‘… [A]s much soul … and full as much heart’: Translation and Reception of the Brontë Sisters in China

This article tells the story of the Brontë sisters in China since the first translation of Jane Eyre was published in 1925. It charts the rise, fall and rise of their literary fortunes in China, where they are now read, studied and beloved as if they were the Chinese very own.

In June 2009, Jane Eyre, a spoken drama [话剧] based on the novel by Charlotte Brontë, debuted at the grand new National Centre for the Performing Arts (国家大剧院) in Beijing. Many in the audience were moved to tears by the story of the young governess as she struggles to stake out a place of independence and dignity for herself. When interviewed, Chen Shu [陈数], who starred in the title role, said that she had read the novel when she was a 14-year-old student at a dance school, and that as an awkward teenager she identified with the protagonist ‘because of the quiet suffering, the lack of love, care and respect’. If deep in Chen Shu’s heart there lurked a Jane Eyre as she rehearsed and performed the title role, there is probably a Jane Eyre in the hearts of countless Chinese readers who have got to know her and her story, told and retold through the decades since the Brontë sisters were first introduced to China in the early 20th century.

The earliest translations of works by the Brontës

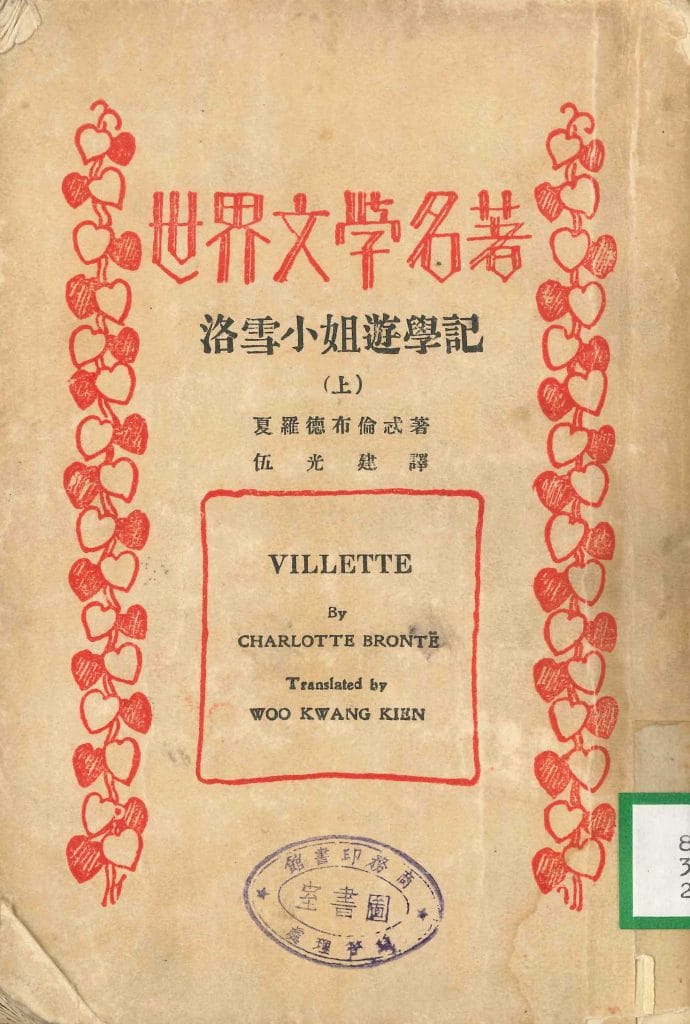

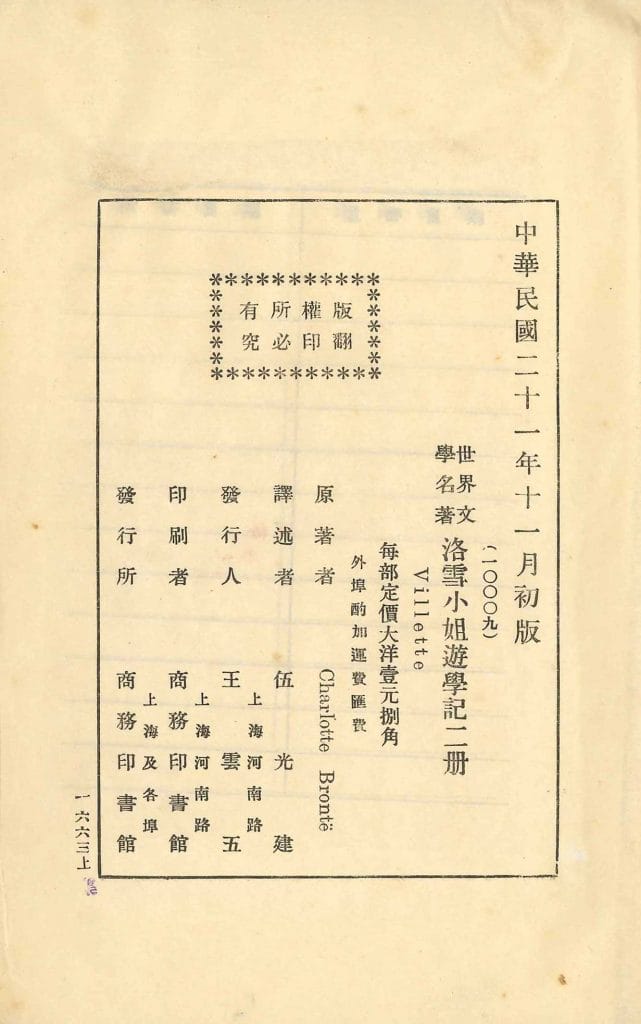

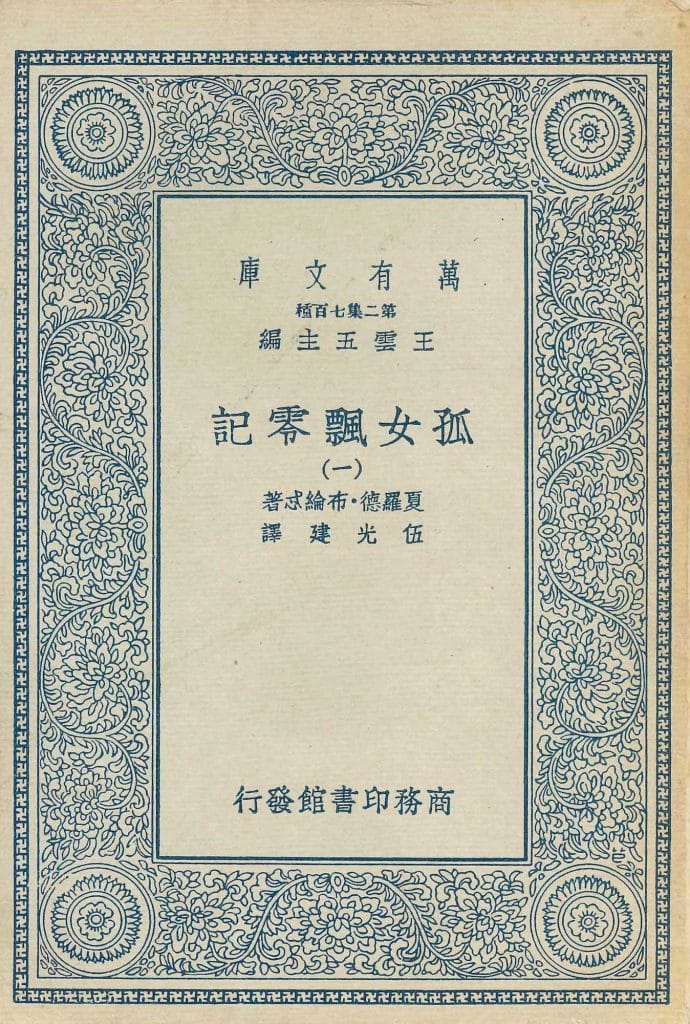

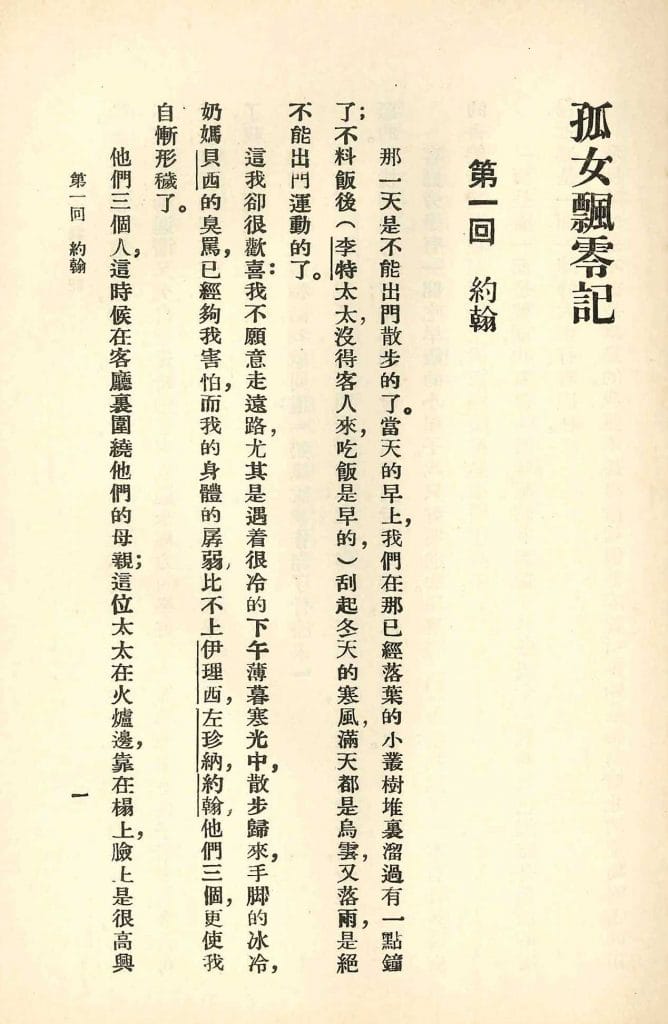

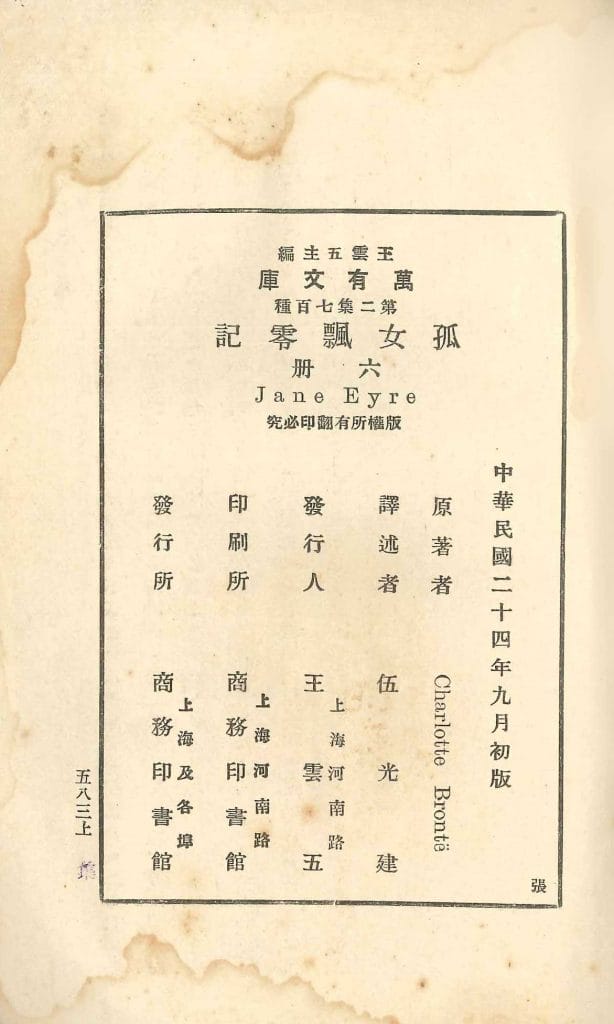

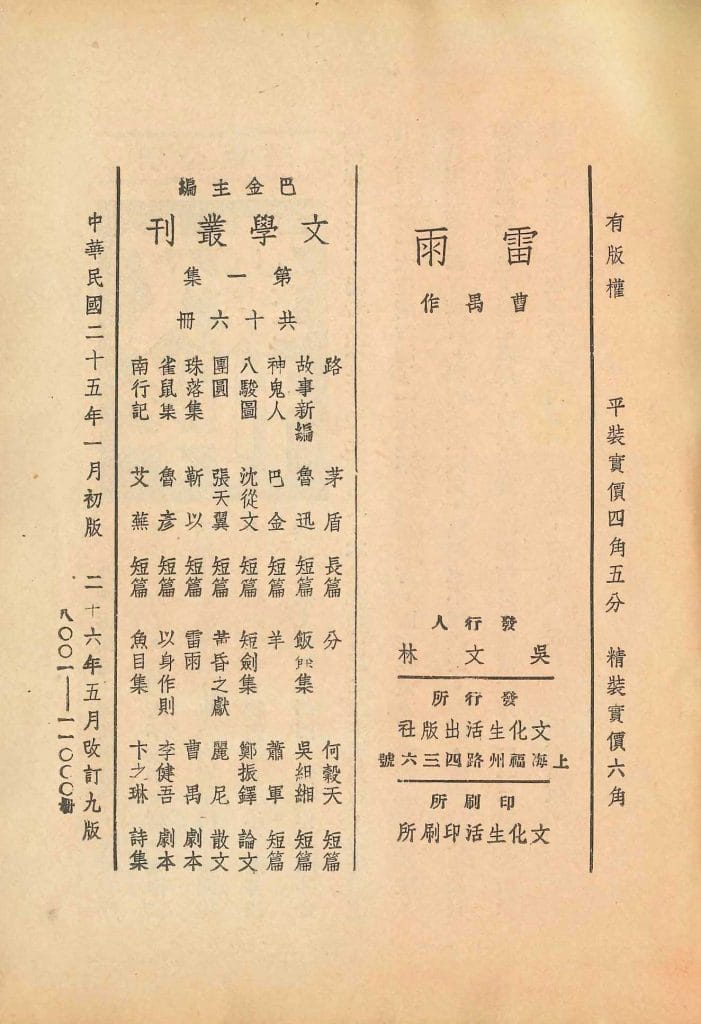

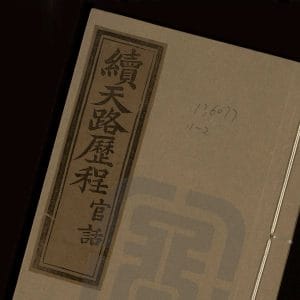

The first Chinese translation of the Brontës was published in Shanghai in 1925. It was an abridged rendition of Jane Eyre [重光记] by Zhou Shoujuan (周瘦鹃1895–1968), a popular Mandarin Ducks and Butterfly School [鸳鸯蝴蝶派] writer, who cherry-picked and scaled the novel down to a simple love story. The first full-text Brontë translation was Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights [狭路冤家] by Wu Guangjian (伍光健1867–1943) in 1930, which he followed with a translation of Villette [洛雪小姐游学记] in 1932 and an abridged translation of Jane Eyre [孤女飘零记] in 1935. As indicated in a brief note for his Jane Eyre rendition, Wu had chosen this novel to translate because it ‘tells the love story of a woman whose noble spirit refuses to be seduced by wealth and crushed by power – the noblest spirit of womankind’.

Within a year of Wu Guangjian’s abridged rendition of Jane Eyre, a major full-text translation by Li Jiye (李霁野1904–1997) would arrive on the scene. Adopting the ‘direct’ translating method promoted by his mentor Lu Xun (鲁迅1881–1936), Li chose 简爱 [‘Simple Love’] for the Chinese title of his translation, a smart transliteration that all but captures the pathos and essence of the story as well as the phonetics of the original title – although the love between Jane and Rochester, complicated by class, gender and a messy cluster of other determinants, is anything but simple.

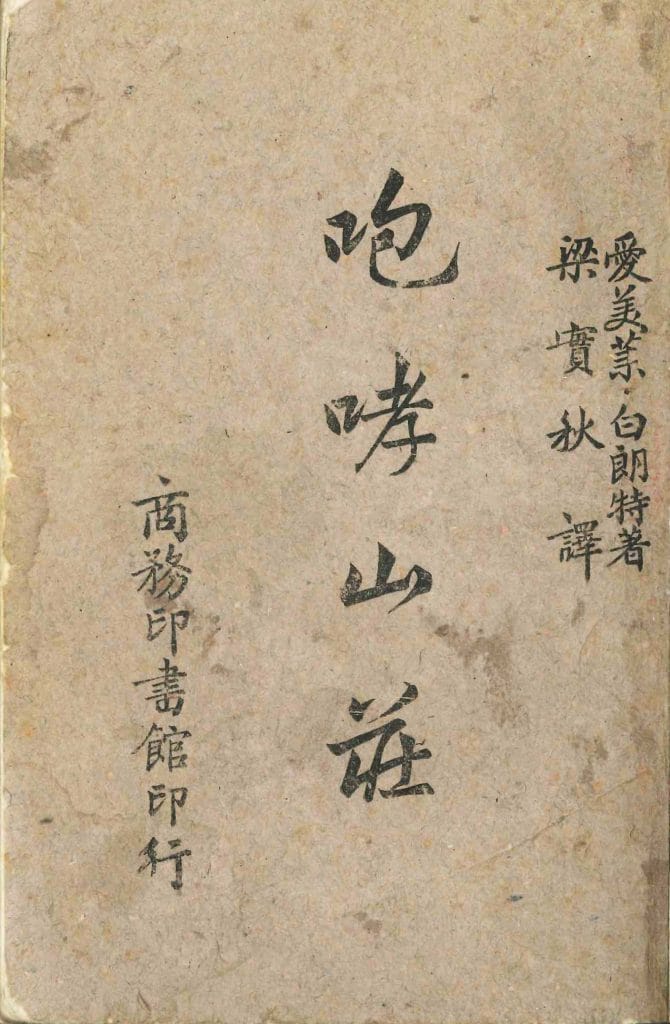

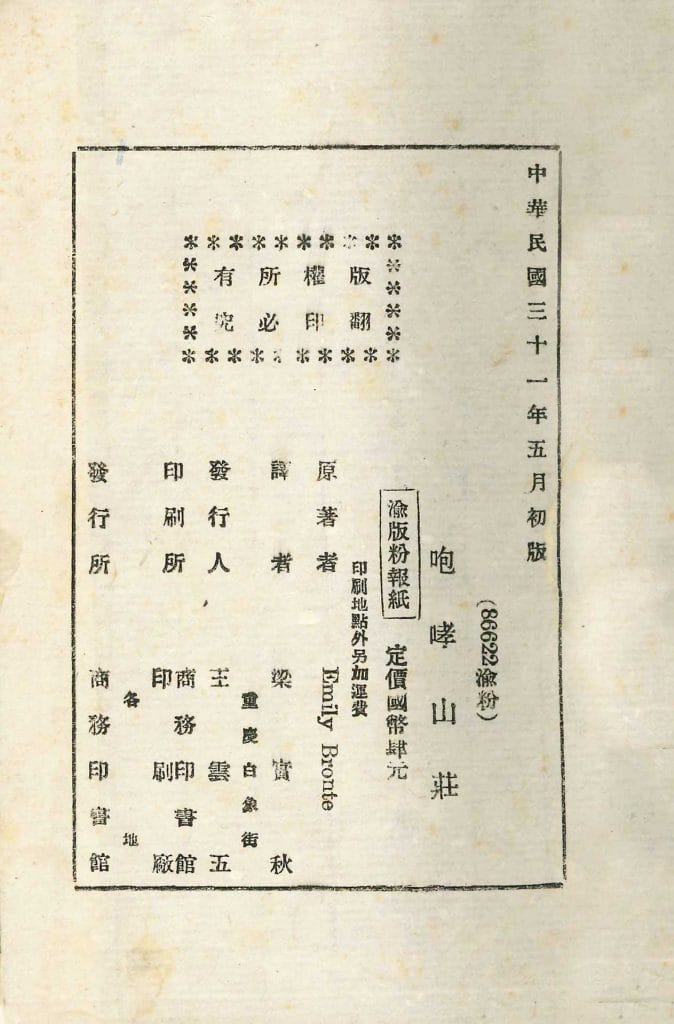

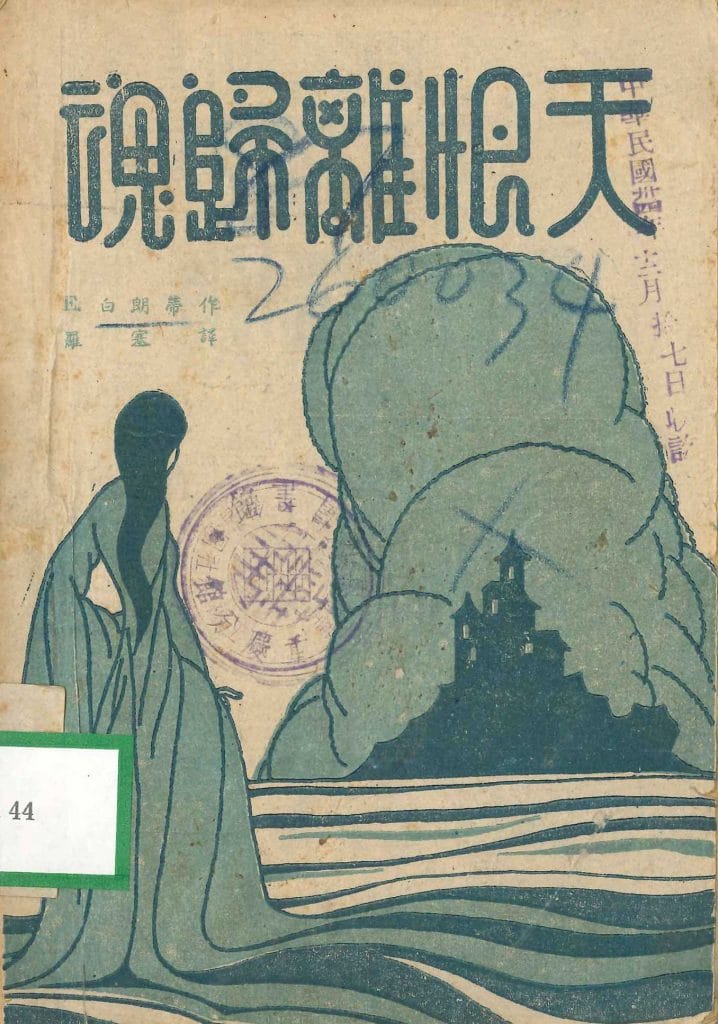

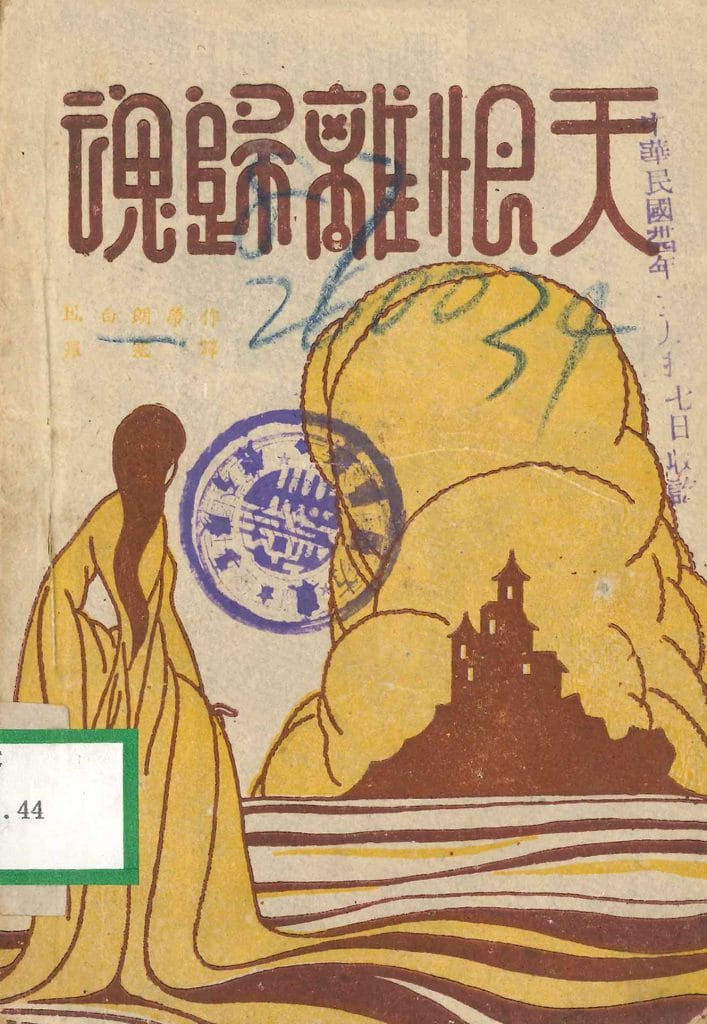

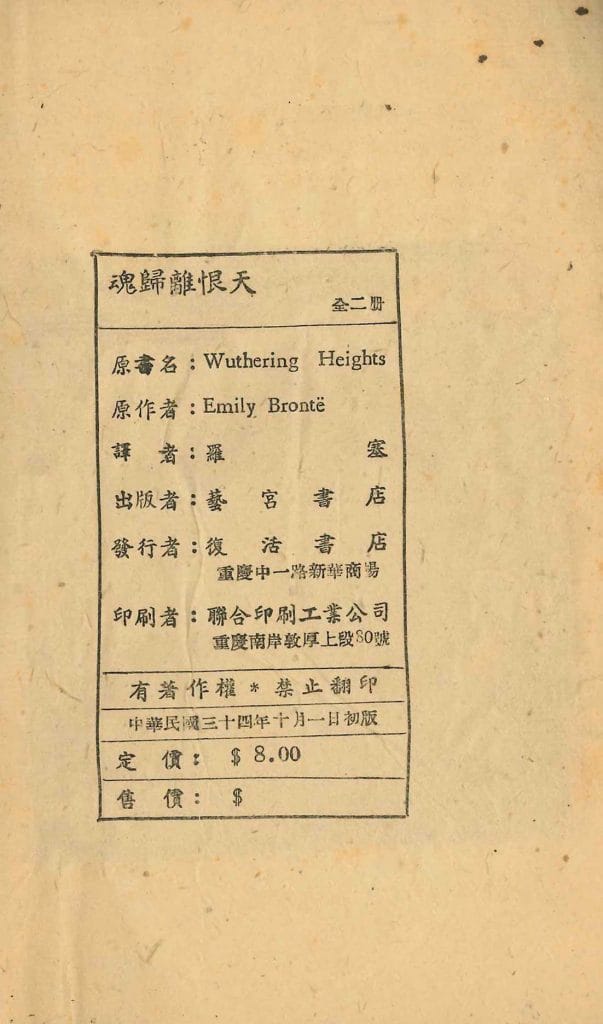

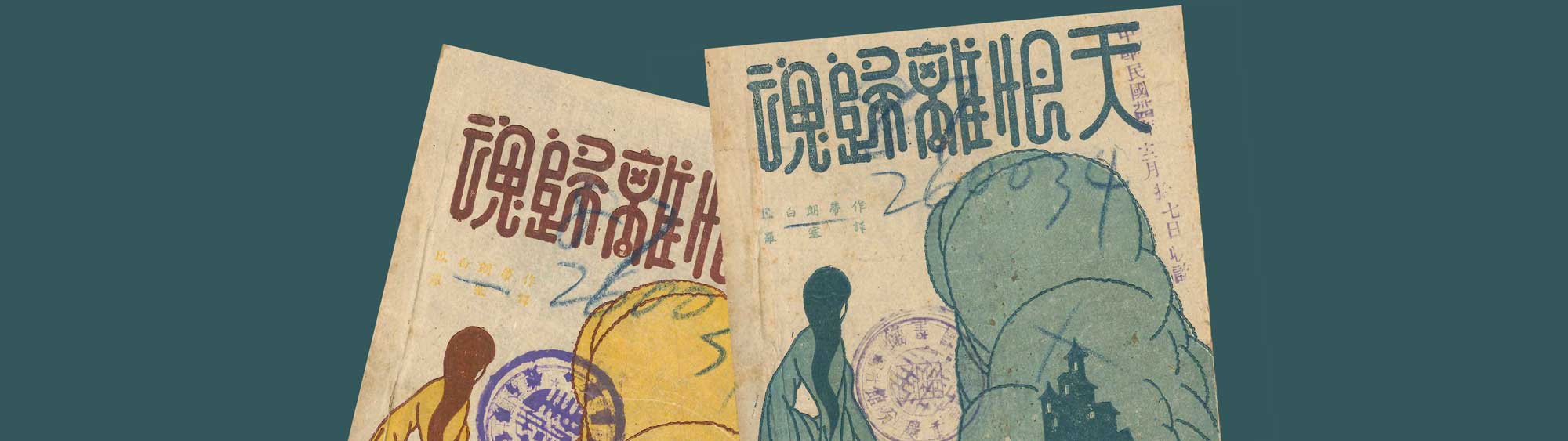

Wu’s 1930 translation of Wuthering Heights paved the way for three other notable full-text endeavours, each with a curious Chinese title that sought to capture the sound, the sense and the spirit of the original: 咆哮山庄 by Liang Shiqiu (梁实秋1903–1987) in 1942, 魂归离恨天 by Luo Sai (罗塞 no known biography) in 1946 and 呼啸山庄 by Yang Yi (杨苡 1919–) in 1955, with Yang Yi’s ingenious transliteration winning out and becoming the de facto Chinese title for all subsequent renditions of the novel.

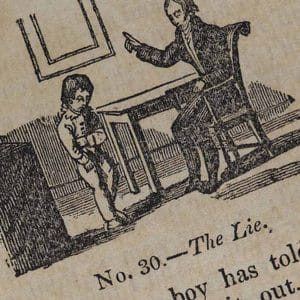

Jane Eyre and class consciousness

The Brontë sisters were first introduced, albeit briefly, to Chinese readers in a 1917 article about European and American women novelists published in a progressive women’s magazine. Ten years later, a female author of a history of modern European and American fiction celebrated Charlotte Brontë as ‘the greatest among women writers’. Such enthusiasm, however, was not shared by Mao Dun (茅盾1896–1981), an important figure in the May Fourth Movement (1919) who had been directly involved in the heated debates about what foreign literature to translate and how to translate it. Mao Dun felt strongly that in a country like China ‘where there is yet no mature “literature for humanity” [人的文学], translation is particularly important because without it what else could we use to cure the impoverished souls and remedy the flawed human nature?’ To Mao Dun and others, the story of a governess (a member of the oppressed and exploited class) winning the love of her aristocratic employer (a member of the decadent ruling class) had little to offer the pressing cause of cultural renewal and national survival. What China urgently needed instead was the bold, rallying figure of Ibsen’s Nora, who, once confronted with the truth about her seemingly perfect bourgeois life, has the courage to slam the door shut and leave.

As might be expected, the perceived ‘petty-bourgeois’ indulgences and absence of class consciousness in Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights would not help them fare well during the decades from 1949 to the 1970s.

Something interesting, though, did happen in 1975. One day, a copy of the 1970 TV adaptation of Jane Eyre (starring Susannah York and George C Scott) was couriered from Beijing to the Shanghai Film Dubbing Studio by express delivery, the package marked with a numeral code instead of the title of the film. Chen Shuyi (陈叙一), the studio director who had been denounced as a ‘black warrior’ of ‘feudal-bourgeois’ art, set to work right away in the utmost secrecy. His principal artists were Li Zi (李梓), who had dubbed the voice of Jane Eyre for the Chinese release of the 1943 Hollywood adaptation (starring Joan Fontaine and Orson Welles), and Qiu Yuefeng (邱岳峰), a condemned ‘historical reactionary’, chosen to channel Rochester through his smoky, magnetic voice. The instruction from Premier Zhou Enlai, much-maligned at the time, was that the dubbed film wouldbe used as an important reference work by ‘the Proletarian Command Centre to keep an eye on the latest in international class struggle’. Public screening of the TV movie, however, would have to wait until summer 1979. It was greeted enthusiastically by audiences as well as national newspapers such as China Youth, the Xinhua Daily and the Guangming Daily.

Post-Cultural Revolution reception

It was around this time that Zhu Hong (朱虹), an eminent Chinese Academy of Social Sciences scholar, penned the first scholarly piece on the Brontës in the post-Cultural Revolution era. Zhu Hong suggests that for a long time Charlotte Brontë’s novel had not been well regarded due to its ‘bourgeois individualism’ and its lack of critical reflection and exposure of the realities of capitalist society. However, even measured by the same ‘reflecting and exposing capitalist reality’ tenet, Zhu Hong contends, the Brontë novel has not done too shabby a job. The complex backstory – of Jane Eyre’s mother being disowned by her family for having married a poor clergyman; of Rochester being misled into marrying a psychologically unstable woman for her money only; the hardship young Jane endured at the Lowood School; and the fact that both Rochester and Jane Eyre inherited fortunes made in the West Indies, colonies of the British Empire, etc. – amounts to unmistakable criticism of the cruel-heartedness of bourgeois society, the corruption of its charity establishment and the hypocrisy of upper-class men. The most redeeming quality of the novel, however, is the story of Jane herself, the soul of the entire book, who gives full-throated expression to gender issues, long before Ibsen’s A Doll’s House.

Popular and scholarly success

Since then, the Brontë sisters have seen their literary fortunes in China rise impressively. According to a study from October 2011, a total of 167 Brontë books were on the market at the time, the collective output of the endeavours of 87 translators and 88 publishing houses. Of these, 94 were various editions of Jane Eyre, there was one edition of Shirley (also by Charlotte Brontë), 66 editions of Wuthering Heights, one edition of Agnes Grey (by Anne Brontë, the youngest of the sisters), one edition of the combined works of the Brontë sisters (Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey), one biography each of Charlotte and Emily and one scholarly book each on Charlotte and Emily.

And since then, hundreds of articles on the Brontë sisters have been published in scholarly journals. They range from character analyses to studies of religion, mythology, style and imagery (e.g. moon and fire in Jane Eyre, windows in Wuthering Heights). Their novels have been compared to a mélange of Western (e.g. Tess of the D’Urbervilles, Anna Karenina, Pride and Prejudice, Lady Chatterley’s Lover) and Chinese works. One study, for example, compares Bertha, the ‘madwoman’ in Jane Eyre, with Fanyi [繁漪], the repressed wife in Cao Yu’s play Thunderstorm [雷雨], written and first staged in the 1930s. Other studies find interesting intertextual comparisons between Emily Brontë’s novel and Spirit Return in Sorrow to Heaven [魂归离恨天], a screenplay by Zhang Ailing (张爱玲Eileen Chang) which has been dubbed the Chinese Wuthering Heights. Another Chinese writer who has been compared with the Brontë sisters is Chiung Yao (琼瑶1938–), the comparison resting on the fact that all of her novels also tell stories of the ‘noblest and purest’ [至真至纯] love.

Indeed the Brontë sisters are now much at home in a land and culture that they never had a chance to visit in their short, interrupted lives, but where they are well loved and enthusiastically studied.

‘as much soul … and full as much heart’

The 2009 spoken drama adaptation of Jane Eyre alluded to earlier features extensive use of modern, expressionist techniques (of sound and light), and so the story unfolds fluidly from the ‘present’ (Thornfield Hall) to the ‘past’ (Gateshead and Lowood School) and the ‘future.’ By summer of 2012 the critically acclaimed play had had a successful run for seven seasons – 54 performances in all. In fall 2016, Jane Eyre saw a major revival production at the same National Centre for the Performing Arts in Beijing. Just imagine for a moment Charlotte Brontë in the front row in the company of her beloved sisters as the story she had envisioned back in the 1840s, of a young woman who demands respect because she has ‘as much soul … and full as much heart’ as any man, came alive on the stage, and as audiences in the packed theatre, mesmerised, breathed together in the confluence of beauty and shared humanity. It would be interesting to know if she thought the Chinese adaptation had as much ‘soul’ and as much ‘heart’ as her original novel.

The text in the article is © Dr Shouhua Qi. It may not be reproduced without permission.

撰稿人: Shouhua Qi

Dr. Shouhua Qi is Distinguished Visiting Professor at the College of Liberal Arts, Yangzhou University and Professor of English at Western Connecticut State University. Among Qi’s most recent publications are The Bronte Sisters in Other Wor(l)ds (coeditor and contributing author, 2014) and Western Literature in China and the Translation of a Nation (2012), both published by Palgrave MacMillan. Qi is working on a book titled Adapting Western Classics for the Chinese Stage (to be published by Routledge in 2018).