A new exhibition celebrating the famous Chinese poet, scholar and artist Mu Xin, and his love affair with English literature. Featuring manuscript of Virginia Woolf, Oscar Wilde, Lord Byron and Charles Lamb.

Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway

出版日期: 1886 文学时期: Modernist

In her fourth novel, Mrs Dalloway (1925), the modernist writer Virginia Woolf took on the subject of the English middle classes in the aftermath of the 1914–18 war. She noted in her diary that she wanted ‘to give life & death, sanity & insanity; I want to criticise the social system, & to show it at work, at its most intense’. Set in London during the early 1920s, the novel captures the fast-changing world in which Woolf was working, from transformations in gender roles, sexuality and class divisions to new innovations such as cars, airplanes and cinema.

Mrs Dalloway and the everyday

Set on a single day in June 1923, Mrs Dalloway charts the experiences of various isolated individuals as they move across the bustling capital. Two characters provide the main focus for the novel: the privileged, socially elite Clarissa Dalloway, and Septimus Warren Smith, a shell-shocked veteran of the First World War.

The novel begins with the line ‘Mrs Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself’ as she spends the day preparing for a party, and ends with the party taking place in the evening, when she hears in passing of Septimus’s suicide. However, the book takes us out of any strict temporal frame by incorporating the desires, anxieties, dreams and moments of reminiscence from a number of characters.

By featuring their internal feelings, Woolf allows her characters’ thoughts to travel back and forth in time, reflecting and refracting their emotional experiences. This device creates complex portraits of individuals and their relationships.

From Septimus’s past we learn that his social class ruled him out of going to university; he was ‘one of those half-educated, self-educated men whose education is all learnt from books borrowed from public libraries’, and his desire to be a poet ultimately led him to enlist in the army, as if to defend an idealised Shakespearean England. Woolf’s treatment of the inadequate psychiatric care he receives – Septimus kills himself when he learns he is being committed to a sanatorium – perhaps drew on her own experience of mental illness.

Mrs Dalloway’s more gentle, upper-class regrets and sense of alienation provide a kind of counter-rhythm. Her daughter, Elizabeth, is inescapably symbolic of Clarissa’s own young womanhood, and she is reminded of paths in love and life she didn’t take by her old suitor Peter Walsh, and by the entrancing bohemian Sally Seton (whom she once kissed) who has now married a provincial businessman.

Professor Elaine Showalter explores modernity, consciousness, gender and time in Virginia Woolf’s ground-breaking work, Mrs Dalloway. The film is shot around the streets of London, as well as at the British Library and at Gordon Square in Bloomsbury where Virginia and her siblings lived in the early 20th century. The film offers rare glimpses into the manuscript draft of the novel.

Finding a modern voice

In 1924, in the essay ‘Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown’, Woolf wrote about the arrival of ‘modern’ life in the early 20th century: ‘all human relations have shifted – those between masters and servants, husbands and wives, parents and children. And when human relations change there is at the same time a change in religion, conduct, politics, and literature’.

Modernity, as defined by Woolf, was a society and culture in flux – everyday life was fragmentary and unstable. She recognised that in order to depict this kaleidoscopic experience, writers had to find new forms and themes. Like a Cubist painting, Woolf’s techniques allow her to describe the city and the people within it from multiple perspectives.

The main characters in Mrs Dalloway raise issues of deep personal concern for Woolf: in Clarissa, the repressed social and economic position of women, and in Septimus, the treatment of those driven by depression to the borderlands of sanity. Woolf’s work often explored her fascination with the marginal and overlooked. In ‘The Art of Biography’ (1939), she argued that ‘The question now inevitably asks itself, whether the lives of great men only should be recorded. Is not anyone who has lived a life, and left a record of that life, worthy of biography – the failures as well as the successes, the humble as well as the illustrious’.

About stream of consciousness

The term ‘stream of consciousness’ was first used in a literary sense by May Sinclair in her 1918 review of a novel by Dorothy Richardson. Other authors well known for this style include Katherine Mansfield, William Faulkner and James Joyce.

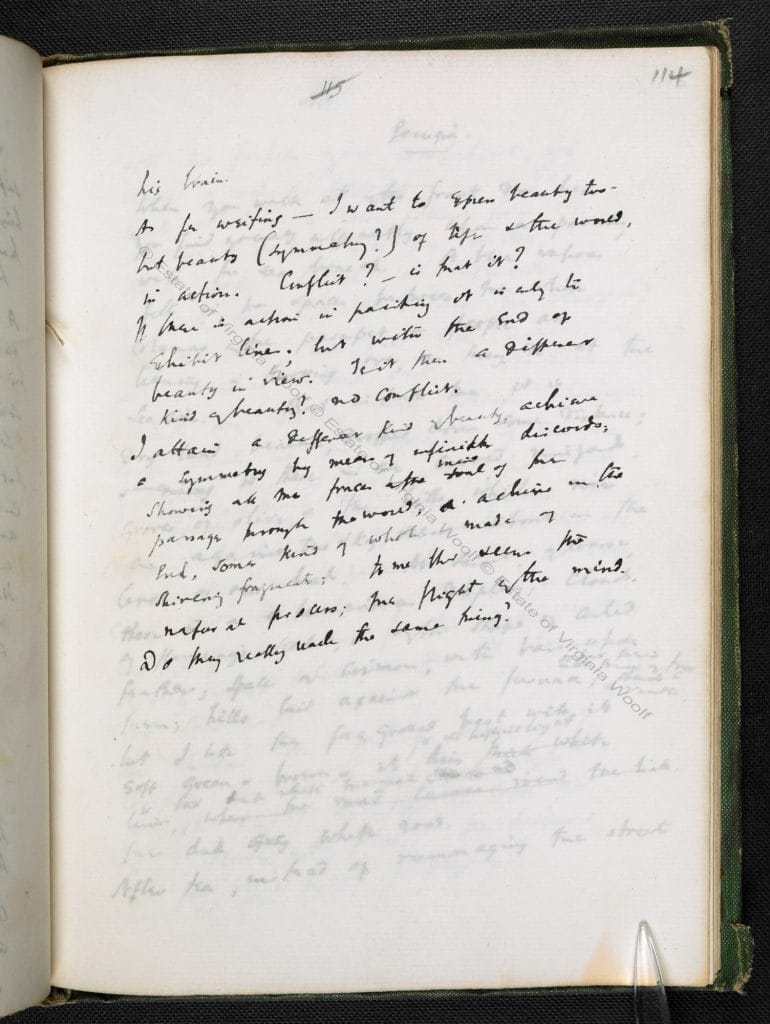

Stream of consciousness is a style of writing evolved by authors in the early 20th century to express the flow of a character’s thoughts and feelings. The technique aims to give readers the impression of being inside the mind of the character – an internal view that illuminates the character’s motivation, psychological complexity and the fragmented experience of living in the modern world. Thoughts spoken aloud are not always the same as those ‘on the floor of the mind’, as Woolf put it. In a diary entry from 1908, Woolf lays out an early concept of this technique, describing a wish to ‘attain a different kind of beauty, achieve a symmetry by means of infinite discords; showing all the traces of the mind’s passage through the world; achieve in the end, some kind of whole made of shivering fragments; to me this seems the natural process; the flight of the mind…’

London and the First World War

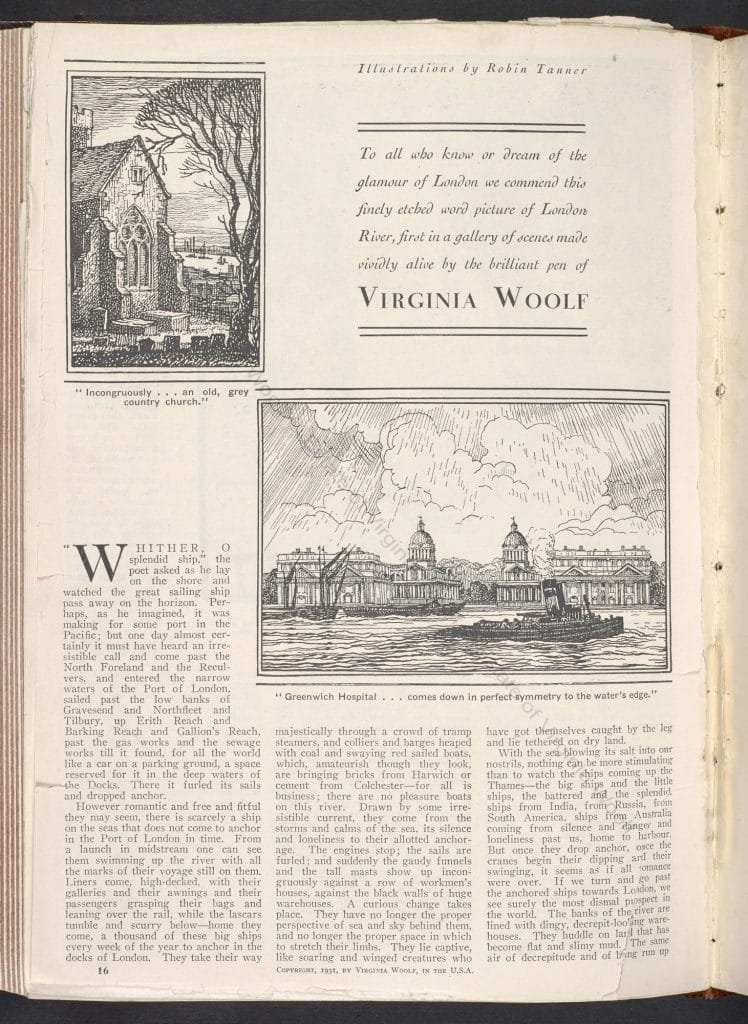

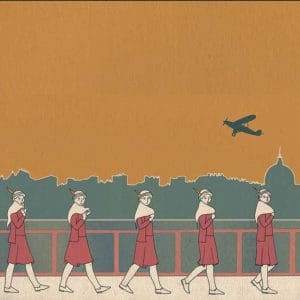

Mrs Dalloway is set in the city of London five years after the end of the First World War. The devastating impact of warfare is still visible in the fabric of the city and the minds of its inhabitants. The grief and trauma left in the wake of the conflict appear in the everyday events the novel depicts.

In its opening pages, for example, we read that an airplane circling over London creates unease in those beneath it, ‘ominously’ bringing to mind the German planes that had attacked the capital. Equally, a glimpse of Mrs Foxcroft ‘at the Embassy last night still eating her heart out because that nice boy was killed’ in the war, enriches our sense of Mrs Dalloway’s status as a war novel of towering importance: ‘This late age of the world’s experience had bred in them all, all men and women, a well of tears’; ‘in all the hat shops and tailors’ shops strangers looked at each other and thought of the dead’. As the mysterious grey car glides through St James’s, it passes, among other onlookers, ‘orphans, widows, the War’.

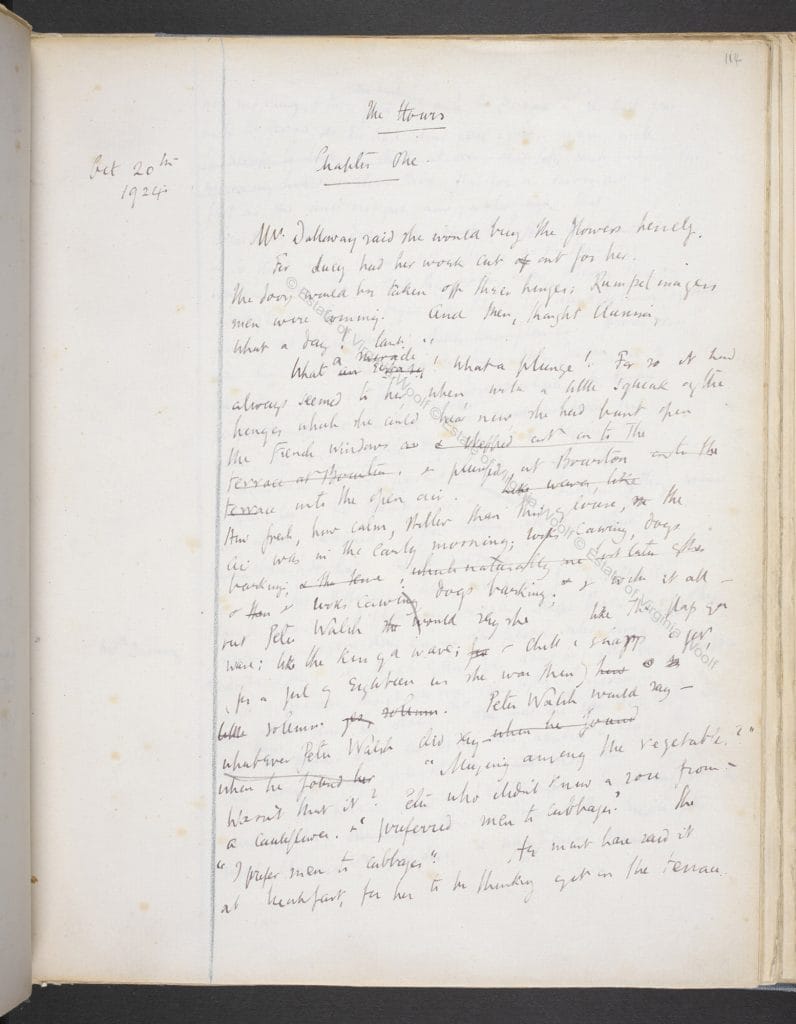

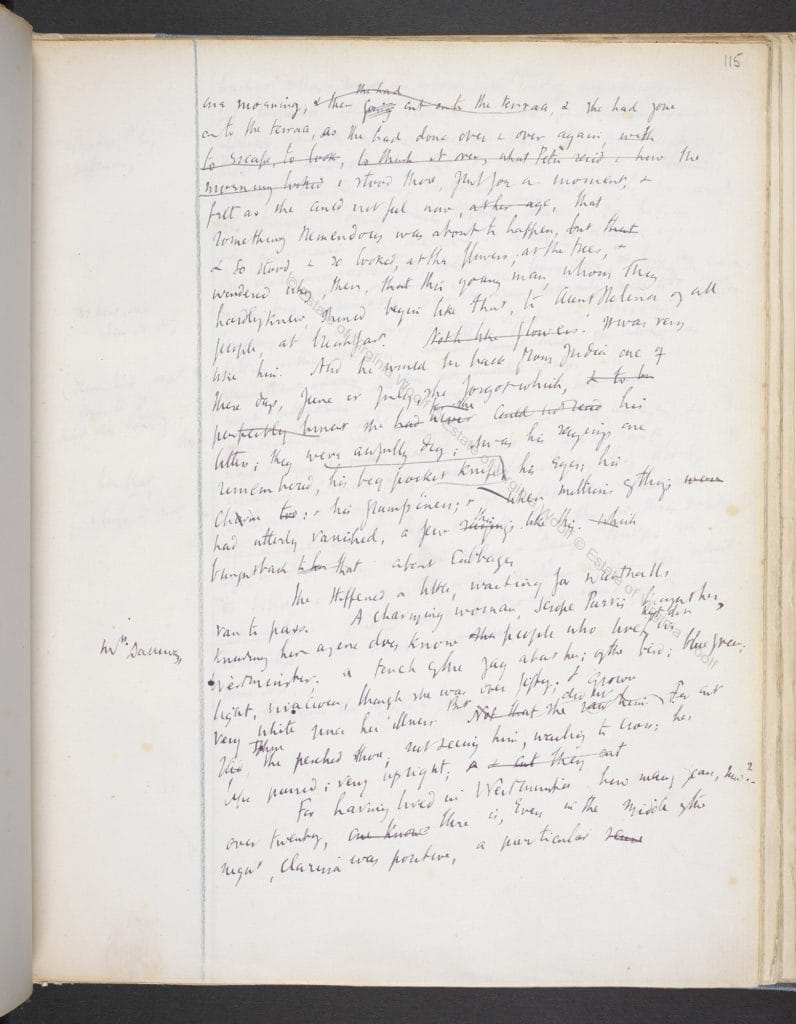

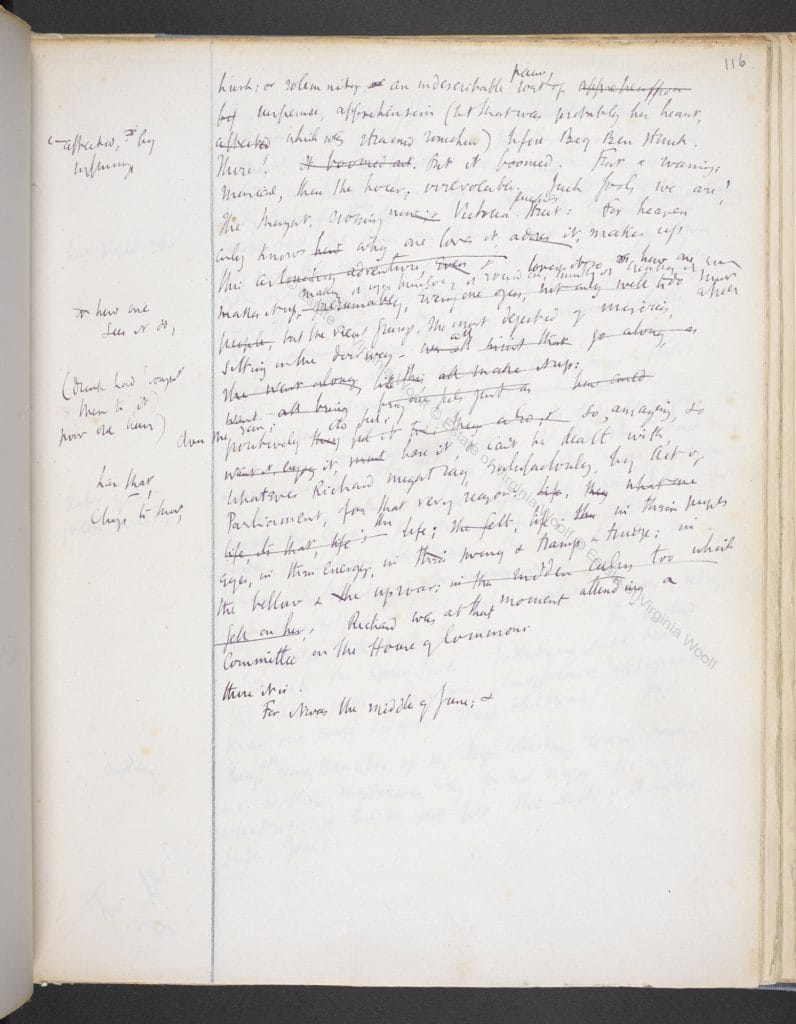

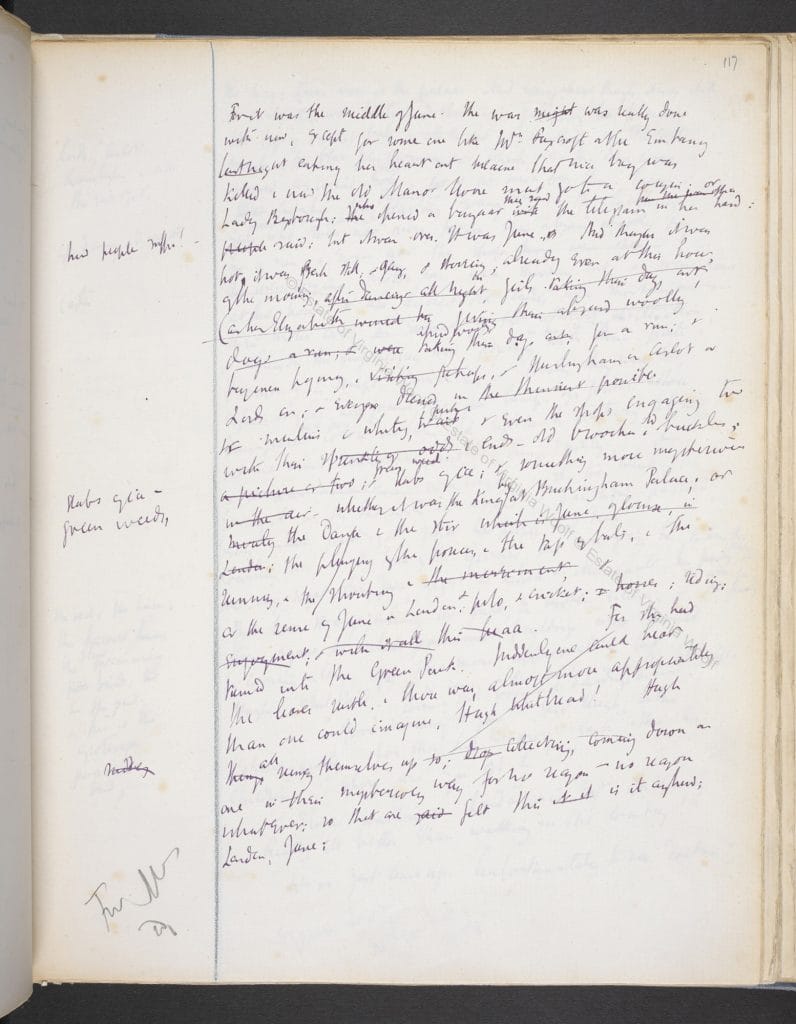

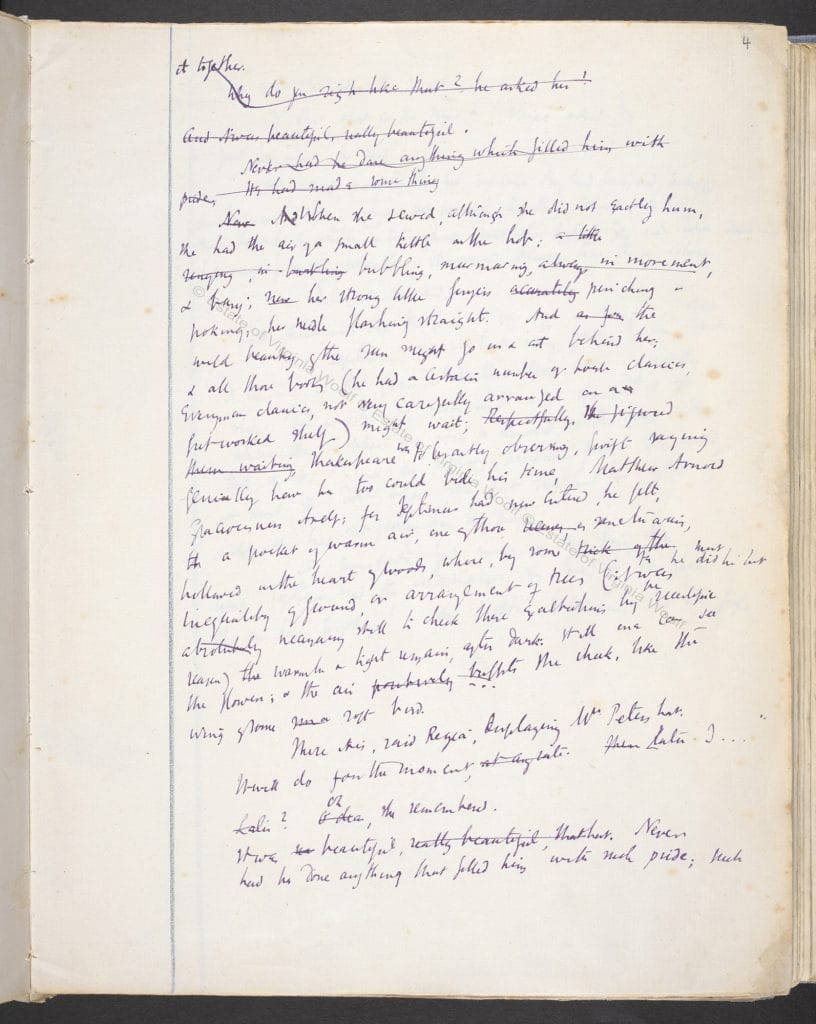

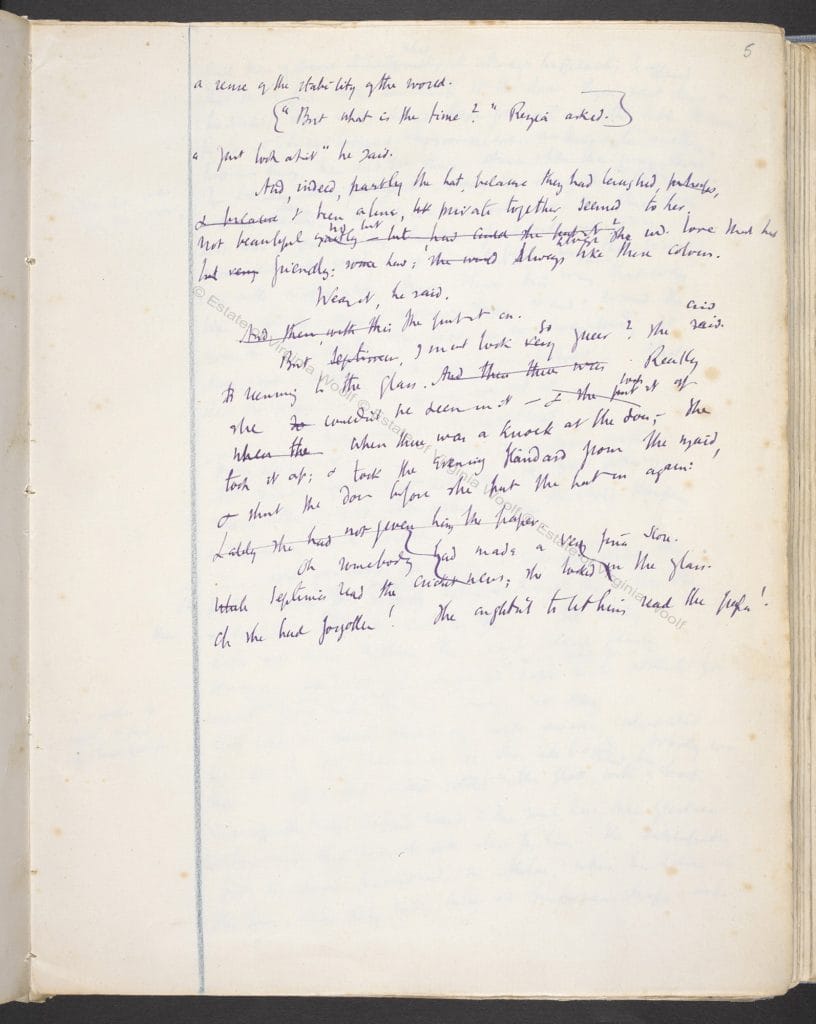

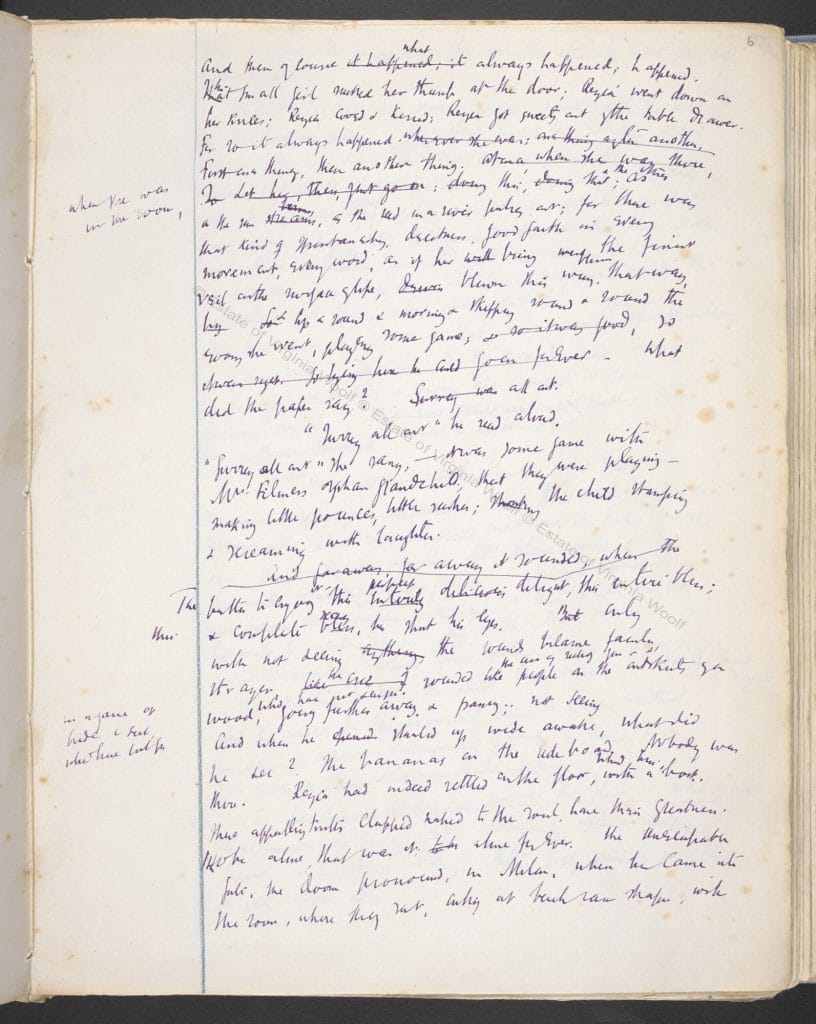

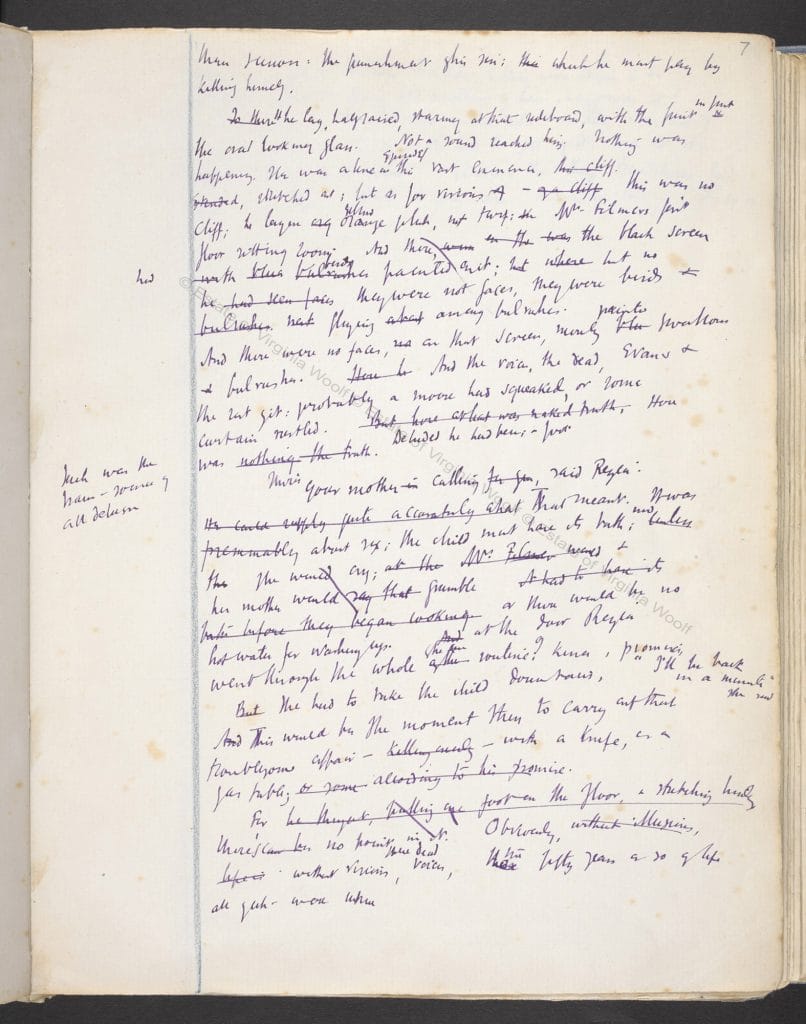

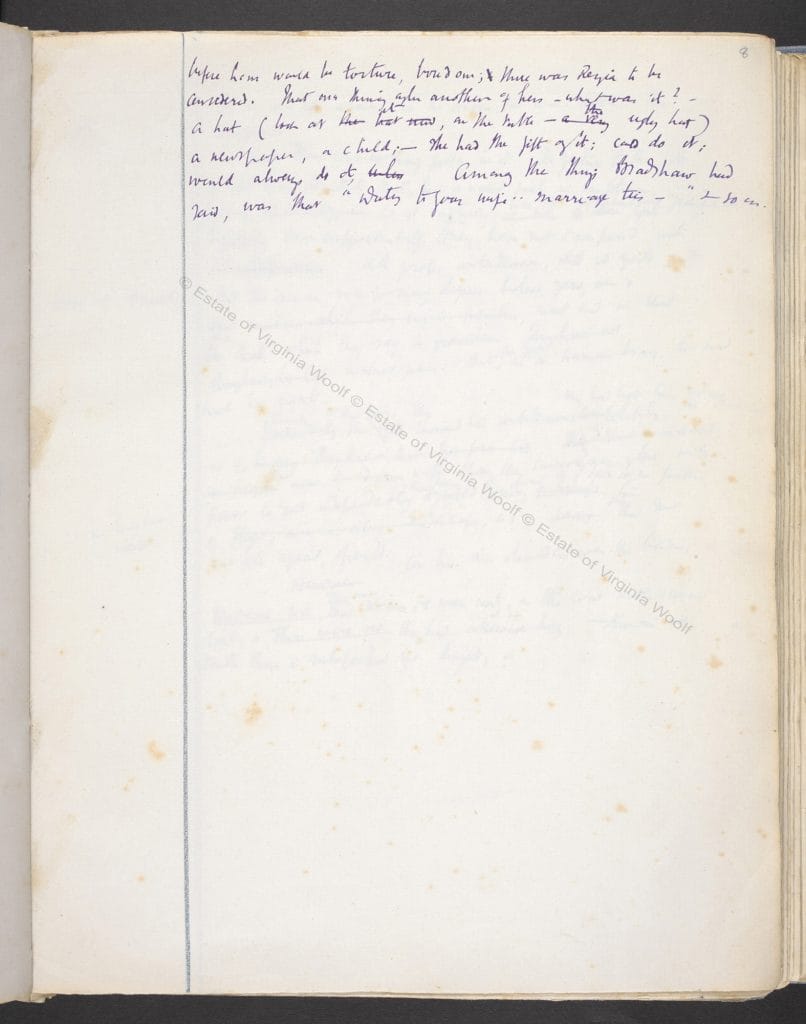

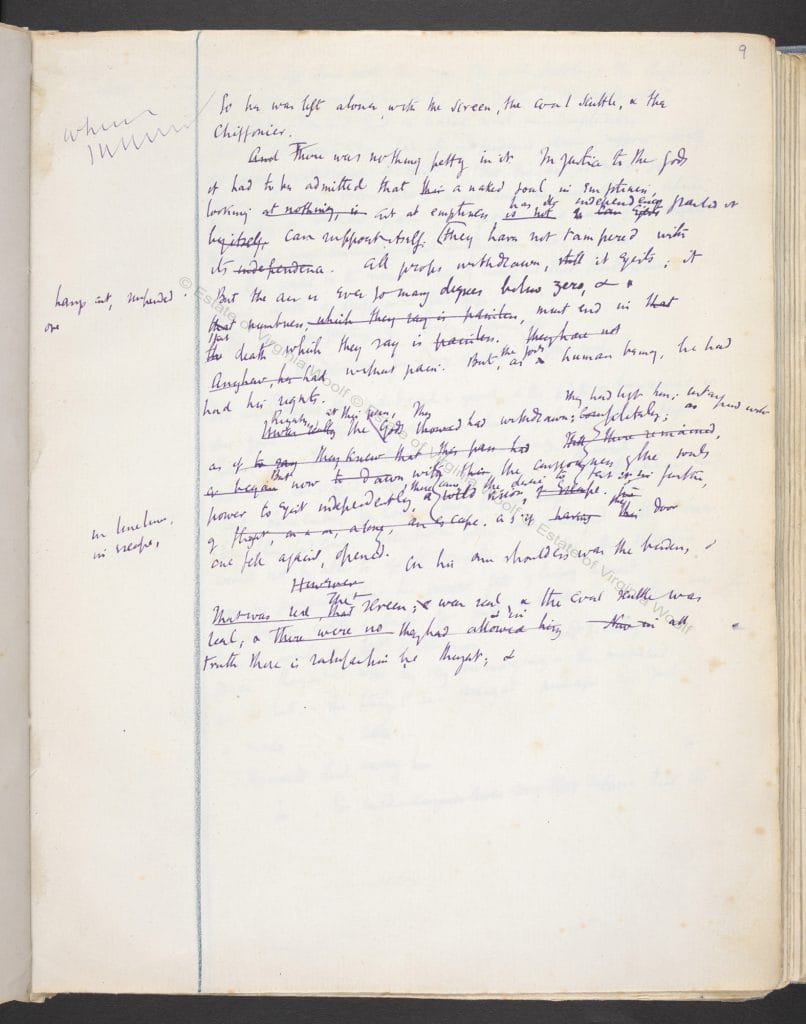

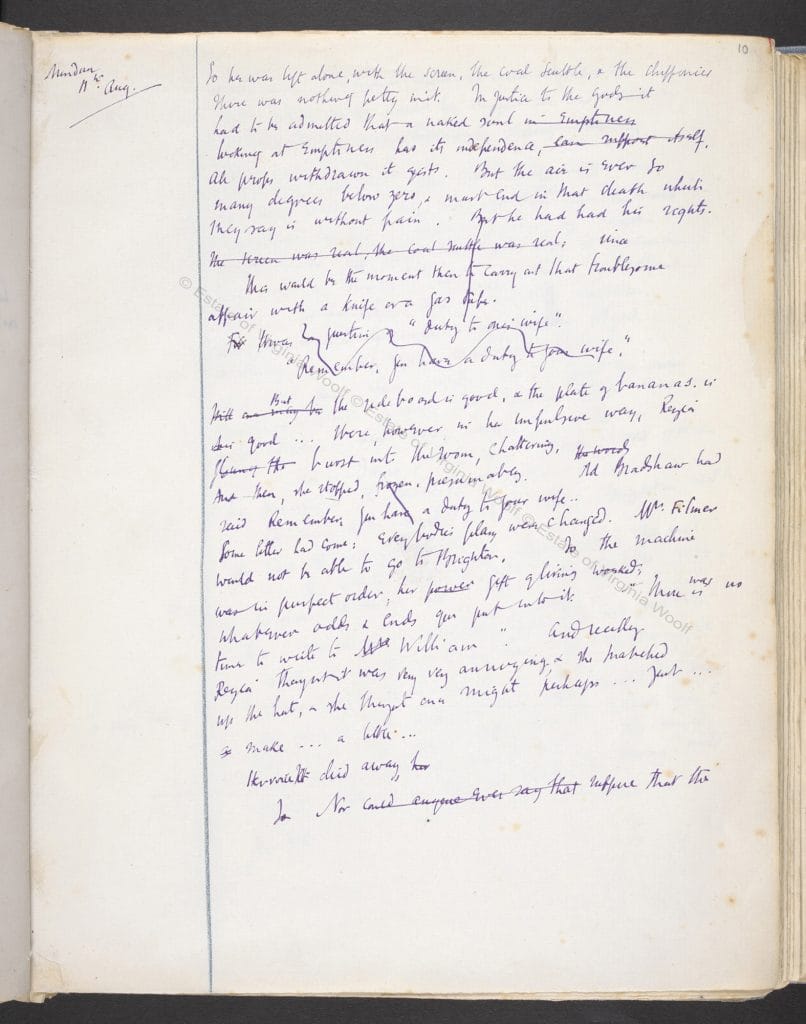

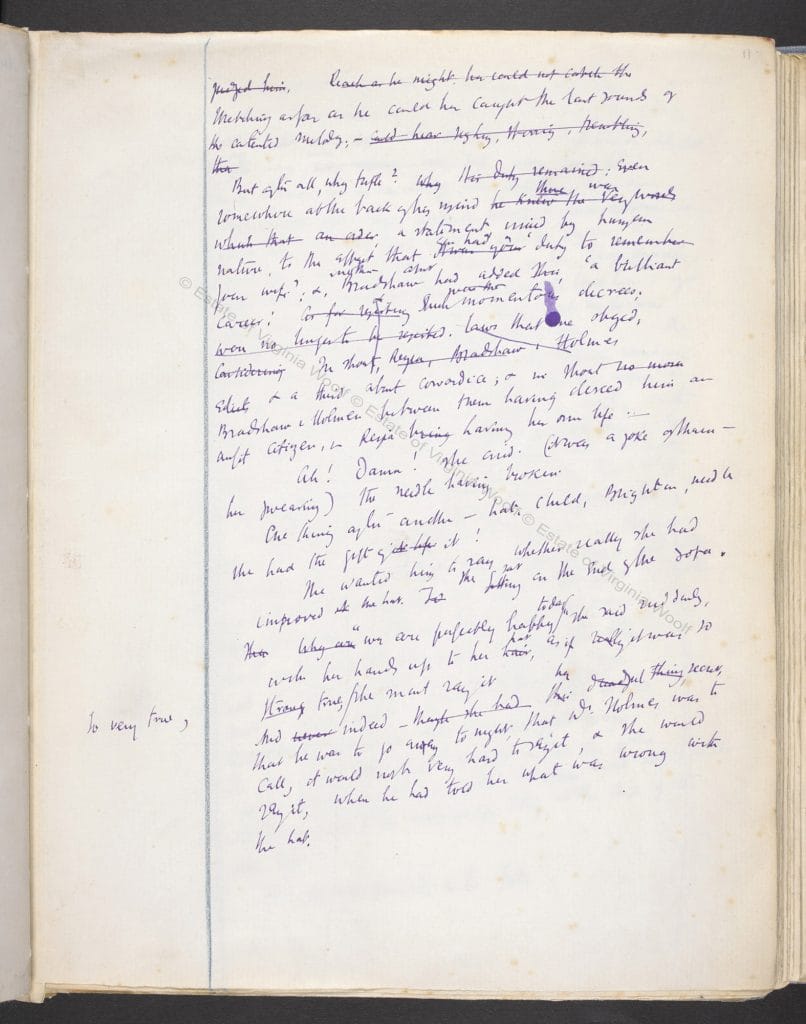

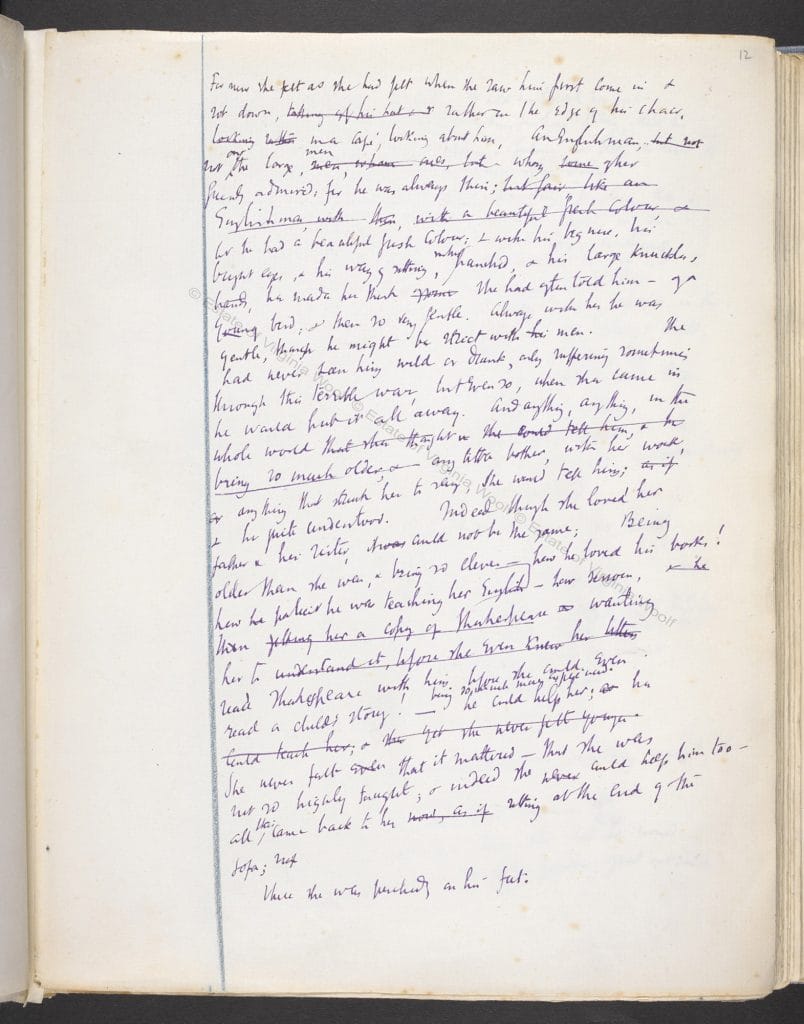

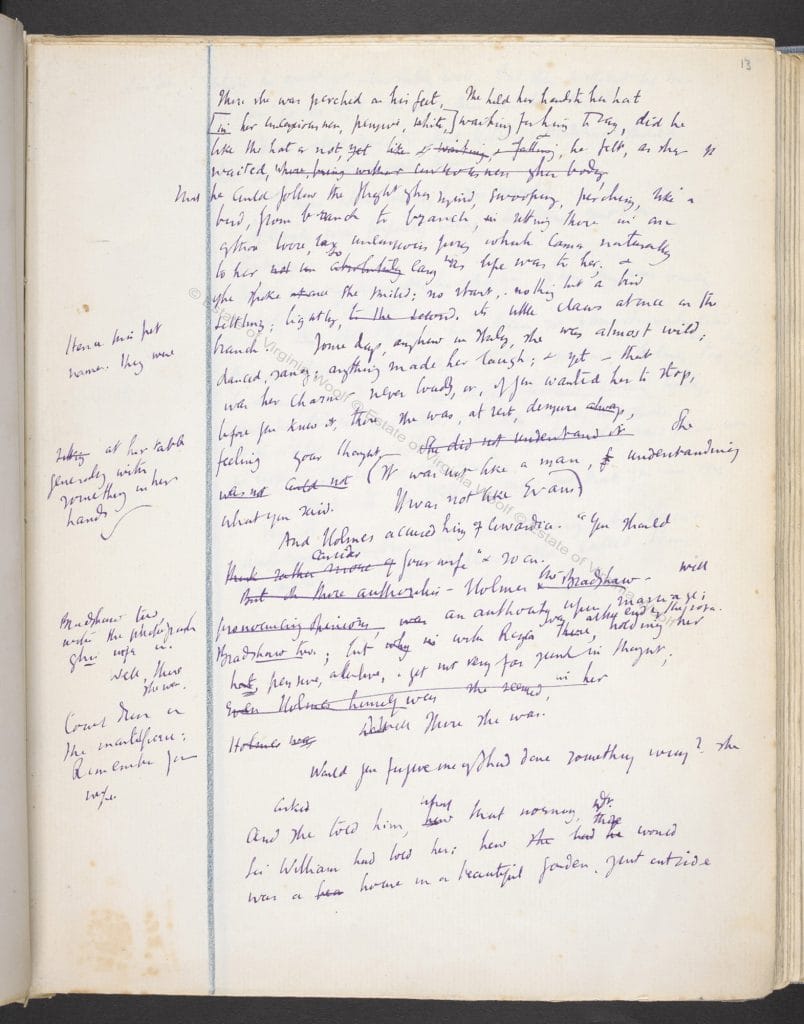

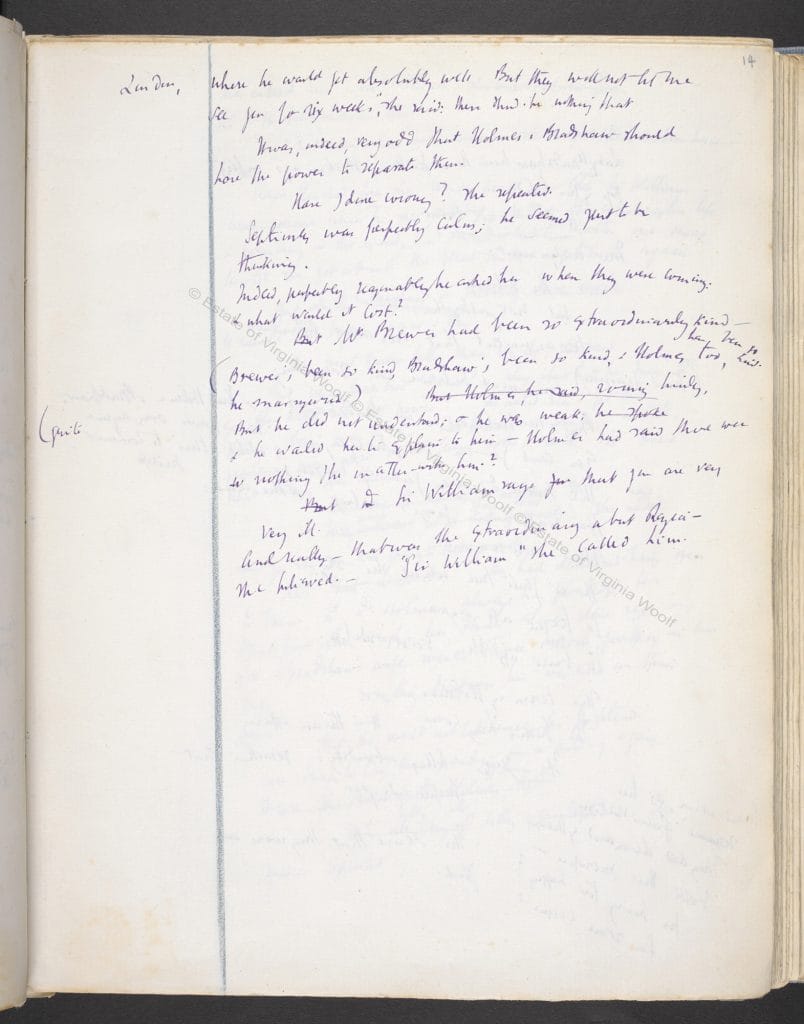

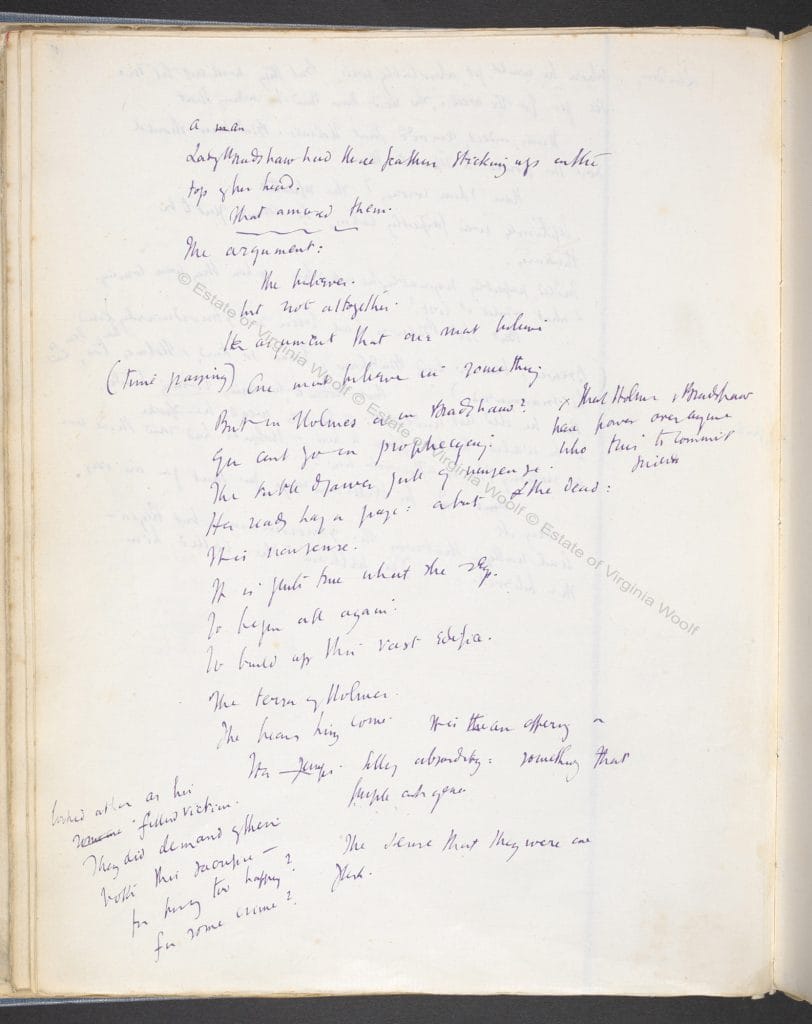

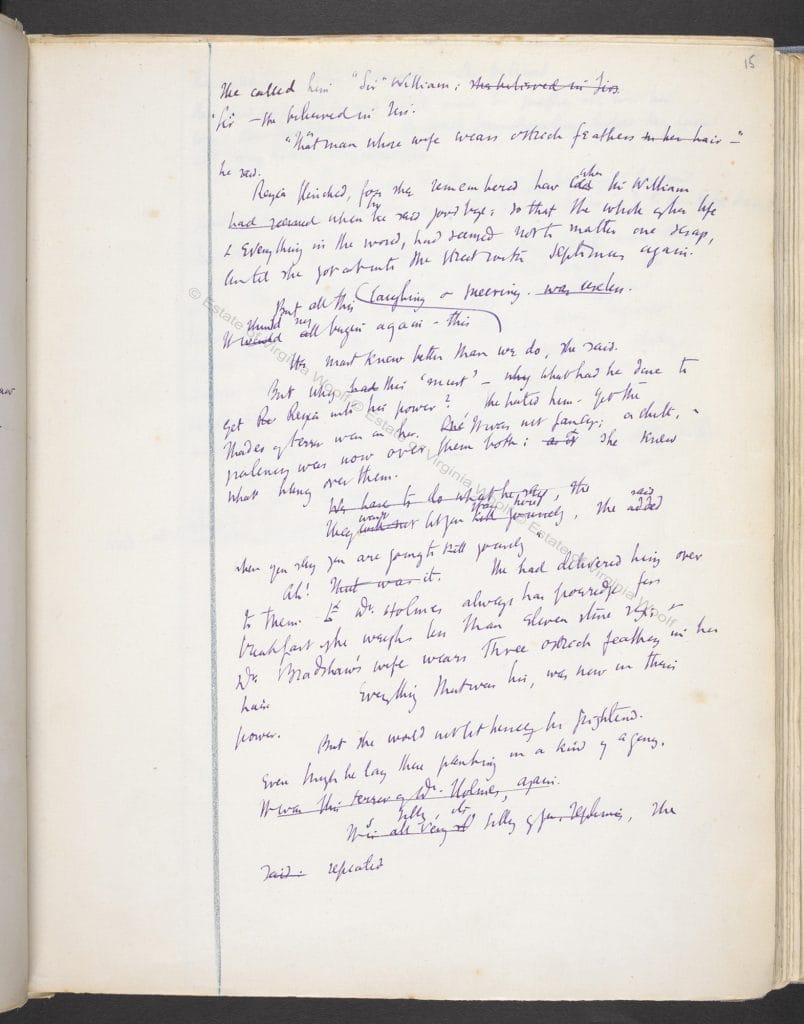

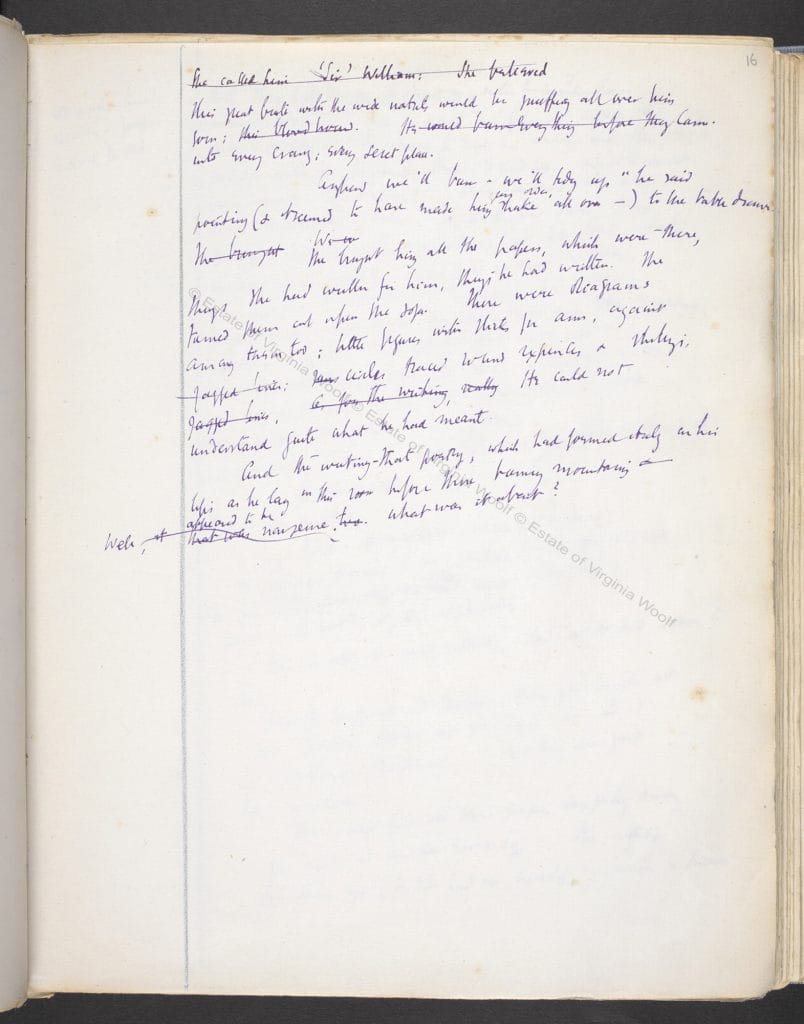

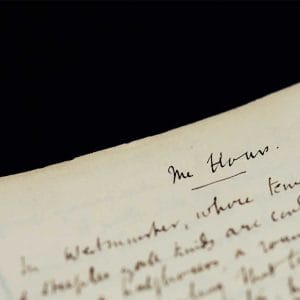

Notebook drafts of Mrs Dalloway

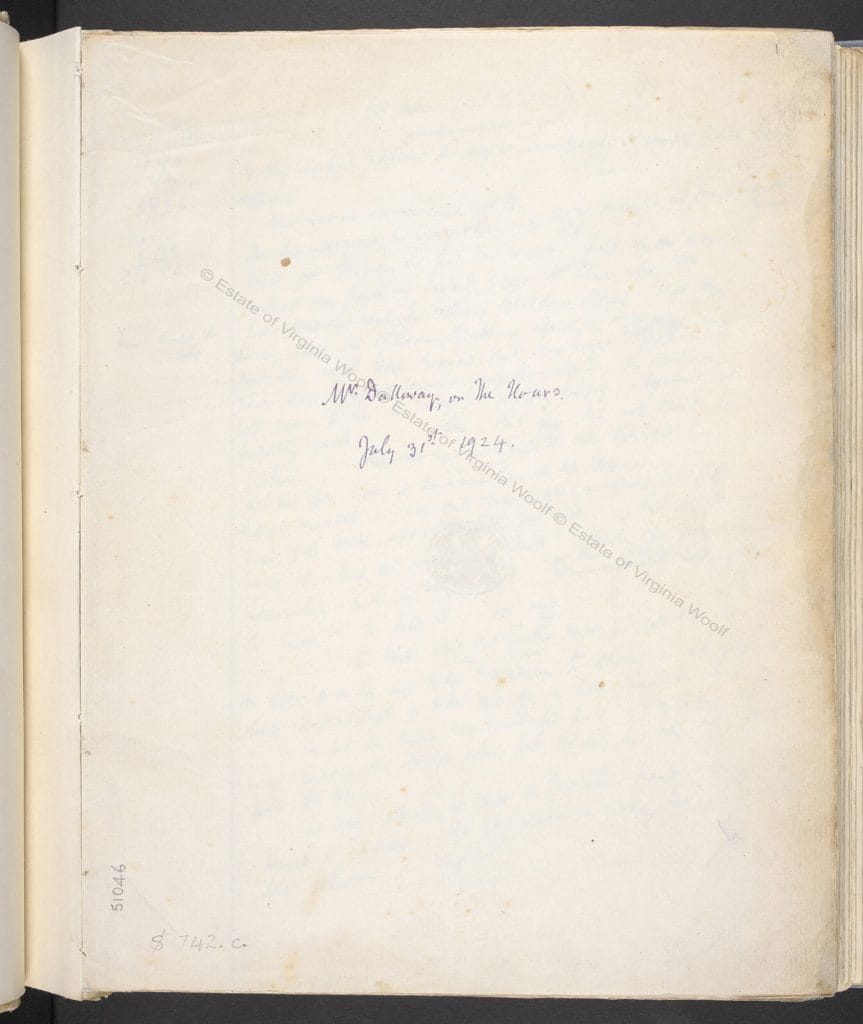

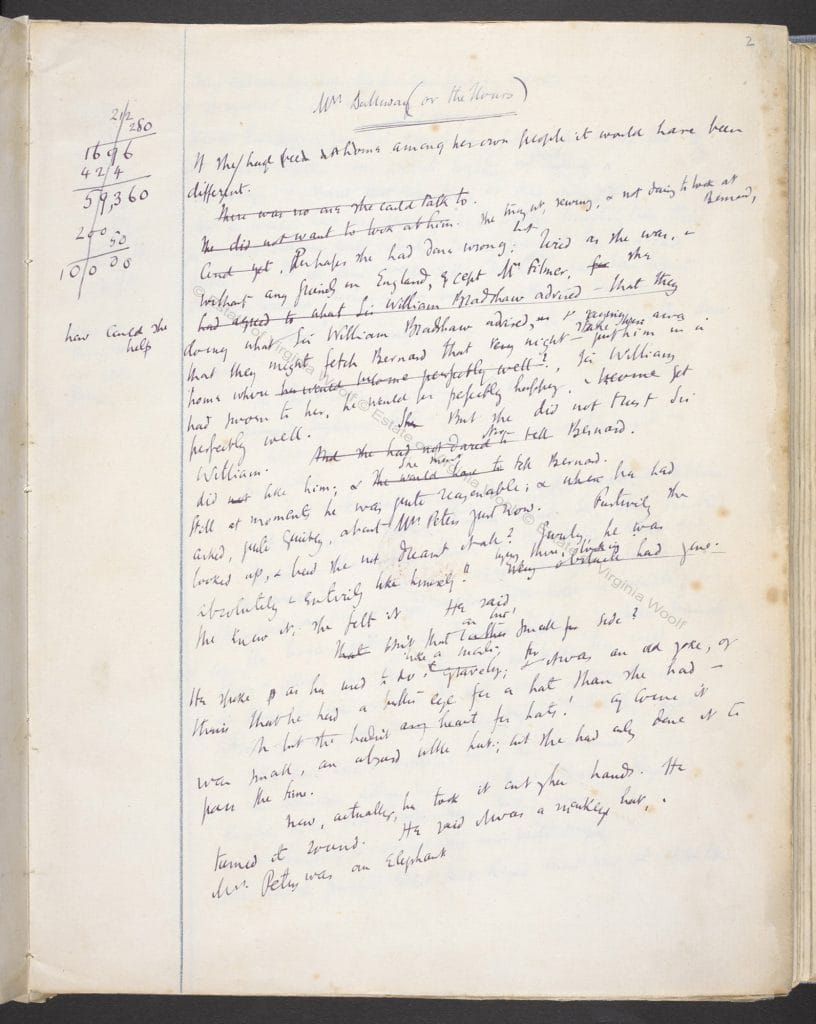

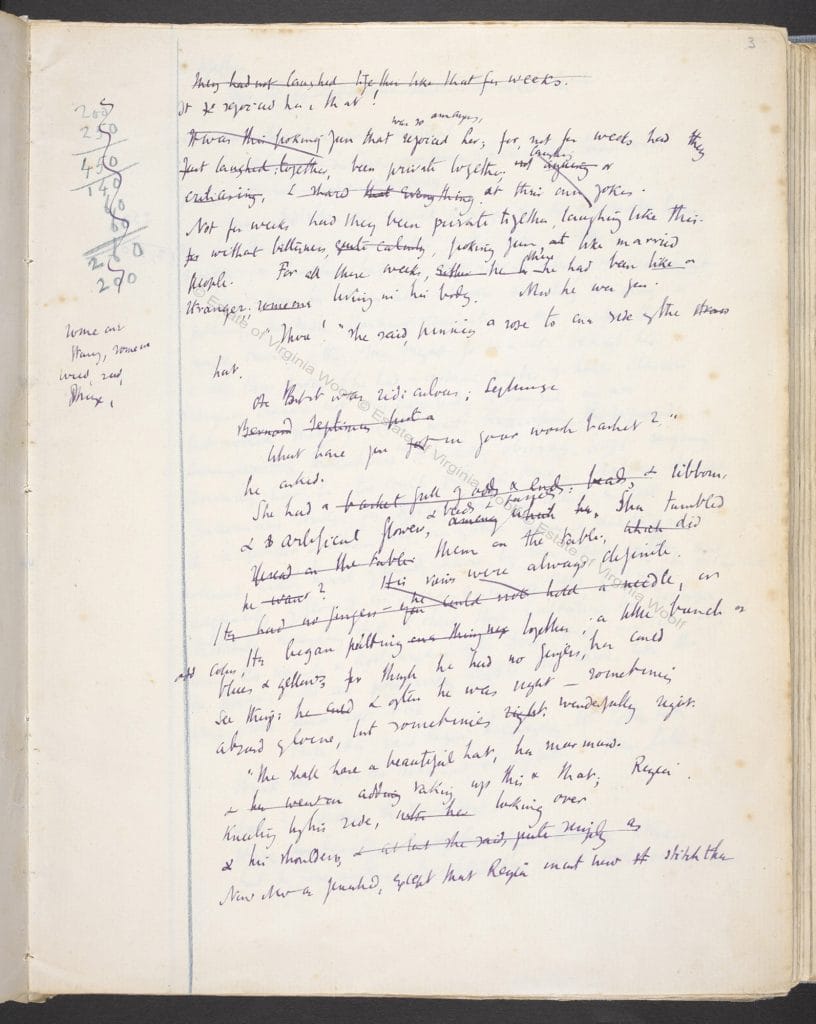

Contained within three notebooks, this is Woolf’s working draft for Mrs Dalloway, originally titled ‘The Hours’. Woolf created the manuscript in June 1923, the month in which the novel is set. The work was published two years later.

The final, published version of 1925 is markedly different to the manuscripts, giving us a unique insight into Woolf’s writing process and the development of the novel. Here, in her own handwriting, we see her xploring and developing the technique of ‘stream of consciousness’, exploring ways to show the multifaceted nature of consciousness, and attempting illustrate the impact of the modern world on the psyche.

Virginia’s Woolf’s other works and legacy

Besides her writing, Woolf had a considerable impact on the cultural life around her. The publishing house she ran with her husband Leonard Woolf, the Hogarth Press, was originally established in Richmond and then in London’s Bloomsbury,an area after which the ‘Bloomsbury Set’ of artists, writers and intellectuals is named. Woolf’s house was a hub for some of the most interesting cultural activity of the time, and Hogarth Press publications included books by writers such as T S Eliot, Sigmund Freud, Katherine Mansfield, E M Forster and the Woolfs themselves.

Woolf refused patriarchal honours like the Companion of Honour (1935) and honorary degrees from Manchester and Liverpool (1933 and 1939). She wrote polemical works about the position of women in society, such as A Room of One’s Own (1929) and Three Guineas (1938). In Flush (1933) she wrote of the life of the spaniel owned by the poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning, in Orlando (1928) she fictionalised the life of her friend Vita Sackville-West into that of a man-woman, born in the Renaissance but surviving till the present day.

Born Virginia Adeline Stephen in 1882, her parents were Leslie Stephen (1832–1904), the founder of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, and his second wife, Julia Duckworth (1846–1895). Woolf’s father – who was later knighted for services to literature – gave her the run of his substantial library. Her mother, father and brother died in quick succession, and she suffered from poor mental health for much of her life, committing suicide in 1941.