English Literature in Translation

From the incomparable Shakespeare to Angela Carter the ‘mad witch’; from ‘Zei She’ (Oliver Twist) translated by Lin Shu to the world-famous ‘consulting detective’ Sherlock Holmes; and from late Qing/Republican China to the modern 21st-century country that has opened its doors to the world, believing ‘Chinese learning for the essence, Western learning for practical use’. The stories from England which were once seen as the means of changing China first started to enter the consciousness of the Chinese people in the mid 19th century. But how did English literature travel to China, and what are the stories behind these journeys? These newly commissioned articles explore the journeys of some of the most iconic works of English literature to China – when they were first translated, why they were selected for translation, the ambiguous relationships and conflicts between the original works and their translations, the linguistic and cultural challenges they pose, and how they were received and perceived.

1853 English literature in China

Western literature was first introduced to China by Christian missionaries. John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress was translated into classical Chinese in 1853 by a Scot, William Chalmers Burns. Twenty years later, Li Shao translated Edward Bulwer Lytton’s Night and Morning, which was published in the literary magazine Yinghuan Suoji; this was the first piece of English literature translated by a Chinese person. Following these early pioneers, a number of intellectuals from the late Qing/early Republican period started to translate Western literature and publish commentaries and literary criticism specifically about English literature. These young and ambitious Chinese were determined to use translated Western literature to overthrow the old system and traditions, and invoke new and forward thinking.

查看更多1896 Sherlock Holmes in China

Crime fiction was one of the most popular literary genres in the late Qing period. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories were introduced to China soon after they were published in the UK, and one of the earliest translated editions first appeared in the Shiwu newspaper, the early reformist paper edited by the famous intellectual Liang Qichao. To adjust Western crime fiction to the taste of Chinese audiences at that time, the translator cut and rewrote the stories, but despite these changes they were not very well received.

However, the enthusiasm for translating and publishing Sherlock Holmes stories remained high. In the next two decades translations of Sherlock Holmes stories often appeared in various kinds of literary magazines and publications, and most of the translators were the popular writers (a group of Chinese authors now known as the ‘Mandarin Duck and Butterfly School’, Yuanyang hudie pai). Even if Western crime fiction was often compared with Chinese Gongan literature, this literary genre (along with Western science fiction) was still regarded as an important means to change society and save the country at a time when China was being ‘colonised’; therefore its introduction and translation was encouraged and praised by Chinese intellectuals and scholars.

1902 Percy Bysshe Shelley in China

Incantations such as ‘If Winter comes, Can spring be far behind’ have given many Chinese the joy of hope, even in the darkest hours.In fact, odd lines from Percy Bysshe Shelley’s ‘Ode to the West Wind’, ‘To a Skylark’ and ‘The Cloud’ would at least ring a bell with almost all college-educated Chinese, even if they have not actually read or tried to commit to memory these wildly popular lyrics in English or Chinese translations. Longer works such as Adonaïs, Prometheus Unbound, The Cenci and The Revolt of Islam have all received their share of attention too. Shelley may not quite be one of the greatest Western authors known in China – in the league of Shakespeare, Tolstoy and Dante – but he is certainly one of the best known and most iconic, a lofty position he initially reached during the first half of the 20th century. This article tells the story of the translation and the reception history of Shelley in China since he was first introduced to Chinese readers in 1902.

查看更多1903 From ‘Sha Ke Si Bi’ to Shakespeare (‘Sha Shi Bi Ya’): The contemporary reinterpretation of Shakespeare

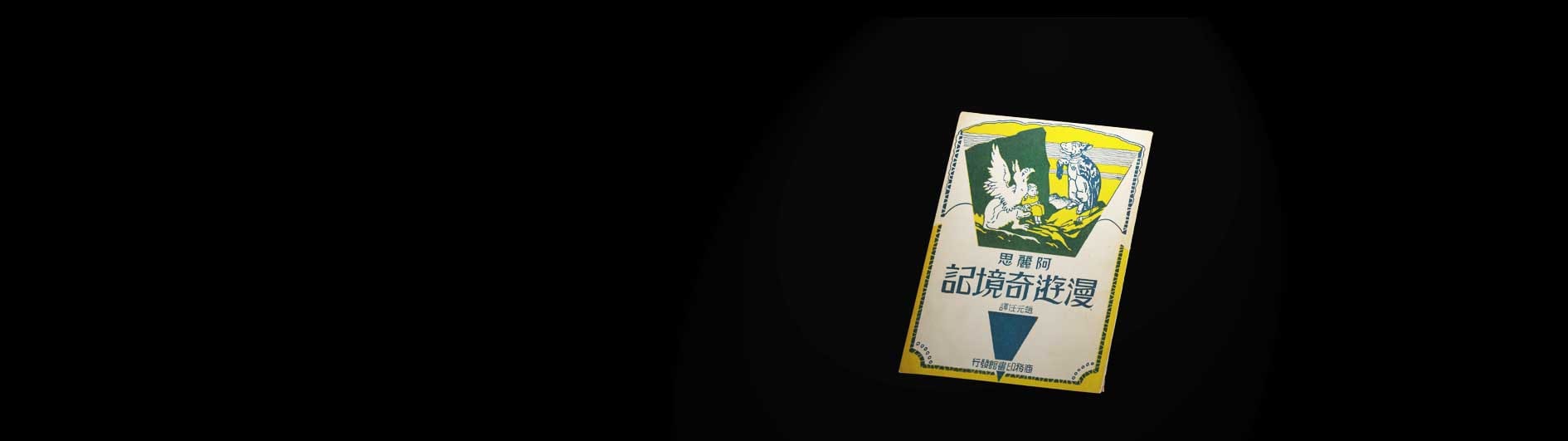

Xiewai Qitan, a collection of ten selected stories from the Lambs‘ Tales of Shakespeare, was published in 1903 by a local publishing house, Shanghai Dawenshe. This was the first classical Chinese translation of the works of Shakespeare, even though his name had already shown up in a few works by diplomats and missionaries. In 1904, Yinbian Yanyu Ji, the full translation of The Tales of Shakespeare by Lin Shu and Wei Yi, was published. This version had a considerable impact and inspired a number of later translations.

查看更多In 1922, Tian Han published his translation of Hamlet in Shaonian Zhongguo (vol 2, series 12); this was also the first time that a play by Shakespeare had been translated into vernacular Chinese, and it was followed by many other new translation experiments. Although the arguments about different ways of interpretation – whether to use literal translation or free translation – have never stopped since the first translation was made in 1903, the British icon William Shakespeare has become one of the most familiar foreign names in China.

1908 What triggered the birth of Chinese children’s literature?

The origins and development of modern Chinese children’s literature were heavily influenced by children’s literature from the West. The symbolic icon which signals the beginning of Chinese children’s literature, the Tonghua journal, was first published by the Commercial Publishing House in 1908, and included a number of translated English children’s stories. Zhou Zuoren and Lu Xun read numerous books and essays on children’s literature; when they studied in Japan they selected several works to translate and publish, one being Yuwai Xiaoshuo Ji (the collection of foreign literature) which includes the first Chinese translation of The Happy Prince by Oscar Wilde. At the same time, Zhuo Zuoren published a series of commentaries and literary criticism on children’s literature. These insightful works not only inspired a new generation of scholars and intellectuals on children’s literature, but also diversified the ‘New Culture’ and the May Fourth Movement.

1909 Translating Oscar Wilde

The earliest Chinese translation of Oscar Wilde’s work is a translation of The Happy Prince, which was published in Yuwai Xiaoshuo Ji (the collection of foreign literature) in Japan, a collaboration between Zhou Zuoren and Lu Xun. The Happy Prince opened the door to China for Oscar Wilde’s work; Wilde initially became well known for his works of children’s literature, but his fame and success grew through his plays that were seen as ‘Art written for the sake of Art’ in the 1920s in China. He is known as the master of the aestheticism movement, and hence received the attention of many pioneering Chinese intellectuals. The disturbing satire, witty puns and criticism of the upper classes in Britain were carefully translated into Chinese, ensuring that the satirical elements directed against society worked in a Chinese context.

查看更多1925 The Chinese ‘adventure’ of the Brontë sisters

Even though Chongguangji (‘See Light Again Story’) condensed and scaled down the famous novel Jane Eyre, this is apparently the first Chinese translation of any of the works of the Brontë sisters. Translated by Zhou Shoujuan in 1925, this novel is included in a collection published by the Shanghai Dadong Publishing House. Since then, Jane Eyre has been translated in many different editions; for instance, Wu Guang Jian and Li Jiye both translated Jane Eyre in 1935, Wu Guang Jian finishing the abridged translation in the novel titled Gu Nv Piaoling Ji, and Li Jiye releasing a full-length translation in serial form in the journal Shijie Wenku.

查看更多Although there had initially been controversies about whether the introduction of this sort of love story could help to save the country and enlighten the people, many works of the Brontë sisters such as Wuthering Heights still attracted strong interest from Chinese translators; indeed, many famous translations date from the first half of the 20th century. Over the last 100 years, the Brontës’ novels have become prominent cultural icons – through numerous adaptations and interpretations, the stories have become embedded in the personal histories and everyday lives of many Chinese readers.

2004 How to understand Angela Carter?

The introduction of Angela Carter’s works to China came fairly late, the first Chinese translation of her work appearing in Taiwan nearly ten years after she passed away in 1992. Carter’s books soon received an overwhelming amount of interest in mainland China, but her work poses certain challenges: all of the wit and humour, the complicated plots, the reinterpretation and rewriting of classical literature and fairy tales add up and make translation particularly difficult. To fully understand Carter and her works, the reader might have to get used to consulting numerous footnotes, and grappling with various metaphors, satires and clever imitations! As Salman Rushdie once said, ‘for the best of the low, demotic Carter, read Wise Children’.