Too much suicide?

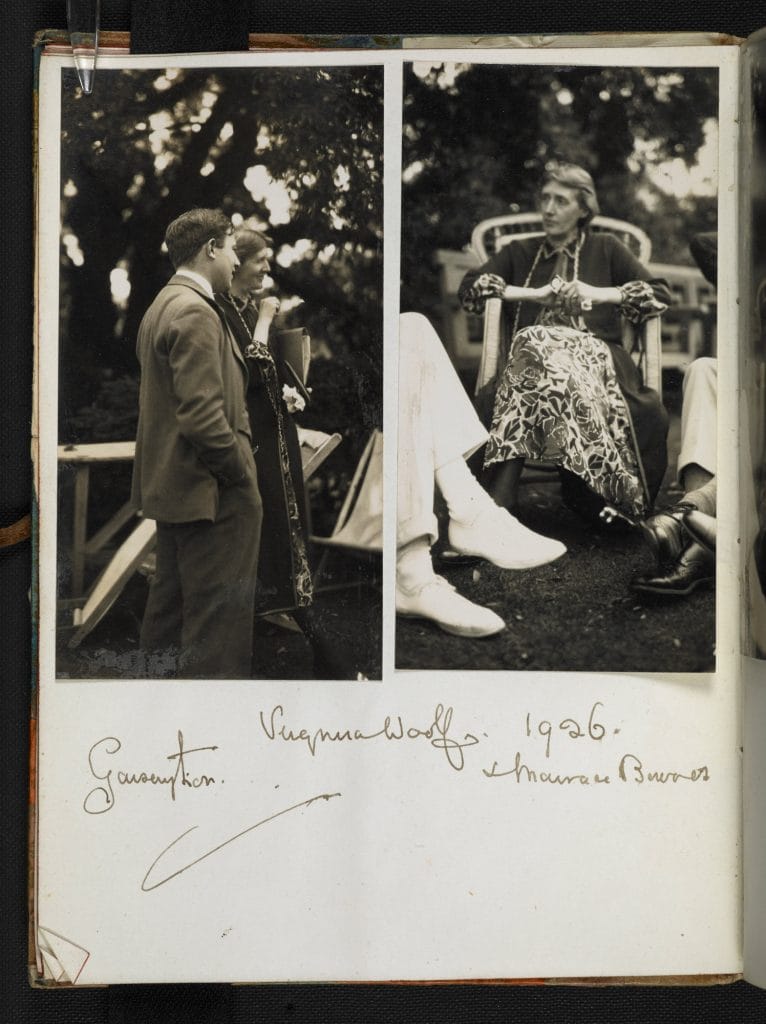

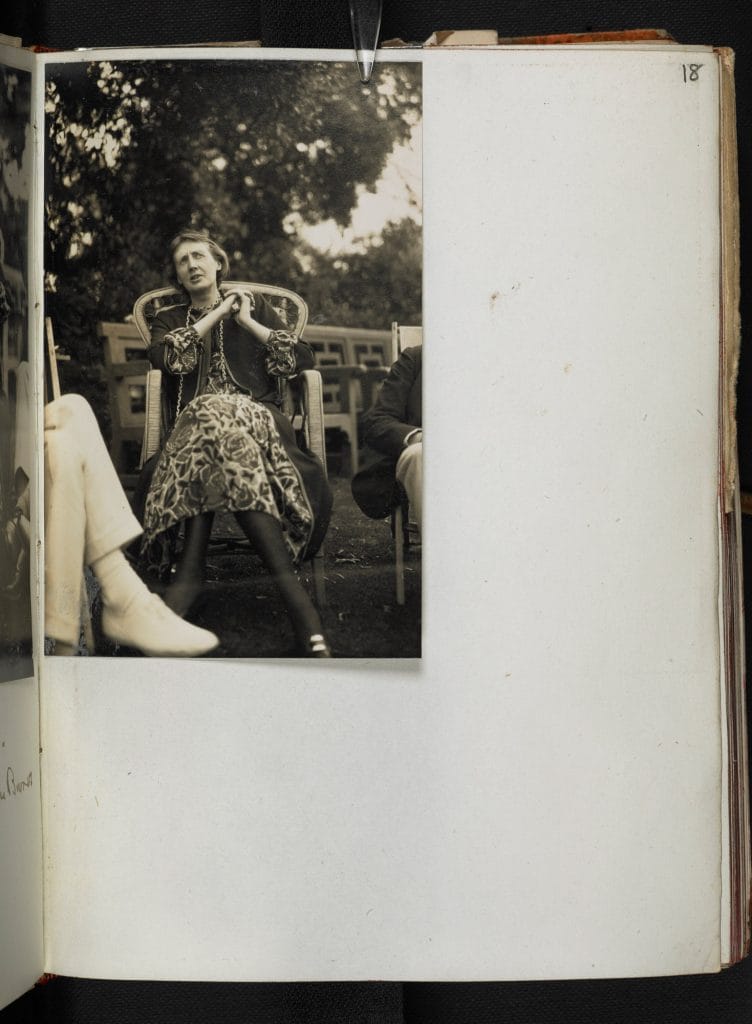

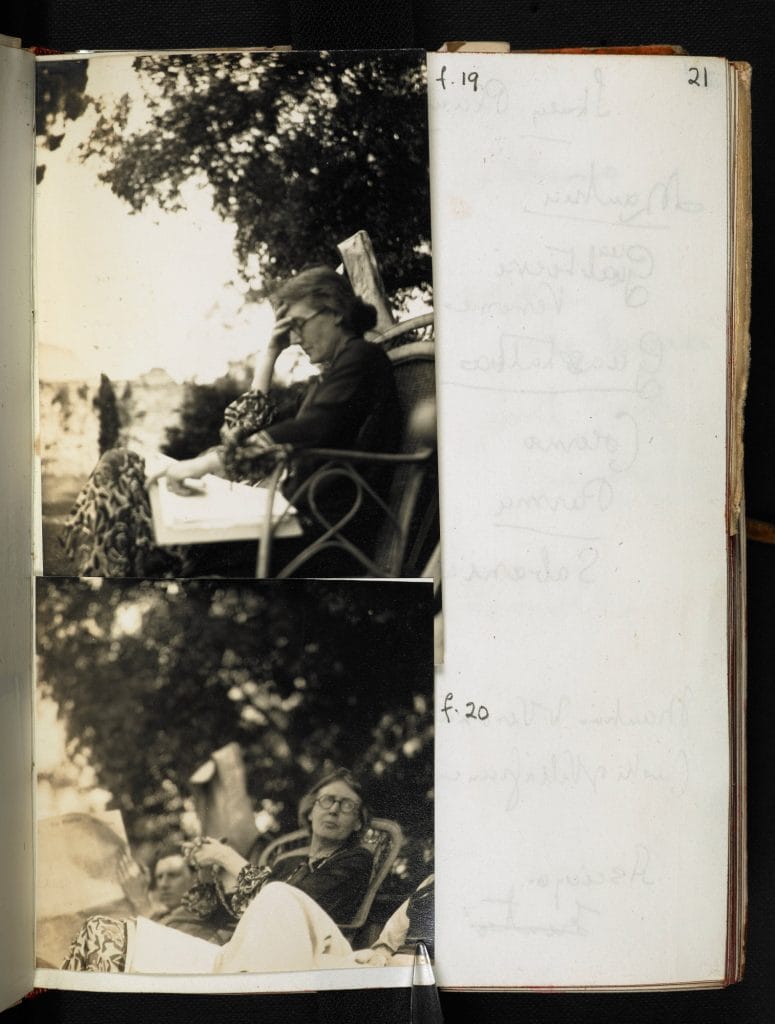

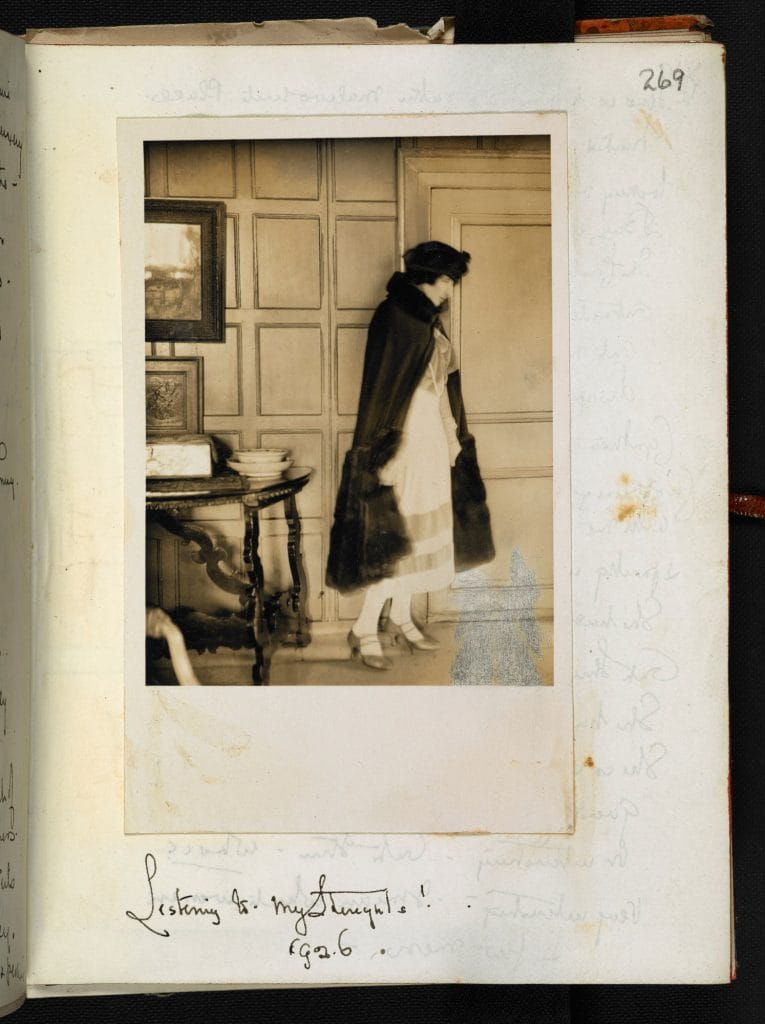

Narratives of Virginia Woolf’s life often place great emphasis on her depression and suicide. Lyndall Gordon considers the way this has overshadowed Woolf’s legacy, and clouded her reputation as a seminal novelist, feminist, and politicized intellectual.

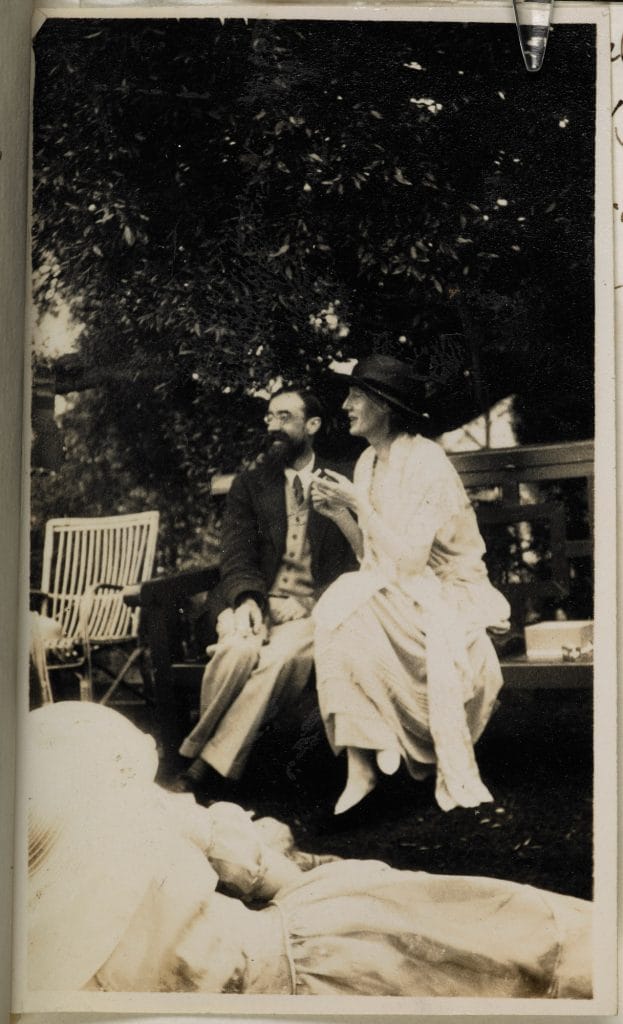

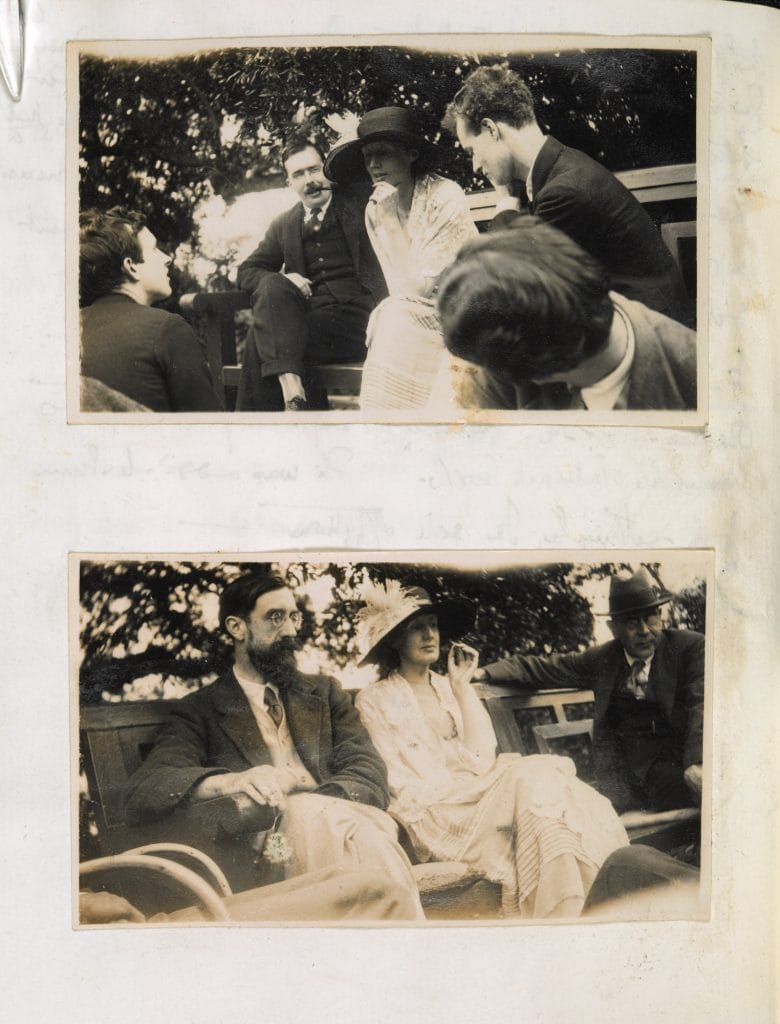

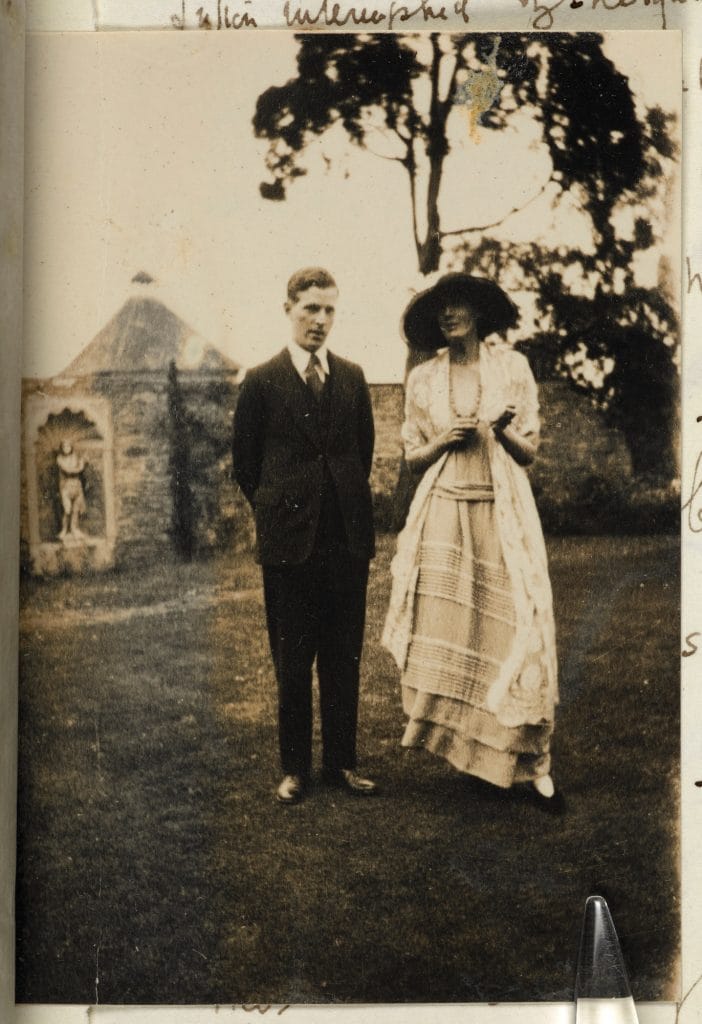

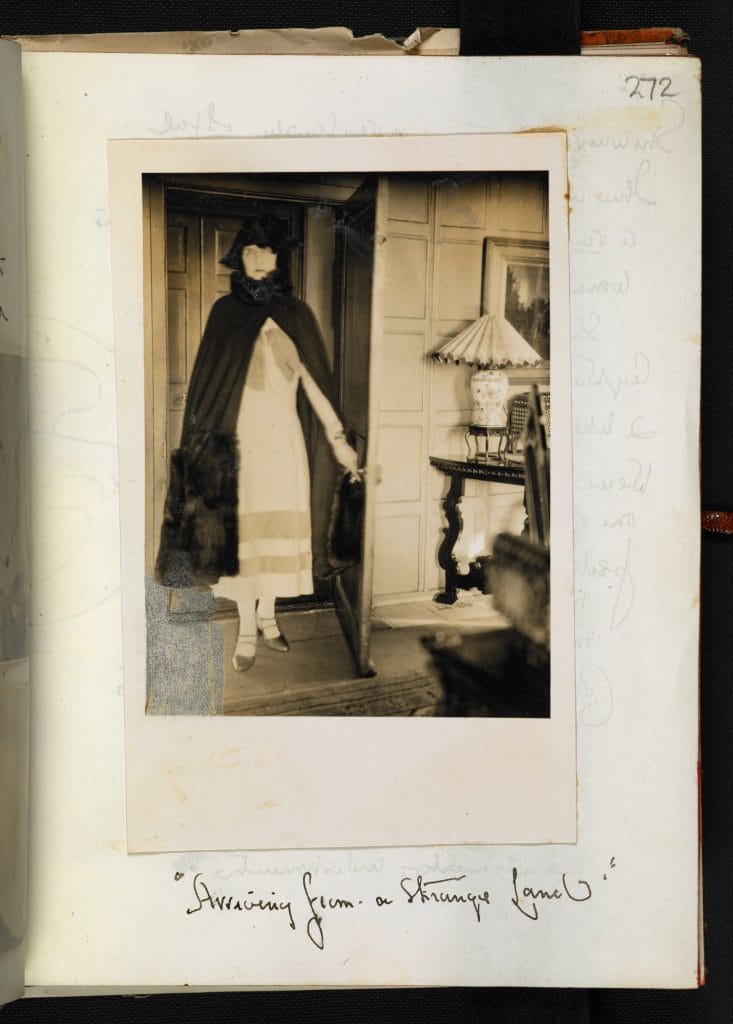

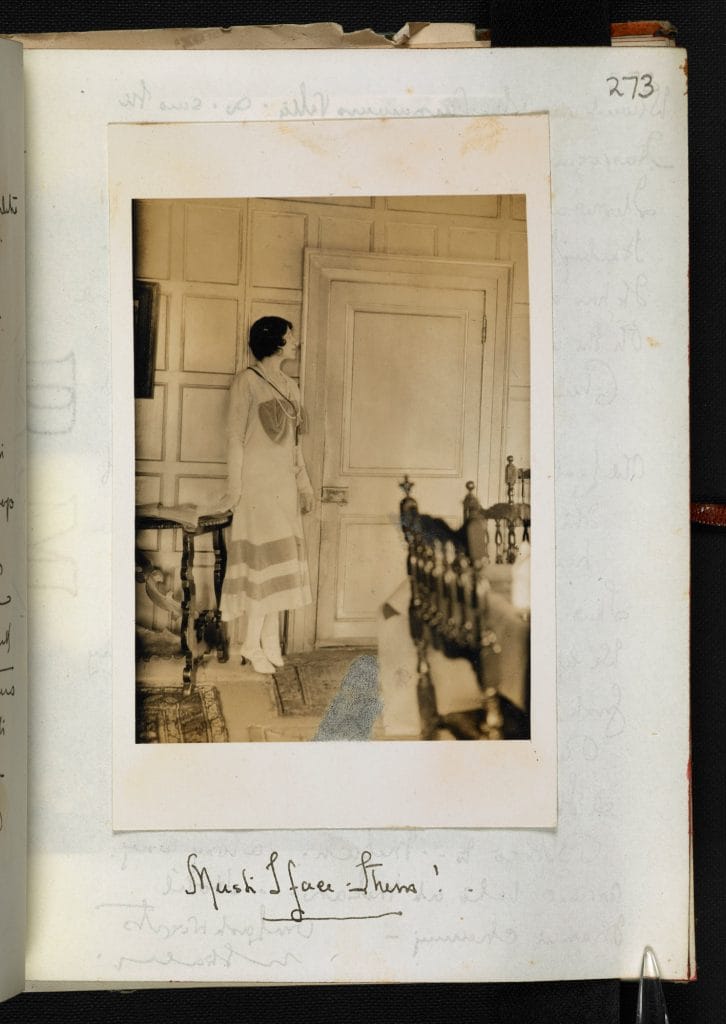

The time has come to question the emphasis on depression and suicide in narratives of Virginia Woolf’s life. Her suicide on 28 March 1941 clouded her reputation as a leading novelist. It suggested to many that she was unstable, reinforced by memories of her as an uninhibited performer at Bloomsbury parties. These performances became linked with what she and her family called ‘madness’ for want of a better word.

Yet the complete editions of her diaries and letters, published in the 1970s and 1980s, revealed a different, more political, more feminist Virginia Woolf, evident, say, in her correspondence with Dame Ethel Smyth. The ex-suffragist and composer (she had composed ‘The March of the Women’ and conducted it with a toothbrush from her window in Holloway Prison) called out the fighter and reformer who came strongly to the fore in the 1930s. Nevertheless, the popular notion of Virginia Woolf as the invalid lady of Bloomsbury, a hothouse plant cut off from the normal world, persists to this day, most visibly in Stephen Daldry’s film The Hours, closely based on a Pulitzer Prize-winning novel of the same name by Michael Cunningham. Fictive scenes include a Virginia Woolf who torments poor Leonard, bickers with him on Richmond station and lies eye to eye with a small dead bird – all belittling images that remove a woman from what she was. Both book and film of The Hours offset a moody, suicide-bent Virginia Woolf against the supposed normality of a sister who shops.

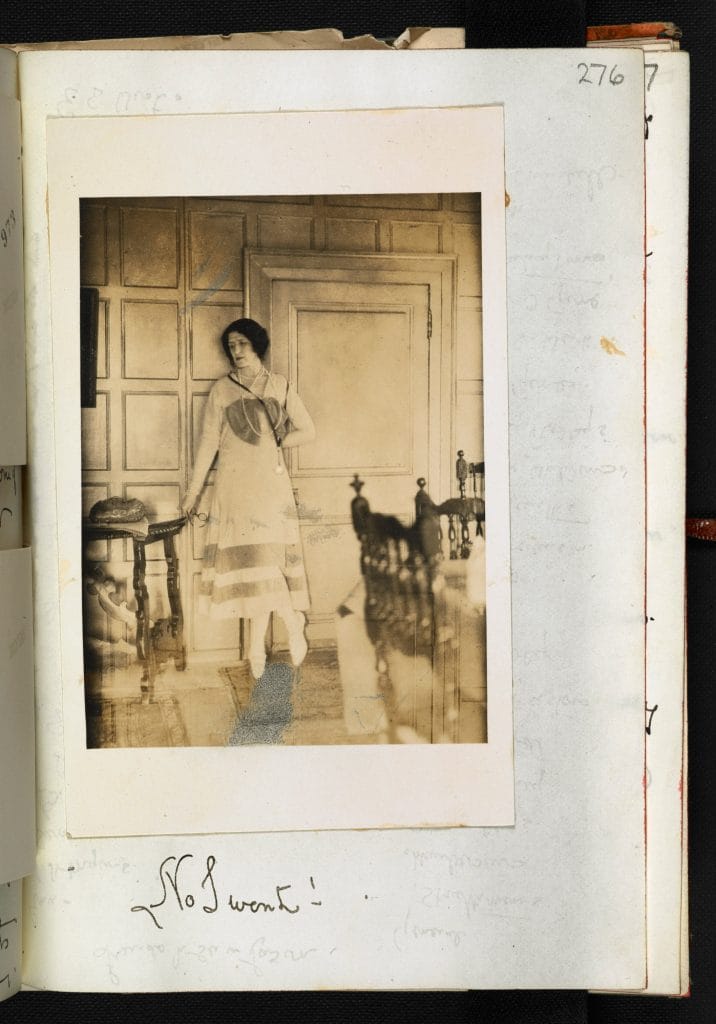

Does it matter that Virginia Woolf’s diary denies gloom, declaring that she enjoyed more happiness than nine out of ten people? The real woman was robust enough to tramp for miles each day, as she thought out her next day’s work, and her energy for work was prodigious.

Virginia Woolf’s triumph over family tragedies and illness offers a counter-narrative to the plot of doom and death often imposed on the lives of women – as though genius in a woman were unnatural. The depiction of Woolf’s suicide in The Hours opens with jolting retakes of a scene no one actually witnessed: the writer wading into the water. ‘Look at it!’ the camera insists, closing in, ‘Look at it!’ This approach slams home a ready message: be appalled.

Charlotte Brontë, Dora Carrington, Mary Wollstonecraft and Sylvia Plath

Such narratives of women writers invite us to see death as the crucial fact in the life. Will it ever be possible to detach Charlotte Brontë from the brooding tombstones that open Mrs Gaskell’s narrative of her friend’s life? The Brontës’ tombstones are fixed before us at the outset of the story. Mrs Gaskell is intent on presenting a slave to duty in the shadow of tombstones; she has less to say about the burning centre of Charlotte’s existence: the creative fire. The biographer directs our attention away from the exhilaration of writing, stressing in place of genius its obliteration. This approach distorts our response. It whips up a dubious blend of sentimentality and pity.

Sex provides another routine narrative: female wantonness en route to death. In the biopic of a member of Virginia Woolf’s circle, Carrington, our eyes are directed towards her irregular sex life – the banality of heaving bottoms – followed by the sensationalism of suicide, with only a belated glimpse of Dora Carrington’s prime gift: her paintings. These appear only at the close, obscured by the credits, as viewers are gathering up their coats to leave the cinema.

In the same year as Virginia Woolf published her feminist treatise A Room of One’s Own, in 1929, she wrote a biographical essay, ‘Mary Wollstonecraft’ – Wollstonecraft was the first to make a systematic case for women’s rights in her Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). Woolf’s focus is on Wollstonecraft’s resilience, instead of casting her as a depressive and licentious termagant. For 200 years Wollstonecraft’s life has been distorted by emphasis on attempted suicide. It took Virginia Woolf only three pages to reveal that what was crucial to this life was not depression, which is common, but political honesty, which is rare: that and Wollstonecraft’s capacity to ‘cut to the quick of life’.

Distortions of Mary Wollstonecraft and Dora Carrington, as well as the popular obsession with Sylvia Plath’s suicide at the expense of her poetry, reveal a wider context for popular fascination with Virginia Woolf’s death. What promotes this? Can it be that pity alleviates envy of greatness? A Room of One’s Own recalls how odd a female writer used to appear to her contemporaries, and how forbidding it would have felt to put pen to paper in times gone by. ‘That singular anomaly the female novelist’, sings the Lord High Executioner in The Mikado, ‘I don’t think she’d be missed. I’m sure she’d not be missed.’ Could there still be a lurking notion that female creativity is of its nature freakish?

‘The fact that suggests and engenders’

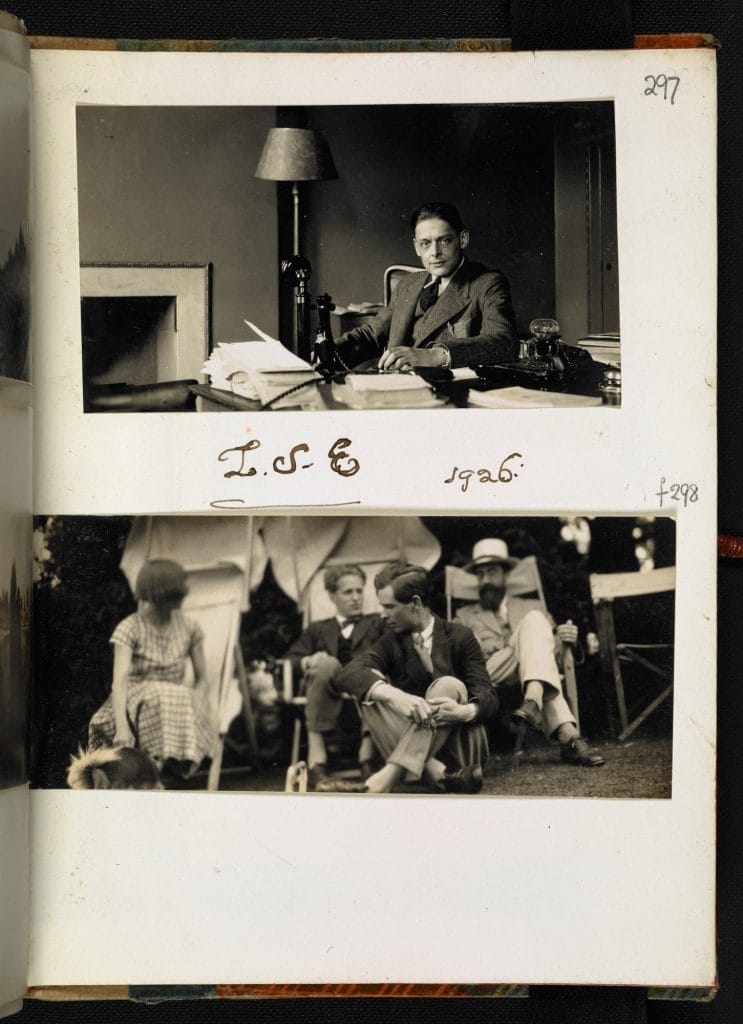

If so, it’s open to biography and future biopics to select for the creative aspect, as Woolf recommends in ‘The Art of Biography’ (1940). The biographer, she says, ‘can give us much more than another fact to add to our collection. He can give us the creative fact; the fertile fact; the fact that suggests and engenders.’ One such fact is that when German invasion seemed imminent, it was the supremely sane Leonard who proposed suicide to a somewhat reluctant Virginia. Leonard’s apprehension was justified: as a Jew, he and his wife were already on Himmler’s list for immediate arrest.

The ‘Outsider’

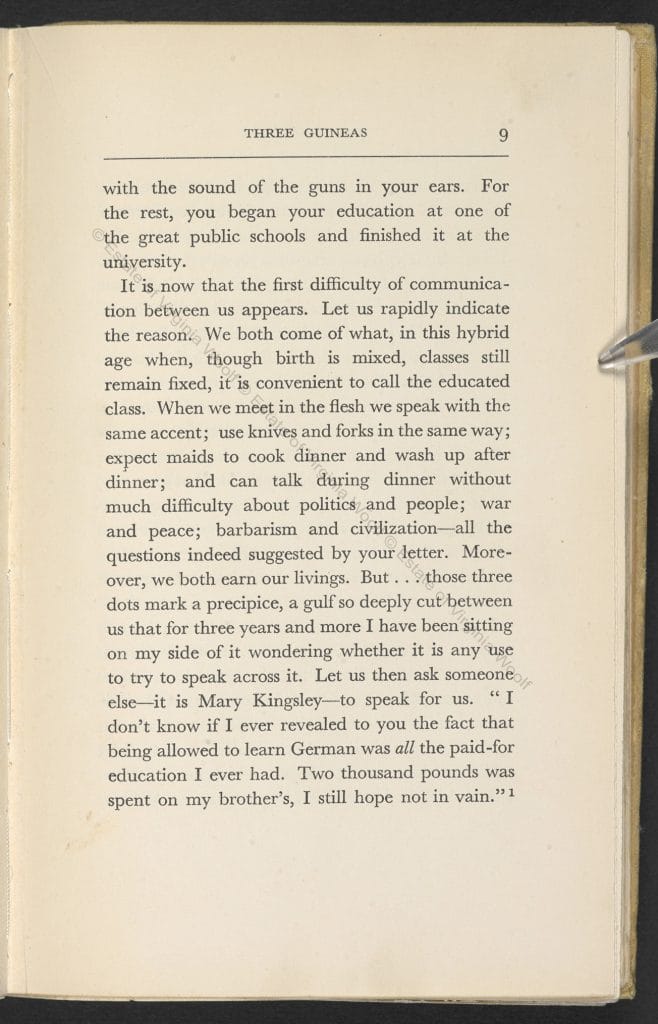

Popular interest in suicide has muffled somewhat the politicised public voice that Virginia Woolf developed in the 1930s, extending the feminism of the 1920s to a confrontation of power in all its manifestations. In her chosen role as ‘Outsider’, calling on like-minded women to form a Society of Outsiders, she speaks out against vainglorious rhetoric, militarism, medals and the strutting aspect of honour.

As German bombers flew nightly over Rodmell in August 1940, she shook free from war propaganda, which attributed insane love of power to an occasional madman. Reframing her forebears’ attacks on slavery, she suggested that we are all enslaved, irrespective of nationality, by ‘a sub-conscious Hitlerism in the hearts of men’: the wish to dominate. The word ‘slavery’ reverberates through one of her most original essays, ‘Thoughts on Peace in an Air Raid’. It warns that ‘Hitlerism’ will not be confined to ‘the enemy’, but will infiltrate the mindset of fighters on one’s own side.

In her last years Virginia Woolf conceived a right to vote not for one party or another but against the whole edifice of power. ‘I feel myself enfranchised till death, & quit of all humbug’, she records in her diary. On her long daily walk near Rodmell, a new sense of independence had whirled her ‘like a top miles upon miles over the downs’. The exhilaration of such ‘moments of being’ will surely outlast a stale fixation on the writer’s death.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Lyndall Gordon

Lyndall Gordon has written six biographies, including The Imperfect Life of T. S. Eliot (Virago, revised edition 2012) and Virginia Woolf: A Writer’s Life (Virago, revised edition), as well as two memoirs. She is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. Lyndall grew up in Cape Town and, having studied at Columbia in New York, she came to England in 1973 through the Rhodes Trust. Lyndall is Senior Research Fellow at St Hilda’s College, Oxford where she specialises in nineteenth and twentieth-century literature.