Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’

出版日期: 1798 文学时期: Romantic 类型: Romantic

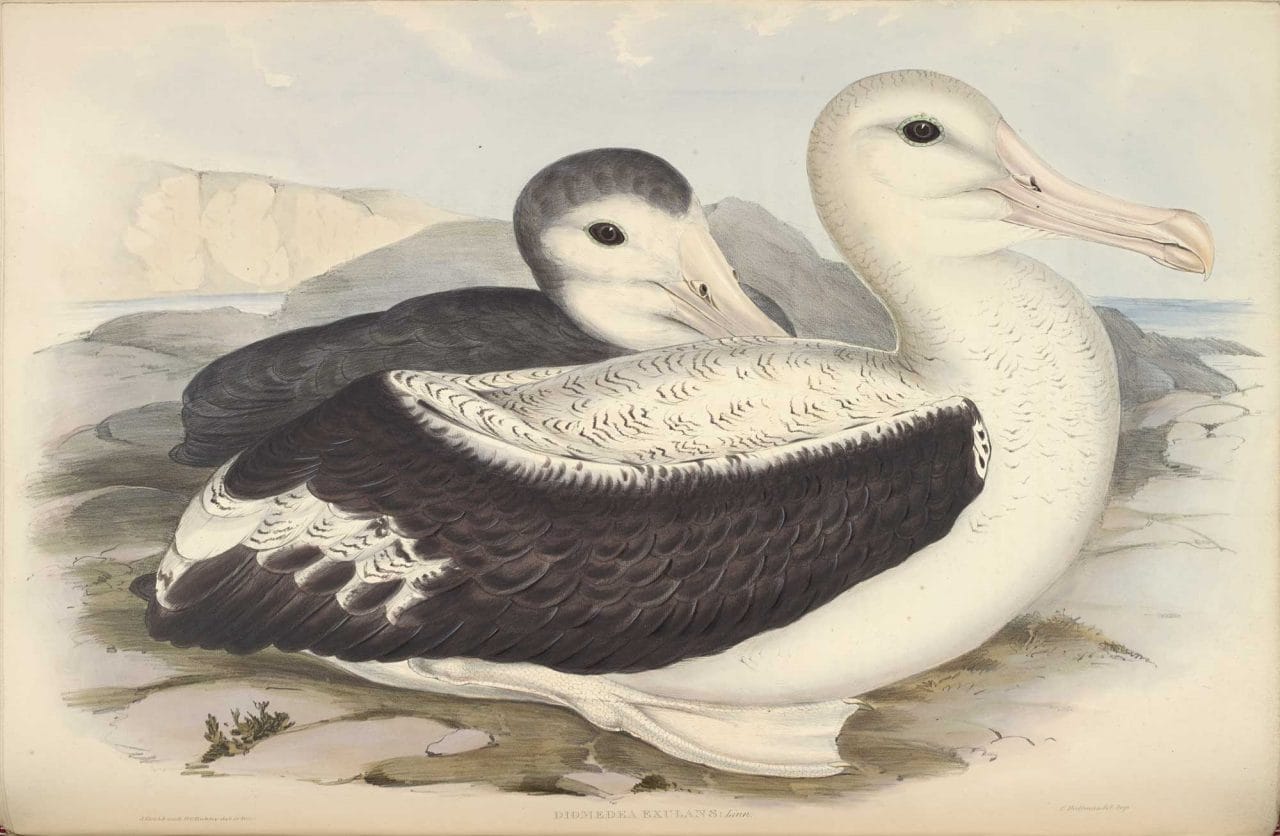

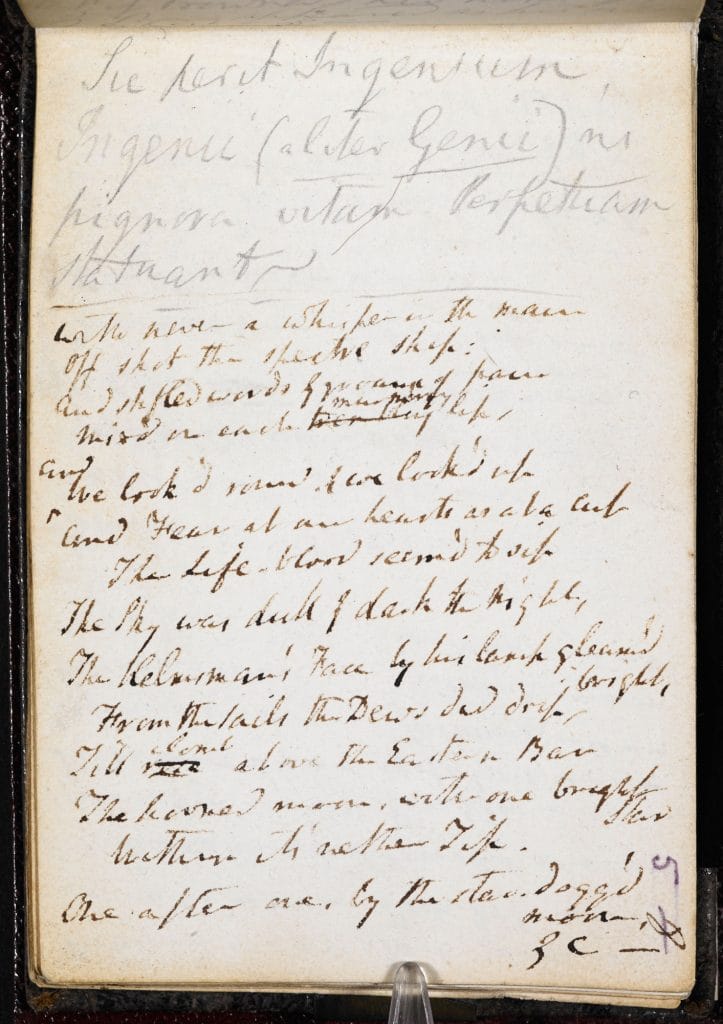

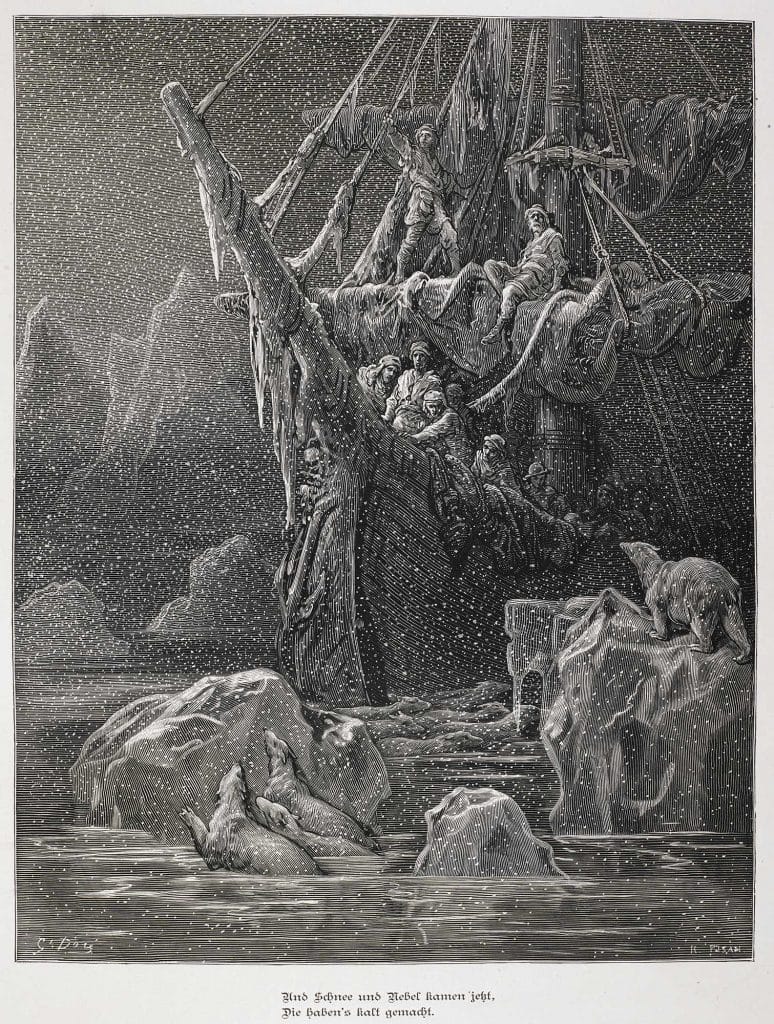

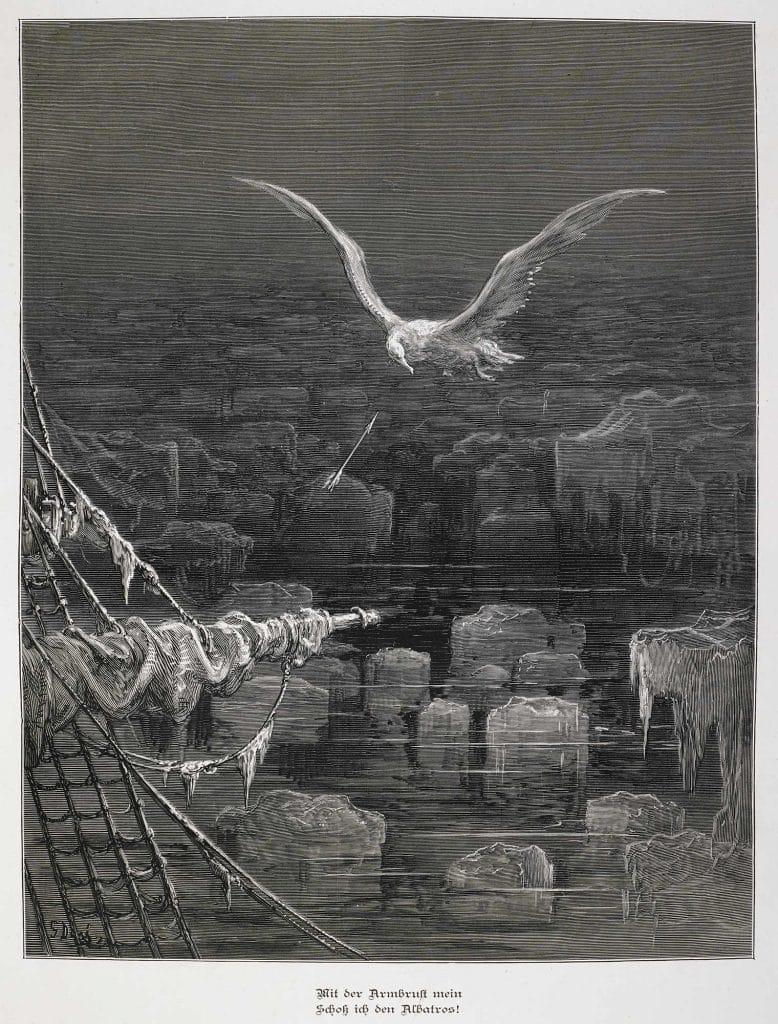

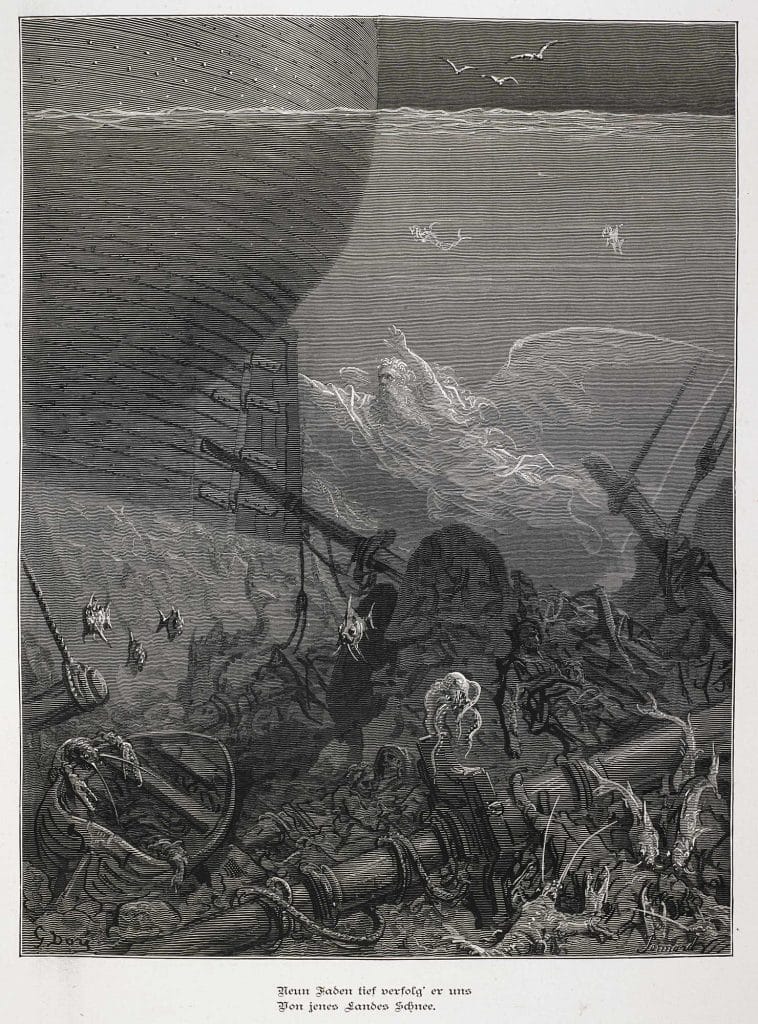

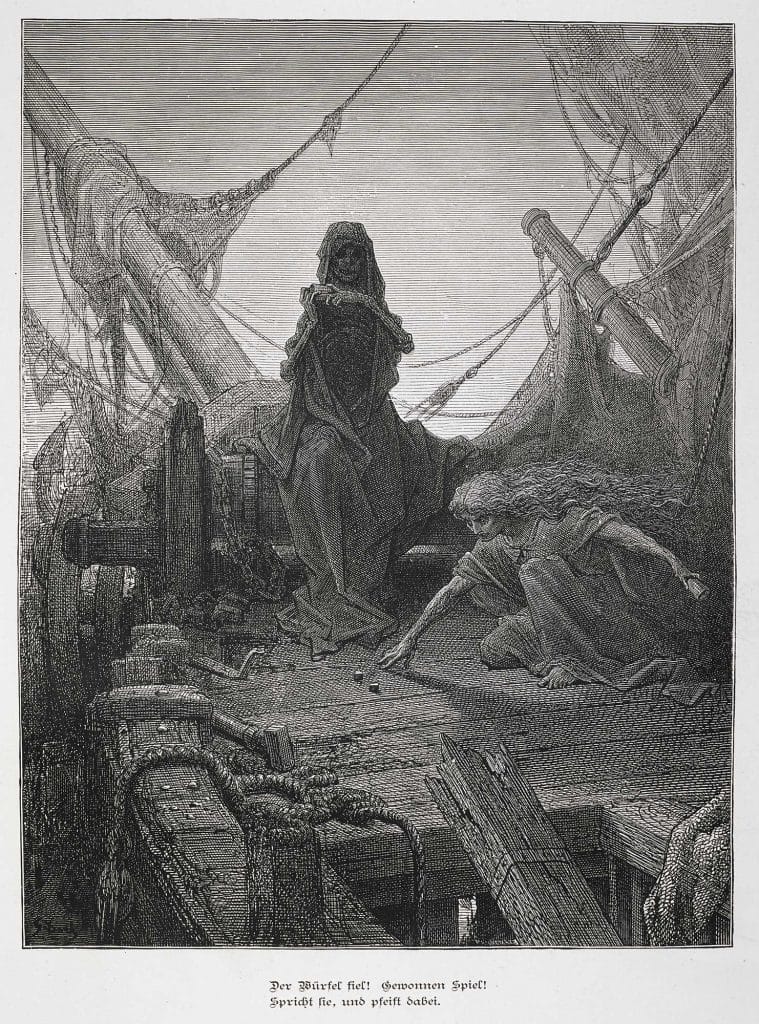

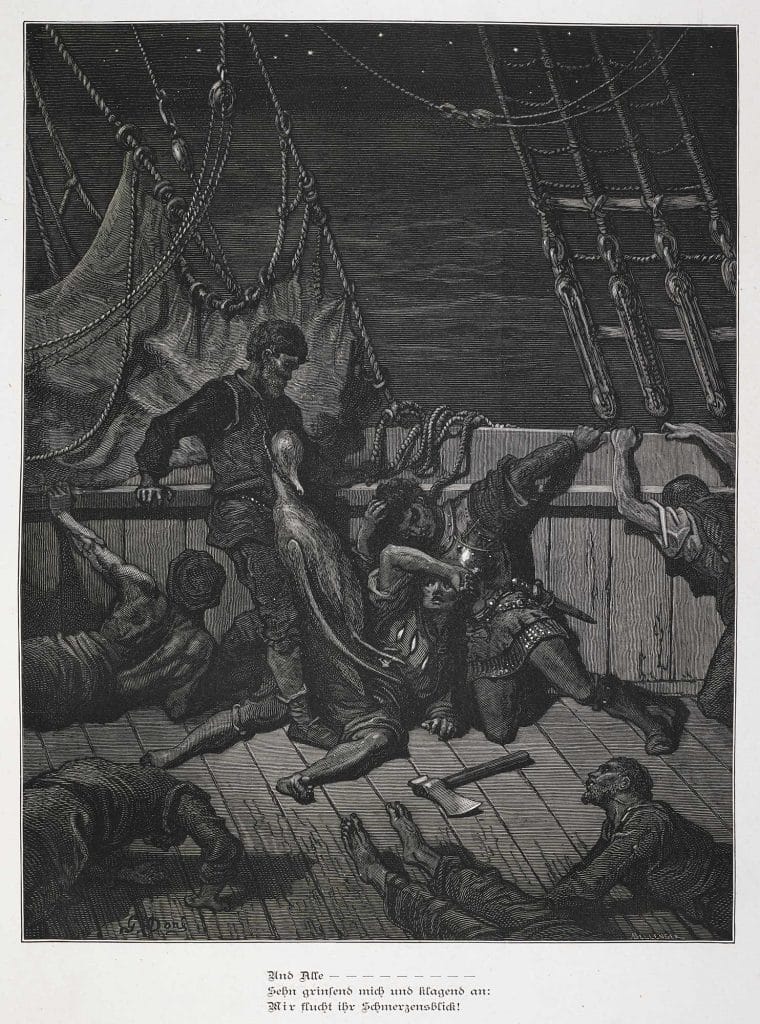

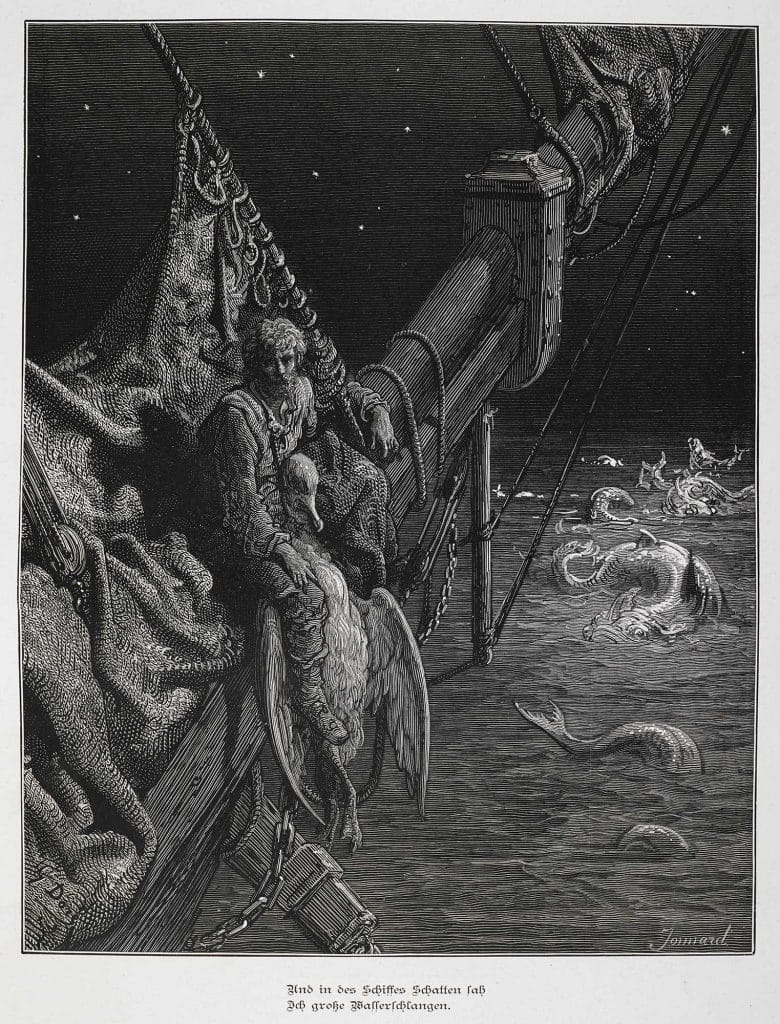

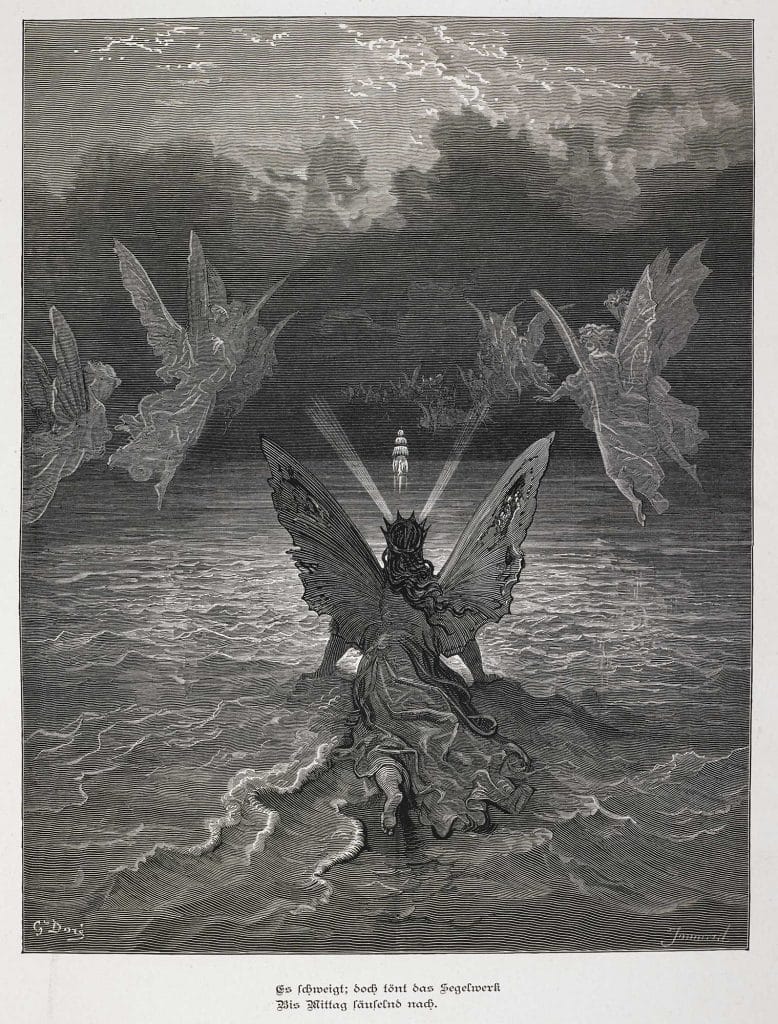

Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s (1772-1834) experimental, supernatural poem was originally published in Lyrical Ballads (1798), a collection of poems on which he collaborated with William Wordsworth. The mariner describes his ship becoming trapped in ice at the South Pole. After escaping, the sailors credit their salvation to an albatross; however, the mariner shoots the bird with a crossbow, and misfortunes follow. He is blamed by his shipmates, who hang the bird’s carcass round his neck. Gradually, the penitent mariner becomes more appreciative of the natural world, and this redeems him. Nevertheless, he continues to share his harrowing story. Critics have considered many allegorical meanings, but the poem defies reduction to a single interpretation.

The origins of ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’

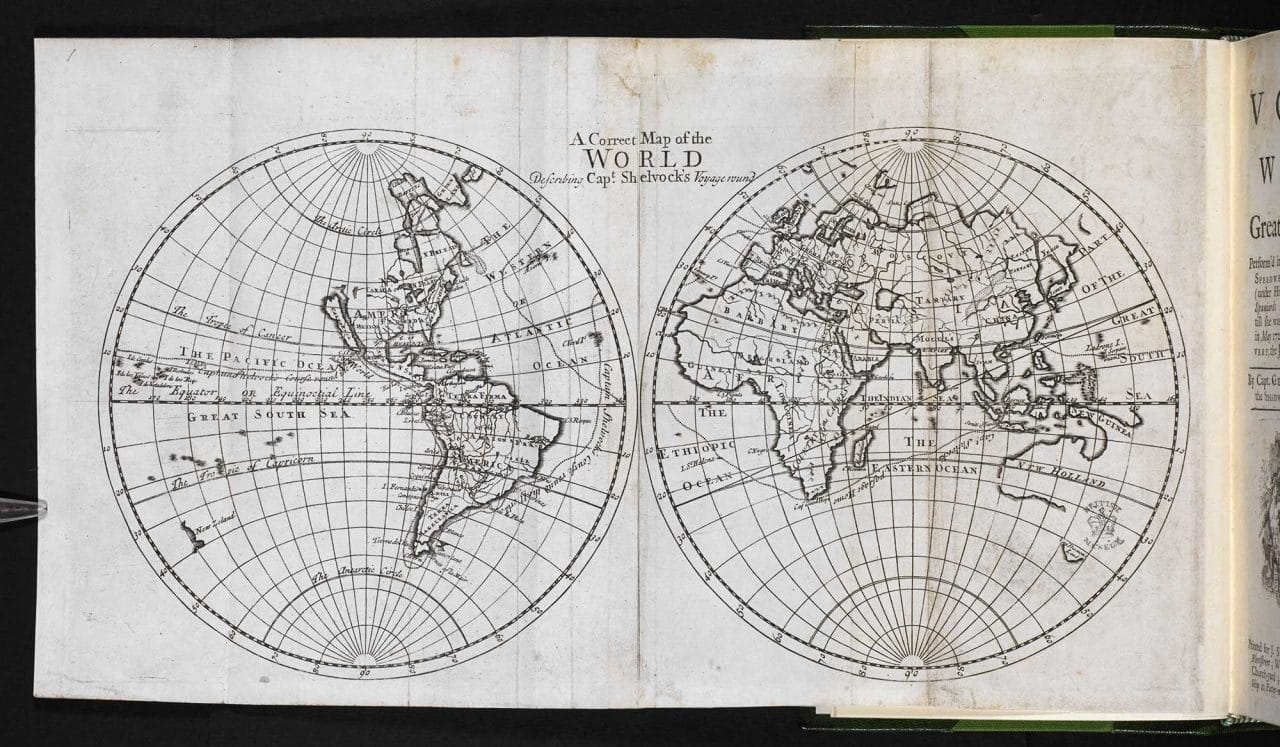

The episode that lies at the heart of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ – the killing of an albatross – was suggested by William Wordsworth, who had recently read George Shelvocke’s biographical Voyage Round the World by way of the Great South Sea (1726). On 1 October 1719, during a semi-authorised pirate expedition aboard the Speedwell in the South Seas, a black albatross that was following the ship was shot by Simon Hatley, the melancholy second captain. There are many species of albatross with dark plumage, so this was not a rare variety. The appearance of the bird is associated with bad weather in the mind of Simon Hatley, but for Shelvocke and the rest of the crew the bird was ‘a companion, which would have somewhat diverted our thoughts from the reflection of being in such a remote part of the world’.

The area to the south of Tierra del Fuego, off the southernmost tip of South America, was clearly cold and hostile; indeed the weather was so bitter that one of the seamen lost sensation in his hands and fell to his death. Coleridge sets his albatross incident much closer to the equator.

Coleridge’s poem also contains elements of the biblical Cain, the legend of the Wandering Jew, a man cursed to walk the rest of his life as penance (a ballad version is in Thomas Percy’s Reliques) and the Flying Dutchman, a legendary ghost ship doomed to sail the seas for ever following some unspecified crime.

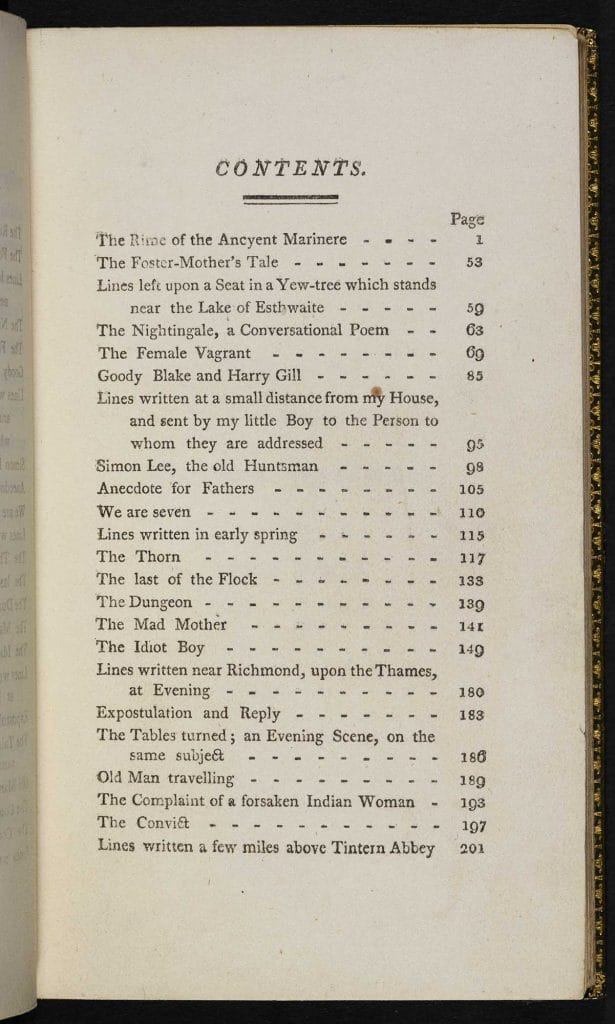

Lyrical Ballads

‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ was first published in Lyrical Ballads (1798), a collaborative venture with Wordsworth. The first proposal for this publication was for a two-volume work. The first would comprise two plays: Wordsworth’s The Borderers and Coleridge’s Osorio. But this plan was changed so that the book was anonymous and would begin with the poem ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’. In the preface Wordsworth describes the poem as ‘professedly written in imitation of the style, as well as the spirit of the elder poets’. The poem is introduced as ‘The Rime of the Ancyent Marinere’, in seven parts.

The poem was so different from all the other works in the collection that readers had difficulty understanding it. Coleridge used archaic spellings and obsolete words, and an often inverted word order, apparently driven by the need to achieve rhymes:

The Marineres all ‘gan pull the ropes,

But look at me they n’old;

Thought I, I am as thin as air –

They cannot me behold.

The first reviews found the style and content bewildering, ‘more of the extravagance of a mad German poet, than of the simplicity of our ancient ballad writers’, wrote a reviewer in the Analytical Review in December 1798. An interest in old English ballads or songs had recently been revived, and the poem seemed deliberately confusing. The English poet Robert Southey famously wrote, ‘we do not sufficiently understand the story to analyse it’ (Critical Review, October 1798).

The following year Wordsworth wrote to the publisher to say that he felt the inclusion of ‘The Rime of the Ancyent Marinere’ had been harmful to the Lyrical Ballads, and proposed omitting it from the second edition.

For the second edition it was moved from the opening position to the penultimate position of the first volume.

‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ lines 1–28, read by Michael Sheen. Courtesy of Naxos Audiobooks.

Revising the ‘Ancient Mariner’

‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ is the only poem on which Coleridge continued to work – and unarguably improve – until shortly before his death. Faced with the widespread criticism of the poem’s archaic language and general inaccessibility, Coleridge modernised around 40 spellings and terms, deleted 46 lines and added seven new ones. Parts v and vi were the most substantially altered, with careful revisions made to the section from ‘And soon I heard a roaring wind’ to ‘The dead men gave a groan’ (ll. 309-30, 1817 text).

Dreams and imagination

Coleridge was as much a prose and theoretical writer as he was a poet, as revealed in his major autobiographical work, Biographia Literaria, published in 1817.

In one of the most famous passages in Biographia Literaria, Coleridge offers a theory of creativity (pp. 95–96). He divides imagination into primary and secondary spheres. Primary imagination is common to all humans: it enables us to perceive and make sense of the world. It is a creative function and thereby repeats the divine act of creation. The secondary imagination enables individuals to transcend the primary imagination – not merely to perceive connections but to make them. It is the creative impulse that enables poetry and other art.

Biographia Literaria contains the first instance of the phrase ‘suspension of disbelief’. Writing about his contributions to the Lyrical Ballads, Coleridge says that although his characters were ‘supernatural, or at least romantic’, he tried to give them a ‘human interest and a semblance of disbelief’ that would prompt readers to the ‘willing suspension of disbelief … which constitutes poetic faith’.

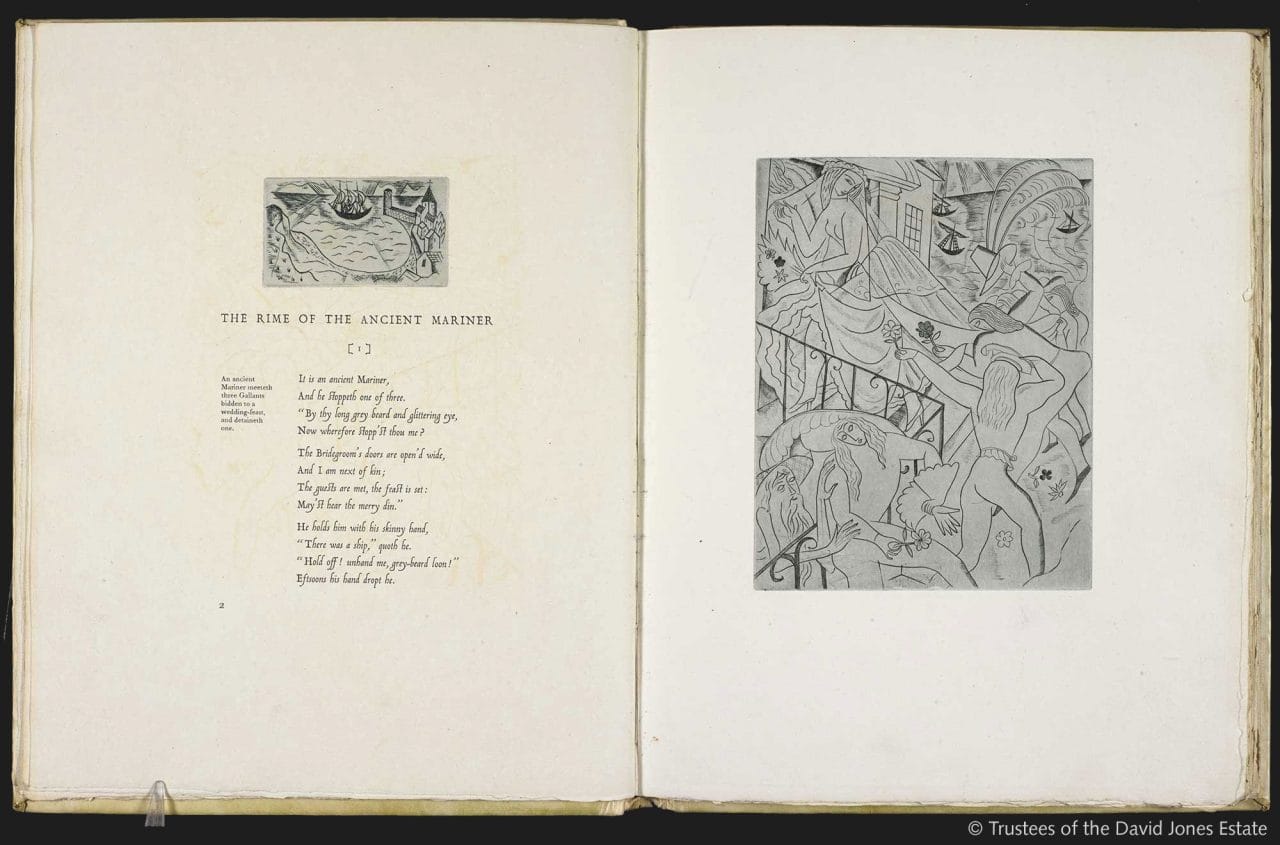

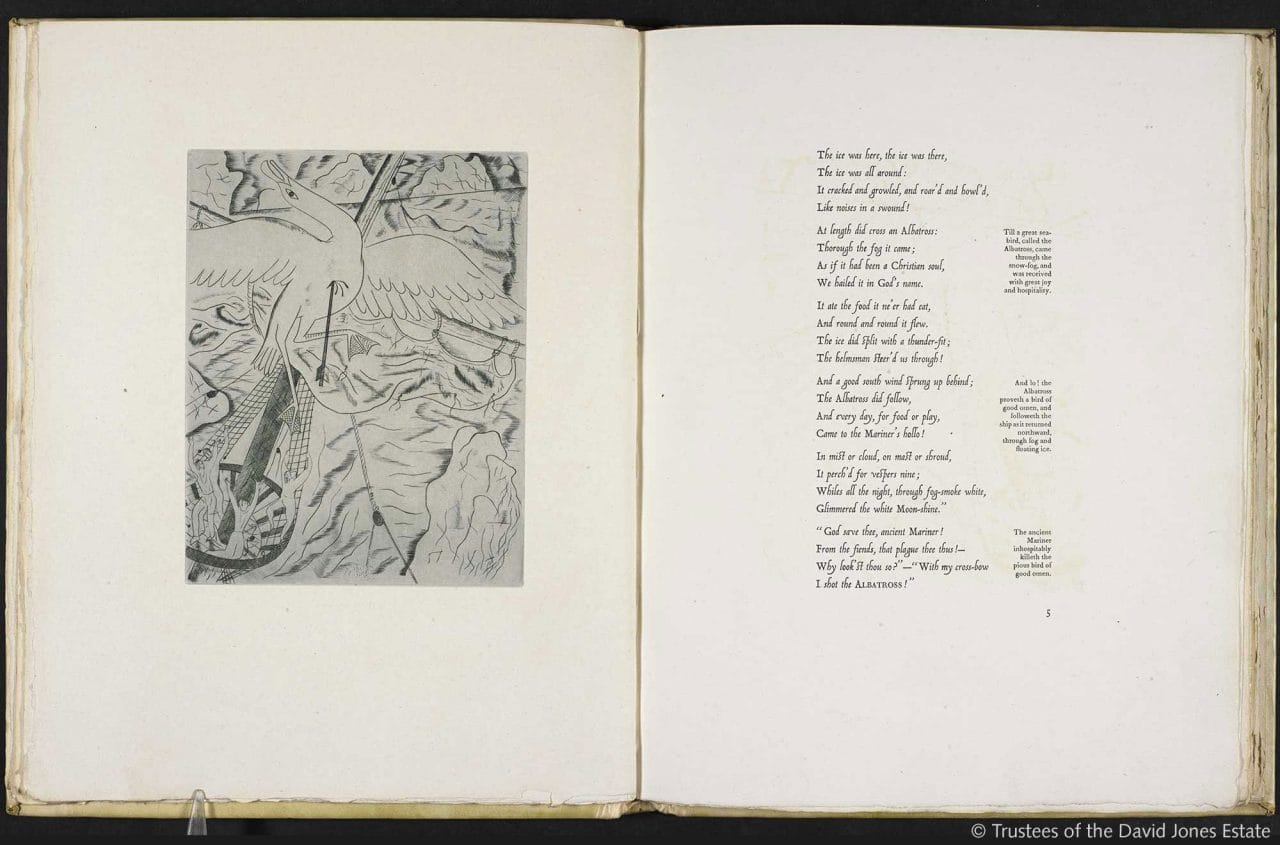

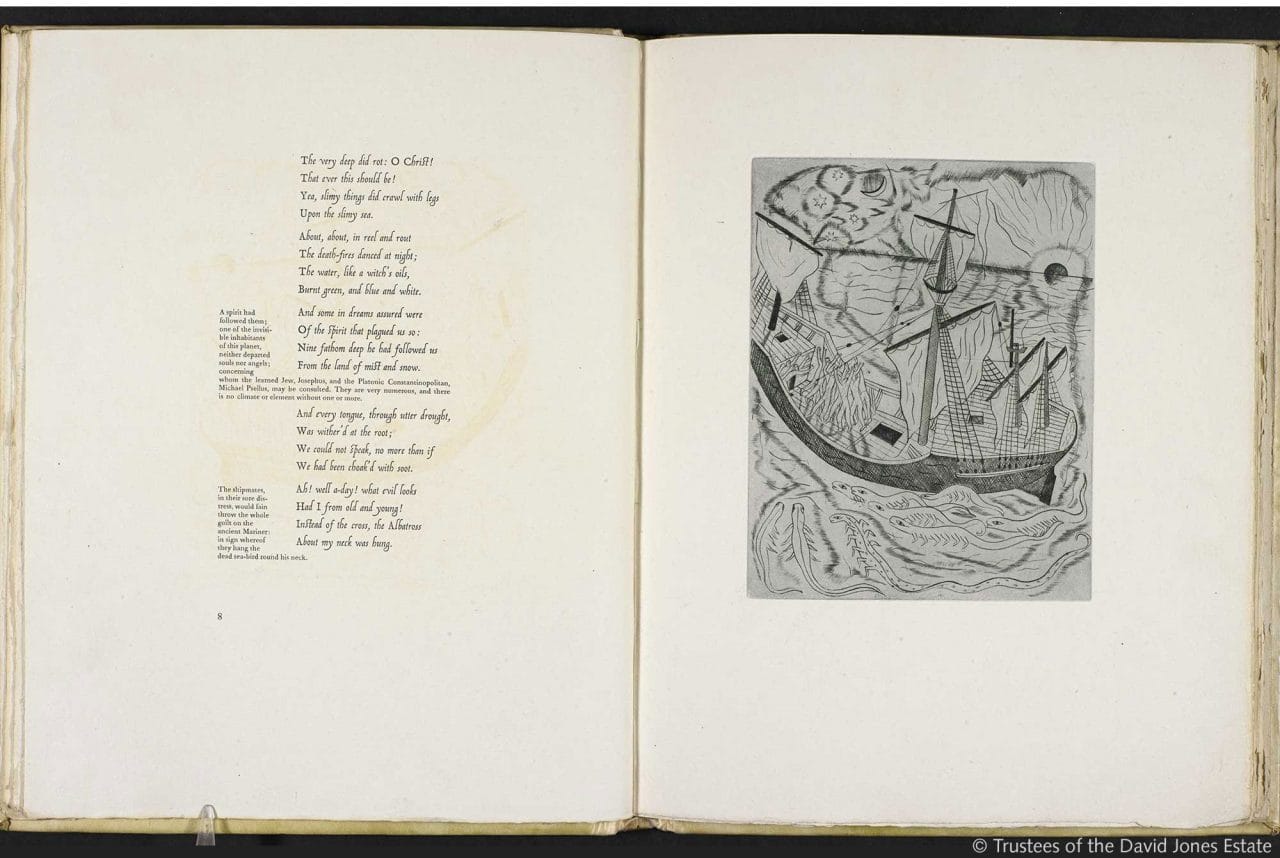

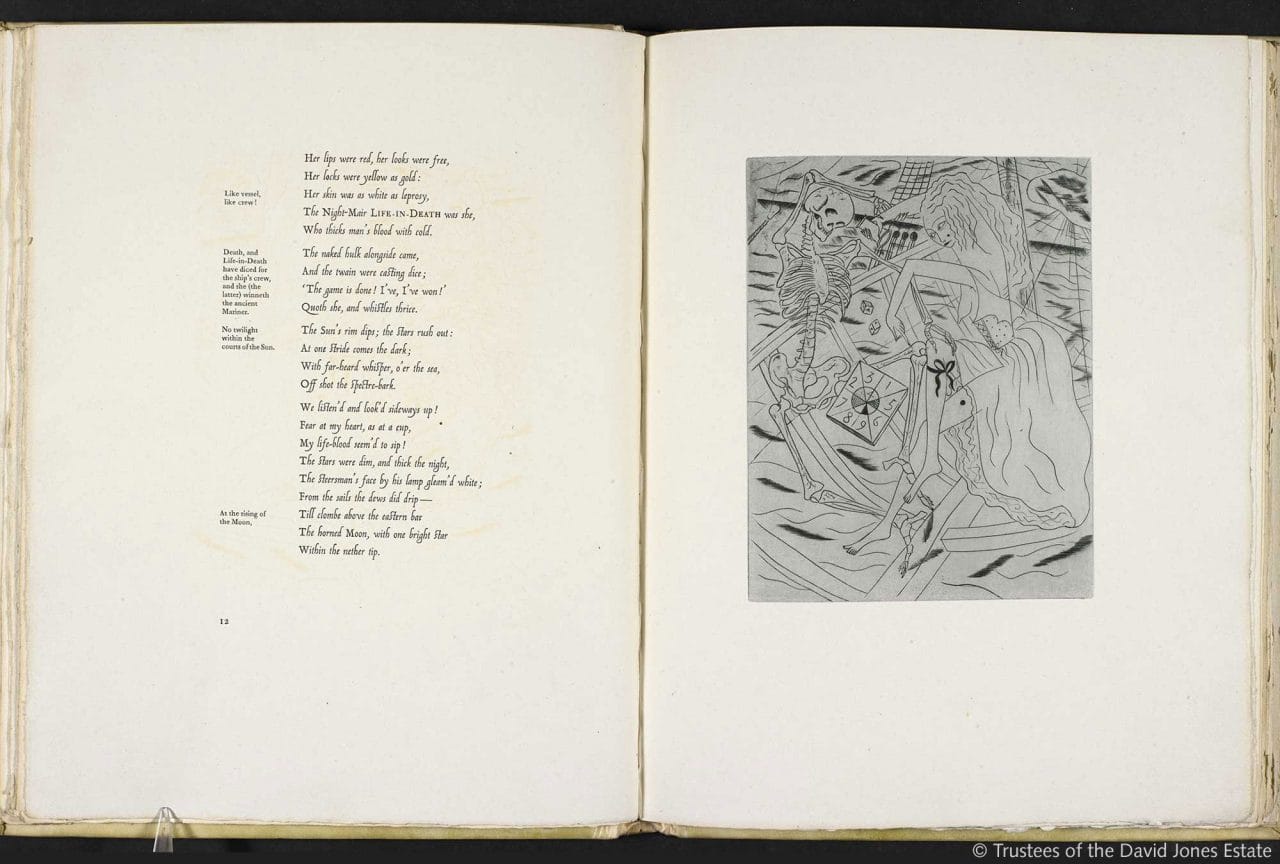

Coleridge often linked poetry to dreams, and maintained that the imagination was equally active in both. His dreams were at times fuelled by his use of opium. After initially using the drug as a medical treatment, he spent much of his life trying to manage his addiction while continuing to use it to control his ill-health. He was much given to disturbing dreams, and connected them to his physical state, thus establishing a physical/dream/poetry relationship. Thoughts in dreams could easily be ‘translated into sights and sensible impressions’.[1] Given Coleridge’s interest in the imagined image it is no wonder ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ has such a strong visual aspect, and that it has inspired some of the greatest book illustrators. David Jones (1895–1974) produced a set of copperplate engravings for the 1929 edition. They usually contain notable elements of Christian symbolism – the priest with his censer, for example, in this illustration for the wedding scene – but a strong Celtic influence is also apparent in the beautiful, simple elegance of his figures.