Original manuscripts by five of the greatest writers in the English language will go on show in Shanghai for the first time in March 2018. ‘Where Great Writers Gather: Treasures of the British Library’ will feature drafts, correspondence and manuscripts by writers including Charlotte Brontë, D H Lawrence, Percy Bysshe Shelley, T S Eliot and Charles Dickens, alongside Chinese translations, adaptations and responses to their works.

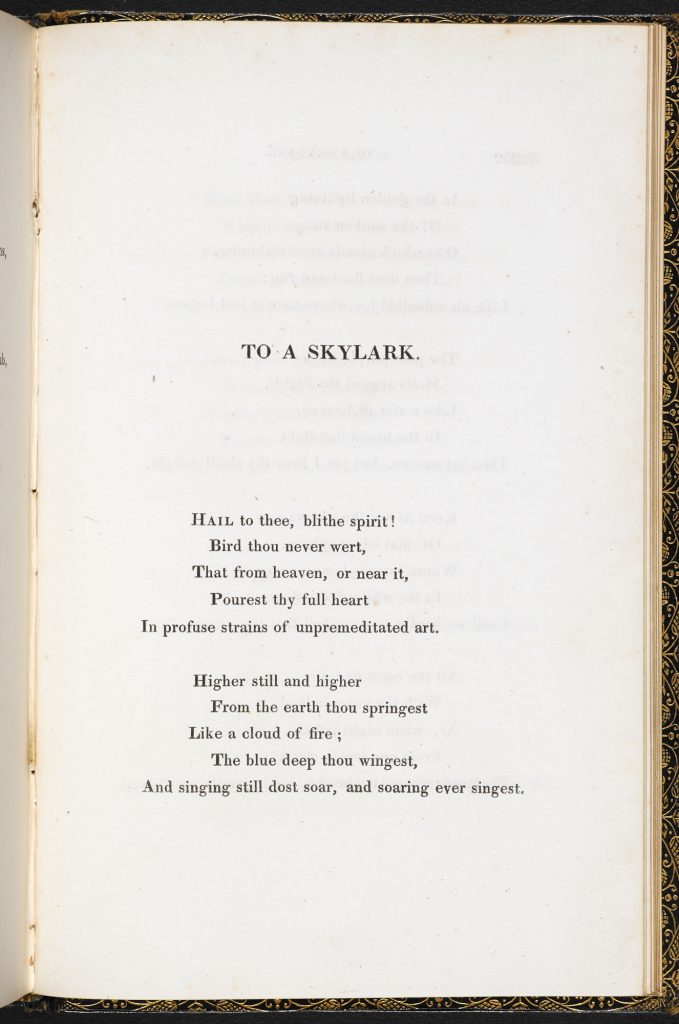

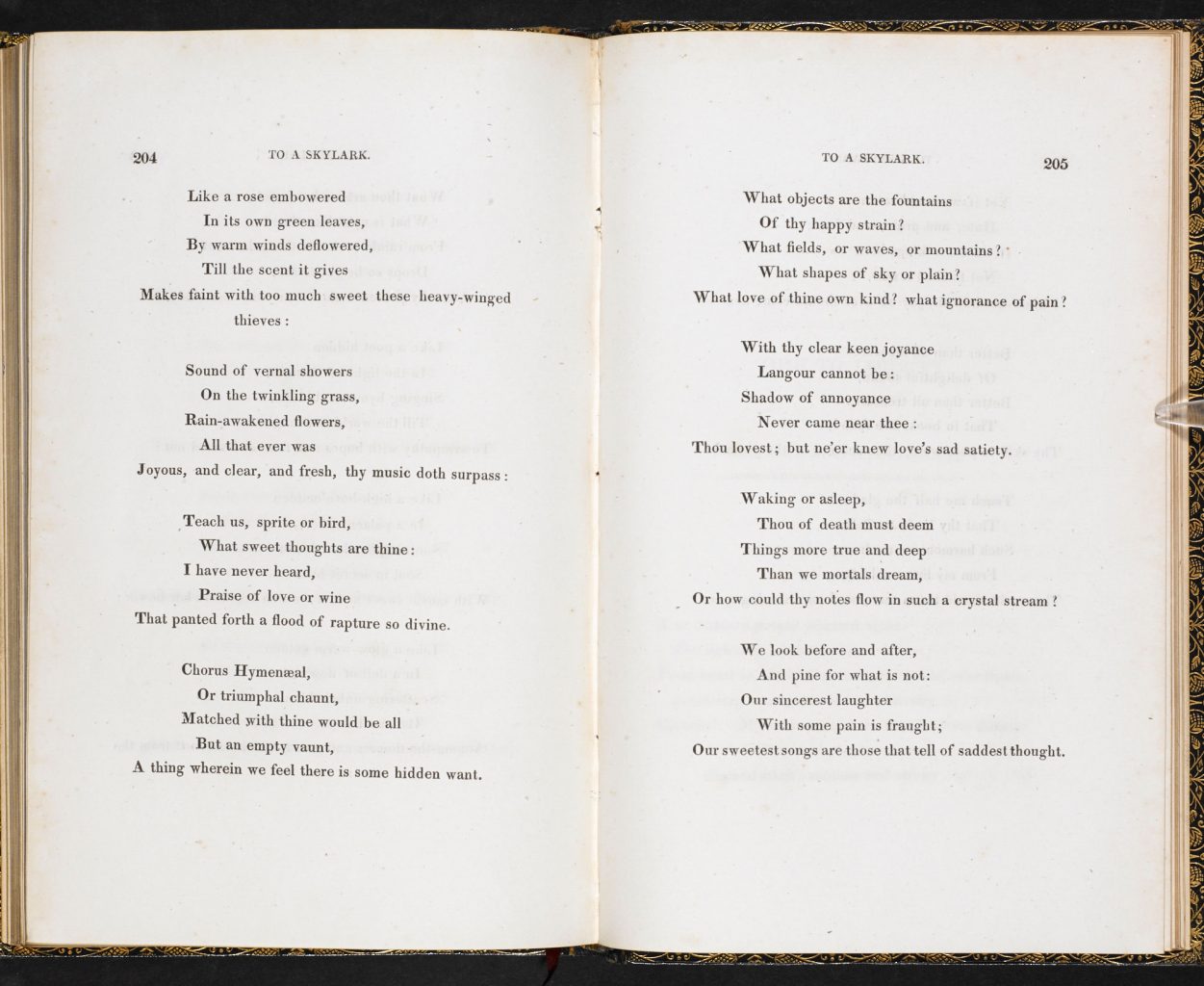

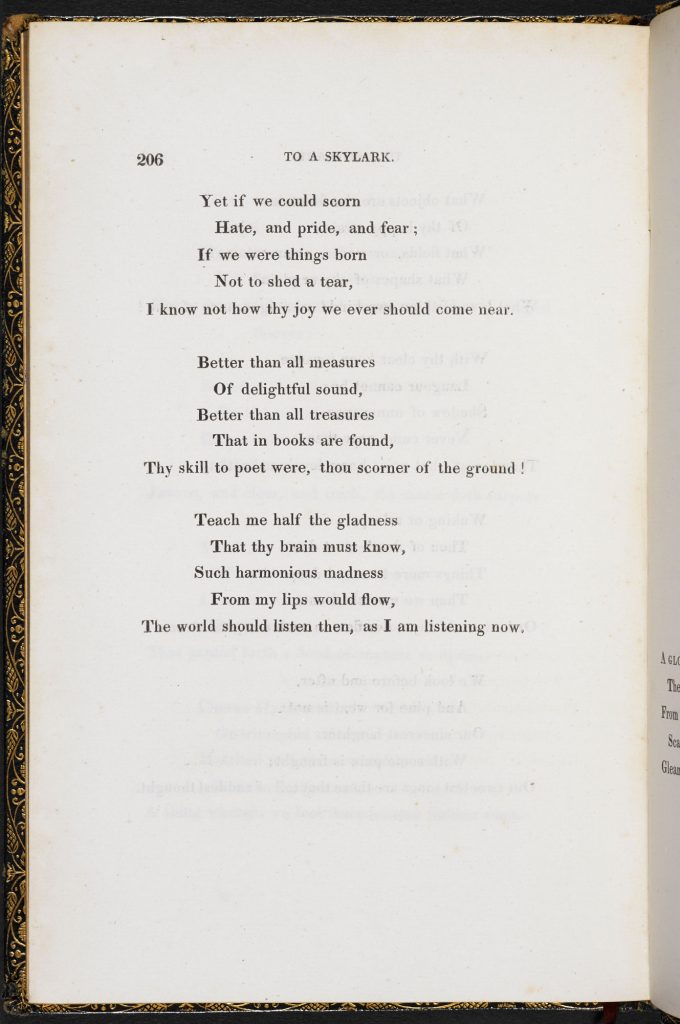

Percy Bysshe Shelley’s ‘To a Skylark’

出版日期: 1820 文学时期: Romantic

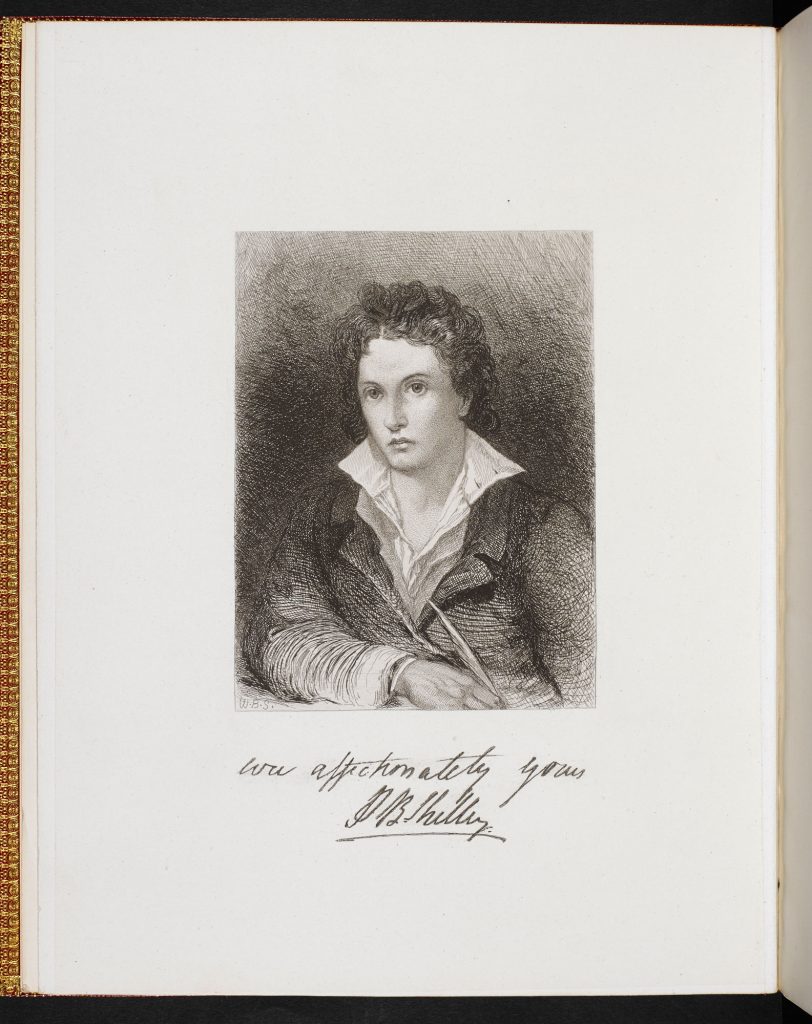

The Romantics believed that the healing power of the imagination could enable people to transcend their everyday circumstances and anxieties. This conviction features prominently in Percy Bysshe Shelley’s (1792–1822) ode ‘To a Skylark’, written in 1820.

Shelley composed ‘To a Skylark’ in the summer of 1820, when he was living in Livorno, a town on the north-west coast of Italy. It is one of his most accessible and popular poems. He begins by praising the evening flight of the skylark, then looks – without success – for examples of equivalent beauty, and finally asks the bird to teach him its ‘sweet thoughts’.

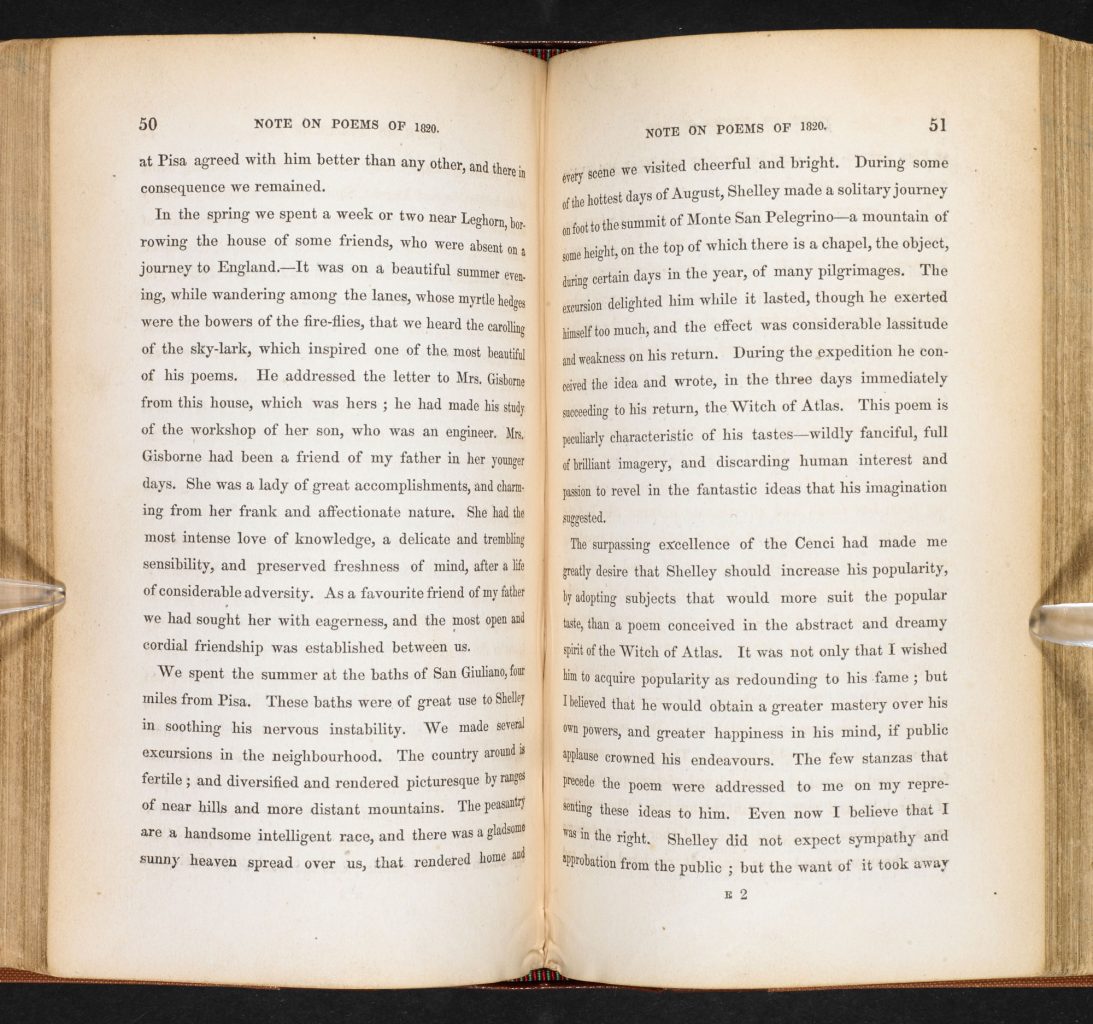

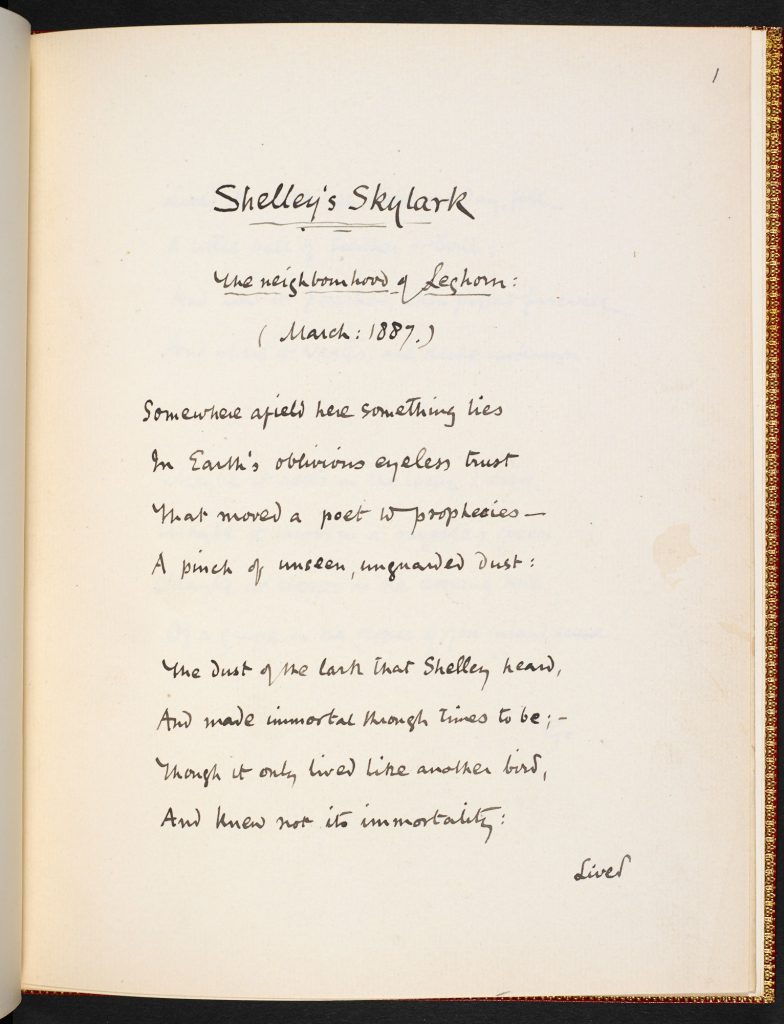

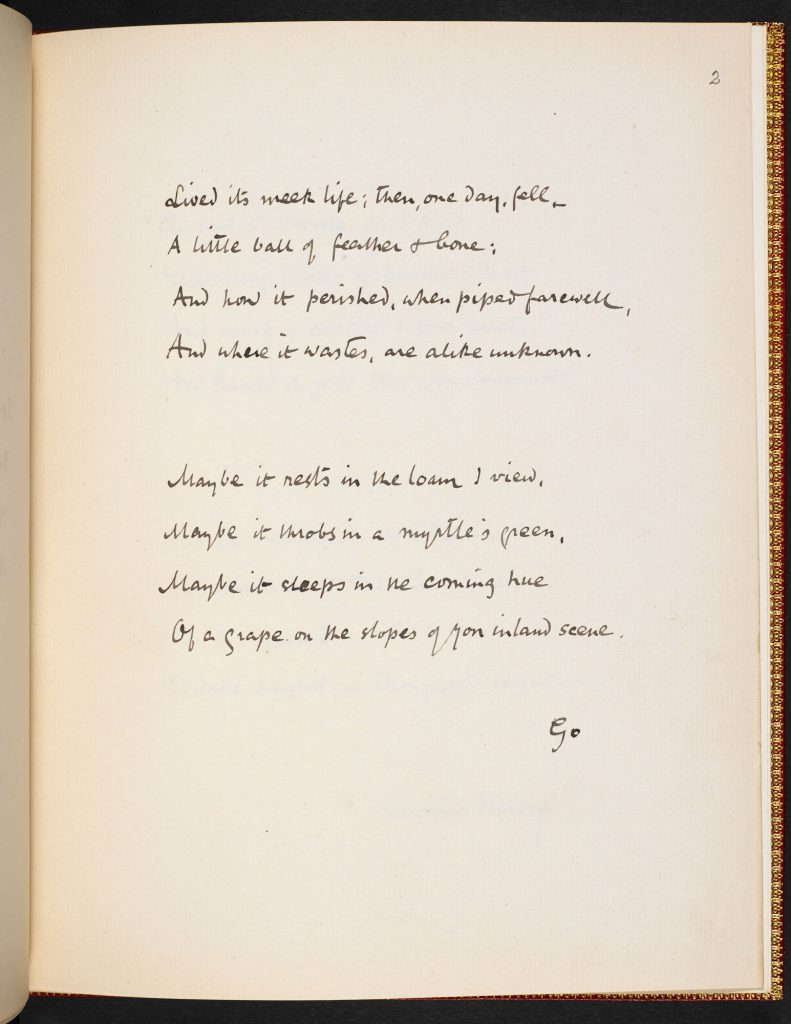

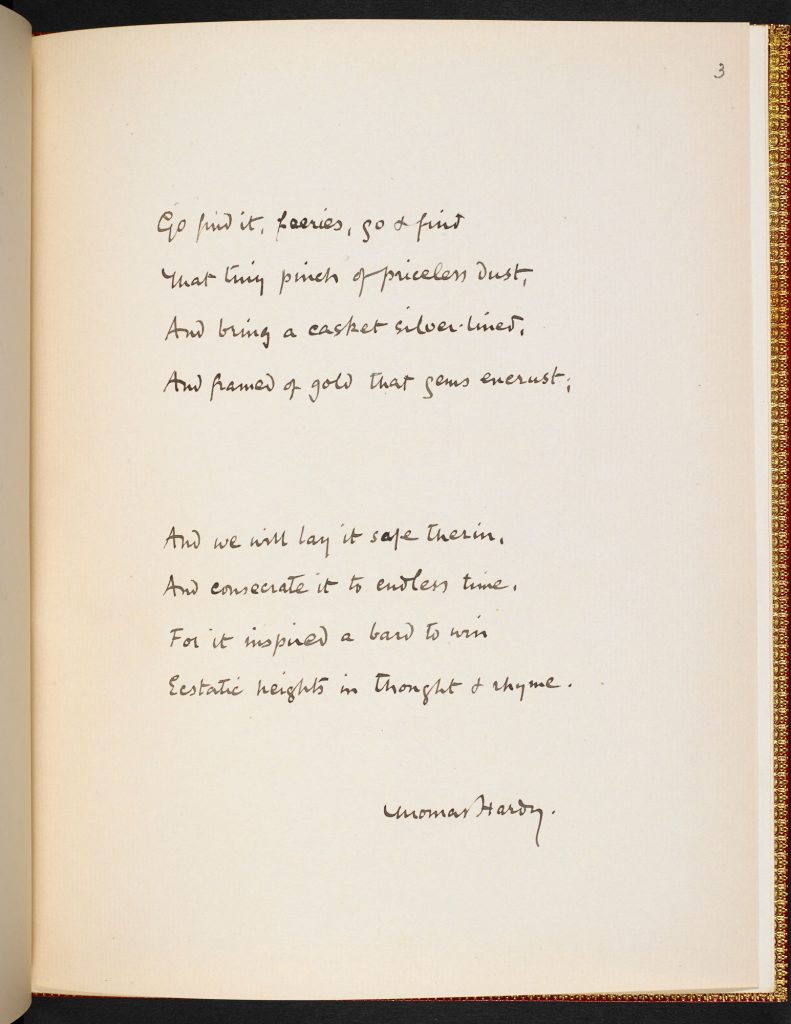

In her note to the poem, Mary Shelley traced its genesis to a particular summer evening: ‘while wandering among the lanes whose myrtle hedges were the bowers of the fire-flies … we heard the carolling of the skylark which inspired one of the most beautiful of his poems’. In an early poem, ‘Shelley’s Skylark’, the author Thomas Hardy imagined ‘The dust of the lark that Shelley heard’, and requests the ‘faeries’ to find it, together with a casket,

And we will lay it safe therein,

And consecrate it to endless time;

For it inspired a bard to win

Ecstatic heights in thought and rhyme.

‘To a Skylark’ is not, however, a description of a particular occasion, or a particular bird; rather, it is a search for something ideal and elusive, something which cannot, in the end, be captured in words.

‘Bird thou never wert’

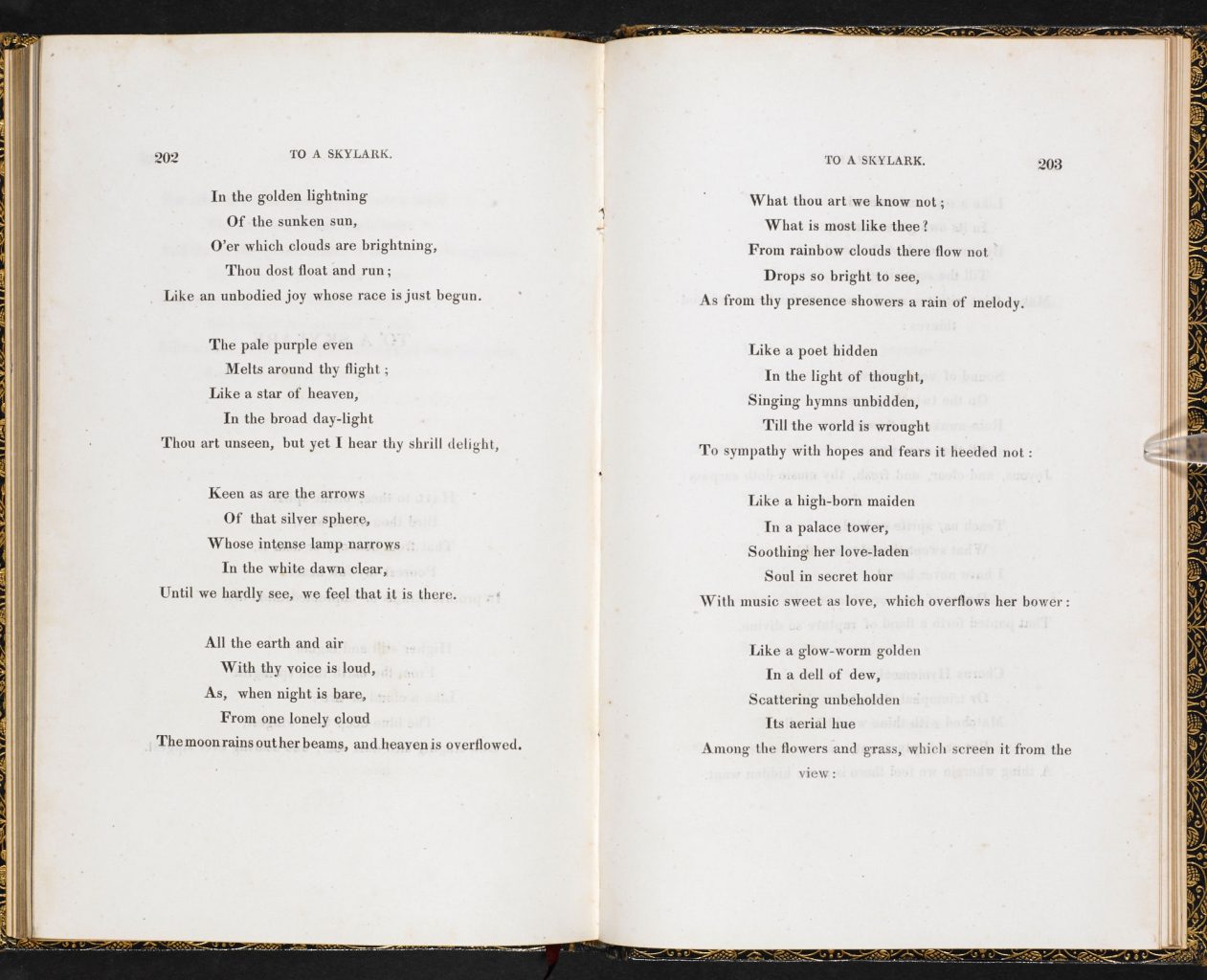

The skylark only sings when it is in the air, and usually from such a height that it is invisible to the human eye. ‘Bird thou never wert’ writes Shelley of this unseen presence, which is not so much a physical form as a joyous, disembodied voice that soars in the ‘deep blue’, that floats and runs in the golden light of evening. Like the keen light of Venus, the morning star, it narrows ‘Until we hardly see – we feel that it is there’.

‘What is most like thee?’ Shelley asks the skylark. Its melody is like the hymns sung by ‘a Poet hidden / In the light of thought’; the love songs of ‘a high-born maiden / In a palace-tower’; the ‘aerial hue’ cast by a glow-worm over ‘the flowers and grass which screen it from the view’; the scent given by a rose when ‘By warm winds deflowered’; and the sound of rain ‘On the twinkling grass’. And yet, admits Shelley, ‘All that ever was / Joyous, and clear and fresh, thy music doth surpass’.

‘Harmonious madness’

Shelley consequently asks the skylark to teach him its thoughts, compared to which, he believes, mankind’s wedding songs (‘Chorus Hymeneal’) and chants of triumph would be no more than empty boasts. The bird appears to be blissfully free of those things that weigh down human life. It seems ignorant of pain, languor and anger, and must have a deeper and truer knowledge of death, ‘Or how could thy notes flow in such a chrystal stream?’ Should the skylark ‘Teach me half the gladness / That thy brain must know’, Shelley writes in the concluding stanza, it would bring him an ‘harmonious madness’ of the kind Plato describes in Phaedrus, which Shelley had read in May 1819: ‘If anyone comes to the gates of poetry and expects to become an adequate poet by acquiring expert knowledge of the subject without the Muses’ madness’, says Socrates, ‘he will fail, and his self-controlled verses will be eclipsed by the poetry of men who have been driven out of their minds.’ [1]

‘Our sweetest songs are those that tell of saddest thought’

In ‘To a Skylark’ Shelley creates, through a series of fine images and similes, a most beguiling evocation of the skylark’s carefree existence. Equally, he vividly evokes contrasting human characteristics:

And pine for what is not –

Our sincerest laughter

With some pain is fraught –

Our sweetest songs are those that tell of saddest thought.

Quoted on its own – as it often is – this famous stanza can seem sentimental and self-pitying, just as the poem’s lyrical images of earthly beauties can, when taken out of context, come across as rather meaningless. One can see why Matthew Arnold described Shelley as ‘a beautiful but ineffectual angel, beating in the void his luminous wings in vain’.[2] Read in its entirety, however, ‘To a Skylark’ brilliantly illustrates Shelley’s conviction that the human mind, and, by extension, human society, operates not according to fixed mental or emotional states, but according to a constantly changing and never resolved tension between the body and soul, the physical and the imagined, despondency and optimism, harsh reality and idealism. The joyous existence represented by the skylark is never seen, still less achieved, but it remains a vivid and keenly envisioned ideal. It is the process which matters, and Shelley’s great achievement in this and other poems is to capture this fluidity in poetic form. As he wrote in Prometheus Unbound (1820):

Language is a perpetual Orphic song,

Which rules with daedal harmony a throng

Of thoughts and forms, which else senseless and shapeless were.

脚注

Contributor: Stephen Hebron

Stephen Hebron is a curator at the Bodleian Library, Oxford University. He has published widely in the field of British Romanticism, including most recently John Keats: A Poet and His Manuscripts (2009) and Shelley’s Ghost (2010).

The text in this article is available under the terms of a Creative Commons License.