Fairytale and realism in Jane Eyre

Dr Carol Atherton explores how Charlotte Brontë mixes fantasy with realism in Jane Eyre, making use of fairytale and myth and drawing on the imaginary worlds she and her siblings created as children.

Professor John Bowen explains how Charlotte Brontë combines fairytale, Gothic techniques and realism to give Jane Eyre its unique power. Filmed at the Brontë Parsonage, Haworth.

Jane Eyre is often seen as a profoundly realistic novel, drawing on Charlotte Brontë’s own experiences to paint a vivid picture of Jane’s suffering at Lowood and her struggle against the narrow role that 19th-century society allotted to women. Nevertheless, the novel also contains a strong element of fantasy. Right from the start – hidden in the window-seat, where she sits, ‘cross-legged, like a Turk’ – Jane escapes into a world of imagination, losing herself in the wild frozen landscapes of Bewick’s History of British Birds, and thinking of the fairytales and ballads told by Bessie, the nurse, on winter evenings. Fantasy is thus established as a counterpoint to Jane’s real-life privations, and as a rich source of imagery.

Rochester

One important strand of fantasy in the novel surrounds Jane’s relationship with Rochester, which is shot through with references to myth and fairytale. When Jane encounters Rochester’s dog Pilot in Hay Lane, just before she meets Rochester himself, her first thought is of the ‘Gytrash’, a mythical black dog said to haunt the deserted roads of northern England. Rochester repeatedly refers to Jane as a ‘sprite’ and a ‘fairy’, and claims that she ‘bewitched’ his horse (ch. 13). The paintings that Jane shows to Rochester – of a cormorant perched on a desolate shipwreck, the goddess Selene rising into the sky above Mount Latmos, and a ‘colossal head’ wreathed in ‘turban folds’ – are straight out of fantasy, influenced by Brontë’s knowledge of the Bible and of Greek mythology (ch.13). And the tale of the poor orphan who overcomes obstacles to marry a rich man can itself be seen as having its roots in fairytale, although what could appear as a simple rags-to-riches story is complicated by Rochester’s references to himself as an ‘ogre’ (ch. 24), the fact that Jane is emphatically not a Beauty, and the troubling fact that in the fairytale canon, the most famous imprisoner of wives is, of course, the murderer Bluebeard.

The Brontës’ childhood fantasies

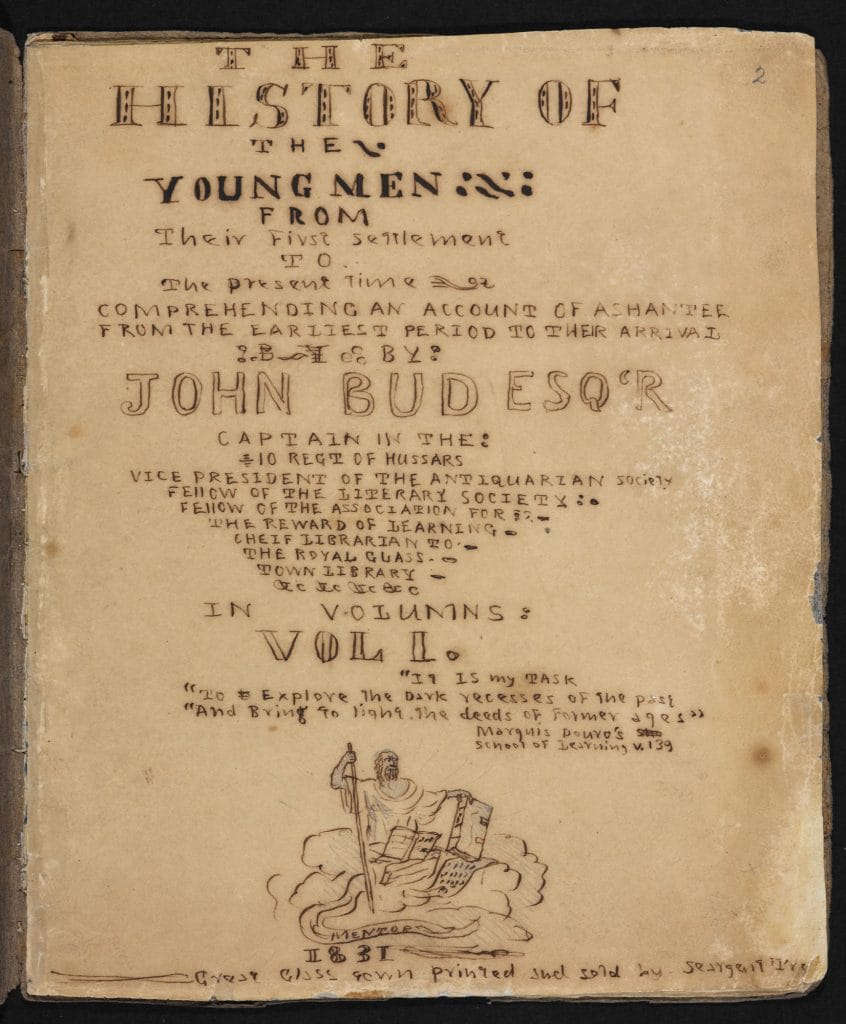

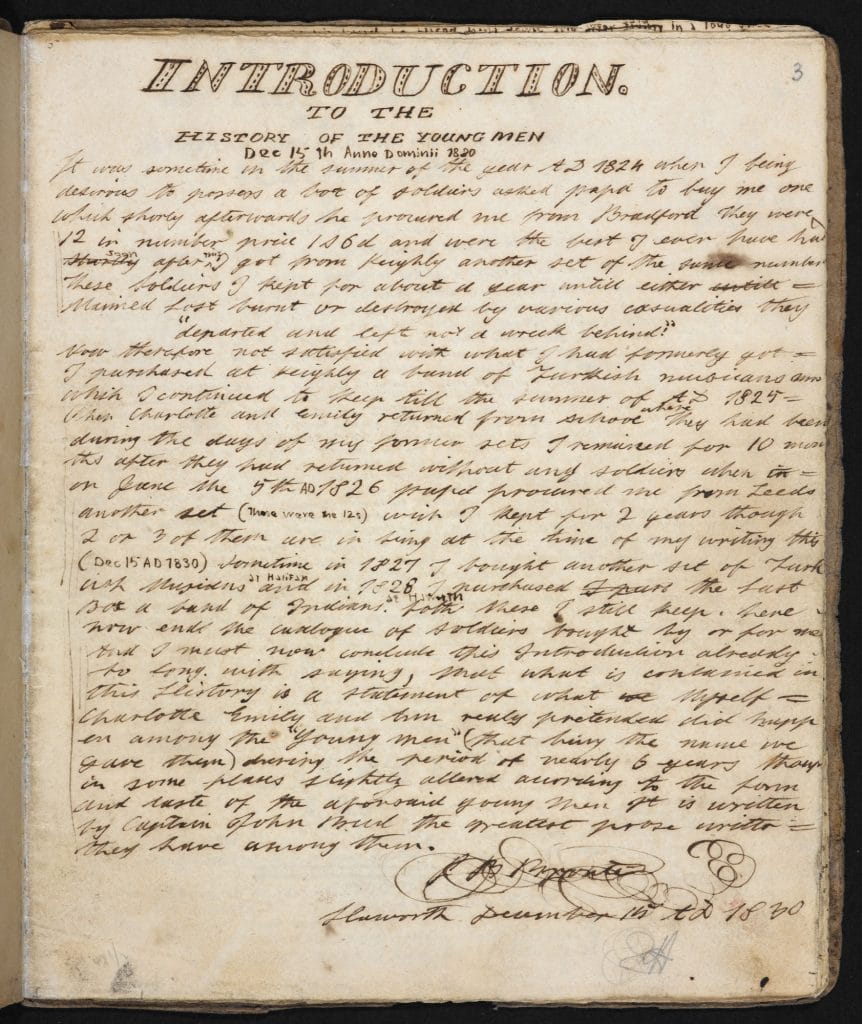

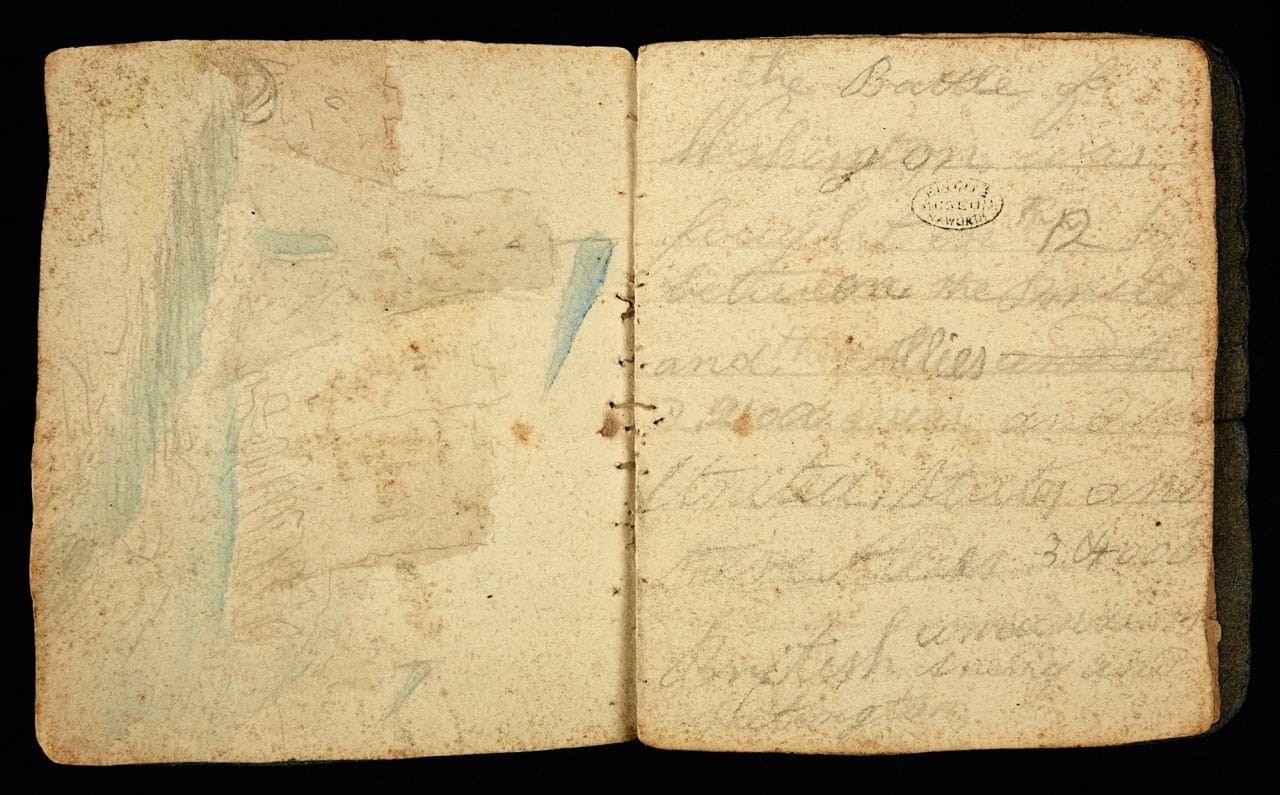

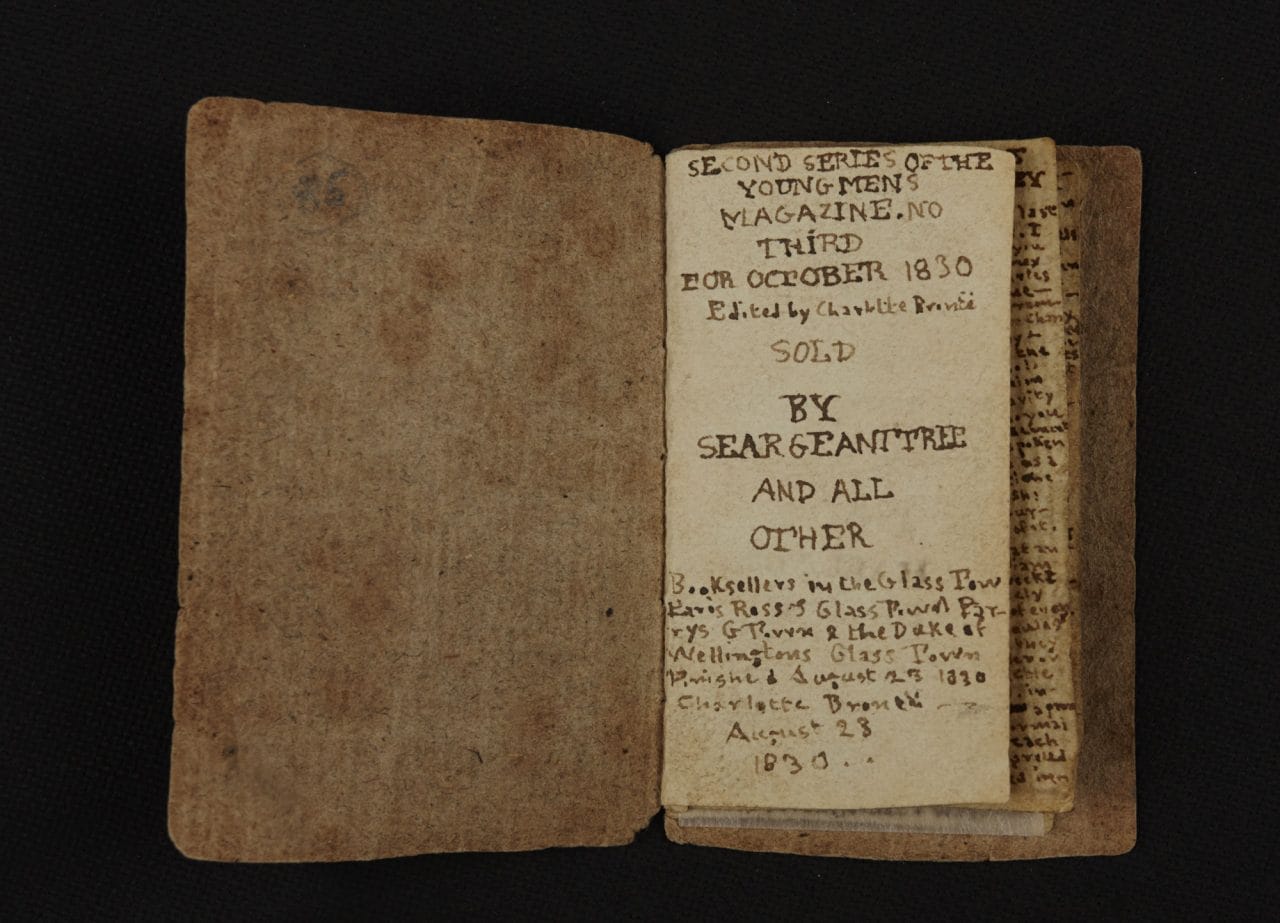

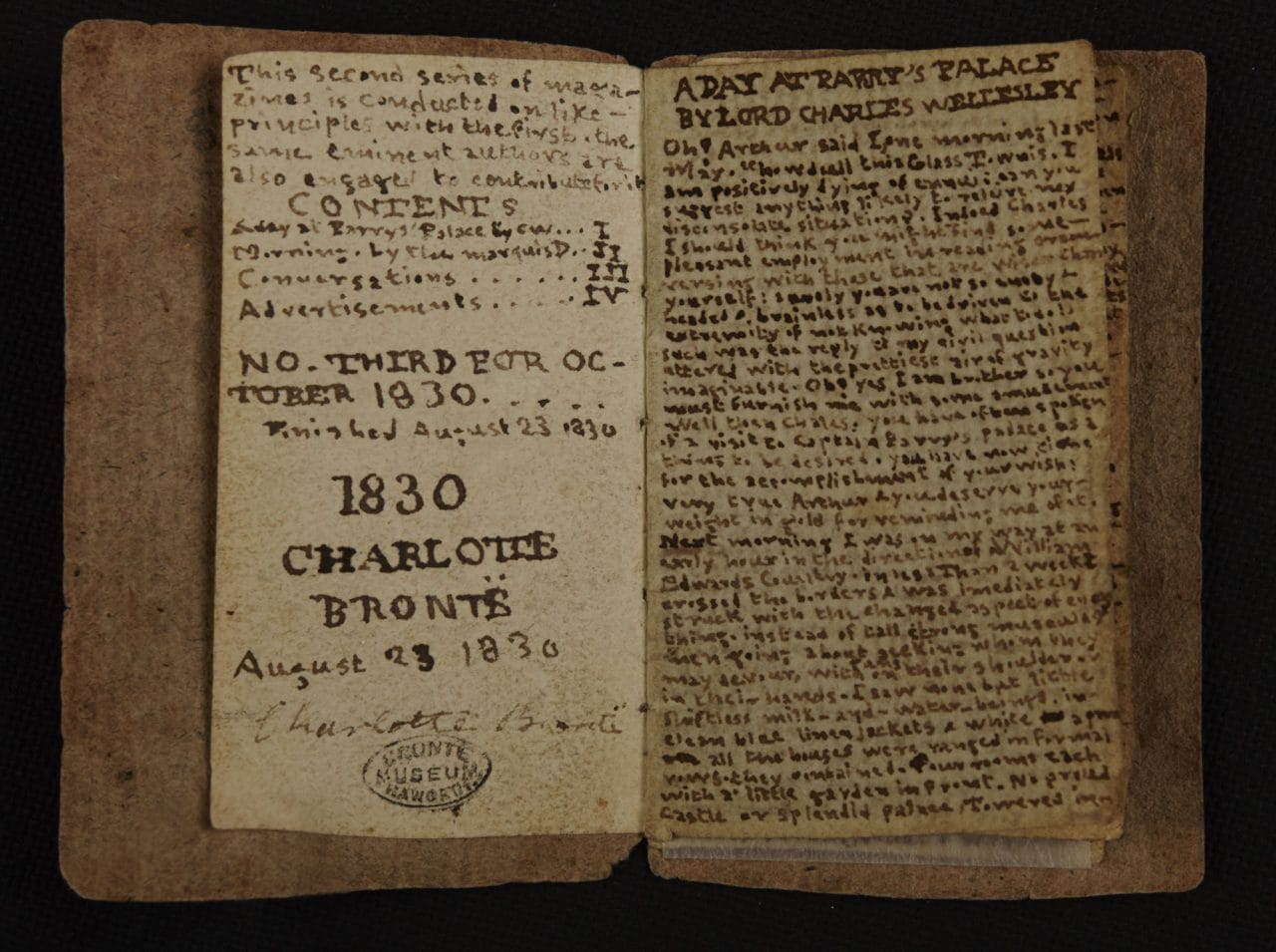

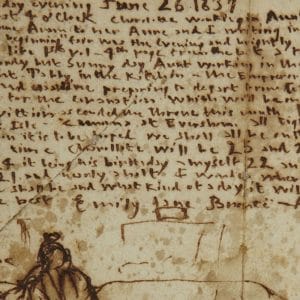

If the realistic elements of Jane Eyre can be traced back to its author’s childhood, then so can its more fantastical side. This has its roots in the ‘web’ of stories woven by the Brontë children. These began, famously, when the Revered Brontë brought home a box of soldiers from a trip to Leeds in 1826. Charlotte described this event in her idiosyncratic spelling in her ‘History of the Year’:

Emily and I jumped out of bed and I snat[c]hed up one and exclaimed this is the Duke of Wellington it shall be mine!! When I said this Emily likewise took one and said it should be hers when Anne came down she took one also. Mine was the prettiest of the whole and perfect in every part Emilys was a Grave looking ferllow we called him Gravey. Anne’s was a queer little thing very much like herself. he was called waiting Boy Branwell chose Bonaparte.

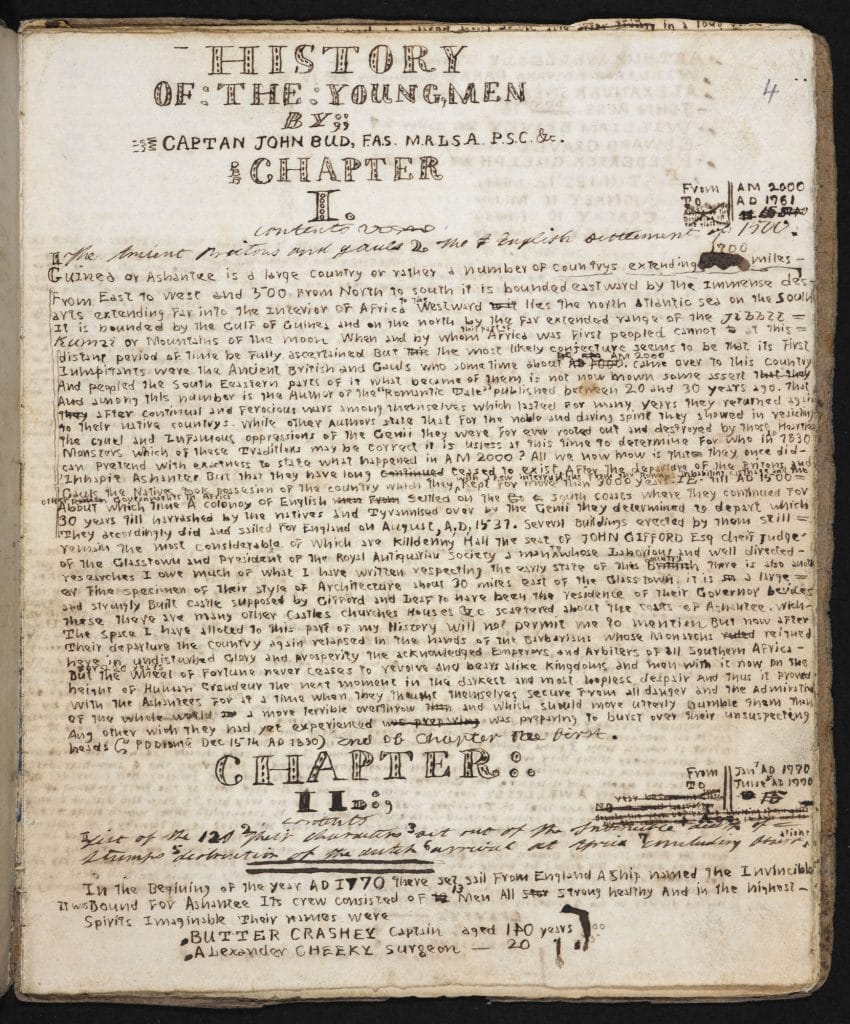

These soldiers became the basis for the imaginary worlds of Angria and Gondal that absorbed so much of the children’s attention. Set in Africa and the South Pacific, and featuring a cast of characters based on contemporary political figures such as Wellington (Charlotte’s hero) and Napoleon, and influenced by the writings of Byron and Scott, the Angria stories (created by Charlotte and Branwell) and their Gondal counterparts (the invention of Emily and Anne) were an early education in writing about political intrigue and tempestuous romance. Indeed, critics such as Christine Alexander have argued that they allowed their authors to explore emotions that had few other outlets. They were written up into tiny books and absorbed their authors well into adulthood, occupying a space in their imaginations that was in some ways even more vivid than reality.

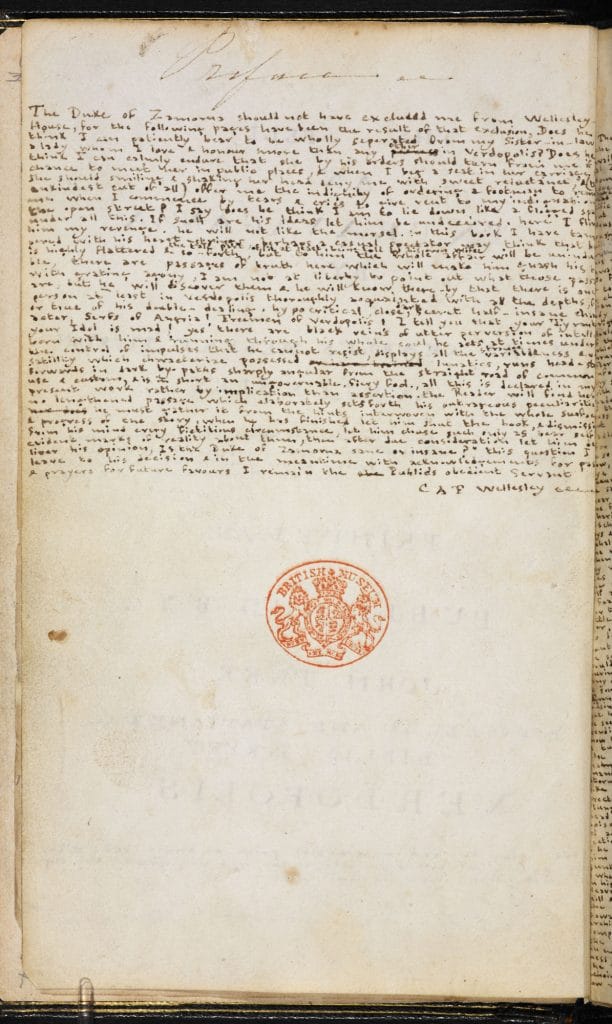

As an adult, Charlotte struggled to detach herself from the world of Angria, which increasingly became the possession of Branwell. Nevertheless, many of the fantastical elements of Jane Eyre have their roots in Angria; and the character of Rochester – dark, complex and brooding – is a direct descendant of the Angrian hero the Duke of Zamorna. An awareness of fantasy is, therefore, essential to an understanding of both Jane Eyre and the imagination that shaped it, adding another dimension to a novel that is grounded so firmly in reality.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Carol Atherton

Carol Atherton is Head of English at Spalding Grammar School in Lincolnshire. She has worked with a number of organisations, including NATE, the British Library, the Poetry Archive and the British Council, and was made a Fellow of the English Association in 2009. A specialist in literary theory and pedagogy, she has written widely on the teaching of English Literature, curricular reform and the nature of disciplinary knowledge.