Setting Shakespeare’s music – and the music of Shakespeare settings

Oliver Soden explores the challenges of creating operas based on Shakespeare’s plays.

‘There’s still a spot here!’

A planned opera of Twelfth Night defeated the Czech composer Bedřich Smetana. King Learwas pondered and then abandoned as a potential subject by both Giuseppe Verdi and Benjamin Britten. Antony and Cleopatra was Samuel Barber’s most infamous failure.

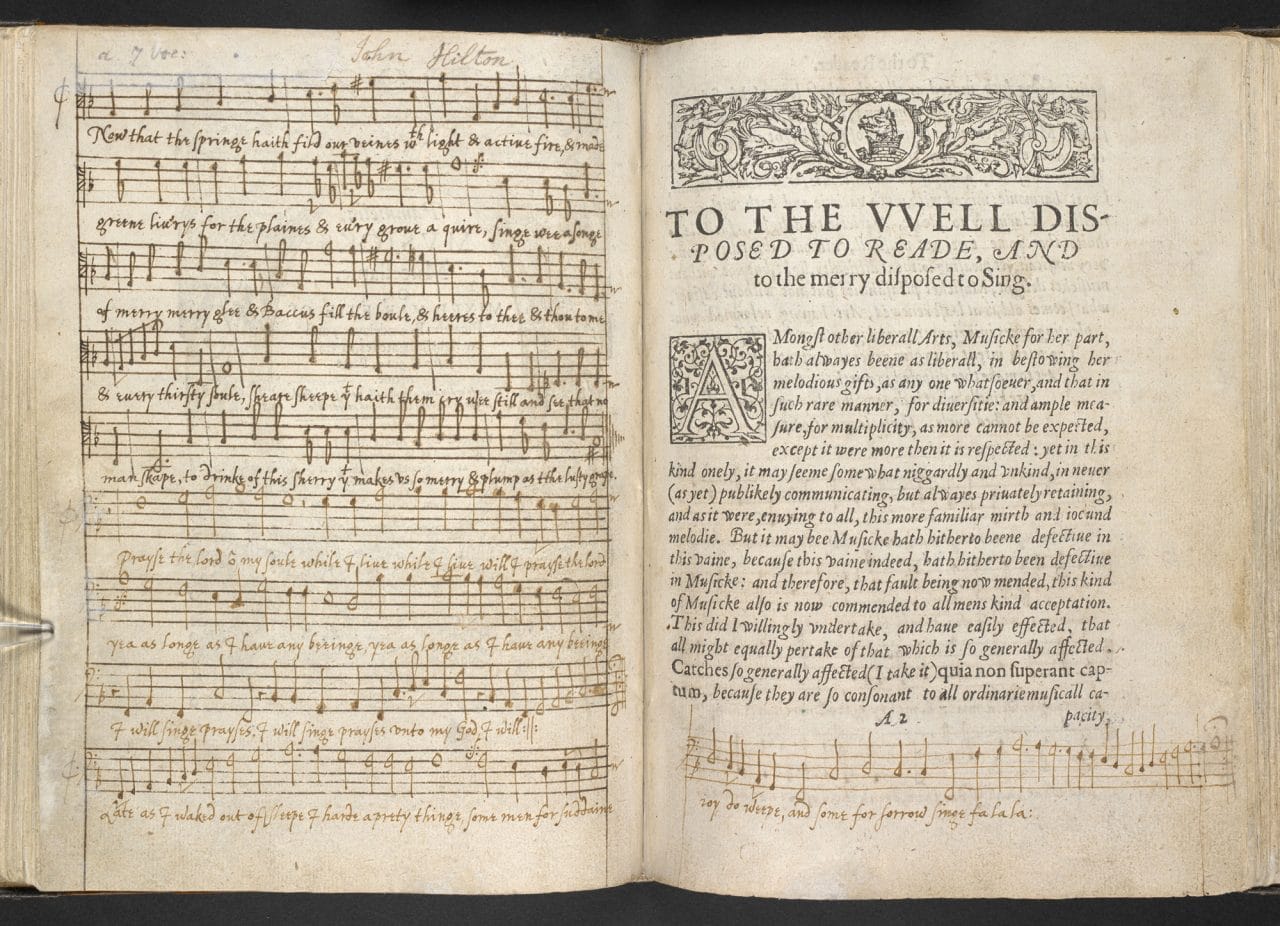

The prospect of setting Shakespeare’s plays to music is a rock on which several great composers have foundered. Shakespeare studded his plays with songs that have inspired composers from Schubert to Harrison Birtwistle, and his plots have been spun into immortal ballet scores without too much trouble. But the composer of a vocal work must put his own acoustic effects in the balance with Shakespeare’s, while avoiding mutually assured destruction. Some of Shakespeare’s most operatic characters have wandered out of their original plays and into successful operatic composites – witness Sir John Falstaff’s various appearances in works by Verdi (Falstaff), Gustav Holst (At the Boar’s Head) and Vaughan Williams (Sir John in Love). But it is rare for an opera of a play by Shakespeare not to send listeners back, howling, to the Collected Works in search of the playwright’s own music.

Verdi rules the roost for Shakespeare operas in the 19th century, and his librettists’ Italian adaptations of Othello, Macbeth and The Merry Wives of Windsor prevent constant comparison with the original. But even in a work such as Verdi’s Macbeth, which alongside Otello and Falstaff has taken on independent life, there can be the vertiginous sense of hearing Shakespeare through the wrong end of a telescope. A famous line such as Lady Macbeth’s ‘Out, damned spot!’ is translated by Francesco Piave as ‘Una macchia è qui tuttora!’, and in our English opera houses usually appears on the surtitles: ‘There’s still a spot here!’

But what of Shakespeare settings in the 20th century?

Benjamin Britten and A Midsummer Night’s Dream

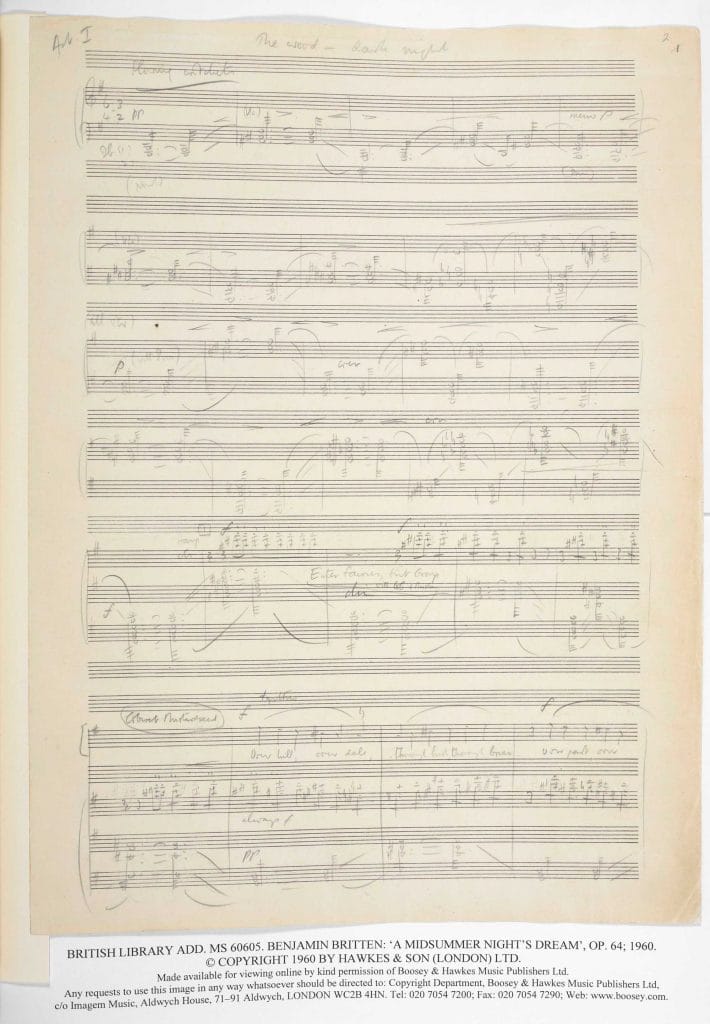

In terms of canonical status, Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1960) immortalised by a magical and evergreen production at Glyndebourne Festival Opera in Sussex, has entered the repertoire as an unquestioned masterpiece.

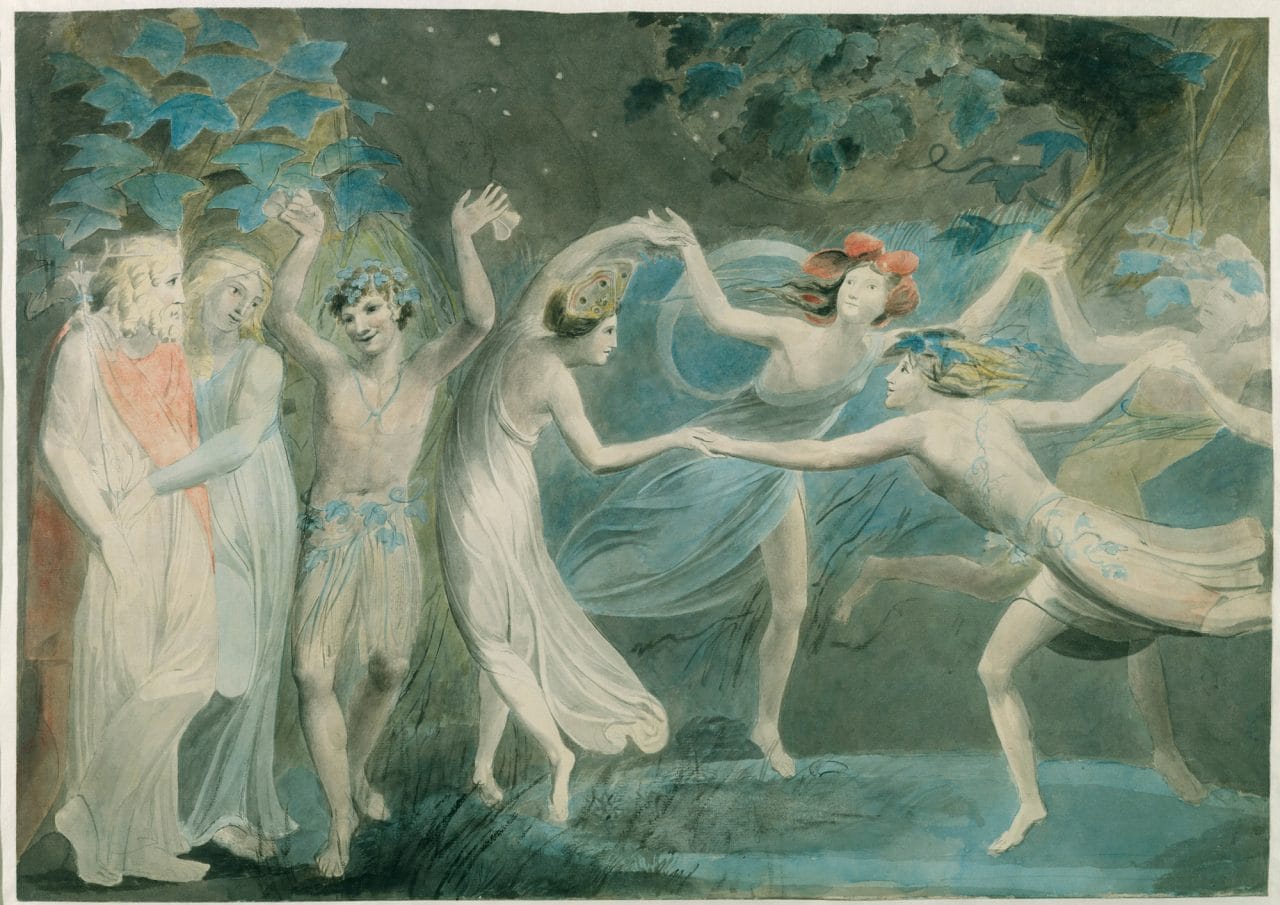

Pressured by ill-health, Britten managed with superhuman speed to create an often magical score, recognising the three distinct worlds of Shakespeare’s play – fairy, human, rude-mechanical – and responding with three memorably discrete aural worlds. The lovers’ music requires the most ardent performers to achieve lift-off, but the fairy wood and its inhabitants, once heard, are etched indelibly on the memory. Britten can paint ravishing scenic backdrops: twinkling percussive starlight ceding to a violin sunrise; orchestral undergrowth of queasily soughing strings.

Benjamin Britten, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, performed by the London Symphony Orchestra and conducted by Benjamin Britten (Decca, London) Act 1 Scene 1.

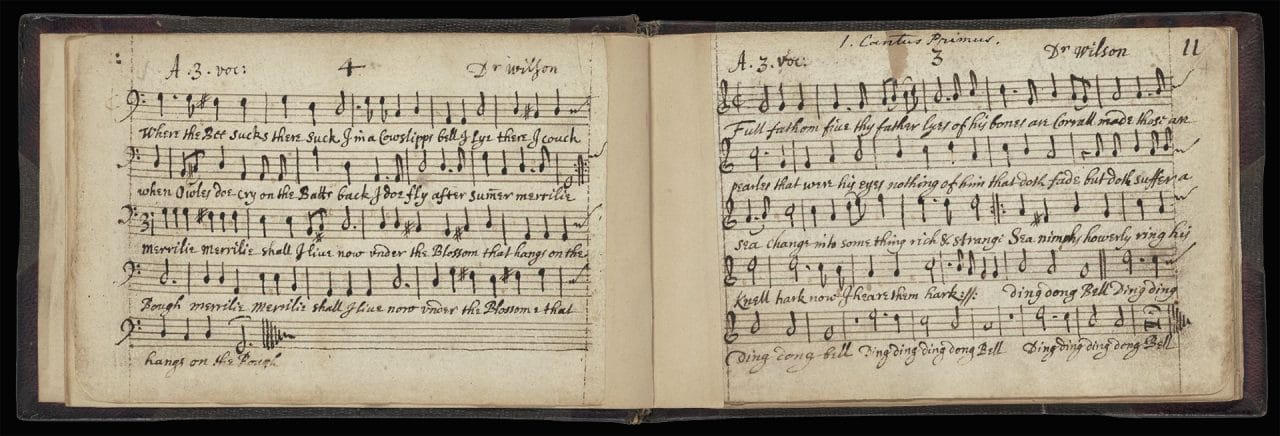

Fairy choruses of Britten’s beloved trebles combine with the other-worldly hoot of Oberon’s countertenor, or with the dizzy colaratura for the enchanted Tytania (the first syllable of her name changed to a longer vowel sound, more easily sung). Tearing through the enchanted wood is the more boisterous and brassy barbershop of the Rude Mechanicals, whose disastrous performance of Pyramus and Thisbe produced from Britten one of the most sustainedly hilarious episodes of musical invention since Haydn, with cruelly accurate parodies of composers from Donizetti to Berg. Best of all is the setting of the fairies’ final blessing on the Athenian court, where the pulse of Britten’s music and of Shakespeare’s verse become one, led by courtly trochaic steps on the harpsichord.

Benjamin Britten, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, performed by the London Symphony Orchestra and conducted by Benjamin Britten (Decca, London) Act 3, ‘Now until the break of day…’

A point about Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream often ignored is that it has one of the most successful ‘Shakespeare librettos’ in opera. It was really through practicality, and the need for a celebratory opera to mark the opening of a refurbished concert hall for Britten’s annual music festival in Suffolk, that the libretto came to be written. There was no time to ponder or commission an original text, and adapting a beloved play was a speedier option. It is a masterly work of assemblage from the original. It distils but it does not dilute. With a sleight of hand that would distinguish many a playwright, Britten and his partner, the tenor Peter Pears, cut the play in half, managing to keep the story intact with the addition of only one non-original line: ‘compelling thee to marry with Demetrius’. (Actually, the libretto neglects to marry the lovers at the end, but a clear production will solve that problem.)

Tastes will always vary as to whether Britten’s writing for boys’ voices is charming or twee. The fairy trebles in A Midsummer Night’s Dream can be both, but Britten’s handling of the character of Puck, Oberon’s hobgoblin henchman, is a failure that nearly pulls the opera down with it. Like some juvenile Leporello to Oberon’s Don Giovanni, Puck skips about the opera assisting with machinations both kind and malevolent. After a visit to Sweden, where Britten was impressed with some child acrobats, he decided his operatic Puck should be a speaking part for a boy, who must shout the lines in notated rhythms, egged on by a tumbling trumpet and snare-drum.

Benjamin Britten, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, performed by the London Symphony Orchestra and conducted by Benjamin Britten (Decca, London) Act 1, ‘Through the forest I have gone…’

In the wrong hands the role can be fatally irritating, with a skilled performer more engaging (English Touring Opera once cleverly rid the part of its adolescent overtones by casting a world-weary elderly man). But where Britten fails is in reducing the myriad complexities of Shakespeare’s character to a concept on which the composer spins almost no variation. In the play, Puck’s verse can scamper as bawdily as it can dance beautifully, sometimes within the same scene (the earthly farce of ‘then slip I from her bum, down topples she’ is soon airborne: ‘And now they never meet in grove or green, / By fountain clear, or spangled starlight sheen…’). Britten tarnishes Puck’s quicksilver by forcing him to produce all his lines in the same way, and ignoring the verse line to which the music is so attentive elsewhere: the interjecting trumpet demands caesura where the verse requires enjambment, and nothing is gained by the discrepancy.

Michael Tippett’s solution

Perhaps it is foolish to compare play and opera so closely, or to be forever yearning after the effects of the script. Operas with plays as sources should be considered on their own terms – but some operas invite the comparison more than others. The composer setting Shakespeare always runs the risk that his or her opera will forever be compared to the original and found wanting; that it will forever be a play-set-to-music, rather than an opera in its own right. These are not problems that Britten, for all his remarkable success with A Midsummer Night’s Dream, ever truly solves, though his solutions are more effective than some. Flick through the 21st century’s operatic versions of Shakespeare, and one soon comes to Thomas Adès’s The Tempest, which chooses to set a play whose ‘noises, sounds, and sweet airs’ have attracted composers from Henry Purcell in the 17th century, to Michael Nyman in the twentieth. Adès’s solution was to work with a libretto, by the playwright Meredith Oakes, that pares down Shakespeare’s text into short, plain couplets intended to evoke the original. The result was closer to a SparkNotes study guide (‘Shakespeare made easy’). The original text was watered down rather than effectively reduced (‘Ariel that’s enough/ There’s no need to be rough’), and this did nothing to banish a yearning for the play. More successful was Frank Kermode’s selection of text from King Lear that made up the 24 short scenes of Alexander Goehr’s Promised End (2010). By refusing to title the opera after the play, Goehr appeared to lay his cards on the table: his was a musical response to Shakespeare’s text rather than a direct setting of it, that would focus on the central relationship between Lear and Gloucester and filter the play through an interest in the ritual of Japanese Noh drama. But, thought one reviewer, the opera ‘still leaves the problem of how to find an appropriate melodic idiom for Shakespeare’s poetry’, making it ‘near impossible for anyone lacking knowledge of the original play to follow the psychological development’.[1] Like Hector Berlioz’s Béatrice et Bénédict (1862) before it, the effect was of an opera that pondered intriguingly on its original, but couldn’t soar dramatically free of its own accord.

Five years after Britten premiered A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the UK’s other great 20th-century composer, Michael Tippett (whose archive is held by the British Library), embarked on his third opera, The Knot Garden. Tippett differed from Britten in feeling that operas should never feature a libretto by a playwright or a poet. Instead, he wrote his own texts, using pared-down phrases intended only to blossom fully when set to music from which the words should never be extricated. In this he hoped to avoid the sense that the musical setting would forever be at war with the music inherent in the poetry. The ideal in a libretto, he once wrote to Britten, was a text ‘which we are not aware of, so that we come out of the theatre and say later “I suppose there was a libretto”’.[2]

Such a reaction would be impossible in setting a play by Shakespeare, even when gutted and filleted. Yet Shakespeare obsessed Tippett throughout his life. In his first opera, The Midsummer Marriage (1955), he alluded constantly to Shakespeare’s Dream, and in writing The Knot Garden he anchored his libretto in The Tempest. The scenario was his own, a contemporary tempest of storms psychological, musical and meteorological. Seven characters populate a dream-world conjured into existence by the Prospero-like figure of Mangus, with other figures recreating Shakespeare’s prototypes: a young girl named Flora reminds us of Miranda; a gay couple (one of the first in opera) recreate Ariel and Caliban. In Act 3 the characters come together to perform The Tempest, their quoted lines from the play often spoken rather than sung.

The Knot Garden reflects on and uses The Tempest to come to its own conclusions, to collate its seven characters in a contemporary union of togetherness and forgiveness – the obsession of all Shakespeare’s late plays. The opera is put in dialogue with the play without presuming to set it. It is a variation on Shakespeare’s original theme. In this, has Tippett settled how to set Shakespeare?

Perhaps. Yet The Knot Garden has yet to reach the canonical status of Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which is one of the few operas since Verdi to have achieved a life independent of its Shakespearean original. And so we go on. At the time of writing The Winter’s Tale and Hamlet are the latest candidates for operatic treatment and doubtless they won’t be the last. Were the problem easily solved, perhaps composers wouldn’t be so irresistibly drawn (or fatally put off) by the prospect of composing musical responses to Shakespeare’s plays – which, after all, will always endure.

脚注

The text in the article is © Oliver Soden. It may not be reproduced without permission.

撰稿人: Oliver Soden

Oliver Soden was born in Bath and educated at Lancing College, West Sussex, and Clare College, Cambridge, where he took a double first in English. A literary assistant for two years to RSC founder-director John Barton, he edited an edition of Barton’s ten-play cycle Tantalus (Oberon Books, 2014), before becoming a researcher on BBC Radio 3’s long-running programme Private Passions. He has written for a variety of publications, including the Guardian, Gramophone, The Art Newspaper, and a number of leading academic journals. Oliver is a noted authority on the life and work of the composer Michael Tippett, on whom he has lectured and broadcast widely; he is writing the first book-length biography of Tippett, to be published, in 2019, by Weidenfeld and Nicolson.