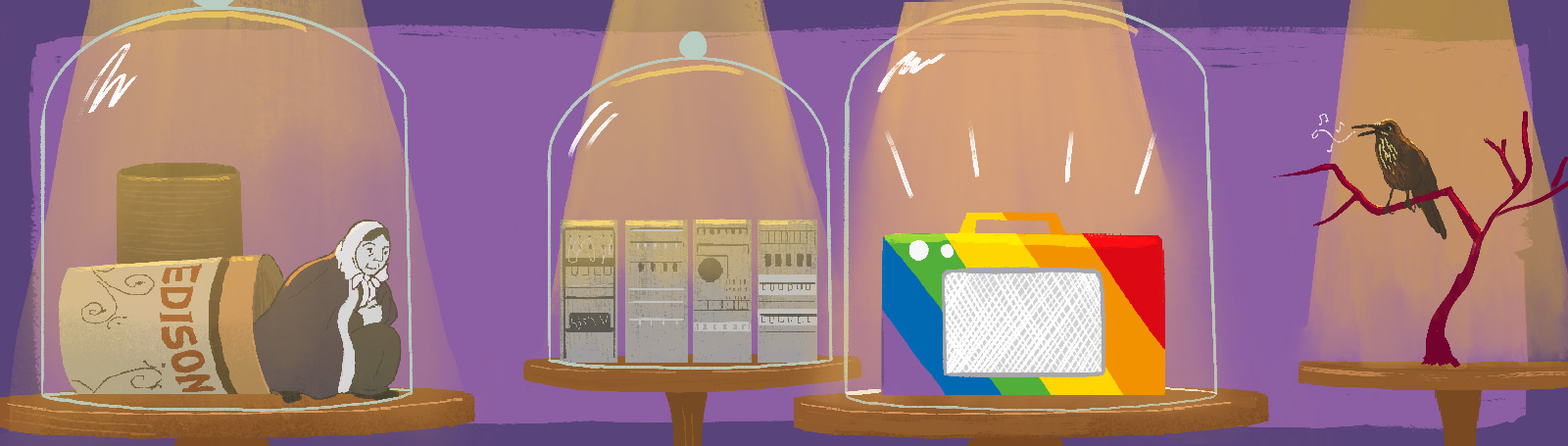

First, rare and only sound recordings from the British Library’s collections

From the first melody produced by a computer, to the only recording of Florence Nightingale’s voice, and the last call of a Kauai O’o A’a. Harriet Roden explores the first, rare and only sound recordings housed by the British Library.

Wax cylinders, cassettes and LPs line the shelves of the British Library’s Sound Archive. Their contents reveal the ever-changing nature of our world from the last 130 years: from our tastes in popular music, to a natural world forever impacted by environmental change.

Discover some of the first, rare and only recordings housed by the British Library.

1. The first wildlife recording

When Ludwig Koch turned 8 years old in 1889, his father gifted him an early Edison phonograph. Unknowingly, Koch became a pioneer in the recording of nature sounds when he recorded his pet Shama, a small white, black and orange bird originating from Southeast Asia.

This recording is comprised of an interview with Koch, and the first-known recording of a captive bird.

Ludwig Koch on the recording a White-rumped Shama in 1889

Title: Ludwig Koch on the recording a White-rumped Shama in 1889 Creator: Ludwig Koch Held by: British Library Shelfmark: C1398/0054 Copyright: Audio: © BBC; Image: Public Domain

This recording comprises an interview with Ludwig Koch (1881–1974) and a recording of a captive bird that he made when he was eight years old.

Who was Ludwig Koch?

As a child, Koch was given an early Edison phonograph by his father. Unknowingly, and at the age of just eight, he became a pioneer in the recording of nature sounds. This recording of the song of a captive white-rumped shama (Kittacincla malabarica) in 1889 is the first-known recording of bird song.

Koch went on to have an illustrious career, establishing himself as a leading figure in the world of natural history sound recording from the 1930s. Whilst recordings of captive birds were available commercially in the first decade of the 20th century, there were many technical and logistical challenges in recording wild animals in their natural habitat. Koch worked with the evolutionary biologist Sir Julian Huxley to publish Songs of Wild Birds in 1938. This sound book meant that for the first time people could listen to the songs and calls of Britain’s most common birds in their own homes.

His work with the BBC brought the sounds of the natural world to thousands of listeners across the UK.

How does the phonograph work?

Sound creates vibrations that are collected by a horn. The phonograph’s horn was attached to a diaphragm which in turn was attached to a stylus. When the horn collects sounds, it causes the diaphragm to vibrate and the stylus is pressed into the cylinder. A recording is made when the cylinder is rotated and the stylus moves up and down to cut a groove representing the original sound.

At the time of Koch’s early recordings, an Edison phonograph had been upgraded to use wax cylinders. Wax cylinders improved the stability of the sound that could be recorded, and had a longer lifespan than the original tinfoil recordings.

The Early Wildlife Recordings collection

The collection presents an assortment of species and habitat recordings that were produced during the first half of the 20th century. The majority of the recordings were originally released on gramophone records, presented in box sets and accompanied by illustrated literature that provided the listener with information about the creatures they were hearing.

Material from two pioneer wildlife recordists, Ludwig Koch and Carl Weismann, dominates this selection of sounds.

2. The only recording of Florence Nightingale

In May 1890, many veterans of the Charge of the Light Brigade in the Crimean War were left destitute. Parliament offered no assistance and so, in response, St James’s Gazette established the Light Brigade Relief Fund.

Three charity records were made on wax cylinders in order to raise funds for the campaign.

The first was from Martin Lanfried, a trumpeter sounding the charge as heard at Balaclava. The second was Alfred Lord Tennyson, reading his poem The Charge of The Light Brigade. And finally, there was Florence Nightingale sending blessings to her comrades.

This is the only recording of Florence Nightingale’s voice.

Florence Nightingale’s appeal in aid of the Light Brigade Relief Fund

Title: Florence Nightingale’s appeal in aid of the Light Brigade Relief Fund Creator: Florence Nightingale Held by: British Library Shelfmark: C1693/1 Copyright: Public Domain

Florence Nightingale (1820–1910) served as a nurse in during the Crimean War where her experiences led to pioneering work in improving medical care in the army and the professional training of nurses.

Nightingale made this recording to support the Light Brigade Relief Fund on 30 July 1890 at her home in London. In it, Nightingale delivers a message to the veterans of the Light Brigade, who fought at the Battle of Balaclava in 1854 during the Crimean War.

Originally recorded on wax cylinder, the speech was released commercially as a 78rpm disc in 1935, twenty five years after her death. This transfer has been made from the original cylinder, which was found to hold two different ‘performances’ of the same short speech.

Her famous words read, ‘When I am no longer even a memory, just a name, I hope my voice may perpetuate the great work of my life. God bless my dear old comrades of Balaclava and bring them safe to shore. Florence Nightingale.’

What was the Light Brigade Relief Fund?

The Light Brigade Relief Fund was set up in response to a public scandal that erupted in May 1890, when it was discovered that many veterans of the charge of the Light Brigade were destitute. The Secretary for War stated in Parliament that he could not offer assistance.

In response, the St. James’s Gazette set up the Light Brigade Relief Fund. Colonel Gouraud, Thomas Edison’s representative in Britain, supported the fundraising efforts by making three sound recordings: this speech by Nightingale, Alfred Lloyd Tennyson reading The Charge of the Light and Martin Lanfried, trumpeter and veteran, sounding the charge as heard at Balaclava.

3. The first recording of computer-generated music

Alan Turing was a mathematician, cryptographer and pioneer of computer science – who is perhaps best known for his work, during the second world war, in breaking the German Enigma code at Bletchley Park. During the 1950s he had established the Computer Machine Laboratory in Manchester.

Filling much of the ground floor of the lab, a gigantic computer had been programmed by Turing to emit a short pulse of sound which indicated what was going on in the computer. For instance one note for ‘job finished’, another for ‘error’.

The first person to program the first complete piece of music using Turing’s computer was schoolteacher Christopher Strachey. In 1951, a BBC outside broadcast unit used a portable acetate disc cutter to capture the three melodies programmed by Strachey and played by the computer.

Earliest known recording of computer-generated music

Title: Earliest known recording of computer generated music Creator: N/A Held by: British Library Shelfmark: C1467/5 Copyright: Audio: Engineering: © Jack Copeland; © Jason Long

In 1951, a BBC outside broadcast unit used a portable acetate disc cutter to capture three melodies played by the computer at Alan Turing’s Computing Machine Laboratory in Manchester. This is the first known recording of computer-generated music.

How did a computer begin to generate music?

Alan Turing was a mathematician, cryptographer and pioneer of computer science – who is perhaps best known for his work, during the second world war, in breaking the German Enigma code at Bletchley Park. During the 1950s he had established the Computer Machine Laboratory in Manchester.

Filling much of the ground floor of the lab, a gigantic computer had been programmed by Turing to emit a short pulse of sound which indicated what was going on in the computer. For instance one note for ‘job finished’, another for ‘error’.

It was not until schoolteacher Christopher Strachey approached Turing that the first complete piece of music was programmed on the computer. With access to the lab for one night only, Strachey worked with the computer. In the morning, to onlookers’ astonishment, the computer raucously hooted out the National Anthem.

What can be heard in this recording?

This recording features three melodies. The first is the national anthem God Save the King, followed by the nursery rhyme Baa Baa Black Sheep and then Glenn Miller’s popular jazz classic In The Mood. Between each, an engineer comments on the machine’s performance.

The recovery of this recording

Today, all that remains of the recording session is a 12-inch single-sided acetate disc, cut by the BBC’s technician while the computer played. However, the pitches were not accurate in the recording and only provided an impression of what the computer may have sounded like.

Jack Copeland and Jason Long worked to decipher the recording and reproduce the original sound of the computer.

4. A broadcast from Gaywaves, Britain’s first Gay radio program

In the 1980s, London’s radio waves were dominated by BBC Radio London, Capital Radio and LBC. Our Radio was born from a campaign for equality of access for marginalized voices, and the need for dedicated community-based programming. After purchasing a pair of transmitters in February 1982, the station began illegally broadcasting one night per week with a small roster of programs aimed at diverse interest groups and minority communities.

Gaywaves joined the roster in May 1982 as a program ‘run by and for gay men’. The show was recorded and edited on tape, then broadcast by Our Radio every Wednesday night until March 1983.

Gaywaves broadcast, 2 February 1983

Title: Gaywaves broadcast, 2 February 1983 Creator: N/A Held by: British Library Shelfmark: C586/365 Copyright: Audio: © Gary James; We have been unable to locate the other copyright holders for Gaywaves. Please contact copyright@bl.uk with any information you have regarding this item.; Image: © Gary James

This is an excerpt from the February 1983 broadcast of Gaywaves, a program from the pirate radio station Our Radio.

Gaywaves & Our Radio

In the 1980s, London’s radio waves were dominated by BBC Radio London, Capital Radio and LBC. Our Radio was born from a campaign for equality of access for marginalized voices, and the need for dedicated community-based programming. After purchasing a pair of transmitters in February 1982, the station began illegally broadcasting one night per week with a small roster of programs aimed at diverse interest groups and minority communities.

Gaywaves joined the roster in May 1982 as a program ‘run by and for gay men’. The show was recorded and edited on tape, then broadcast by Our Radio every Wednesday night until March 1983.

In this edited excerpt, you can listen to:

‘Anvil Chime’, Philip Cox’s alter ego, welcome listeners to the week’s program,

Comedy skits about current affairs,

And a news bulletins on activities of the Hackney Lesbian and Gay Action Group.

The Philip Cox ‘Gaywaves’ Collection

Philip Cox was the gay rights activist, and supporter of the anti-nazi league and anti-nuclear power movement, who founded Gaywaves alongside Gary James and Neil Hoechst.

The Philip Cox ‘Gaywaves’ Collection comprises of mainly off-air recordings made between 1979 and 1990, including recordings made in 1982-1983 for use in production of Gaywaves, the first British radio programme produced by and for gay men, broadcast from the pirate radio station Our Radio. The collection includes many programmes relating to HIV and AIDS and gay and lesbian issues. The collection was gifted to the British Library after Cox’s death in 1992.

Bibliography

Wilson, P. & Linfoot, M. ‘Gay waves: Transcending Boundaries – the Rise and Demise of Britain’s First Gay Radio Program’. Transnationalizing Radio Research: New Approaches to an Old Medium, edited by Follmer, G., Badenoch, A., (2018), pp.73-80.

James, G., ‘Phil Cox – a tribute’, [accessed August 2020], <https://bangagong.co.uk/bangagong.co.uk/Phil_Cox_-_A_Tribute.html>

5. A rare interview with jazz musician Champion Jack Dupree

‘Champion Jack’ Dupree (1910-1992) was a blues and boogie-woogie pianist and singer from New Orleans. This 1968 interview gives a fascinating insight into his life as a blues musician, amongst various other professions. As a master musician, Dupree can be heard playing the piano throughout the interview.

He reminisces on how he came to learn piano from a young age while living in the same orphanage alongside Louis Armstrong. Dupree goes on to discuss how he gained his nickname ‘Champion Jack’ from becoming as a successful prize fighter in Chicago before enlisting in the US navy during the second world war, which resulted in him spending two years as a Prisoner of War in Japan. It was not until after his release that he decided to become a professional musician in spite of no formal musical education. He later moved to Halifax in Yorkshire, England, with his wife, where this interview was recorded.

Dupree gives a moving description of what the blues means to him, calling it a ‘medicine’:

when you have been living a slave life all your life and to be free but when you hear these blues playing it make you think way back and it’s a bad life you think of. That’s what makes good blues. But if you’ve never had no miserable life you cannot do it, nobody that never lived bad cold make no good blues … it’s always a life story, it’s not just playing.

Champion Jack Dupree discusses his life and career as a musician

Title: Champion Jack Dupree discusses his life and career as a musician Creator: Champion Jack Dupree, James Hogg Held by: British Library Shelfmark: C122/312 Copyright: Audio: © Champion Jack Dupree © James Hogg © BBC (C122/312 T1); Image: Photographed by Heinrich Klaffs and licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

William Thomas ‘Champion Jack’ Dupree (1910–1992) was a blues and boogie-woogie pianist and singer from New Orleans. This recording is of James Hogg’s 1968 interview with him for BBC Radio 4; it gives a fascinating insight into his life as a blues musician, just one of his various professions.

The interview was recorded on 4 January 1968 at Dupree’s home in Halifax, West Yorkshire. It was broadcast on 6 January 1968 on the BBC Radio 4 programme It’s Saturday. Dupree can be heard playing the piano throughout the interview.

In this interview Dupree discusses his life and work. He reminisces on how he came to learn piano from a young age while living in the same orphanage as Louis Armstrong after his parents were murdered by the Ku Klux Klan when he was just a year old. Dupree goes on to discuss how he gained his nickname ‘Champion Jack’ from becoming a successful prize-fighter in Chicago before enlisting in the US Navy during World War Two, a decision which resulted in him spending two years as a prisoner of war in Japan. It was not until he was released that he decided to become a professional musician in spite of no formal musical education. He later moved to Halifax in Yorkshire, England, with his wife.

6. The last call of the Kauai O’o A’a

On the Hawaiian island of Kauai, there lived the O’o A’a (Moho braccatus) a small, honey-eating songbird.

The O’o A’a’s song can no longer be heard in the wild, as the species was declared extinct in 2000. This was due to largescale habitat loss and the introduction of non-native species.

In 1983, the conservationist John Sincock recorded the mating call of the last know O’o A’a bird in existence. He had lost his mate the year before during Hurrican Iwa and so his calls sadly received no response.

Kauaʻi ʻōʻō in Hawaii, 1983

Title: Recording of the last known Kauai O’o A’a bird, 1983 Creator: N/A Held by: British Library Shelfmark: WS3398 C2 Copyright: Audio: © John Sincock; Image: © Courtesy of The Smithsonian

This recording, made by John Sincock in 1983, features the mating call of the Kauai O’o A’a bird.

Where is Kauai?

Kauai is one of the many islands making up the Hawaiian archipelago in the Central Pacific. Often called the ‘Garden Island’, Kauai’s landscape features valleys, mountains and cliffs, as well as tropical rainforests, rivers and waterfalls.

What is the O’o A’a bird?

The Kauai O’o A’a (Moho braccatus) was a small, honey-eating songbird.

Sadly, the O’o A’a’s song can no longer be heard in the wild, as the species was declared extinct in 2000. This was due to large-scale habitat loss and the introduction of non-native species, such as the black rat and disease-carrying mosquitoes.

The recording captures the song of the last known O’o A’a bird in existence. He was a part of the last mating pair, but the year before had lost his mate during Hurricane Iwa.

Who made this recording?

This recording was made by John Sincock, a conservationist who worked to establish a survey of Hawaiian birds from the 1960s.

Banner image © Laura White

撰稿人: Harriet Roden

Harriet Roden is a content producer specialising in bringing archival collections to life for a range of audiences. Since 2019, Harriet has worked alongside colleagues to deliver the digital engagement strategy for the Unlocking Our Sound Heritage project, which aims to preserve and provide access to thousands of the UK’s rare and unique sound recordings.