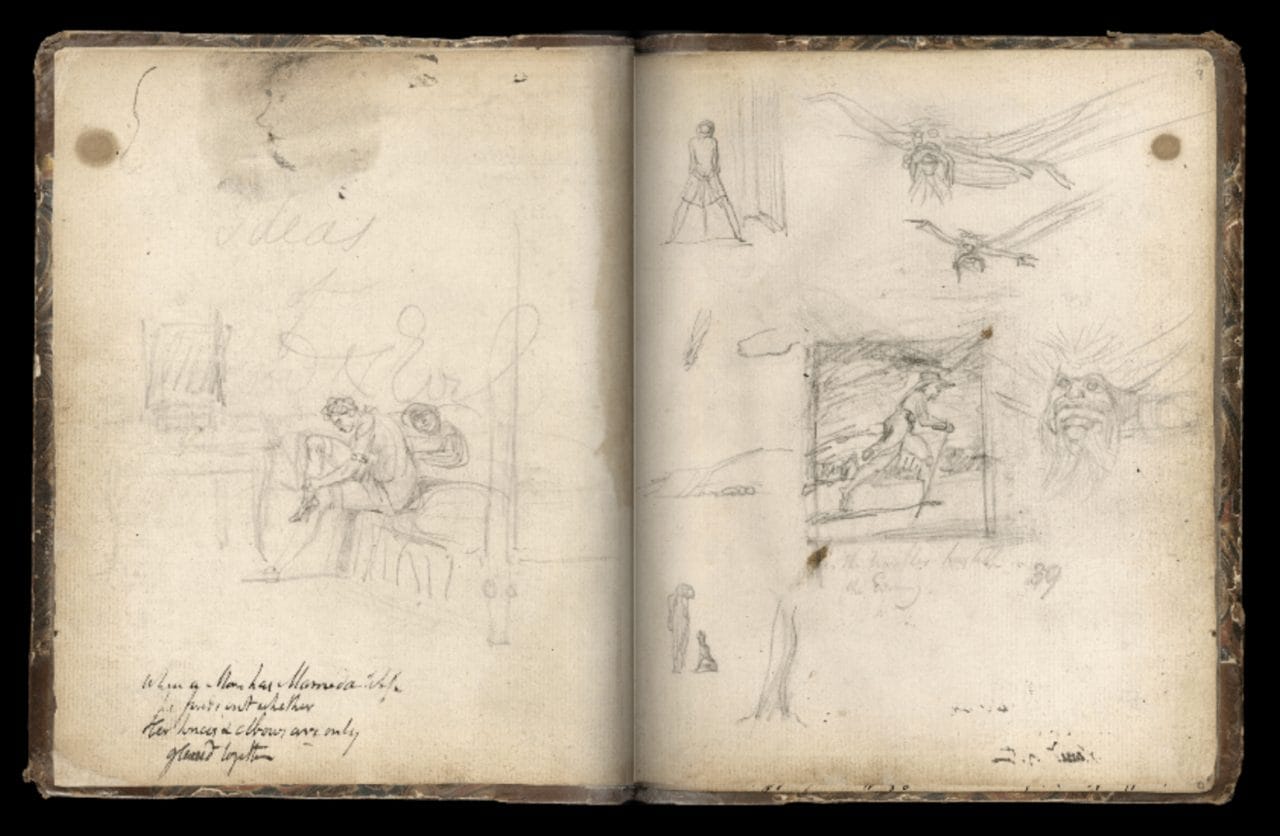

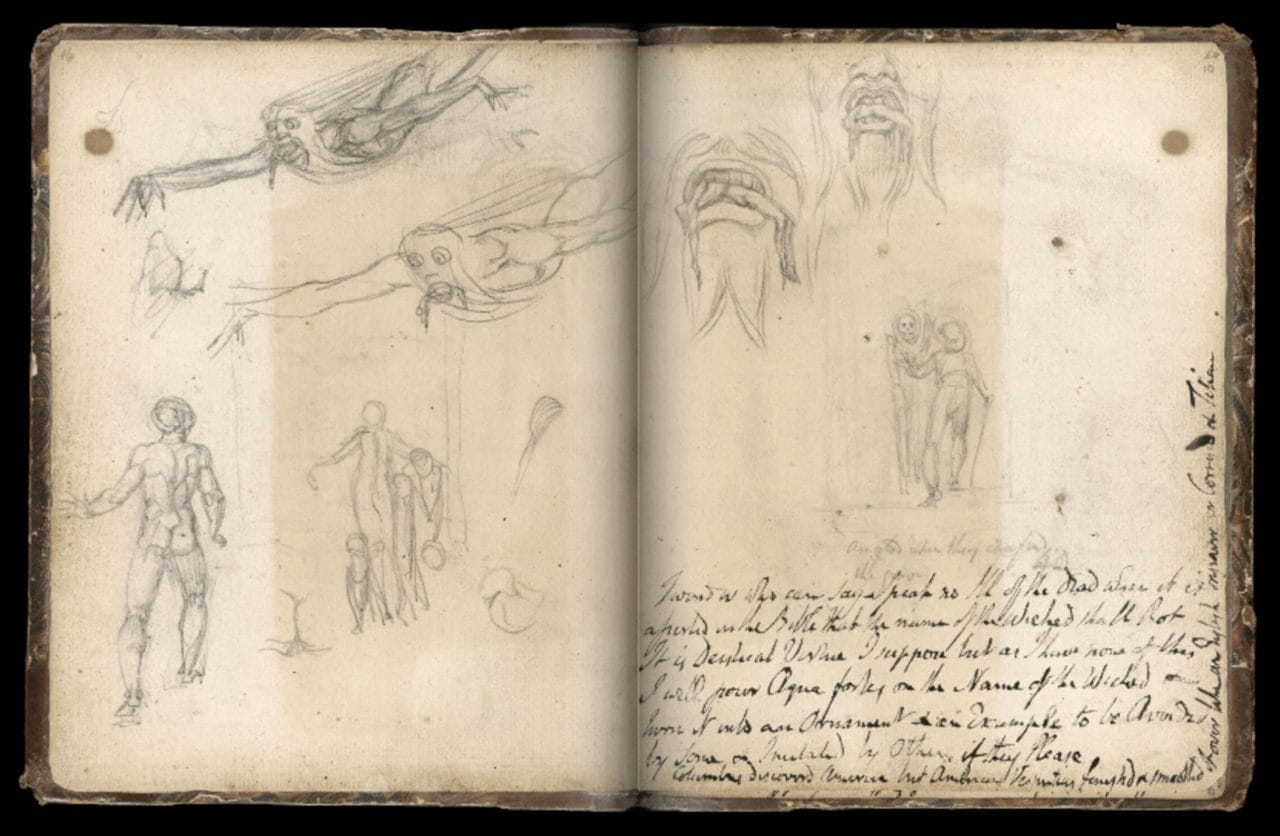

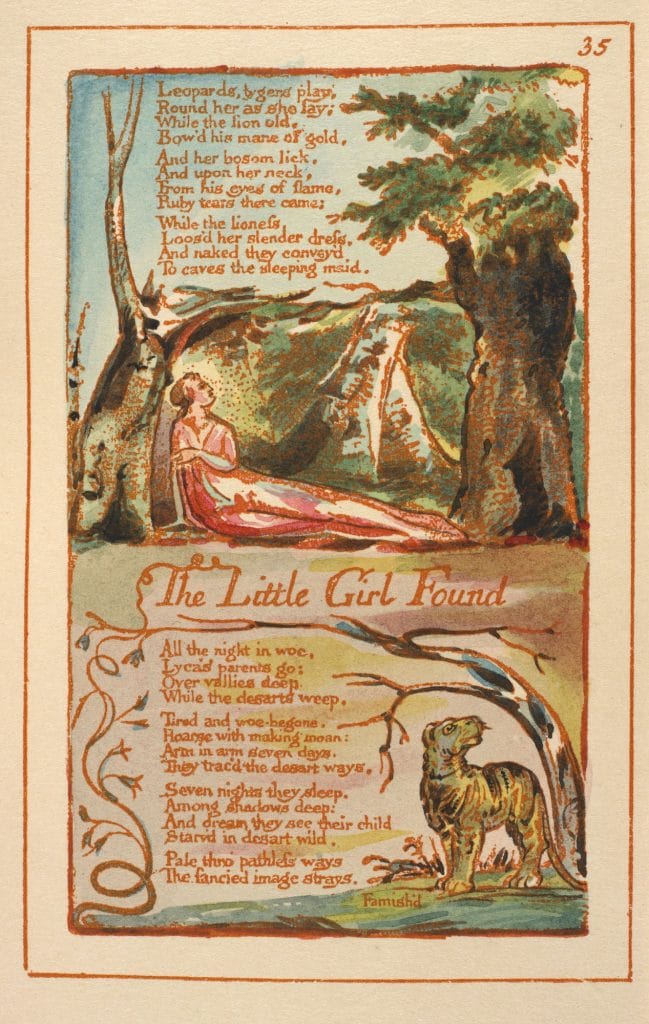

Blake used the notebook for over 30 years, starting from the front and drawing a series of emblems in pencil under the title ‘Ideas of Good and Evil’. These emblems record the journey of man from birth to death and may well have been prompted by Blake’s reaction to his brother’s premature death. From this group of emblems, Blake selected 17 designs which he etched and published in a small volume entitled For Children: The Gates of Paradise (1793). When Blake reached the end of the notebook, probably in about 1793, he turned it upside down and began working from the end on the back of each leaf. He used these pages to transcribe fair copies (later heavily annotated) of earlier drafts of poems, many of which would appear in Songs of Experience (1794).

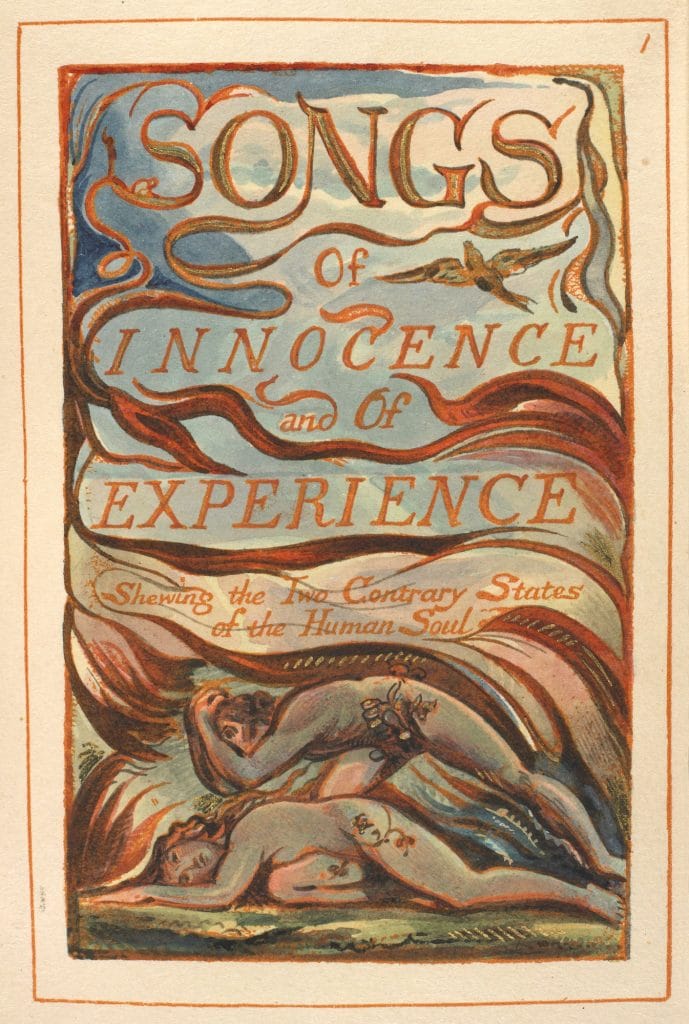

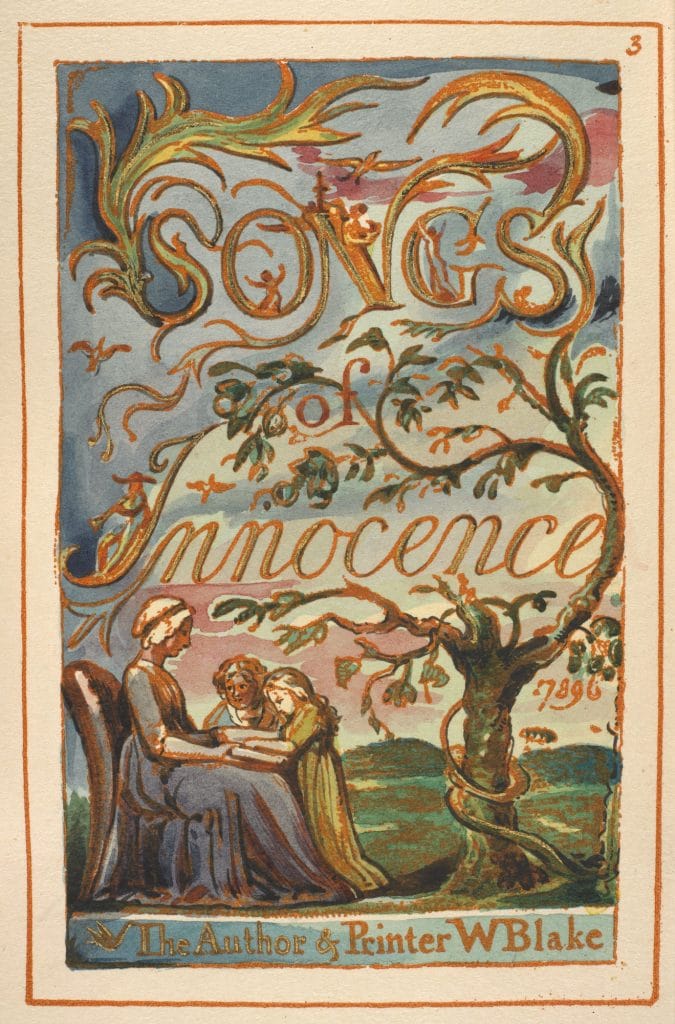

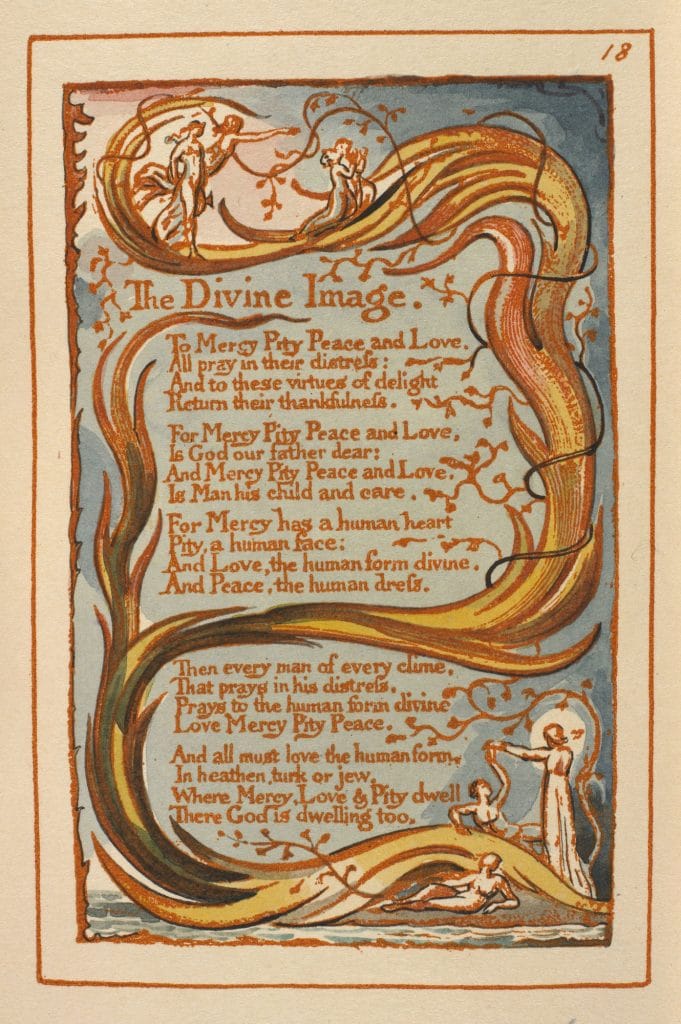

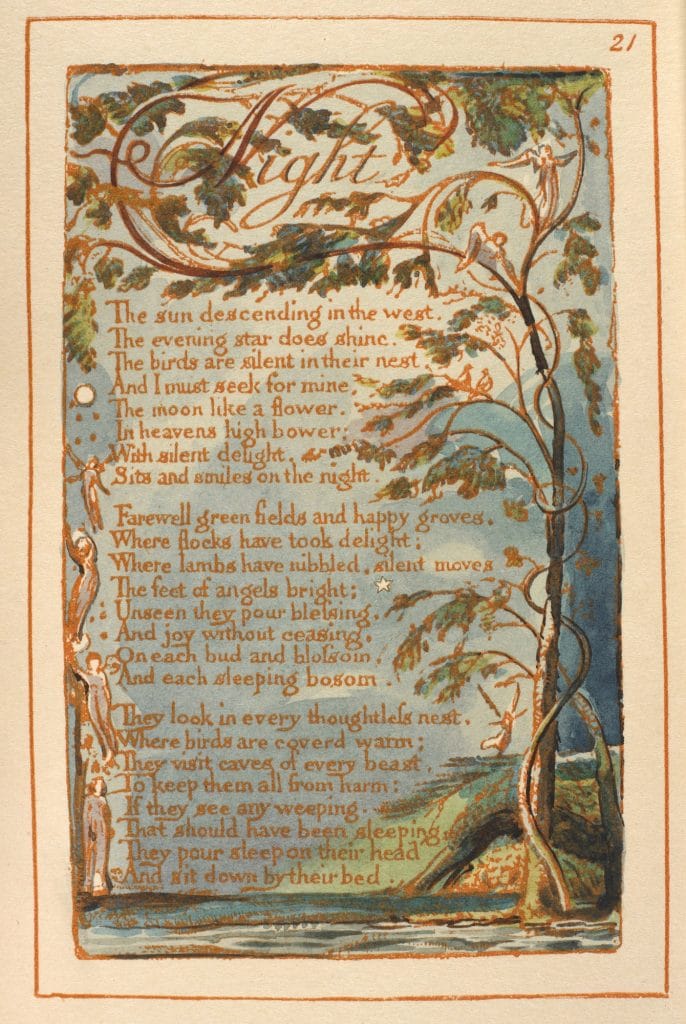

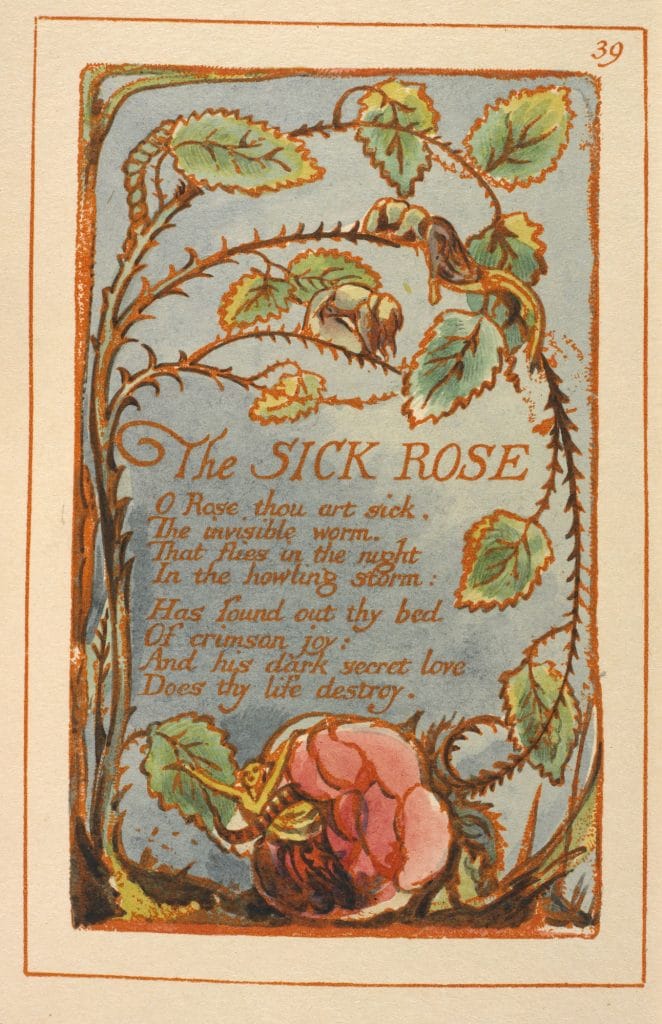

Songs of Innocence and Experience

Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience is perhaps his most famous collection of poems. In this collection he investigates, as he put it in the subtitle, ‘the two contrary states of the human soul’. Despite the simple rhythms and rhyming patterns and the images of children, animals and flowers, the Songs are often troubling, argumentative or satirical, and reflect Blake’s deeply held political beliefs and spiritual experience.

Though Blake stated that children could understand his work as well as, or better than, adults, this is rather a comment on how children understand things directly and without the clouded perceptions that derive from the compromises required by adult life. But the songs are specifically ‘of’ and not ‘for’ innocence and experience. The work echoes the rhythms and forms of popular 18th-century children’s poetry and ballads. However, while much of the verse directed at middle-class children at this time contained simple didactic messages, Blake deliberately avoids this type of dogmatic morality – instead many of the poems in Songs of Innocence and Experience contain unsettling ambiguities.

Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience is perhaps his most famous collection of poems. In this collection he investigates, as he put it in the subtitle, ‘the two contrary states of the human soul’. Despite the simple rhythms and rhyming patterns and the images of children, animals and flowers, the Songs are often troubling, argumentative or satirical, and reflect Blake’s deeply held political beliefs and spiritual experience.

Though Blake stated that children could understand his work as well as, or better than, adults, this is rather a comment on how children understand things directly and without the clouded perceptions that derive from the compromises required by adult life. But the songs are specifically ‘of’ and not ‘for’ innocence and experience. The work echoes the rhythms and forms of popular 18th-century children’s poetry and ballads. However, while much of the verse directed at middle-class children at this time contained simple didactic messages, Blake deliberately avoids this type of dogmatic morality – instead many of the poems in Songs of Innocence and Experience contain unsettling ambiguities.

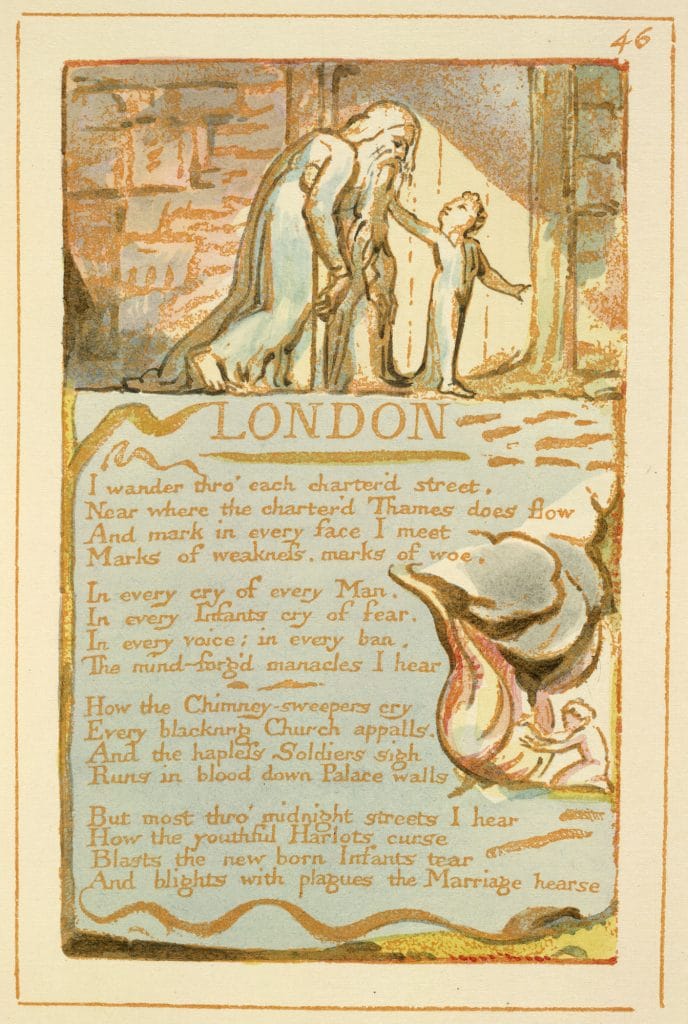

London

William Blake composed his poem ‘London’ in the summer of 1792. We can see his draft of the poem in his Notebook above, and the engraved version printed in his Songs of Experience.

In this poem, Blake explores poverty, revolution and the power of the imagination. His depiction of the ‘dirty’ streets of London reflects his view of the fallen state of contemporary society. He sees a city in a state of moral and physical degeneration, epitomised by the suffering of the chimney sweeps, soldiers and prostitutes who populate the poem. However, Blake’s illustration in Songs of Experience suggests all hope is not lost: a young child gestures towards an open door through which we can perceive a beam of light. An old man looks trustingly down at him. The image suggests the possibility of redemption: a marriage of age and youth, reason and imagination.

‘London’ read by Stephen Critchlow. Courtesy of Naxos Audiobooks.

I wander thro’ each charter’d street,

Near where the charter’d Thames does flow.

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.

In every cry of every Man,

In every Infant’s cry of fear,

In every voice: in every ban,

The mind-forg’d manacles I hear

How the Chimney-sweeper’s cry

Every black’ning Church appalls,

And the hapless Soldier’s sigh

Runs in blood down Palace walls

But most thro’ midnight streets I hear

How the youthful Harlot’s curse

Blasts the new-born Infant’s tear

And blights with plagues the Marriage hearse.