From Tin-foil to Tango: Sound Recording and the Making of Popular Music

Dr Flora Willson explores the societal impacts of early music recording.

It doesn’t look like much: a rotating metal cylinder wrapped in tin-foil, a small, round mouthpiece and two needles, each attached to a diaphragm. But this unprepossessing contraption is now one of the most mythologised in the history of technology – as a machine that changed the world.

When the American inventor Thomas Edison filed a US patent for his latest design, late in December 1877, he called it the ‘phonograph’. Its main use, he suggested, would be for recording speech: from talking clocks and dictation to preserving the voices of dying family members. It was the last, macabre option – the sonic equivalent of new hi-tech chemical embalming techniques – that immediately caught the attention of contemporary technophiles. ‘Speech has become, as it were, immortal’, gushed the Scientific American, reporting on Edison’s invention.[1]

Tinfoil phonograph, replica from 1877

Given the fragility of those early tin-foil recordings, which were usually destroyed in the process of being removed from the cylinder on which they’d been made, the Scientific American’s announcement of the ‘immortality’ of recordings was premature. Yet more durable wax cylinders soon replaced Edison’s original tin-foil, making lengthy preservation a genuine possibility. And in 1887 Edison’s competitor Emile Berliner patented his ‘gramophone’, which recorded using a stylus onto flat, circular discs. Even more significantly, Edison’s initial, prosaic suggestions of how his invention might be used were also quickly overshadowed by larger and more profitable ambitions for the new technology.

Those ambitions were focussed on music. In 1896, the first issue of the short-lived magazine Phonoscope celebrated the fact that the great singers of the age could now ‘transmit to posterity all the excellencies they are so richly endowed with’. [2] Such transmission had vast commercial potential, as businessmen quickly realised on both sides of the Atlantic. Berliner himself founded the US Gramophone Company in 1894. Its UK and German counterparts were established in 1898, and the Victor Talking Machine Company was founded in Camden, New Jersey in 1901. The era of recorded music – and of the recording artist – was about to begin.

The birth of the recording artist

Some of the musicians persuaded to make recordings by the new companies were already household names in Europe, North America and beyond. The Australian soprano Nellie Melba, for instance, was both a critically acclaimed opera singer and a global celebrity – dishes including Peach Melba and Melba Toast were invented by famous chefs in her honour – by the time she made her first recordings in London in 1904. That first session included popular hits such as ‘Home Sweet Home’ and ‘Comin’ thro the Rye’ alongside operatic arias by Verdi, Mozart and Puccini. The mixture would have seemed natural for a singer as famed for her renditions of parlour songs as for her appearances on the world’s most prestigious operatic stages.

Song performed by Nellie Melba for Marconi’s experimental broadcast of 15th June 1920

Title: Song performed by Nellie Melba for Marconi’s experimental broadcast of 15th June 1920 Creator: Nellie Melba Held by: British Library Shelfmark: 9CL0033124 HMV DB 351 Copyright: Audio: Public Domain. Image: © Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

This studio recording of ‘Home, Sweet Home’ which Melba recorded in London eleven months later, is today the closest we can get to experiencing the sound of that first ever British radio performance by a professional musician. Surviving recordings from British radio’s first decade, the 1920s, are few, so it was astonishing when proof finally emerged of something long rumoured – that professional sound recordings had been made of Marconi’s legendary experimental broadcast of 15th June 1920 two and a half years before the launch of the BBC.

Marconi’s experimental broadcast

Britain’s first scheduled radio programmes had been transmitted three months earlier and generated considerable press interest. Soon after, newspaper magnate Lord Northcliffe offered to finance a programme designed to grab headlines around the world. The idea was simple – offer £1,000 to one of the world’s most famous singers to perform live in a broadcast from Marconi Company’s Chelmsford works of sufficient power to reach every home in Europe. The famous Australian operatic soprano Dame Nellie Melba was invited to take part.

Yet one of the most remarkable innovations of the event – a set of wax disc recordings made in a Paris laboratory – was largely forgotten for the next eighty years. Historian Tim Wander uncovered an article in a 1920 edition of the journal of the Société française radio-électrique about the recordings and an archival photograph of the recordings being made. No known copy of these recordings survive.

It was reported in the Mail that ‘Punctually at a quarter-past 7 the words of “Home, Sweet Home”, fitted to the familiar melody, swam into the receivers’ – and into the homes of astounded listeners all over Europe and the Middle East.

Who was Dame Nellie Melba?

Dame Nellie Melba (1861–1931), born Helen Porter Mitchell, became one of the most famous singers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Her participation in broadcasts and recordings made her one of the world’s earliest international recordings artists.

But the rise of commercial sound recording was also crucial to forming the divide we take for granted today, between ‘popular’ and ‘classical’ music. The cost of phonographs gradually dropped from the 1890s onwards, making them more affordable to an ever-growing market of consumers keen to buy recordings of a wide variety of musical genres. But the companies selling the machines and the records were quick to emphasise the refinement of their product. Adverts offered ‘The stage of the world in your home’ and promised ‘The highest class talking machine’. No wonder the Victor Talking Machine Company cannily created a separate, more expensive Red Seal line of opera recordings – a move that profitably boosted the perceived prestige of the entire brand.

Sound recording’s growing commercial success inevitably posed a threat to existing musical ecosystems. American bandleader John Philip Sousa, for example, had relied financially on a feedback loop between sales of his sheet music and of tickets to his concerts; those who bought one would soon end up buying the other. Sound recording, he feared, would lead to the extinction of the amateur musician and undermine attendance at live performances. After all, recordings such as the Queen’s Hall Orchestra’s 1902 concert cylinder of Weber’s Invitation to the Waltz were sold in a format that made them usable in public concert halls, as a new form of public entertainment.

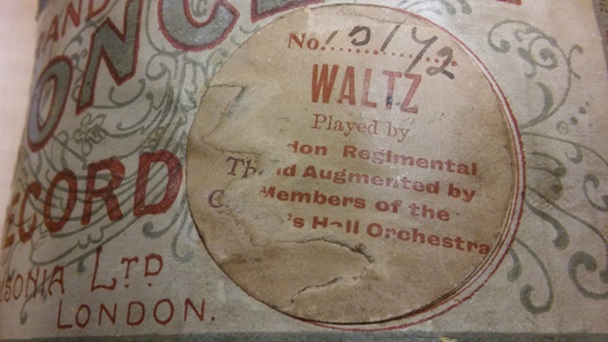

Invitation to the Waltz

Title: First concert recorded by the Queen’s Hall Orchestra Creator: Queen’s Hall Orchestra, London Regimental Band Held by: British Library Shelfmark: 1CYL0003804 Copyright: Audio: Public Domain; Image: Public Domain

This recording of Carl Maria von Weber’s Invitation to the Waltz, from 1902, is probably the first concert recorded by the Queen’s Hall Orchestra. They perform alongside the London Regimental Band.

Who were the Queen’s Hall Orchestra?

The Queen’s Hall was opened in London in 1893, and within a few years it became the home of promenade concerts (which became informally known as the ‘Proms’) led by performances from its own orchestra. The Queen’s Hall Orchestra was conducted by Henry Wood, who often played the piano in performances.

The Proms’ popularity was interrupted when disaster struck during the Second World War, as the Hall was burnt down as a result of an air raid in 1941.[1] Consequently, the promenade concerts, now the BBC Proms, moved to the Royal Albert Hall.

Were people able to listen to concerts in their own homes?

This recording of Invitation to the Waltz was sold on concert cylinders, which were developed to produce a louder sound. This allowed them to be played in homes, public concert halls and outdoor spaces. In 1902, a total of 20 recordings were made by the London Regimental Band and members of the Queen’s Hall Orchestra.[2]

However, the cylinders could only be played by Grand Concert Phonographs, which were much larger than the standard phonograph. As with the size of these machines, there also came a substantial cost with some retailing between 16 and 40 pounds in 1902.

The concert cylinder was donated to the Library by Jolyon Hudson.

[1] Parkin, P H, ‘Acoustic of Concert and Multi-Purpose Halls’, in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences, 272:1229 (1972), pp. 621–25, <https://www.jstor.org/stable/74099

[2] As advertised in the Phonograph and Talking Machine Exchange, 1902.

In his 1906 article ‘The Menace of Mechanical Music’, Sousa vigorously decried the phonograph:

Sweeping across the country with the speed of a transient fashion in slang or Panama hats, political war cries or popular novels, comes now the mechanical device to sing for us a song or play for us a piano, in substitute for human skill, intelligence, and soul. [3]

By the 1920s, though, even Sousa was extolling the advantages of sound recording, which he credited with creating ‘a lively sense of musical appreciation’ and familiarity with what he called ‘good music’ in communities far from an opera house or orchestra.

Remaking musical genres

For better and worse, the demands of recording itself had an audible impact on certain musical genres. The Original Dixieland Jazz Band were playing regularly at a New York restaurant when they were invited to audition by two competing record labels in 1917. Columbia heard the New Orleans quintet first but were beaten to the recording studio by Victor. The resulting double-sided record – ‘Livery Stable Blues’ and the ‘Dixieland Jass Band One-Step’ – is generally considered the world’s first jazz record.

But the rise of commercial sound recording was also crucial to forming the divide we take for granted today, between ‘popular’ and ‘classical’ music. The cost of phonographs gradually dropped from the 1890s onwards, making them more affordable to an ever-growing market of consumers keen to buy recordings of a wide variety of musical genres. But the companies selling the machines and the records were quick to emphasise the refinement of their product. Adverts offered ‘The stage of the world in your home’ and promised ‘The highest class talking machine’. No wonder the Victor Talking Machine Company cannily created a separate, more expensive Red Seal line of opera recordings – a move that profitably boosted the perceived prestige of the entire brand.

Sound recording’s growing commercial success inevitably posed a threat to existing musical ecosystems. American bandleader John Philip Sousa, for example, had relied financially on a feedback loop between sales of his sheet music and of tickets to his concerts; those who bought one would soon end up buying the other. Sound recording, he feared, would lead to the extinction of the amateur musician and undermine attendance at live performances. After all, recordings such as the Queen’s Hall Orchestra’s 1902 concert cylinder of Weber’s Invitation to the Waltz were sold in a format that made them usable in public concert halls, as a new form of public entertainment.

脚注

- Edward H. Johnson, ‘A Wonderful Invention – Speech Capable of Indefinite Repetition from Automatic Records’, Scientific American, 37/20 (17 November 1877), p. 304.

- ‘Voices of the Dead’, Phonoscope 1/1 (15 November 1896), p. 1; quoted in Jonathan Sterne, The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003), p. 308.

- John Philip Sousa, ‘The Menace of Mechanical Music’, Appleton’s Magazine, 8 (September 1906), p. 278; quoted in Patrick Warfield, ‘John Philip Sousa and “The Menace of Mechanical Music”’, Journal of the Society for American Music, 3/4 (2009), p. 431.

Banner image © Laura White

撰稿人: Flora Willson

Dr Flora Willson is a Lecturer in Music at King’s College London, where her teaching and research focuses on music, technology and urban culture in the long nineteenth century. She is currently writing a book about operatic culture and urban infrastructures in 1890s London, Paris and New York and also writes about music for The Guardian.