Oscar Wilde and Victorian Fashion

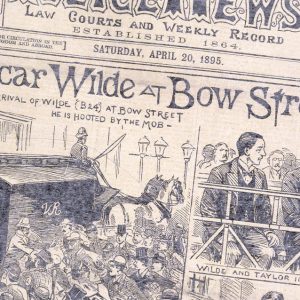

Irish poet and novelist Oscar Wilde was one of the most popular playwrights of the London stage in the early 1890s, and was well known for his bon mots that poked fun at high society. Fashion historian Amber Butchart explores his relationship with fashion.

How did Oscar Wilde’s style differ from conventional Victorian fashion?

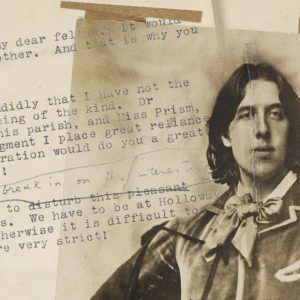

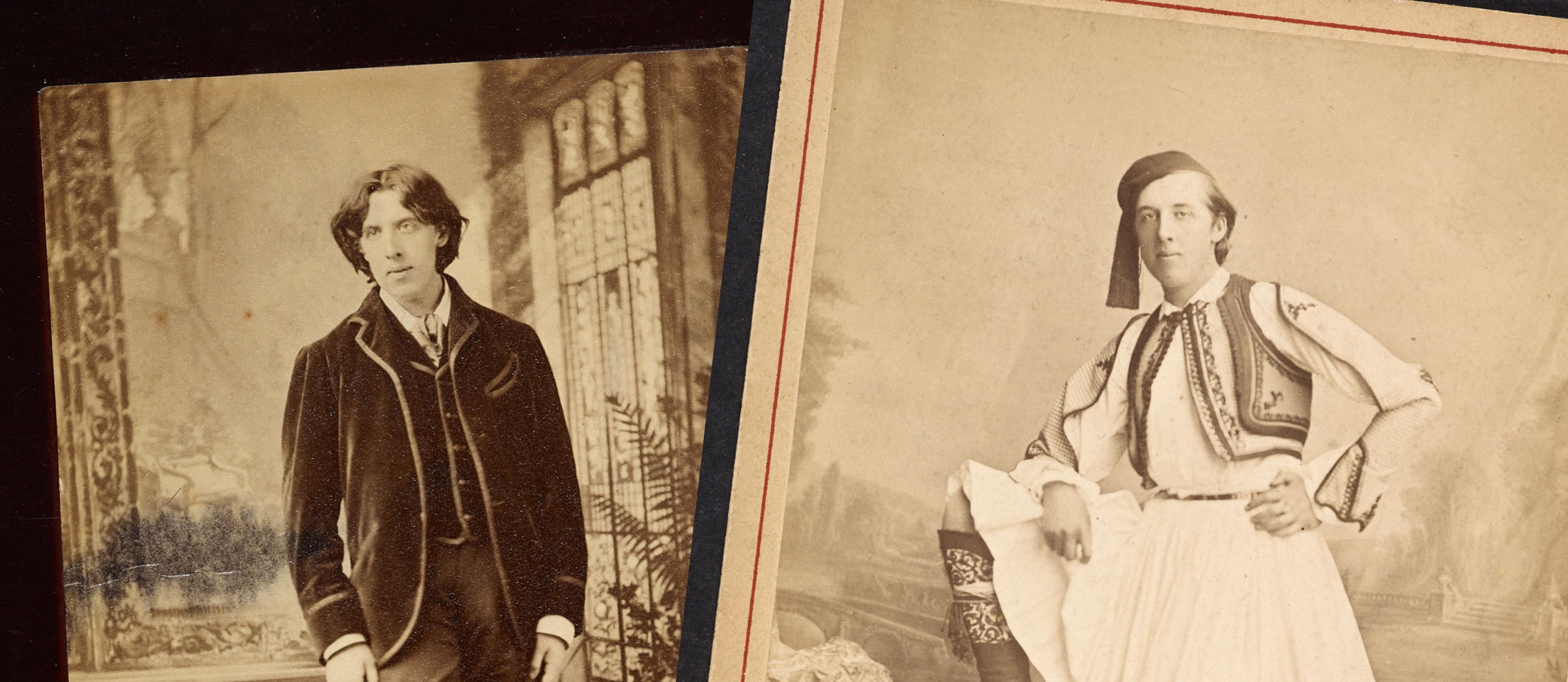

Wilde famously led his life in pursuit of beauty, in opposition to what he saw as bourgeois Victorian values. He was a key proponent of the Aesthetic Movement whose philosophy was guided by the principal, ‘art for art’s sake’. This was the idea that art should be judged purely for the pleasure it induces in the observer rather than for the moral message it conveys. After arriving in London in the late 1870s, Wilde became as notorious for his dress as for his wit and words, captured in his aphorism, ‘One should either be a work of art or wear a work of art’, from a lecture in 1884.

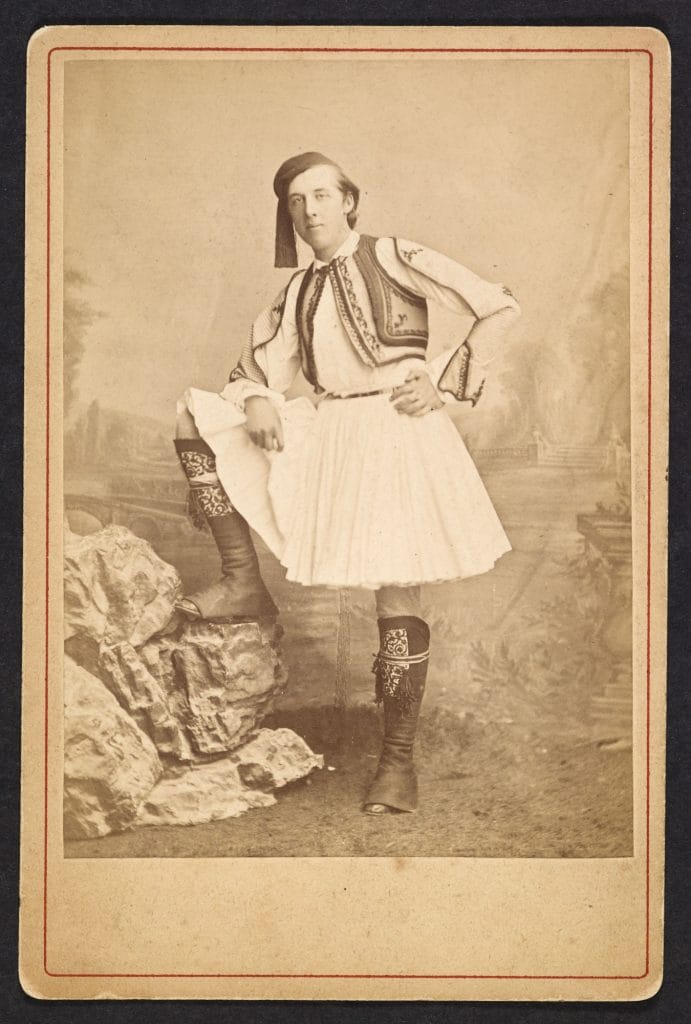

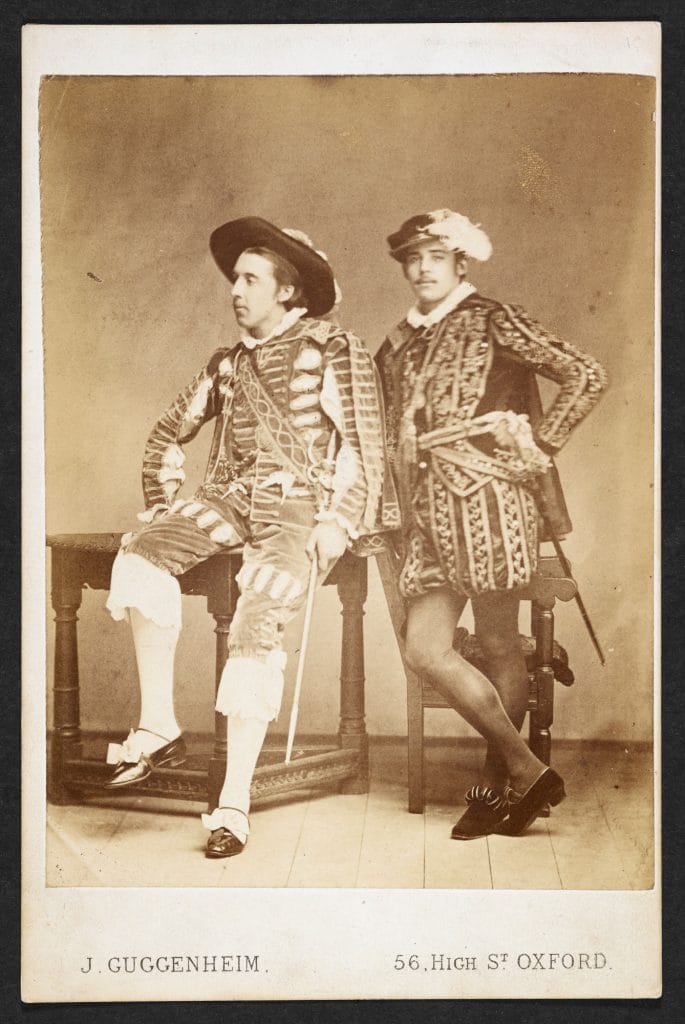

This was manifested in Wilde’s wardrobe through an interest in historical styles, such as knee breeches and stockings, and affected accessories from sunflowers to green carnations in his buttonhole. Wilde later turned to a more simple mode of dress and embraced Dandyism.

What did Wilde write about fashion?

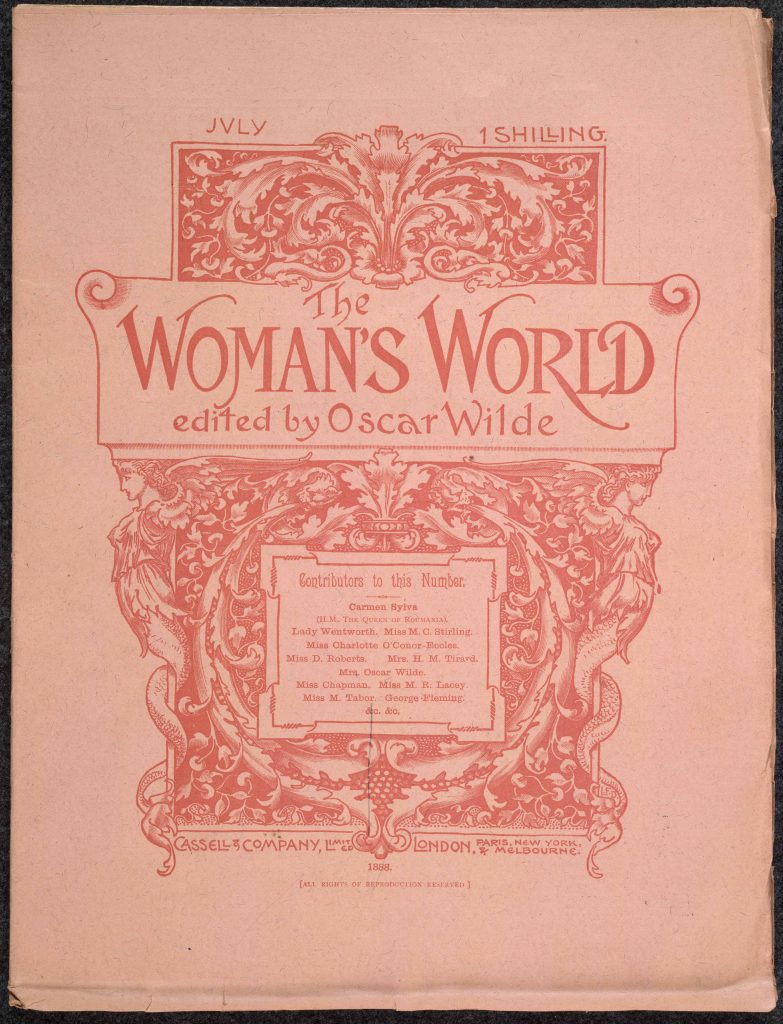

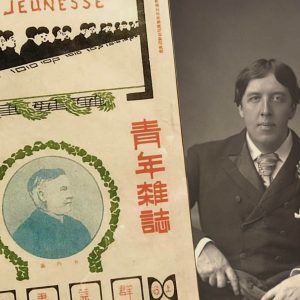

For two years from 1887 Wilde edited a women’s periodical. Under his editorship he transformed the Lady’s World: A Magazine of Fashion and Society into the intellectually driven and artistic title the Woman’s World, which his wife Constance also wrote for.

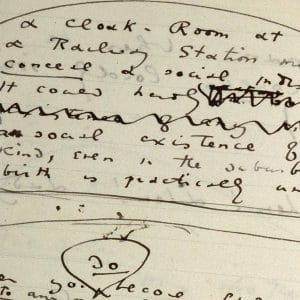

Wilde made his feelings about conventional fashion clear in an article penned for the New York Tribune in 1885, titled ‘The Philosophy of Dress’: ‘Fashion is ephemeral. Art is eternal. Indeed what is a fashion really? A fashion is merely a form of ugliness so absolutely unbearable that we have to alter it every six months!’

What was notable about Aesthetic Dress?

Aesthetic Dress was characterised by a return to pre-industrial dyes and techniques, and a rejection of the tight-laced corset of Victorian fashion. Aestheticism was a reaction against conventions of the day, and had some high profile followers, as well as key shopping destinations. The department store Liberty, founded in 1875, became a crucial space for the Aesthetic shopper. The founder imported textiles from Japan, China and the Middle East, which were often dyed in Britain and which satisfied a more artistic clientele.

The association of Liberty with Aestheticism was so clear that when the Gilbert and Sullivan comic opera Patience premiered in 1881, which satirised the Aesthetic movement (including Wilde), the costumes were made from Liberty fabrics, and these fabrics were even advertised in the programme. The character Archibald Grosvenor was a parody of Wilde, and the comic opera included the lines: ‘Though the Philistines may jostle, you will rank as an apostle in the high aesthetic band, If you walk down Piccadilly with a poppy or a lily in your medieval hand’.

Victorian Fashion and the Birth of Couture

The 19th century saw the development of the couture industry in France. By 1895 there were over ten times as many couturiers listed in Paris as there had been in 1850. This blossoming of couture is often linked to Charles Frederick Worth, who styled himself as an artist-creator: the ‘grand couturier’. Originating in Lincolnshire in Britain, Worth opened ‘Worth et Bobergh’ in Paris with his Swedish partner in 1858. Worth was an early adopter of a number of elements that today define high fashion, from using a label as luxury goods branding to using live models for his creations (often his wife Marie) and creating seasonal collections in line with the social calendar.

Wilde was not a fan of this style of Parisian couture, believing that clothing should be beautiful but practical. He wrote, ‘The gorgeous costumes of M. Worth’s atelier seems to me like those Capo di Monte cups, which are all curves and coralhandles, and covered over with a Pantheon of gods and goddesses in high excitement and higher relief; that is to say, they are curious things to look at, but entirely unfit for use’.

What was Victorian Dress Reform?

Victorian fashion was restrictive and highly formalised for both women and men. The etiquette of dress held a great deal of social importance; clothing was a way to display your wealth and status conspicuously. Some groups throughout the century used dress as a battleground for different ideas.

The American temperance and women’s rights campaigner Amelia Bloomer advocated women wearing bifurcated, or baggy, ‘Turkish’-style trousers under knee-length skirts in the 1840s and 50s. Women were so enthusiastic that the items became known as ‘Bloomers’. Amelia was concerned about the constraining effects of long, heavy, full skirts, and saw this alternative clothing as a hygienic and practical solution. But the popular press in the US and the UK ran so many anti-Bloomerism pieces that she renounced the style as it was distracting attention away from her political goals such as fighting for the right to vote and for the right to property ownership.

In Britain, the Rational Dress Society was established by Lady Harberton in 1881. A big fan of cycling, Lady Harberton also believed clothing should be non-restrictive and practical. As such she favoured boneless stays over tight-laced corsets, and she also held the opinion that women shouldn’t have to wear more than seven pounds of undergarments. She supported cycling and walking to promote a healthy and active life. But her ideas were also ridiculed by the popular press, and again only a small minority of women ever dared to venture into such revolutionary styles. Oscar and Constance Wilde were supporters of Lady Harberton’s ideas, and Wilde wrote of the ‘tyranny of tight lacing’.

Ideas around ‘hygenic dress’ circulated further. In 1884 the first Jaeger store opened, promoting the idea of wearing animal, rather than plant fibres next to the skin. Opened by Lewis Tomalin, the store – first called ‘Dr Jaeger’s Sanitary Woollen System’ – was inspired by the work of Dr Gustav Jaeger – a hygienist and naturalist who believed that wools were more breathable and healthy next to the skin than plant-based fabrics such as cotton. Wilde wrote about Dr Jaeger’s research, ‘on the sanitary values of different textures and colours he speaks of course with authority, and from a combination of the principles of science with the laws of art will come, I feel sure, the costume of the future’. The playwright George Bernard Shaw was also a fan of this approach.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Amber Butchart

Amber Butchart – is a fashion historian and author working across cultural heritage, broadcasting and academia, who specialises in the historical intersections between dress, politics and culture. Amber has researched and presented documentaries for the BBC, including the six-part series A Stitch in Time for BBC Four that fused biography, art and the history of fashion to explore the lives of historical figures through the clothes they wore. She is an Associate Lecturer at London College of Fashion, a former Research Fellow at the University of the Arts London. Her latest book, The Fashion Chronicles: Style Stories of History’s Best Dressed, is out now.