Perceptions of childhood

In the mid-18th century, childhood began to be viewed in a positive light, as a state of freedom and innocence. Professor Kimberley Reynolds explores how this new approach influenced 18th and 19th-century writers, some of whom wished they could preserve childhood indefinitely.

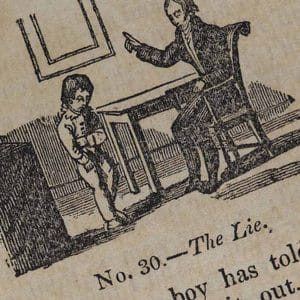

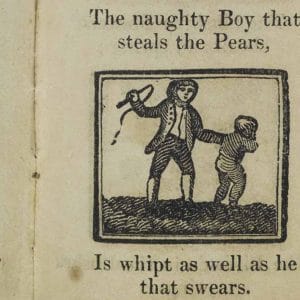

From around the middle of the 18th century, many people in Britain began to think about childhood in new ways. Previously, the Puritan belief that humans are born sinful as a consequence of mankind’s ‘Fall’ had led to the widespread notion that childhood was a perilous period. As a result, much of the earliest children’s literature is concerned with saving children’s souls through instruction and by providing role models for their behaviour. This religious way of thinking about childhood had become less influential by the mid-18th century; in fact, childhood came to be associated with a set of positive meanings and attributes, notably innocence, freedom, creativity, emotion, spontaneity and, perhaps most importantly for those charged with raising and educating children, malleability.

Central to the change in how childhood was understood was the work of the philosopher, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose Émile, or On Education (1762) not only rejects the doctrine of Original Sin, but maintains that children are innately innocent, only becoming corrupted through experience of the world. Émile is an invented account of an experiment in raising a boy using Rousseau’s method. Instead of the heavy-handed instruction of earlier periods, Émile is allowed to develop naturally: in nature and following his own, naturally healthy instincts. This method, the philosopher concludes, preserves the special attributes of childhood, resulting in well-adjusted adults who will also be good citizens. Rousseau’s ideas soon found their way into children’s literature, perhaps most obviously in his disciple Thomas Day’s popular Sandford and Merton (1783-89).

Constructing childhood

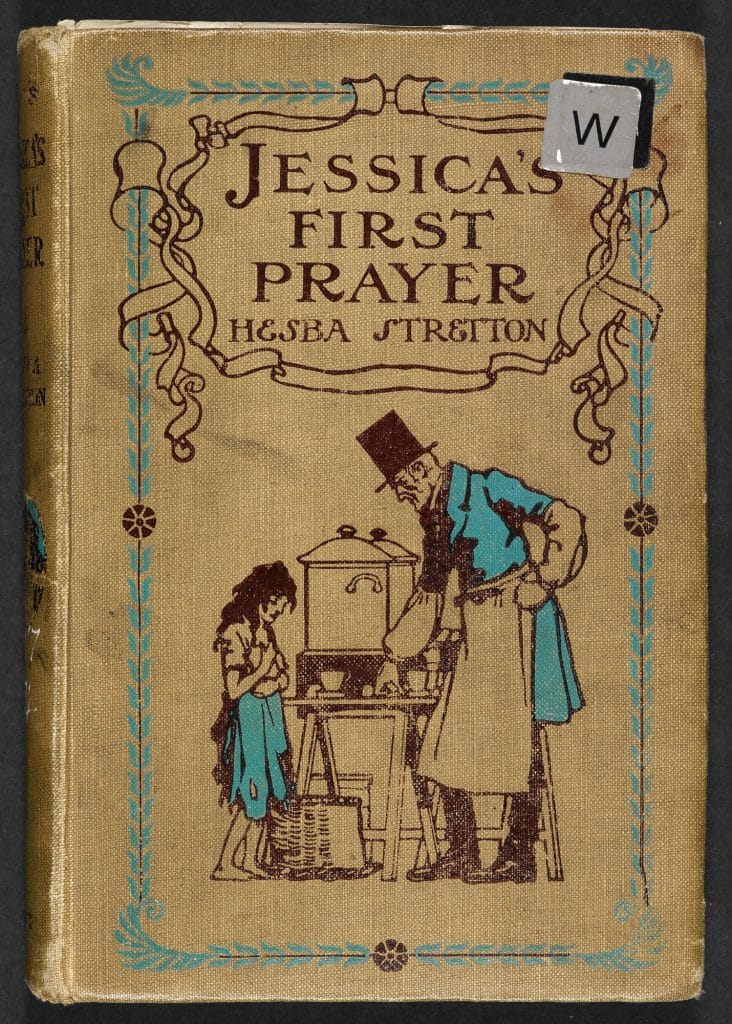

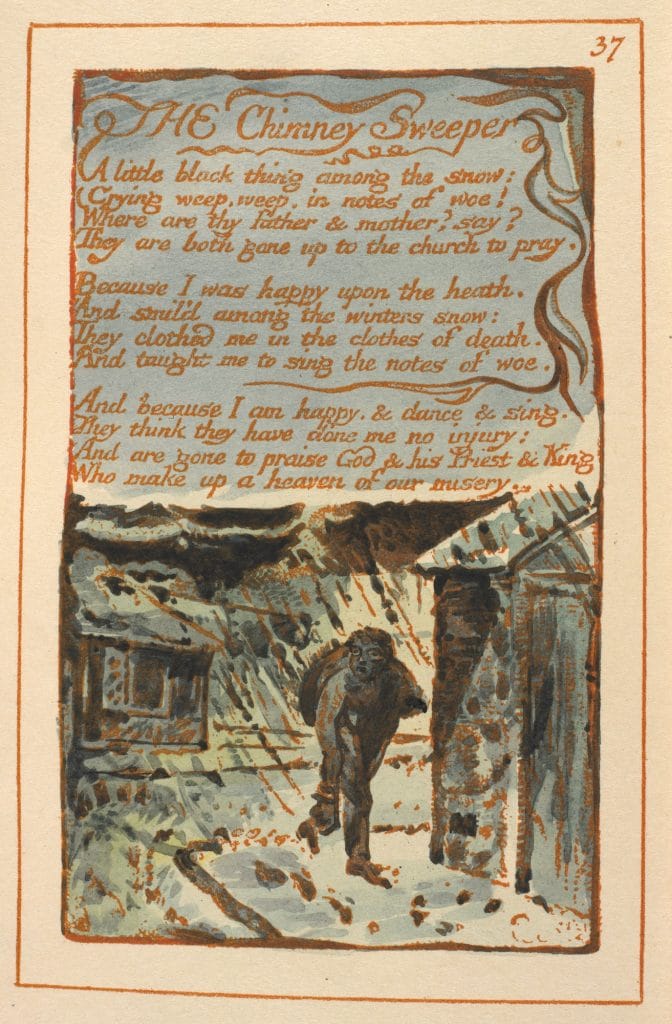

Following Rousseau, and in the hands of Romantic poets such as William Blake and William Wordsworth, childhood came to be seen as especially close to God and a force for good. In children’s literature, this idealised version of childhood became and remained enormously influential throughout the 19th and into the 20th century, though its Christian origins grew less pronounced. In children’s books (and other kinds of literature and art too) childhood innocence, goodness, frankness and vision regularly restore the moral wellbeing of adults and society. This is particularly obvious in 19th-century Evangelical tales about urchins in city slums who bring about the salvation of others. A typical example is Hesba Stretton’s Jessica’s First Prayer (1867), but the same motif is at work in less overtly religious works such as Frances Hodgson Burnett’s Little Lord Fauntleroy (1885), in which a young boy, raised in the poor part of an American city, effectively redeems and restores the antiquated and decaying British social structure.

That ways of thinking about and representing childhood could change so thoroughly over time shows that images and ideas about childhood are different from the actual lived experience of real children. Even when texts appear realistic, they will be underpinned by certain cultural understandings of childhood. Writers generally attempt to show their young readers what adults think children should be like. Usually these childhoods are rooted in middle-class life and values, with children of the poor either disappearing from view or being used as symbols and ciphers for literary and political ends. It should also be noted that many writers who idealised childhood were men, and so unlikely to be responsible for the day-to-day care of children, inevitably affecting how they viewed them.Just as there are many real childhoods at any given time, so multiple ideas or constructions of childhood co-exist in writing for children. In the 18th and 19th centuries, for example, not everyone subscribed to Rousseau’s theories about the nature of childhood. A few children’s writers such as Mary Martha Sherwood still held to the doctrine of original sin, while many saw childhood as the raw material from which adults were made rather than an ideal state to be valued and preserved.

Perpetual childhood

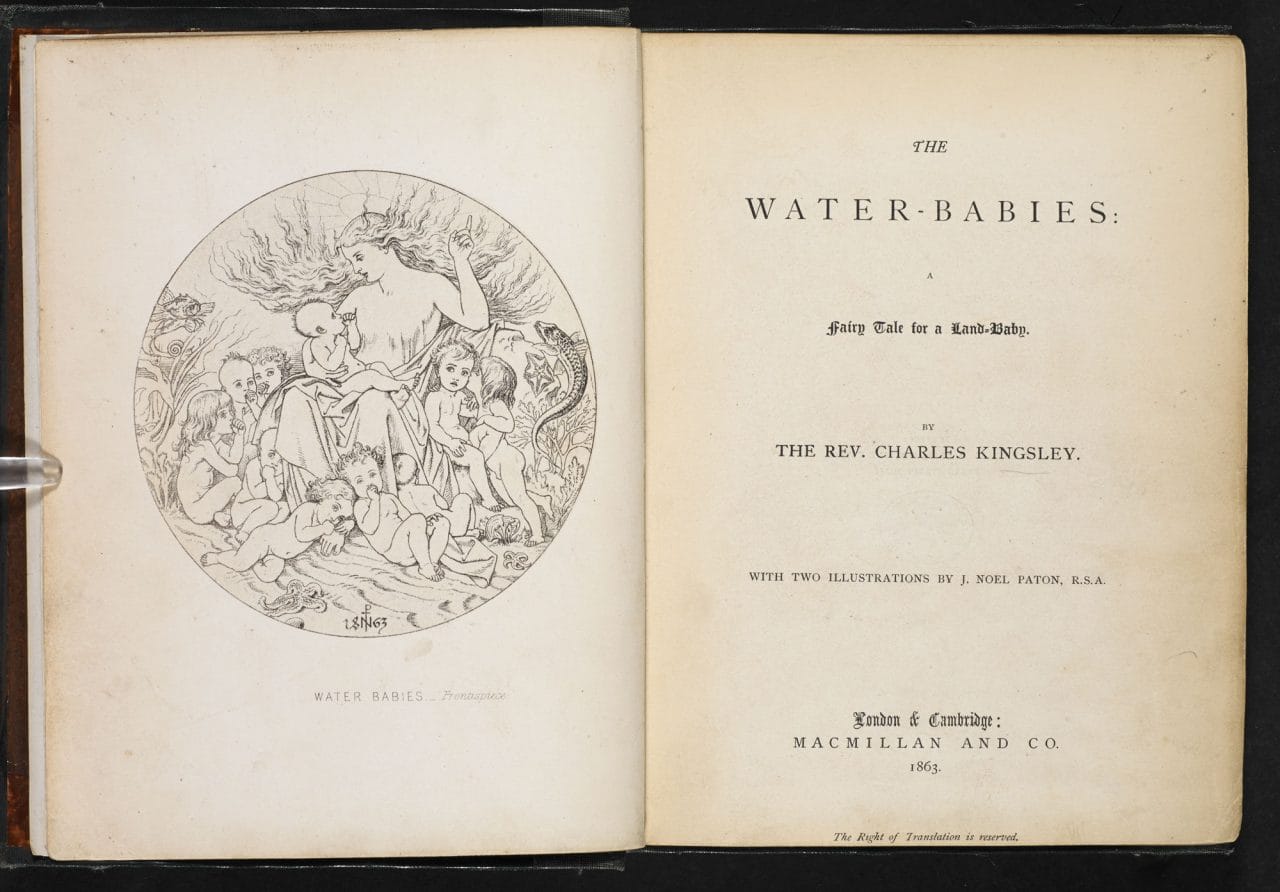

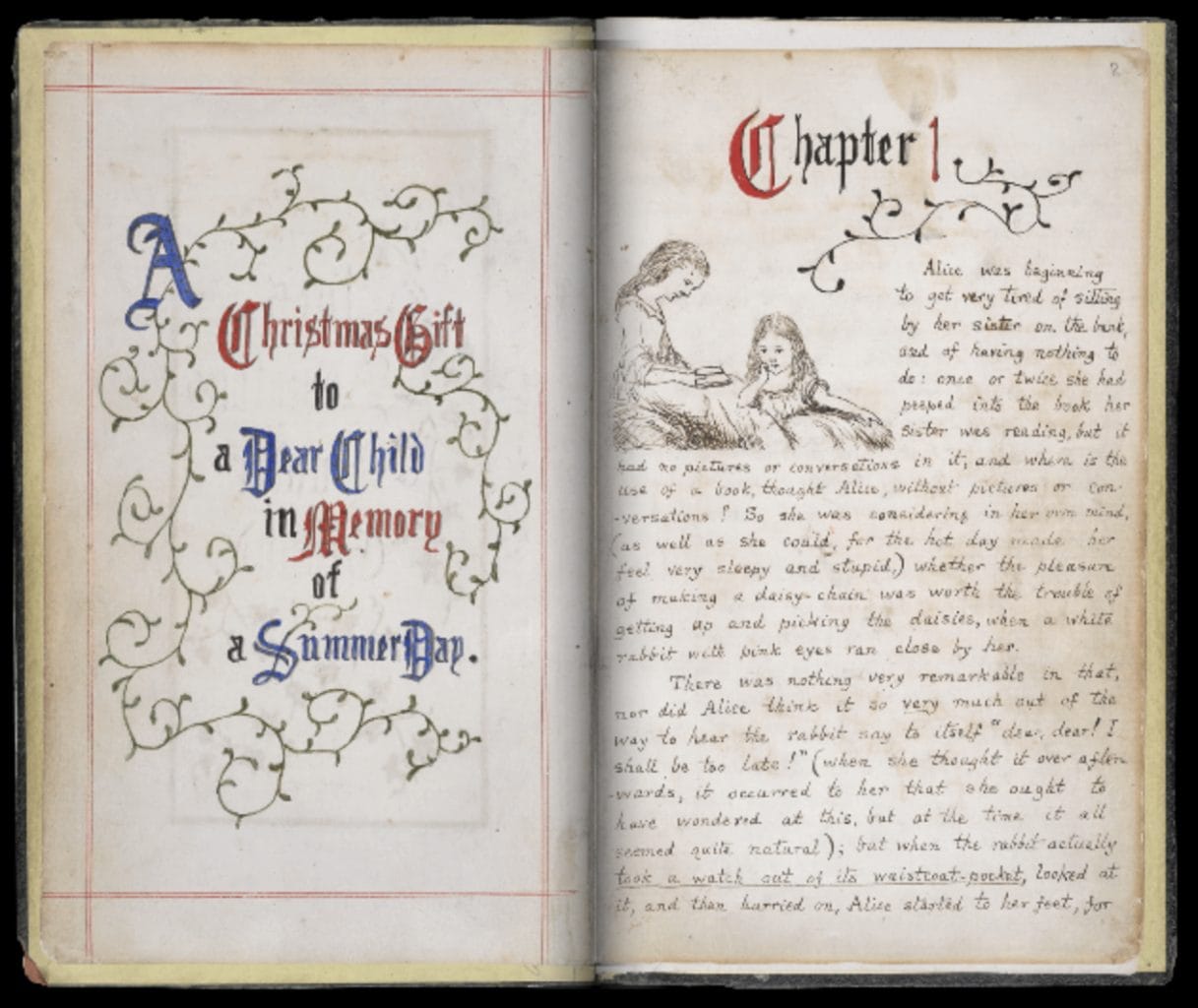

Some, however, did not see childhood as a state to be hurried through in order to achieve adulthood. The 19th century saw the development of what is sometimes called the Cult of Childhood, with adults exultantly celebrating childhood in texts and images. The connections with the Romantic ideal of childhood are clear, but many writers of the ‘Golden Age’ of children’s literature (beginning in the 1860s with Charles Kingsley’s The Water-Babies, 1863, and Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, 1865) went further, even expressing a longing themselves to be children once more. As Carroll put it in his poem ‘Solitude’,

I’d give all the wealth that years have piled,

the slow result of life’s decay,

To be once more a little child

for one bright summer day.

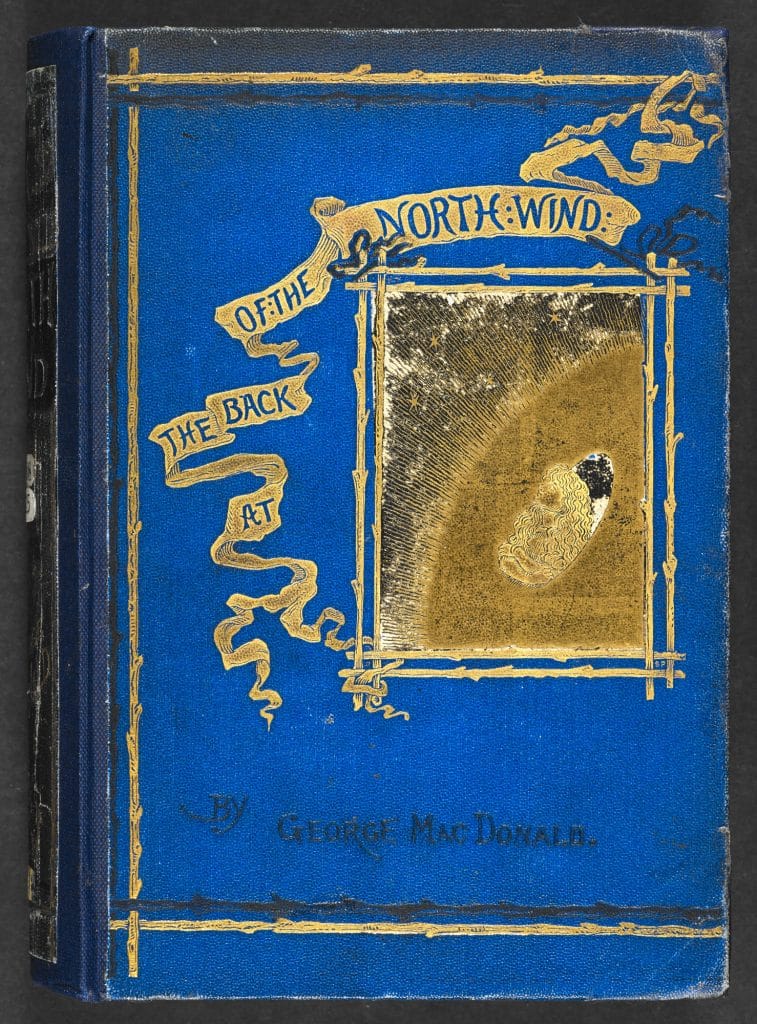

But perpetual childhood is impossible, and there is a notable tendency in some of the best-known Victorian fantasies for child characters to die in this world in order to be reborn (as in Kingsley’s Water-Babies) or to stay children forever elsewhere (George MacDonald’s At the Back of the North Wind, 1868). The Cult of Childhood persisted into the 20th century, reaching its height in J M Barrie’s Peter Pan (who first appeared in a play of 1904), who famously refused to grow up.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Kimberley Reynolds

Kimberley Reynolds is Professor of Children’s Literature in the School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics at Newcastle University. She has published widely on many aspects of children’s literature, most recently in the form of an audio book, Children’s Literature between the Covers (2011), Children’s Literature: A Very Short Introduction (2011), and as co-editor of Children’s Literature Studies: A Research Handbook (2011). With the support of a major Leverhulme Fellowship she is currently completing a study of Modernism, the Left, and Progressive Publishing for Children in Britain, 1910-1949.