An introduction to The Importance of Being Earnest

The Importance of Being Earnest draws on elements of farce and melodrama in its depiction of a particular social world. Professor John Stokes considers how Oscar Wilde combined disparate influences into a brilliant satire which contained hidden, progressive sentiments.

A complaint voiced later by a fellow playwright, George Bernard Shaw, that The Importance of being Earnest was Wilde’s ‘first really heartless play,’ [1] ultimately makes a point in its author’s favour. Although far from caricatures, Wilde’s characters are scrupulously self-interested and they bear a deliberately simplified and parodic relationship to the aristocracy of his own time. They speak a language that sounds similar to how we might imagine members of that class to have spoken yet doesn’t pretend to be an exact reproduction. In fact, it’s perfectly possible to hear in all the characters echoes of Wilde himself since they are nearly all wits, although their jokes are sometime conscious, sometimes not.

Theatrical and social worlds

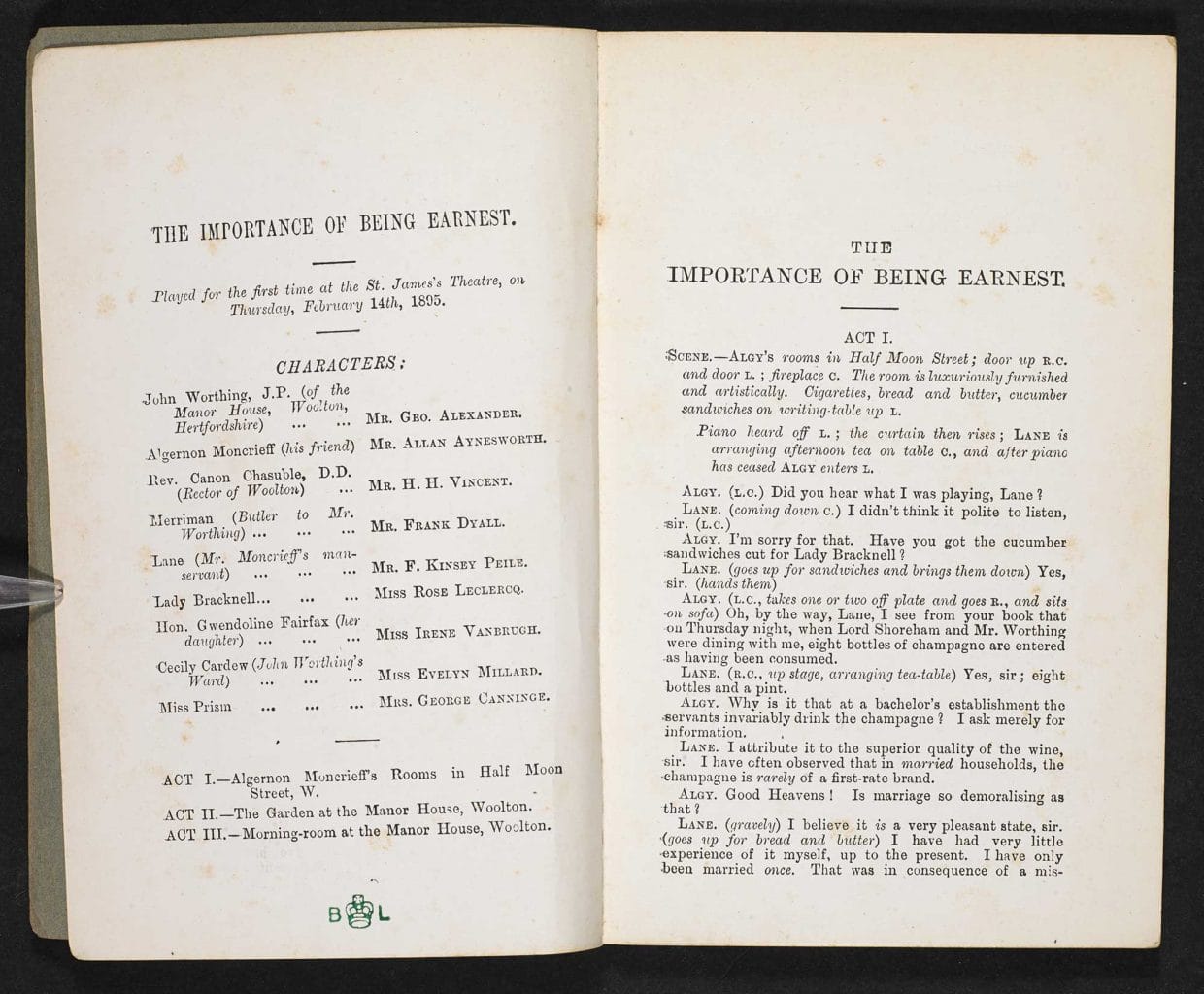

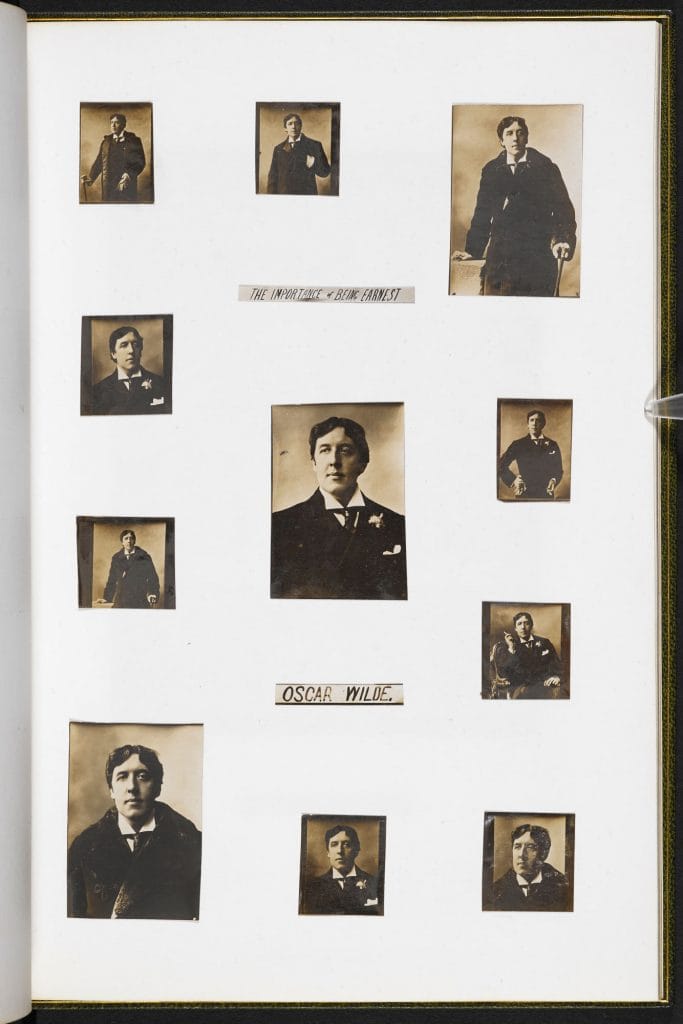

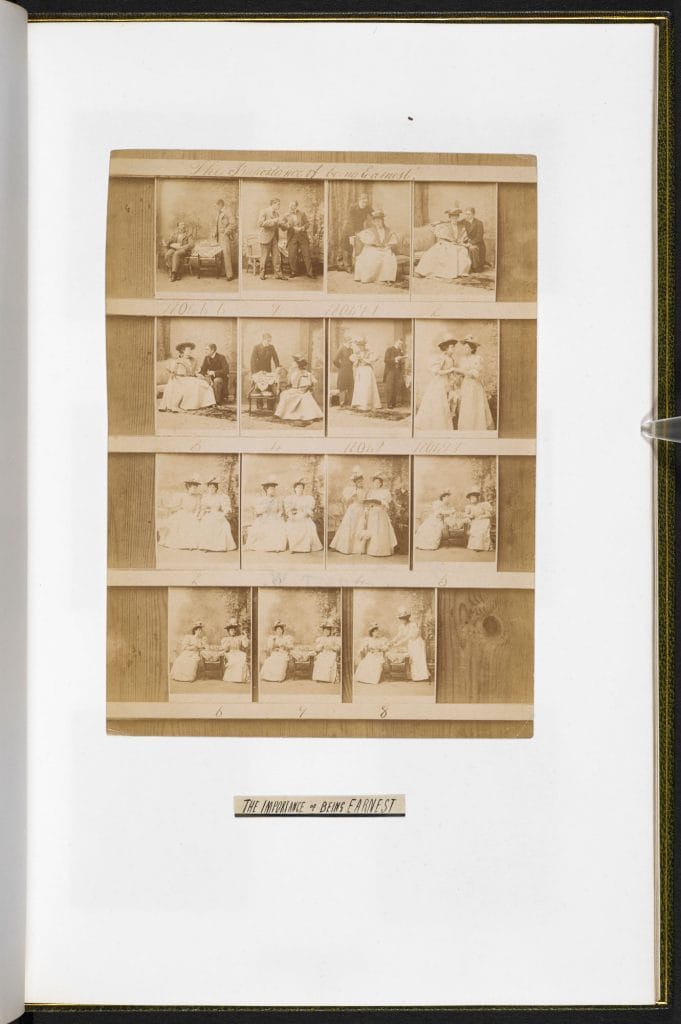

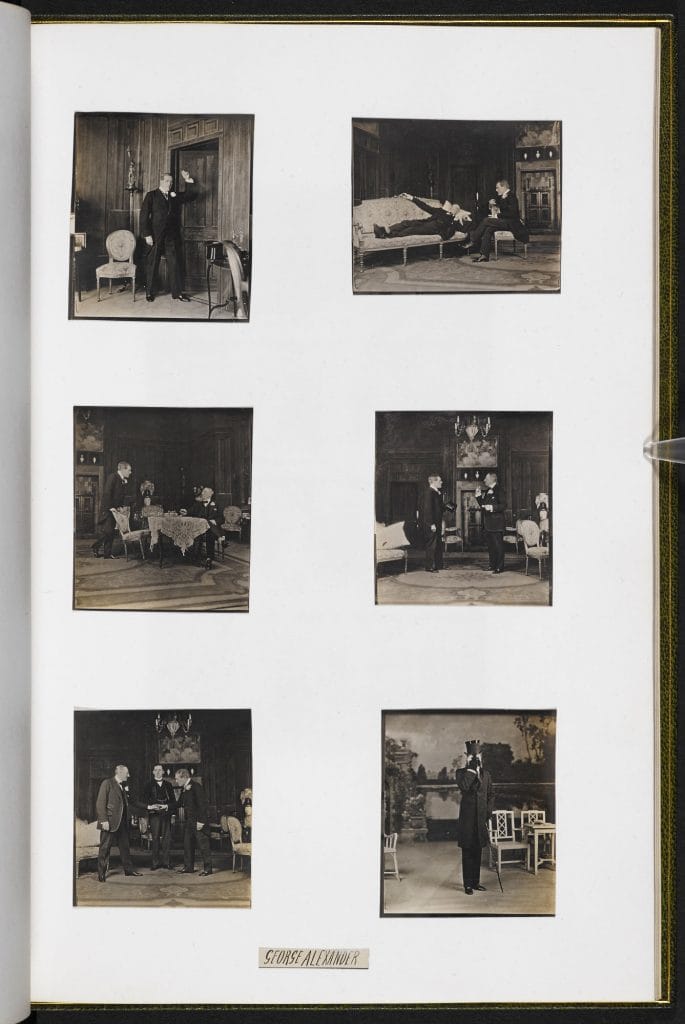

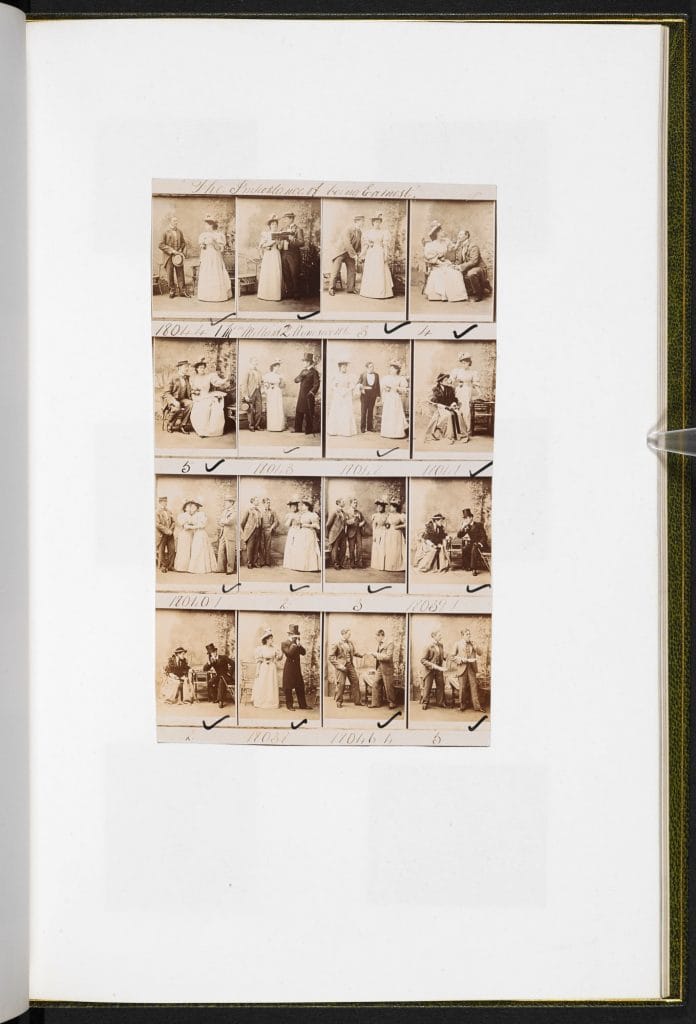

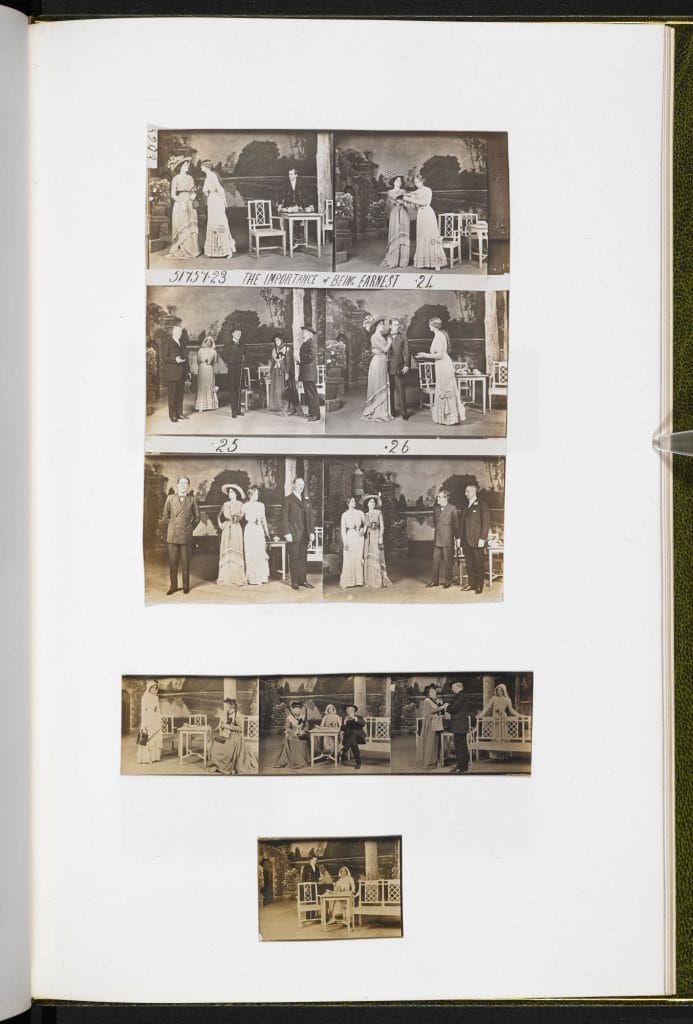

The play opened at the St James’s Theatre in King Street in February 1895, a compact but extremely elegant house then leased by the actor-manager George Alexander. 10 years earlier Wilde had already marked out Alexander as a romantic actor with ‘a most effective presence, a charming voice, and a capacity for wearing lovely costumes with ease and elegance.’[2] In 1892 they had worked together on Lady Windermere’s Fan. Although the actor had strong opinions of his own – and insisted that a surplus act be dropped from The Importance – the partnership was in many ways the ideal match of two urban sophisticates. The St James was situated in the most fashionable part of town with ‘gentleman’s clubs’ to hand and it was not far from the Albany, a long established block of superior bachelor apartments, or from the popular Willis’s restaurant – both of which are mentioned in various versions of the play. The audience at the St James would therefore have seen on stage a reflection, admittedly a distorted one, of a social ambiance that they either knew intimately or had heard a good deal about. Not that The Importance offers a very flattering picture of that world, since it’s characterised by underlying greed (if only for buttered muffins), self-indulgence (none of the major characters actually works) coupled with financial insecurity (Lady Bracknell changes her tune completely the minute she hears of Cecily’s inherited fortune).

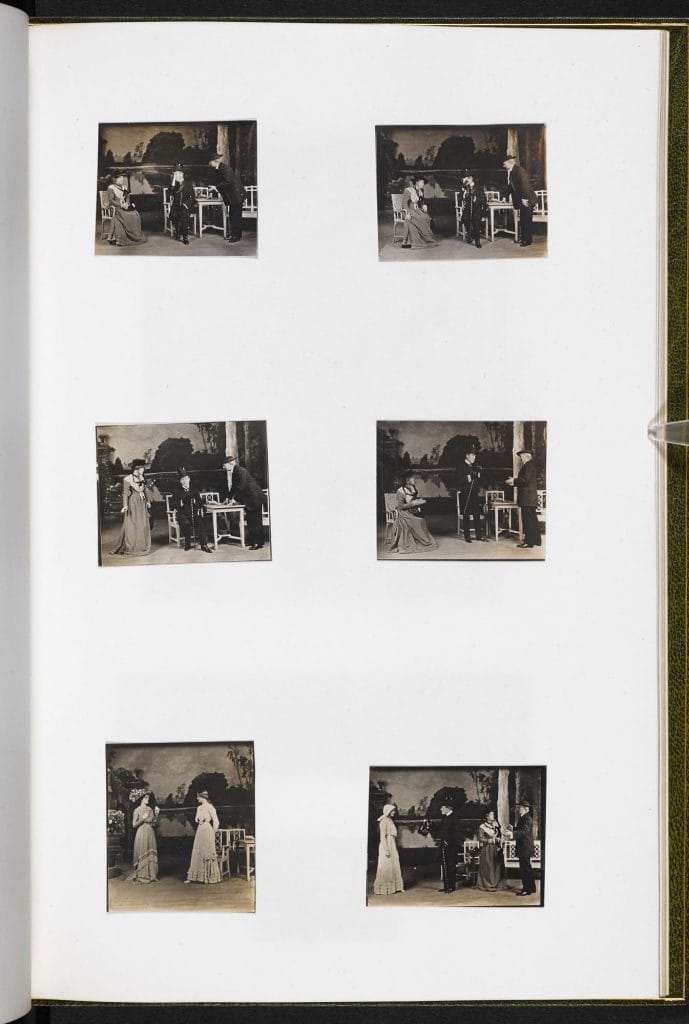

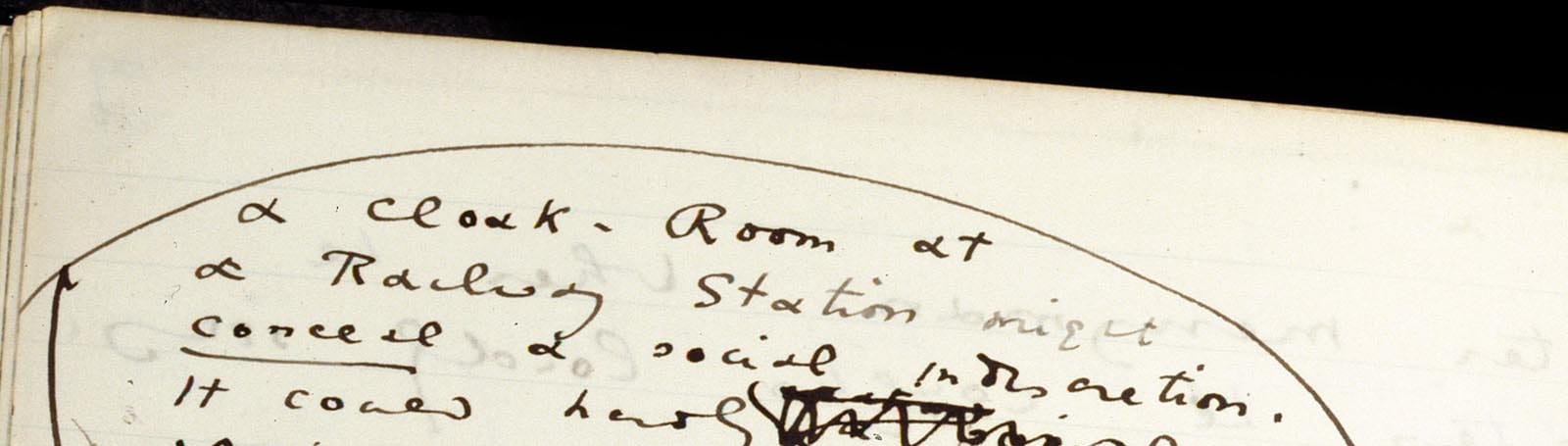

At the same time the action is continuously, uncontrollably and hilariously absurd. This means that it’s not easy to judge the severity of the play’s satiric intent, another aspect of Wilde’s theatrical ingenuity. What is beyond dispute is his brilliance in devising scenes where the comedy is inbuilt and the dialogue resonates with repressed feeling. Examples are Lady Bracknell’s autocratic cross examination of Jack in Act 1, the tea-party scene in Act II where the two women are obliged to make icily polite chit-chat while balancing cups and plates, and the strangely suggestive, though entirely innocent, exchanges between Canon Chasuble and Miss Prism. Objects – ‘theatrical props’ – play their part too. Algernon’s salver bearing cucumber sandwiches, Lady Bracknell’s pen and notebook (in which she keeps a record of contenders in the marriage market), Jack’s inscribed cigarette case, Miss Prism’s battered handbag: all focus our attention on the distinctive accessories of a specific social world.

Place in the repertoire

Although we think, quite rightly, of The Importance as a unique comic achievement, Alexander and his fellow actors were all at home in the Victorian repertoire and well-practised in audience technique. The Importance is original mainly in the perfection of its plot and its consummate style, and it draws on a calculated mix of genres: burlesque, comedy of manners, melodrama and, perhaps most of all, farce. As a reviewer conceded in 1895: ‘the very fact that Mr. Wilde’s inspiration can be traced to so many sources proves that he can owe very little to any of them and I, for one, certainly do not intend to upbraid him for his eclectic taste’.[3] Farce loves symmetry and The Importance draws on an established tradition in which pairs of characters swap roles and mirror one another. Obvious precedents include Box and Cox by J M Morton (1847) and W S Gilbert’s Engaged (1877). The theatre historian Kerry Powell has even shown that Wilde’s sublime masterpiece has a surprising amount in common with a long forgotten farce entitled The Foundling that had been performed as recently as 1894. [4] Although brilliantly structured The Importance isn’t, in the end, entirely symmetrical because Algernon’s name remains unchanged despite Cecily’s earlier fascination with her ‘wicked cousin Ernest’. A loose end or two makes the triumph of desire over circumstance all the more remarkable and welcome.

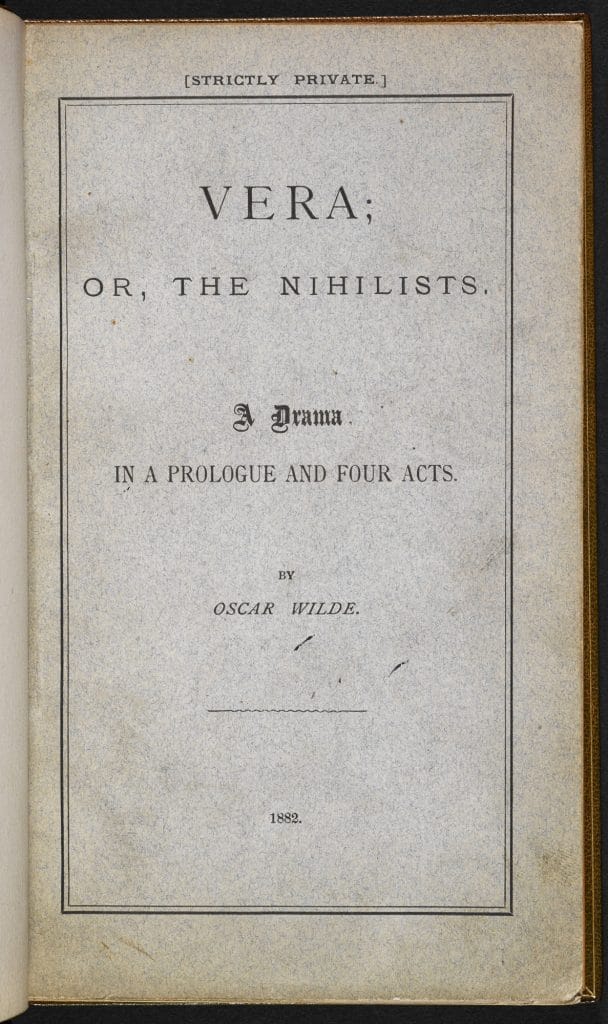

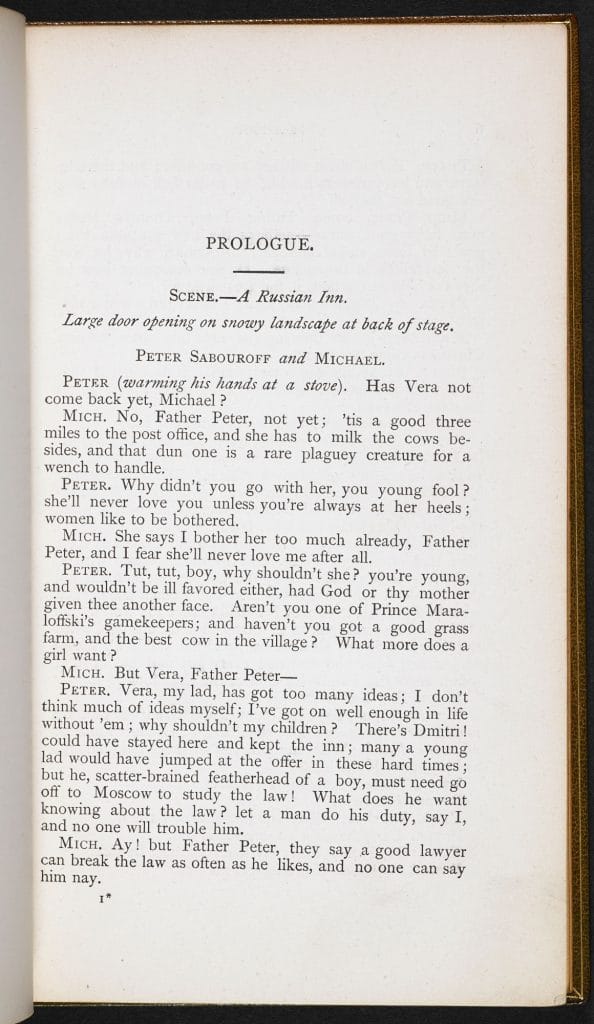

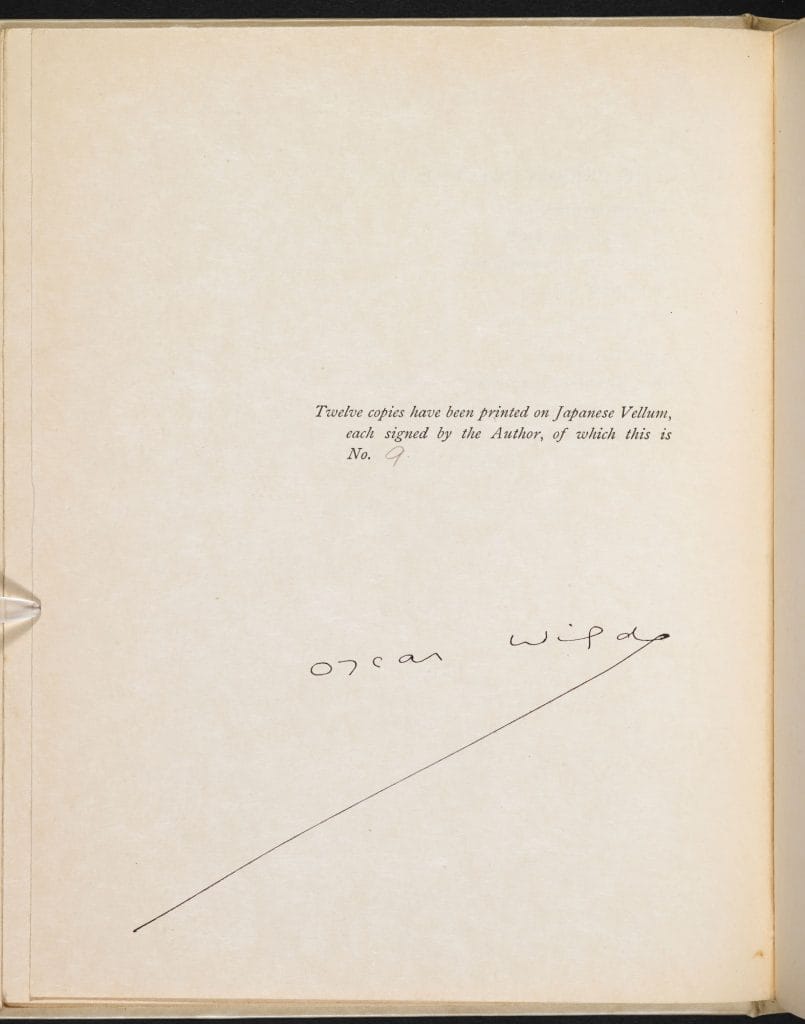

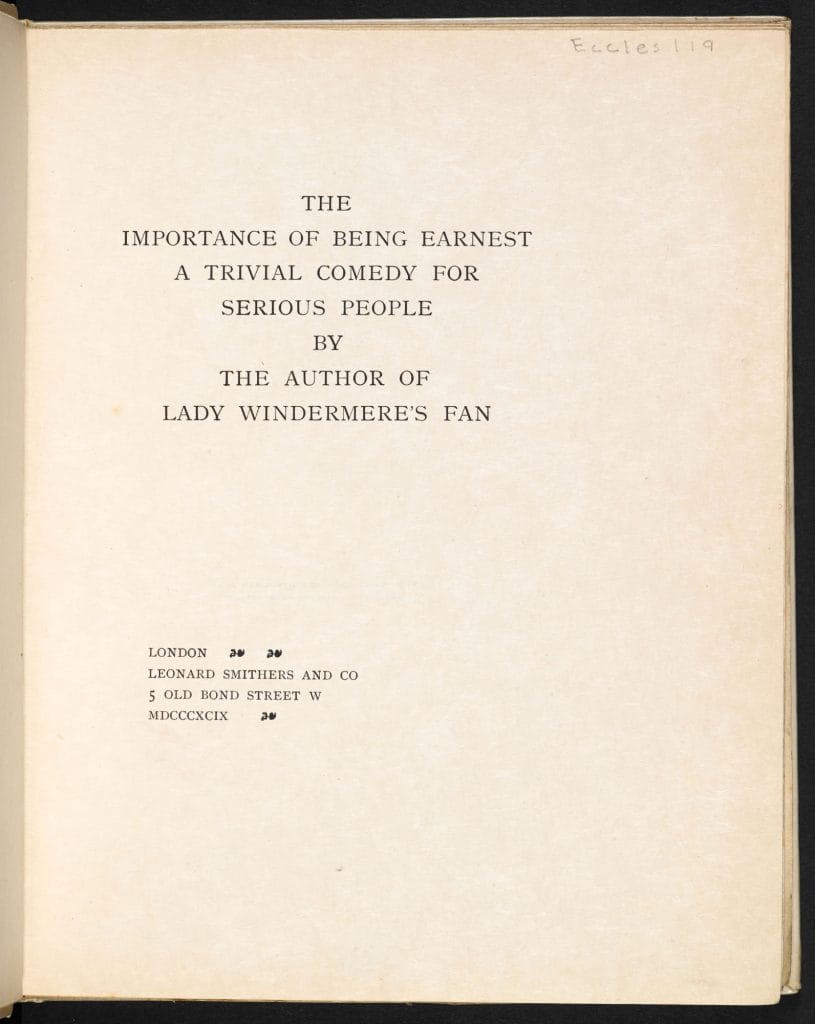

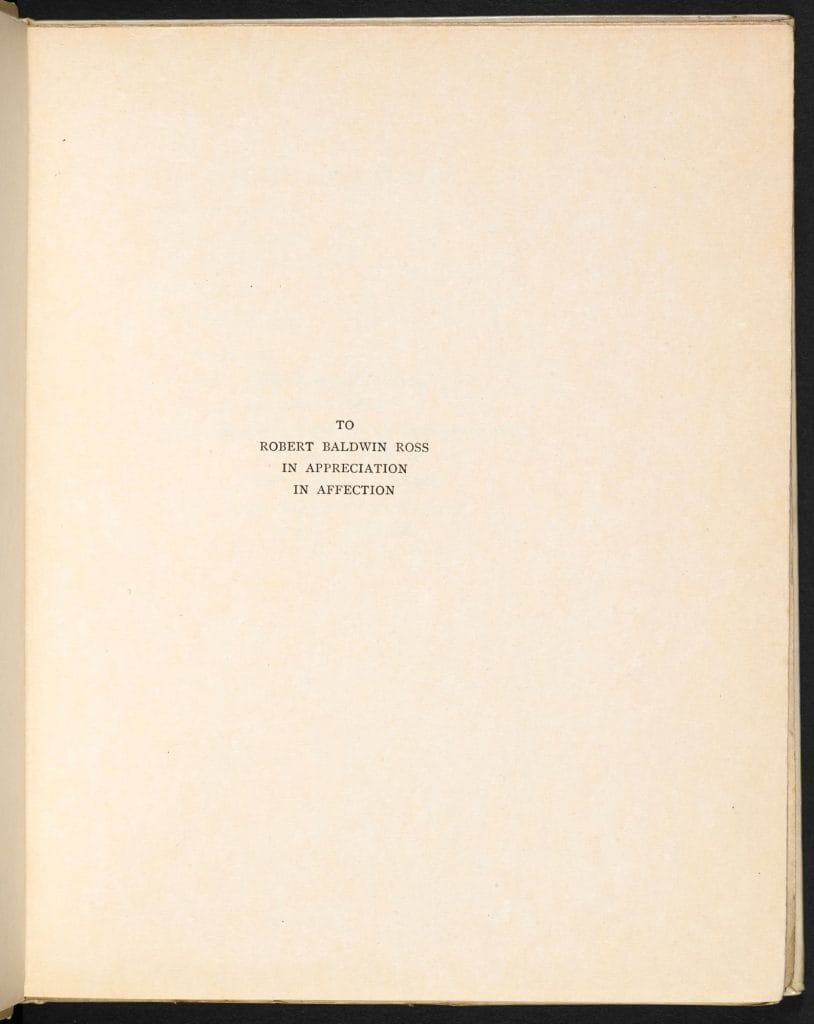

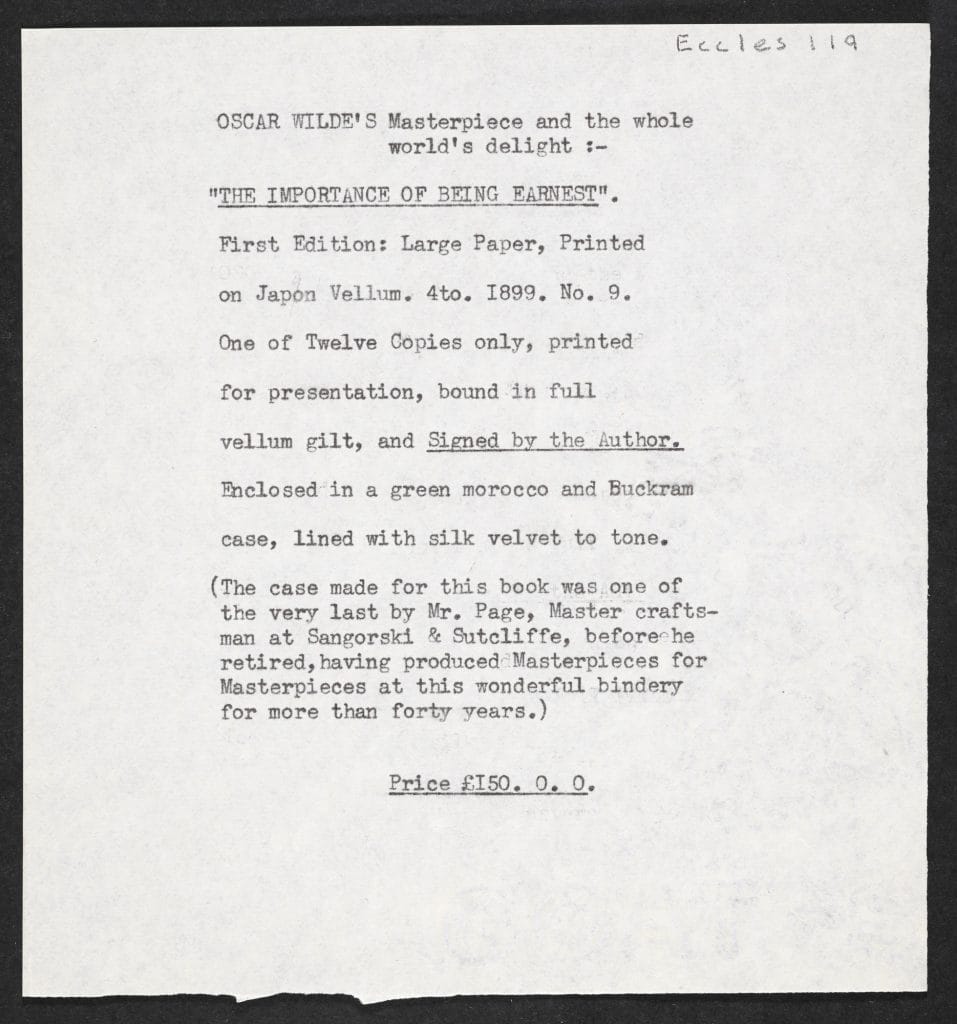

The earliest influences on Wilde as a playwright were essentially melodramatic – as in his Russian Nihilist drama Vera (1883) or the historical period piece The Duchess of Padua (staged in 1891, but written in the early 1880s). These failed to attract either serious attention or substantial audiences, but by the early 1890s Wilde had moved on from the mainly melodramatic to explore a hybrid form of ‘Society Drama’ that combined characteristically epigrammatic dialogue with plots based around carefully nuanced moral issues. Lady Windermere’s Fan was followed by A Woman of No Importance (1893), and (running concurrently with The Importance of Being Earnest) An Ideal Husband (1895). He was not alone in this move. Ambitious English dramatists of the time refused to be confined to dour imitations of Ibsen or of the hysterical French dramas of adultery associated with the likes of Dumas fils, author of La dame aux camélias. Henry Arthur Jones, Arthur Pinero, even Shaw, all experimented with a mixture of homegrown comedy and ethical dilemma. It was a usefully compromised solution to current demands that the theatre become a respectable cultural milieu, its products elevated to the status of ‘literature’. The publication of play texts in book form was seen as a part of this process and it’s significant that even after his calamitous time in Reading Gaol, Wilde was anxious to see his work appear in a handsome edition, which it eventually did in 1899.

Secret meanings and influence

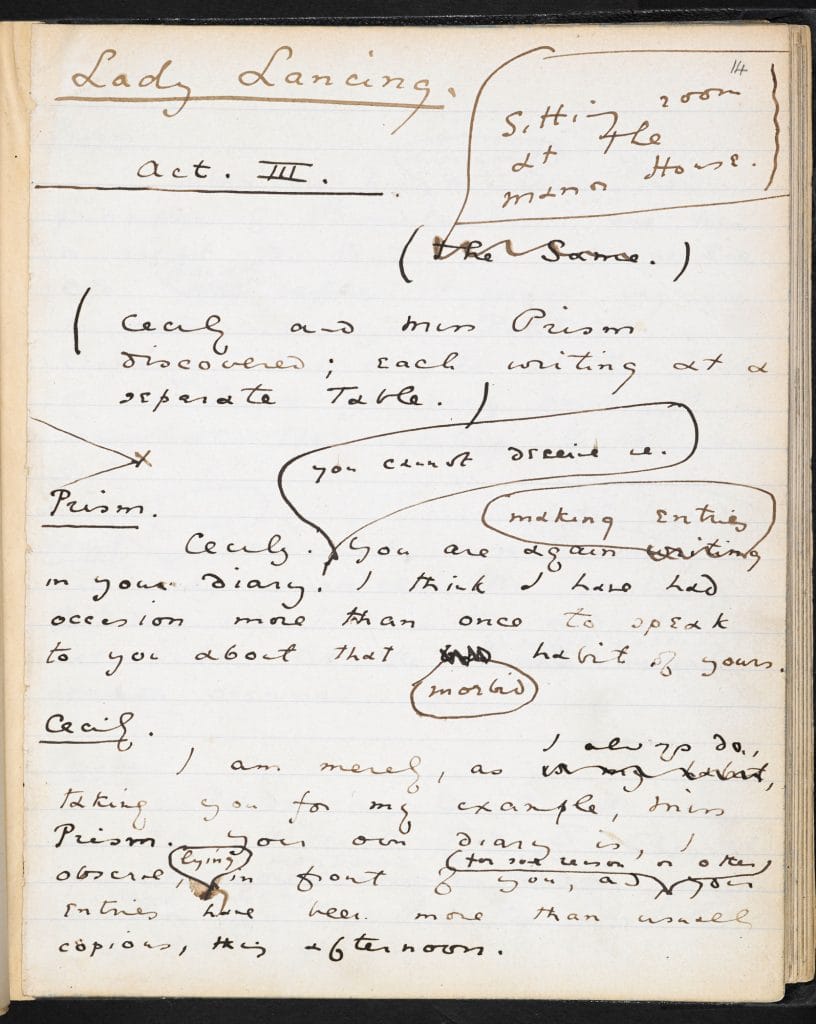

Although sheer good fortune ultimately wins out, Wilde’s ‘Trivial Comedy for Serious People’ is founded upon a mode of intellectual paradox that reveals truth by inverting commonplace wisdom. Even the play’s punning title neatly captures and explodes the dominant Victorian moral principle that sincerity is its own reward. Moreover, the title may even have passed a secret signal to members of Wilde’s circle since the word ‘Earnest’ bears a euphonious relation to the term ‘Uranian’ which was coming to be used to denote homosexual relationships between men of different ages. The idea of a secret life (the ‘Bunbury’ alibi) would certainly seem to reflect the kind of subterfuge that a gay man might be obliged to adopt in the homophobic climate that, following the introduction of the notorious Criminal Law Amendment act of a 1885, threatened offenders with imprisonment. Wilde of course, was to fall foul of that law himself in the spring of 1895. However, the presence of various other sub-textual hints at homosexuality, recently claimed by some academic critics, remains extremely controversial. Although his greatest moment of triumph immediately preceded his social downfall, we should be careful before forcing Wilde’s life into a classically tragic pattern. Not only could he have had no precise idea of what the future might bring when he started to compose the play that he originally called Lady Lancing, it has led an independent life quite apart from the dire misfortune of its author, endlessly revived and inspiring modern plays from Tom Stoppard’s Travesties (1974) to Mark Ravenhill’s Handbag (1998).

As history has shown, The Importance of Being Earnest is both of its time and ahead of its time. Respecting the more progressive views of the period, all Wilde’s plays invariably centre on women who are called upon to realise and demonstrate the superior qualities they possess in comparison with the majority of men. In The Importance Cicely and Gwendolen are as unafraid of expressing themselves as any of the ’New Women’ who were coming into prominence in the real world in the 1890s, and – miraculously – their ambitions are fulfilled in the most surprising and entertaining way imaginable.

脚注

- Quoted by Oscar Wilde (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), p. 128.

- The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, vol. VI: Journalism Part I, ed. by John Stokes and Mark W. Turner (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 48.

- Unsigned review, Truth, 21 February 1895, xxvii, pp. 464-5, repr. Oscar Wilde. The Critical Heritage, ed. by Karl Beckson (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1970), pp. 191-3, p. 192.

- Kerry Powell, ‘The Importance of being at Terry’s’, in Oscar Wilde and the theatre of the 1890s (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), pp. 108-23.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: John Stokes

John Stokes is Emeritus Professor of Modern British Literature at Kings College London. He is interested in the drama of most periods but has specialised in the theatre of the late 19th century. In 2013 Oxford University Press published two volumes of Oscar Wilde’s Journalism that he edited in collaboration with Professor Mark W Turner.