A Room with a View: class, conventions and the quest for clarity

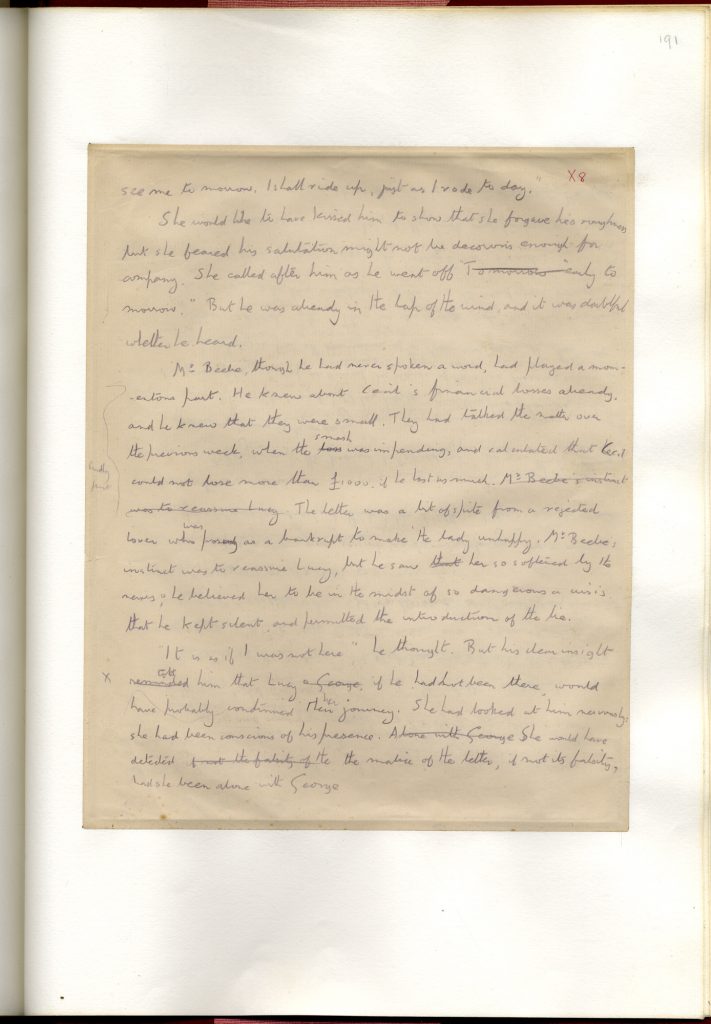

E M Forster started planning A Room with a View in 1902, but it was several years and several drafts before he finished it. Stephanie Forward describes some of the difficulties relating to plot and style that Forster experienced in writing his novel about overcoming conventions in the pursuit of authentic connection.

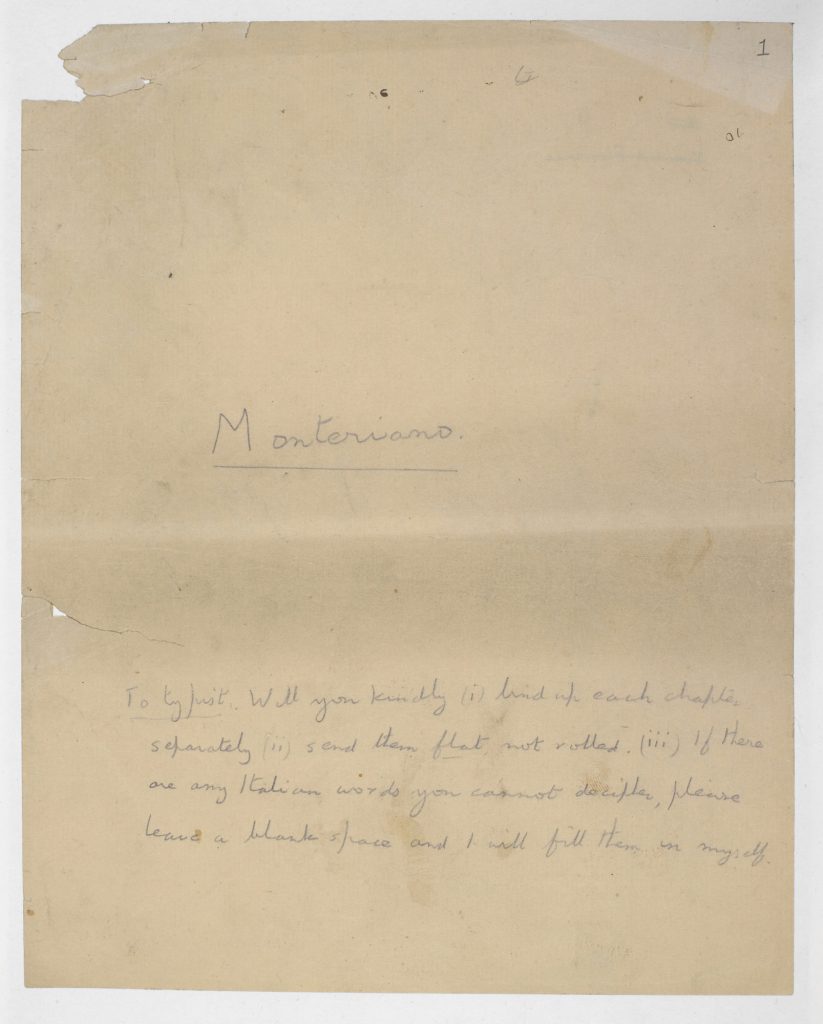

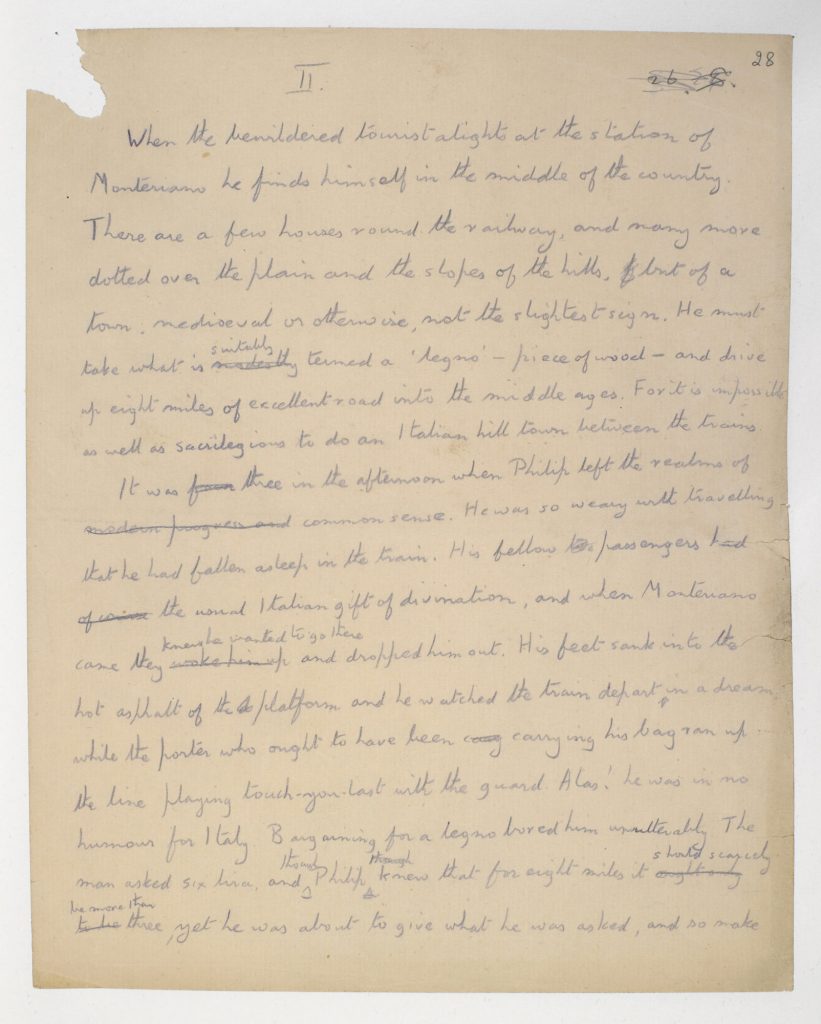

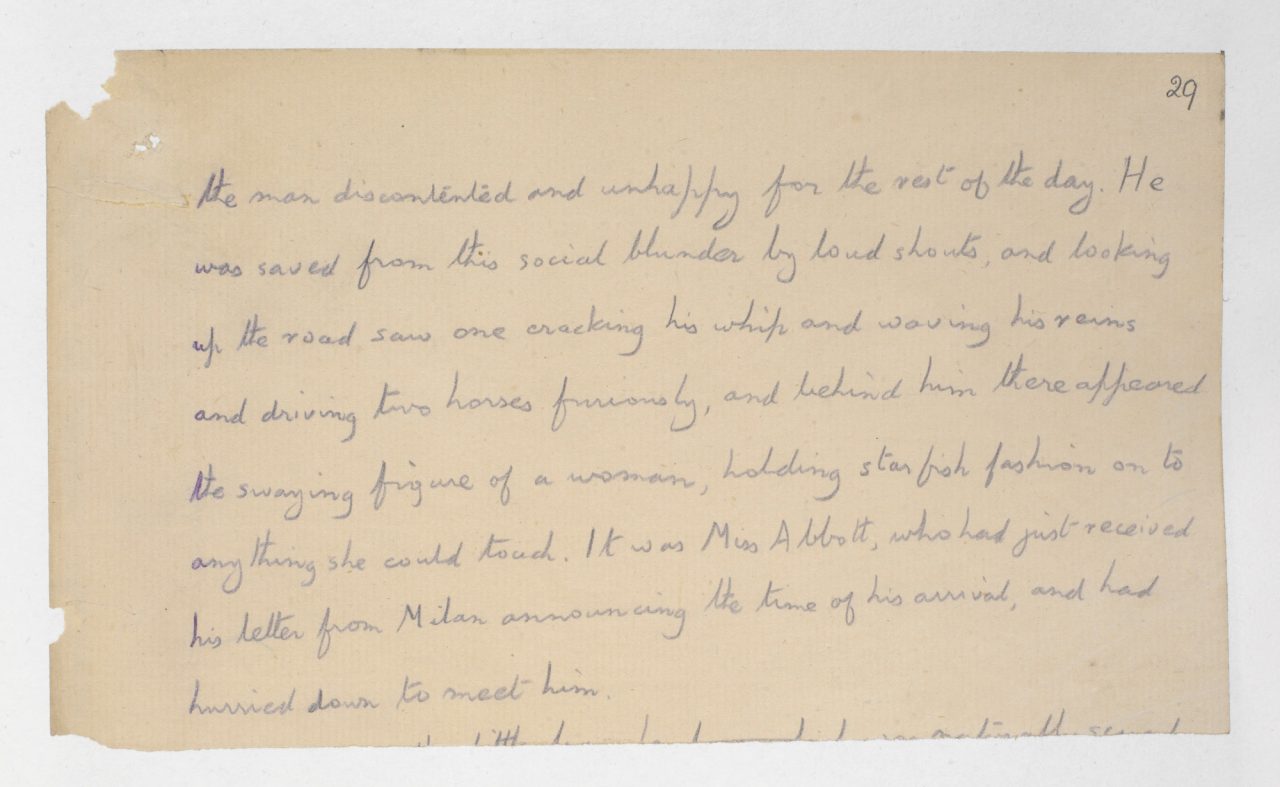

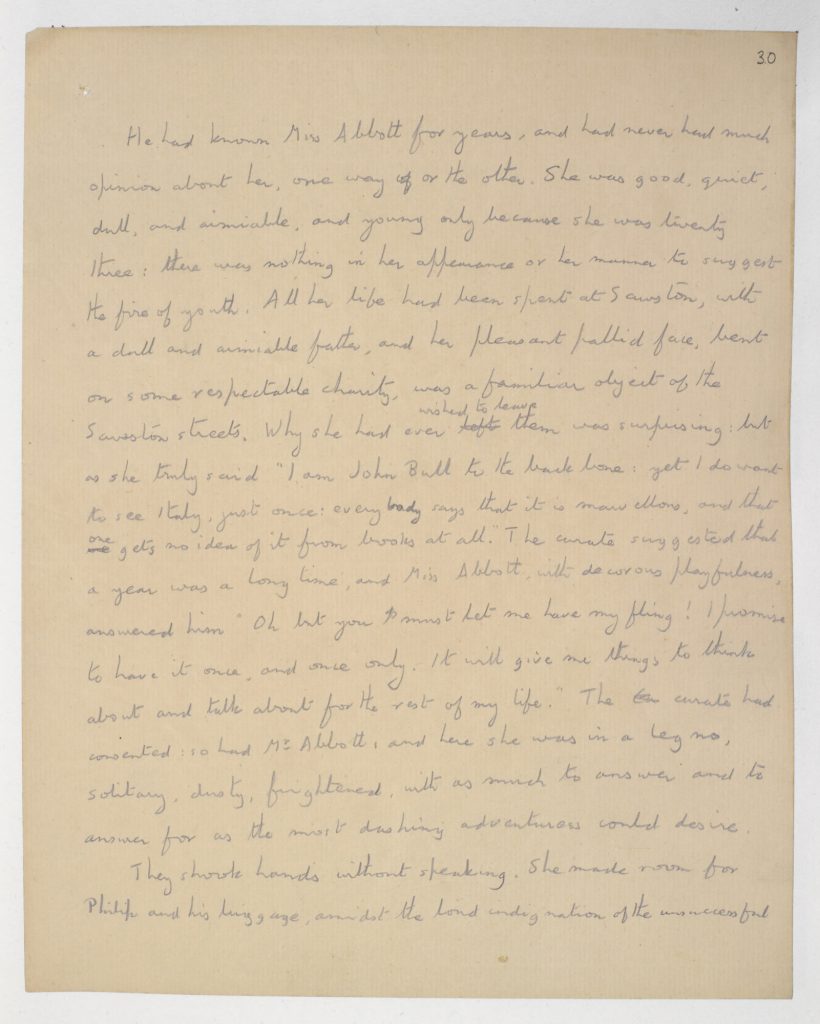

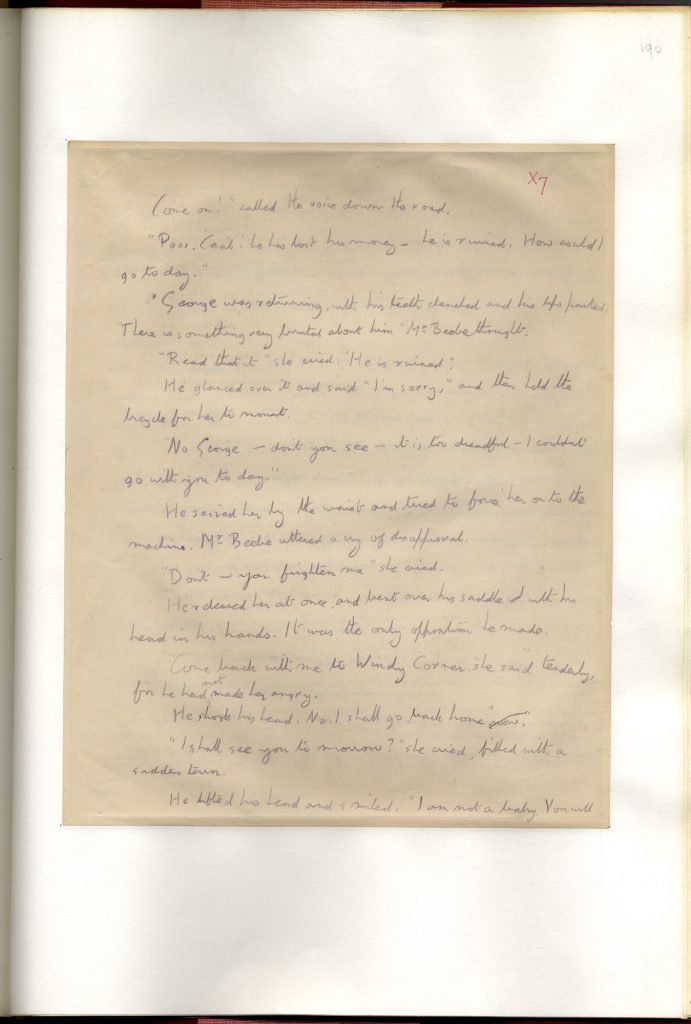

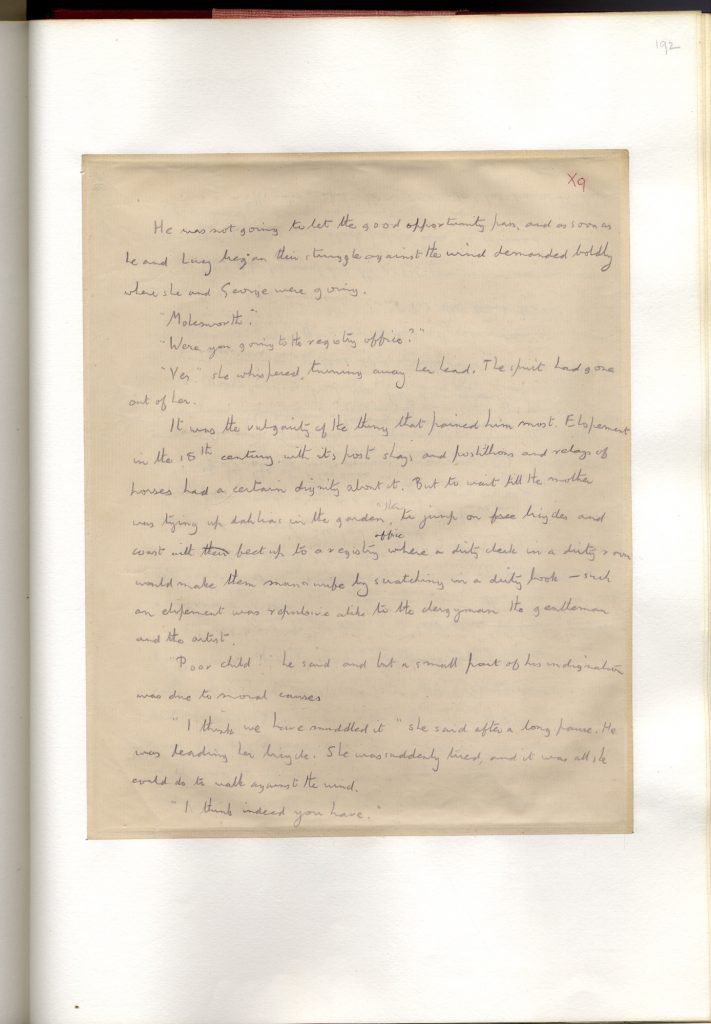

In the winter of 1901–02 E M Forster spent 10 months in Italy, where he devised a novel set in Florence. The list of characters featured Lucy Beringer; her cousin, Miss Bartlett; Miss Lavish and the Misses Alan, and included the enigmatic initials ‘H.O.M.’ Forster persevered with his draft, ‘Old Lucy’, but in December 1903 he suddenly started afresh with ‘The New Lucy Novel’. A year later he set this aside also, to focus on projects that resulted in his first two published novels: Where Angels Fear to Tread (1905) and The Longest Journey (1907). After a bewildering series of versions, A Room with a View eventually came out in 1908 when Forster was 29; it was dedicated to H.O.M.

The lengthy gestation period suggests that the writing process was far from smooth. Forster’s original notebook jottings are held at King’s College, Cambridge, where he commenced four years of study in 1897. One of his closest friends there was a fellow undergraduate, Hugh Owen Meredith (H.O.M.). He was deeply attracted to Meredith and a number of critics have discussed Forster’s sexuality, his suppression of his natural inclinations for many years and the possible impact upon his fiction.[1] Homosexuality was still illegal: indeed, Oscar Wilde had been imprisoned for ‘gross indecency’ as recently as 1895. Meredith was the model for George Emerson: the iconoclastic – and heterosexual – hero of A Room with a View.

Forster was drawn to the utopian values advocated by Edward Carpenter (1844–1929), a socialist philosopher with radical views about equality and sexual tolerance.[2] While Forster’s novel promoted progressive ideals about openness, he was uncomfortably placed in his own private life; consequently, outsiders – those challenging the social conventions of polite society – are a recurring motif in his fiction.

Codes of behaviour

At the outset of A Room with a View Lucy Honeychurch is young and innocent, on the threshold of adult life. As she prepares to emerge into the wider world, Forster’s plot traces her sexual awakening and her growing need to assert her individuality. Arriving in Florence with her chaperone, Miss Bartlett, they encounter the Emersons: a father and son whose behaviour appears to cross the bounds of respectability. When Lucy returns to England she becomes engaged to Cecil Vyse, a supercilious man who does not rouse her passions.

Lucy’s fundamental dilemma is that her instinctive attraction to George Emerson contravenes social ‘rules’. In the text the way to true love is hampered repeatedly by moral scruples and stifling conventions. Forster successfully conveys the stuffiness of upper-middle-class Edwardian society, with its rigid codes of behaviour. In the opening chapter Mr Emerson’s kind offer to swap rooms with the ladies is regarded as a clear breach of decorum. Later, when Miss Bartlett accepts, her determination to observe propriety prompts her to take the larger room. She explains this decision to Lucy: ‘Naturally, of course, I should have given it to you; but I happen to know that it belongs to the young man, and I was sure your mother would not like it’ (ch. 1).

Throughout the book the ideology of the Emersons, their passion for truth and their belief in honesty, means they frequently challenge contemporary mores; Lucy is perturbed by people’s attitudes towards them. Miss Alan is profoundly shocked by the old man’s conversation about his stomach: such references to a part of the body would be regarded as shameful (ch. 3). Lucy presses her seniors for elucidation: ‘old Mr Emerson, is he nice or not nice?’ Her query is highly significant: ‘nice’ did not simply mean ‘pleasant’ and ‘agreeable’; it also meant ‘respectable’ (ch. 5). Class snobbery comes to the fore when Mr Eager reports that Mr Emerson was a labourer’s son, who became a mechanic and then a journalist. Charlotte Bartlett questions George about his profession, deploring his vague response – ‘the railway’ – as ‘a dreadful answer’ (ch. 6). She asserts: ‘There is no need to call him a wicked young man, but obviously he is thoroughly unrefined’ (ch. 7). In Chapter 10 Mrs Honeychurch asks her son, Freddie, about the Emersons, stressing: ‘there is a right sort and a wrong sort, and it’s affectation to pretend there isn’t.’

For his part, Mr Emerson despises cant and hypocrisy. He encourages Lucy to think for herself: to appreciate nature, beauty and passion rather than fretting about the possible violation of social taboos. In Chapter 1 he is eager to give her access to a room with a view, and Forster skilfully develops this as a metaphor. Gradually Lucy absorbs the Emersons’ convictions. A significant moment occurs in Chapter 15 when she asks George if he likes the view of the Weald, and he responds: ‘My father … says that there is only one perfect view – the view of the sky straight over our heads, and that all these views on earth are but bungled copies of it’.

Fluctuating emotions

At different stages of the plot Lucy experiences fluctuating emotions and does not know how to resolve her confusion. It is apparent that Forster’s feelings also oscillated as he wrote. He was sometimes disparaging about his novel, dismissing it in diary entries and letters of 1907–08 as ‘thin’, ‘toshy’, ‘bilge’, ‘slight, unambitious, and uninteresting’; yet he also noted: ‘the characters seem more alive to me than any others I have put together’. Many years later, in his commonplace book of May 1958 he ventured to admit to ‘caring for’ Lucy.

There is evidence that he was particularly anxious about the dénouement. He told his friend R C Trevelyan: ‘It’s bright and merry and I like the story. Yet I wouldn’t and couldn’t finish it in the same style … The question is akin to morality.’[3] Forster’s phrasing here is fascinating: he speaks of tone and style, then suddenly switches the focus to ethics.[4] On 1 December 1906 he had presented a paper on ‘Pessimism in Literature’, in which he considered the thorny problem faced by authors. He was acutely conscious that many readers expected a felicitous outcome, usually marriage; however, this did not sit comfortably with his instinct that simplistic, joyful resolutions were not realistic and were somehow immoral. Pages from an earlier draft of the novel describe George’s demise, with a very different ending from the one Forster used ultimately. His qualms about his choice are demonstrated in a letter he wrote as he penned the final version: ‘Oh Mercy to myself I cried if Lucy didn’t wed’.

Questions have been raised about Forster’s ability to produce satisfying endings to his books. In a journal entry of May 1917 his contemporary Katherine Mansfield did not mince her words when she voiced her frustration about this aspect of his writing: ‘E M Forster never gets any further than warming the teapot. He’s a rare fine hand at that. Feel this teapot. Is it not beautifully warm? Yes, but there ain’t going to be no tea.’[5]

‘something that eludes, unsettles, lingers’

In truth it is difficult to ‘pigeonhole’ Forster as a novelist, and critics have deliberated about his place within modernism. Elements of modernist texts often involved stylistic inventiveness; engagement with proscribed subject matter; a lack of omniscience and moral judgement; a fascination with enigma and the unknown; open endings with a deliberate lack of narrative closure; and the evocation of alienating urban settings. Forster seems to have been poised somewhere between 19th-century realism and modernist experimentation. This problematic position was all too apparent to him and caused him a degree of consternation about his efforts and achievements. A range of literary styles can be identified in his work: for example, there are echoes of Jane Austen’s irony in passages where Forster expresses himself with a delightfully deft satirical touch. On the other hand, there is often a sense of something additional that cannot be pinned down; a tension that alerts us to the author’s elusiveness. As Santanu Das has written: ‘[Forster’s] complexity lies not in radical experimentation but in something almost more fundamental, more psychological, more transcendental: like Lucy Honeychurch, we are made to “cross” some boundary. There is always something that eludes, unsettles, lingers’. [6]

A Room with a View contains a series of striking contrasts, including: convention and passion; darkness and light; blindness and vision; muddle and clarity; and rooms as opposed to views. These oppositions highlight Lucy’s quandaries, as she is torn between distinct attitudes to life and alternative courses of action. A key motif is the idea of ‘muddle’. Avtar Singh points out that muddle is ‘a recurrent expression of rich and varied connotations in Forster’s fiction that normally signifies some fatal obscuring of inner vision by the falsifying conventions of society’.[7] Early in the text Mr Emerson warns Lucy: ‘You are inclined to get muddled … Let yourself go. Pull out from the depths those thoughts that you do not understand, and spread them out in the sunlight and know the meaning of them’ (ch. 2). He explains that George is beset with anxieties of his own about life, and urges Lucy to assist him through his inner conflicts to a sense of peace and joy: ‘Make him realize that by the side of the everlasting Why there is a Yes – a transitory Yes if you like, but a Yes’. In Chapter 19 Mr Emerson pleads with her to believe him:

‘there’s nothing worse than a muddle in all the world. It is easy to face Death and Fate … It is on my muddles that I look back with horror.’

…

‘You can transmute love, ignore it, muddle it, but you can never pull it out of you. I know by experience that the poets are right: love is eternal.’

In later years Lucy is grateful to Mr Emerson for intervening and showing her ‘the holiness of direct desire’; for making her see ‘the whole of everything at once’ (ch. 19). Yet it is worth keeping in mind the old man’s revealing observation in the penultimate chapter: ‘We can help one another but little. I used to think I could teach young people the whole of life, but I know better now, and all my teaching of George has come down to this: beware of muddle.’ Forster’s personal experience and situation certainly made him wary of ideal solutions and unambiguously happy endings.

脚注

- See, for example, Wendy Moffat, A Great Unrecorded History: A New Life of E M Forster (London: Bloomsbury, 2010).

- Tony Brown, ‘Edward Carpenter, Forster and the Evolution of A Room with a View’, English Literature in Transition, 1880–1920, 30 (1987), pp. 279–301. In his introduction to the Penguin Classics edition of A Room with a View, Malcolm Bradbury suggests that old Mr Emerson was created in Carpenter’s image.

- Letter from Forster to Trevelyan, 11 June 1907.

- This dilemma is examined by Zadie Smith in the Guardian, 1 November 2003, in an article based on her Orange Word Lecture: ‘E M Forster’s Ethical Style: Love, Failure and the Good in Fiction’, delivered at the Gielgud Theatre in London on 22 October 2003.

- The Journal of Katherine Mansfield, ed. by John Middleton Murray (London: Constable, 1927), p. 69.

- Santanu Das in The Cambridge Companion to English Novelists, ed. by Adrian Poole (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), p. 346.

- Avtar Singh in The Novels of E M Forster (Atlantic Publishers and Distributors, 1986), p. 99.

Banner credit: AllStar Picture Library / Goldcrest Films

撰稿人: Stephanie Forward

Dr Stephanie Forward is a lecturer, specializing in English Literature. She has been involved in two important collaborative projects between the Open University and the BBC: The Big Read, and the television series The Romantics, and was a contributor to the British Library’s Discovering Literature: Romantics and Victorians site and to the 20th century site. Stephanie has an extensive publications record. She also edited the anthology Dreams, Visions and Realities; co-edited (with Ann Heilmann) Sex, Social Purity and Sarah Grand, and penned the script for the C.D. Blenheim Palace: The Churchills and their Palace.