Life of Oscar Wilde

From Wilde’s early success to the notorious trial and life in exile, Andrew Dickson explores the life and works of Oscar Wilde and his legacy today.

Introduction

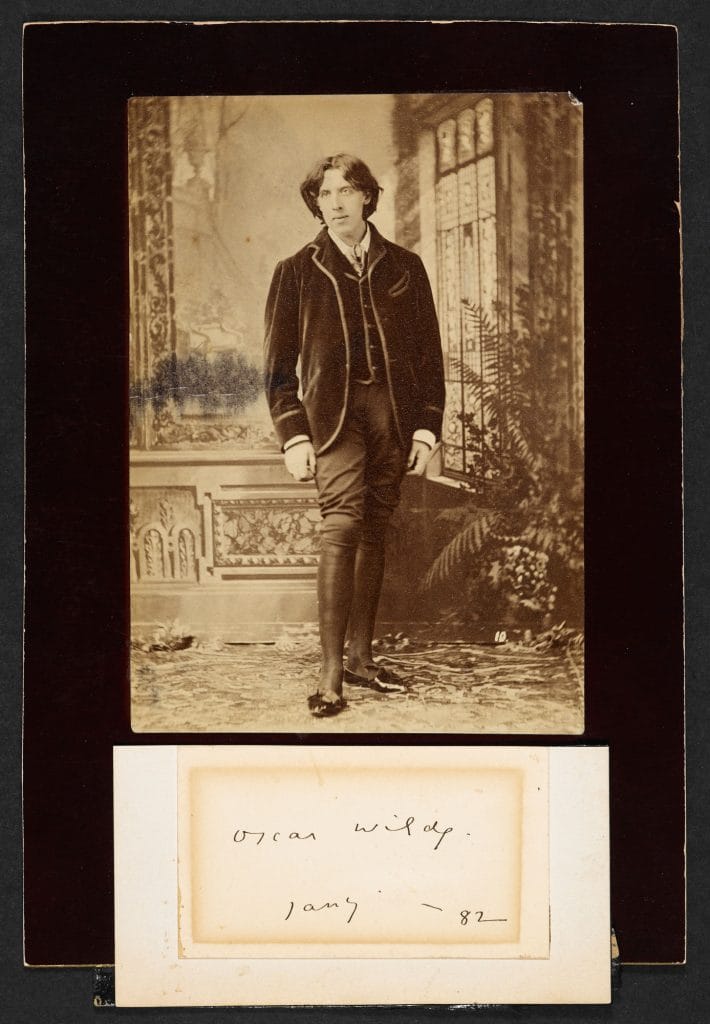

Oscar Wilde was many things. He tried on identities almost like costumes – by turns a celebrity playwright and poet, an expatriate Irishman adrift in England, and a well-dressed aesthete and dandy, whose beautifully turned but provocative witticisms made him the toast of late-Victorian London. Last, and certainly not least, Wilde was a gay man in the UK during a period when it was both illegal and dangerous to be so – something that has made him an icon for campaigners ever since. His relationship with another man ended in a humiliating court case and prison sentence that ruined him physically, emotionally and financially. Broken by the experience, he died the age of just 46. Even in his own lifetime, the Oscar Wilde myth was always in danger of eclipsing the man, as the countless books, plays and film devoted to him demonstrate – the latest movie, Rupert Everett’s The Happy Prince, was released earlier this year.

But there are more intriguing sides to Wilde, too, particularly in his writing. He was prolific in an unusual variety of fields – achieving success and fame as a playwright, a poet, a novelist, an essayist and lecturer as well as an author of children’s stories. Yet despite being one of the most brilliant comic writers in the history of world theatre, throughout his life Wilde battled to be taken seriously as an artist, a battle which he feared he had never truly won. ‘I put all my genius into my life, I put only my talent into my books’, he once remarked. The observation is accurate, and also strangely moving.

Wilde’s early years

Born into a cultivated and well-connected family in Dublin, Oscar Wilde had a charmed childhood, outwardly at least. His father was one of Ireland’s leading medical surgeons, and his mother was a poet and expert on Irish folklore. After being educated at home, then sent away to boarding school in Enniskillen in what is now Northern Ireland, in 1871 the teenage Oscar won a scholarship to Trinity College, Dublin, one of Ireland’s most prestigious universities. A few years earlier, the family had been shocked by the death of his young sister Isola; Oscar was especially grief-stricken. Isola became the subject of one of his earliest published works, the 1881 poem ‘Requiescat’ (the Latin title for a prayer for the dead). Wilde carried a lock of her hair around with him for the rest of his life.

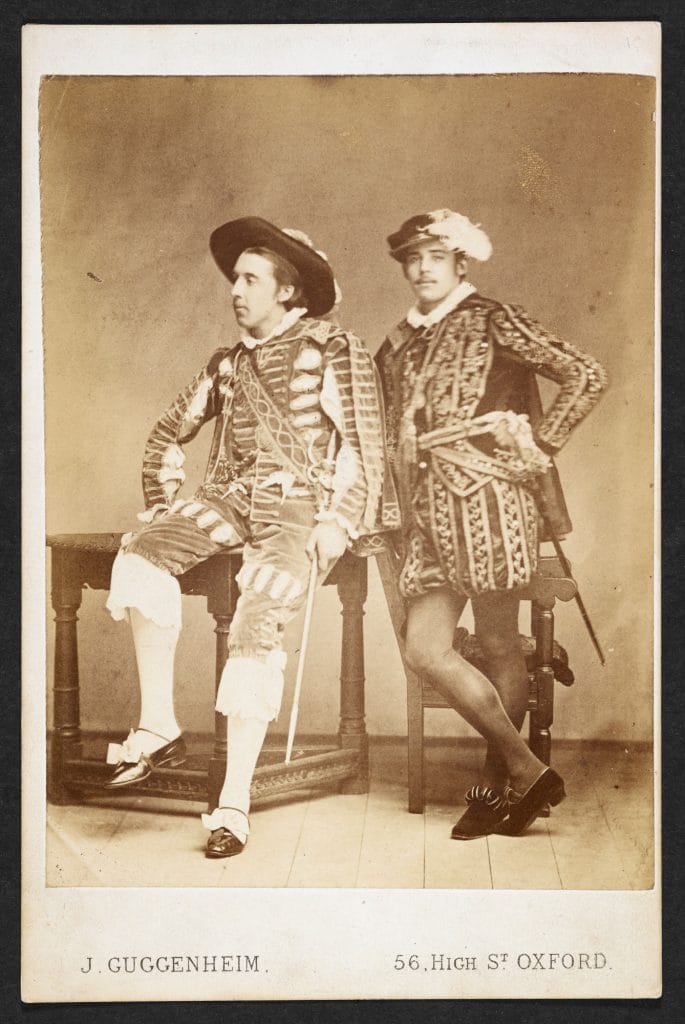

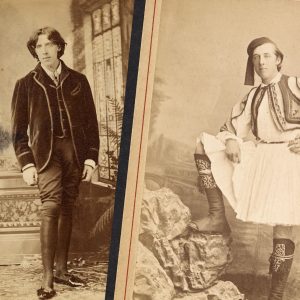

Nonetheless Wilde excelled academically, and in 1874 won a scholarship to Oxford University to study Classics. His years in Oxford were as much a social as an intellectual education. Wilde fell into the circle of the art critics and theorists Walter Pater and John Ruskin, both titanic figures in the cultural world of the time. And despite cultivating a reputation for laziness and luxurious living – the collection of Chinese porcelain he kept in his college rooms became famous – he graduated with a double first-class degree, the highest possible mark, and won a poetry prize. He moved to London soon afterwards and embarked on a literary career.

Wilde soon became a fixture of the London arts and social scene, famous for being famous. His reputation was enhanced by his wit, skill as a raconteur and flamboyant dress sense (he was known for his colourful bow ties and extravagant hats) . He also made a name for himself as a leading light of the so-called ‘aesthetic’ movement, with its famous rallying cry of ‘art for art’s sake’. This theory called for culture to be celebrated for the pure pleasure it induces in the beholder rather than for the moral or political message it conveys. Such was Wilde’s fame in polite society that in 1881 Gilbert and Sullivan, whose comic operettas were hugely popular at the time, lampooned him in their new work Patience. Wilde was, predictably, delighted.

The following year, he cannily made a deal with Patience’s producer to travel to the United States and give a series of lectures on artistic topics. Legend has it that, being asked at the Custom House in New York whether he had anything to declare, Wilde replied, ‘I have nothing to declare except my genius!’

Breakthrough and success

Despite his early successes, Wilde yearned to become a serious artist – most especially a playwright. The dream stubbornly eluded him. His first play, a tragedy called Vera (1881), failed when it was produced in New York. His second, a dour historical work in Shakespearian verse called The Duchess of Padua, was rejected by the actress who commissioned it. His personal life seems to have been happier. In 1884, he married Constance Lloyd, the daughter of a well-known Irish barrister; together, the couple had two boys, Cyril and Vyvyan. It looked like an ideal family, at least to observers.

Although the family was constantly short of money, Wilde loved being a father, and several bedtime stories he originally told to his sons, including ‘The Selfish Giant’ and ‘The Nightingale and the Rose’, were published in his children’s collection The Happy Prince and Other Stories in 1888. In their mythic simplicity, and delicate balance between joy and sadness, they are among the best things Wilde ever wrote. He also achieved success with published versions of his essays.

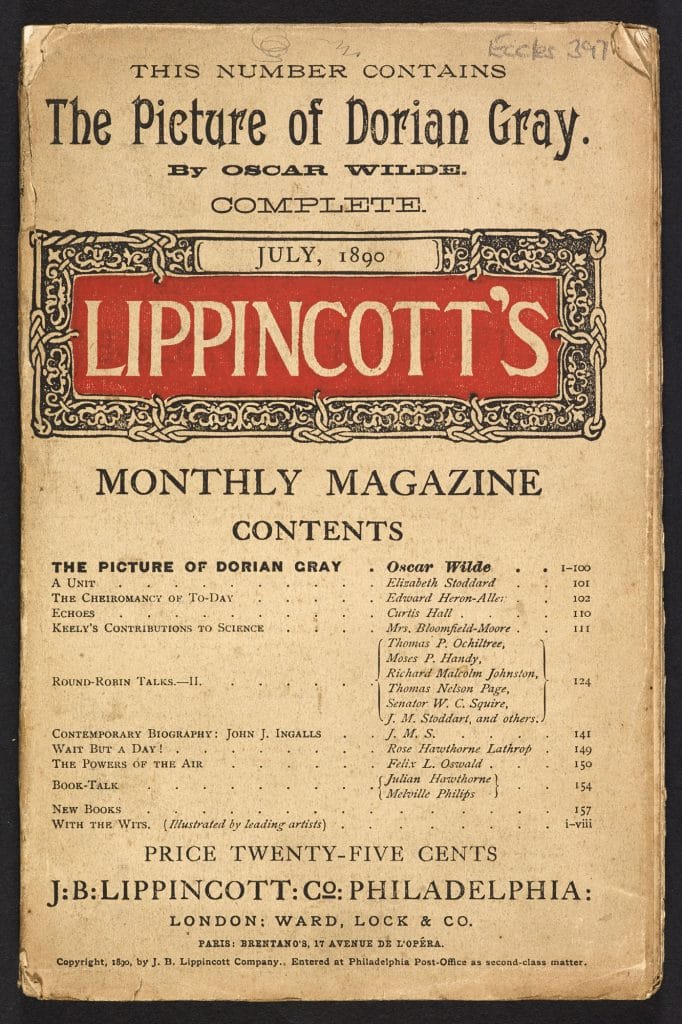

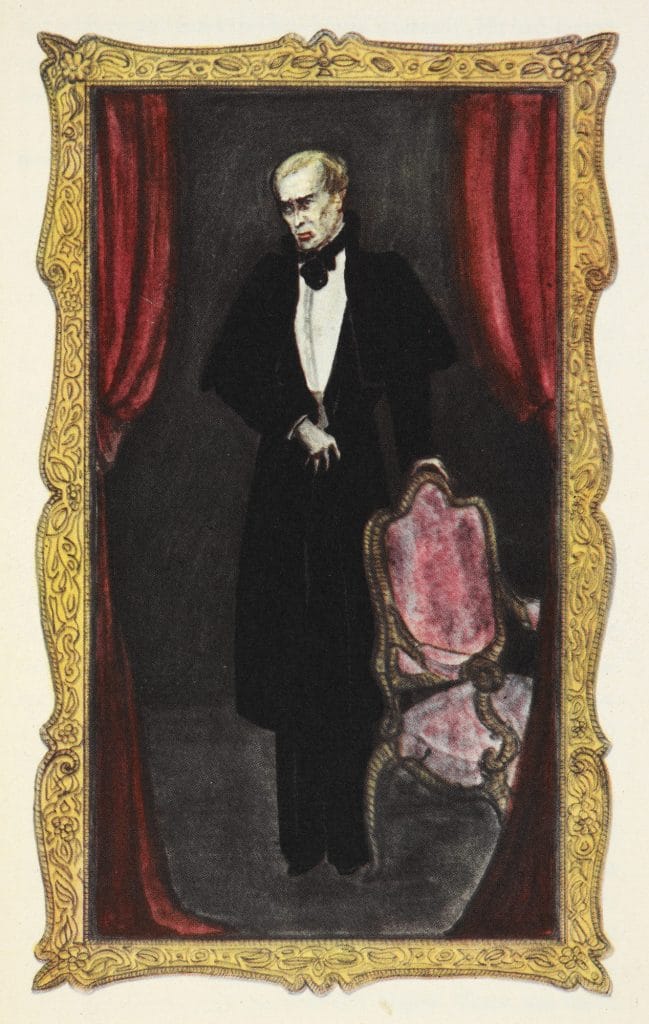

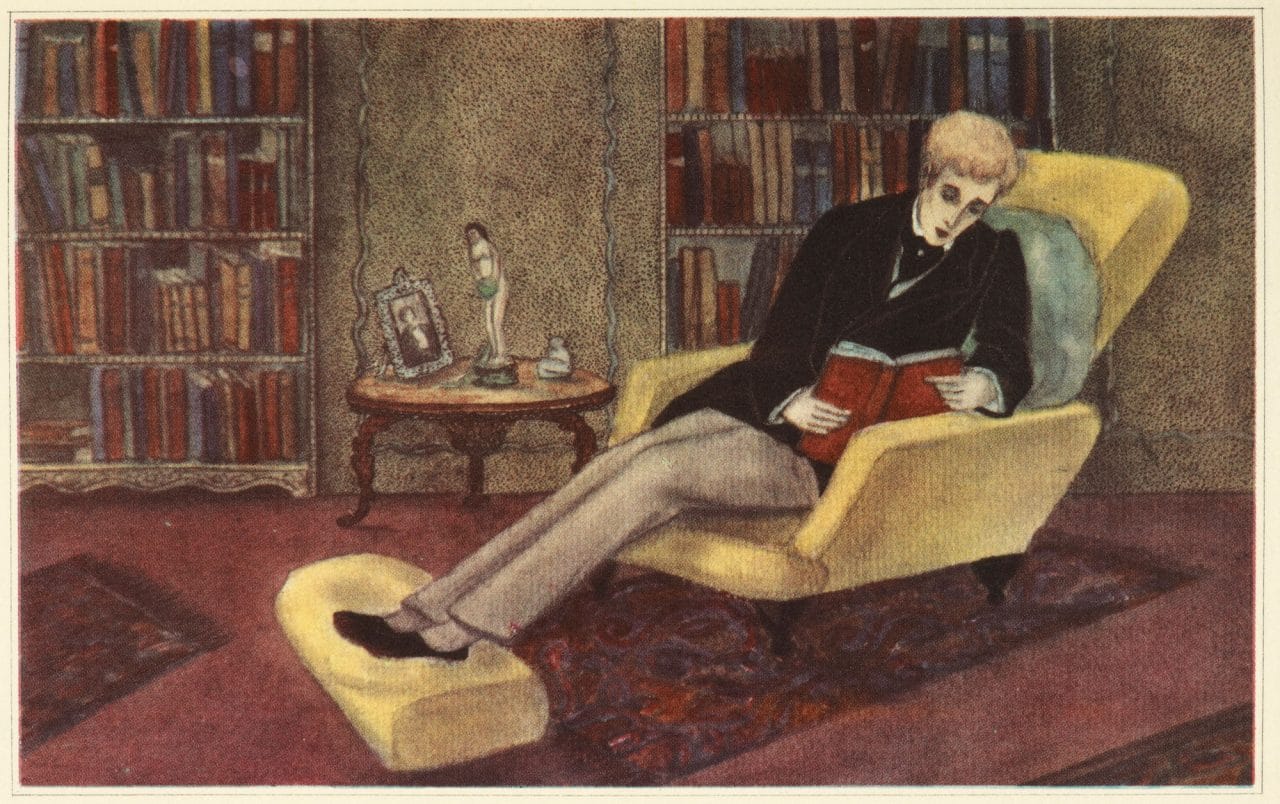

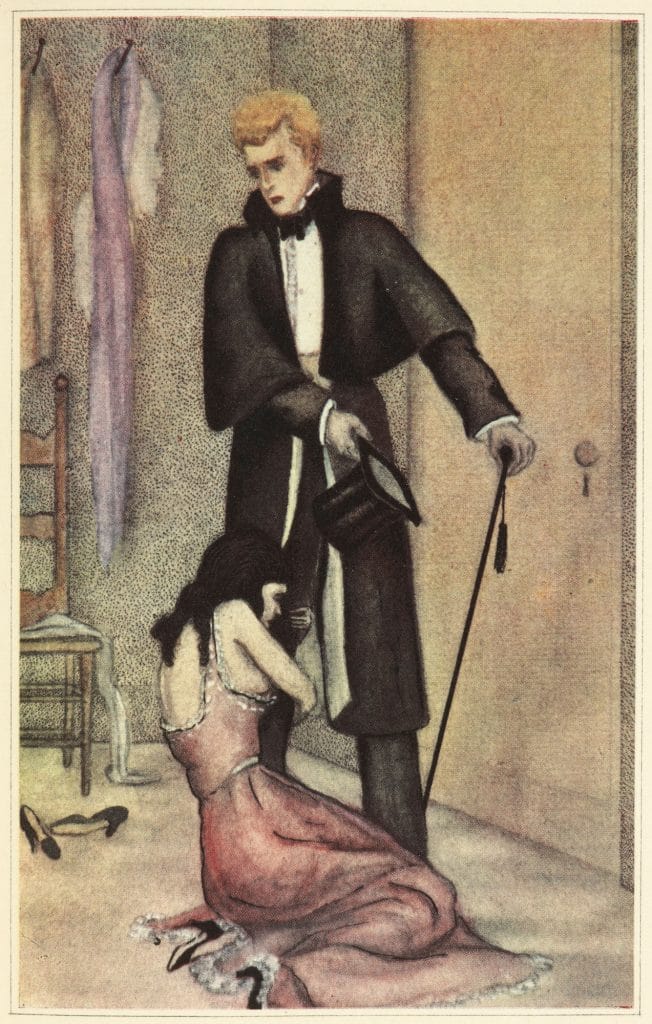

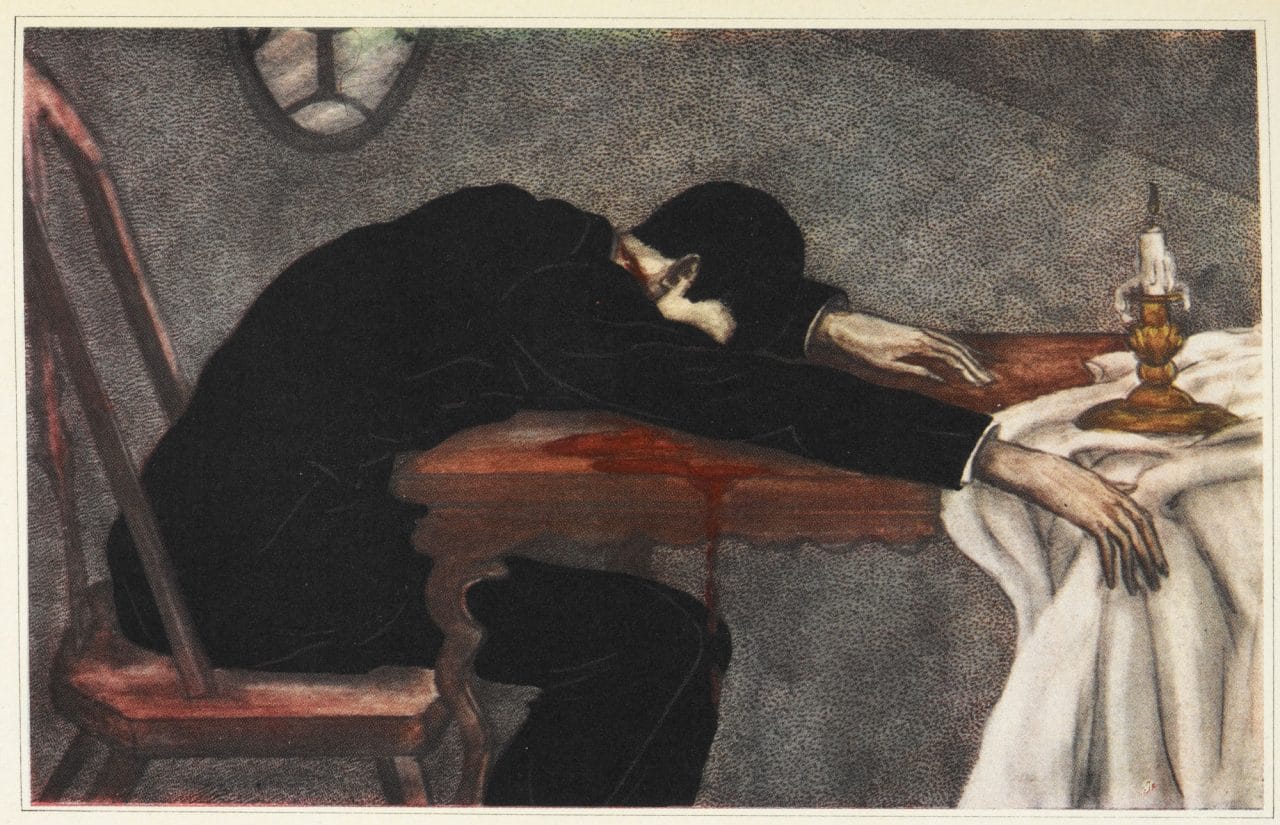

Success of a more scandalous kind followed the publication of Wilde’s novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray, which first appeared in a magazine before being printed in book form in 1891. Dorian Gray tells the fantastical story of a beautiful young man who buys eternal youth and pays for it with his soul. Desperate not to lose his youthful beauty, Dorian makes a wish that a painted portrait of him will grow old, while he himself stays young – he finds that this is exactly what happens. Despite embarking on a life of non-stop debauchery and hedonism, exploring every vice available to him and even resorting to murder, Dorian looks as beautiful as ever, while the portrait becomes hideously deformed.

Nodding both to the ghoulish traditions of the Gothic novel and also myths such as that of Faust, who made a pact with the devil to gain eternal knowledge, Dorian Gray shocked many readers. The critics rounded on Wilde, accusing him of immorality and describing the novel as ‘effeminate’ and ‘unmanly’. From a contemporary perspective, what is most striking about the book is how little its gay themes are concealed, particularly given the anxious moral standards of the time. Dorian leads a double life, unable to share the secrets he keeps; the male artist who paints him declares that he loves his youthful subject ‘madly, extravagantly, absurdly’ – something that seems to prefigure the very scandal that would bring down the author less than five years later.

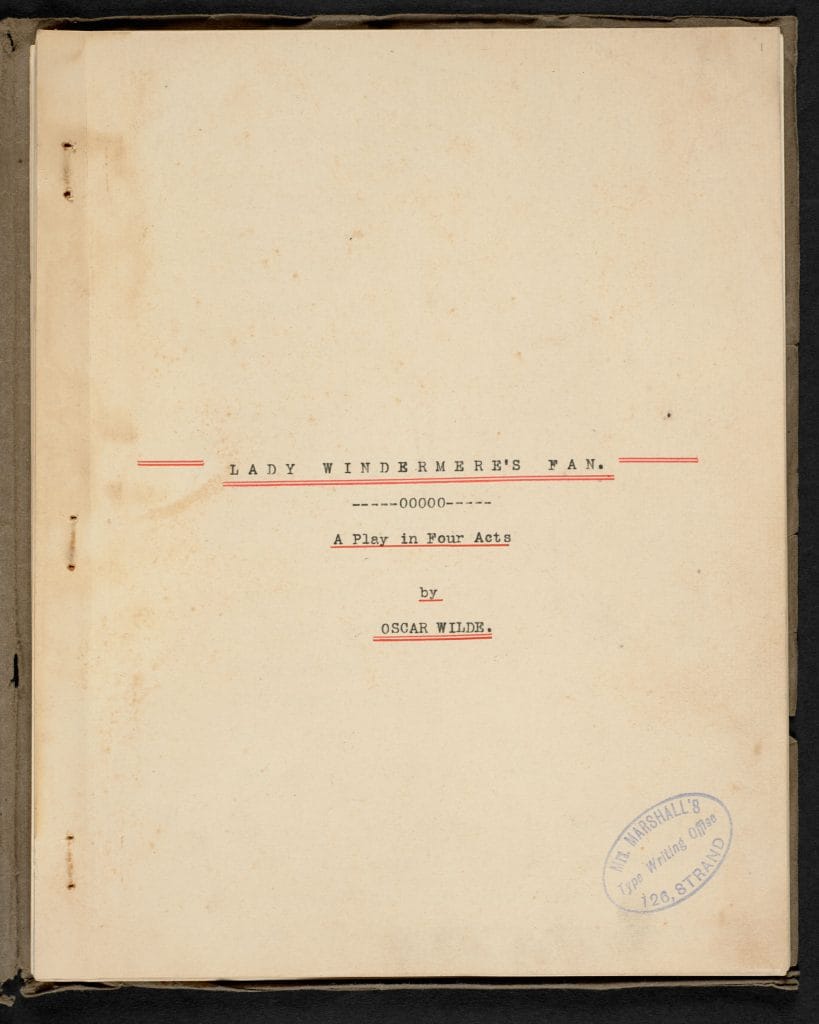

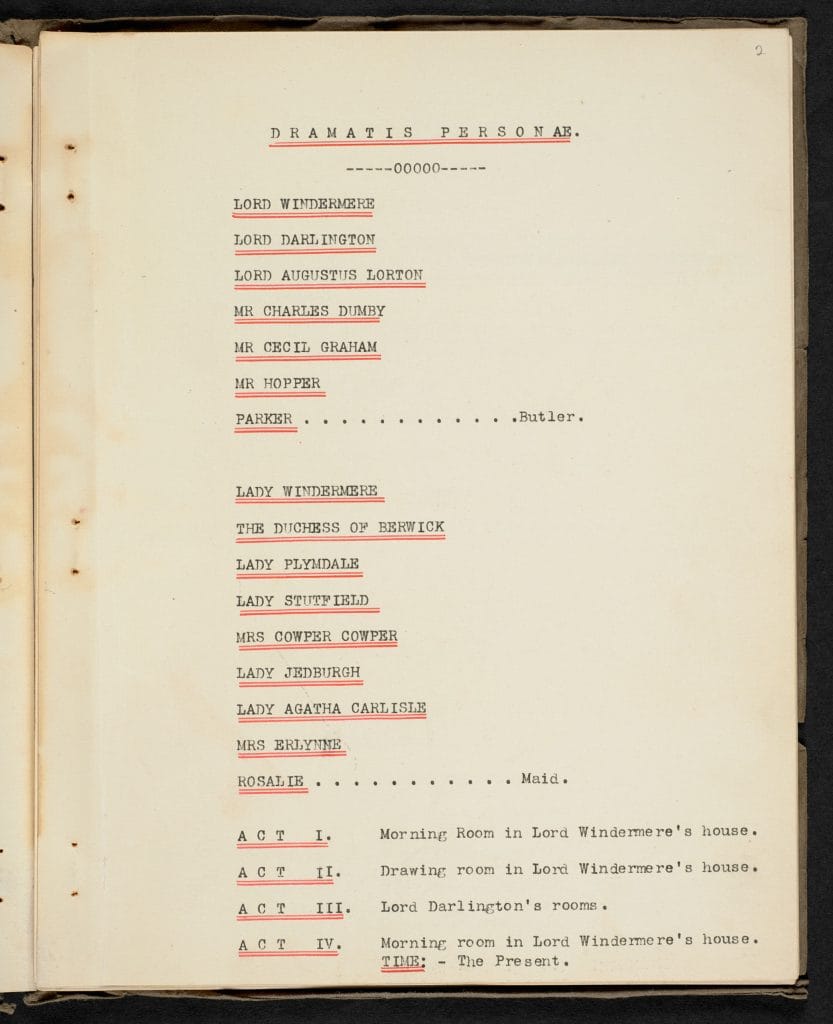

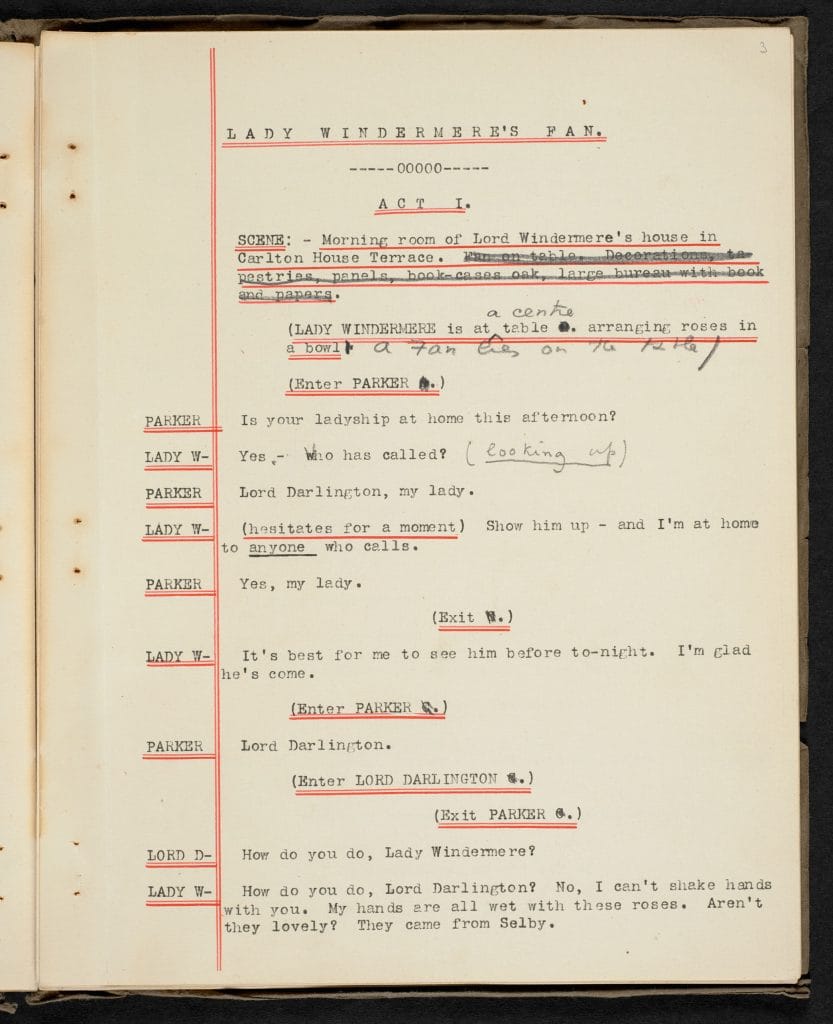

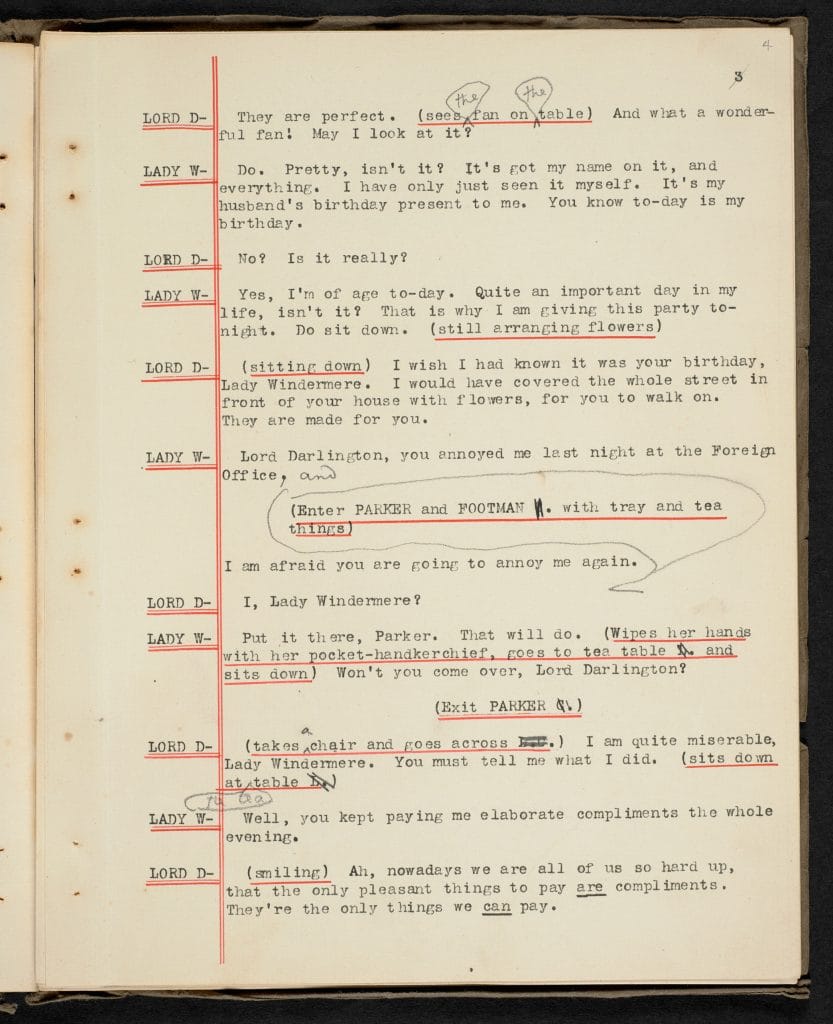

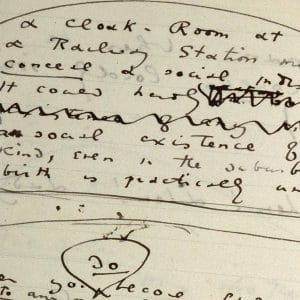

Wilde still had ambitions to become a dramatist. At around the same time as Dorian Gray appeared, he was finally persuaded to try his hand at writing a society comedy inspired by contemporary French drama, where plots full of social intrigues and unlikely twists were all the rage. In summer 1891 he began work on the script that became known as Lady Windermere’s Fan (part of it was written in the Lake District in the north of England, near Lake Windermere). Relating an enjoyably unlikely story of a wife who suspects her husband of having an affair, only for the ‘other woman’ to be unmasked as her own mother, the drama was a hit on the London West End the following year. It was the dramatic success Wilde had long craved. One reviewer declared, ‘Mr Oscar Wilde is nothing unless brilliant and witty’.

The plays that followed made Wilde one of the most renowned playwrights of the age. A Woman of No Importance (1893) focuses on a woman who was abandoned by her high-society lover when she became pregnant, satirising class and sexual double standards in Victorian England. An Ideal Husband (1895) questions what ‘ideal’ in marriage really means (the husband in question, a leading politician, is shown to have a murky past, a subject that was clearly on Wilde’s mind). Despite their intricate plots and witty dialogue (few are better than Oscar Wilde at deploying scintillating one-liners) the plays have a seriousness that belies their comedy. One character’s assertion in An Ideal Husband that ‘morality is simply the attitude we adopt towards people we personally dislike’ may take aim at Victorian hypocrisy, but it rings true even now. The play prompted the dramatist George Bernard Shaw to call Wilde ‘our only thorough playwright. He plays with everything: with wit, with philosophy, with drama, with actors and audience, with the whole theatre’.

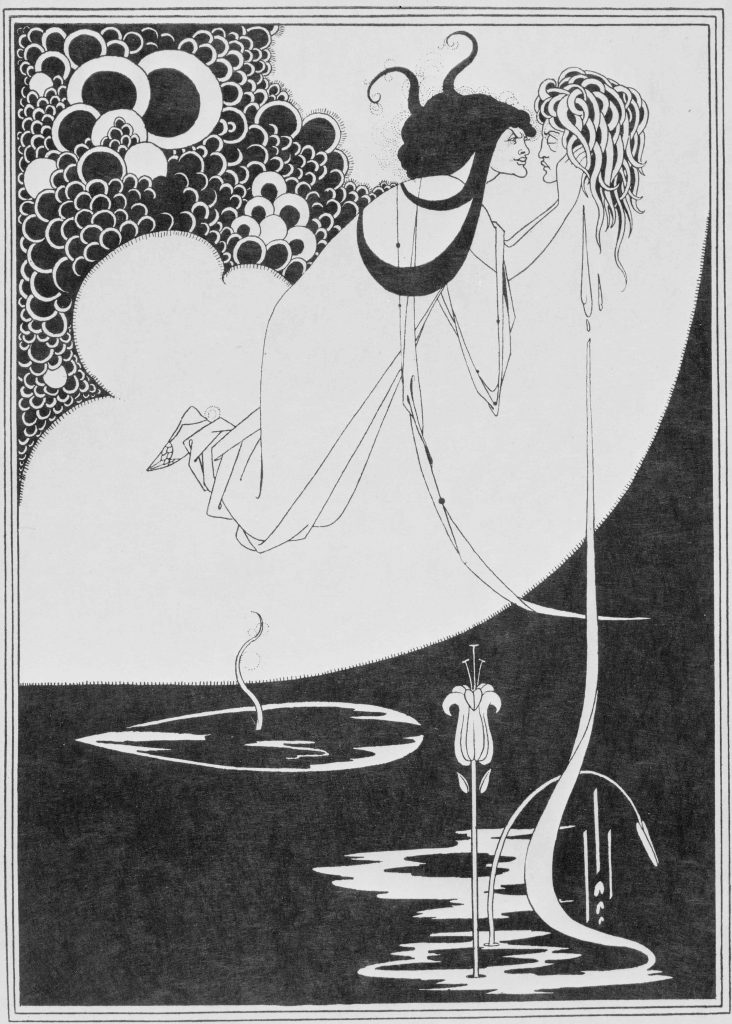

Wilde showed that he could master tragedy, too, as demonstrated in his melodrama Salomé, on which he began working in that miracle year of 1891. Originally written in French, the play relates the Bible story of a dancer who falls in love with John the Baptist, only to be rejected by him. Infuriated, Salomé demands that John be executed and his head brought to her on a silver platter (as Wilde would later write: ‘each man kills the thing he loves’).

Yet again, Salomé caused controversy: the play was banned by the British authorities, supposedly because it depicted Biblical characters, and it was not finally staged until 1896. A published version appeared in 1893, with sensuous illustrations by the renowned artist Aubrey Beardsley.

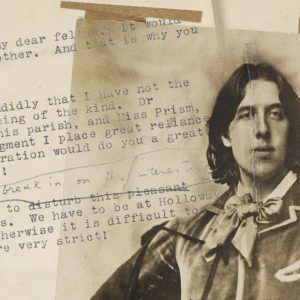

In February 1895, less than a month after the debut of An Ideal Husband, The Importance of Being Earnest, the play many now regard as his masterwork, opened in London. Filled with even more brilliant lines than before (‘If the lower orders don’t set us a good example, what on earth is the use of them?’; ‘All women become like their mothers. That is their tragedy. No man does. That’s his’; ‘ignorance is like a delicate exotic fruit; touch it and the bloom is gone’; ‘to lose one parent, Mr. Worthing, may be regarded as misfortune; to lose both looks like carelessness’), the play is blissfully funny. But it is also superlatively plotted, a madcap tale of mistaken identities and apparently doomed romance that rivals anything written by Shakespeare or the 18th-century playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan for ingenuity. Despite being one of the funniest comedies ever composed in English, it also says profound things about human identity. It has been called the second most known and quoted play after Hamlet.

Wilde’s trial and final years

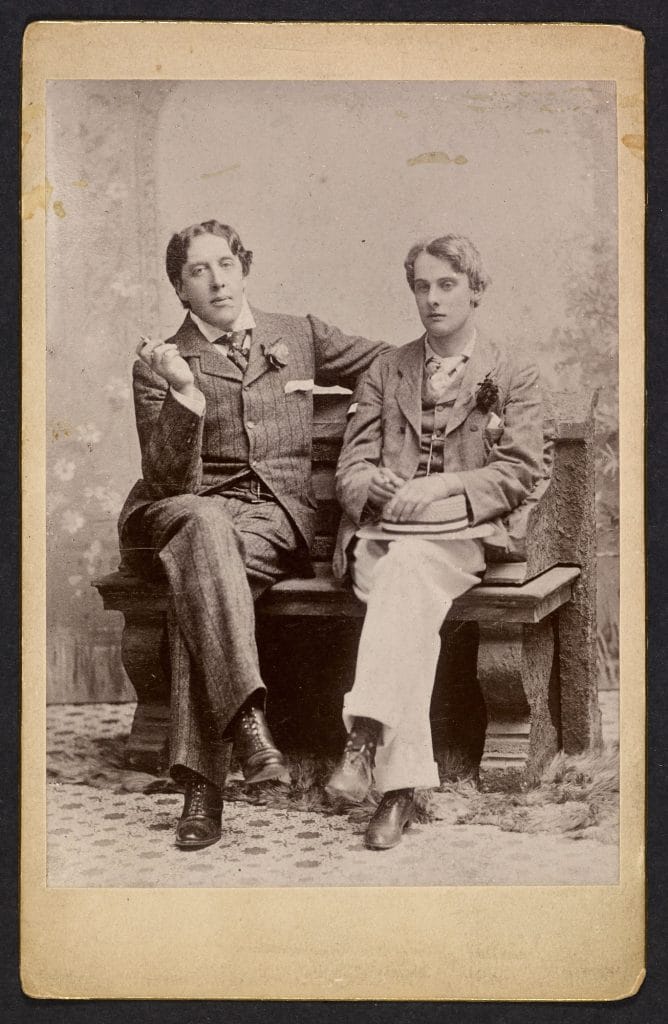

Creatively, the early 1890s were a remarkable period for Wilde, but clouds were gathering. His marriage was under pressure, and in 1891 he met and began a sexual relationship with Lord Alfred Douglas, a young and startingly good-looking aristocrat. Wilde seems to have fallen hard for Douglas (nicknamed ‘Bosie’), and via him was introduced to London’s gay scene – very much an underground world, because relationships between men were illegal in Victorian England, and would in fact remain so for another 60 years. Anyone accused of homosexual ‘gross indecency’ faced imprisonment and social disgrace.

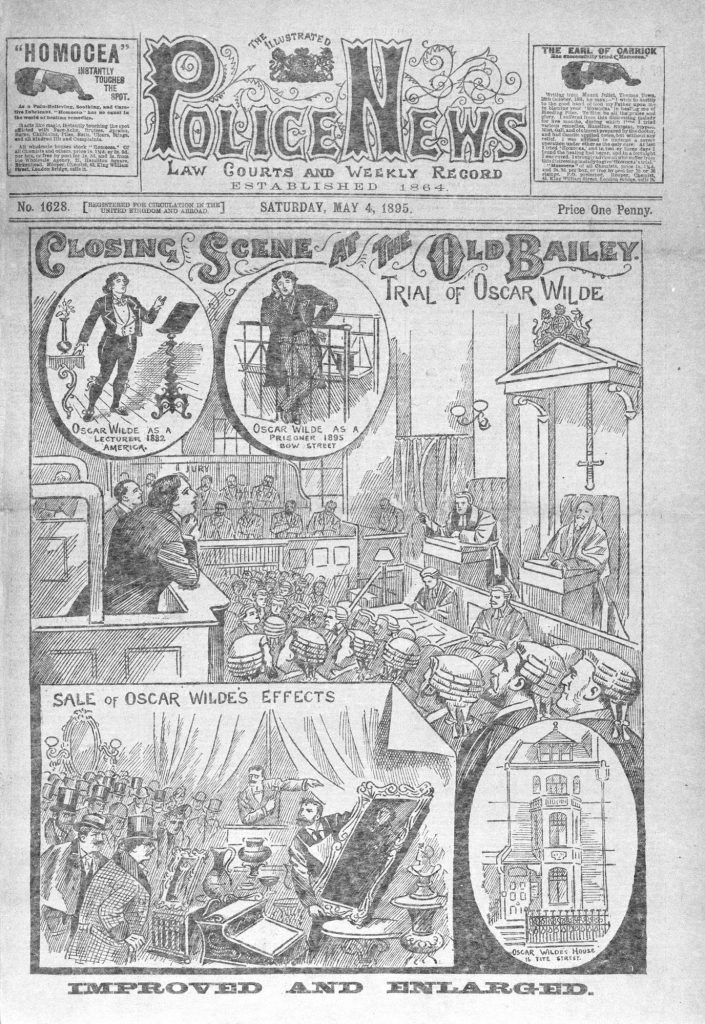

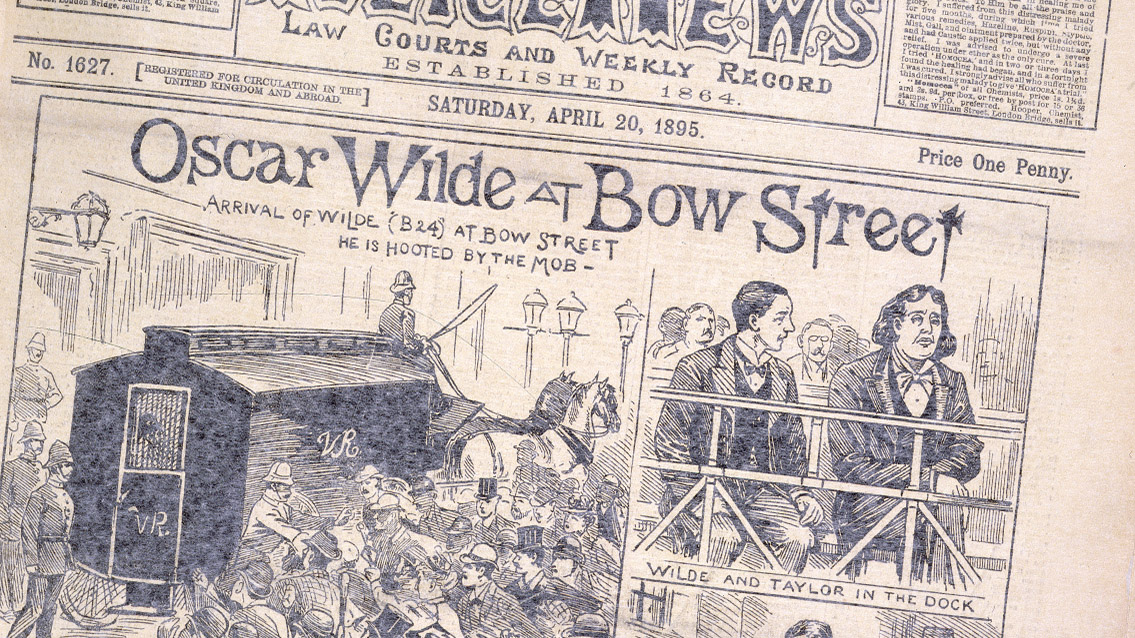

Hearing of the affair, Alfred Douglas’s father, the Marquis of Queensberry, wrote to Wilde, calling him a ‘ponce or somdomite’ (farcically, he misspelt the word ‘sodomite’). Wilde sued him for libel – a risky decision that resulted in a court case. Despite a courageous appearance in the witness box, where he found himself having to defend not only his love life but his writings on love and desire, the author eventually lost and was sentenced to two years’ hard labour in prison.

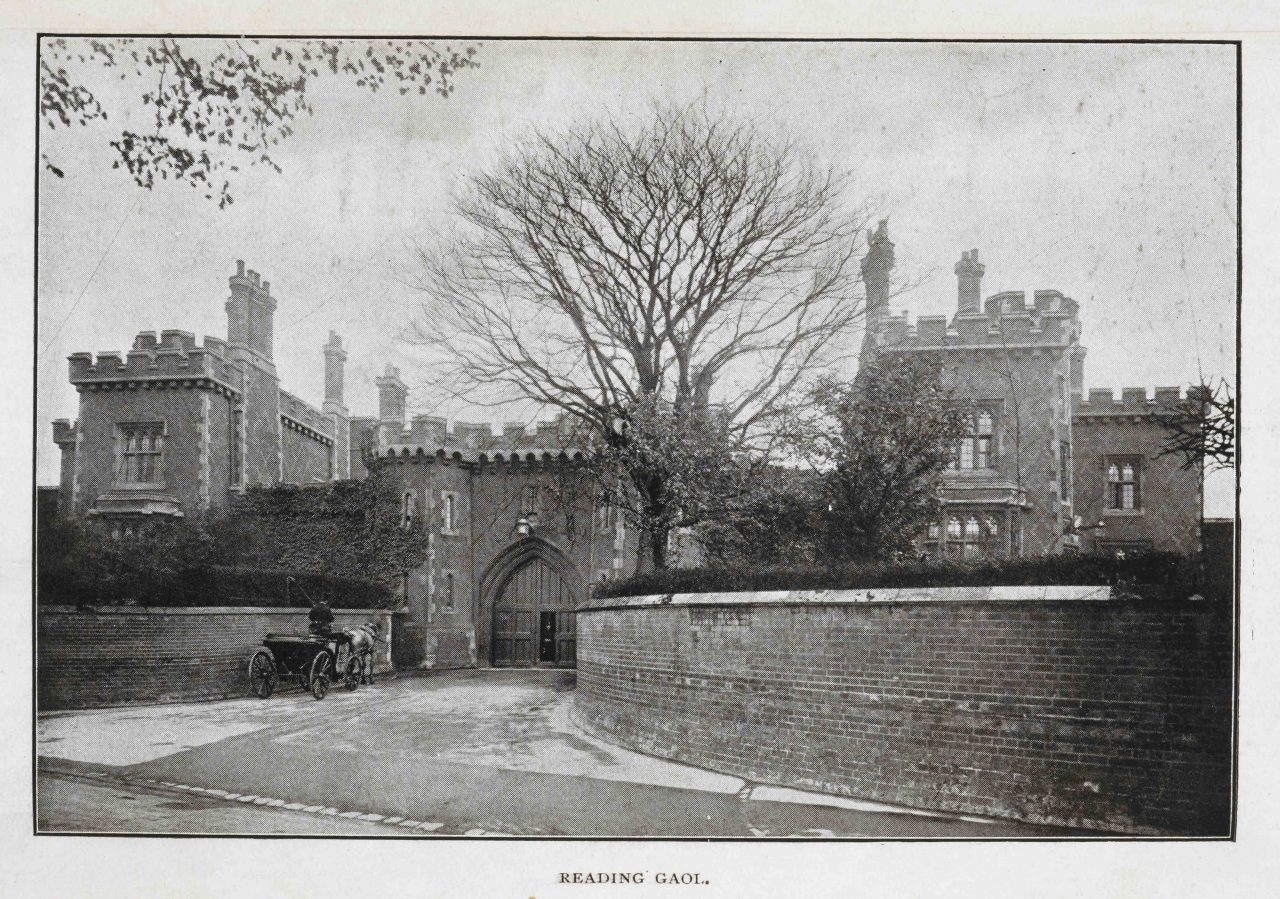

Wilde found the experience crushing, particularly when he was sent to Reading jail, west of London, where conditions were poor and he was physically attacked by other inmates. He struggled to adapt, and was declared bankrupt, meaning that Constance and the children – she refused to divorce her husband – lost their house and nearly all their possessions. Wilde was eventually released in 1897. In 1898, he published The Ballad of Reading Gaol, a sombre, halting poem that glances wistfully at what might have been.

Yet perhaps the greatest product of his prison experience is the work now known as De Profundis, meaning ‘From the Depths’, a quotation from the Biblical Psalms. The work is a 55,000-word letter to Douglas dwelling on love, loss, bitterness, sorrow and much else besides. ‘Most people live for love and admiration,’ Wilde writes, ‘but it is by love and admiration that we should live.’ Elsewhere, speaking directly to Douglas, he admitted, ‘Of course I should have got rid of you.’ It has often been called the greatest love letter ever written.

Although Wilde left for France as soon as he was released, his health and creative spirit were broken. He spent his final few years shuttling around Europe. The kindly prison governor at Reading – who had encouraged him to write De Profundis and given him the pen and paper to do so – remarked that ‘like all men unused to manual labour who receive a sentence of this kind, he will be dead within two years’. So it proved. In November 1900, Wilde was suddenly taken ill and died in a cheap Parisian hotel. He is buried in the famous Père Lachaise cemetery in the city.

Wilde’s legacy

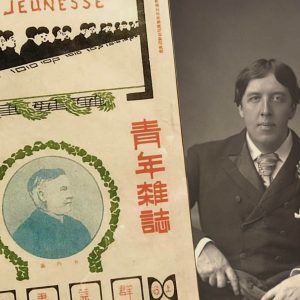

In the 120-odd years since Oscar Wilde died, his reputation has undergone as many revolutions as those he experienced during life. Despite being almost totally ignored in Britain in the years following his death – the causes of his downfall meant that he was a highly controversial figure – he was feted in countries as varied as France, the US and Russia. Even in Britain, his plays remained popular. Wilde’s profile was boosted in 1908 by the publication of a collected fourteen-volume edition of his works by his friend and former lover Robbie Ross.

From the 1960s onwards, his work was increasingly seen in a fresh light – interpreted as a serious author worthy of university study. Following the decriminalisation of homosexuality in Britain in 1965, Wilde became an icon for a new generation, passionate about sexual freedom and civil liberties. As an author, he has left his mark on writers as varied as the playwrights Noël Coward and Tom Stoppard (who has repeatedly referenced Wilde’s work), the American novelists Armistead Maupin and Edmund White, and countless more.

Even for people who have never seen one of his plays or read one of his stories, Wilde’s name remains a potent symbol. Not only has his life been used to campaign for gay and sexual rights across the globe, his own actions demonstrate how important it is to stand up for what you believe – even if the odds against you seem overwhelming.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Andrew Dickson

Andrew Dickson is an author, journalist and critic. A former arts editor at the Guardian in London, he writes regularly for the paper and appears as a broadcaster for the BBC and elsewhere. His new book about Shakespeare’s global influence, Worlds Elsewhere: Journeys Around Shakespeare’s Globe, was published in 2015. He lives in London, and blogs at Worlds Elsewhere.