Virginia Woolf’s London

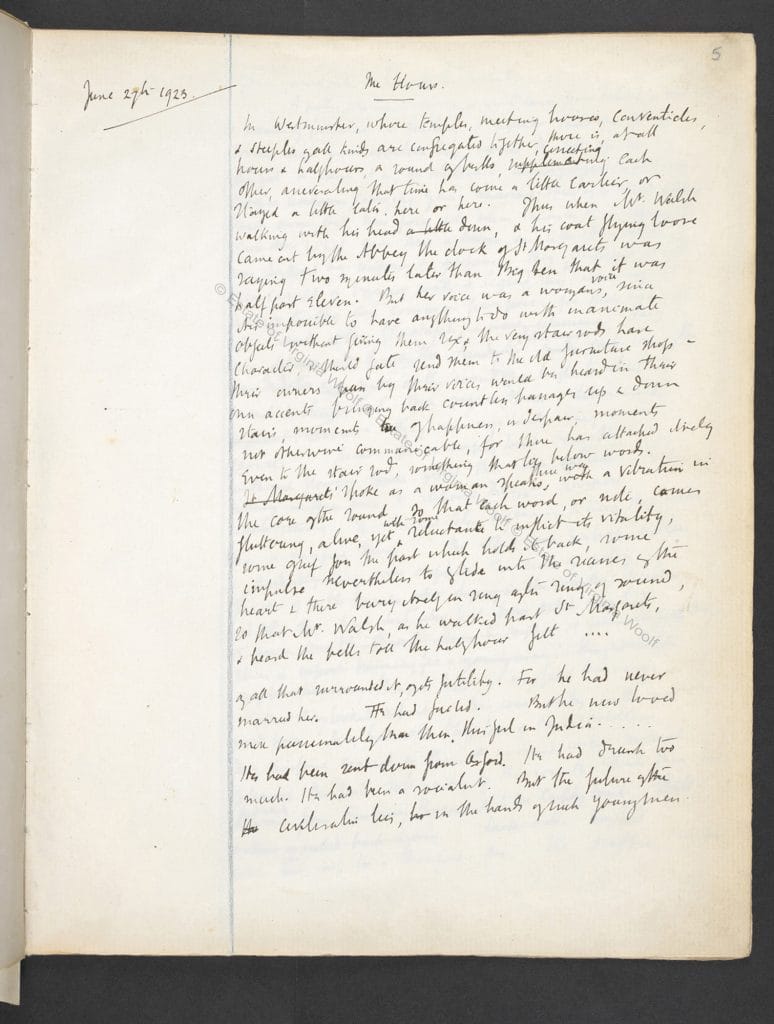

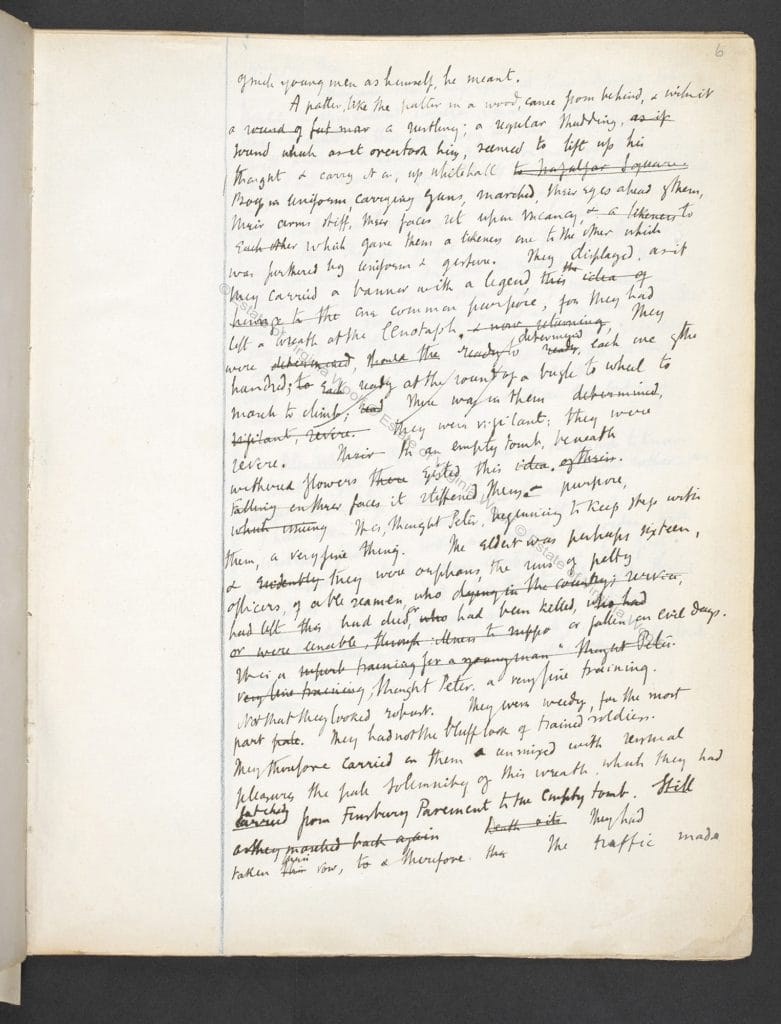

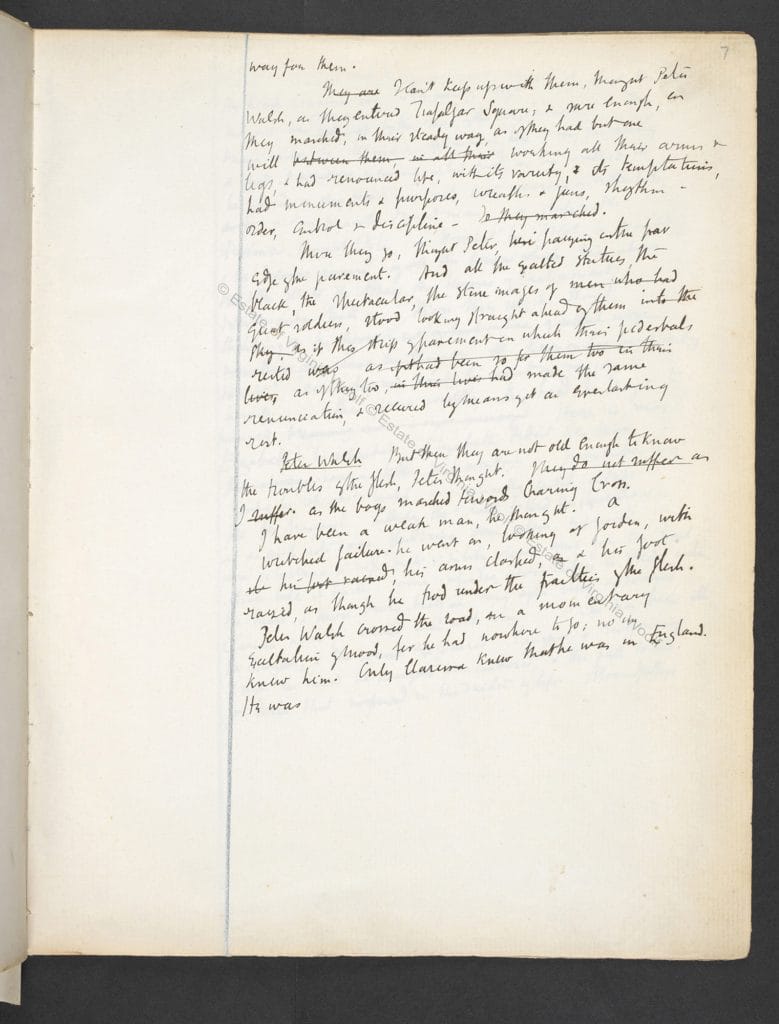

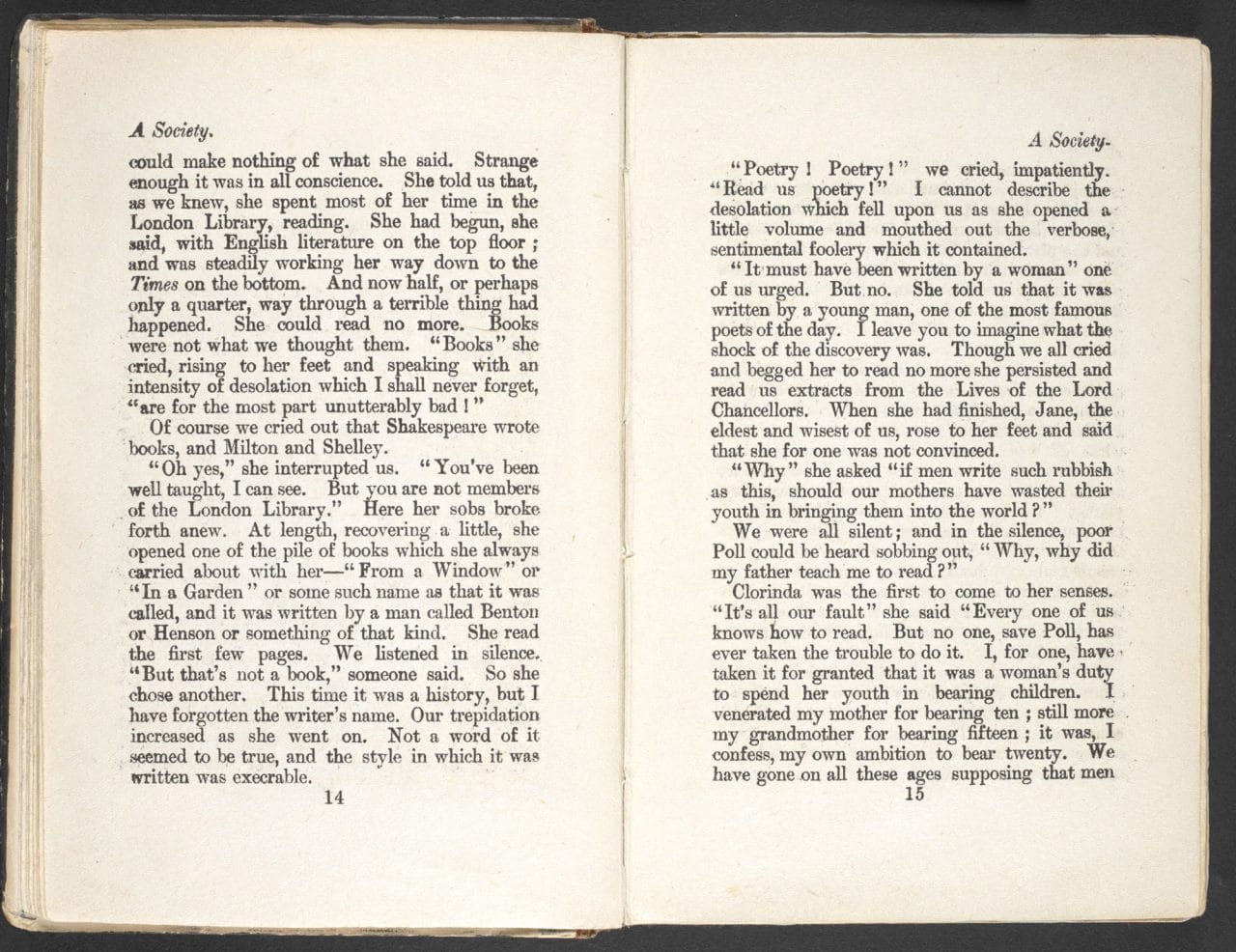

Virginia Woolf loved London, and her novel Mrs Dalloway famously begins with Clarissa Dalloway walking through the city. David Bradshaw investigates how the excitement, beauty and inequalities of London influenced Woolf’s writing.

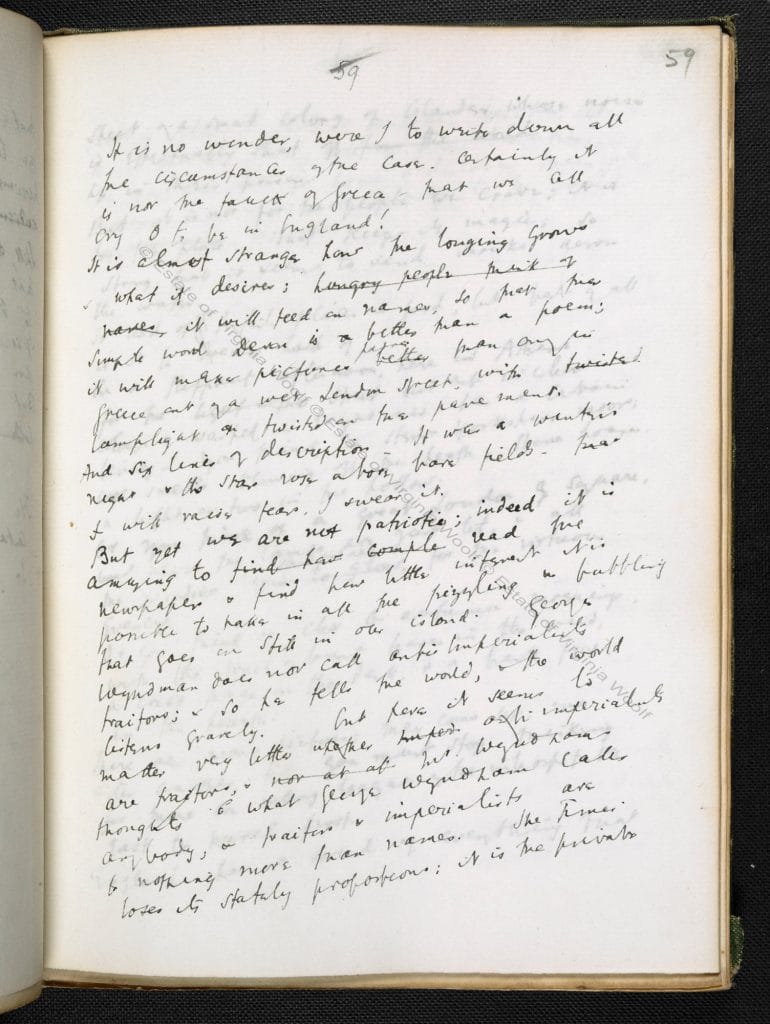

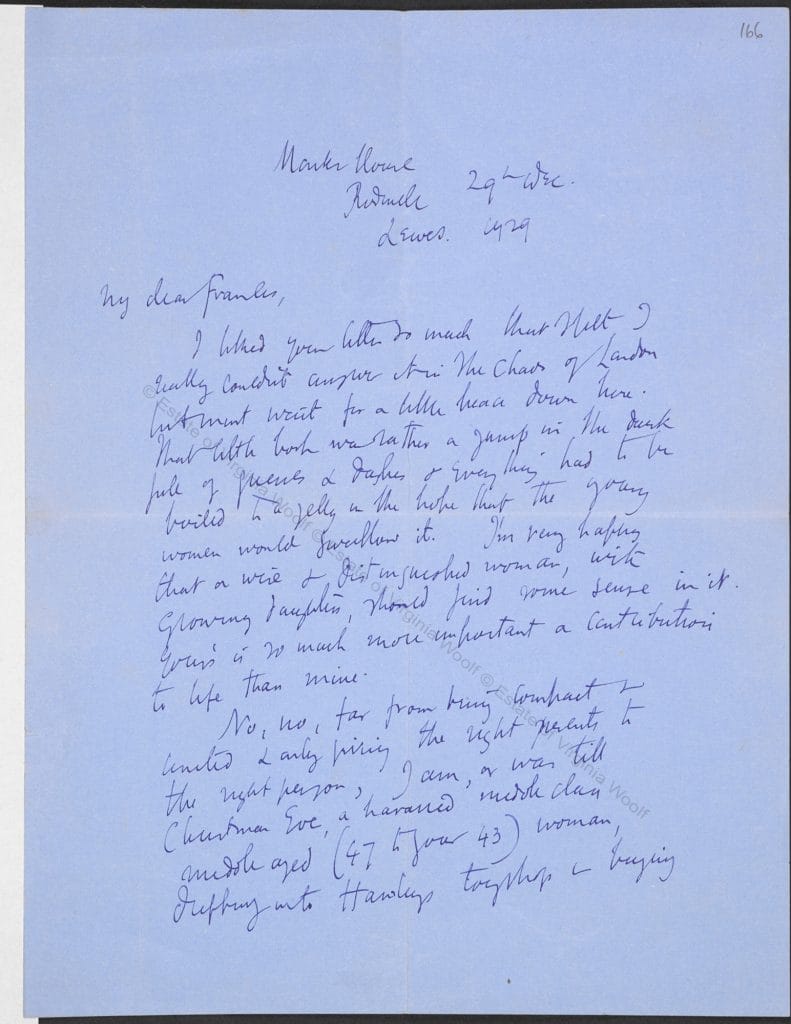

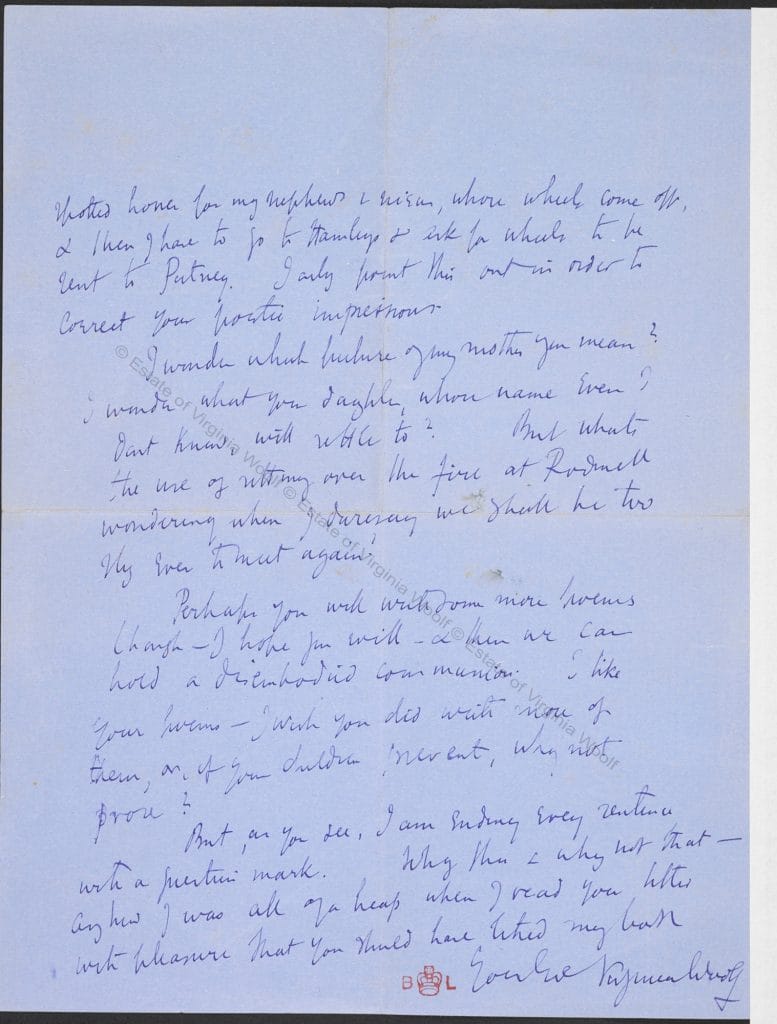

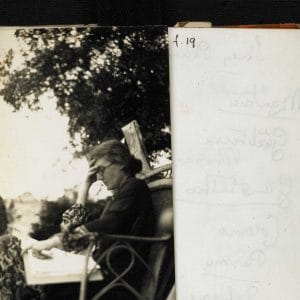

If Cornwall captured Woolf’s soul, London bagged her heart. Writing to a cousin from Hampshire on 18 August 1898, she confessed that she was ‘counting the weeks till the 22nd September when we return to our beloved city’.[1] Her love affair with London, and especially the City of London, would never cool, and when parts of it were reduced to rubble during the Blitz of 1940–41 she lamented its devastation like a grief-stricken widow.

‘The geniality, sisterhood, motherhood, brotherhood of this uproar’

London, indeed, was nothing less than Woolf’s imaginative lifeblood. Visiting its landmarks, parks and gardens was one of her favourite diversions, and she was arguably at her happiest when swept up by its clamorous, teeming thoroughfares. ‘Personally,’ she wrote in a 1916 review of a book about London, ‘we should be willing to read one volume about every street in the city, and should still ask for more. From the bones of extinct monsters and the coins of Roman emperors in the cellars to the name of the shopman over the door, the whole story is fascinating and the material endless’.[2] This entrancement with London was epitomised in her never dipping delight in the raucous brouhaha of the Strand and Oxford Street – ‘What shall I think of that[s] liberating & refreshing?’ Woolf wrote in her diary on 29 March 1940. ‘… The river. Say the Thames at London bridge; & buying a notebook; & then walking along the Strand & letting each face give me a buffet’. [3]

This invigorating ‘buffet’ is also experienced by a number of her characters. We read in the ‘1891’ chapter of The Years (1937), for example, that:

The uproar, the confusion, the space of the Strand came upon [Eleanor Pargiter] with the shock of relief. She felt herself expand … a turmoil of variegated life came racing towards her. It was as if something had broken loose – in her, in the world. [4]

Similarly, when the patrician Elizabeth Dalloway travels to the Strand she feels a colossal sense of release from her class-bound and gendered destiny, and a potent sense of what her future might hold:

It was quite different here from Westminster, she thought, getting off at Chancery Lane. It was so serious; it was so busy. In short, she would like to have a profession. She would become a doctor, a farmer, possibly go into Parliament if she found it necessary, all because of the Strand. [5]

Elizabeth looks about her and feels the uplifting press of:

people busy about their activities, hands putting stone to stone, minds eternally occupied not with trivial chatterings … but with thoughts of ships, of business, of law, of administration and with it all so stately (she was in the Temple), gay (there was the river), pious (there was the Church) (p. 116).

She walks up Fleet Street towards St Paul’s noting the ‘queer alleys, tempting by-streets’ on either side of her, and conscious of her daring as ‘a pioneer, a stray, venturing, trusting’ (p. 117) beyond her normal environment. Nearer to St Paul’s she becomes even more intensely aware that she is being transported by ‘the geniality, sisterhood, motherhood, brotherhood of this uproar’ (p. 117), before a restraining sense of duty kicks in and she returns to Westminster to prepare for her mother’s party. During the Second World War, a distraught Woolf walked through the same bombed district. ‘And then, the passion of my life, that is the City of London – to see London all blasted, that too raked my heart. Have you that feeling for certain alleys and little courts, between Chancery Lane and the City?’ she asked her friend Ethel Smyth. ‘I walked to the Tower the other day by way of caressing my love of all that’.[6]

Elizabeth Dalloway’s response to the London streets may seem of a piece with her mother’s rapture as she walks from Westminster to Bond Street to buy flowers for her party. As she ventures forth, Clarissa Dalloway merges blissfully with:

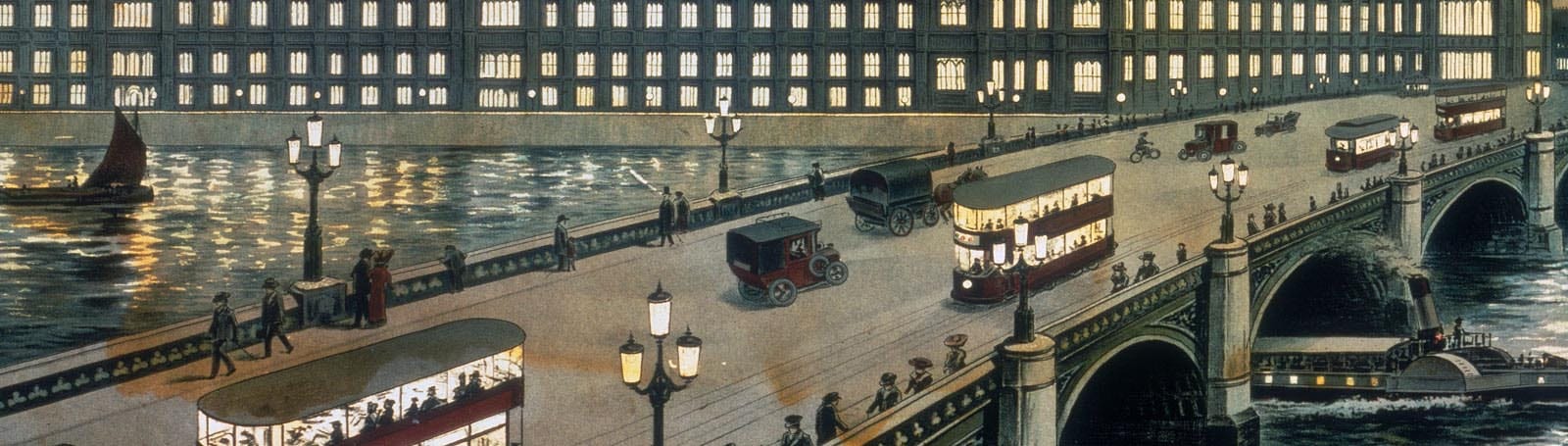

the swing, tramp, and trudge; in the bellow and the uproar; the carriages, motor cars, omnibuses, vans, sandwich men shuffling and swinging; brass bands, barrel organs; in the triumph and the jingle and the strange high singing of some aeroplane overhead was what she loved; life; London; this moment of June (p. 4).

As I have cautioned elsewhere, however, Clarissa’s celebrated journey from one of London’s most exclusive residential areas via a Royal Park (St James’s) to its premier shopping street can also be viewed less favourably. ‘Mrs Dalloway’s walk’, I have suggested, ‘so often prized by readers for the alfresco city pleasures it brings to her mind, her elated response to the ‘divine vitality’ (p. 6)of London’s street-life, may be seen, from a different angle, as a token of her gilded confinement.’[7]

Significantly, once she is in Bond Street she is ‘not even Clarissa any more’ but more formally and restrictively, ‘Mrs Richard Dalloway’ (p. 9).

City of inequalities and contradictions

For as well as being an ‘enchanting … tawny coloured magic carpet’,[8]

Woolf also recognised that London’s cityscape embodied the patriarchal repression of women, and in addition to rejoicing in the city’s freedoms she was also critical of its myriad limitations. Addressing the influential men who held sway in London’s most privileged spaces, for example, she writes in Three Guineas (1938):

Your world then, the world of professional, public life … is enormously impressive. Within quite a small space are crowded together St Paul’s, the Bank of England, the Mansion House, the massive if funereal battlements of the Law Courts; and on the other side, Westminster Abbey and the Houses of Parliament. There, we say to ourselves … our fathers and brothers have spent their lives.[9]

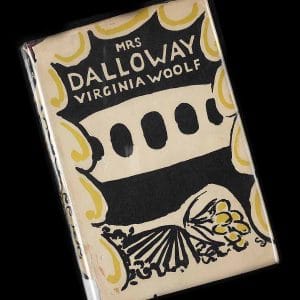

Works such as Jacob’s Room, Flush and The Years in particular engage with the ideological fabric of these monumental buildings, as well as exposing London’s social iniquities and glaring inequalities. Of all her longer works of fiction only To the Lighthouse and Between the Acts are not set in London, and in every one of her other novels we either visit or glimpse some of the more impoverished quarters of the city and witness its homeless, its prostitutes, its tawdriness, its sordidness and its glaring disparities of wealth. Likewise, as Peter Walsh walks up Tottenham Court Road in Mrs Dalloway (1925) he thinks that a speeding ambulance is ‘One of the triumphs of civilization’ (p. 128), painfully unaware that it is almost certainly hurrying towards the impaled corpse of Septimus Warren Smith, a victim of medical backwardness. In short, Woolf’s London is alive with contradictions, and she emphasises this from the very beginning of her career when she describes both the imperial splendour of the Victoria Embankment and the shameful hordes of the destitute it accommodated each night in the opening pages of her first novel, The Voyage Out (1915).[10]

Gardens, parks and the river

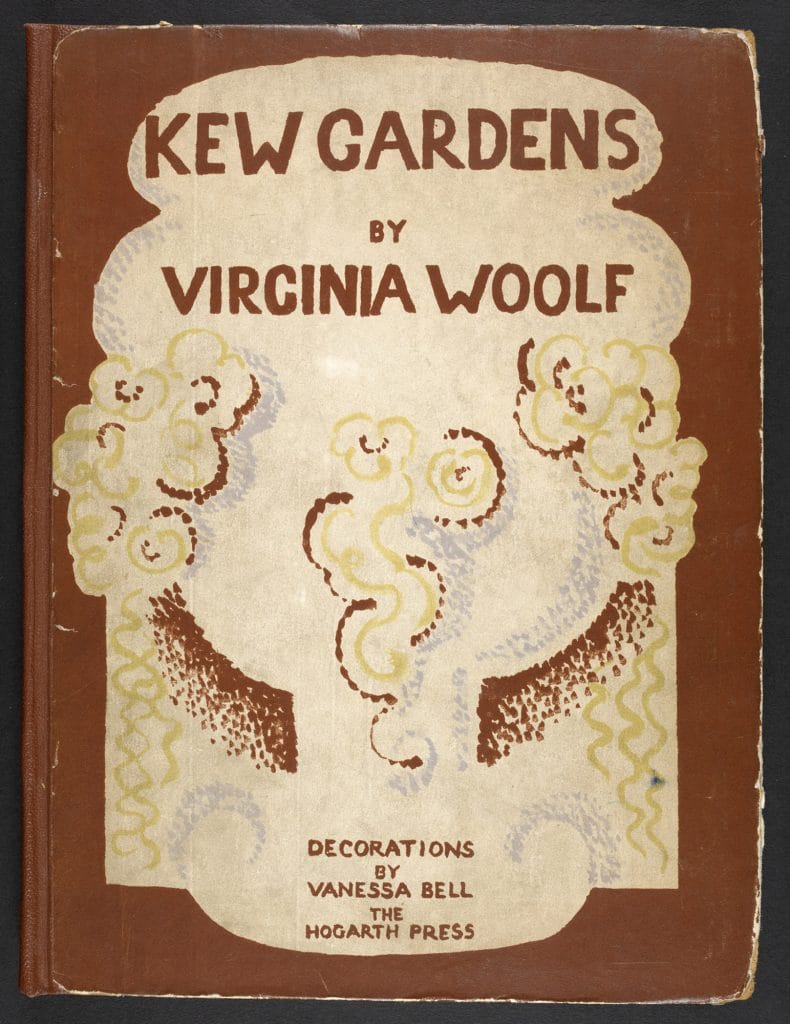

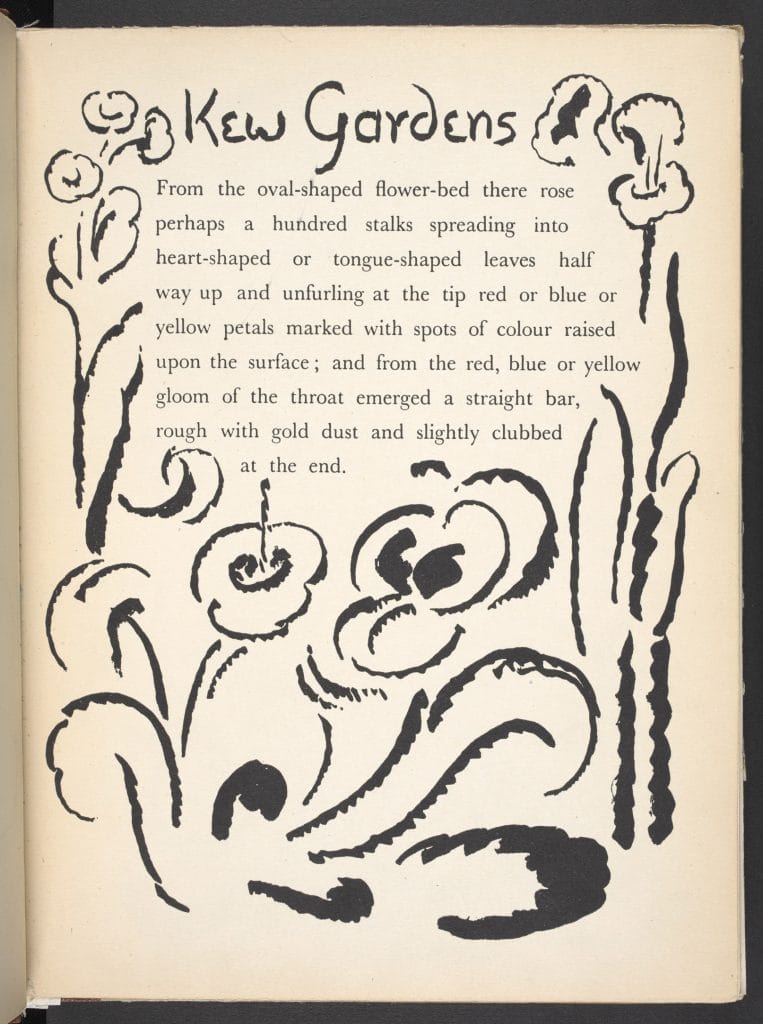

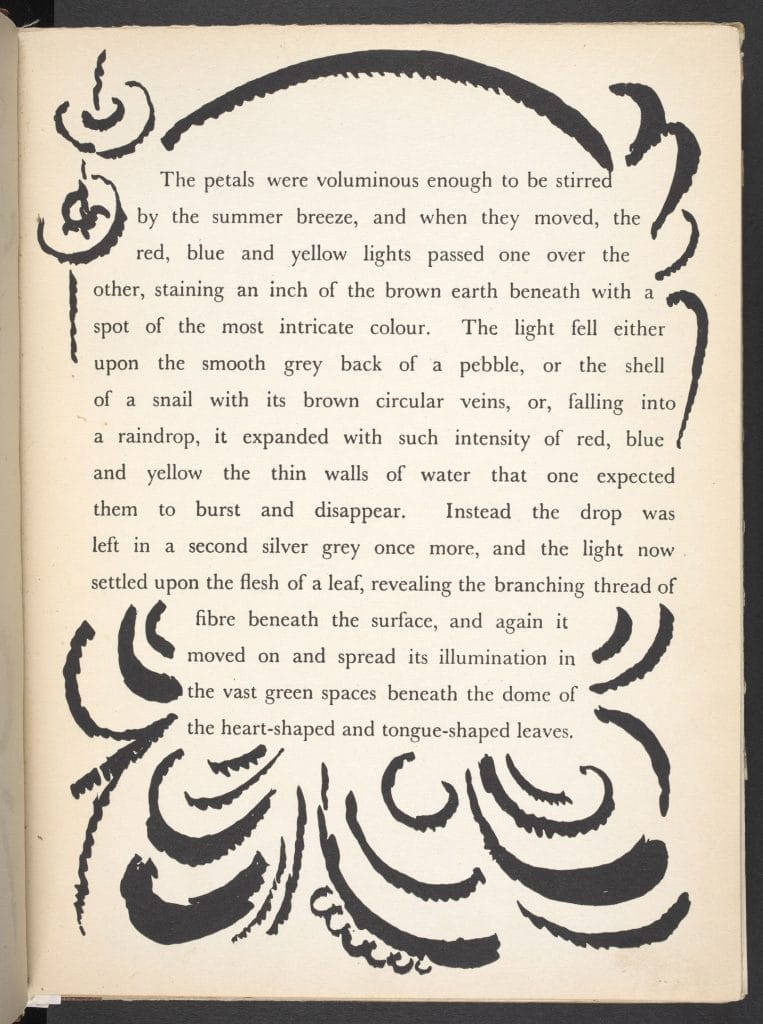

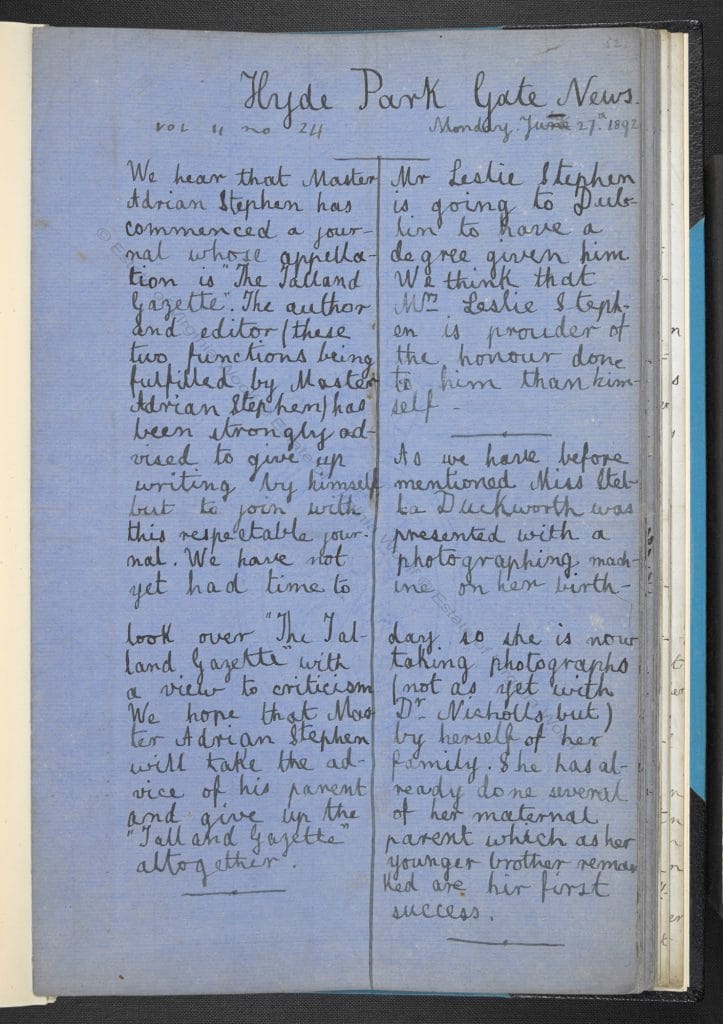

One of Woolf’s most intense London pleasures was visiting its public gardens. She sets an early short story in Kew Gardens, and Katharine Hilbery and Ralph Denham make a sexually charged expedition to its Orchid House in Chapter 25 of Night and Day (1919). As a child, Woolf spent many an hour in Kensington Gardens, often in the company of her father, Leslie Stephen, and these were often difficult occasions. As she notes in her ‘Sketch of the Past’, a poignant late essay published in the posthumous Moments of Being collection, such expeditions were more frequently to be endured rather than enjoyed. But just as it was her habit as an adult to make up fiction as she ambled through London’s parks and gardens, so the young Woolf and her siblings,

to beguile the dullness [of] innumerable winter walks … made up stories, long long stories that were taken up at the same place and added to each in turn … The walks – twice every day in Kensington Gardens – were so monotonous. Speaking for myself, non-being lay thick over those years. [11]

Following the death of their father in 1904, Woolf, her sister Vanessa and her two brothers, Adrian and Thoby, moved from 22 Hyde Park Gate, their family home in Kensington, to the racier environs of 46 Gordon Square, Bloomsbury, and here the green oases of that neighbourhood’s squares – Brunswick, Fitzroy, Tavistock and Gordon – stimulated her imagination and offered daily respite from London’s more pervasive brick, stone, tarmac, concrete and noise.

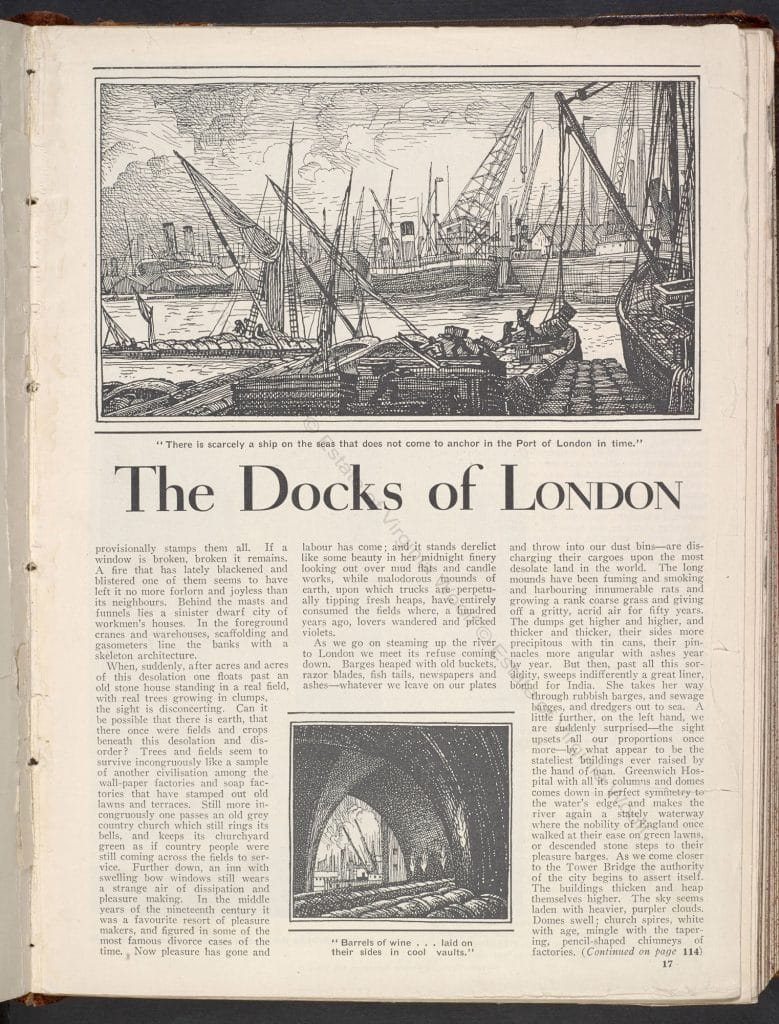

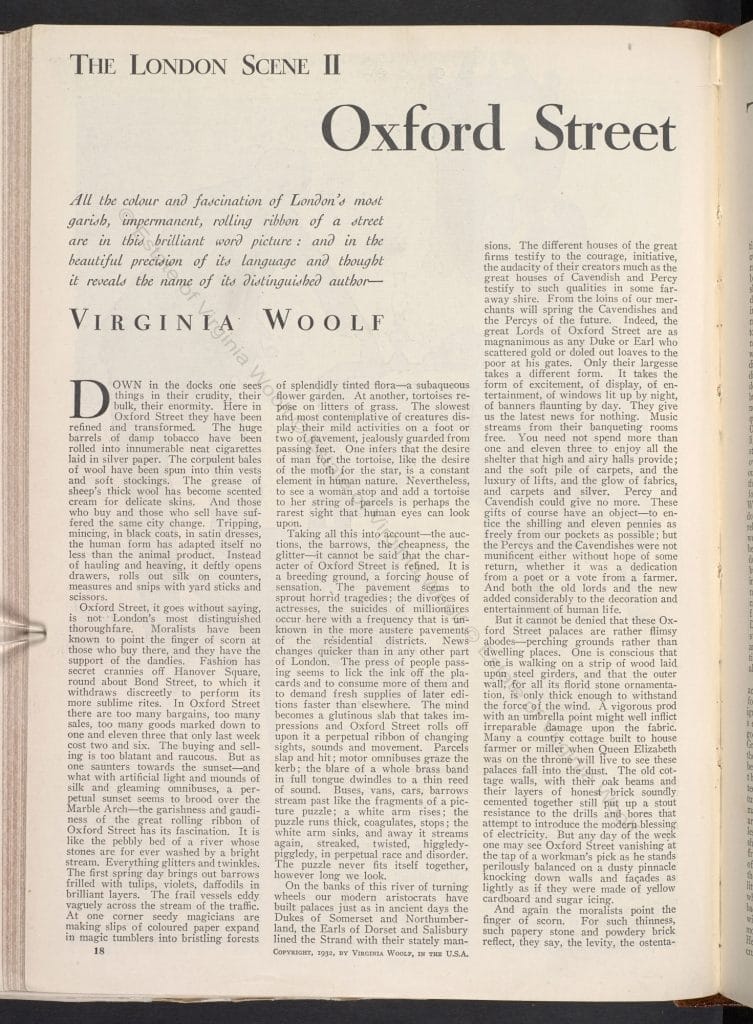

In a similar fashion, London’s spacious parks were also a spur to her fiction. As she put it in a diary entry of 6 June 1935, ‘There is no doubt that the greatest happiness in the world is walking through Regents Park on a green, but wet … evening … & making up phrases’.[12]Furthermore, whether she was travelling upstream to Hampton Court or downstream to Greenwich or the London Docks, the River Thames was another source of constant delight for Woolf. Indeed, the pleasures of the tidal river and the torrential flow of such seething, commercial avenues as Oxford Street and the Strand were almost interchangeable for her. As she puts it in ‘Oxford Street Tide’, ‘the garishness and gaudiness of the great rolling ribbon of Oxford Street has its fascination. It is like the pebbly bed of a river whose stones are forever washed by a bright stream. Everything glitters and twinkles.’[13]

Even though they are vacationing in South America, many of the characters in The Voyage Out cannot stop thinking of London and neither could Woolf. And for all her acknowledgement of its grittier side, it is the invigorating, inclusive commotion of the city on which she most often focusses in her writings. As she puts it so memorably in an essay called ‘Street Haunting: A London Adventure’, ‘As we step out of the house on a fine evening between four and six, we shed the self our friends know us by and become part of that vast republican army of anonymous trampers, whose society is so agreeable after the solitude of one’s own room.’[14]

脚注

- The Flight of the Mind: The Letters of Virginia Woolf, Vol. I, 1888–1912, ed. by Nigel Nicolson assisted by Joanne Trautmann (London: Hogarth Press, 1983), p.19.

- ‘London Revisited’, in The Essays of Virginia Woolf, Vol. II, 1912–1918, ed. by Andrew McNeillie (London: Hogarth Press, 1987), pp. 50–52 (p. 50).

- The Diary of Virginia Woolf, Vol. V, 1936–1941, ed. by Anne Olivier Bell assisted by Andrew McNeillie (London: Hogarth Press, 1984), p. 276.

- Virginia Woolf, Mrs Dalloway, ed. by David Bradshaw (Oxford: Oxford World’s Classics, 2000), p. 116.

- Leave the Letters Till We’re Dead: The Letters of Virginia Woolf, Vol. VI, 1936–1941, ed. by Nigel Nicolson assisted by Joanne Trautmann (London: Hogarth Press, 1980), p. 431.

- David Bradshaw, ‘Woolf’s London, London’s Woolf’, in Virginia Woolf in Context, ed. by Bryony Randall and Jane Goldman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), pp. 229–42 (p. 237).

- The Diary of Virginia Woolf, Vol. II, 1920–1924, ed. by Anne Olivier Bell assisted by Andrew McNeillie (London: Hogarth Press, 1978), p. 301.

- Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own and Three Guineas, ed. by Morag Shiach (Oxford: Oxford World’s Classics, 1992), p. 176.

- See David Bradshaw, ‘“Great Avenues of Civilization”: The Victoria Embankment and Piccadilly Circus Underground Station in the Novels of Virginia Woolf and Chelsea Embankment in Howards End’, in Transits: The Nomadic Geographies of Anglo-American Modernism, ed. by Giovanni Cianci, Caroline Patey and Sara Sullam (Oxford and Bern: Peter Lang, 2010), pp. 189–208.

- Virginia Woolf, ‘Sketch of the Past’, in Moments of Being, ed. by Jeanne Schulkind, rev. by Hermione Lee (London: Pimlico, 2002), pp.78–160 (p. 89).

- The Diary of Virginia Woolf, Vol. IV, 1931–1935, ed. by Anne Olivier Bell assisted by Andrew McNeillie (London: Hogarth Press, 1982), p. 319.

- Virginia Woolf, Selected Essays, ed. by David Bradshaw (Oxford: Oxford World’s Classics, 2008), pp.199–203 (p. 199).

- Virginia Woolf, Selected Essays, pp. 177–87 (p. 177).

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: David Bradshaw

David Bradshaw (1955–2016) was Professor of English Literature at Oxford University and a Fellow of Worcester College. Specialising in late 19th and early 20th century literature, he published on Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, T S Eliot, E M Forster, Aldous Huxley, and Evelyn Waugh, with a particular interest in areas including censorship and obscenity, political and social movements, and the city. Among other modernist texts he has edited Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway, To the Lighthouse and The Waves, co-edited Prudes on the Prowl: Fiction and Obscenity in England, 1850 to the Present Day, and was Co-Investigator of the Complete Works of Evelyn Waugh project at University of Leicester.