It was by pure serendipity that I came upon the collection of letters that detailed a hitherto little-known relationship between Virginia Woolf and Ling Shuhua, both part of important avant-garde literary communities in England and China. I was at a Sotheby’s literary auction in London in 1991 perusing the materials for sale, and was taken aback to discover a cache of letters advertised as:

363. Woolf (Virginia) and the Bloomsbury Group. Collection of Papers of the Artist Su Hua Ling Chen [Ling Shuhua], including series of letters to her by Julian Bell, Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell, Vita Sackville-West and others.

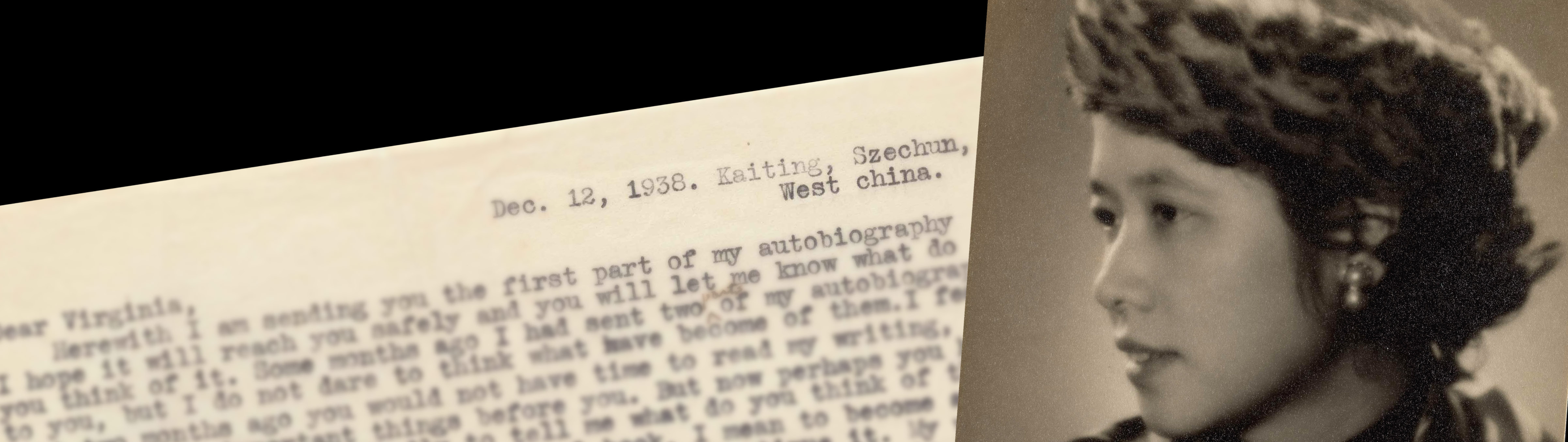

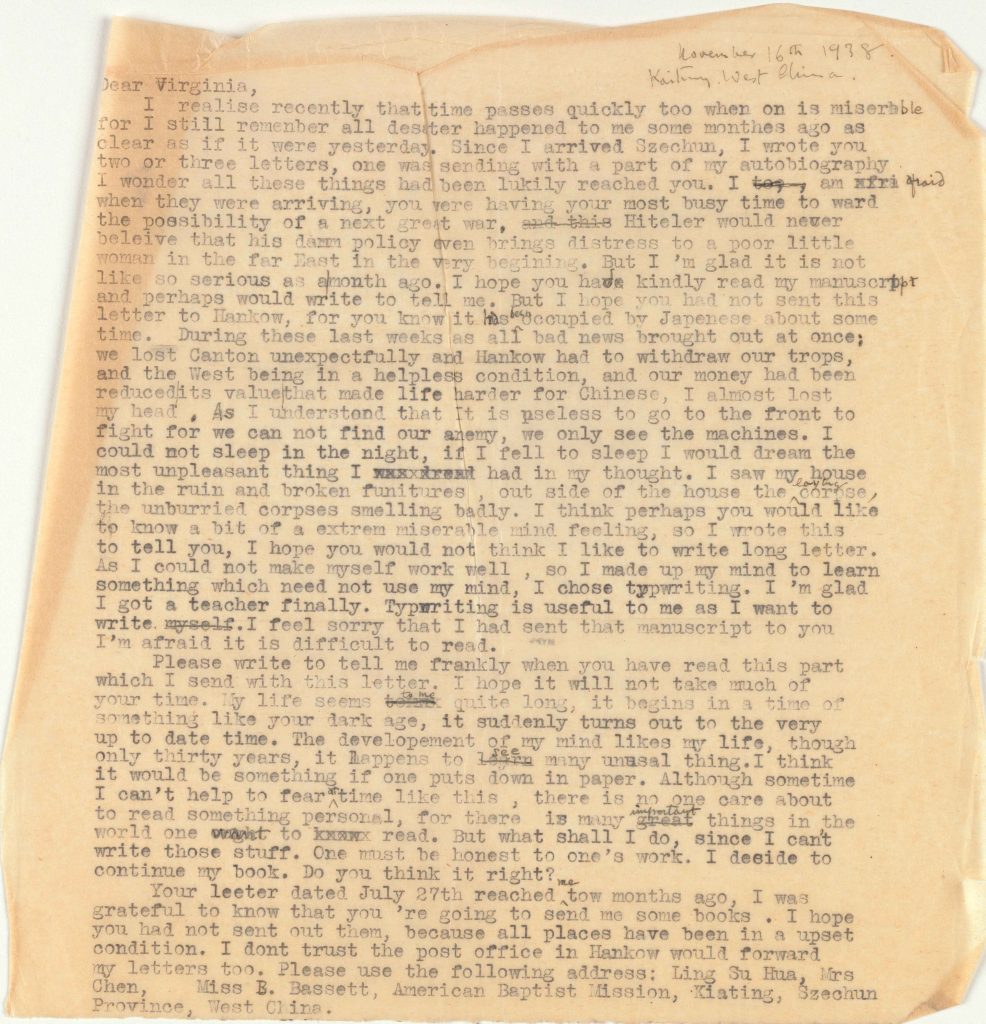

标题:Letter from Ling Shuhua to Virginia Woolf, 24 July 1938

作者/创作者:Ling Shuhua

藏品存于:New York Public Library

版权:© Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations / With kind permission from the Estate of Shuhua Ling

标题:Letter from Ling Shuhua to Virginia Woolf, 24 July 1938

作者/创作者:Ling Shuhua

藏品存于:New York Public Library

版权:© Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations / With kind permission from the Estate of Shuhua Ling

<前页

后页>

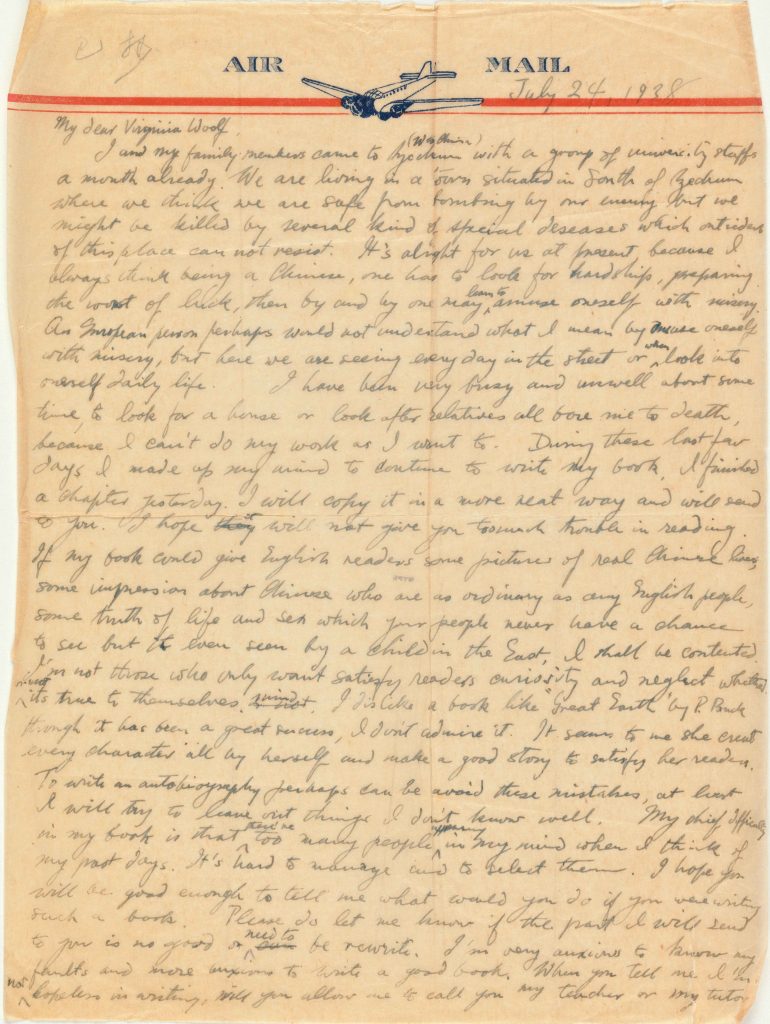

I had never heard of Ling before this, but these letters introduced her as a new part of the Bloomsbury constellation of writers and artists. I learned that she was a talented painter and writer, a mandarin who attended the wedding in 1922 of the Last Emperor Pu Yi, and a member of the literary Crescent Moon group. She entered the Bloomsbury circle through her relationship with Julian Bell, the nephew of Virginia Woolf and son of Vanessa Bell. They first met sometime between 1935 and 1937, when Julian was a visiting professor of English at the National Wuhan University in Hankow (south-east China, Wuhan) teaching Shakespeare, literary composition and the work of the Bloomsbury authors. The letters reveal that Julian had a love affair with Ling (who was married to the eminent Dean Chen, who had hired Bell), before he went off to the Spanish Civil War, where he died in 1937. [1]

标题:Portrait of Shuhua Ling

藏品存于:New York Public Library

版权:© Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations / With kind permission from the Estate of Shuhua Ling

标题:Portrait of Shuhua Ling

藏品存于:New York Public Library

版权:© Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations / With kind permission from the Estate of Shuhua Ling

<前页

后页>

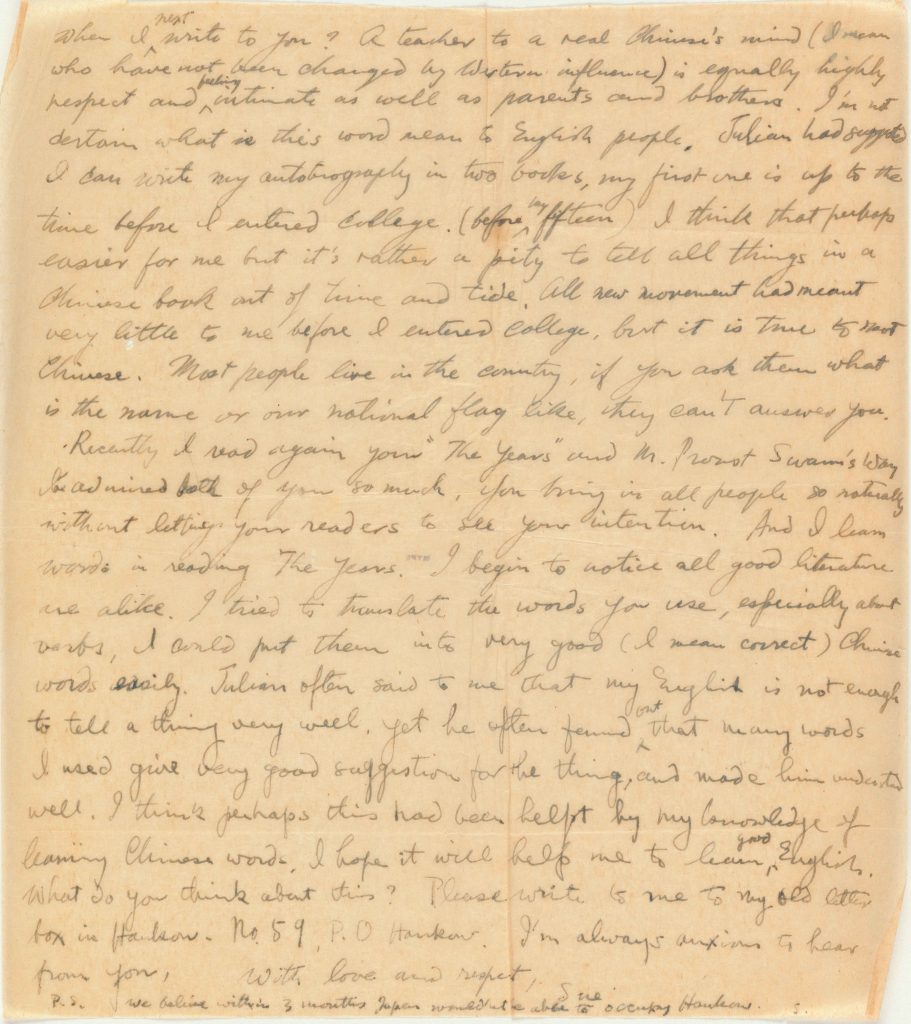

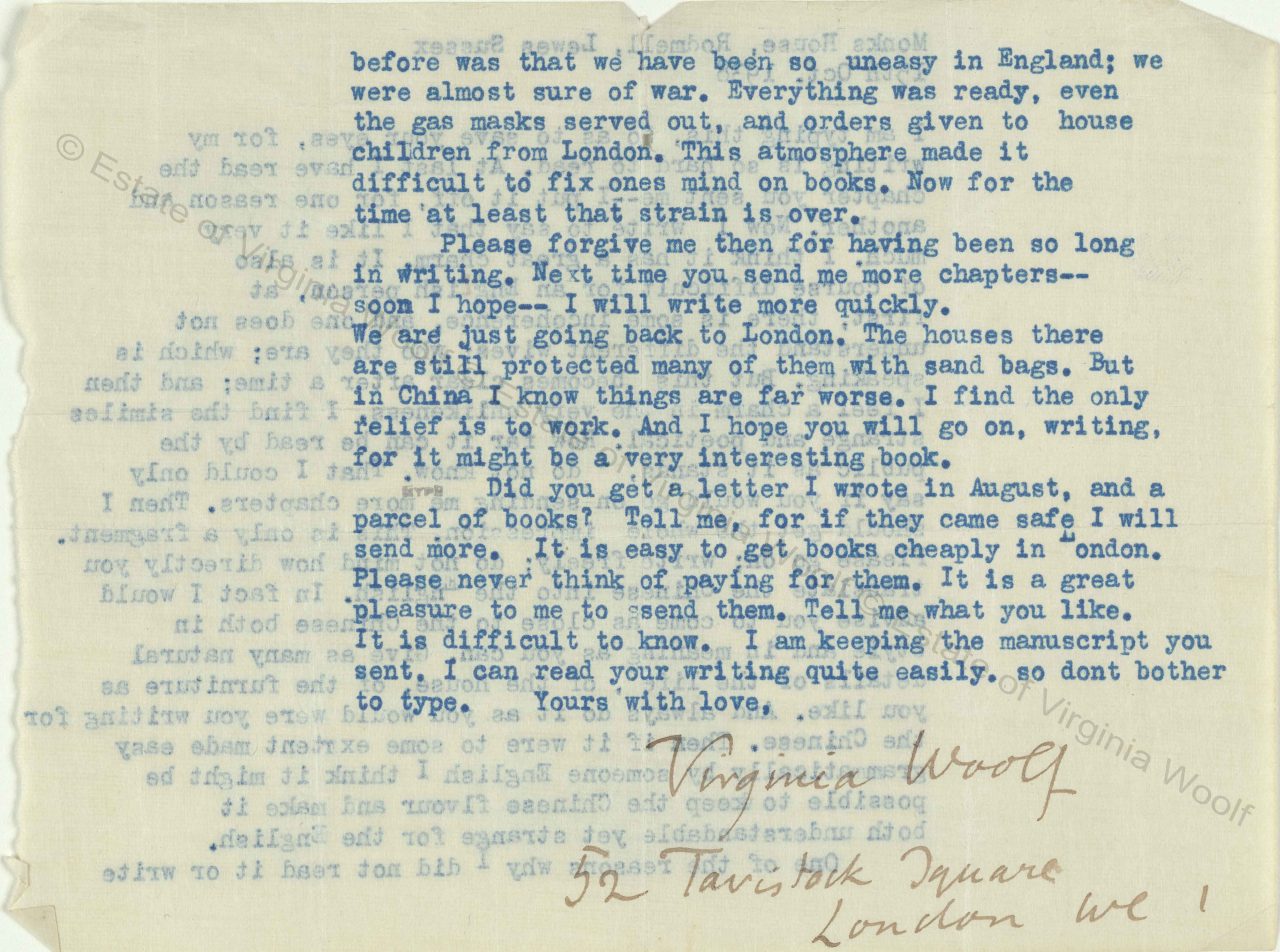

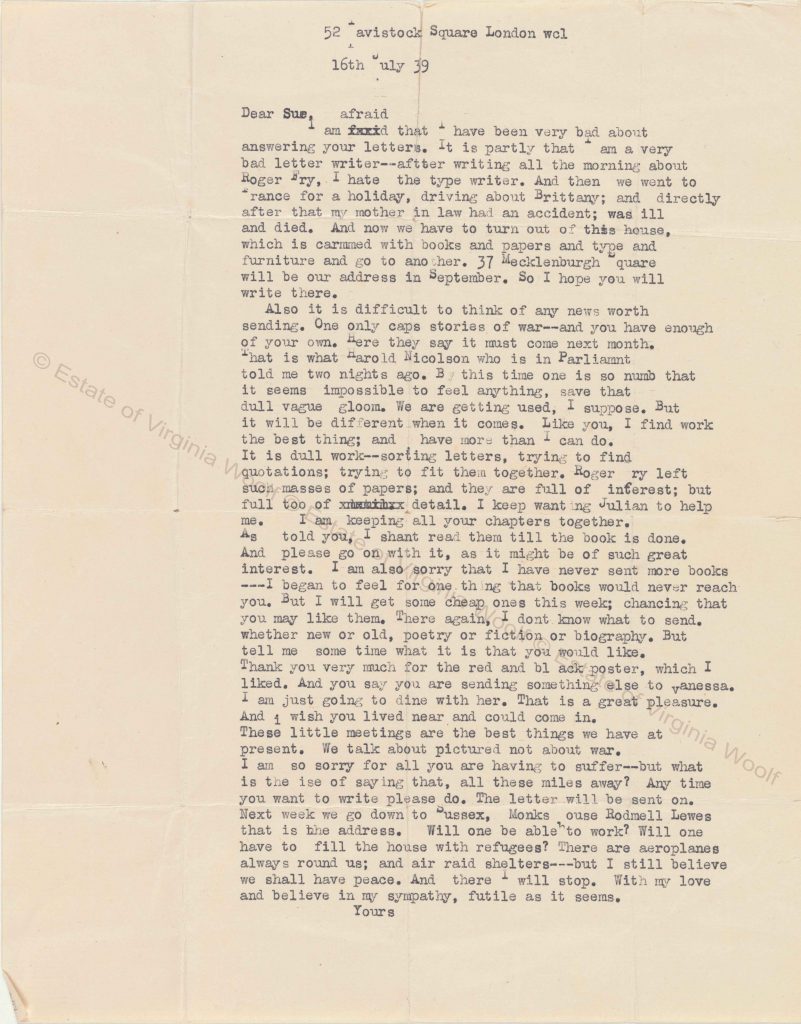

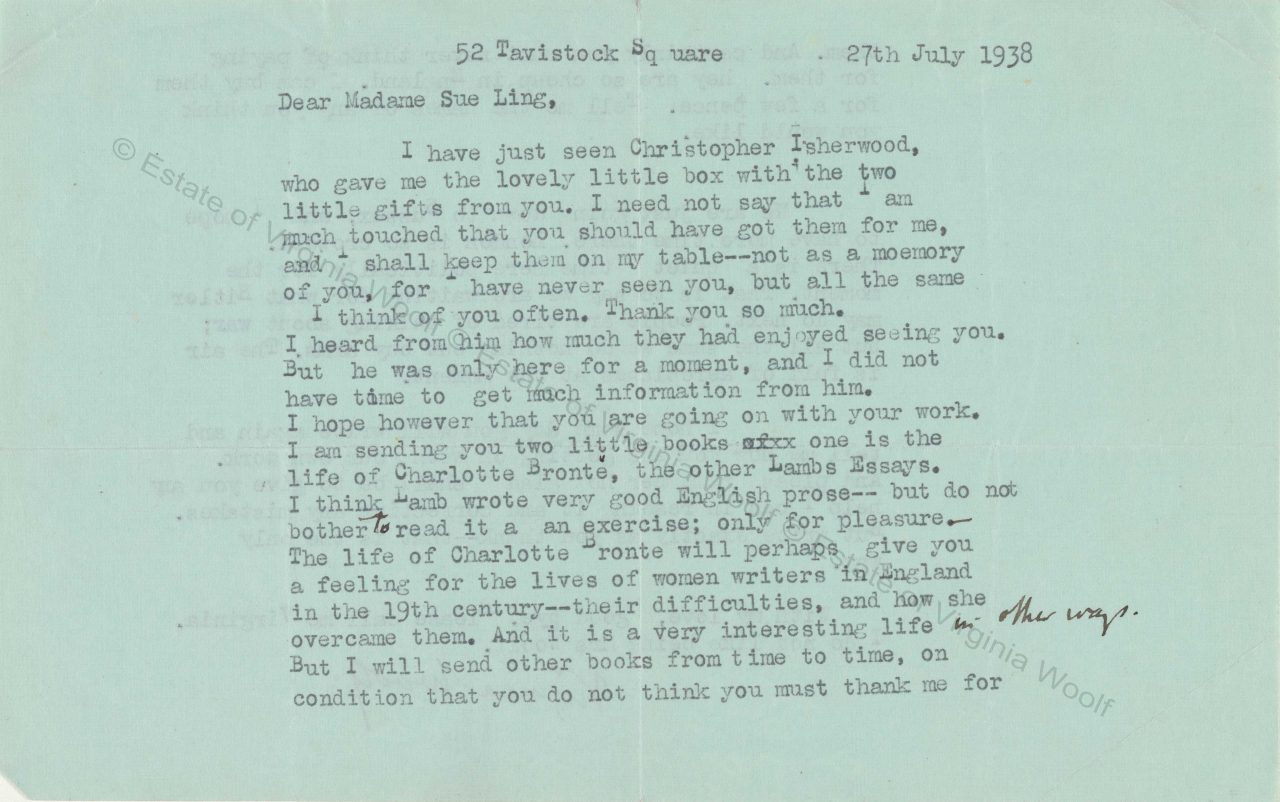

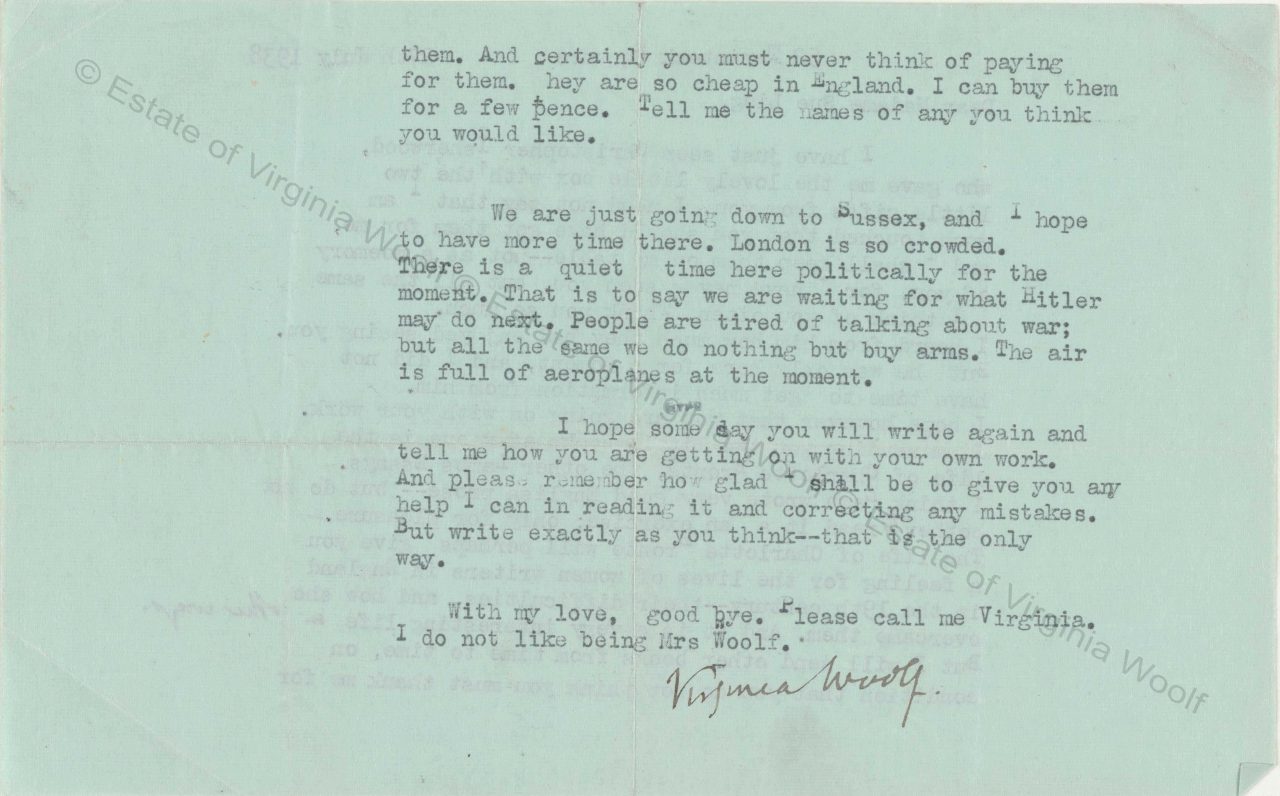

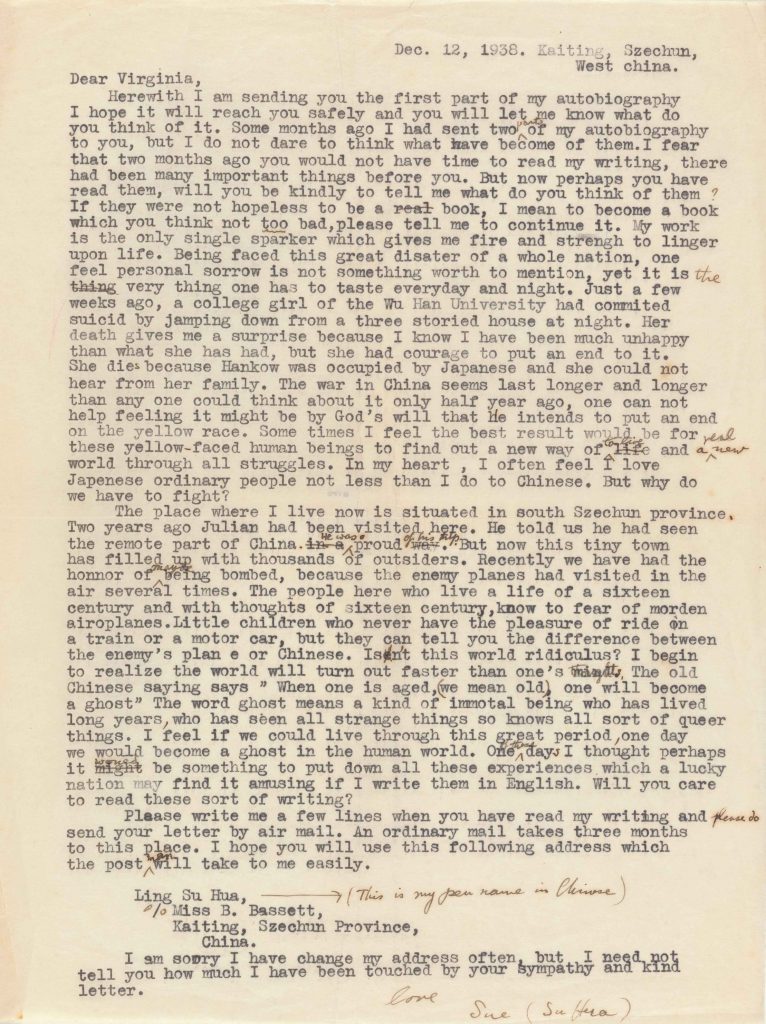

Virginia Woolf began her correspondence with Ling after Julian Bell’s death. They both suffered from personal sorrow over Julian, a vibrant young man of just 29, and his family was responsive to a letter he had written requesting that they connect with and help his friends in the event of his death. In her first letter to Woolf, Ling wrote, ‘beside the general disaster, I have my personal deep sorrow which I never can get out of my mind’. There is a lyric quality in their correspondence (which covers the period 3 March 1938 to 16 July 1939), as each walks across a personal and national bridge. For Woolf and Ling not only connected in sorrow, but also as writers and women struggling in their respective countries, sharing a ‘miserable mind feeling’ during a time of war. Ling was fleeing the Japanese bombing in China, and Woolf wrote that the English were uneasy coming close to being sure of war. ‘Everything was ready’, she said, ‘even the gas masks served out, and orders given to house children from London. This atmosphere made it difficult to fix one’s mind on books’. [2]

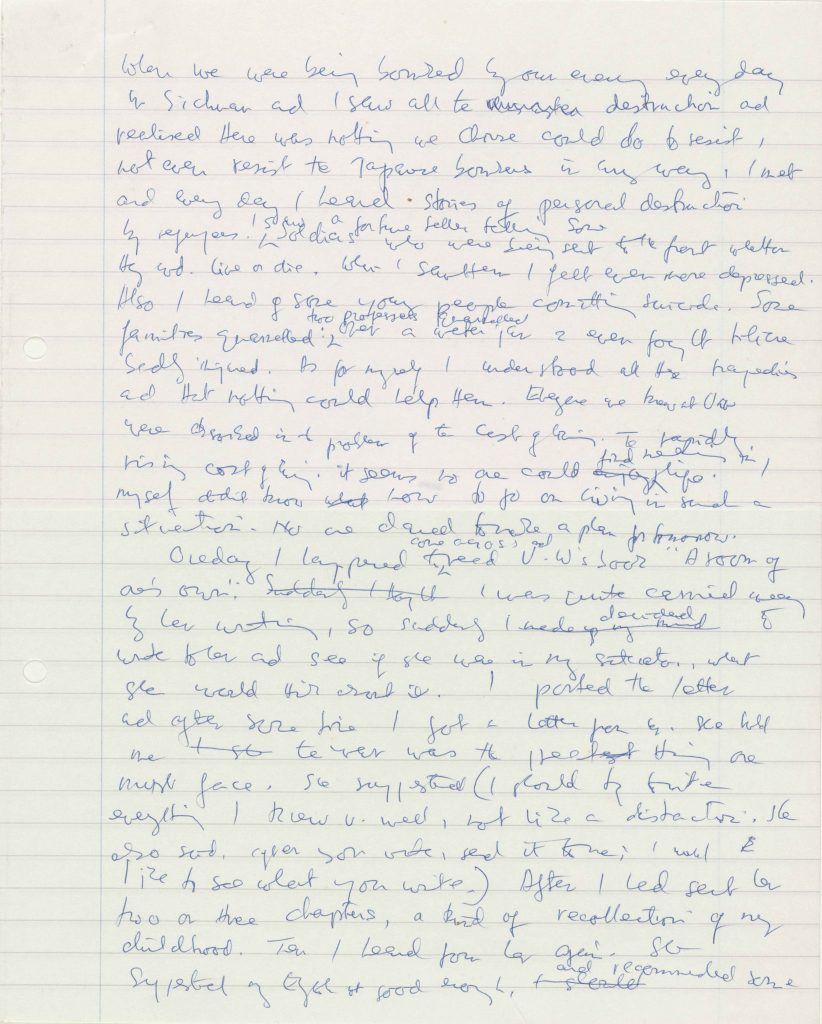

标题:Letter from Virginia Woolf to Ling Shuhua, 15 Oct 1938

作者/创作者:Virginia Woolf

藏品存于:New York Public Library

版权:© The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Virginia Woolf / Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work.

Both women were ‘the daughters of educated men’: Ling, the daughter of the mayor of Peking, and Woolf of Leslie Stephen, a literary figure and well-known author of the The Dictionary of National Biography. Woolf was the more established writer (she was 18 years Shuhua’s senior) and had published all of her major works except Three Guineas and Between the Acts by the time they were in correspondence. Ling was an Anglophile and knew English before she met Julian; her husband Chen Xiying, who attended the London School of Economics, also shared her liking for England. Ling was known mainly as a painter and a writer of short stories and children’s stories, venturing into the field of memoir and autobiography in 1937 with no female tradition in these genres behind her. Woolf illuminated this tradition for her in her letters and books, confirming the value of transnational literary conversation.

标题:Three Guineas

作者/创作者:Virginia Woolf

藏品存于:British Library

书架号:Cup.407.h.32.

版权:© The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Virginia Woolf. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work.

标题:Three Guineas

作者/创作者:Virginia Woolf

藏品存于:British Library

书架号:Cup.407.h.32.

版权:© The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Virginia Woolf. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work.

标题:Three Guineas

作者/创作者:Virginia Woolf

藏品存于:British Library

书架号:Cup.407.h.32.

版权:© The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Virginia Woolf. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work.

标题:Three Guineas

作者/创作者:Virginia Woolf

藏品存于:British Library

书架号:Cup.407.h.32.

版权:© The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Virginia Woolf. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work.

<前页

后页>

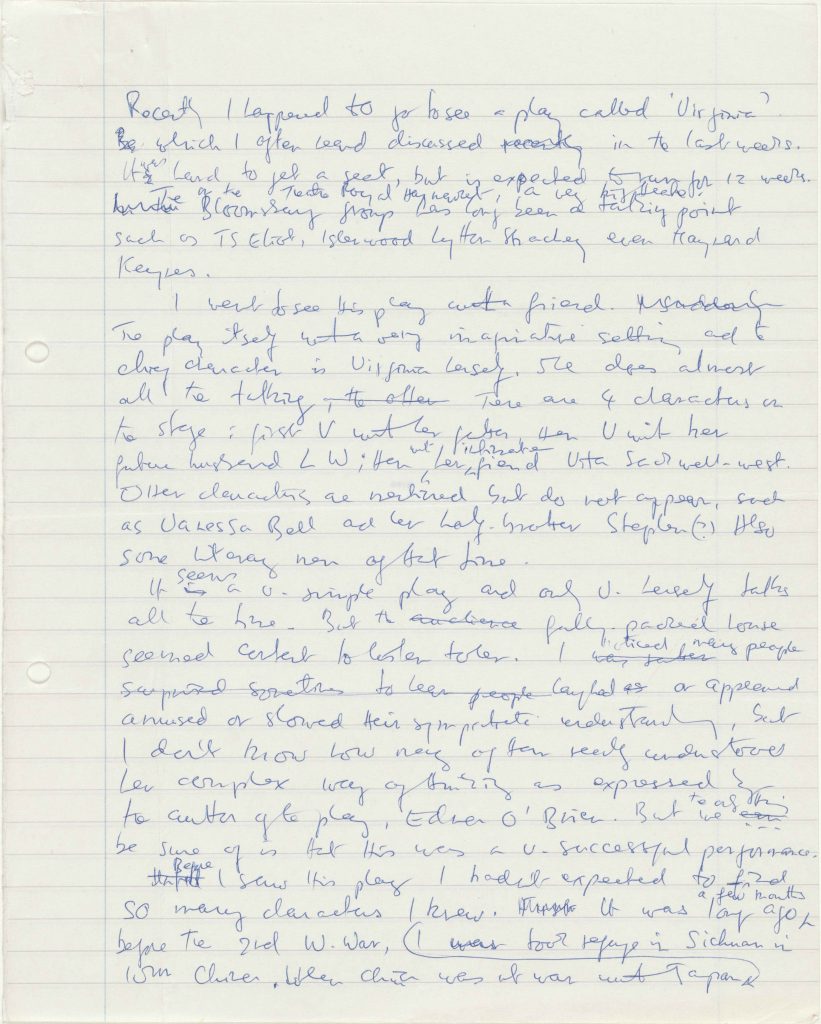

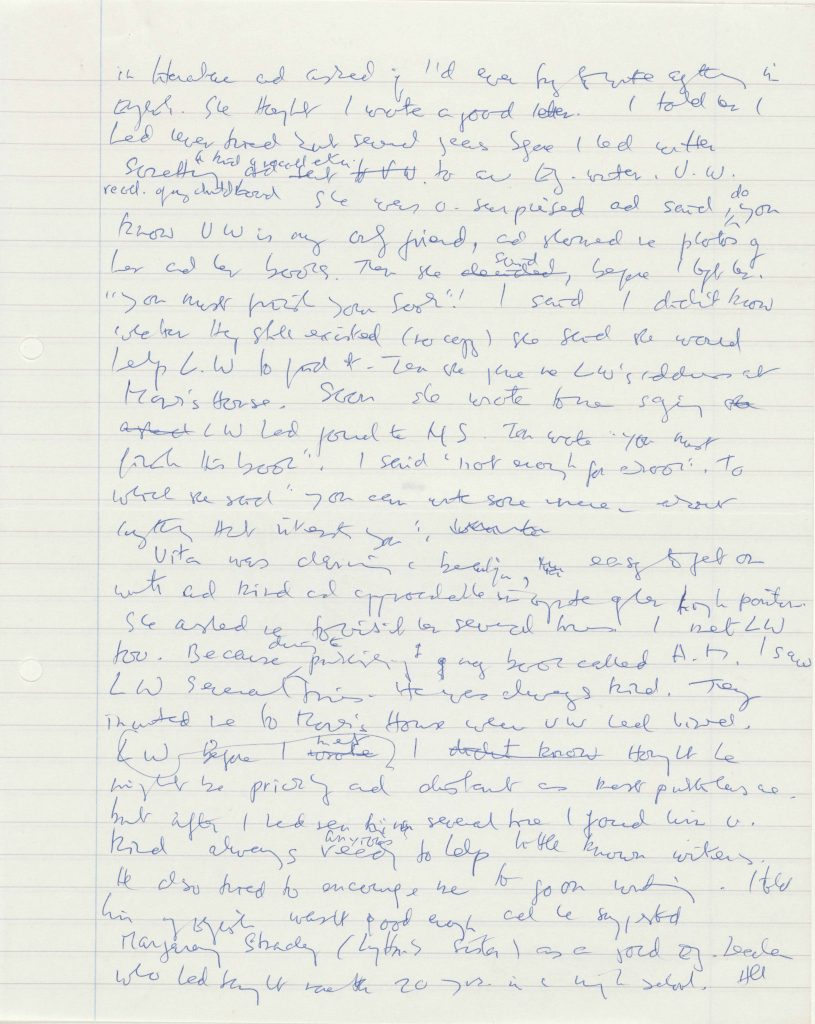

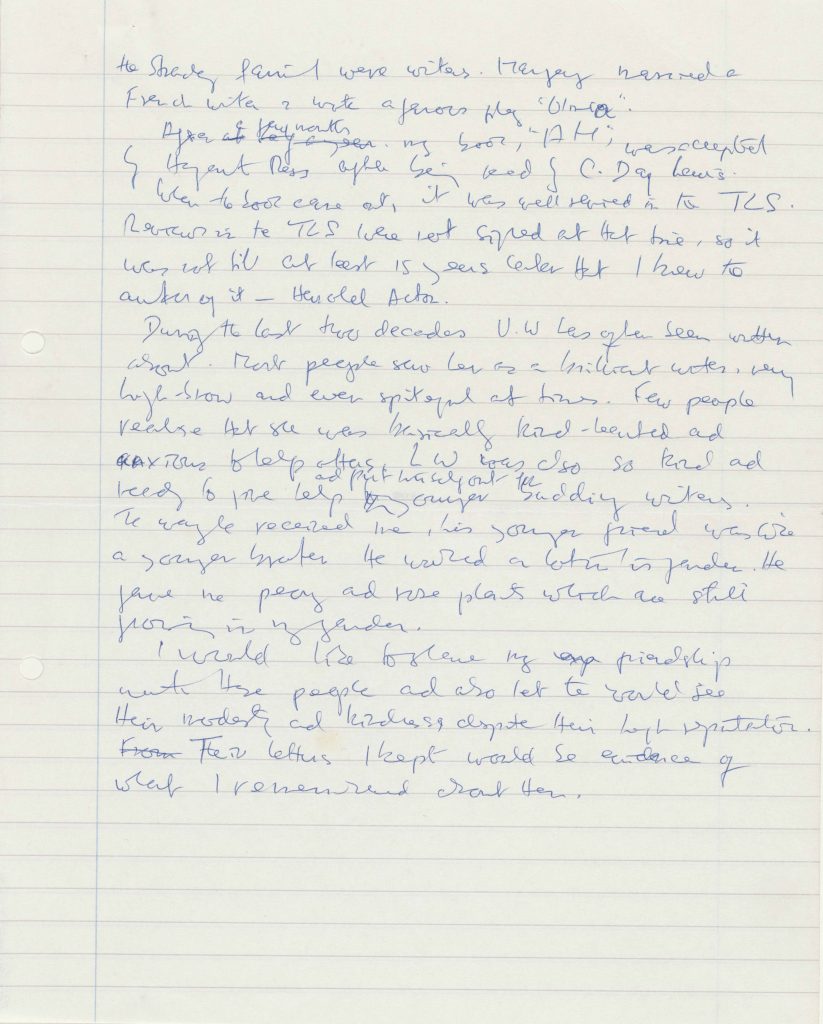

Earlier, in 1935, Julian Bell had suggested to Ling that she publish her work in England, and he collaborated with her in translating her short stories. He sent the translations to his mother Vanessa Bell, but despite her intervention they were rejected by the London Mercury. After Julian’s death, Woolf sent Ling copies of A Room of One’s Own, The Years and The Waves. Ling’s response to these works is recorded in a fragmented memoir that she wrote in the late 1940s in London (it begins with her comments about Edna O’Brien’s play about Woolf, a play that expanded Ling’s sense of the Bloomsbury group). In her memoir, she wrote:

One day I happened to come across and read Virginia Woolf’s book, A Room of One’s Own, and I was quite carried away by her writing, so suddenly I decided to write and see if she were in my situation what she would do.

标题:Undated manuscript of Memoir of Virginia Woolf

作者/创作者:Ling Shuhua

藏品存于:New York Public Library

版权:© Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations / With kind permission from the Estate of Shuhua Ling

标题:Undated manuscript of Memoir of Virginia Woolf

作者/创作者:Ling Shuhua

藏品存于:New York Public Library

版权:© Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations / With kind permission from the Estate of Shuhua Ling

标题:Undated manuscript of Memoir of Virginia Woolf

作者/创作者:Ling Shuhua

藏品存于:New York Public Library

版权:© Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations / With kind permission from the Estate of Shuhua Ling

标题:Undated manuscript of Memoir of Virginia Woolf

作者/创作者:Ling Shuhua

藏品存于:New York Public Library

版权:© Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations / With kind permission from the Estate of Shuhua Ling

标题:Undated manuscript of Memoir of Virginia Woolf

作者/创作者:Ling Shuhua

藏品存于:New York Public Library

版权:© Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations / With kind permission from the Estate of Shuhua Ling

<前页

后页>

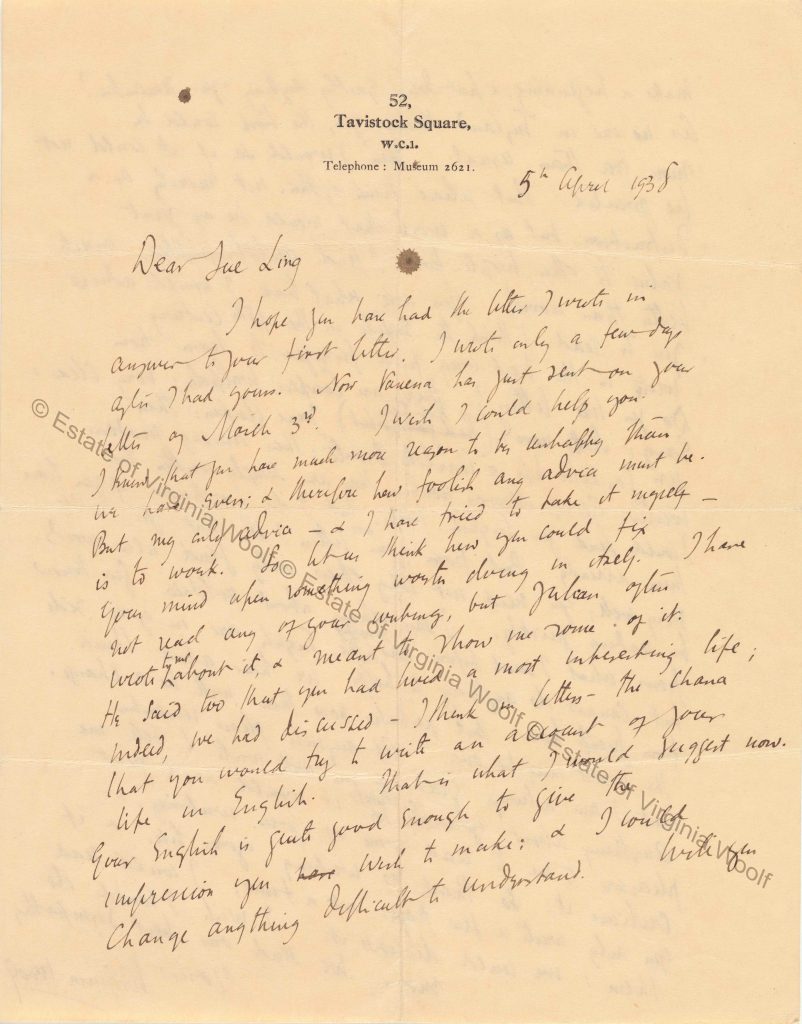

Carried away by Woolf’s polemic, and emboldened by her call for women to write, Ling wrote and asked Woolf what she would do in her wartime situation. Woolf replied that Ling should write of what she knew and send her writing on to her.

标题:Letter from Virginia Woolf to Ling Shuhua, 5 Apr 1938

作者/创作者:Virginia Woolf

藏品存于:New York Public Library

版权:© The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Virginia Woolf / Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work.

标题:Letter from Virginia Woolf to Ling Shuhua, 5 Apr 1938

作者/创作者:Virginia Woolf

藏品存于:New York Public Library

版权:© The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Virginia Woolf / Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work.

标题:Letter from Virginia Woolf to Ling Shuhua, 16 July 1939

作者/创作者:Virginia Woolf

藏品存于:New York Public Library

版权:© The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Virginia Woolf / Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work.

标题:Letter from Virginia Woolf to Ling Shuhua, 27 July 1938

作者/创作者:Virginia Woolf

藏品存于:New York Public Library

版权:© The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Virginia Woolf / Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work.

标题:Letter from Virginia Woolf to Ling Shuhua, 27 July 1938

作者/创作者:Virginia Woolf

藏品存于:New York Public Library

版权:© The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Virginia Woolf / Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work.

<前页

后页>

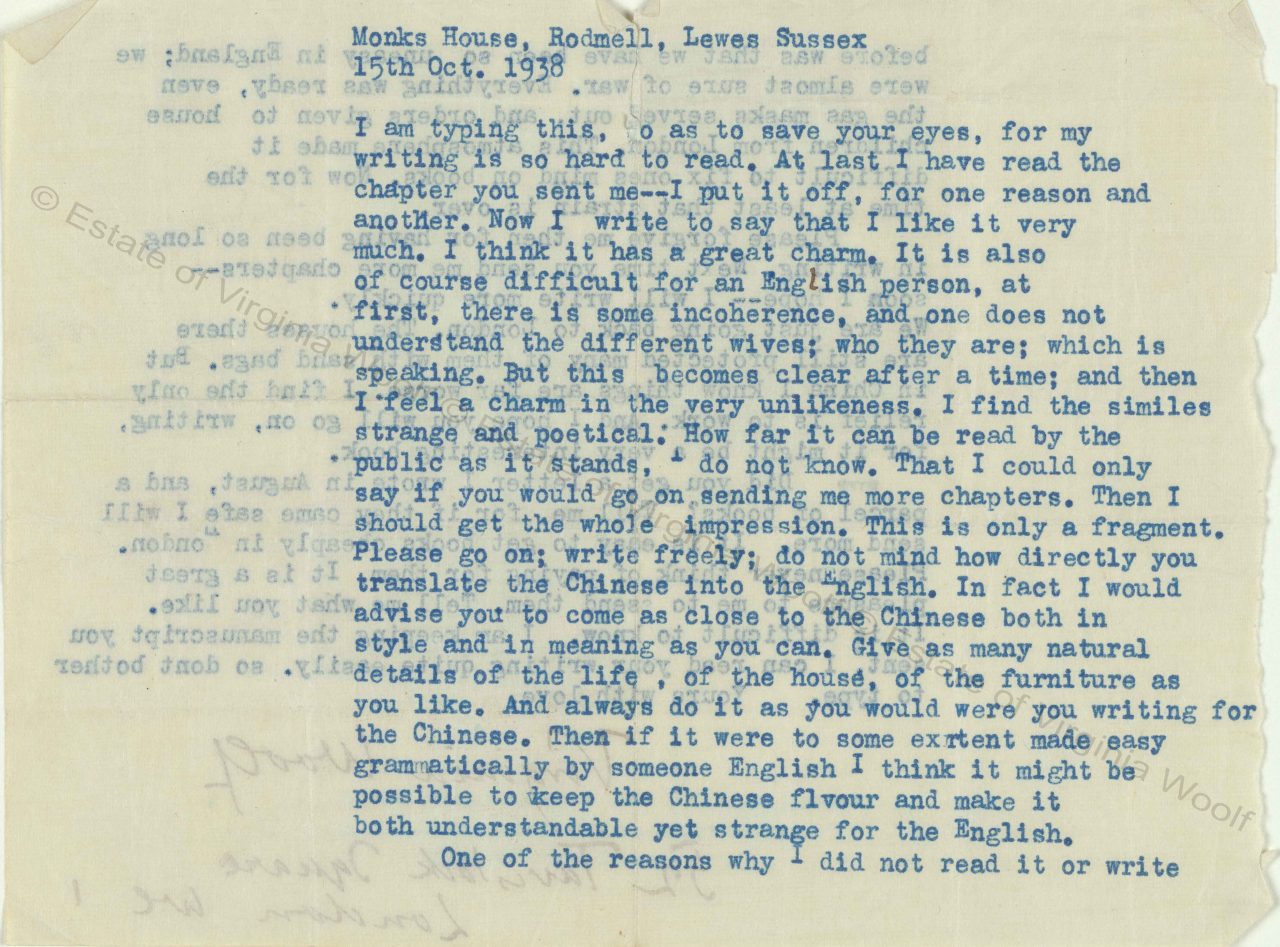

Ling eventually wrote her autobiography in English, her second language, addressing Woolf as ‘laoshi’ (teacher). Woolf, surprisingly, gave writerly advice that counters what most editors or creative writing teachers today would give a foreign writer who writes in English as a second language. In an early 1938 letter, Woolf responded to the chapters she sent, ‘I write to say that I like it very much. I think it has a great charm … I feel a charm in the very unlikeness. I find the similes strange and poetical’. Woolf valued the ‘strangeness’ in Ling’s style and urged her to ‘come as close to the Chinese both in style and in meaning as you can’. She continued, ‘Give as many natural details of the life, of the house, of the furniture as you like. And always do it as you would were you writing for the Chinese’. In that way she would preserve ‘the Chinese flavour’ and yet make it understandable and strange for the English.

标题:Letter from Virginia Woolf to Ling Shuhua, 15 Oct 1938

作者/创作者:Virginia Woolf

藏品存于:New York Public Library

版权:© The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Virginia Woolf / Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work.

标题:Letter from Virginia Woolf to Ling Shuhua, 15 Oct 1938

作者/创作者:Virginia Woolf

藏品存于:New York Public Library

版权:© The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Virginia Woolf / Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work.

标题:Letter from Ling Shuhua to Virginia Woolf, 12 Dec 1938

作者/创作者:Ling Shuhua

藏品存于:New York Public Library

版权:© Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations / With kind permission from the Estate of Shuhua Ling

标题:Letter from Ling Shuhua to Virginia Woolf, 16 Nov 1938

作者/创作者:Ling Shuhua

藏品存于:New York Public Library

版权:© Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations / With kind permission from the Estate of Shuhua Ling

<前页

后页>

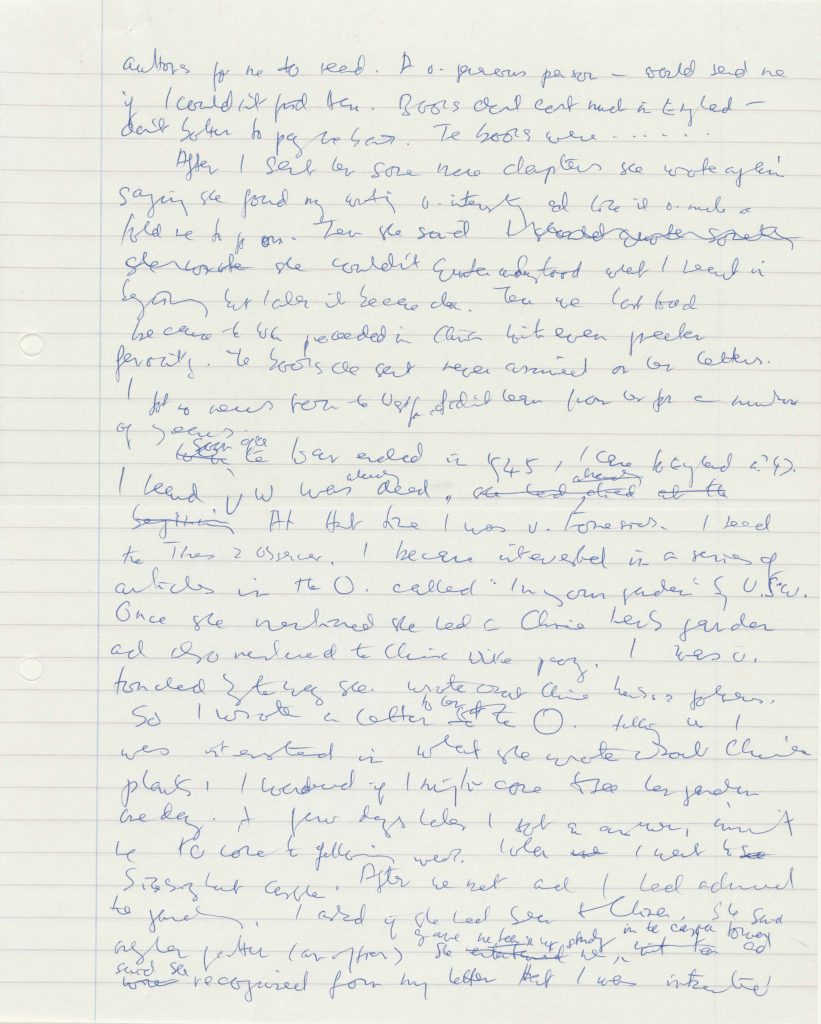

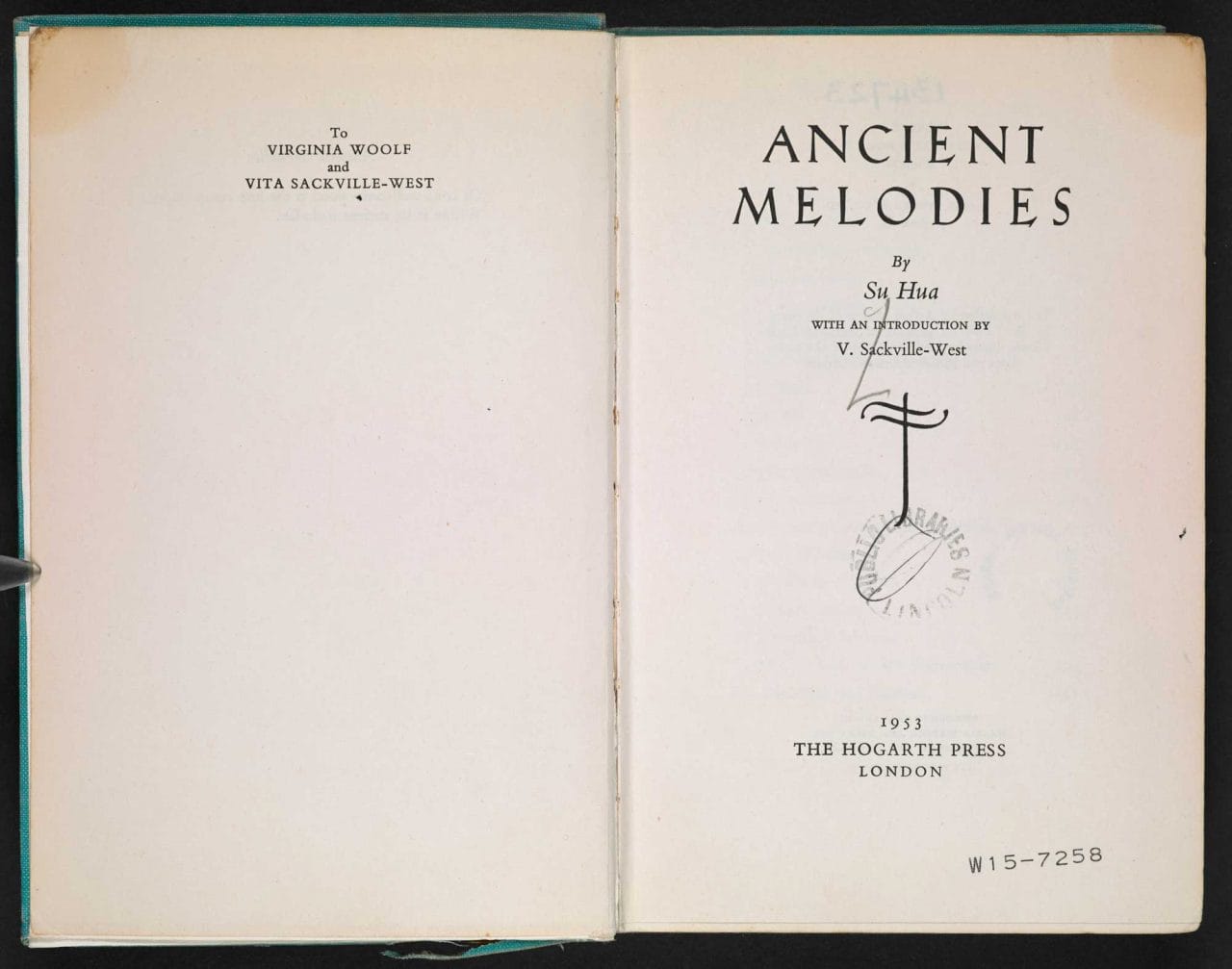

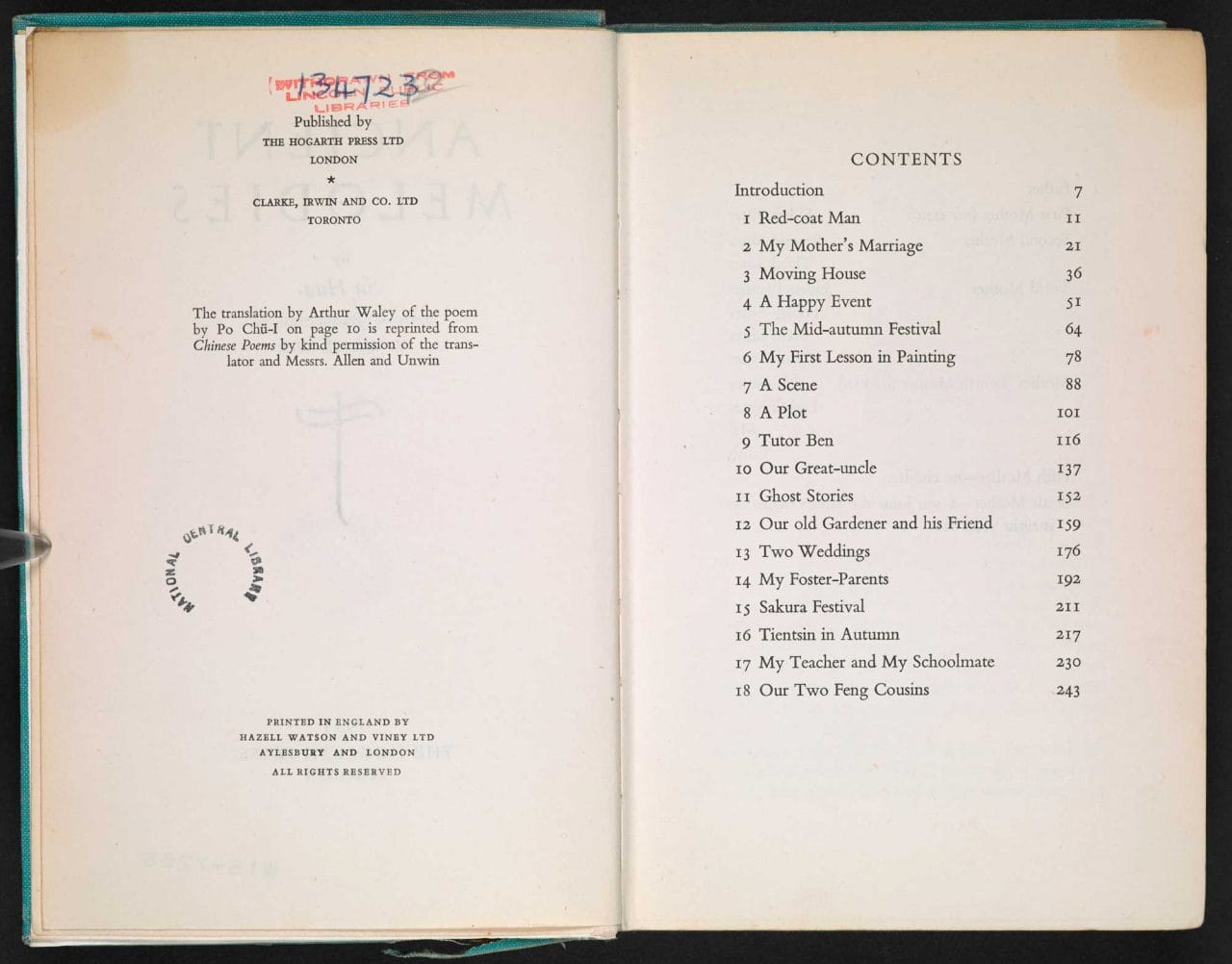

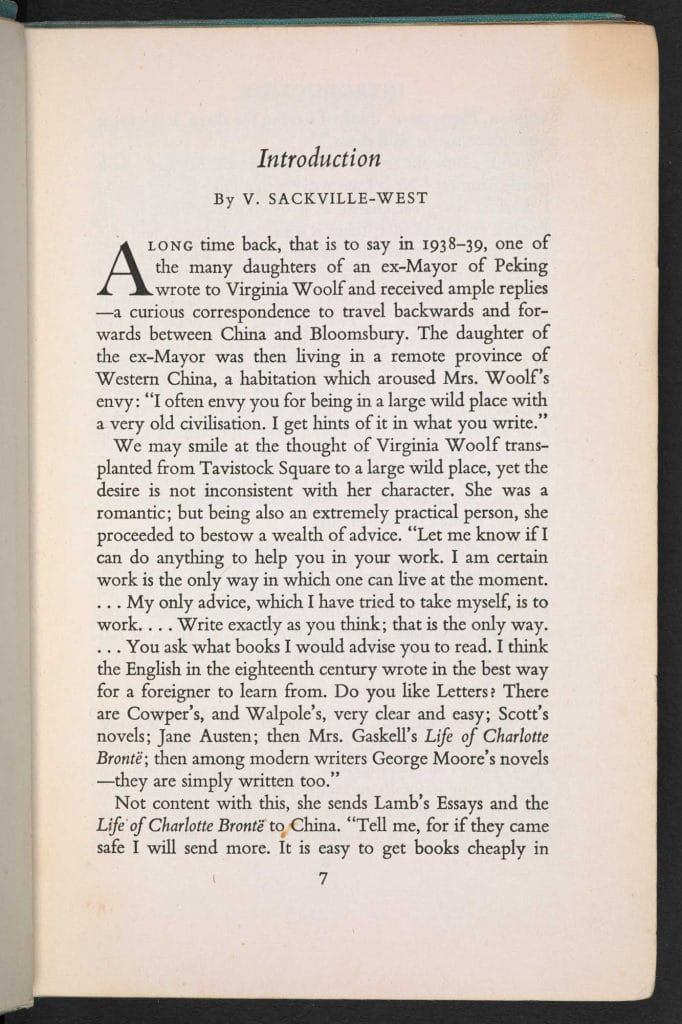

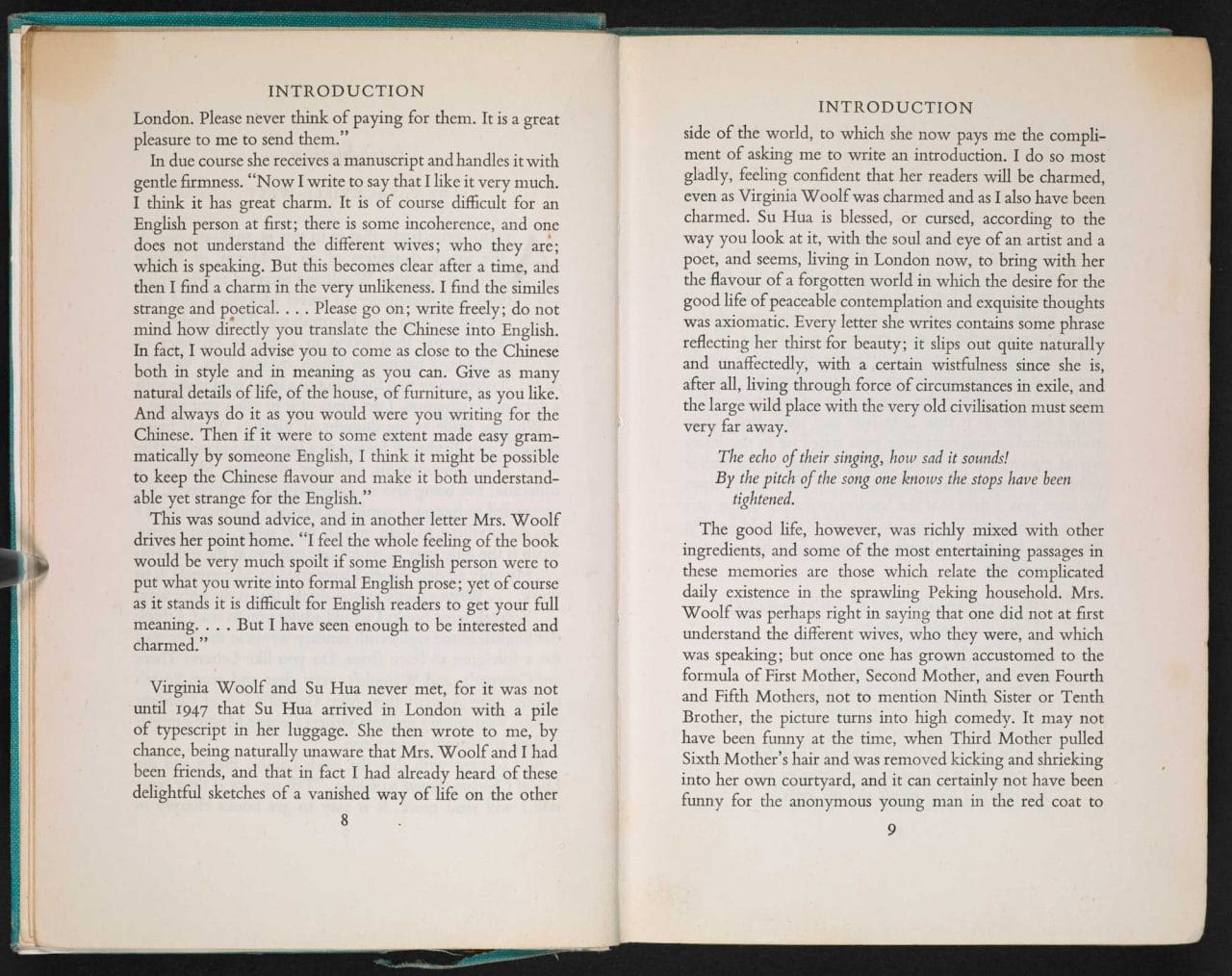

Though Ling urged ‘tell me the mistakes I have made’, worrying about syntax and grammar, Woolf said little as respecting the foreign accent of the writing, the angle of vision and the unexpected emphases in her style. Ling did finish her autobiography, Ancient Melodies, and added drawings of domestic scenes in China. It was edited by Woolf’s friend Vita Sackville-West, after Woolf’s death, and published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press in 1953.

标题:Title page of Ancient Melodies

作者/创作者:Shuhua Ling

藏品存于:British Library

书架号:W15/7258

版权:With kind permission from the Estate of Shuhua Ling

标题:Ancient Melodies

作者/创作者:Shuhua Ling

藏品存于:British Library

书架号:W15/7258

版权:With kind permission from the Estate of Shuhua Ling

标题: Ancient Melodies, first edition, with an Introduction by V Sackville-West

作者/创作者:Shuhua Ling

藏品存于:British Library

书架号:W15/7258

版权:With kind permission from the Estate of Shuhua Ling

标题: Ancient Melodies, first edition, with an Introduction by V Sackville-West

作者/创作者:Shuhua Ling

藏品存于:British Library

书架号:W15/7258

版权:With kind permission from the Estate of Shuhua Ling

标题: Ancient Melodies, first edition, with an Introduction by V Sackville-West

作者/创作者:Shuhua Ling

藏品存于:British Library

书架号:W15/7258

版权:With kind permission from the Estate of Shuhua Ling

<前页

后页>

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Patricia Laurence

Patricia Laurence is a writer, critic and Emeritus Professor of English of the City College of New York, CUNY. She is a specialist in transnational modernism, modernist women’s writing, Virginia Woolf and Bloomsbury studies, and Republican era literature of China. Her published works include The Reading of Silence: Virginia Woolf in the English Tradition (1994); Lily Briscoe’s Chinese Eyes: Bloomsbury Modernism and China (2003), and a short biography, Julian Bell, the Violent Pacifist (2005). Her biography of Elizabeth Bowen is forthcoming from Northwestern UP.