Jack the Ripper

The unidentified killer known as Jack the Ripper murdered a series of women in the Whitechapel area of London during 1888. Judith Flanders explores how the excitement and fear surrounding the mysterious murderer made its way into late-Victorian literature.

Contemplating the murderer William Palmer, Charles Dickens saw a face conveying ‘nothing but cruelty, covetousness, calculation … and low wickedness’. He liked, he said, a murderer who looked like a murderer.

A murderer who looks just like everyone else

That was in life; in his fiction the novelist had long been exploring the notion of a murderer who looked, frighteningly, just like everyone else. In Our Mutual Friend, Bradley Headstone is a respectable teacher, but he nevertheless plans a murder. In The Mystery of Edwin Drood, John Jasper is a model citizen, a choirmaster who is (most likely) also a murderer. (We don’t know because Dickens died before he finished the novel.)

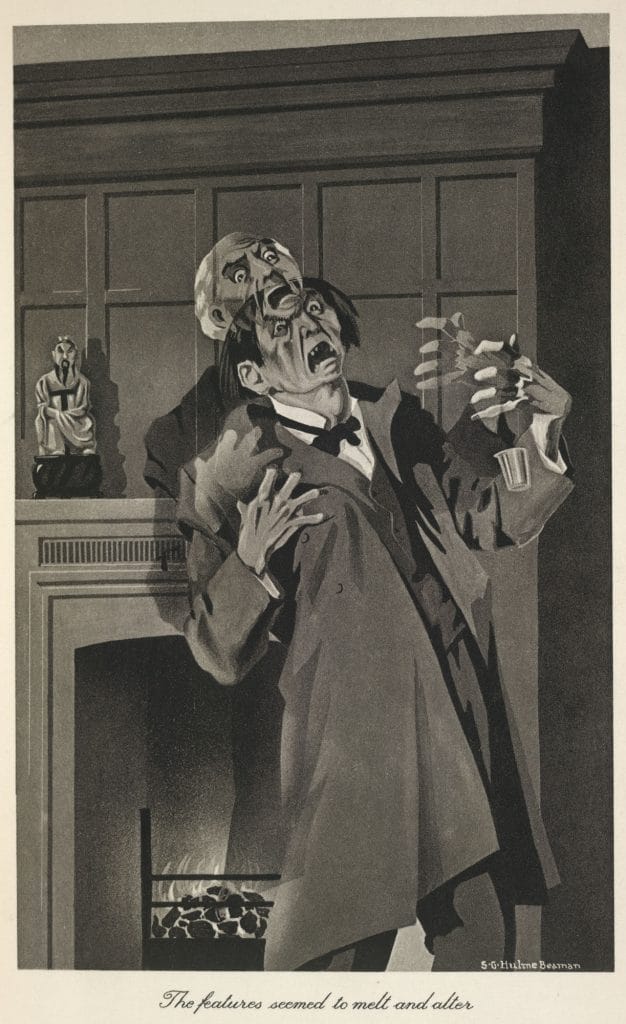

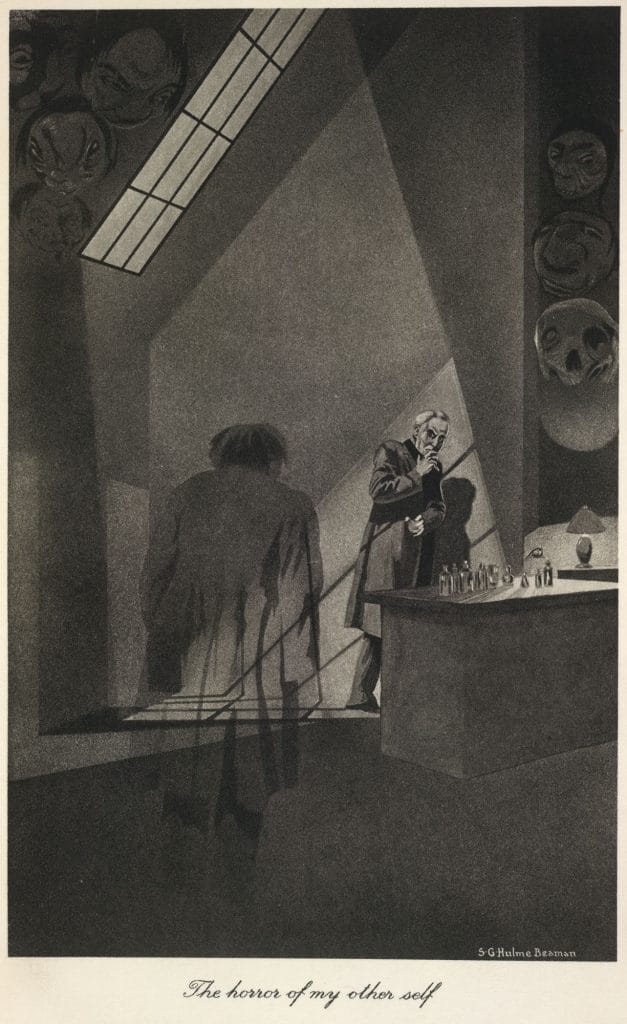

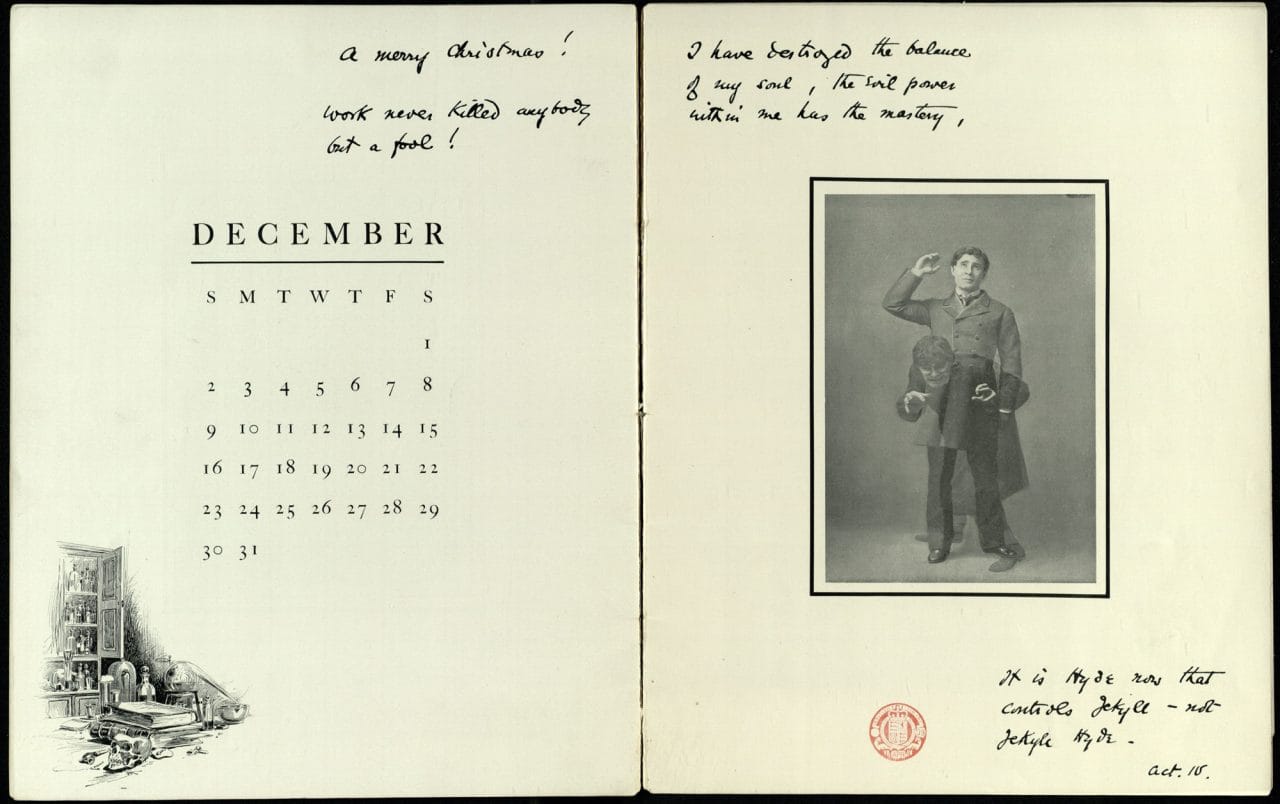

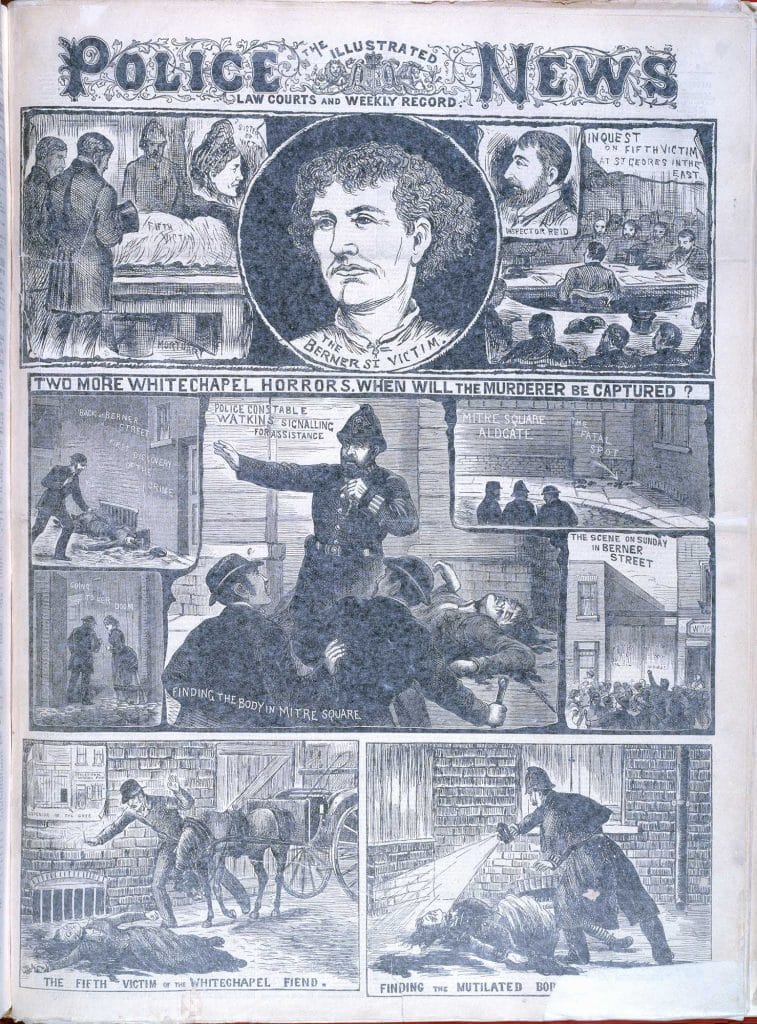

In January 1886, the Scottish writer Robert Louis Stevenson created a hugely influential picture of this terrifying doubleness, in The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. This novella, about a doctor who, on taking certain drugs, transformed himself into a thug-like murderer, sold 40,000 copies in the first six months. And soon thousands who had not read the book saw play adaptations.

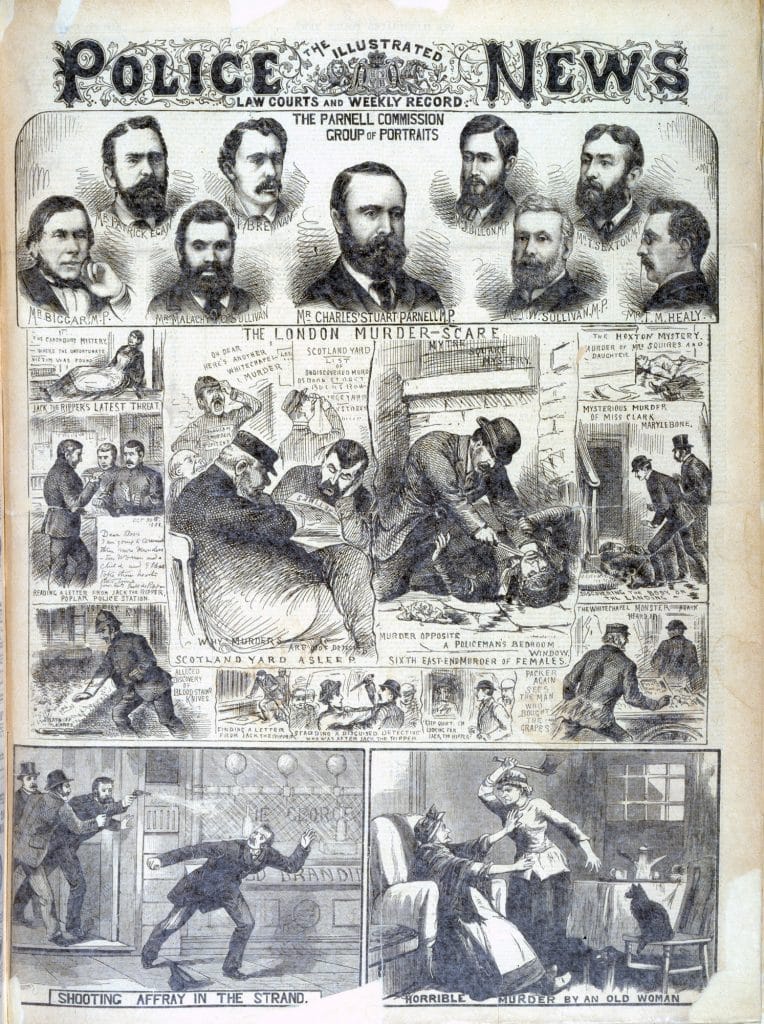

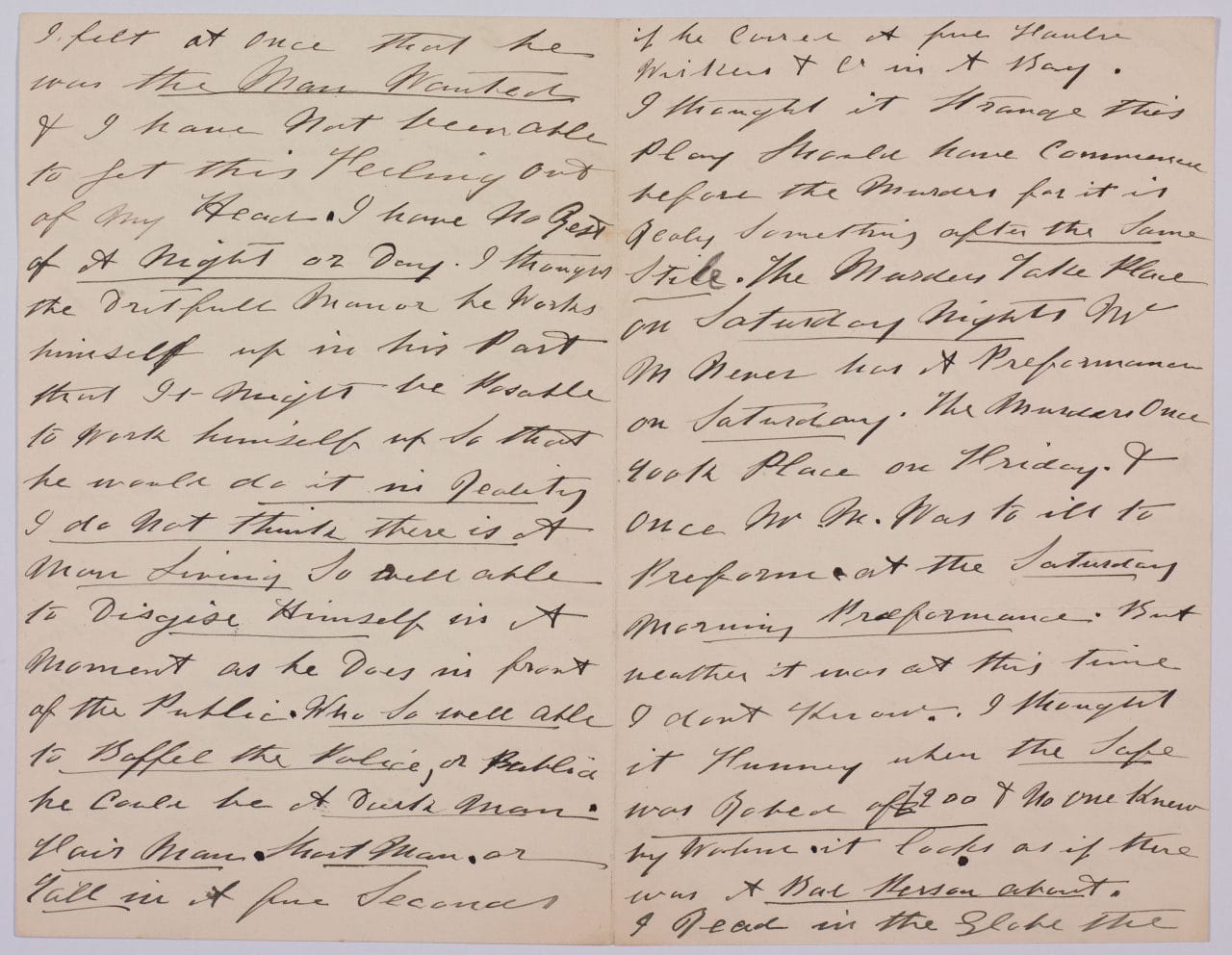

In August 1888, the most famous adaptation opened, with Richard Mansfield in the double-part. He transformed himself in front of the fascinated audience’s eyes, by changing posture, gait (and probably lighting). When, three weeks later, a prostitute was found murdered in Whitechapel – the start of the series of murders known as the Jack the Ripper killings – many people connected Stevenson’s outwardly respectable Dr Jekyll and the murderous Mr Hyde with the invisible East End killer. The newspapers routinely referred to the murderer as Mr Hyde.

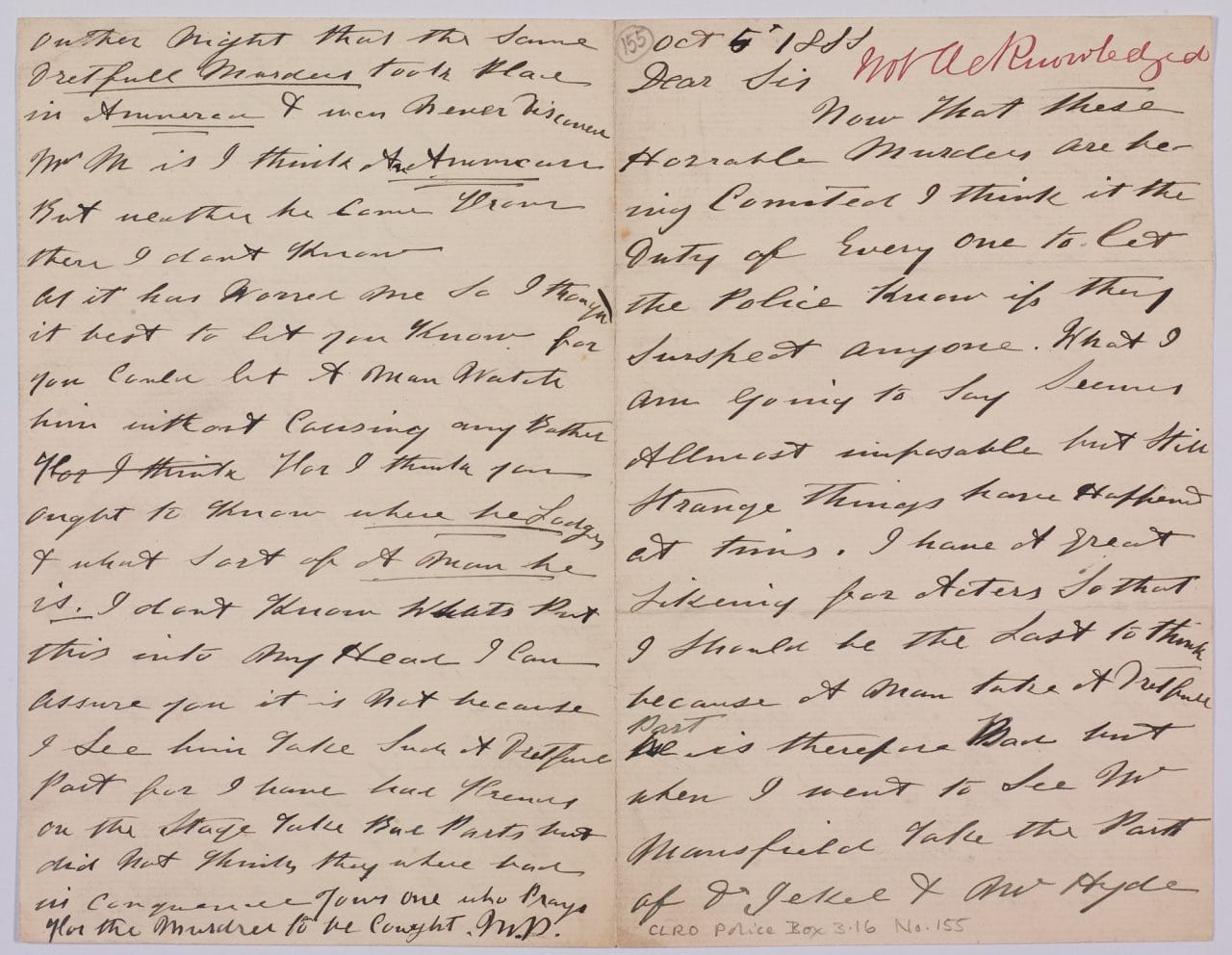

One member of the public even sent the police a letter denouncing Mansfield: ‘I should be the Last to think because A man take A dretfull Part he is therefore Bad but when I went to See Mr Mansfield Take the Part of Dr Jekel and Mr Hyde I felt at once that he was the Man Wanted … I do not think there is A man Living So well able to disgise Himself in A moment…’

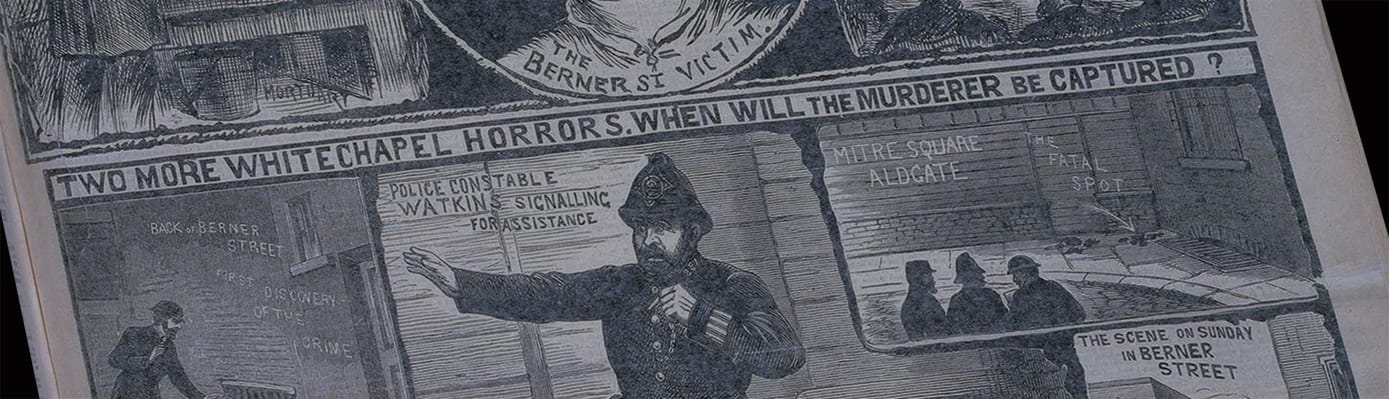

The unknown murderer

It is not known if Scotland Yard ever followed up this fanciful suggestion, but the murders laid at the door of the unknown killer have occupied the public imagination ever since. The crimes of the unknown person dubbed ‘Jack the Ripper’ have probably had more written about them than any since Cain killed Abel. The great horror – and the great fascination – of this series of murders is that they are entirely unknowable. The date they began, or ended, is open to question; the number, and sometimes even the names, of the victims is disputed. There was no arrest, no trial, no verdict to draw a line under the case, only a shadowy figure and a nickname that came from a letter that was almost certainly written by a hoaxer. Five women at least, and possibly more, were murdered and mutilated in the East End of London. Whether it was by a single person, as is popularly supposed, or by more, is unknown. Many at the time and since have suggested, following Stevenson’s lead, that the murderer was an outwardly ‘respectable’ (read, middle- or upper-class) man.

Outward respectability and inner corruption

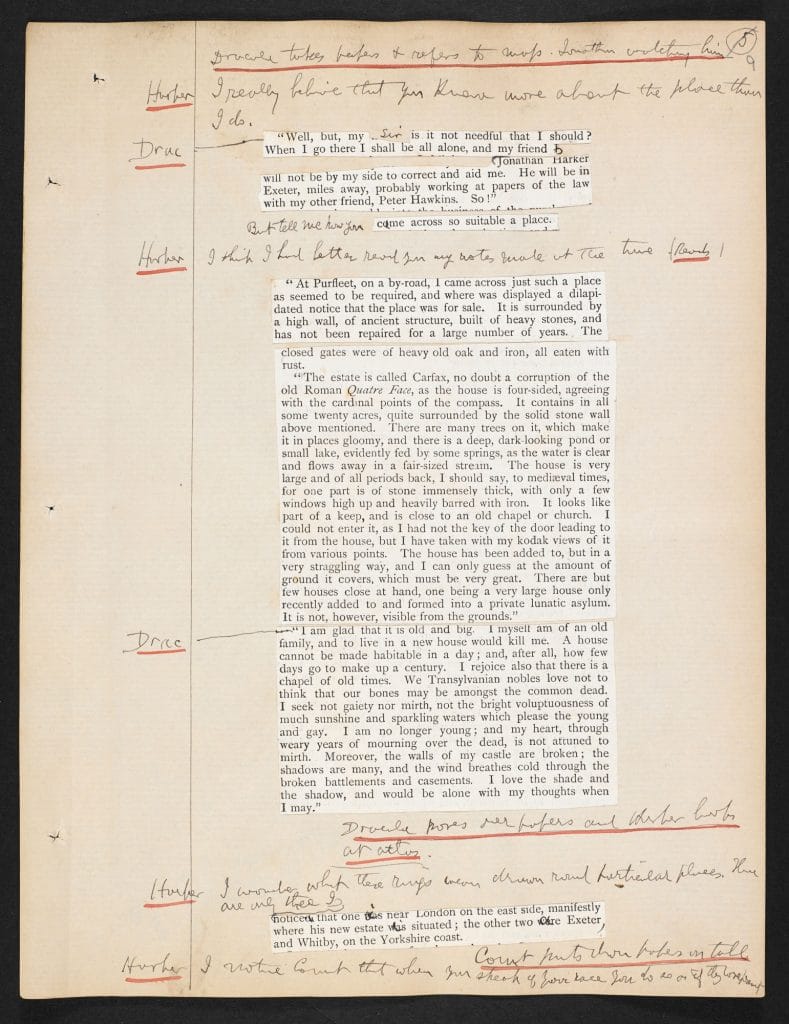

And so, as the events in real life unfolded, the play of Jekyll and Hyde was closed, for reasons of taste. Yet the idea of outward respectability and inner corruption remained in the air. One East End newspaper, reporting the murders, wrote that ‘the mind turns … to some theory of occult force, and the myths of the Dark Ages’, and a year later, one part-time writer began to concentrate on exactly that: Bram Stoker wrote his first notes for what would become Dracula. Many parallels can be found: five women were murdered in Whitechapel, while Dracula has five ‘brides’, whom he attacks and mutilates; the doctor carries a black bag, while in Whitechapel a man was arrested for nothing more; van Helsing and his friends form what Stoker in his notes called a ‘vigilance committee’, while in Whitechapel, the Mile End Vigilance Committee patrolled the streets. The East End was home to thousands of Jewish emigrants, and much of the reporting had a heavily anti-Semitic tone to it. The crimes, said the East London Observer, were so vile they ‘must have been done by a Jew’. Stoker transformed this prejudice, this fear of the stranger, particularly the Eastern European stranger, into art.

He was not alone. Oscar Wilde, too, used the idea of doubling, and made it more terrifying by focusing not on the stranger, but on an insider, the frank beautiful, open Dorian Gray in The Picture of Dorian Gray, published only three months after Stoker made his first notes. With his picture of Gray, Wilde drew on the uncertainties of Whitechapel, the idea that no one was what they seemed, that any respectable person might harbour an evil secret. Gray’s biography allows for a Ripper-like private life: there are ‘mysterious and prolonged absences’, he has a ‘sordid room of the little ill-famed tavern near the Docks’ – that is, in the East End, not far from where the murders took place, where he stays ‘under an assumed name, and in disguise’, while ‘stories that you have been seen creeping at dawn out of dreadful houses and slinking in disguise into the foulest dens in London’ circulate (ch. 11; ch. 12). Ultimately Gray commits an unspeakable crime, becoming, in literature, no different from the Ripper on the real streets.

Stevenson predated the Ripper killings; Wilde and Stoker wrote in an atmosphere where both Stevenson’s work, and the real murders, were established fact. But the notions that they discussed – otherness, alienation, violence and despair, became a staple of the modernism they anticipated.

The text in the article is © Judith Flanders. It may not be reproduced without permission.

撰稿人: Judith Flanders

Judith Flanders is a historian and author who focusses on the Victorian period. Her most recent book The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens’ London was published in 2012.