The Lambs’ Tales from Shakespeare

出版日期: 1807 类型: Children's Literature

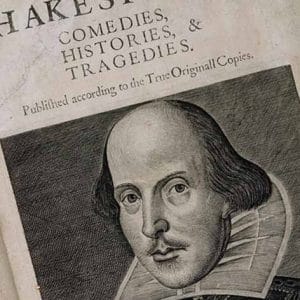

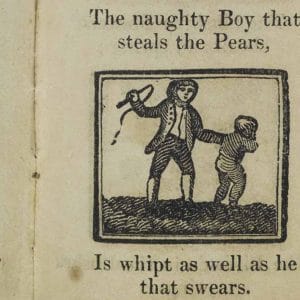

A collection of 20 short stories designed to bring Shakespeare’s plays to life for young readers, Tales from Shakespeare is one of the most loved children’s books of all time, on a par with Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland and Kenneth Grahame’s Wind in the Willows. Created by the brother and sister duo Charles and Mary Lamb (though only Charles was credited when the book first appeared in 1807), Tales has never been out of print in English, and has been translated into at least 40 languages worldwide – including Chinese, where it became sensationally popular in the early 1900s. In the two centuries since Lambs’ Tales were first published, they have given millions of children worldwide their first taste of Shakespeare – and not just kids, for the book remains popular among adult readers, too.

Who were the Lambs?

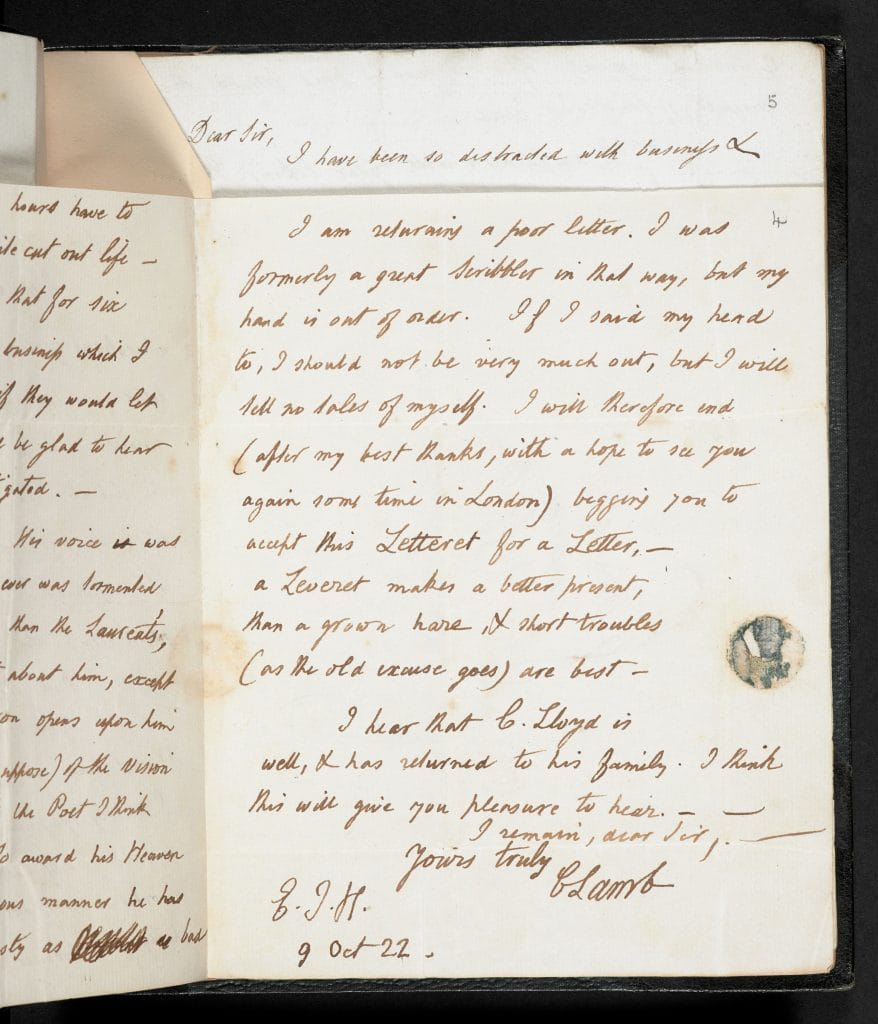

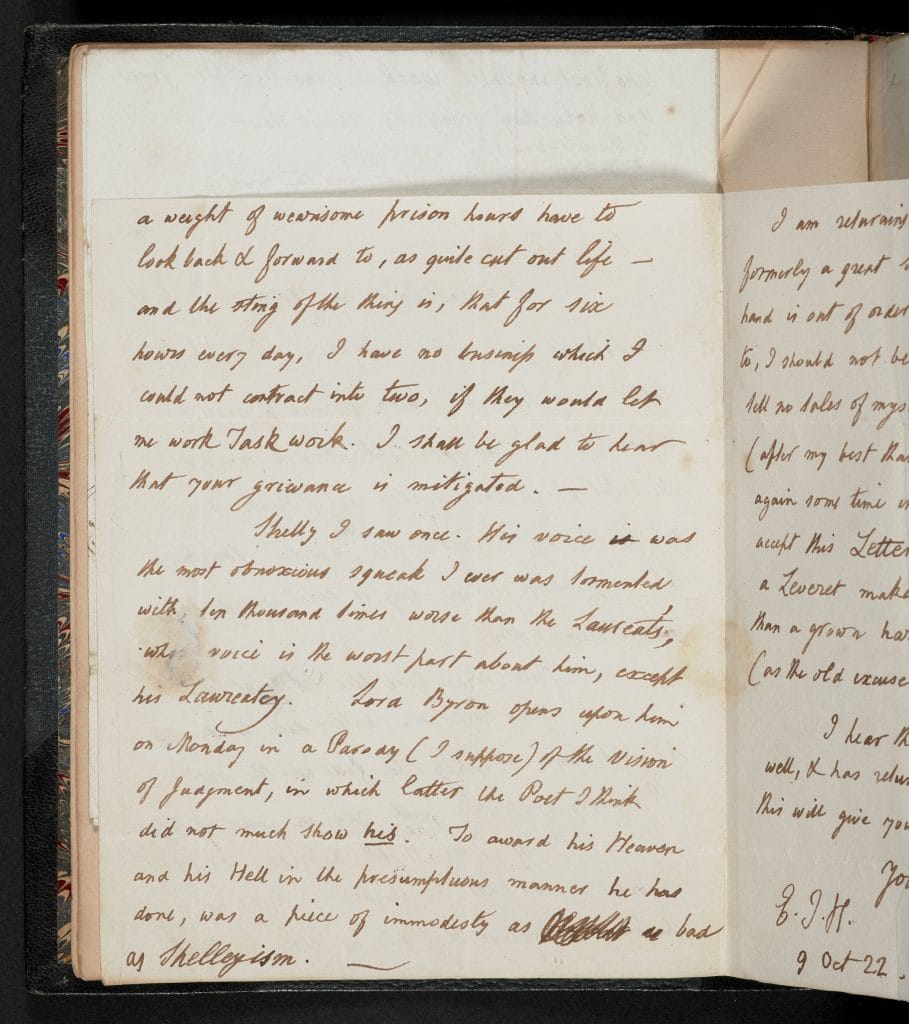

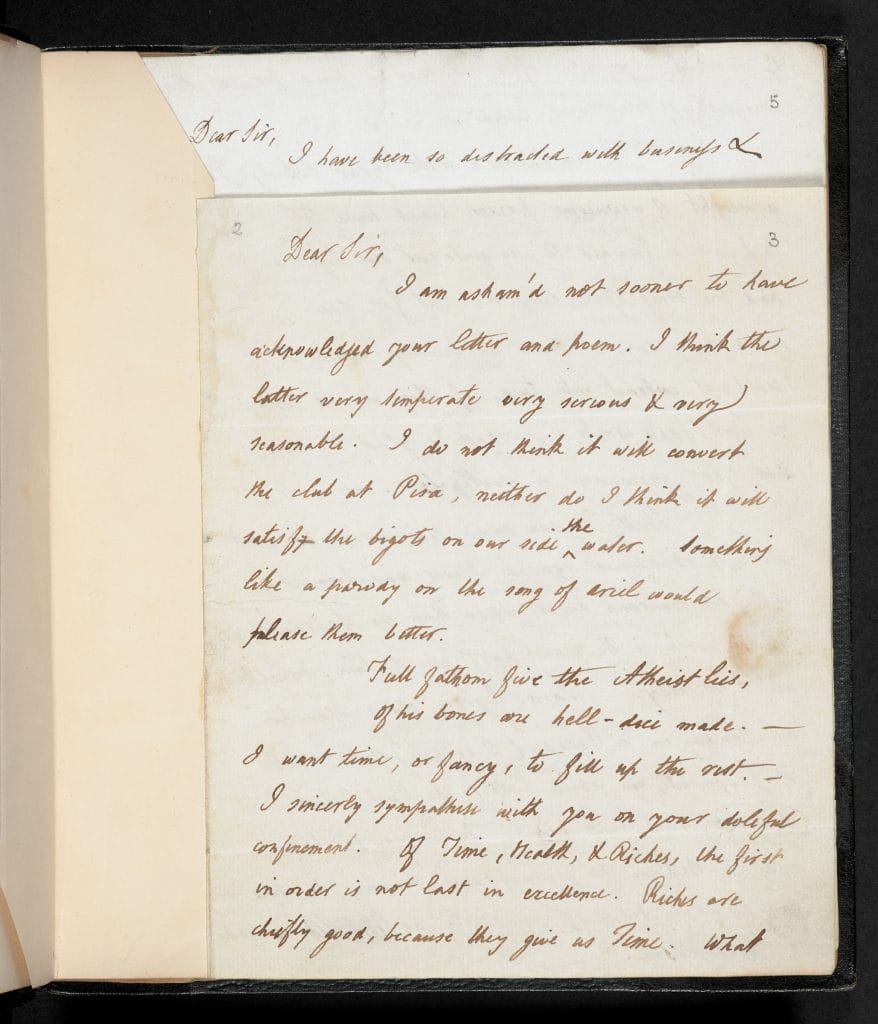

The story of the lives of Mary and Charles Lamb makes for sad reading. Born in 1764 and 1775 respectively into a working-class household in London, they spent their early years struggling to make ends meet. Charles was lucky enough to be sent to Christ’s Hospital charity school in the city, where he became friendly with Samuel Taylor Coleridge (see below), but Mary received little formal education and had to earn money as a seamstress to keep the family afloat. Mental illness dogged both siblings: having become a trainee clerk in the East India Company, Charles had some kind of breakdown in 1795 and spent six weeks in an asylum. But much worse was to follow in September 1796, when Charles came home from work to find that his sister had stabbed their mother to death in a fit of mania and injured their father; only by promising the authorities that he would take her in did Charles manage to stop Mary being permanently incarcerated.

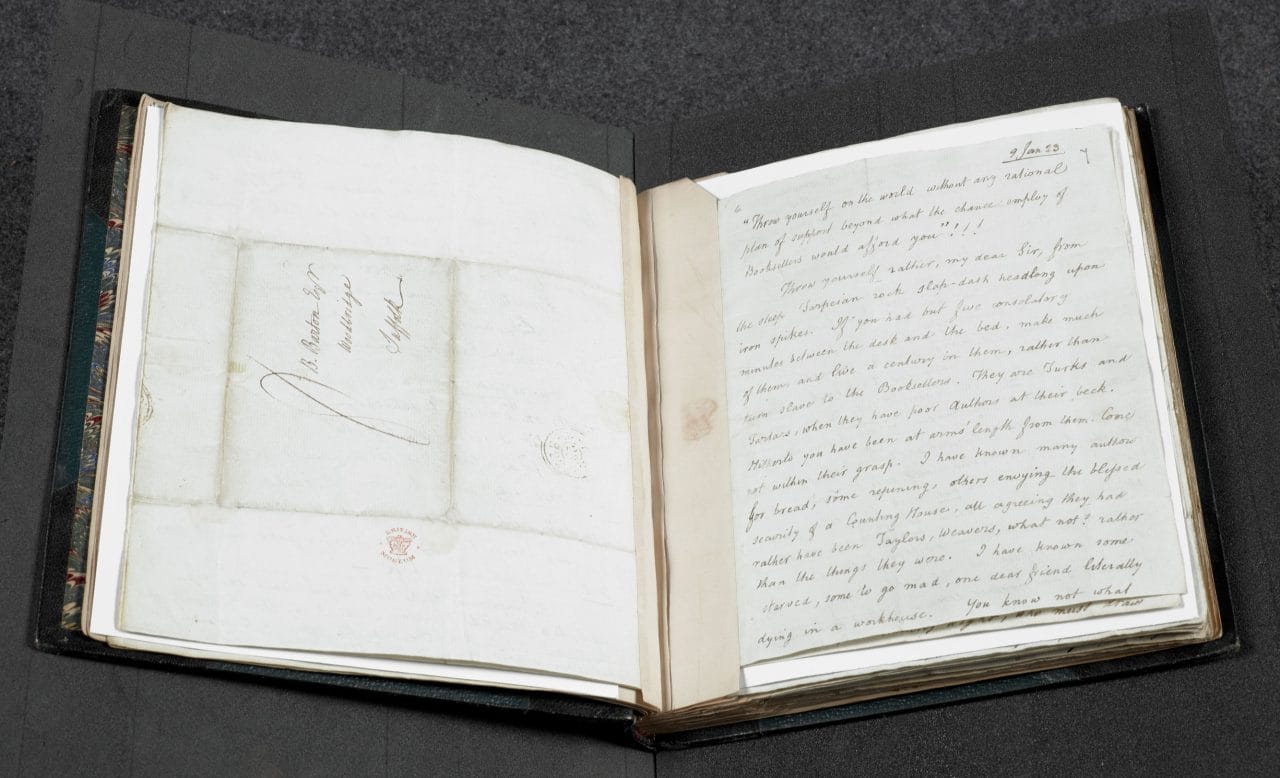

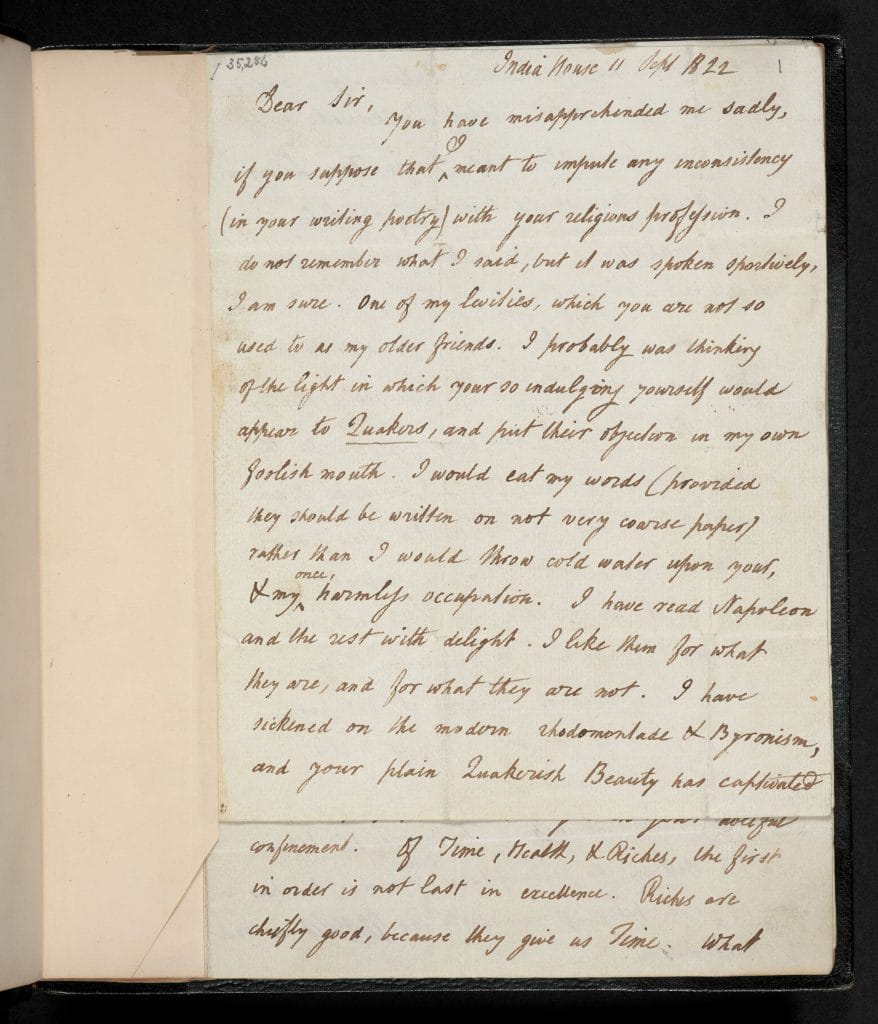

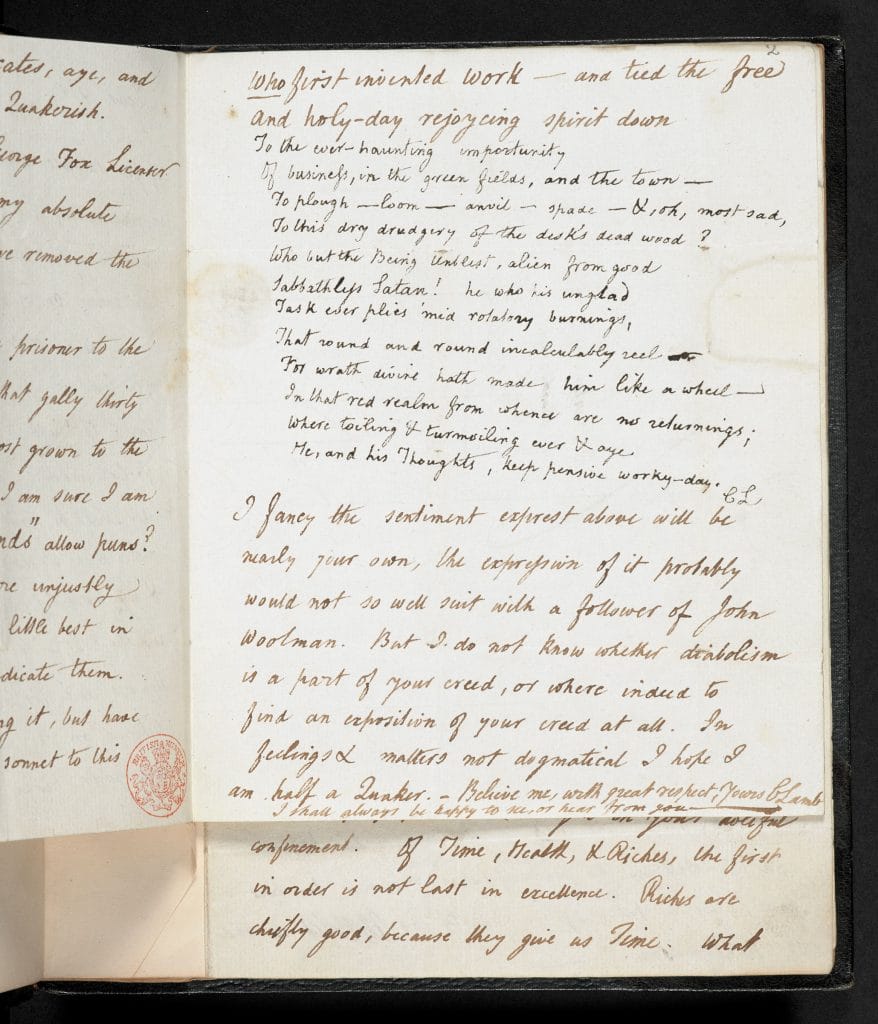

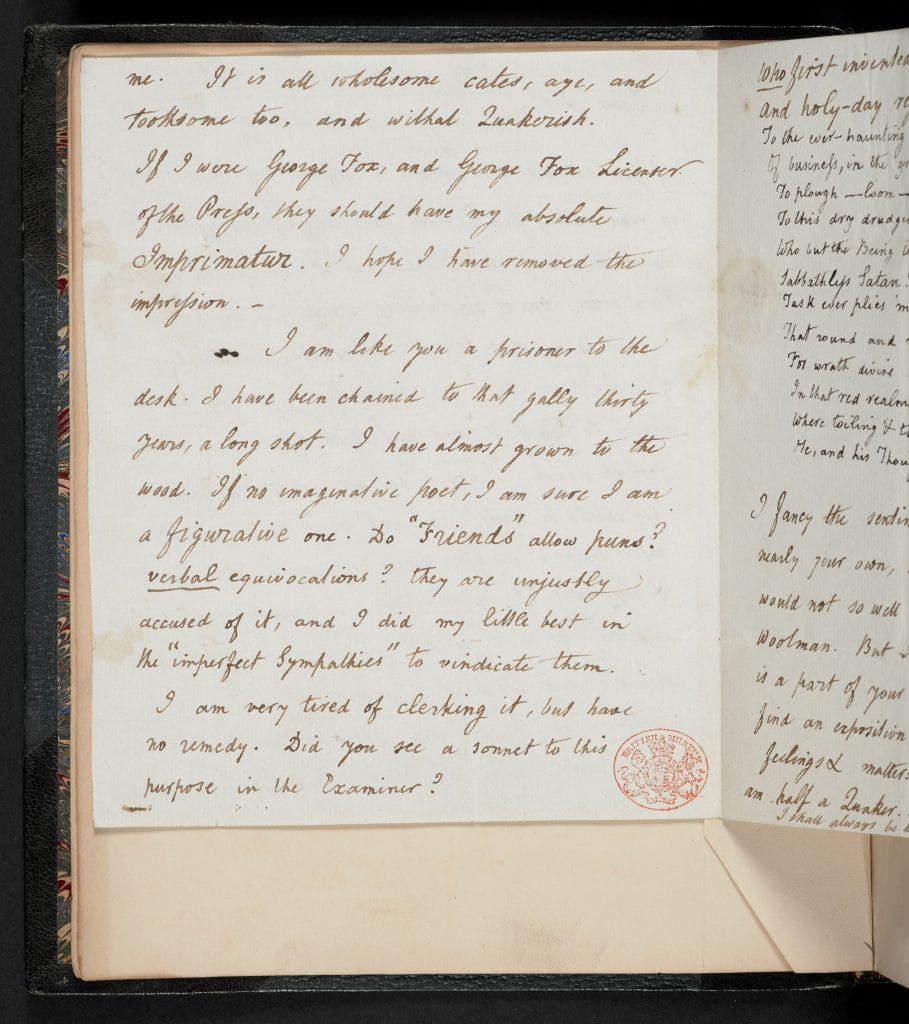

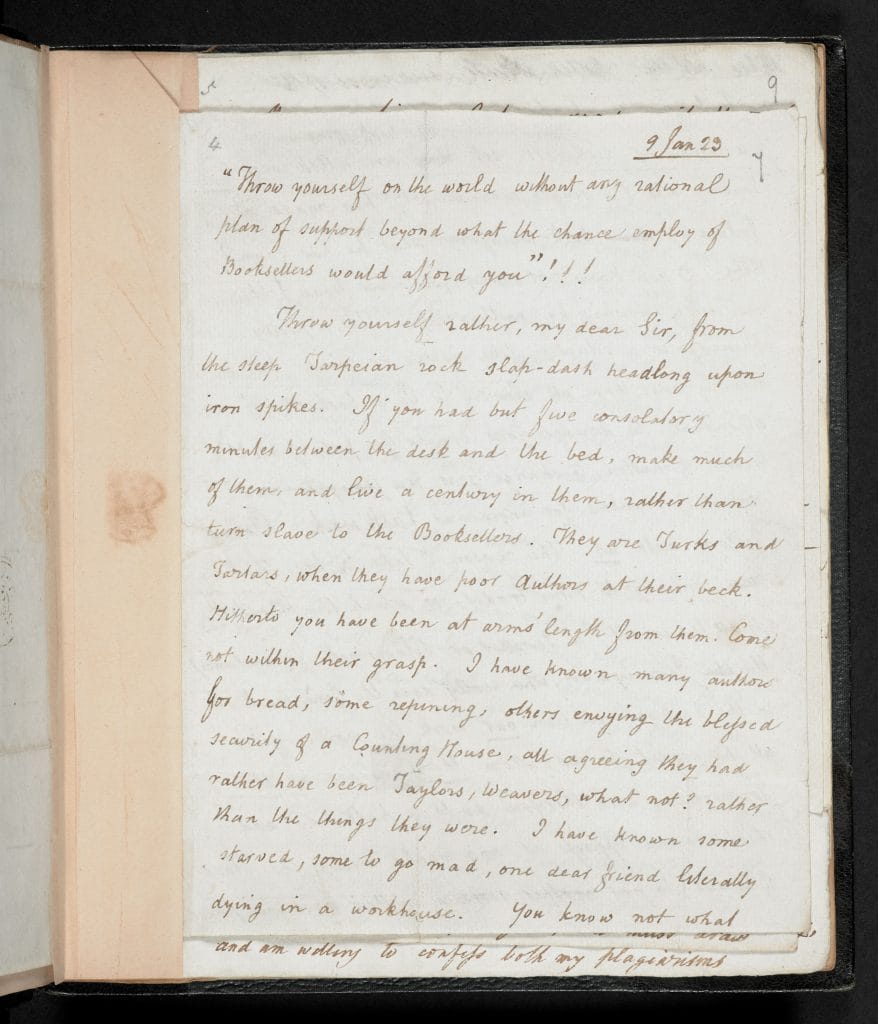

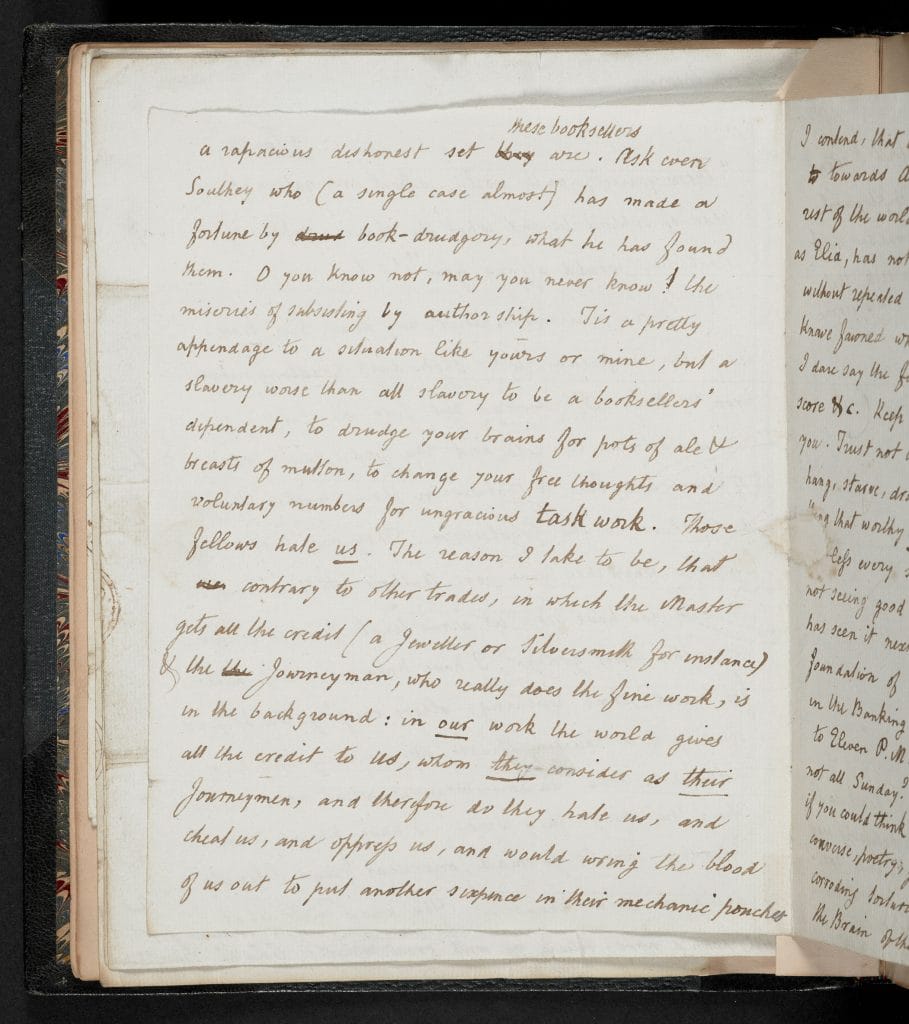

Brother and sister lived together for the rest of their lives in what Charles later described as ‘double singleness’. Charles continued dutifully working in the accountancy department of the East India Company, writing essays and poetry in the evening, while Mary kept the household and – despite her lack of education – taught herself French, Latin and Italian. Their work together on the book that became known as Tales from Shakespeare helped Mary begin a new career as a children’s author, and was followed by two more works written for young readers, both collaborations. While Charles developed a reputation as a well-connected critic and essayist, Mary only ever published one independent work for adults, an essay on needlework written under a pseudonym. Much of her work – as well as her role in Tales from Shakespeare – was neglected until long after she died in 1845, 13 years after Charles.

Making the Tales

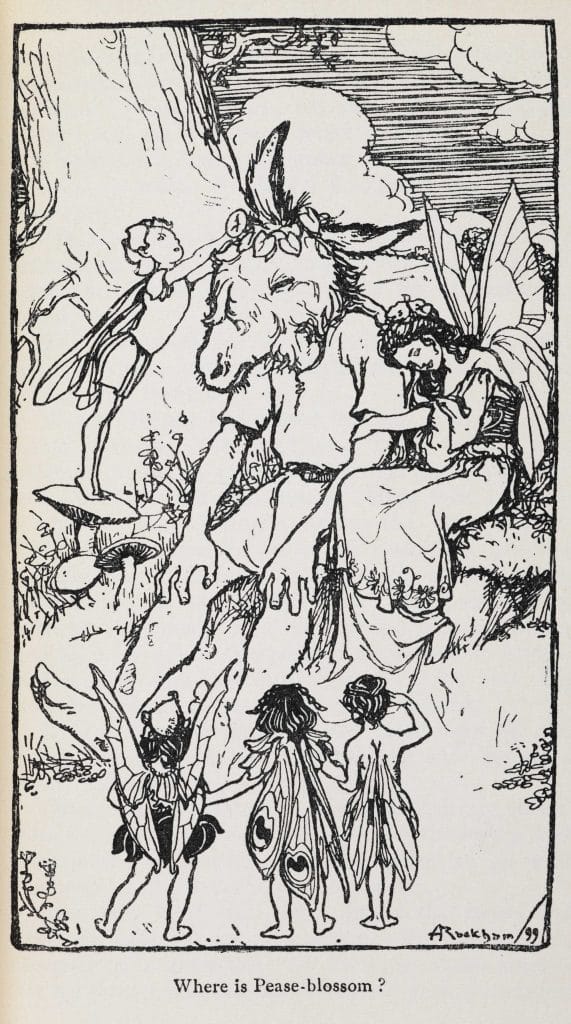

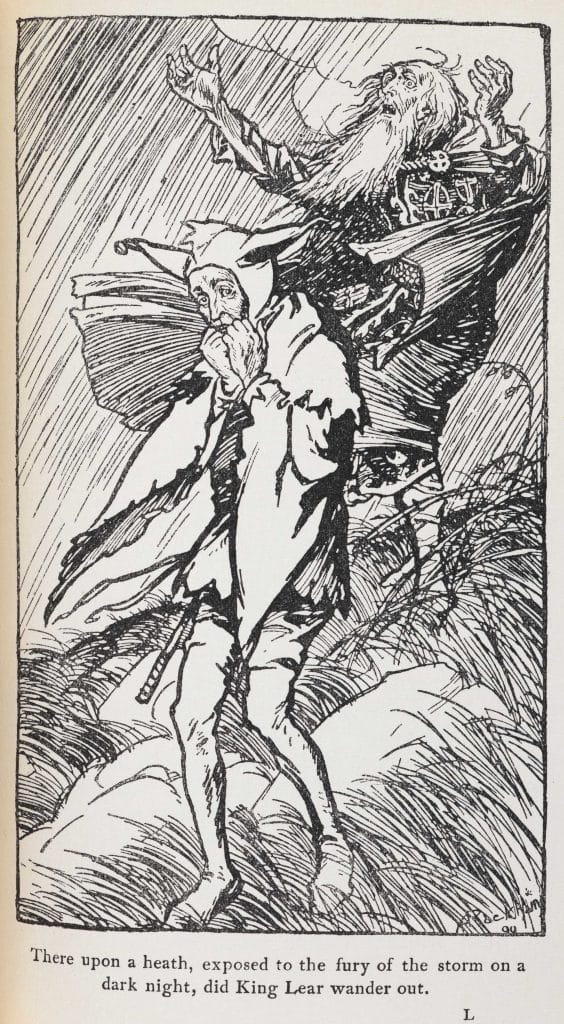

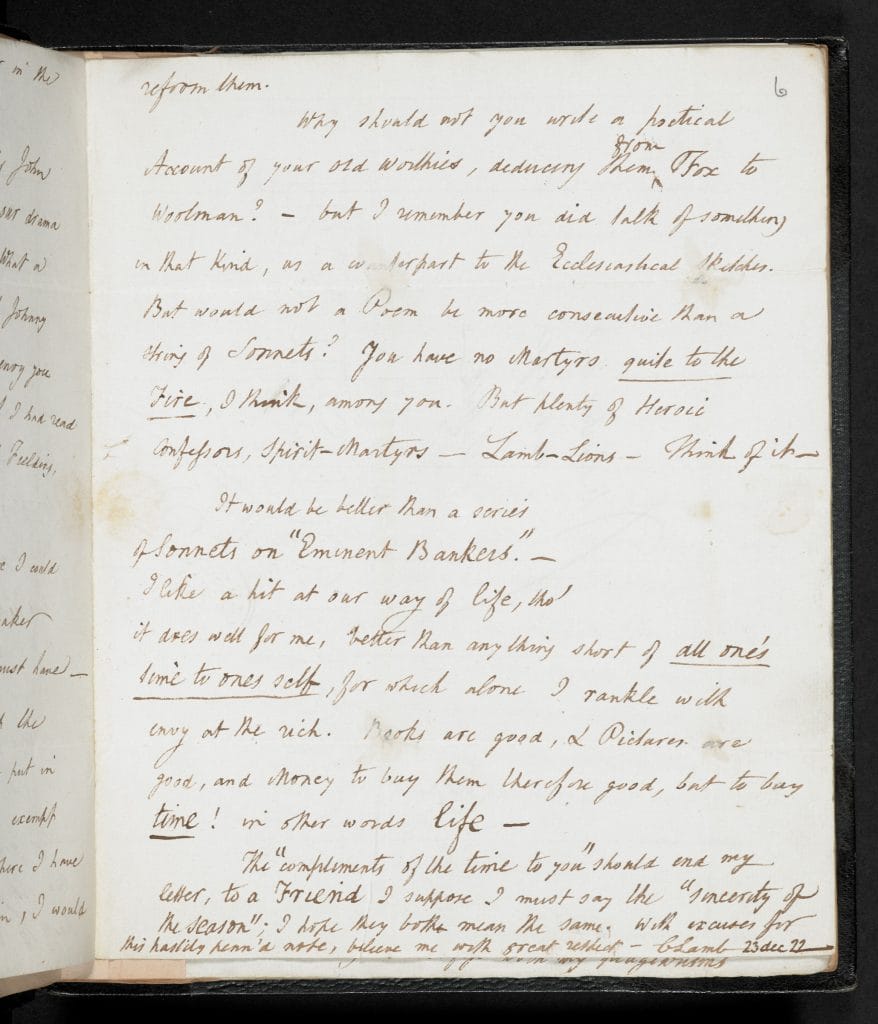

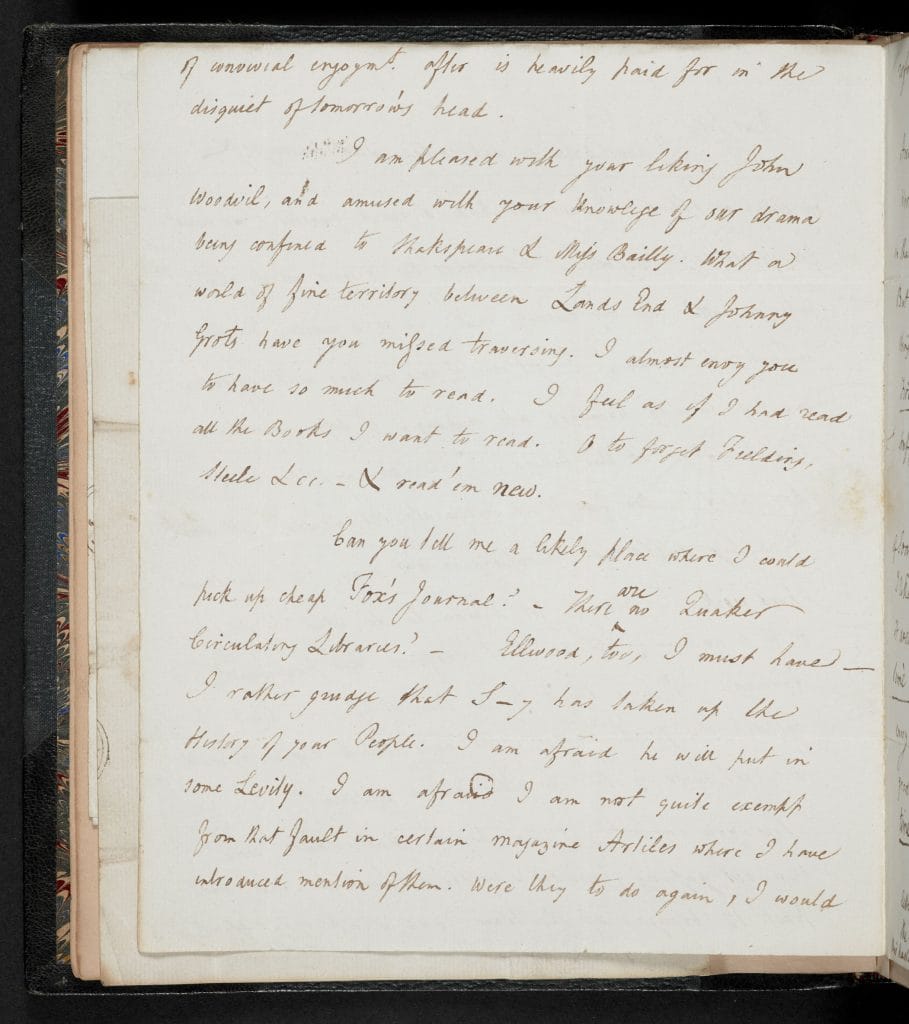

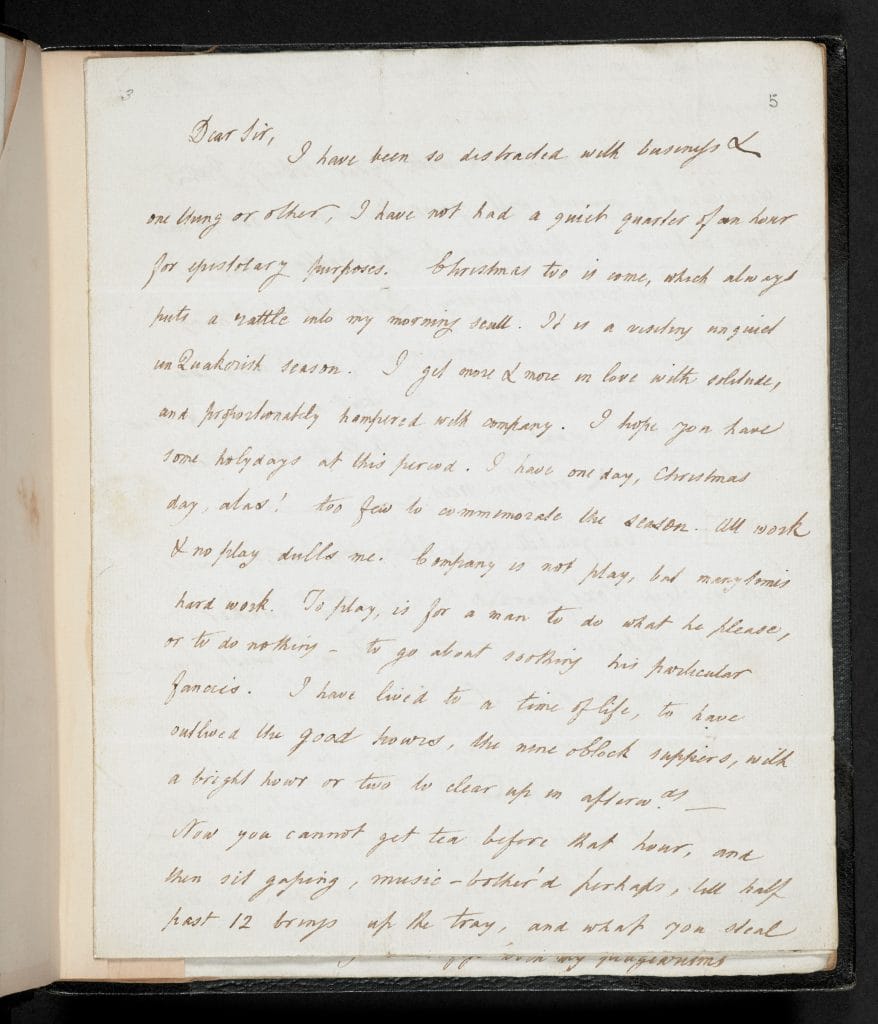

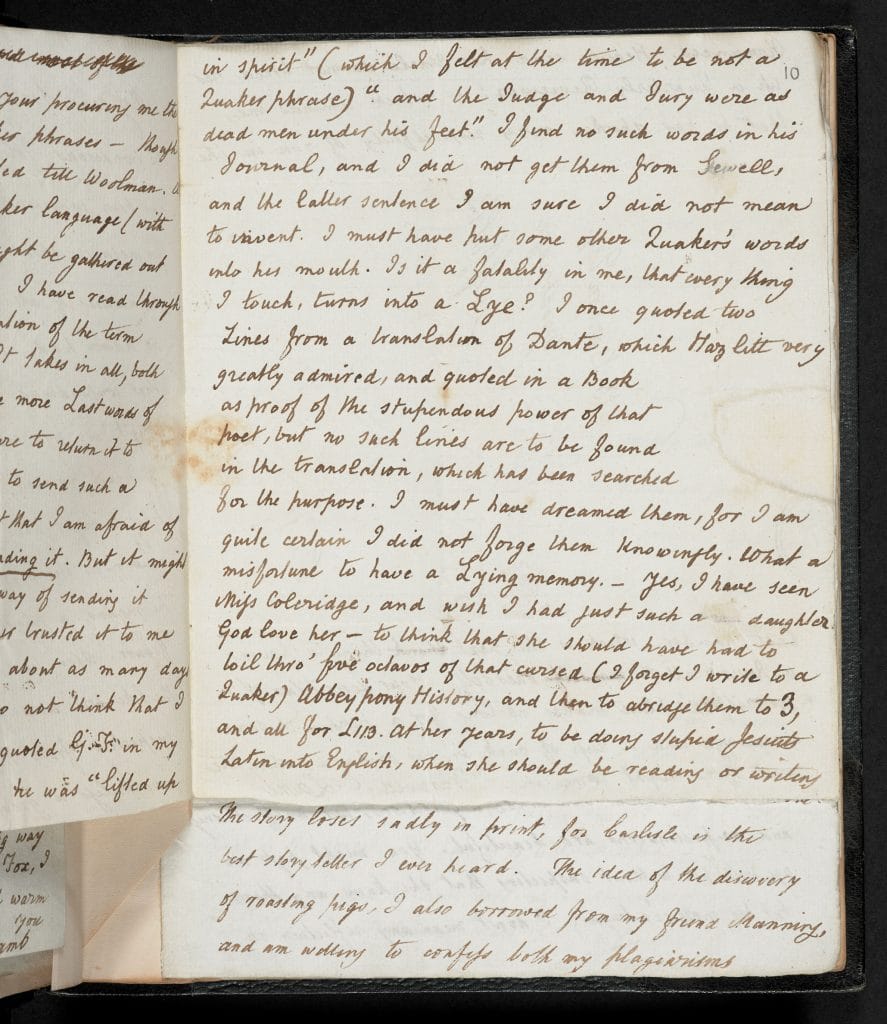

In 1805, the publisher Mary Jane Godwin, second wife of the radical philosopher William Godwin, approached Mary Lamb with the idea of adapting Shakespeare’s plays into prose narratives for children. Mary agreed, and encouraged Charles to get involved too; she tackled the comedies, while he worked on the tragedies, each editing the other’s work. Cleverly distilling the story of each play into a short, readable narrative that could be understood by children – particularly girls, who were less likely to be given access to books during this period – they nevertheless aimed to preserve as much of Shakespeare’s own language as possible, while also filtering out material they considered unsuitable for young readers (by modern standards, the Tales are somewhat moralising and didactic). A letter by Mary offers a charming account of the brother and sister team at work, seated at the same table: ‘like Hermia & Helena in the Midsummer Night’s Dream … I taking snuff & he groaning all the while & saying he can make nothing out of it, which he always says till he has finished’.

In the end, the Lambs produced versions of 20 plays, including some of the most famous in the canon – The Tempest, King Lear, Hamlet, Othello, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Taming of the Shrew and The Merchant of Venice among them. Mary was responsible for some 14 plays in all, chiefly comedies, with Charles having done six tragedies. But when the book was published in 1807 as Tales from Shakespeare, Designed for the Use of Young Persons, Charles was credited as the sole author, not merely because of his sister’s gender but because of the stigma surrounding her mental illness. Only after 1838, when her name was finally added to the book’s title page, has Mary been acknowledged for the decisive role she played in creating one of the most loved children’s books of the last two centuries.

Friends and contemporaries

Charles became close to Samuel Taylor Coleridge at school, and the friendship was one of the most important in his life: Lamb’s early poetry was published alongside his older friend’s in the second edition of Coleridge’s Poems, and it was via Coleridge that he became intimate with other leading lights of the English romantic literary movement. He became close friends with William and Dorothy Wordsworth, as well as with the William Godwin family (the connection, of course, to Tales from Shakespeare).

From 1806, Charles and Mary began hosting weekly soirees at their home in London, and became the centre of a vibrant and remarkable social circle that included many of the most exciting writers in London – the poets John Keats, the essayists William Hazlitt and Thomas de Quincey, and the critic and journalist Leigh Hunt (another schoolfriend of Lamb’s), many of whom remembered both Charles and Mary fondly. One recollection by the painter Benjamin Robert Haydon concerns a boisterous and drunken dinner in December 1817 at which Lamb, Wordsworth and Keats were all present – an indication, apart from anything else, how tightly knit the London literary community was during this time. According to Haydon’s recollections of this ‘immortal dinner’, ‘Wordsworth’s fine intonation as he quoted Milton and Virgil, Keats’ eager, inspired look, Lamb’s faint sparkle of lambent humour, so speeded the stream of conversation, that in my life I never passed a more delightful time.’

Lambs’ Tales globally

Although reviews were lukewarm, Tales from Shakespeare was a commercial success and went through numerous editions before the end of the nineteenth century, growing more and more popular as time went on. With over 200 separate English editions having been produced since 1807, the book has never been out of print since it was published, and has become arguably the most read adaptation of Shakespeare ever produced.

And not just in the English-speaking world: it is largely because of the Lambs’ efforts that Shakespeare’s work has become known in countries all across the globe, particularly in Asia. The Tales were read and taught in schools in India and Malaysia, especially during British colonial rule, and copies also made their way to Japan, where they were first translated in the 1870s. By the 1950s, there were nearly a hundred separate versions of the Tales in Japanese alone, and altogether over 40 translations have been produced in languages as diverse as Burmese, Swahili, Macedonian, Hungarian and Swahili. Their brevity and relatively simple language – much easier to translate than a full play – aided this extraordinary popularity among readers of all ages.

In China, Tales from Shakespeare became a genuine sensation. In 1903, ten of the stories were translated by an anonymous writer into classical Chinese under the alluring title Xiewai qitan (‘Strange Tales from Overseas’). As the preface put it:

[Shakespeare’s] plays and stories became fashionable in England for a time and have been rendered into French, German, Russian, Italian and read by people all over the world. Nowadays Shakespeare is recognised and praised by the Chinese academic circle.

In an attempt to catch the eye of book-buyers (presumably men), each of the tales was given a sensationalistic title: ‘Proteus Sells Out his Close Friend for Lust’ for The Two Gentlemen of Verona, ‘Playing Tricks, the Devoted Wife Steals the Ring’ for All’s Well That Ends Well.

So successful was this first collection that, the following year, a translation team led by the prolific translator Lin Shu (who famously couldn’t understand English) made another attempt on Tales from Shakespeare, this time rendering all 20 stories into Chinese under the title Yinguuo shiren yinbian (‘An English Poet Reciting from Afar on Joyous Occasions’). This edition sold so well that it was reprinted 11 times in the next three decades, and inspired Lin and his team to follow it with another batch of tales in 1916, the 300th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death – this time based on the remaining plays that the Lambs had neglected to include.

It is an irony the Lambs might have enjoyed that, had their adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays not existed, the ‘English Poet’ might never have become the world-famous figure he now is.

Written by:Andrew Dickson

The text in this article is available under the (Creative Commons License).