Freedom or oppression? The fear of dystopia

Mike Ashley considers how British, Russian and American writers created repressive imaginary worlds and totalitarian regimes in order to explore 20th-century political concerns.

The word most commonly used to describe the opposite of utopia is ‘dystopia’, though when it was coined by John Stuart Mill in a speech in the House of Commons in 1868 it was not quite in the sense we use it now. Mill was reflecting on the impossibility of establishing a utopia because the basis of its economy and social development was subject to natural laws that cannot be influenced by human will, meaning that all utopias have a built-in inevitability of failure. He thus dismissed all utopian thinkers as dystopian, because their ideas were too flawed to be practical.

It is ironical, therefore, that the word dystopia has come to represent a society in which individuals are repressed, personal freedoms lost and creativity stifled. A dystopia presents the inhumanity of the soulless state machine against the hopes and aspirations of humanity. It’s something we will all recognise.

The dystopian novel can be considerably more effective than the utopian. The utopian novel, in looking at mankind’s ideals and how a perfect society might be achieved, will always encounter hurdles that must be overcome in seeking how to satisfy everyone, or at least the majority. The dystopian novel, on the other hand, readily provides a graphic warning of the consequences of going in a certain social, political or technological direction, and can do so with startling imagery that resonates with the reader.

Early dystopias

The dystopia can be traced back at least as far as Émile Souvestre’s Le monde tel qu’il sera (‘The World as It Will Be’, 1846) which foresaw how commercialism would make humanity a slave to the corporate or political machine. Ignatius Donnelly foresaw in Caesar’s Column (1890) how state control could easily fall into the hands of corrupt individuals. Jack London took this further in The Iron Heel (1907), where a capitalist oligarchy seeks to gain absolute power in America but is defeated by the socialists – both sides using similar techniques – until a form of socialist utopia prevails.

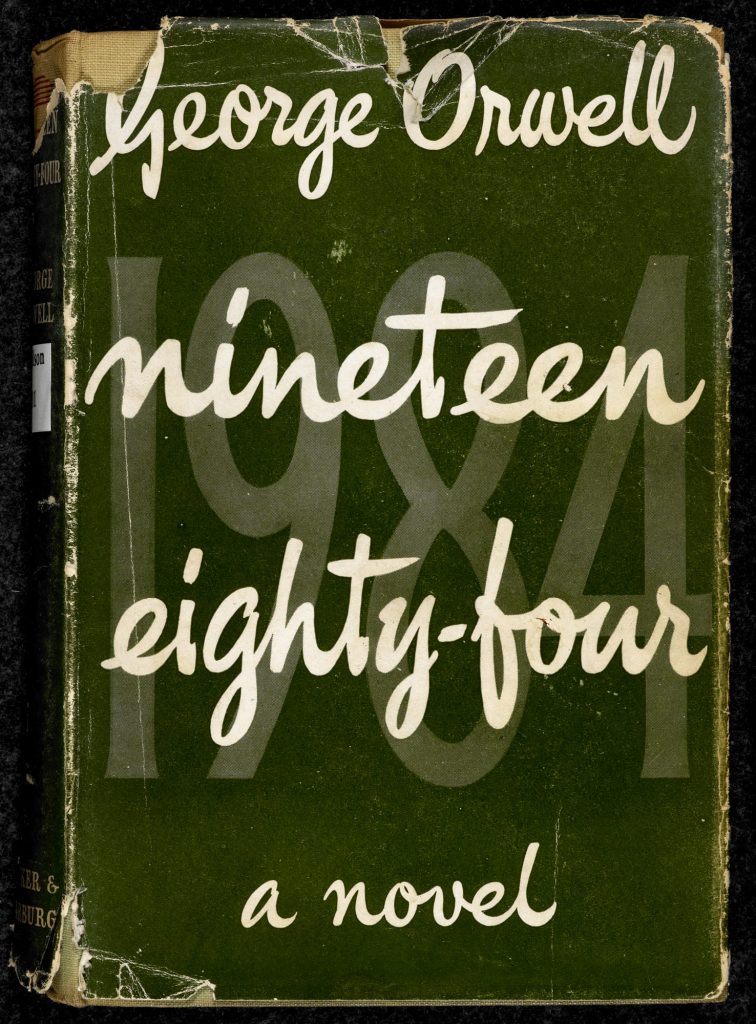

Nineteen Eighty-Four

The most famous all of dystopias is George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) which, even though the year represented by the book is now almost as far in our past as it was in Orwell’s future, still conjures up images of a totally oppressive regime in which humans have no individuality. The novel is set in one of three global totalitarian super-states where the population, which must obey a strict set of codes, is constantly monitored by ‘Big Brother’ and the Thought Police. Even thinking outside these codes is punishable. The main character, Winston Smith, works for the state, doctoring photographs and revising the historical record. Personal relationships are forbidden, and so when Smith falls in love he is punished, forced to betray his lover and brainwashed so that he again loves Big Brother.

Russian dystopias

Orwell was inspired to write Nineteen Eighty-Four by Yevgenii Zamyatin’s My (We), which had been written in 1920 and was officially banned by the Soviet Union after an abridged version was serialised in 1927. The full version was not published there until 1988. An English-language edition was published in the USA in 1924, without Zamyatin’s permission, and it was this version that Orwell read. The book takes place several centuries in the future after a 200-year war has wiped out most of humanity. It is set in a highly regimented city-state encircled by the ‘Green Wall’, which is supposed to keep out the post-apocalyptic world. Everything in the future is state controlled, including when you eat and when you can have sex. No one is allowed to think for themselves or be creative. People are known only by numbers. D-503 falls in love with the subversive I-330 who is planning to take over a new spaceship that D has helped design. D does not report her, but the authorities discover the plan from D’s diaries. He is arrested and subjected to the ‘Great Operation’ (like a lobotomy), after which he is able to watch I’s torture and execution without concern. This end result is similar to Winston Smith’s reconditioning in the dreaded Room 101 in Orwell’s book.

One author who had lived through the Stalinist era and revived science fiction in Russia in the 1950s was Ivan Yefremov. He bravely contrasted utopian and dystopian imagery in order to emphasise his dangerous viewpoint. In Tumannost’ Andromedy (1958; translated as Andromeda, 1959) he depicted an idyllic earth in the year 3000 with a society built on humanistic Marxist principles. It is the only convincing communist utopia. Yefremov then had second thoughts, and in the sequel, Chas Byka (‘The Hour of the Bull’, 1968; book, 1970), set two centuries later, he compared the ideal communist state with a dictatorship on another planet. Although he disguised the dictatorship by basing it on the Chinese model of communism, he was seen as criticising the Soviet Union, and the book, which had already been heavily censored, was banned. It was not republished in Russia until 1988.

City of Endless Night

The book that presaged all such totalitarian regimes was City of Endless Night (1920) by the American nutritionist and inventor Milo Hastings. Written towards the end of the First World War and first serialised under the title ‘Children of Kultur’ (1919), the novel looks a century hence with chilling prescience to a repressive, anti-Semitic and Nazi-like regime in a vast Berlin that has established itself as an impregnable dome-covered giant city on 60 levels, above and below ground, each level segregated by its class or rank. This city-state stands alone against the rest of the world which is now governed by a benign world state. In Berlin, eugenics is used to create a superior race with more men than women. Everything is tightly controlled and monitored, from each individual’s doctor and barber to their diet – all food is synthetic.

The influence of Nazism

Hitler’s rise to power and his growing dictatorship inspired several pre-war dystopias, such as Land Under England (1935) by Joseph O’Neill, with its totalitarian society living in vast subterranean caverns monitored by telepathic mind control, and Swastika Night (1937) by Katharine Burdekin (writing as Murray Constantine), where Germany and Japan rule a world in which women are kept in concentration camps and all Jews have been exterminated.

The prospect that Hitler’s forces might have won the Second World War and that Britain and most of Europe would be under Nazi control, introduces an alternative history form of dystopia, such as The Sound of His Horn (1952) by Sarban (John W Wall) or, more recently, C J Sansom’s Dominion (2012).

Probably the best known recent dystopian novel is The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) by Margaret Atwood, set a few decades hence when the United States government has been overthrown and a militaristic, racist and chauvinistic totalitarian regime has emerged. Women are segregated and have no authority. They are divided into several classes, one of which is handmaids, the equivalent of concubines. All African-Americans and Jews have been ‘removed’, believed exterminated. Abortions are illegal, and any deformed babies are eradicated.

Sociopaths, anarchy, disasters and cyberpunk

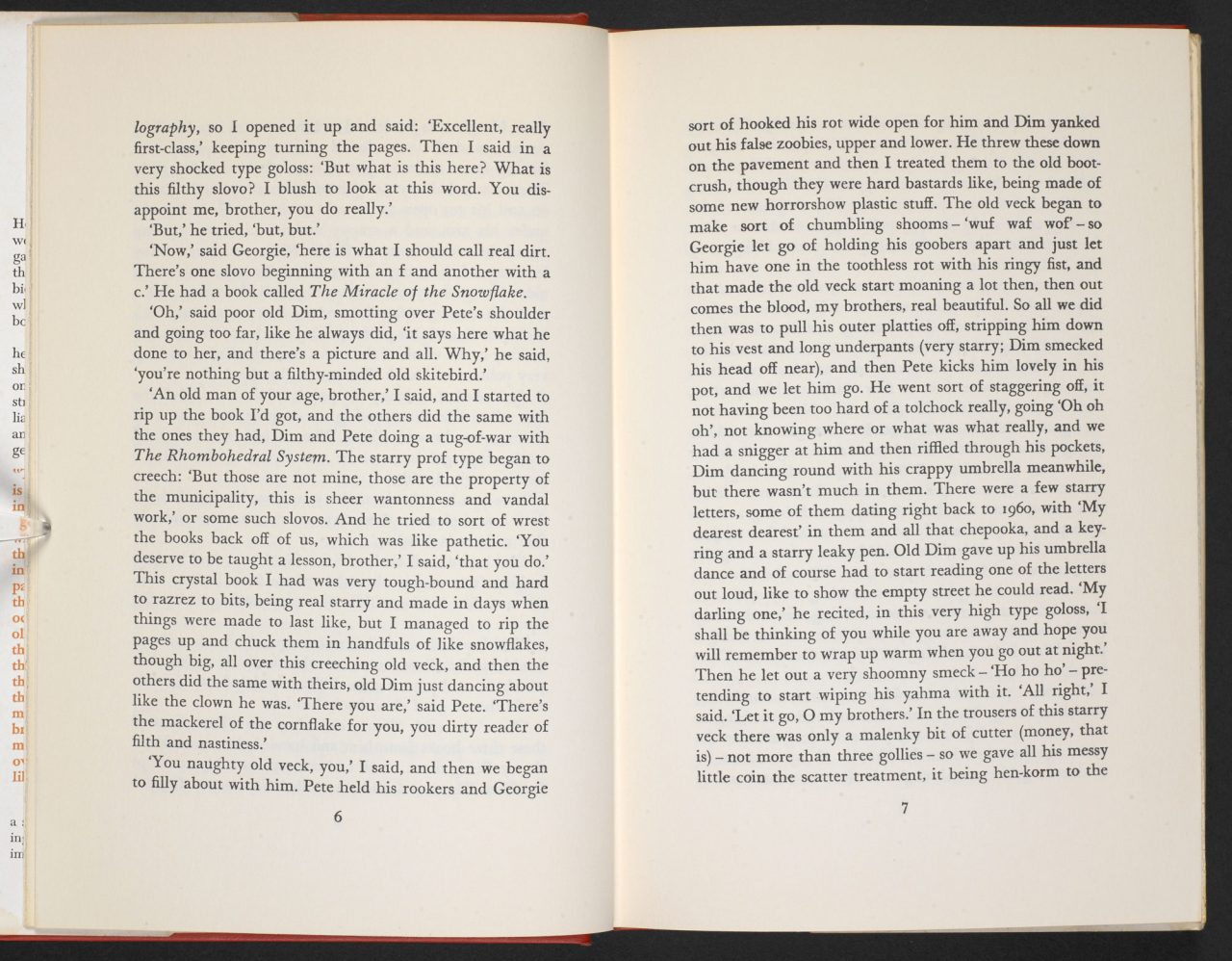

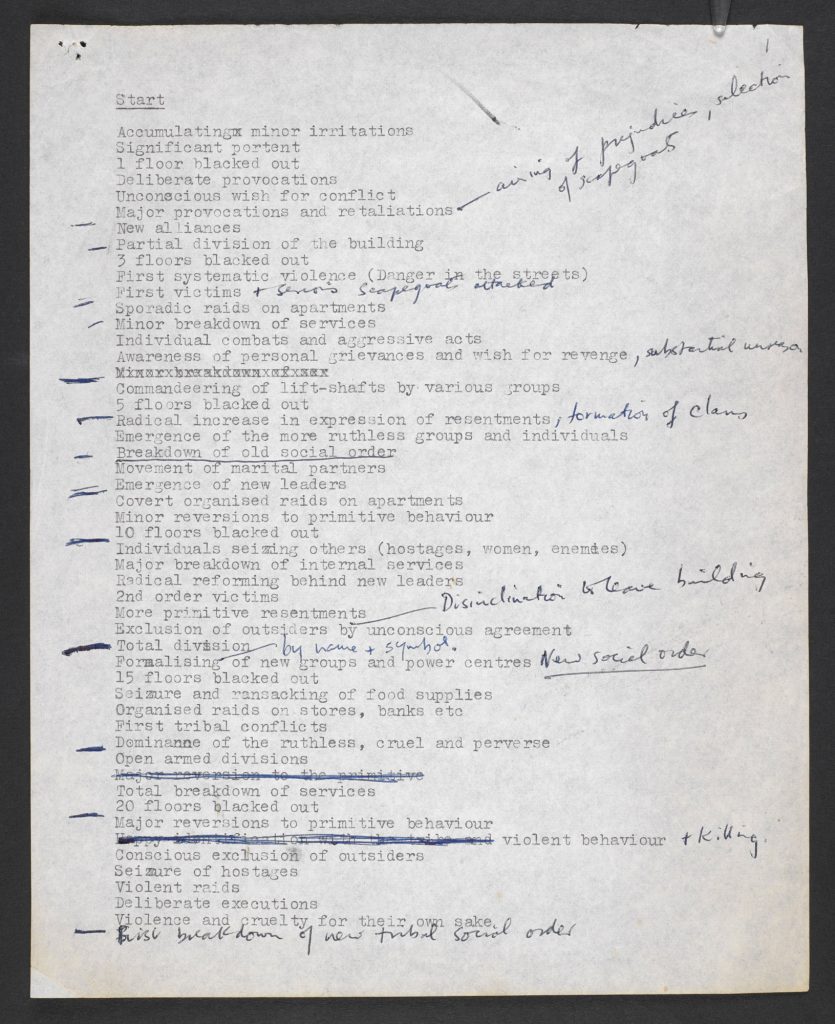

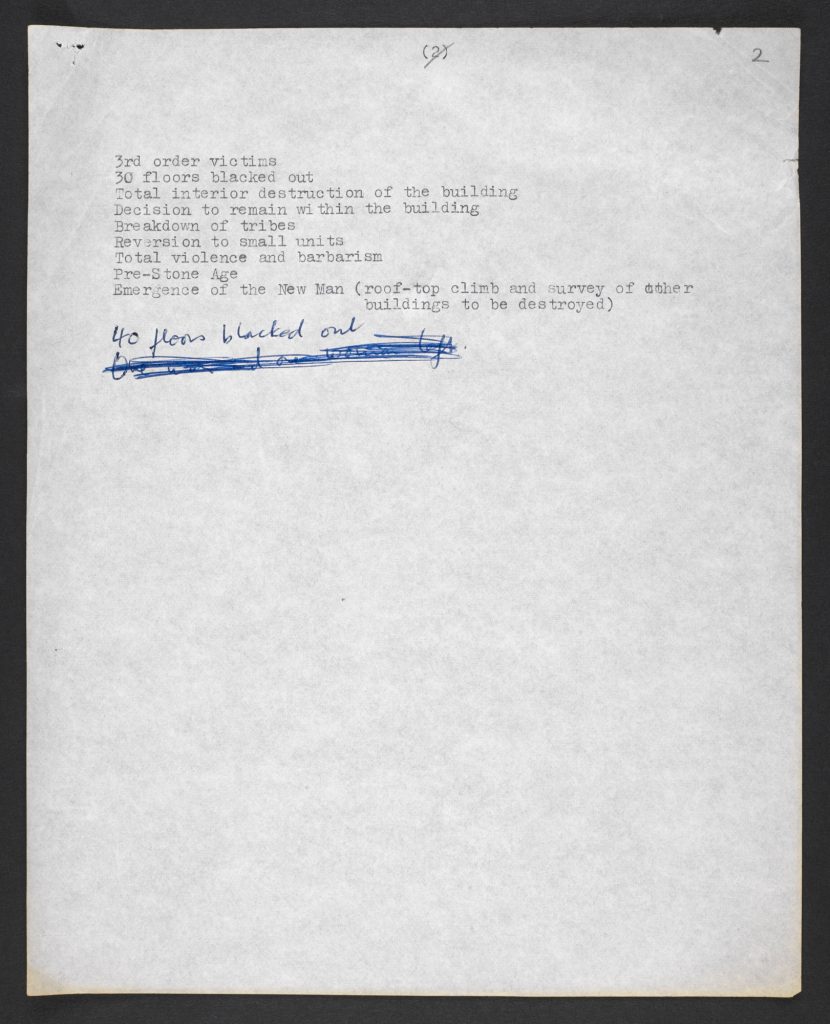

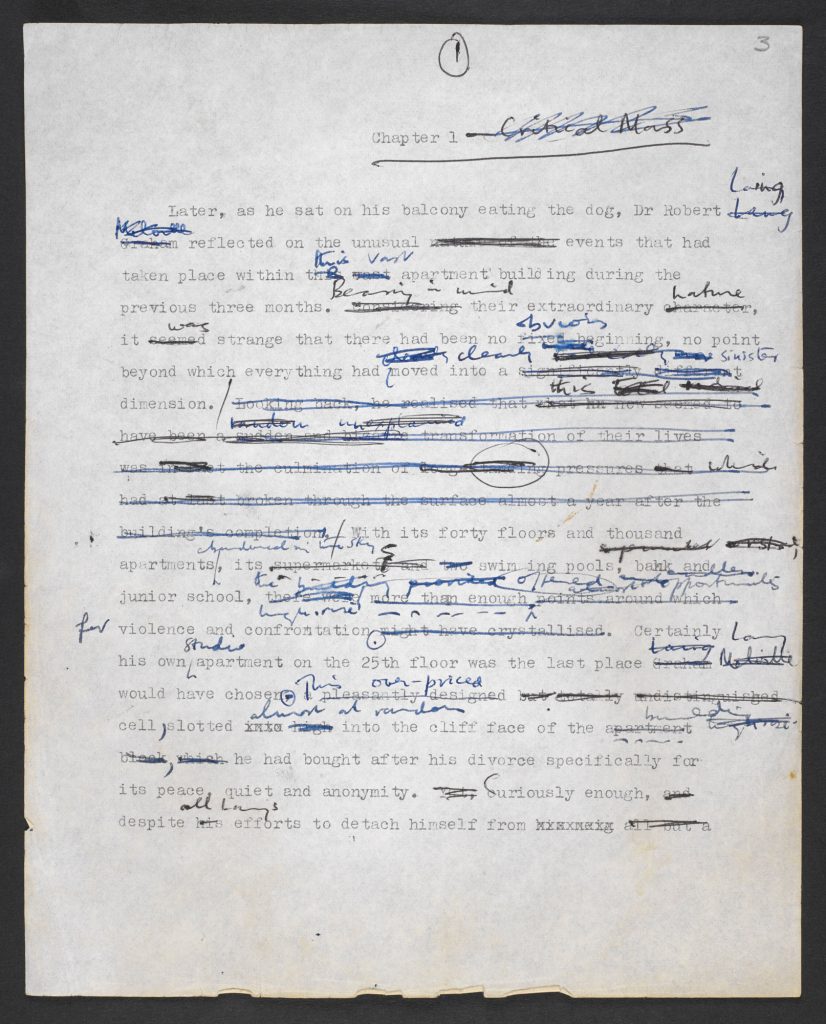

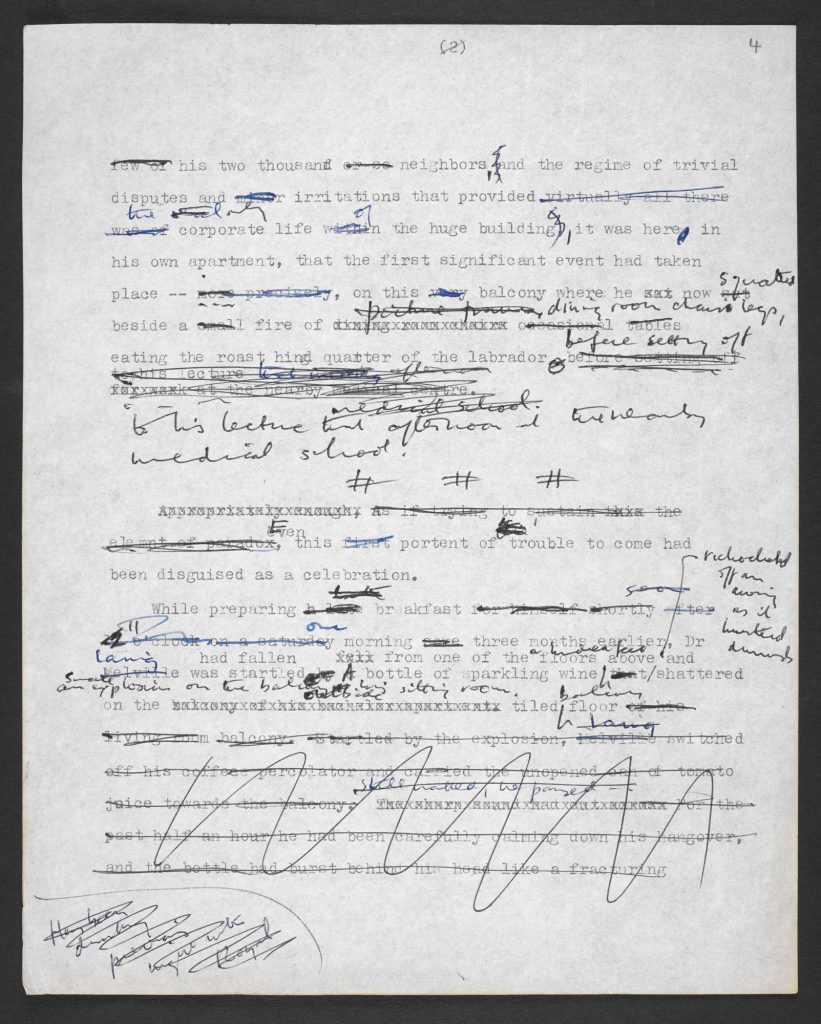

Dystopias do not have to be as extreme as Atwood’s novel. They are just as effective when their vision is only a short but decidedly uncomfortable shift from the here-and-now. Anthony Burgess achieved this with A Clockwork Orange (1971), which was written because of his concern over the rise of youth culture and juvenile delinquency. He envisaged a world where youths had become sociopathic and the government had to introduce a form of behavioural engineering and mind control in order to recondition them. The breakdown of society and a shift to anarchy is also the background to Michael Moorcock’s Black Corridor (1969), circumstances which provide the stimulus for the main character to escape from earth. The depressing scenes of social disorder had been drafted by Moorcock’s then wife, Hilary Bailey, who had also written of a Nazi-dominated Britain in her first short story ‘The Fall of Frenchy Steiner’ (1964). The breakdown of the social order is also evident in some of the later work of J G Ballard, especially High-Rise (1975), where the behaviour of the occupants of a high-rise luxury block of apartments soon degenerates to our basic primal urges when small problems in the building rapidly escalate into major ones. Ballard shows that the gap between utopia and dystopia is paper thin.

Dystopian futures can take many forms, arising from any number of causes or disasters, such as overpopulation, as depicted in Stand on Zanzibar (1968) by John Brunner, or radiation poisoning following a nuclear war as in Philip K Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968), memorably filmed as Blade Runner (1982). The film version depicted much of the iconography of cyberpunk, and some cyberpunk fiction itself draws on dystopian imagery. The underworld of Chiba City in William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984) will be seen as distinctly dystopian by many.

Authors have shown that it is easy to conjure dystopias out of any dark or disturbing possibility, demonstrating that there is more opportunity for the world to sink into a dystopian nightmare than evolve into a utopian dream.

撰稿人: Mike Ashley

Mike Ashley is a freelance writer and researcher with a special interest in the history of science fiction, crime fiction and fantastic literature. He has amassed a library of over 30,000 books and magazines including British popular fiction magazines of the years 1890-1940 which formed the basis for his book The Age of the Storytellers. He has completed four volumes in his planned five-volume Story of the Science-Fiction Magazines and his most recent publication, Adventures in the Strand, covers the relationship between Arthur Conan Doyle and The Strand Magazine.