E M Forster’s A Room with a View

出版日期: 1908 文学时期: 20th Century

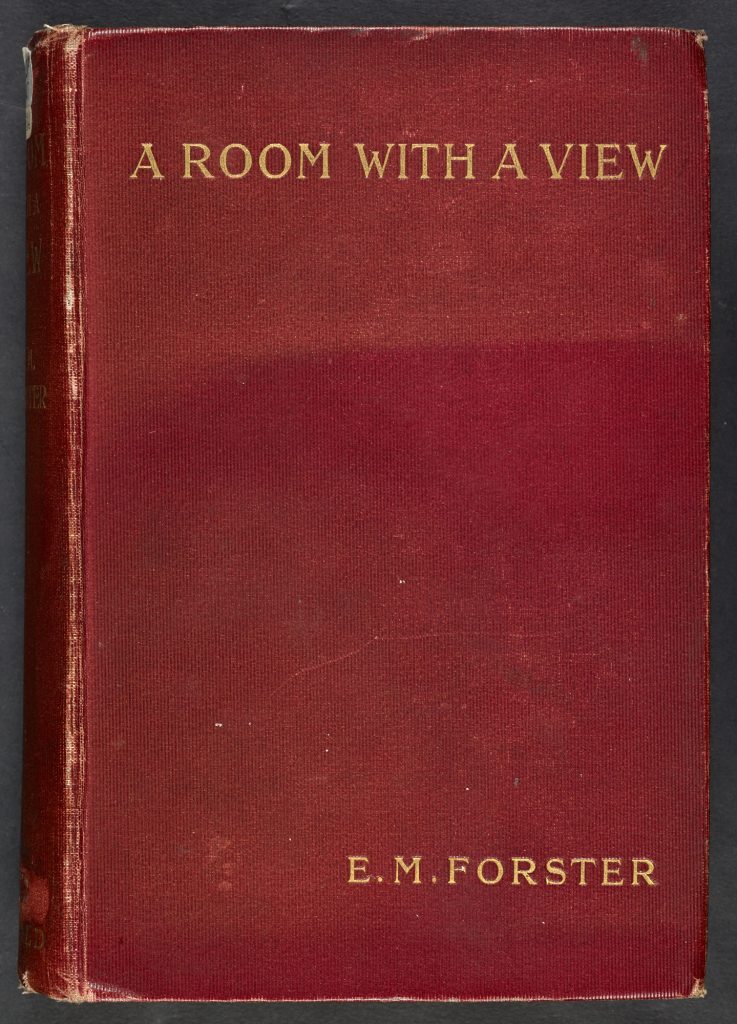

A Room with a View was E M Forster’s third novel after Where Angels Fear to Tread (1905) and The Longest Journey (1907), although he began writing it at least five years before it was first published in 1908. Though Forster forbade adaptations in his lifetime, the novel was made into an award-winning film by the Merchant Ivory company in 1985.

Forster gathered the inspiration for the novel on a trip that he made with his own mother after graduating from King’s College, Cambridge in 1901; the hotel they stayed at was called the Pensione Simi, and Forster began writing the work in Rome and completed it in England. It seems that his character Lucy, like Forster, escapes the boredom of her surroundings by losing herself in playing the piano.

Plot

The title refers to the booking that his characters, Lucy Honeychurch and Charlotte Bartlett, believed they had made at the Pensione Bertolini, Florence.

Forster uses this apparently banal situation to explore the rigidly class-based nature of Edwardian English society: the room’s occupants – Mr Emerson and his son George, who are of lower social standing – politely give it up on the more genteel ladies’ behalf. The situation is dramatically complicated when Lucy witnesses a stabbing and is embraced by George. In response, her cousin and chaperone Miss Bartlett, takes her back to Surrey where Lucy accepts a proposal of marriage from Cecil Vyse. But when the Emersons move to a nearby cottage, Lucy realises that she is in fact in love with George, and the novel ends with Lucy and George’s honeymoon back in the Pensione Bertolini.

The English tourist

The novel is divided into two parts, set in Italy and Britain. It narrates the adventures of the protagonist, Lucy Honeychurch, first as a tourist in Florence and then in Windy Corner, her family home in England.

A Room with a View is a romance that makes use of the convention of the marriage plot, but it is also a comedy parodying British tourism in Italy. Forster had spent one year travelling in Italy between 1901 and 1902, and the people and situations he observed during his visit greatly influenced the novel. Lucy’s visit to Northern Italy references the 18th-century Grand Tour, the trip across southern Europe, which was seen as a necessary way for young gentlemen to complete their education. In Forster’s novel, Lucy and her cousin travel to Florence to see the ‘real Italy’ but stay in a pension decorated in English style and managed by a ‘Signora’ with a cockney accent. “It might be London”, claims a disappointed Lucy on arrival.

What is the role of the Baedeker in A Room with a View?

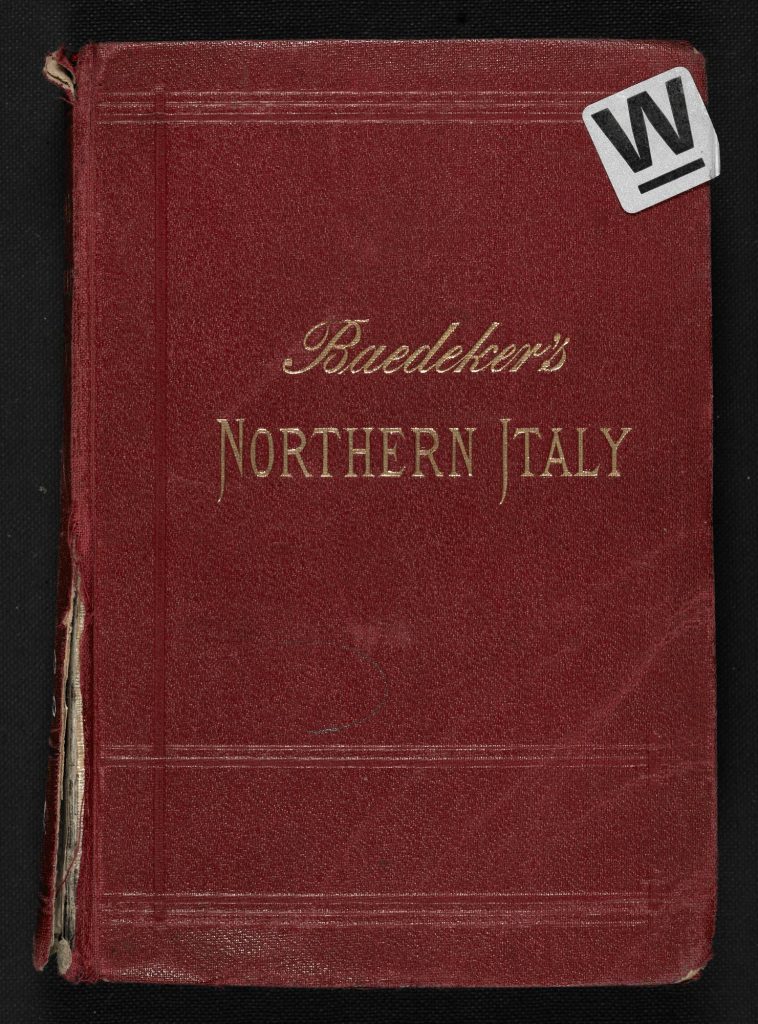

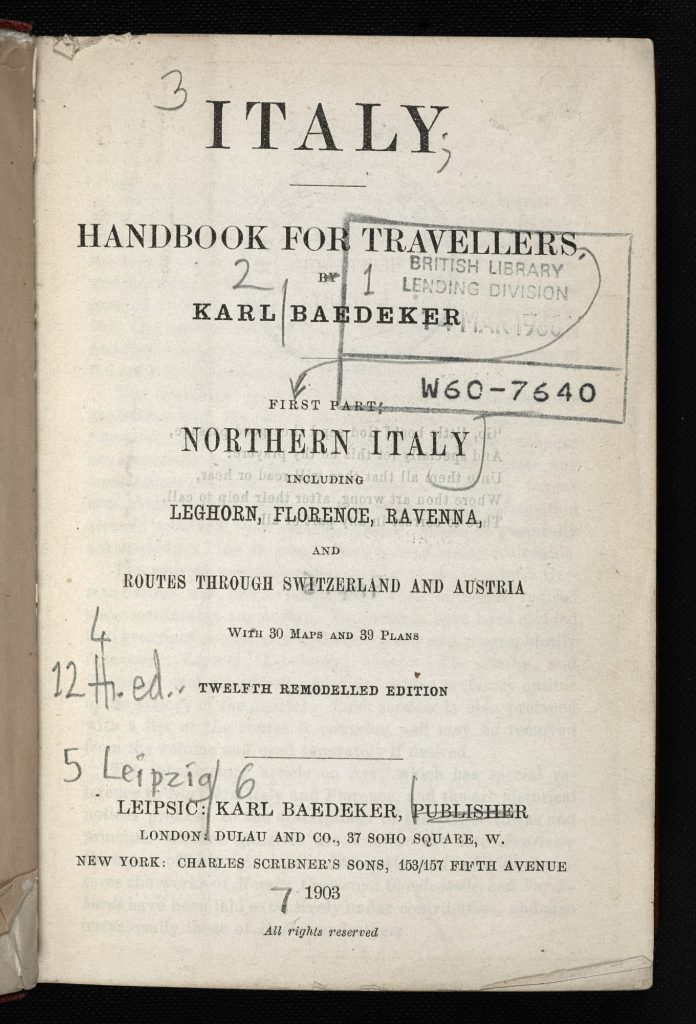

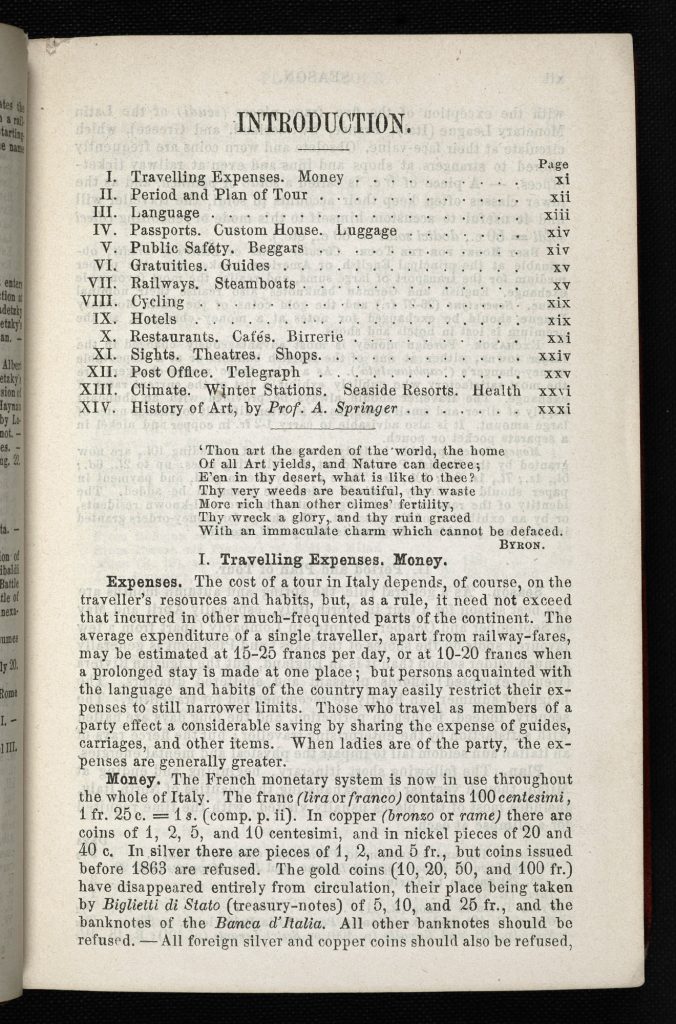

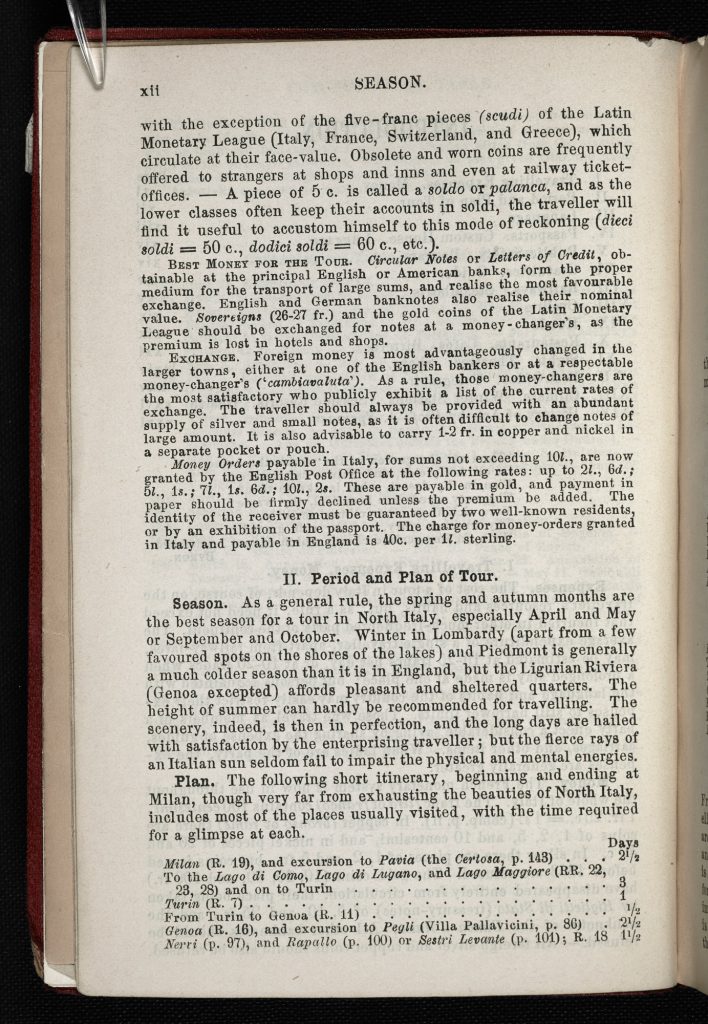

This is the 1903 edition of the Baedeker guidebook to Northern Italy. The publishing firm Baedeker produced some of the most popular portable travel guides of the 19th and early 20th century. The guides contained itineraries, lists of buildings, monuments and museums, and recommendations for accommodation and travel. In many ways these books shaped the modern tourist experience, outlining the places worth visiting and providing summarised accounts of the history and traditions of different countries.

In A Room with a View, the Baedeker is an indispensable possession for the British tourist, allowing him or her to wander around the city independently. At the beginning of the novel, the protagonist, Lucy Honeychurch, memorises Baedeker’s suggested itineraries before visiting Florence. Forster titled Chapter 2 of his novel ‘In Santa Croce with no Baedeker’. In it the unconventional Miss Lavish reprimands Lucy for depending on her guidebook, which she describes as superficial. The real Italy, according to Miss Lavish, could never be understood through a guidebook, but through personal observation. While the vagueness of the idea of ‘real Italy’ is mocked in the novel, it is when Lucy does not carry her guidebook that she gains an alternative explanation of the art in Florence, given by George and his father Mr Emerson.

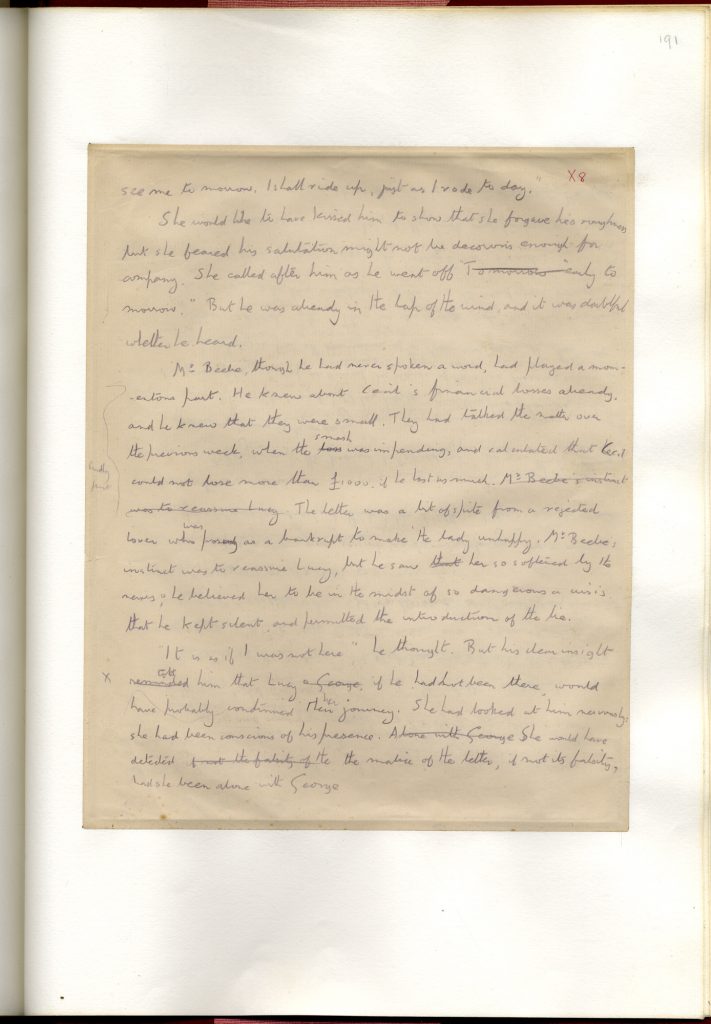

Early draft: an unhappy ending for Lucy and George?

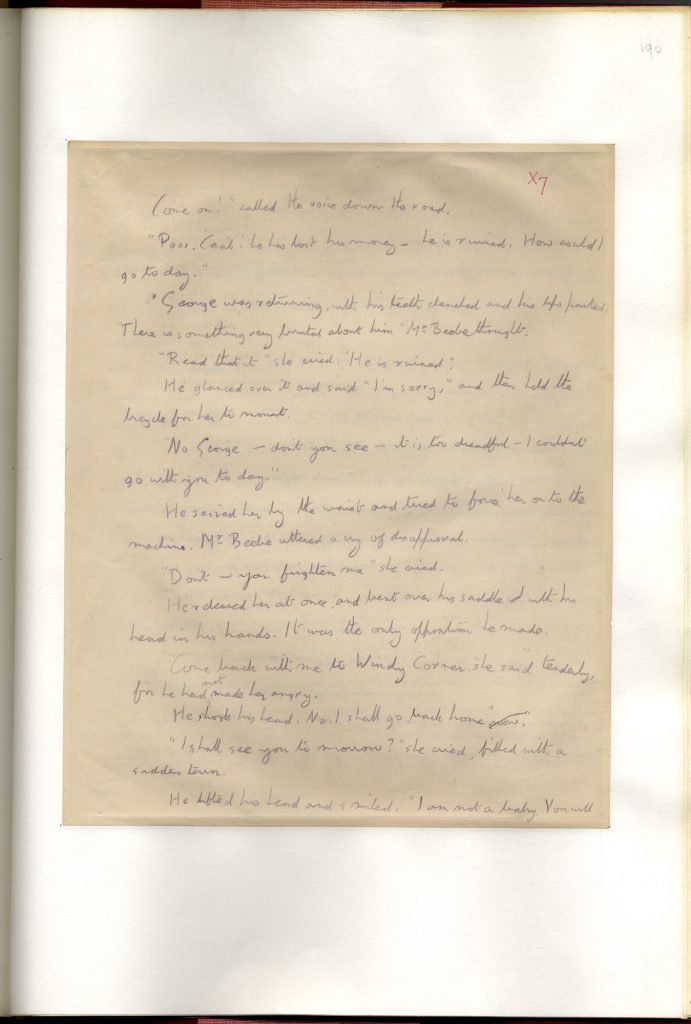

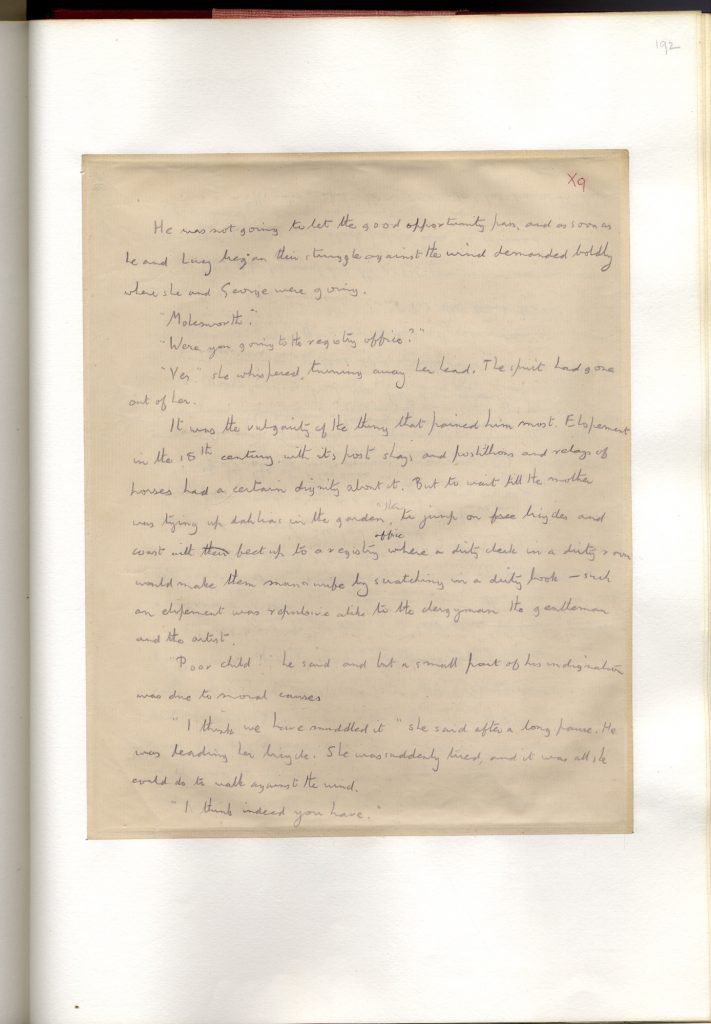

This is an early draft of E M Forster’s novel A Room with a View. The novel was published in 1908, but Forster had begun writing the story at least five years before, creating several versions. He named these drafts the ‘Lucy’ and ‘New Lucy’ novels. These versions differed considerably from the final text of A Room with a View. The ‘Lucy’ draft, for instance, was entirely set in Italy, while in the final version the action was set in both Italy and England, dividing the novel into two clear parts.

This fragment, corresponding to the ‘New Lucy draft’, shows that Forster considered the possibility of a tragic ending for A Room with a View. In this alternative ending George dies in a bicycle accident on the same day that he and Lucy were planning to elope against the wishes of Lucy’s family.

Modernist experimentalism

Despite the somewhat conventional plot, Forster’s writing sits at the intersection between Edwardian realism and modernist experimentalism. Forster was not an avant garde writer in the sense of his modernist contemporaries, but the technical nature of his work demonstrates a more complex interweaving of the traditional and the modern than we might at first recognise. As the critic Santanu Das notes: ‘[Forster’s] complexity lies not in radical experimentation but in something almost more fundamental, more psychological, more transcendental: like Lucy Honeychurch, we are made to “cross” some boundary. There is always something that eludes, unsettles, lingers’. This is what makes Forster’s text, in many ways, so compelling.

Forster’s quiet undermining of Edwardian conventions is coupled with the realisation that the age in which he was writing was on the cusp of enormous social change. In the novel, modernity – that rupture brought about through the clash between the old and the new – is found in the tension between the affirmation of a pastoral England and a deep awareness of its fragility, depicted by Forster in his neat narrative framing of a comedy of manners. Looking back over the catastrophic opening to the twentieth century, Forster wrote in 1939: ‘The pillars of the twenty-thousand-year-old house are crumbling, the human experiment totters, other forms of life watch’. Back in 1908, as the old order is beginning to be dismantled, Forster recognises the beginning of a more ill-defined and fluid social structure.