Daughters of decadence: the New Woman in the Victorian fin de siècle

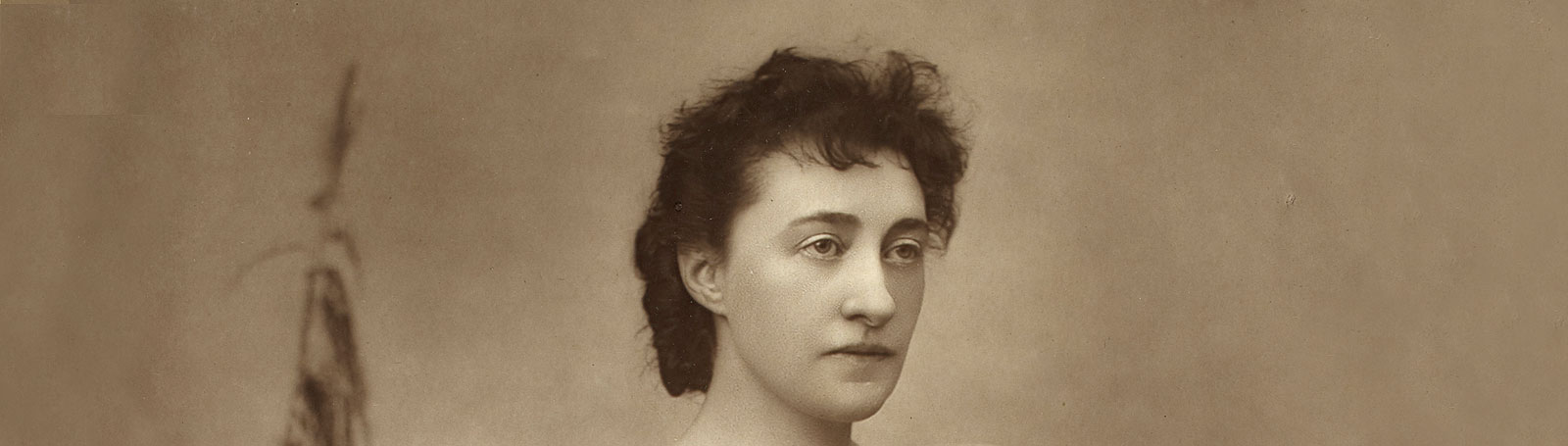

Free-spirited and independent, educated and uninterested in marriage and children, the figure of the New Woman threatened conventional ideas about ideal Victorian womanhood. Greg Buzwell explores the place of the New Woman – by turns comical, dangerous and inspirational – in journalism and in fiction by writers such as Thomas Hardy, George Gissing and Sarah Grand.

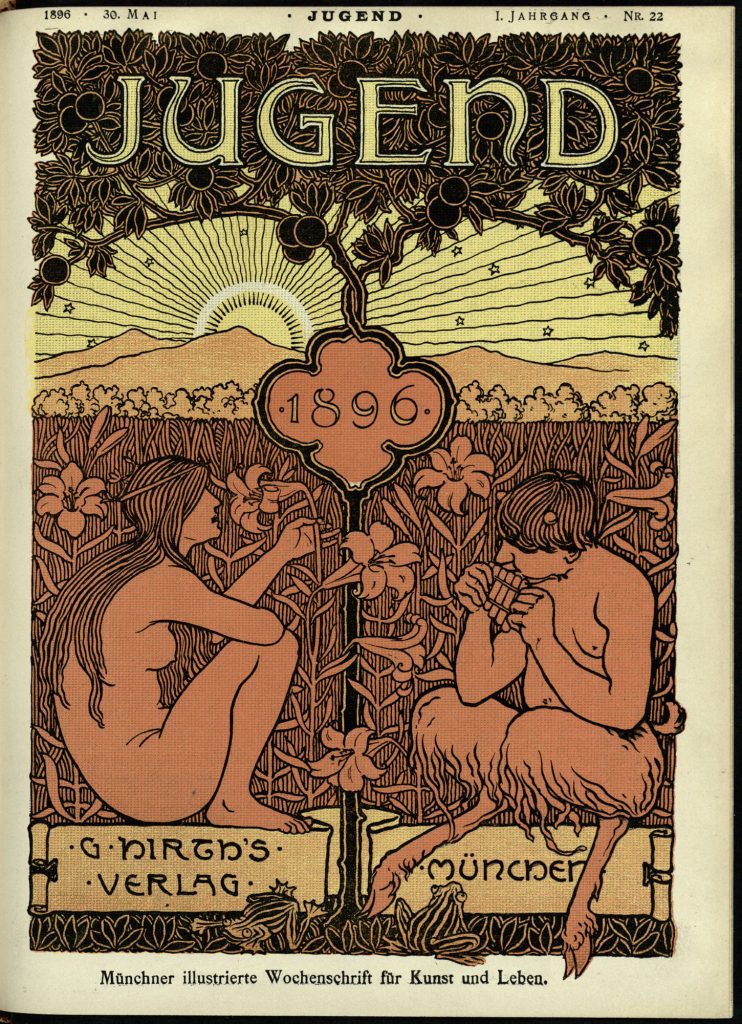

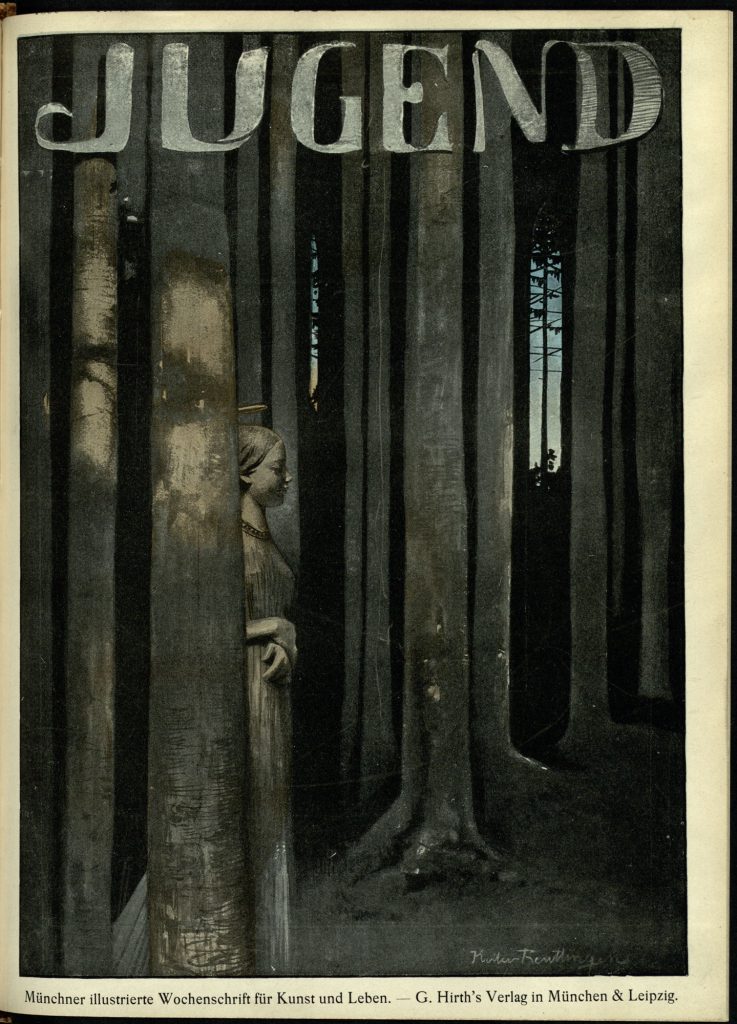

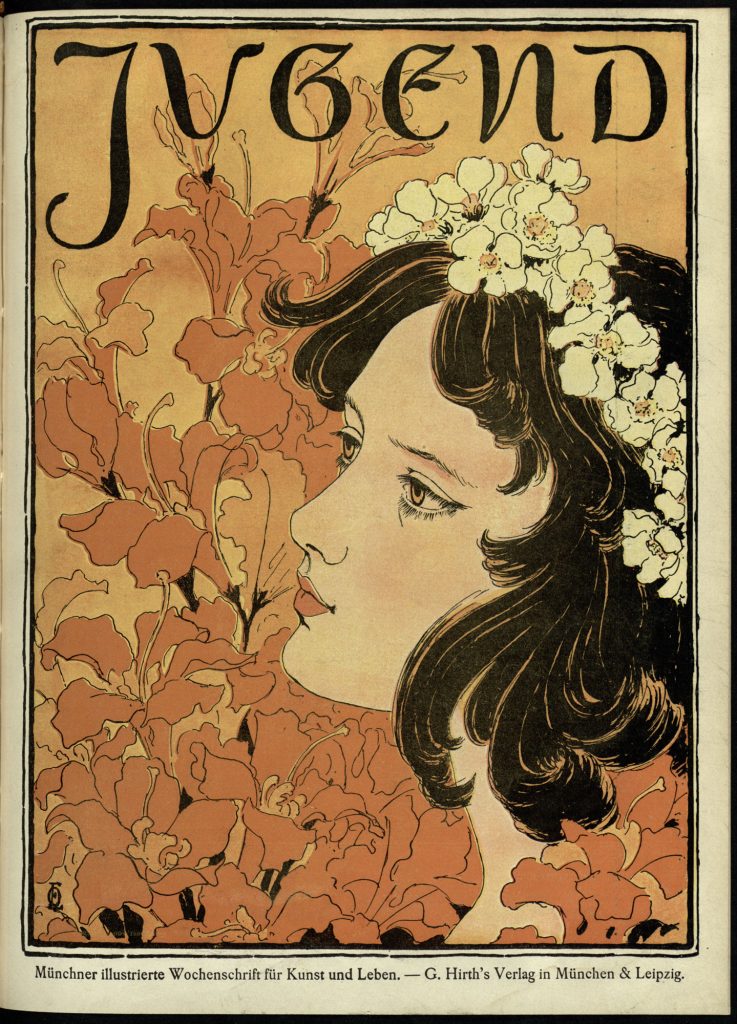

The Victorian fin de siècle was an age of tremendous change. Art, politics, science and society were revolutionised by the emergence of new theories and challenges to tradition. Arguably the most radical and far-reaching change of all concerned the role of women, and the increasing number of opportunities becoming available to them in a male-dominated world. With educational and employment prospects for women improving, marriage followed by motherhood was no longer seen as the inevitable route towards securing a level of financial security.

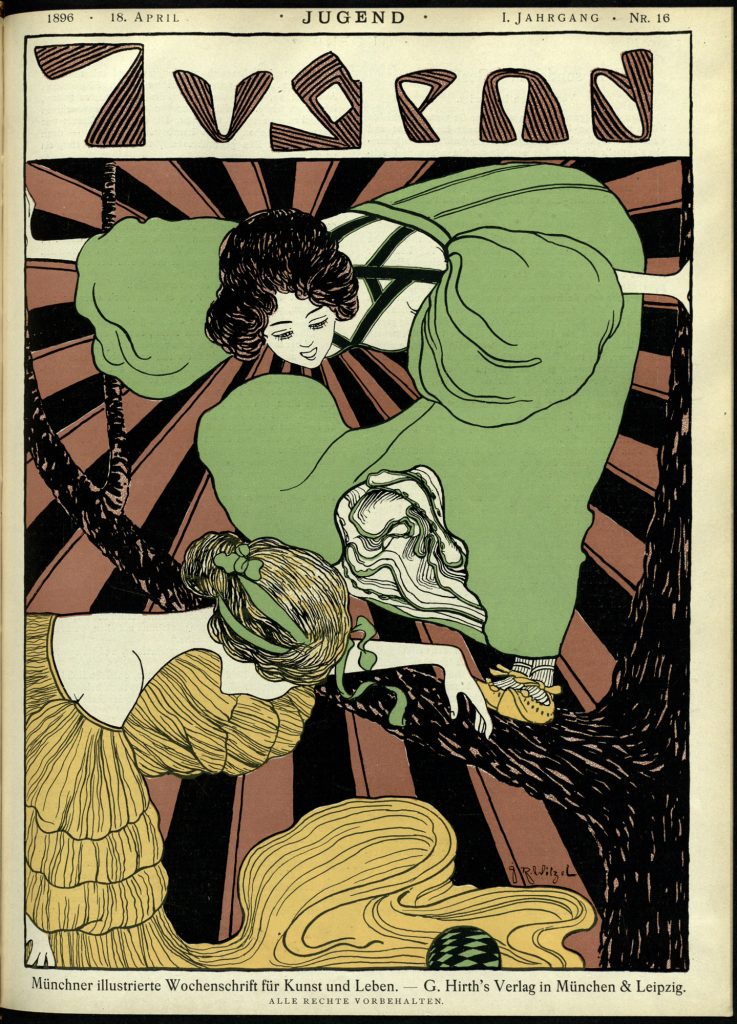

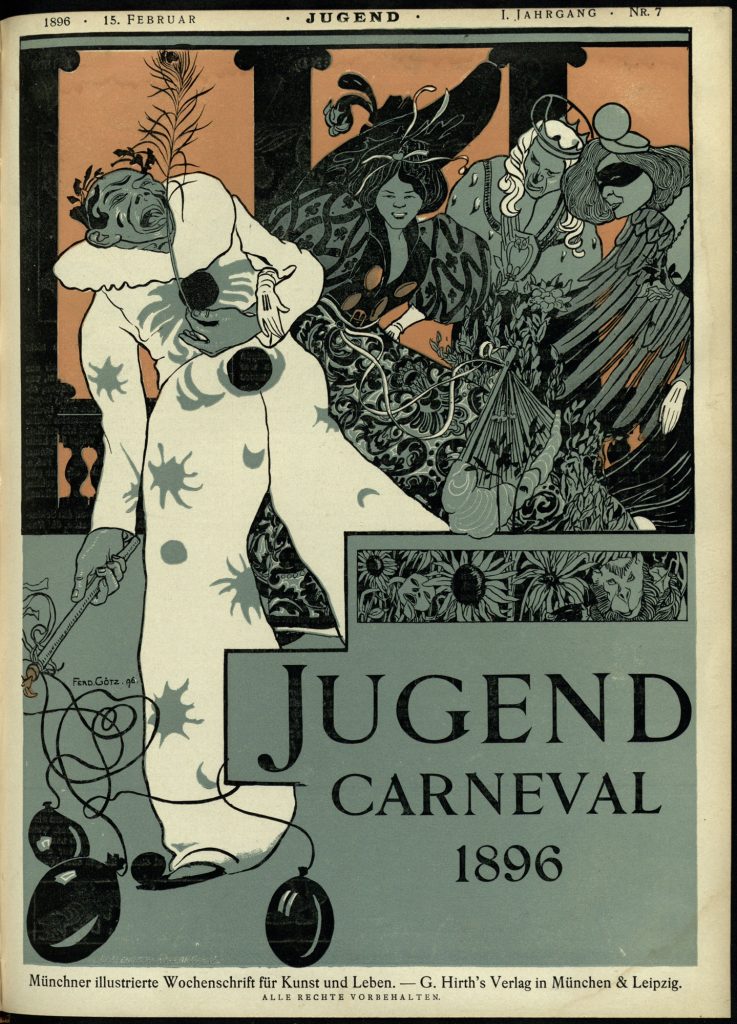

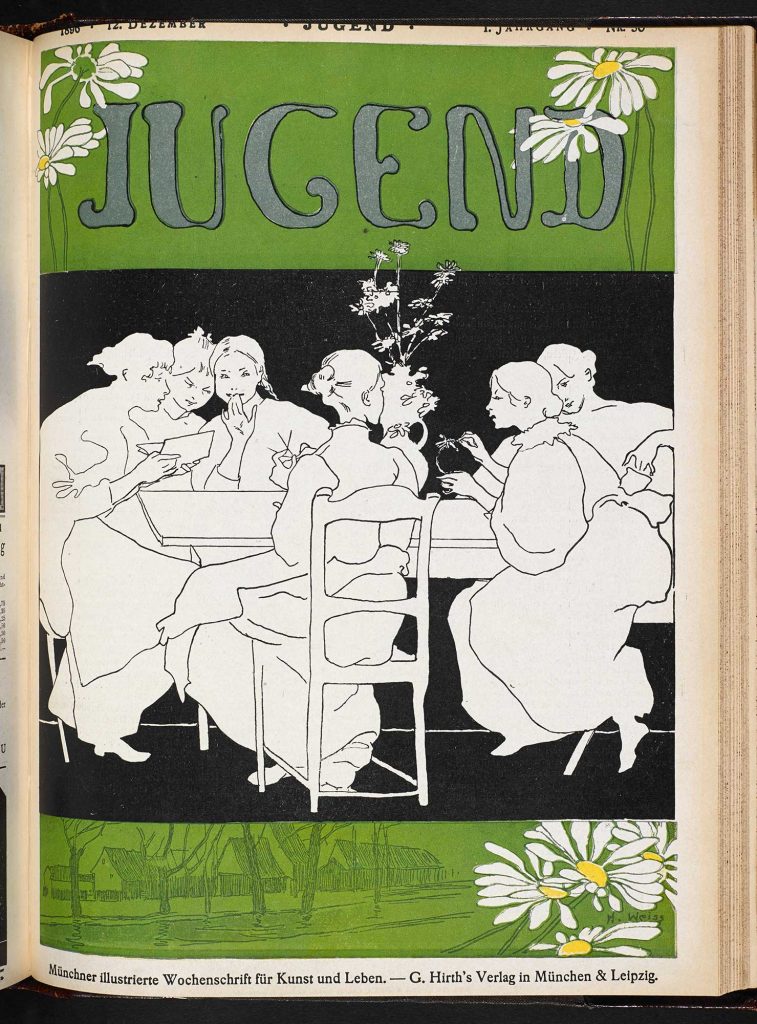

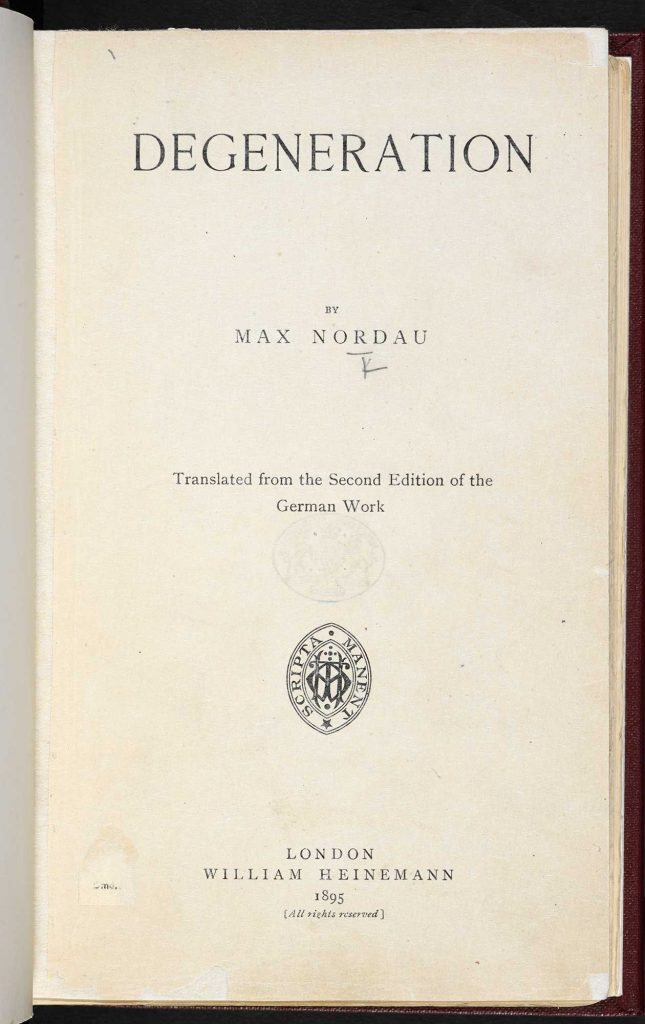

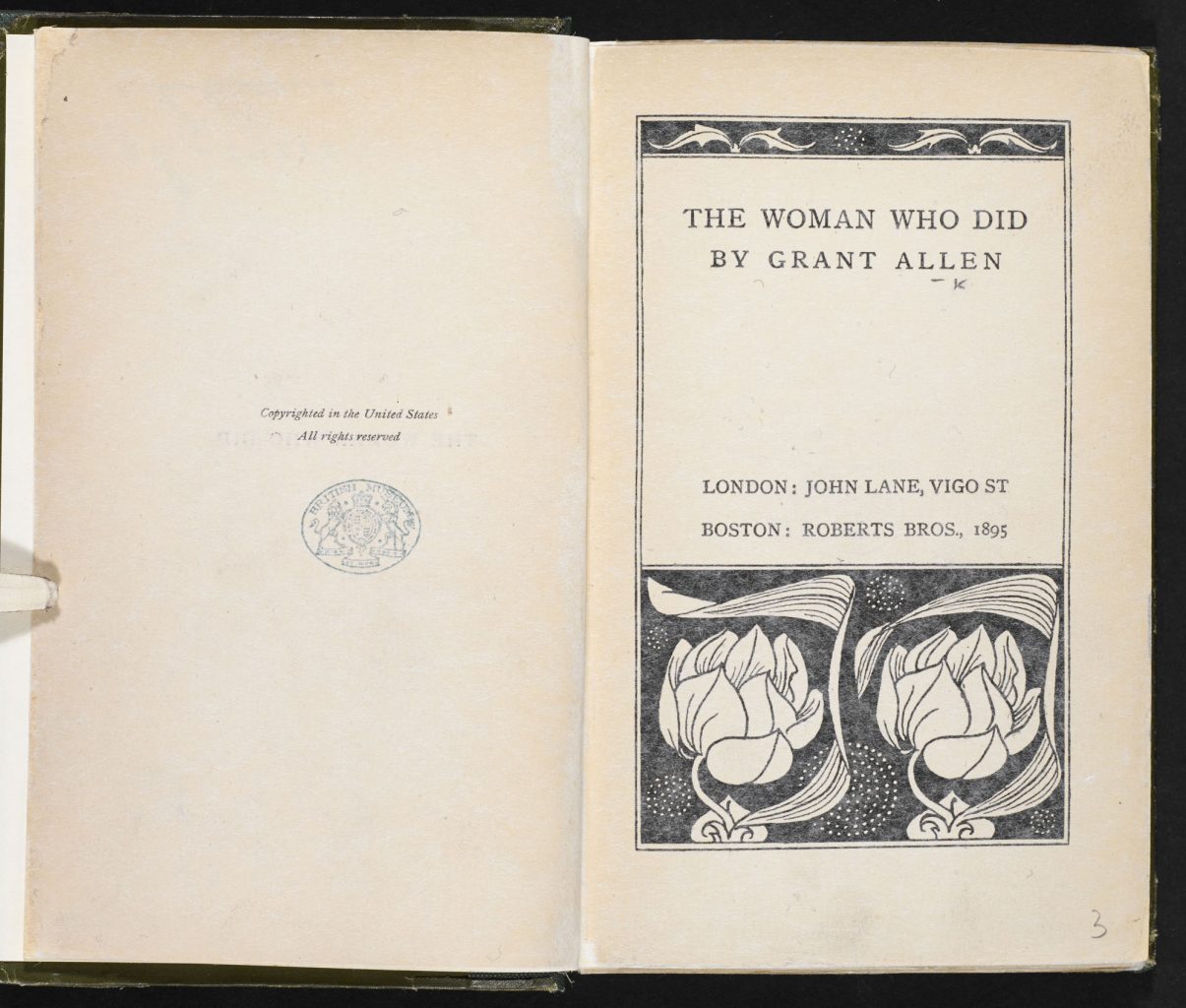

A new air of sexual freedom also emerged in the fin de siècle. Although still a controversial subject, writers such as Thomas Hardy and George Moore addressed sexual desire head on in novels such as Jude the Obscure (1895) and Esther Waters (1894). The fin de siècle emphasis on the importance of pursuing new sensations also, inevitably, led to sex and sexuality playing an increasingly important part in the search for new experiences. It is no coincidence that the New Woman and the dandy were fashionable at the same time. Just as the New Woman undermined the traditional view of the feminine, so the dandy threatened the accepted view of masculinity. Such radical changes in behaviour caused outrage, with the social critic Max Nordau denouncing the abandonment of tradition and the feminisation of men and the increasingly mannish nature of women. This he heralded as ‘The Dusk of Nations’ – the title he gave to the first chapter of his influential book Degeneration (1892). Meanwhile Punch magazine made the New Woman a figure of fun, presenting her as an embittered, over-educated spinster perpetually stuck on the shelf. [1]

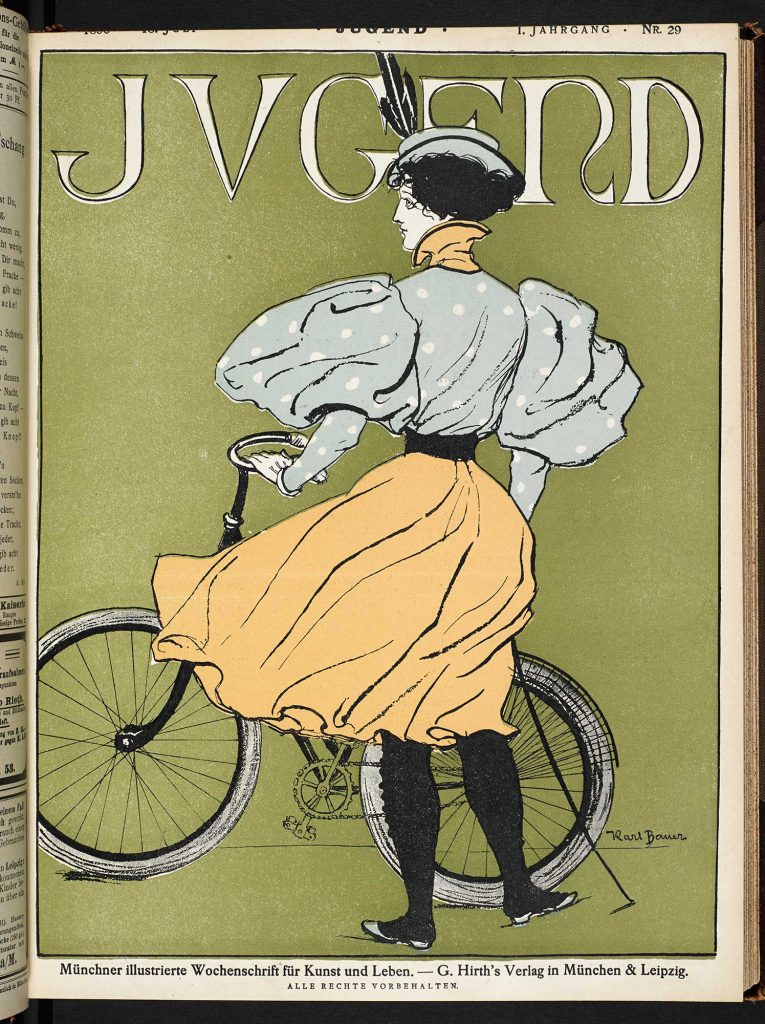

Arguments for and against the New Woman did not always follow obvious lines. Many men found the idea of women making their own way in the world both sensible and desirable, while many women – the novelist Mary Augusta Ward, who wrote under her married name Mrs Humphry Ward, being a notable example – were passionately against female emancipation and the threat it posed to the status quo of marriage and motherhood. Either way, whether viewed as a free-spirited, independent, bicycling, intelligent career-minded ideal or as a sexually degenerate, abnormal, mannish, chain-smoking, child-hating bore, the New Woman was here to stay and, admired or despised, she remained a force for change throughout the late-Victorian and Edwardian periods.

Origins of the term

The origins of the term ‘New Woman’ are disputed, but it appears to have entered the language in 1894 when it was used in a pair of articles written by the novelists Sarah Grand (born Frances Elizabeth Bellenden Clarke) and ‘Ouida’ (the pseudonym of Maria Louise Ramé) in the North American Review. Grand published an article titled ‘The New Aspect of the Woman Question’[2] from which ‘Ouida’ then extrapolated the soon to become famous phrase ‘The New Woman’ for the title of her essay.[3] The focus of Grand’s piece was particularly pertinent to the rise of the New Woman, addressing as it did the double-standards inherent in Victorian marriages, which insisted on impeccable sexual virtue on the part of the wife but not on that of the husband – a theme she later addressed in her novel The Heavenly Twins (1894). Once coined, the term became popular shorthand to describe the new breed of independent, educated women. The qualities and characteristics that came to define ‘The New Woman’ had, however, already been around for some time, as can be seen from the literature of the 1880s.

The New Woman in literature

The New Woman was a real, as well as a cultural phenomenon. In society she was a feminist and a social reformer; a poet or a playwright who addressed female suffrage. In literature, however, as a character in a play or a novel, she frequently took a different form – that of someone whose thoughts and desires highlighted not only her own aspirations, but also served as a mirror in which to reflect the attitudes of society. Early examples of the New Woman in fiction include Nora in Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House (1879), a woman who leaves her husband to pursue her own desires; Lyndall in Olive Schreiner’s The Story of an African Farm (1883) – a book that addresses themes including feminism, pre-marital sex and pregnancy out of wedlock; and Grace Melbury in Thomas Hardy’s The Woodlanders (1887), a woman whose excellent education leaves her intellectually isolated from her family and friends.

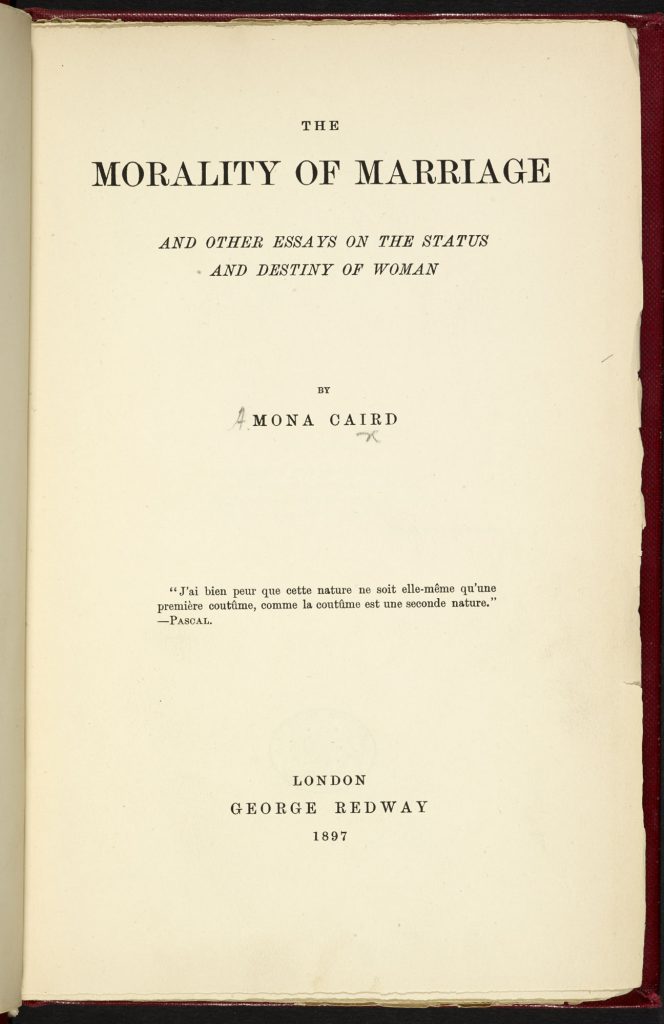

The heyday of New Woman fiction, however, took place in the mid-1890s. Sarah Grand, following on from her article ‘The New Aspect of the Woman Question’ highlighted the double-standards inherent in Victorian Society by launching an attack on the Contagious Diseases Acts of the 1860s in her book The Heavenly Twins. In the book Evadne Frayling, the central character, refuses to consummate her marriage when she discovers, on her wedding day, her husband’s dubious sexual past. The Contagious Diseases Acts had allowed for the forcible detainment of prostitutes in ‘Lock Hospitals’ while the men who frequented prostitutes, in a ghastly example of double-standards, remained at liberty to spread any disease they happened to be carrying. Grand’s 1897 novel The Beth Book addresses similar themes while also exploring the disastrous consequences for a young woman who is encouraged to make an advantageous marriage at the first opportunity rather than pursue an education and intellectual freedom.

The New Woman and sex

The traditional view of a woman’s role in Victorian society was epitomised by Coventry Patmore’s poem ‘The Angel in the House’, first published in 1854. The poem describes the author’s ideal of femininity: a loving wife devoted to her husband, a mother devoted to her children. William Acton’s observation regarding female sexuality meanwhile, published in 1862, summed up the medical man’s view of the ideal woman’s sexual desires, or rather the lack thereof:

As a general rule a modest woman seldom desires any sexual gratification for herself. She submits to her husband, but only to please him and, but for the desire of maternity, would far rather be relieved from his attention. [4]

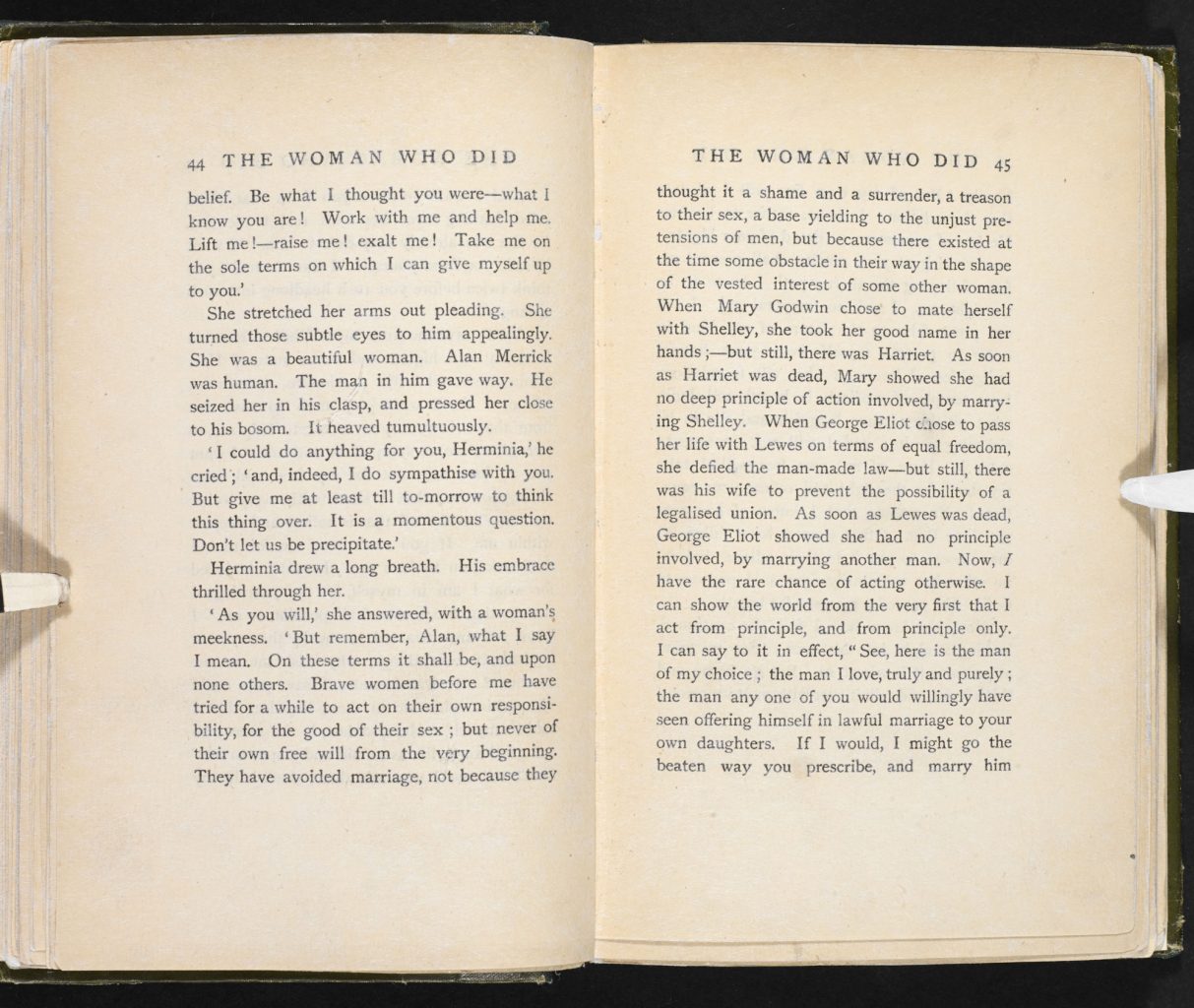

Fiction during the fin de siècle reacted against such traditional ideas in a number of different ways. Male writers tended to cast the New Woman as either a sexual predator or as an over-sensitive intellectual unable to accept her nature as a sexual being. Lucy Westenra in Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) is an example of the former, while Sue Bridehead in Thomas Hardy’s Jude the Obscure represents the latter. For Lucy Westenra the case is extreme. Even before Dracula turns her into a fully-fledged vampire, Lucy is expressing a desire for three husbands (and thus, of course, three sexual partners). Having received three proposals of marriage on the same day, she laments: ‘Why can’t they let a girl marry three men, or as many as want her, and save all this trouble?’ (ch. 5). After Dracula’s attacks, Lucy becomes a voluptuous, unnatural parody of the New Woman as sexual decadent; a figure who preys upon children, exhibiting no maternal instincts whatsoever. Lucy’s ultimate dispatch – with her husband driving a stake through her heart while his friends look on – has the horrific feel of a rape, and represents not only a terrible punishment for her sexual licentiousness, but also perhaps a punishment for her submission to the attentions of a degenerate foreign aristocrat.

The character of Mina Murray in Dracula is more subtle. She is independent and intelligent, but with her marriage to Jonathan and her willingness to play the dutiful wife, she escapes punishment. The fact Mina survives while Lucy meets such a horrific end perhaps indicates that Stoker disliked the New Woman in particular, while admiring her more traditional counterpart.

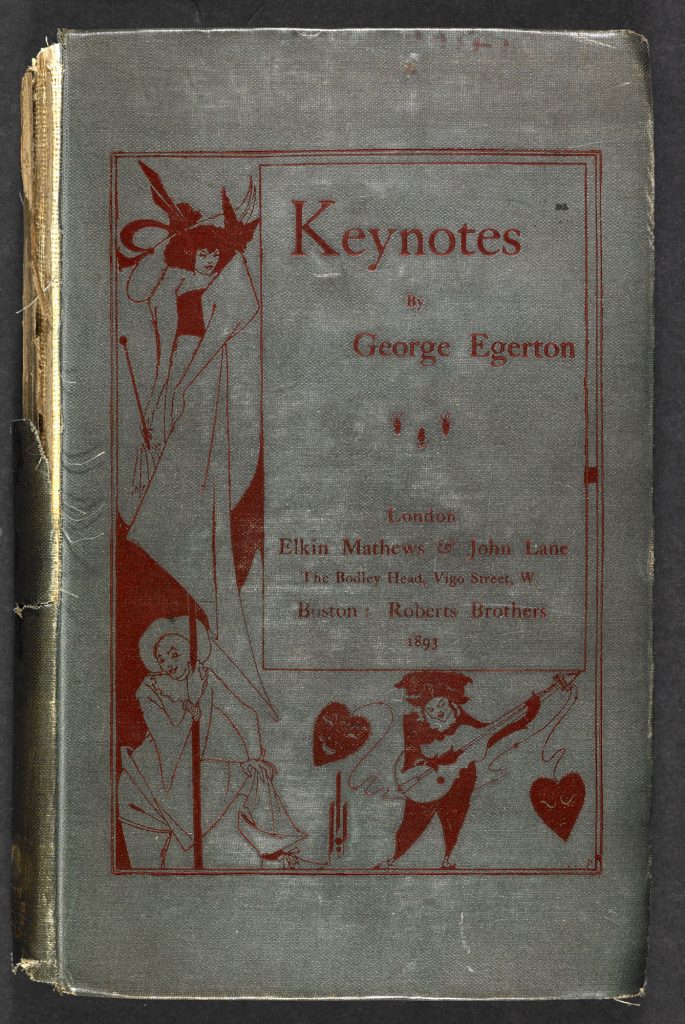

A balance to Stoker’s views of women who enjoy their sexuality can be found in the work of George Egerton (the pen name of Mary Chavelita Dunne Bright). Egerton’s short stories, especially those published in the collection Keynotes (1893), celebrated the sexually adventurous side of the New Woman in a positive fashion – as indeed did her own life. Egerton was twice married, once divorced and once widowed, and enjoyed a string of affairs.

Decline and fall

The New Woman and the Decadent were frequently linked, but the alliance was an uneasy one. Sarah Grand attacked Decadence via the disreputable figure of Alfred Cayley Pounce in The Beth Book – Pounce even works for a journal tellingly named The Patriarch. Other New Women writers however eagerly submitted stories to The Yellow Book which was viewed as the definitive Decadent publication. The Yellow Book fell from grace at the same time as Oscar Wilde. Although Wilde never contributed to The Yellow Book it was seen as somehow guilty by association. The New Woman, together with the Decadent and the dandy were caught up in the storm caused by Wilde’s fall from grace and on 21 December 1895 Punch gloated ‘THE END OF THE NEW WOMAN – The Crash has come at last’. New Woman fiction, post 1895, declined markedly but as a figure in real life, and as a prototype for virtually every feminist movement that followed, the legacy of the New Woman lives on to this day.

脚注

- Punch magazine, vol.106 (January-June 1894) contains a satirical cartoon called ‘Passionate Female Literary Types’.

- North American Review, 158 (1894) pp. 270-6.

- Ibid., pp. 610-19.

- William Acton, The Functions and Disorders of the Reproductive Organs in Childhood, Youth, Adult Age and Advanced Life Considered in the Physiological, Social and Moral Relations (London: John Churchill, 1862), pp. 101-102.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Greg Buzwell

Greg Buzwell is Curator for Printed Literary Sources, 1801–1914 at the British Library; he is also co-curator of a major exhibition on Gothic literature, Terror and Wonder: The Gothic Imagination, which ran at the Library from October 2014 to 20 January 2015. His research focuses primarily on the Gothic literature of the Victorian fin de siècle. He is also editing a collection of Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s ghost stories, The Face in the Glass and Other Gothic Tales, for publication this autumn.