‘Waking the Sleeping Books’: Bloomsbury and the Crescent Moon Group in China

As Western literature is no longer banned, the literary connection between writings from China and the West is reawakening. The connection between the two dates back decades: this article discusses the striking parallels between the Bloomsbury Group and the Crescent Moon Group in terms of the historical background, aesthetic stance and relationship between art and politics; the prominent use by writers from both Groups of the ‘stream of consciousness’ technique is also considered.

Avant-garde artists in mainland China often speak of the need to ‘wake sleeping books’. After Mao Zedong’s demise in 1976, Western literature – no longer banned by Marxist critics – was reintroduced into China. Since then, historians and literary critics in both nations have been working in archives and libraries, seeking to reawaken the writings as well as the historical and literary connections that existed between China and England in the Republican Period from 1911 through to the 1940s.

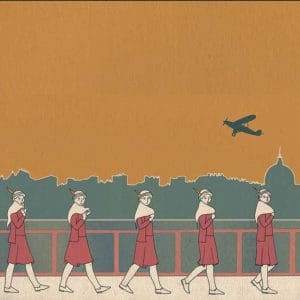

This period of modernism or mo-deng was a dynamic era of cultural and aesthetic openness between England and mainland China. It was during this time that Chinese culture started to take root in the imaginations of the so-called Bloomsbury Group, and to appear in British aesthetic and artistic expression. The Chinese landscapes in the translations of Tang poetry by Arthur Waley; landscape paintings on scrolls at the first International Chinese Exhibition of Art in Burlington House, London, in 1937; blue and white willow-pattern china in every British cupboard; Anglo-Chinoise designs influencing Chinese garden design; the Chinese pagoda in Kew Gardens; objets d’art; ceramics and the fashion for Chinese dresses in the Liberty department store – all point to a new international focus in British modernism.

The Bloomsbury Set formed in Edwardian London in about 1904 in the neighbourhood known as Bloomsbury, and was made up of artists and intellectuals from the worlds of literature, painting, economics, politics, law and colonial administration. Though they were the ‘unconscious inheritors of a tradition’, as Virginia Woolf would say, they made their mark by rebelling against certain Victorian cultural conventions and sexual and social standards. This group, like the Crescent Moon Group was described in many ways: by those who were a part of it, those on the fringes, those who were fascinated by it, those who condemned it and those who were repelled by its sexual libertinism, culture and politics. Perhaps it is most accurate to say that it was a group of friends, public intellectuals, writers and artists that between 1904 and 1932 became one of the most important literary and artistic circles in England. Some of the individuals in this circle were Virginia Woolf, Leonard Woolf, Arthur Waley, Vanessa Bell, Roger Fry, G L Dickinson, Bertrand Russell, Duncan Grant, E M Forster, John Maynard Keynes, Lytton Strachey (the first generation), Julian Bell, Quentin Bell and Angelica Bell (the second generation).

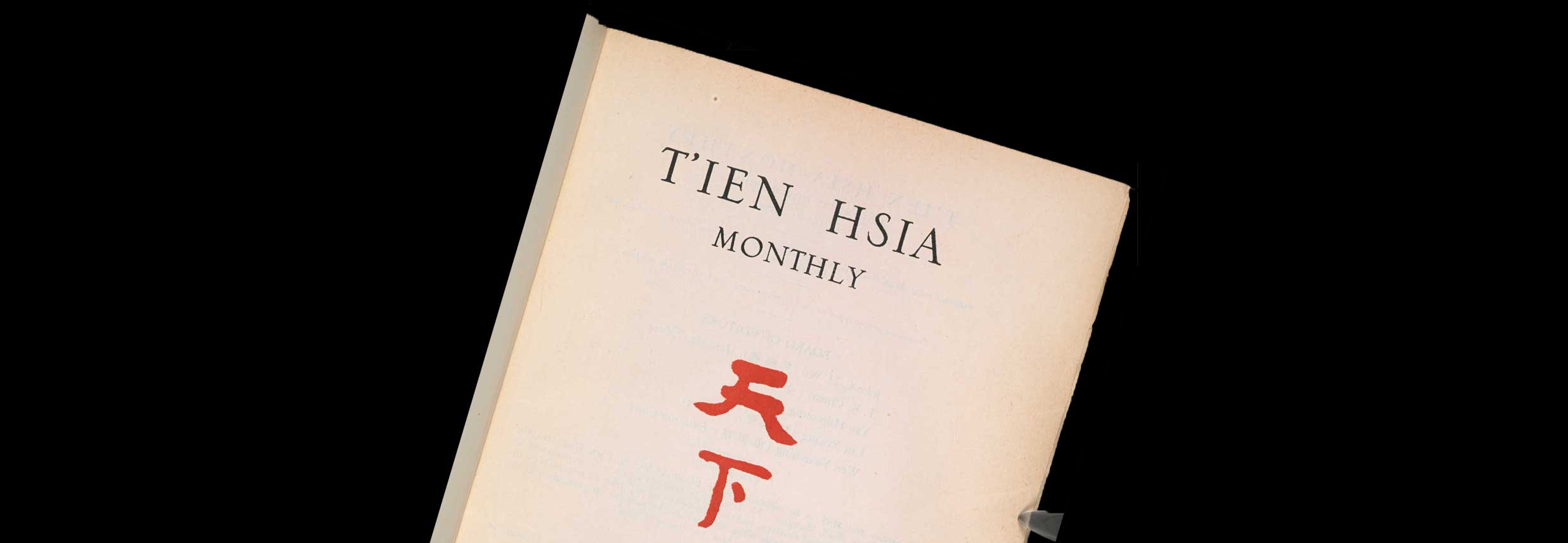

In the past decade in China, there has been a resurgence of interest in this circle, just as there has been in the Crescent Moon Group. Indeed there are striking parallels to be drawn between the two groups. Both had an oppositional aesthetic stance during a time of rising nationalism; both grappled with the relationship between art and politics. The Crescent Moon Group, formed around 1923 in Beijing, took its name from a collection of poems of the Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore, and sought to collapse the struggle between the East (China) and the West (England and the US), by adopting the imagery of a third nation, India, in the image of a Crescent Moon (Sin Yue Pai). Founded by the poet, Xu Zhimo, the group included educated individuals affiliated with Beijing University, most of whom had studied abroad in England and America, and it too evolved from friendships among artists and intellectuals of two generations: Xu Zhimo, Chen Yuan, Hu Shi, Wen Yiduo, Shen Congwen and Ling Shuhua, among others. Classified as a political clique, the group was attacked for being detached from the social fervour of the times and associated with an ‘art for art’s sake’ philosophy – as was Bloomsbury. Drawn to the ideas and art of the West, they were labelled at various times as ‘Anglo-American identified’, ‘Western’, ‘capitalist’, ‘bourgeois’, ‘rightist’, ‘gentlemen’, ‘Nationalist’, ‘anti-Soviet’ and ‘revolutionary’. Xiao Qian, the writer and critic, in a 1995 conversation, reported that they were described as the ‘Bloomsbury of China’ because they were perceived as living in ‘an ivory pagoda’ just as Bloomsbury was perceived as living in its ‘ivory tower’, detached from politics (though this did not apply to all of its members).

The connection between the two groups was not merely theoretical, however.

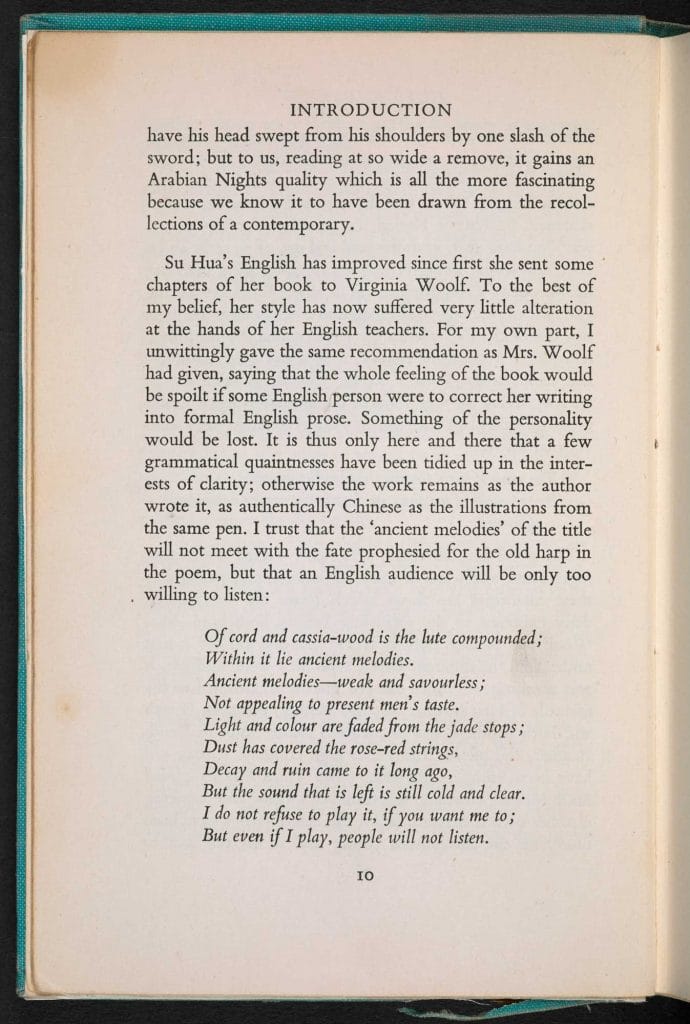

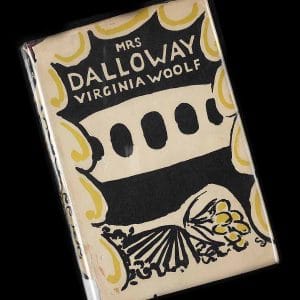

Ling Shuhua, was a writer and New Crescent Group member. Her husband, Chen Yuan, was a leading historian, literary critic and intellectual and a key figure in the group; he founded the Contemporary Review magazine (1924–28), which became a forum for the political and literary works of the New Crescent Group. In 1945 Ling Shuhua began a clandestine relationship with Julian Bell, Virginia Woolf’s nephew, who was then teaching at Wuhan University. Through this relationship, she developed a correspondence with Woolf herself, swapping and discussing their artistic ambitions. In her collections of short stories, Flowers in the Temple (1928), Women (1930) and Two Little Brothers (1935), Ling wrote of women’s position in Chinese families and society, relations between men and women, women’s friendships, children and deteriorating domestic situations. She not only shared Woolf’s interest in women’s lives; Ling too experimented with the technique of turning inward to capture women’s interior monologues in these stories, in a style approaching Woolf’s ‘stream of consciousness’ technique in works such as Mrs Dalloway and To the Lighthouse.

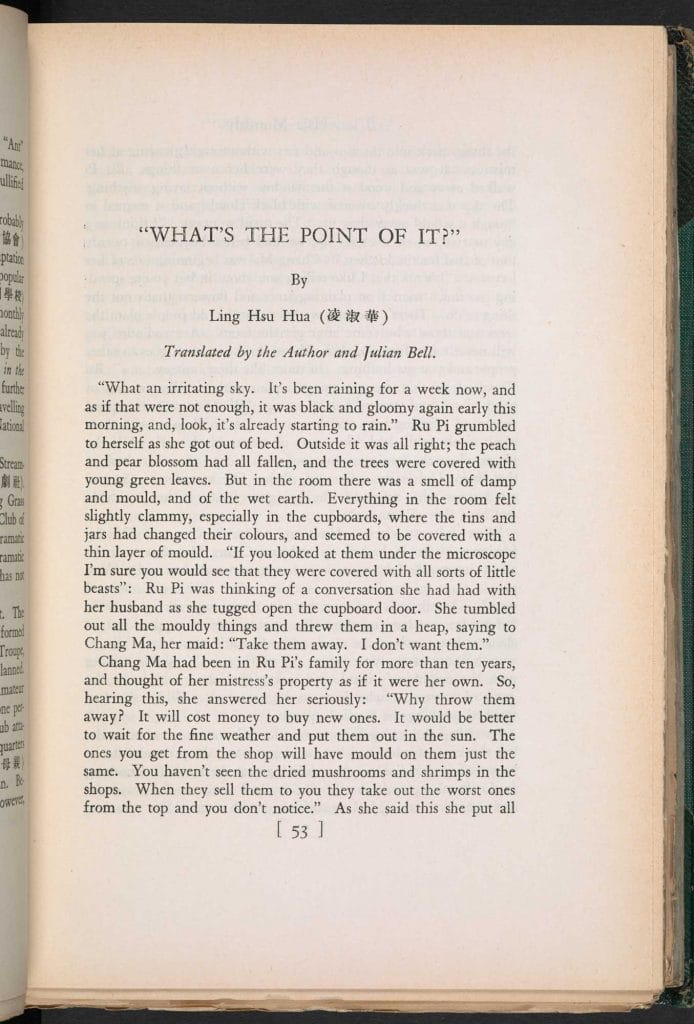

In Ling’s story ‘What’s the Point of It?’, for example, she explores the pointless feelings of Ru Pi, an educated, upper-class woman. Her story begins in the mind of her protagonist:

‘What an irritating sky. It’s been raining for a week now, and as if that were not enough, it was black and gloomy again early this morning, and look it’s already starting to rain,’ Ru Pi grumbled to herself as she got out of bed. Outside it was all right: the peach and pear blossoms had all fallen, and the trees are covered with green leaves. But in the room there was a smell of damp and mold.

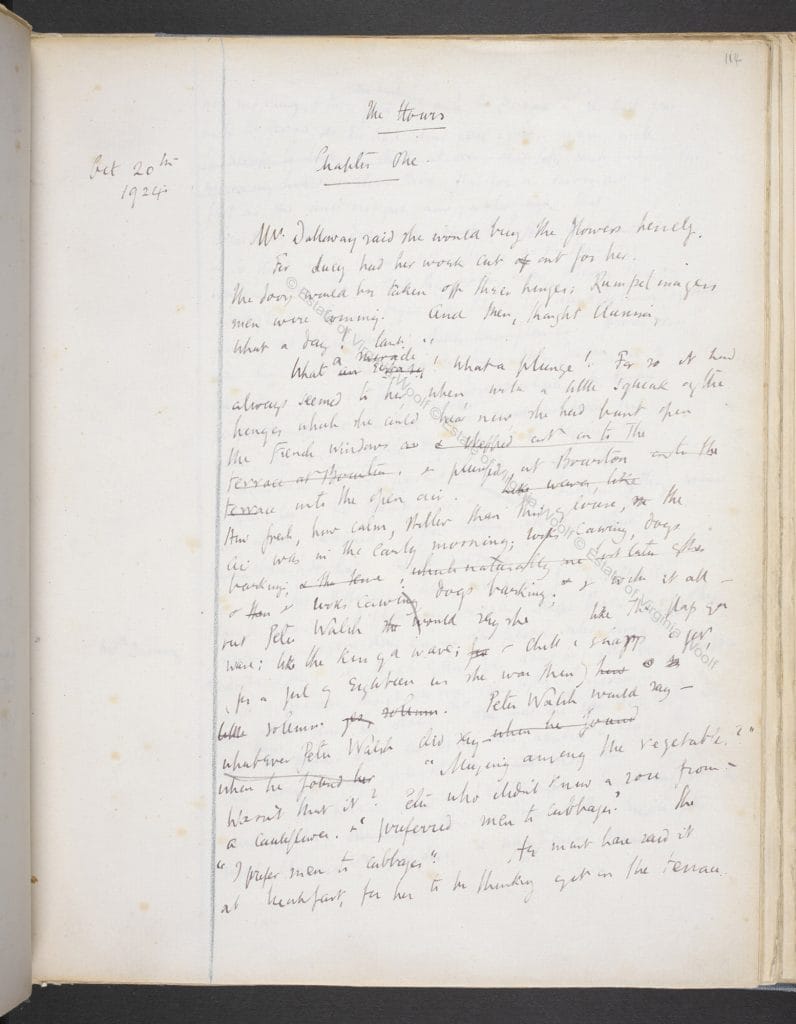

Compare this to the opening of Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway – the character is an upper-class woman, wife of a member of Parliament – which begins on a finer day in June:

Mrs Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself. For Lucy had her work cut out for her. The doors would be taken off their hinges. Rumpelmayer’s men were coming. And then, thought Clarissa Dalloway: what a morning – fresh as if issued to children on a beach.

Ru Pi has a maid, Cheng Ma, and reflects negatively on her intrusiveness, she observes a busy mother, hears a woman crying next door and comments on women out shopping. Feeling the ‘pointlessness’ of her life, she looks at it through the eyes of her maid and rickshaw driver, who view her as ‘rich’ and ‘important’. She thinks, feels, sighs, sees and reflects on the meaning of her life as a ‘bourgeois’ woman. Likewise, Mrs Dalloway, the party hostess, reflects on her dress, passing cars, a day in June, poor Armenians, her youth, love affairs that never came to pass, and eventually – prompted by the news of the suicide of a man named Septimus Warren Smith – on the meaning of his death and the recent war.

Both writers experiment in telling women’s lives from the inside – through ‘stream of consciousness’ – while they criticise the social system and its effects on women. Placing these works by Virginia Woolf and Ling Shuhua as well as their literary homes, the Bloomsbury and Crescent Moon Groups, side by side, reveals not ‘influence’ – an overworked category in literary studies – but rather shared affinities. It also brings into relief the pre-existing cultural need in England and China in the 1920s and 1930s for an aesthetic vision during a time of political and social ferment in both countries.

脚注

- This article is adapted from my book(Lily Briscoe’s Chinese Eyes: Bloomsbury, Modernism and China . Columbia S.C.: University of South Carolina Press, 2003. Translated into Chinese by Shanghai Bookstore Press, 2008.

- Woolf’s novel was translated into Chinese in 1997 by Qu Shijing; he has written about her use of this interior monologue.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Patricia Laurence

Patricia Laurence is a writer, critic and Emeritus Professor of English of the City College of New York, CUNY. She is a specialist in transnational modernism, modernist women’s writing, Virginia Woolf and Bloomsbury studies, and Republican era literature of China. Her published works include The Reading of Silence: Virginia Woolf in the English Tradition (1994); Lily Briscoe’s Chinese Eyes: Bloomsbury Modernism and China (2003), and a short biography, Julian Bell, the Violent Pacifist (2005). Her biography of Elizabeth Bowen is forthcoming from Northwestern UP.