Slums

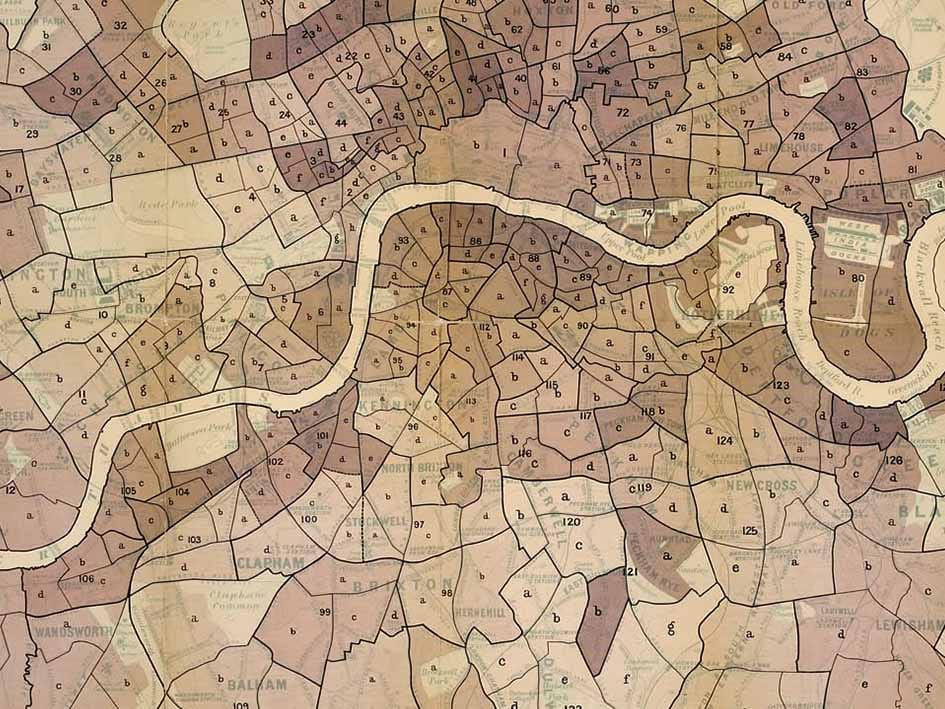

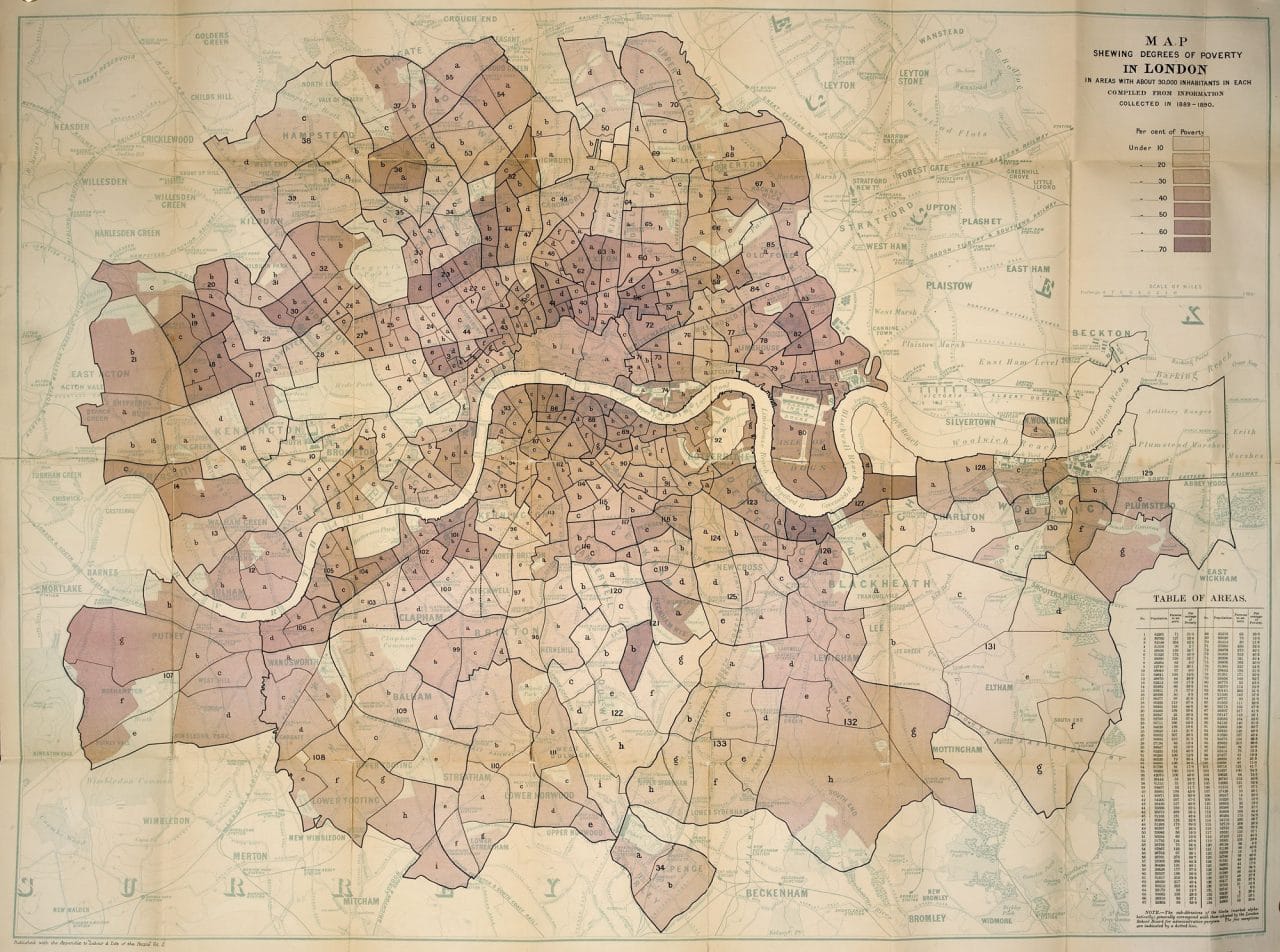

Judith Flanders examines the state of housing for the 19th-century urban poor, assessing the ‘improvements’ carried out in slum areas and the efforts of writers, including Charles Dickens and Henry Mayhew, to publicise such living conditions.

Between 1800 and 1850 the population of England doubled. At the same time, farming was giving way to factory labour: in 1801, 70 per cent of the population lived in the country; by the middle of the century only 50 per cent did. Cities swelled as people flocked from the countryside to find work. This was exacerbated by migration (especially from Ireland during the Famine years in the middle of the century). As a result, cities only big enough to contain 18th century populations were under pressure to house their new residents.

Previously, the rich and poor had lived in the same districts: the rich in the main streets; the poor in the service streets behind. Now, the prosperous moved out of town centres to the new suburbs, while much of the housing for the poor was demolished for commercial spaces, or to make way for the railway stations and lines that appeared from the 1840s. Property owners received compensation; renters did not: it was always cheaper to pay off the owners of a few tenements than the houses of many middle-class owners. Thus the homes of the poor were always the first to be destroyed.

‘Improvements’

The reshaping of the city was always referred to as making ‘improvements’. In 1826, when the process was just beginning, one book boasted that ‘Among the glories of this age, the historian will have to record the conversion of dirty alleys, dingy courts and squalid dens of misery…into stately streets…to palaces and mansions, to elegant private dwellings’.[1]

Yet few worried what was to happen to those whose houses – and neighbourhoods – vanished. These people could not afford to live in the nice new streets. Instead, they ended up just moving into other already crowded districts, which therefore became even worse – and even more expensive. Many couldn’t even afford that, and ended up instead moving endlessly from place to place, without a home.

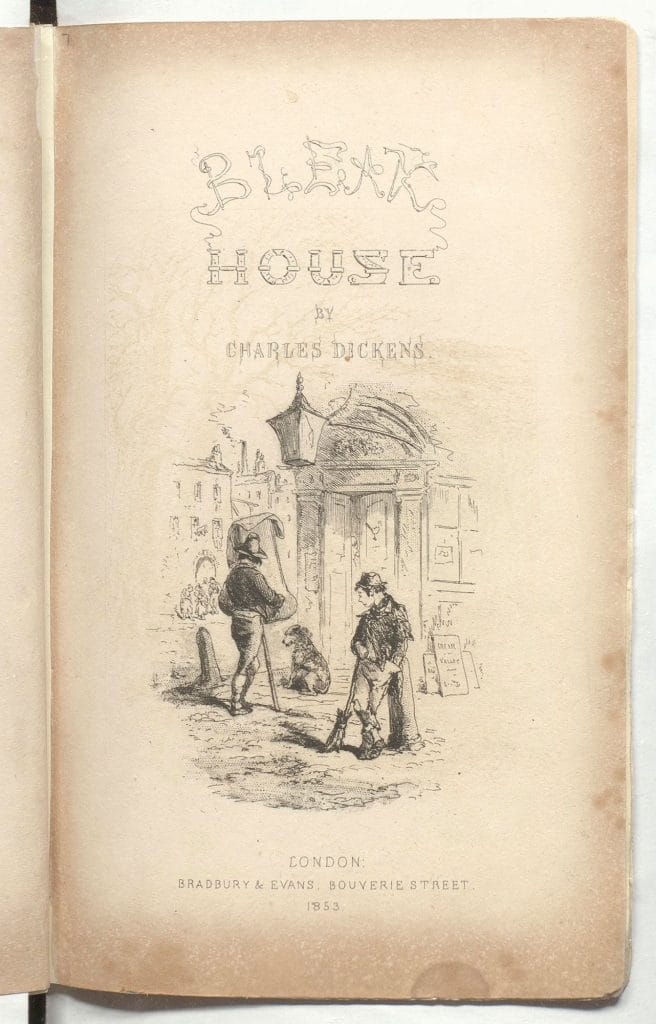

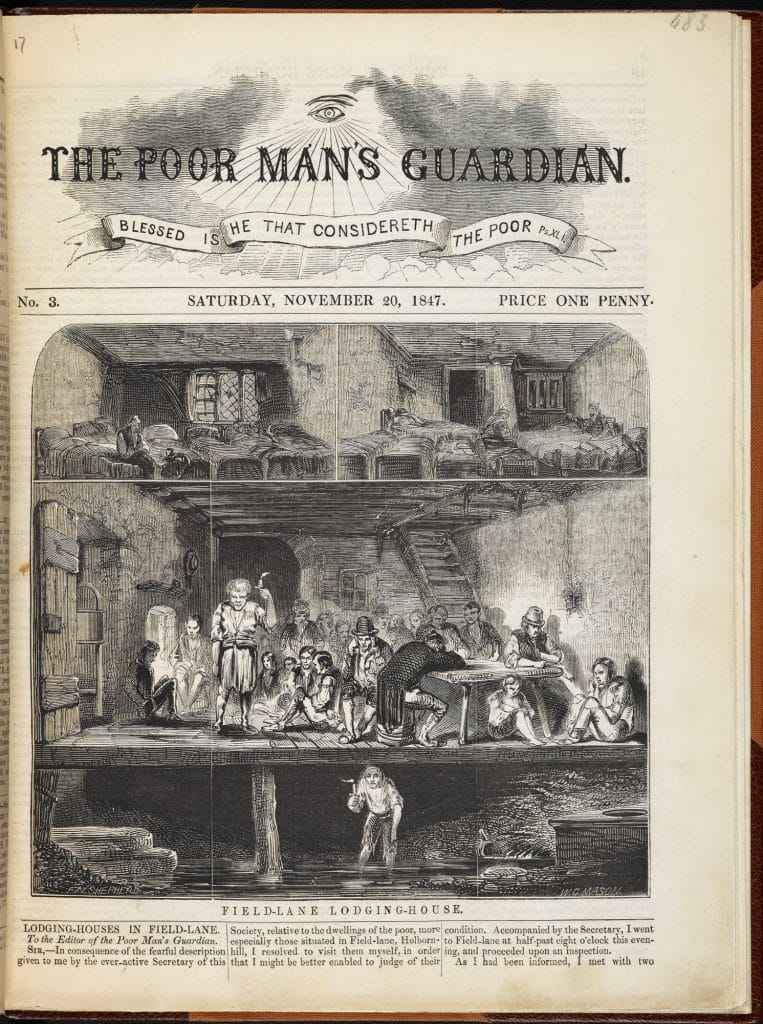

For the ‘improvers’, this was not a problem, since it was easier to think of the inhabitants of the slums as being, not hard-working but impoverished people, but only drunkards and thieves. Field Lane, in Clerkenwell, for example, was said to have been ‘occupied entirely by receivers of stolen goods, which…are openly spread out for sale’.[2] The police frequently excused their lack of oversight of the slums by saying they were too dangerous to enter, but Dickens, for one, knew better, and that insomniac author frequently walked these areas, learning about the other London: ‘I … mean to take a great, London, back-slums kind of walk tonight, seeking adventures in knight errant style’, he wrote to a friend. And the author Anthony Trollope’s younger brother claimed that, aged eight, he had wandered peacefully through the Clerkenwell slum, having heard the adults speak of its ‘wickedness’.[3]

‘Indescribable filth’

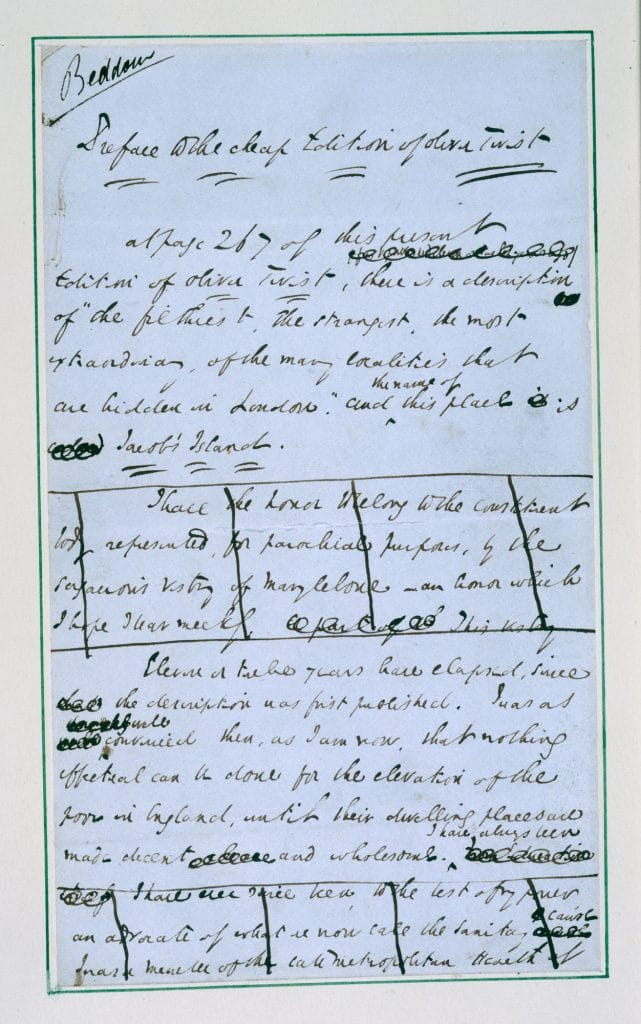

In 1838, Dickens described the horrible slum called Jacob’s Island, in south London. It was, he wrote, a place of ‘Crazy wooden galleries … with holes from which to look upon the slime beneath; windows, broken and patched … rooms so small, so filthy, so confined, that the air would seem too tainted even for the dirt and squalor which they shelter … dirt-besmeared walls and decaying foundations’. Although this description was in Oliver Twist (ch. 50), a work of fiction, journalist and campaigner for better housing, Henry Mayhew, described it in almost exactly the same way: ‘The water of the huge ditch in front of the houses is covered with a scum … and prismatic with grease … Along the banks are heaps of indescribable filth … the air has literally the smell of a graveyard.’”[4]

Much slum-housing was down narrow alleys, the passageways that had originally been designed to give access to stables. Built around dead-end courtyards, the houses therefore could have windows on just one side. Sometimes courts had even more buildings erected behind them, in what had been the yards of the houses behind; these buildings had no windows at all. In Bleak House, the orphaned 12-year-old Charley lives in a room with her baby brother and sister and, she notes with pride, ‘When it comes on dark, the lamps are lighted down in the court, and they show up here quite bright – almost quite bright’ (ch. 15). ‘Almost quite bright’ made their room not a slum at all, but ordinary working-people’s lodgings.Charley was, like many slum-dwellers, a hard worker. She and her siblings were only three in a room, but often a single room was home to a family of five or six, who might even take in ‘lodgers’, to share the cost. Different rooms in each house had different rents. The cheapest of all were the cellars, which at best were just damp and dark; in particularly bad lodgings, the liquids from the cesspools beneath seeped up through the floor.

Sanitation and disease

Sanitation was a pervasive problem. Few houses had drainage, and there were few privies. Usually an entire court, several hundred people, shared one standpipe – a single outdoor tap – for all their water supplies, and had one, or at most two, privies (toilets in a shed outside) for everyone.In 1849 a letter was published in the Times, giving a rare voice to the slum-dwellers themselves.

Sur, – May we beg and beseach your proteckshion and power, We are Sur, as it may be, livin in a Willderniss, so far as the rest of London knows anything of us, or as the rich and great people care about. We live in muck and filthe. We aint got no priviz, no dust bins, no drains, no water-splies, and no drain or suer in the hole place. The Suer Company, in Greek St., Soho Square, all great, rich and powerfool men, take no notice watsomedever of our cumplaints. The Stenche of a Gully-hole is disgustin. We all of us suffur, and numbers are ill, and if the Colera comes Lord help us.[5]

This was in St Giles, steps away from Tottenham Court Road, and written after the area had been ‘improved’ – in fact the courts’ single privy had been removed to make way for ‘improvements’.

When the Times followed up this letter, they found one room filled with the living and the dying side-by-side: a woman with cholera, two boys with fever, and their families. As Dickens addressed the authorities directly, after the homeless boy crossing-sweeper Jo dies in Bleak House of a similar fever: ‘Dead, your Majesty. Dead, my lords and gentlemen … Dead, men and women, born with heavenly compassion in your hearts. And dying thus around us every day.’

脚注

- James Elmes, Metropolitan Improvements (London: Jones & Co., etc., 1827), p. 2.

- Thomas Adolphus Trollope, What I Remember (London : Richard Bentley & Son, 1887), p. 11.

- Charles Dickens, ‘New Uncommercial Samples: On an Amateur Beat’, in The uncomercial traveller and other papers, 1859-1870, ed. by Michael Slater and John Drew, 4 vols (London: Dent, 2000), IV, pp. 377–385 (p. 380–381).

- Henry Mayhew, ‘Home is home, be it never so homely’, in Meliora: or, Better Times to Come, ed. by Viscount Ingestre (London: John W. Parker and Son, 1852), pp. 258–280 (pp. 276–7).

- The Times, 5 July 1849, p. 5.

The text in the article is © Judith Flanders. It may not be reproduced without permission.

撰稿人: Judith Flanders

Judith Flanders is a historian and author who focusses on the Victorian period. Her most recent book The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens’ London was published in 2012.