Charles Dickens and the Victorian Christmas Feast

Simon Callow explores Charles Dickens’s depiction of the Christmas feast and investigates the origins of England’s festive culinary traditions.

Charles Dickens’s conception of Christmas is fundamentally connected to the idea of feasting, which is profoundly expressive of the human happiness that he believed the festival should promote. It plugs directly into the medieval and pagan idea of defying the evil forces apparently overtaking nature, as well as a storing-up of resources to face the wintery fight ahead.

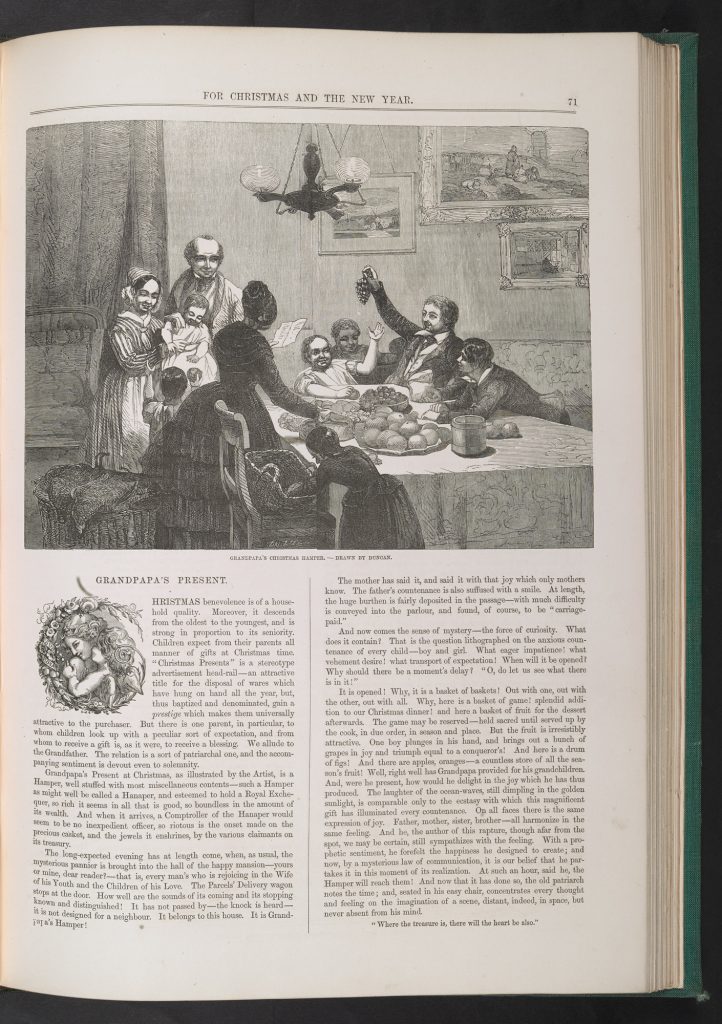

For Dickens, it is the coming together of people around a table, the celebration of their humanity, the sharing of their bounty, the reward of indulgence (even if that is only once a year) that is the essence of the meal. For an abstemious man, his ability to render simple food and drink overwhelmingly desirable is astonishing. But behind the sensuality always lies the symbol. The preparation is as life-enhancing as the consumption. ‘The party always takes place at uncle George’s house’, he writes in A Christmas Dinner, the first Christmas piece he wrote:

but grandmamma sends in most of the good things, and grandpapa always will toddle down, all the way to Newgate Market, to buy the turkey, which he engages a porter to bring home behind him in triumph, always insisting on the man’s being rewarded with a glass of spirits, over and above his hire, to drink ‘a merry Christmas’ and ‘a happy new year’ to aunt George.As to grandmamma, she is very secret and mysterious for two or three days beforehand, but not sufficiently so to prevent rumours getting afloat that she has purchased a beautiful new cap with pink ribbons for each of the servants, together with sundry books, and pen knives, and pencil cases, for the younger branches; to say nothing of divers secret additions to the order originally given by- aunt George at the pastry cook’s, such as another dozen of mince pies for the dinner, and a large plum cake for the children.On Christmas Eve, grandmamma is always in excellent spirits, and after employing all the children, during the day, in stoning the plums, and all that, insists, regularly every year, on uncle George coming down into the kitchen, taking off his coat, and stirring the pudding for half an hour or so, which uncle George good-humouredly does, to the vociferous delight of the children and servants.

The valiant struggle of the Cratchits (the impoverished hard-working family in Dickens’s A Christmas Carol) to make their meagre ingredients feel like a feast is triumphantly successful, and one of the most affecting sections of the novel.

There never was such a goose. Bob said he didn’t believe there ever was such a goose cooked. Its tenderness and flavour, size and cheapness, were the themes of universal admiration. Eked out by apple-sauce and mashed potatoes, it was a sufficient dinner for the whole family; indeed, as Mrs Cratchit said with great delight (surveying one small atom of a bone upon the dish), they hadn’t ate it all at last! Yet everyone had had enough, and the youngest Cratchits in particular, were steeped in sage and onion to the eyebrows! But now, the plates being changed by Miss Belinda, Mrs Cratchit left the room alone – too nervous to bear witnesses – to take the pudding up, and bring it in. Suppose it should not be done enough. Suppose it should break in turning out: Suppose somebody should have got over the wall of the back-yard, and stolen it, while they were merry with the goose: a supposition at which the two young Cratchits became livid: all sorts of horrors were supposed. Hallo! a great deal of steam! The pudding was out of the copper. A smell like a washing-day! That was the cloth. A smell like an eatinghouse and a pastry cook’s next door to each other, with a laundress’s next door to that! That was the pudding! In half a minute Mrs Cratchit entered: flushed, but smiling proudly: with the pudding, like a speckled cannon-ball, so hard and firm, blazing. In half of half-a-quartern of ignited brandy, and bedight with Christmas holly stuck into the top, Oh, a wonderful pudding – Bob Cratchit said, and calmly too, that he regarded it as the greatest success achieved by Mrs Cratchit since their marriage. Mrs Cratchit said that now the weight was off her mind, she would confess she had had her doubts about the quantity of flour. Everybody had something to say about it, but nobody said or thought it was at all a small pudding for a large family. It would have been flat heresy to do so. Any Cratchit would have blushed to hint at such a thing.

Bob and Martha Cratchit have somehow ensured that on the pitiful wages he has squeezed out of Scrooge, they have on their table – in reduced form, but still there – what every family in England expected to have on a Christmas Day.

Goose and turkey

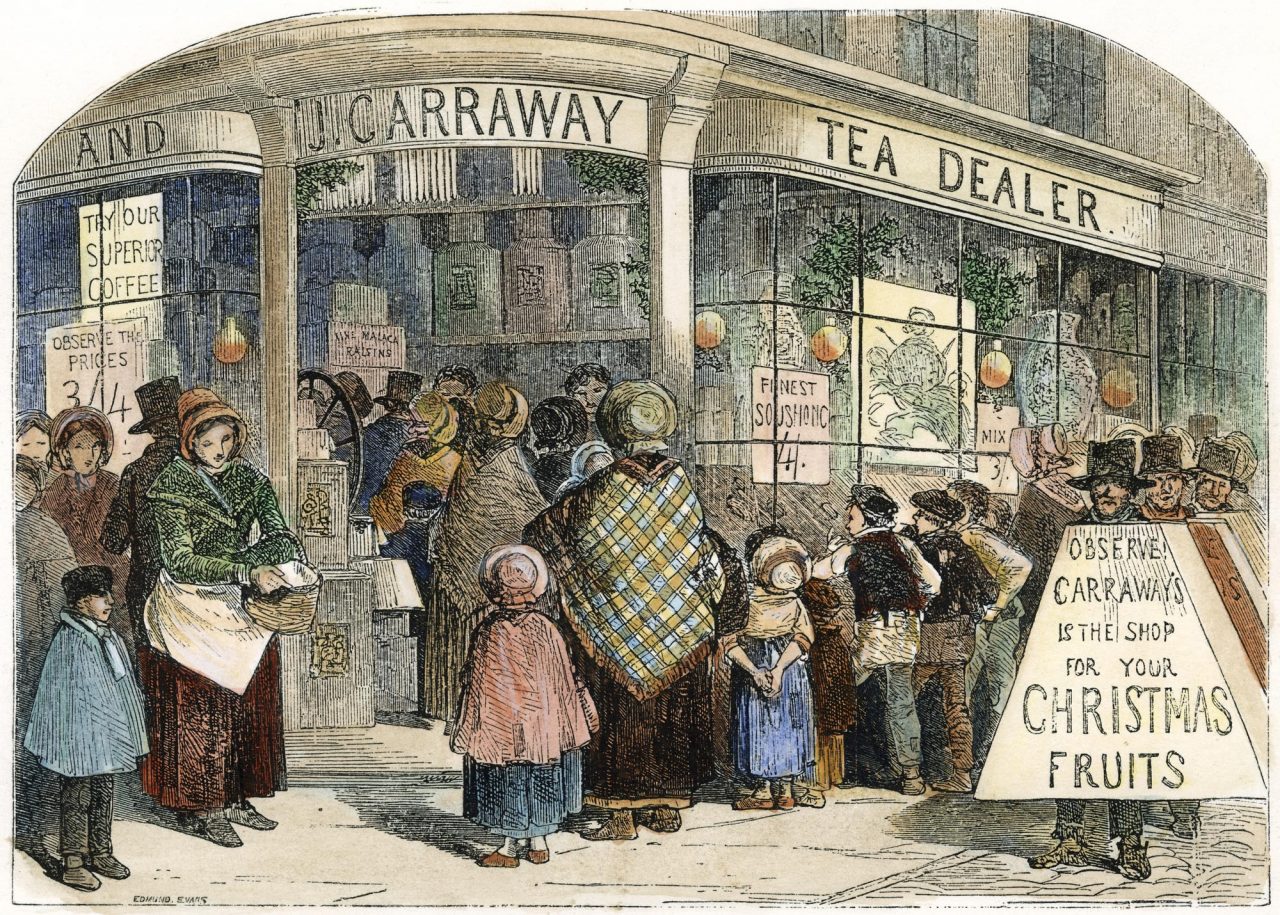

The goose had been established as Christmas fare since the time of Elizabeth I, although it was a luxury only affordable by a poor man if he belonged to a Goose Club, paying in so much a week, and, of course, being cheated along the way. The Temperance Movement waged a war against the consumption of alcohol and took aim at the Goose Clubs, which were often equivalent to pubs and which lured their members into spending their nugatory salaries on the demon drink.

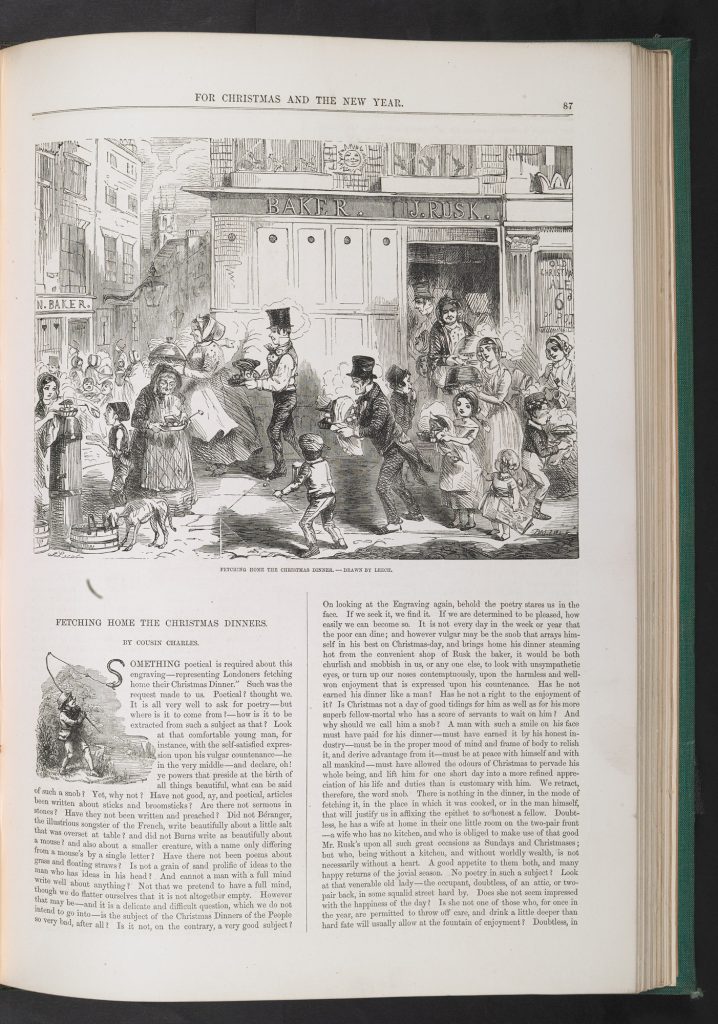

A goose, like the Cratchits’ would be cooked at the bakers; few working-class households had ovens, so the baker, for a small consideration, would leave his alight on Christmas Day. This is where the younger Cratchits go to fetch the goose. Thanks to the influx of poultry from France and Germany in the 1840s, geese became much more readily available.

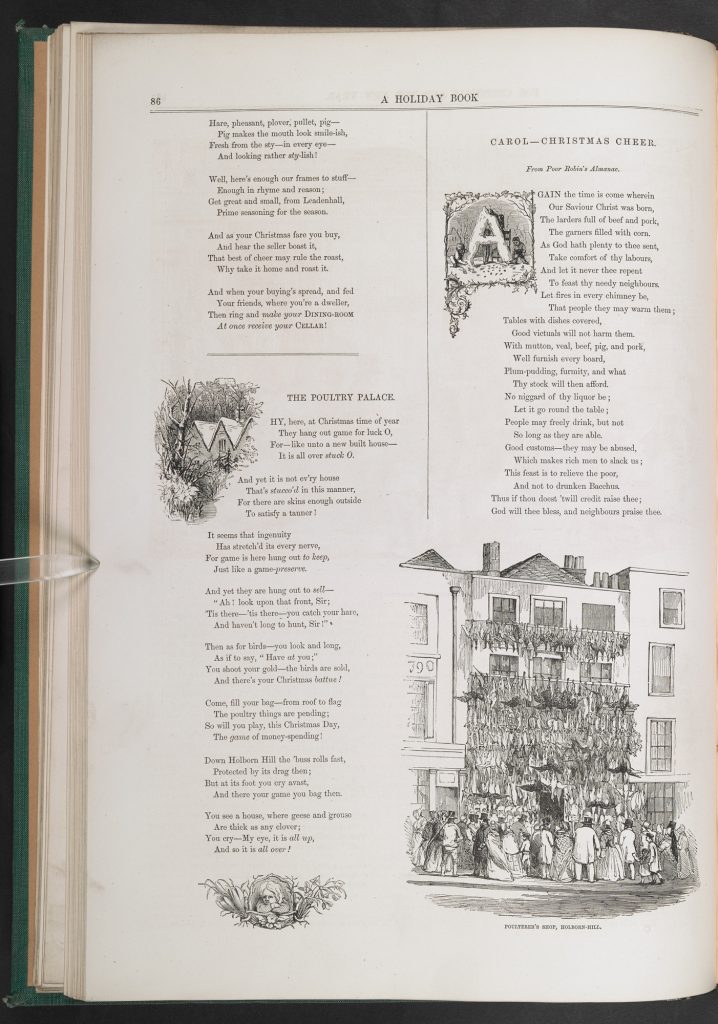

Turkey too, had a long tradition of Christmas consumption – since the 16th century when it was introduced to Europe by the conquistadors – and was being reared in ever greater quantities, mostly in Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridge. It was a considerable task to get turkeys to the metropolis. The birds had to walk, their feet shod or wrapped in rags or coated with tar; the journey down could take weeks. Later, they were slaughtered on the farms and conveyed by coach, a three-day journey; with the development of railways they became more accessible to the general population. The poulterers stayed open on Christmas Day, which is how Scrooge was able to order one in the excitement of his new conversion. In some households – not the Cratchits’, alas – the bird was surmounted by a string of sausages served up in a string; this was called the alderman’s chain.

The Christmas pudding and mince pies

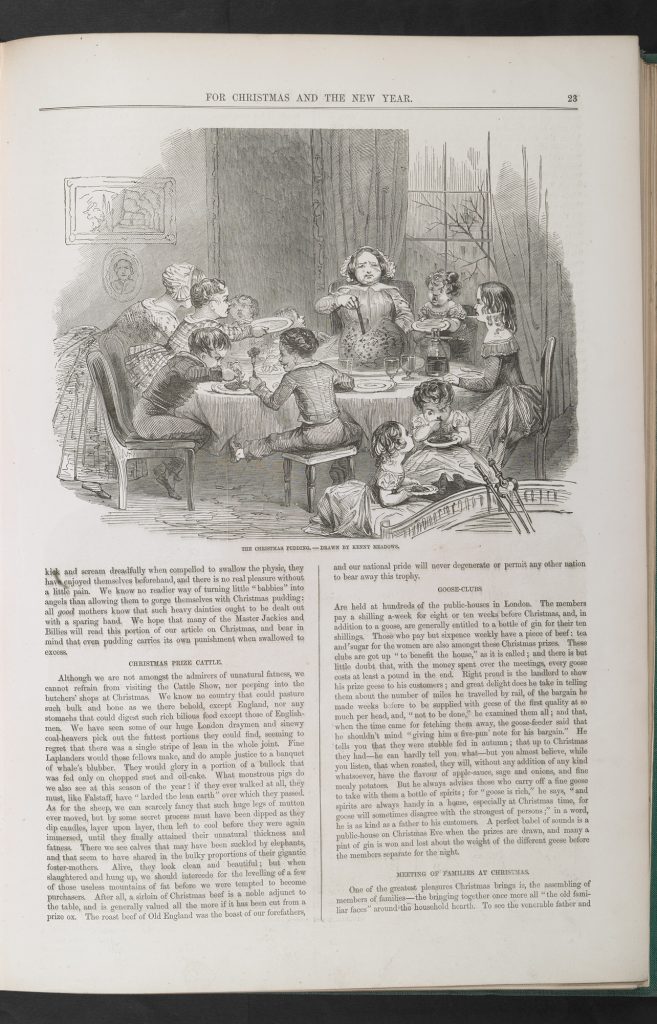

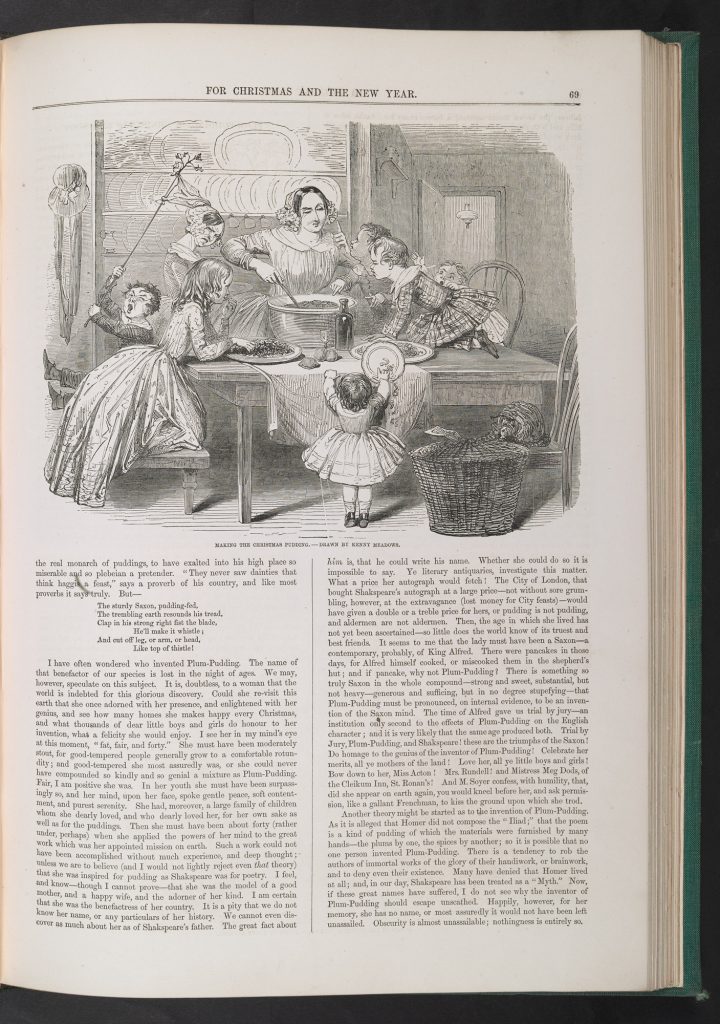

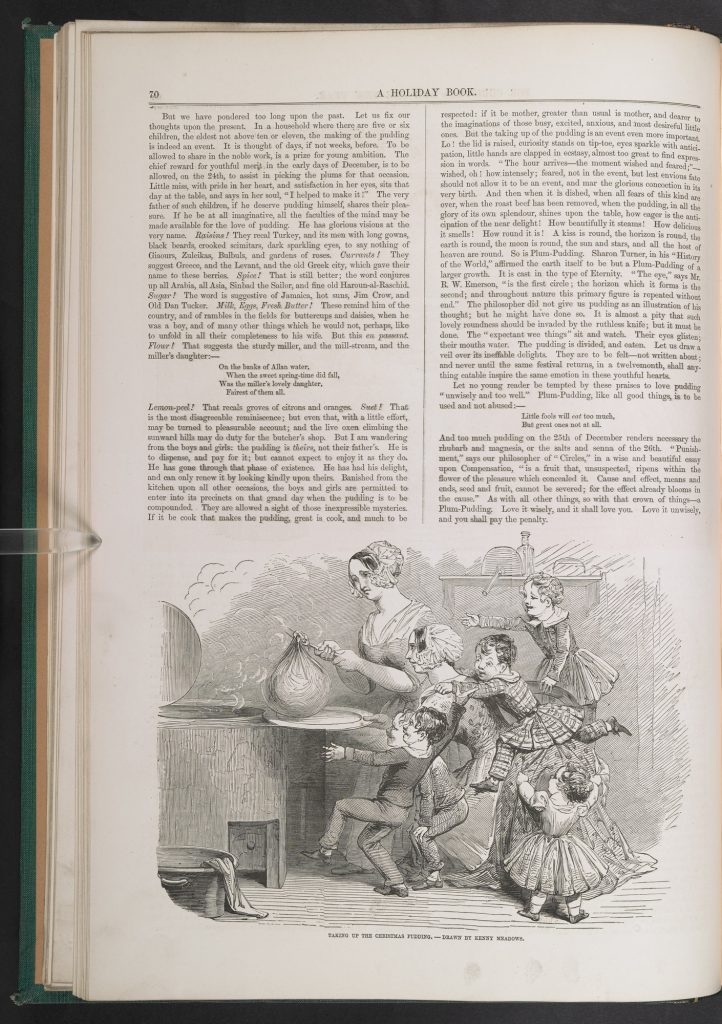

The Christmas pudding, that was such a feature of the Cratchits’ Christmas, was on every menu, and the making of it was a central event of the holiday period. ‘In a household where there are five or six children, the eldest not above ten or eleven, the making of the pudding is indeed an event’, reported the Illustrated London News in 1848:

It is thought of days, if not weeks, before. To be allowed to share in the noble work, is a prize for young ambition… Lo! the lid is raised, curiosity stands on tip-toe, eyes sparkle with anticipation, little hands are clapped in extasy, almost too great to find expression in words. The hour arrives – the moment wished and feared – wished, oh! How intensely; feared, not in the event, but lest envious fate should not allow it to be an event, and mar the glorious Concoction in its very birth. And then when it is dished, when all fears of this kind are over, when the roast beef has been removed, when the pudding, in all the glory of its own splendour, shines upon the table, how eager is the anticipation of the near delight! How beautifully it steams! How delicious it smells! How round it is! A kiss is round, the horizon is round, the earth is round, the moon is round, the sun and stars, and all the host of heaven are round. So is plum pudding.

The same paper regarded British prowess in this area as a matter of patriotic pride: ‘the French have no idea how to make a plum pudding, but some friendly genius instructed the English in the art … the plum pudding symbolises so much English antiquity – English superstition – English enterprise – English generosity – and above all, English taste’.

It was generally regarded as something of a marvel. The Cratchits’ pudding – prepared in their copper washing tub – was accompanied by a wave of excitement:

Hallo! a great deal of steam! The pudding was out of the copper. A smell like a washing-day That was the cloth. A smell like an eating house and a pastry cook’s next door to each other, with a laundress’s next door to that! That was the pudding! In half a minute Mrs Cratchit entered: flushed, but smiling proudly: with the pudding, like a speckled cannon-ball, so hard and firm, blazing. In half of half-a-quartern of ignited brandy, and bedight with Christmas holly stuck into the top, Oh, a wonderful pudding – Bob Cratchit said, and calmly too, that he regarded it as the greatest success achieved by Mrs Cratchit since their marriage. Mrs Cratchit said that now the weight was off her mind, she would confess she had had her doubts about the quantity of flour. Everybody had something to say about it, but nobody said or thought it was at all a small pudding for a large family. It would have been flat heresy to do so. Any Cratchit would have blushed to hint at such a thing.

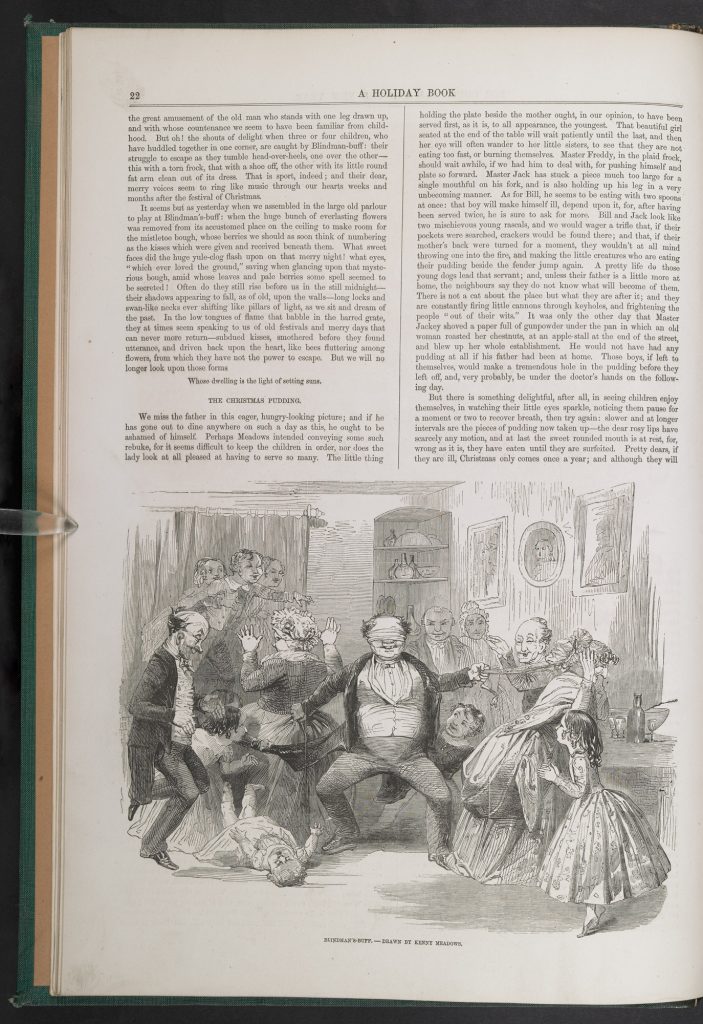

In Boz’s early sketch describing a Christmas dinner, there is a similar level of excitement:

when, at last, a stout servant staggers in with a gigantic pudding, with a sprig of holly in the top, there is such a laughing, and shouting, and clapping of little chubby hands, and kicking up of fat dumpy legs, as can only be equalled by the applause with which the astonishing feat of pouring lighted brandy into mince pies is received by the younger visitors. Then the dessert! And the wine!

Like mince pies, which were originally made with shredded meat, the plum pudding had contained boiled beef and mutton, and was actually a form of frumenty (a thick wheat porridge popular in medieval Europe), containing in addition raisins, currants, prunes, wines and spices. It became plum pudding – plum because of the prunes which were used in its making before the use of raisins – when it was thickened with eggs, breadcrumbs, dried fruit, ale and spirits. The Puritans of course banned it – far too many enjoyable ingredients – and it was not restored till the reign of George I. The Church decreed that puddings should be made on the 25th Sunday after Trinity, and prepared with 13 ingredients to represent Christ and the 12 Apostles; it was to be stirred by every family member in turn from east to west, in honour of the Wise Men and their supposed journey in that direction. Mince pies seem to have had their origin in a representation of Christ’s manger; they were oblong, and in-side was a pastry baby. According to tradition, if one ate a mince pie on each of the 12 days of Christmas, one would have twelve days of happiness, which was, in a sense, what the whole feast was about: enjoying oneself so much that it would last the year until it returned.

Mulled wine

The mulled wine offered immediate gratification. The Cratchits’ was, like everything else at their feast, cheaply made:

Bob, turning up his cuffs – as if, poor fellow, they were capable of being made more shabby – compounded some hot mixture in a jug with gin and lemons, and stirred it round and round and put it on the hob to simmer.

But it is sufficient to its purpose.

At last the dinner was all done, the cloth was cleared, the hearth swept, and the fire made up. The compound in the jug being tasted and considered perfect, apples and oranges were put upon the table, and a shovel-full of chestnuts on the fire. Then all the Cratchit family drew round the hearth, in what Bob Cratchit called a circle, meaning half a one; and at Bob Cratchit’s elbow stood the family display of glass; two tumblers, and a custard-cup without a handle. These held the hot stuff from the jug, however, as well as golden goblets would have done; and Bob served it out with beaming looks, while the chestnuts on the fire sputtered and crackled noisily. Then Bob proposed: ‘A Merry Christmas to us all, my dears. God bless us!’

When Scrooge – who is shortly, if reluctantly, to be toasted by the Cratchits, or at least some of them – in his reformed state wants to sit and talk to Bob about his plans for Bob’s future, he does so over a smoking bishop – which is made by pouring red wine (so much more expensive than the gin which Bob uses) – over bitter oranges and mulling the liquid in a vessel with a long funnel, after which sugar and spices are added. The purple hue resulting from this process gives it its association with bishops.

Rich and poor

Dickens had great faith in the humanising power of the Christmas feast. He was thinking, as always, principally of the poor, and in his next Christmas book he positively attacks the rich, not so much for their wealth as for their indifference to the suffering of others. But the idea of marking Christmas with abundance runs through his writings. Despite David Copperfield’s dismal Christmas dinner with a cowed Joe Gargery and an implacable Mrs Joe, and notwithstanding his setting of the murder in Edwin Drood on Christmas Day, he happily sketches in a scene of Christmas contentment in the story which he read to such powerful sentimental effect, ‘Dr Marigold’. At the climax of the story, the travelling salesman settles into his cart for Christmas:

I had had a first rate autumn of it, and on the twenty-third of December, one thousand eight hundred and sixty-four, I found myself at Uxbridge, Middlesex, clean sold out. So I jogged up to London with the old horse, light and easy, to have my Christmas Eve and Christmas Day alone by the fire in the Library Cart, and then to buy a regular new stock of goods all round, to sell ’em again and get the money. I am a neat hand at cookery, and I’ll tell you that I knocked up for my Christmas Eve dinner in the Library Cart. I knocked up a beefsteak pudding for one, with two kidneys, a dozen oysters, and a couple of mushrooms, thrown in. It’s a pudding to put a man in good humour with everything, except the two bottom buttons of his waistcoat.

It is a serene vignette of the warming power of the Christmas feast, and perfectly sets the scene for the deeply touching resolution which follows it. Thomas Carlyle said of his friend – for whose political and intellectual views he had little time, though he acknowledged his literary genius – ‘his theory of life was entirely wrong. He believed that men should be buttered up, and the world made soft and accommodating for them, and all sorts of fellows should have turkey for Christmas dinner’. Exactly.

© Simon Callow

撰稿人: Simon Callow

Simon Callow was born in London in 1949. He went to Queen’s University in Belfast, but after a year he ran away to become an actor. He trained at the Drama Centre; his first job was at the Edinburgh Festival in 1973. In 1979, he created the part of Mozart in Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus, and later appeared in the movie, playing Emmanuel Schikaneder. He has since appeared in over forty films. He directed his first play in 1984, the year in which his first book, Being an Actor, appeared. His sixteenth book, Charles Dickens and the Great Theatre of the World, appeared in 2012. In 2017 his book Being Wagner: The Triumph of the Will was published.