Sounds in The Waste Land: voices, rhythms, music

The Waste Land is crowded with voices and music, from ancient Hindu and Buddhist scripture to the popular songs of the 1920s. Katherine Mullin listens to the sounds of T S Eliot‘s poem.

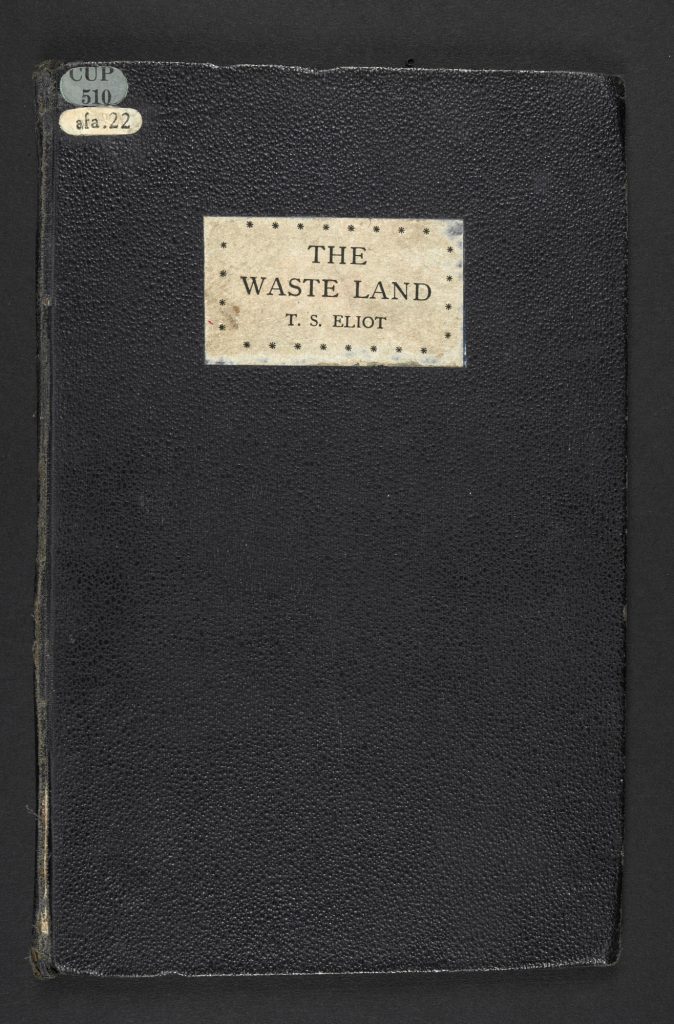

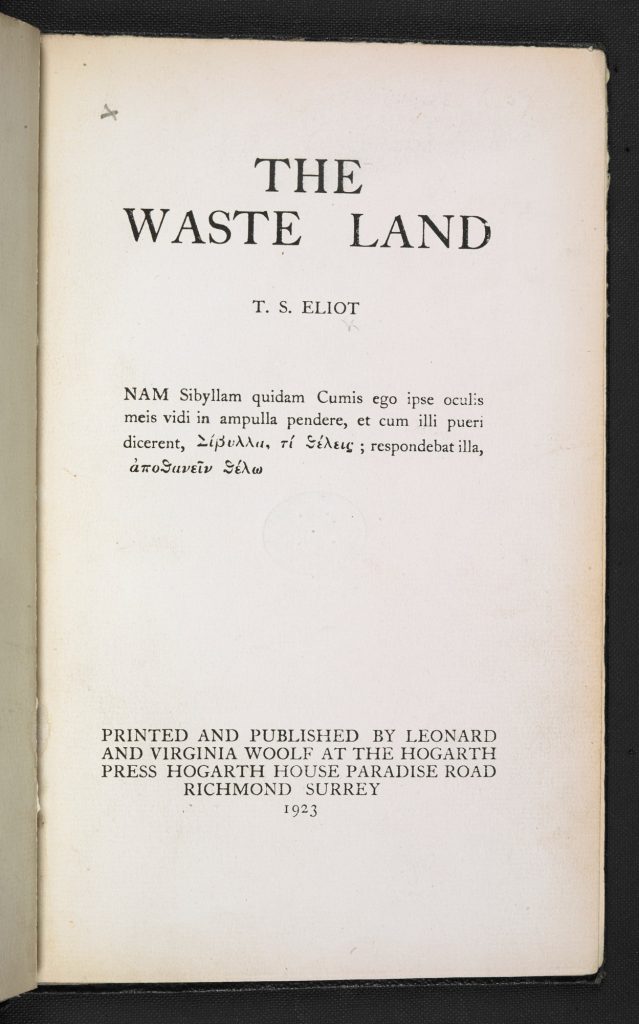

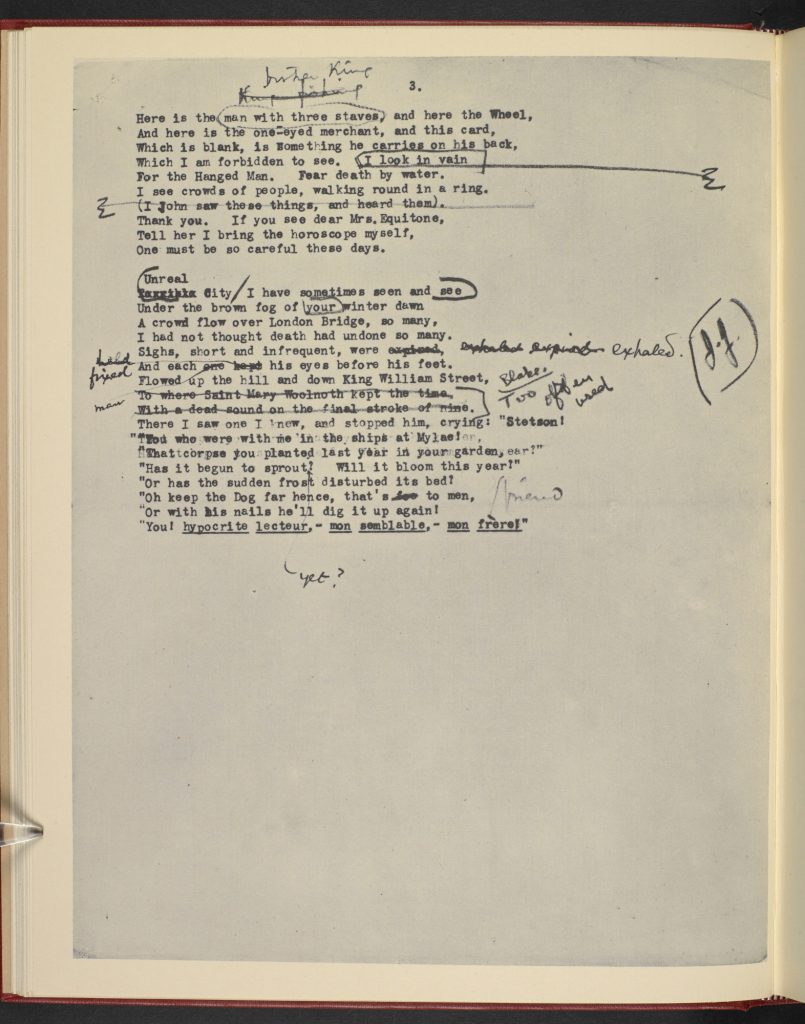

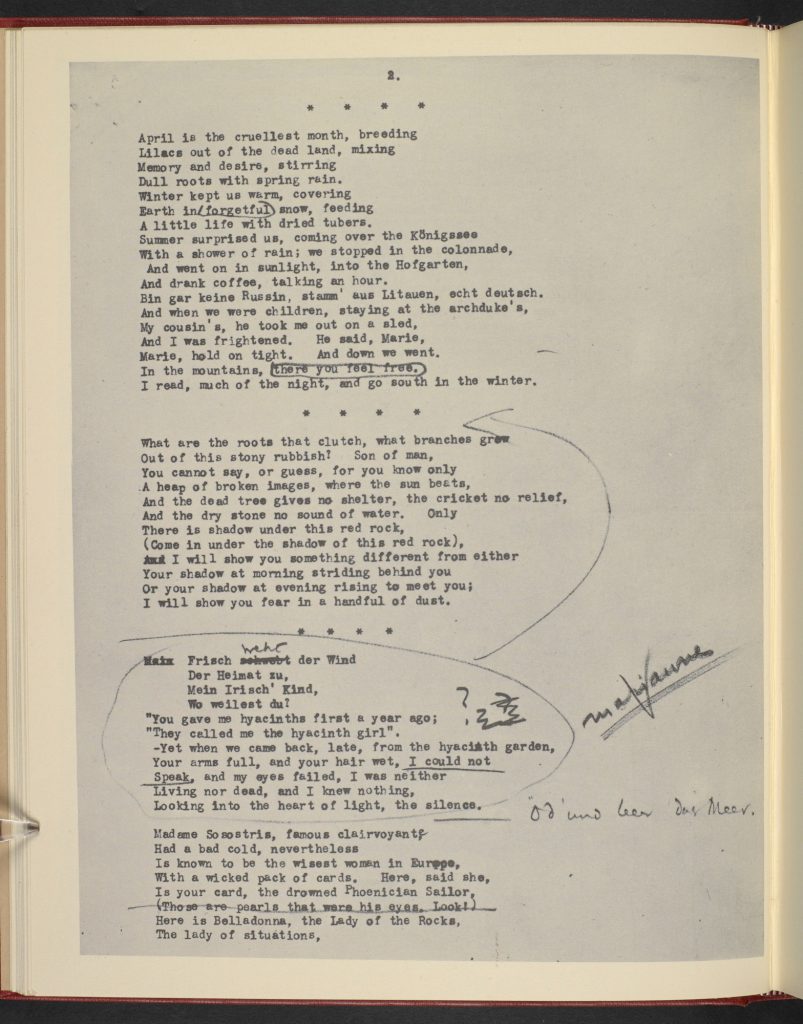

T S Eliot‘s The Waste Land (1922) is a noisy poem, packed with colliding sounds. It begins deceptively, with the quiet growth of ‘Lilacs out of the dead land’ (l. 2), the patter of ‘spring rain’ (l. 4), the silence of ‘forgetful snow’ (l. 6). Soon, stillness is shattered by talkative friends in the Hofgarten, chattering over coffee, then the excited, frightened voices of children sledging: ‘Marie, / Marie, hold on tight’ (ll. 15–16). Marie’s voice gives way to a register that could be the poet’s – ‘What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow / Out of this stony rubbish?’ (ll. 19–20) – before that speaker is interrupted by a snatch of song from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, the lament of a ‘hyacinth girl’ (l. 36), then ‘Madame Sosostris, famous clairvoyante’ (l. 43). Next, a ‘crowd flows over London bridge’ and ‘Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled’ (ll. 62, 64), until finally, Stetson’s mysterious interlocutor cuts in with his dark question about ‘That corpse you planted last year in your garden’ (l. 71). Voices compete, displacing one another, as if the listener is tuning an analogue radio.

A drama for voices

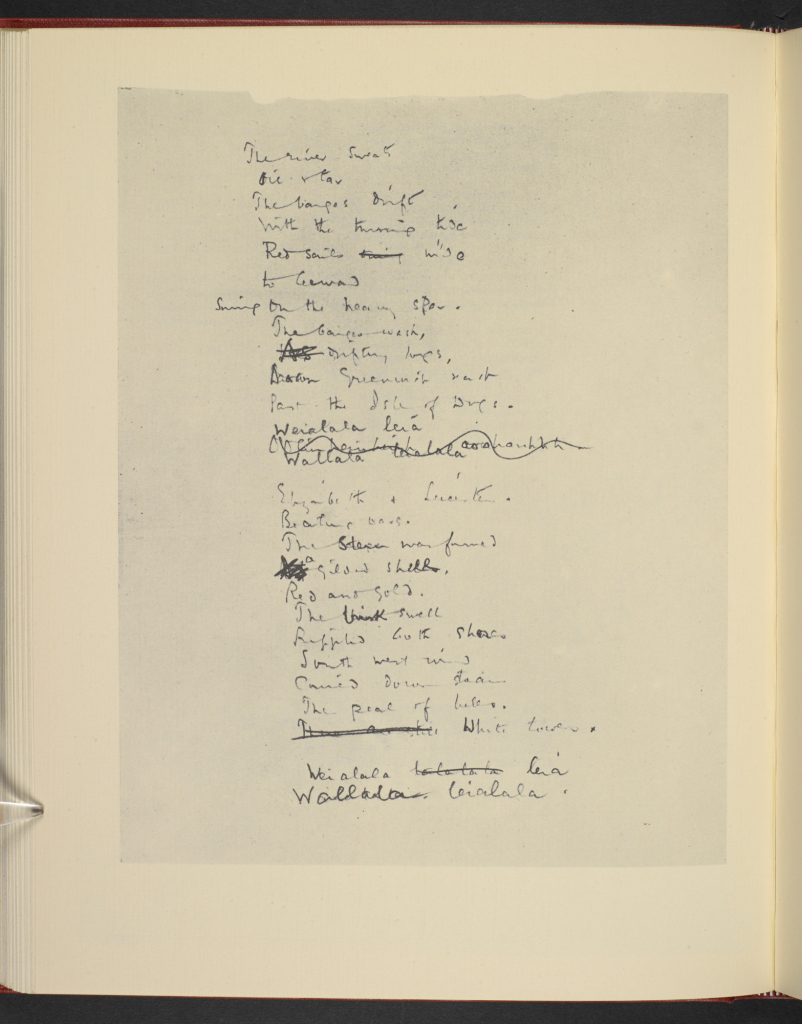

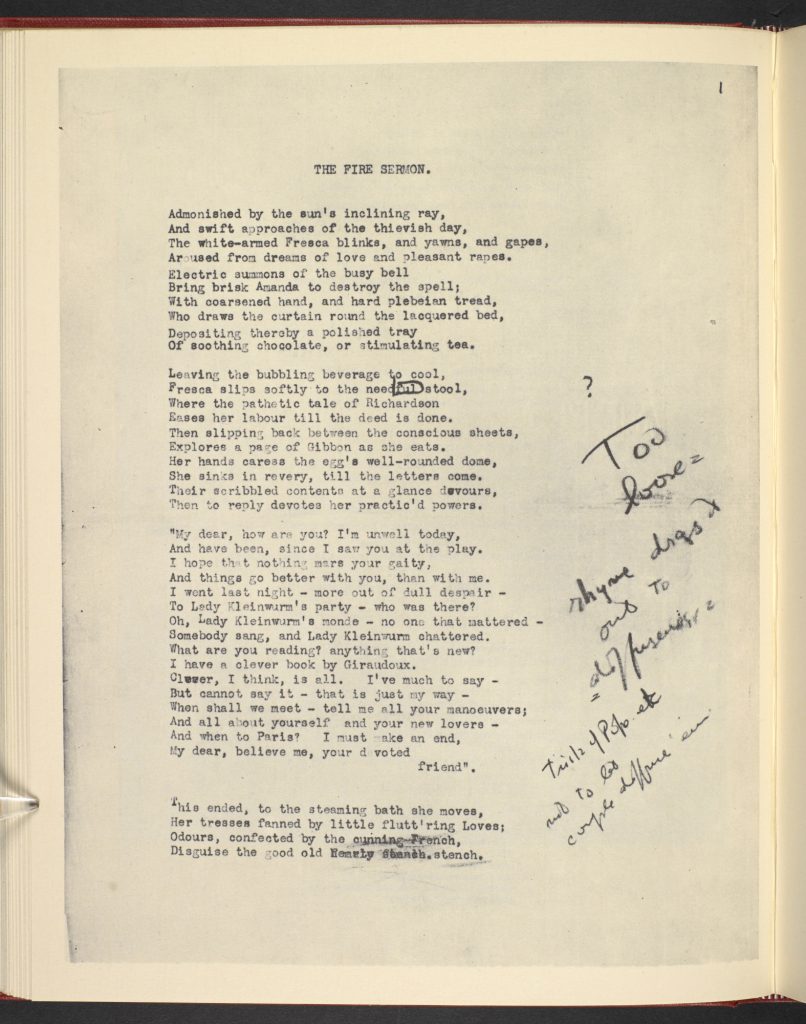

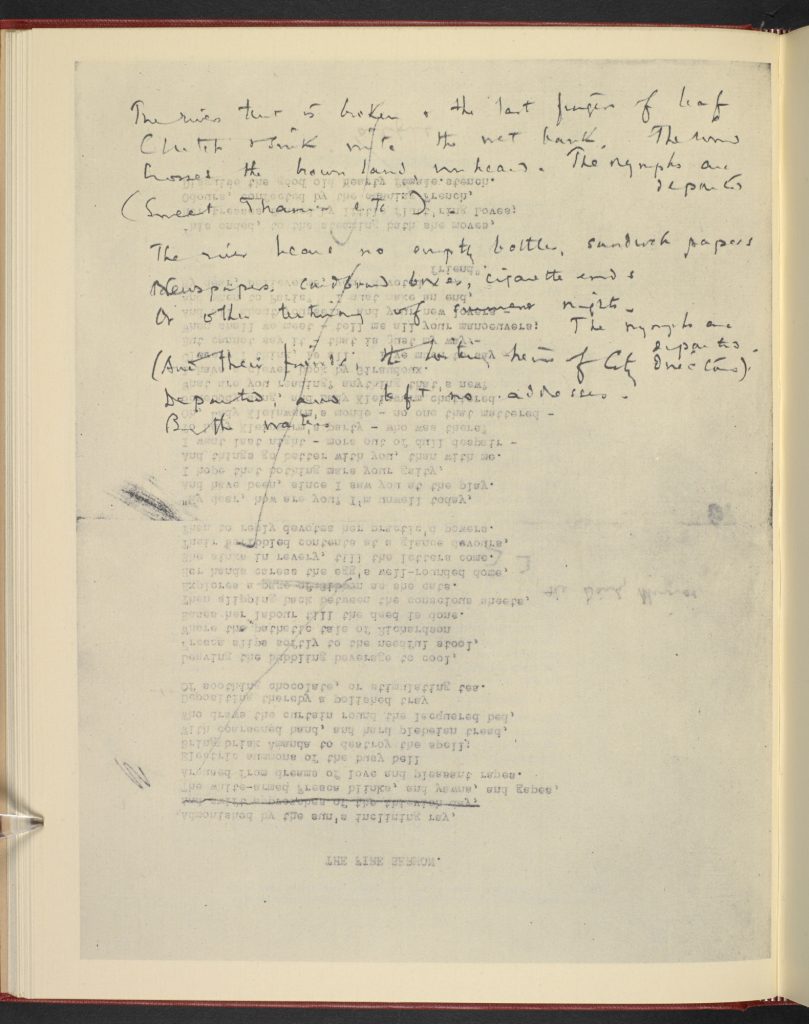

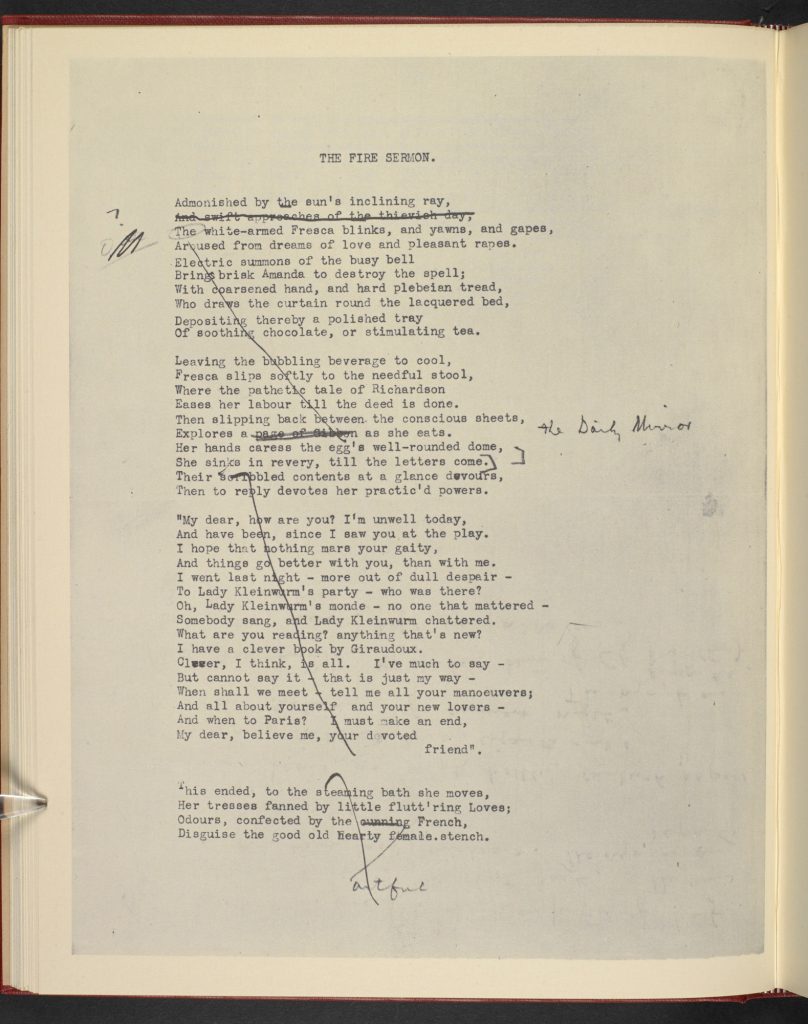

The poet Ted Hughes has described The Waste Land as ‘a drama for voices’, ‘an assemblage of human cries’, ‘exactly as in a musical composition, and only waiting for us to hear them’.[1] The snatch of Wagner interrupting ‘The Burial of the Dead’ – has somebody dropped a needle on a gramophone? – is only the most obvious sign. Musicality is evident in the rhythms of the poem’s language. ‘The Fire Sermon’, for example, begins ‘The river’s tent is broken: the last fingers of leaf / Clutch and sink into the wet bank’ (l. 174). However, Hughes observes more than the elegance of Eliot‘s characteristic cadences. Music, sound, song and voices are central to The Waste Land‘s idiom, its structure, and, above all, to its ambitions to record modernity.

Voices from the past

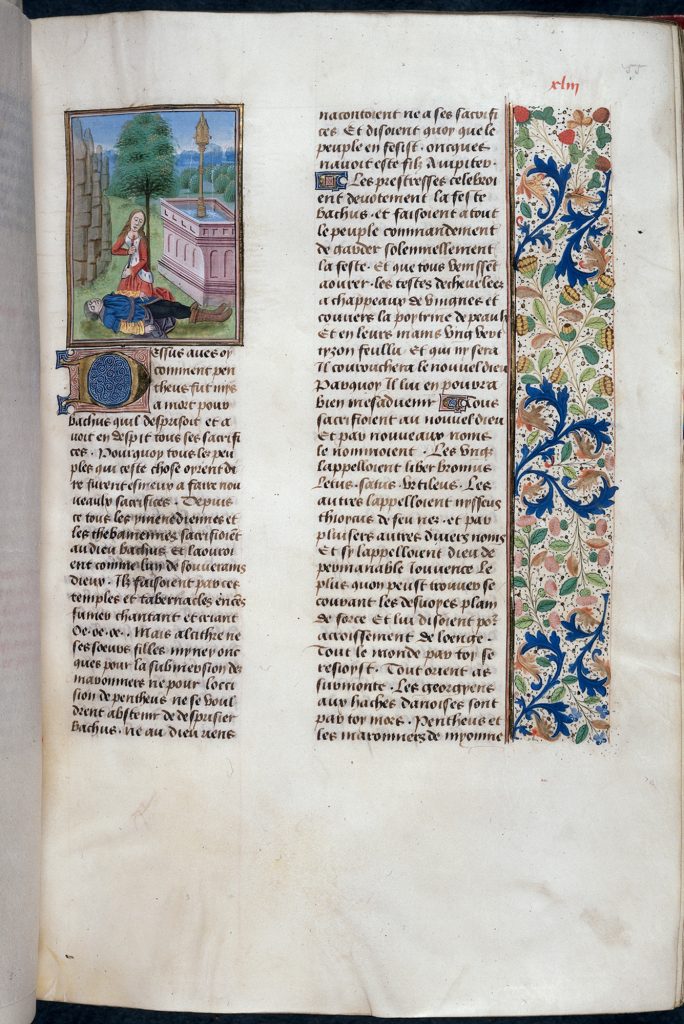

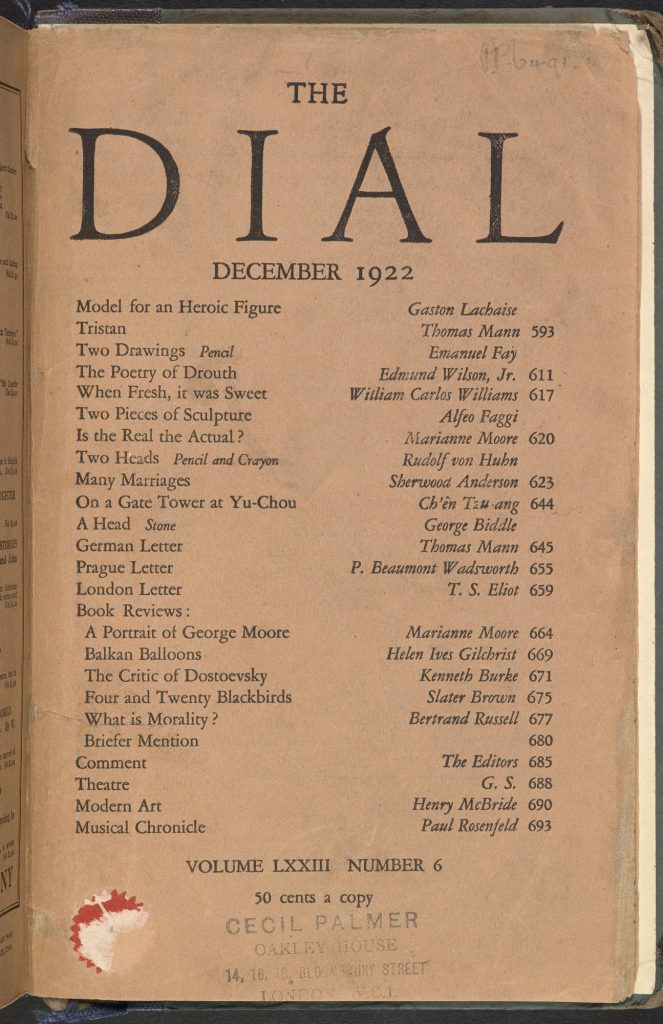

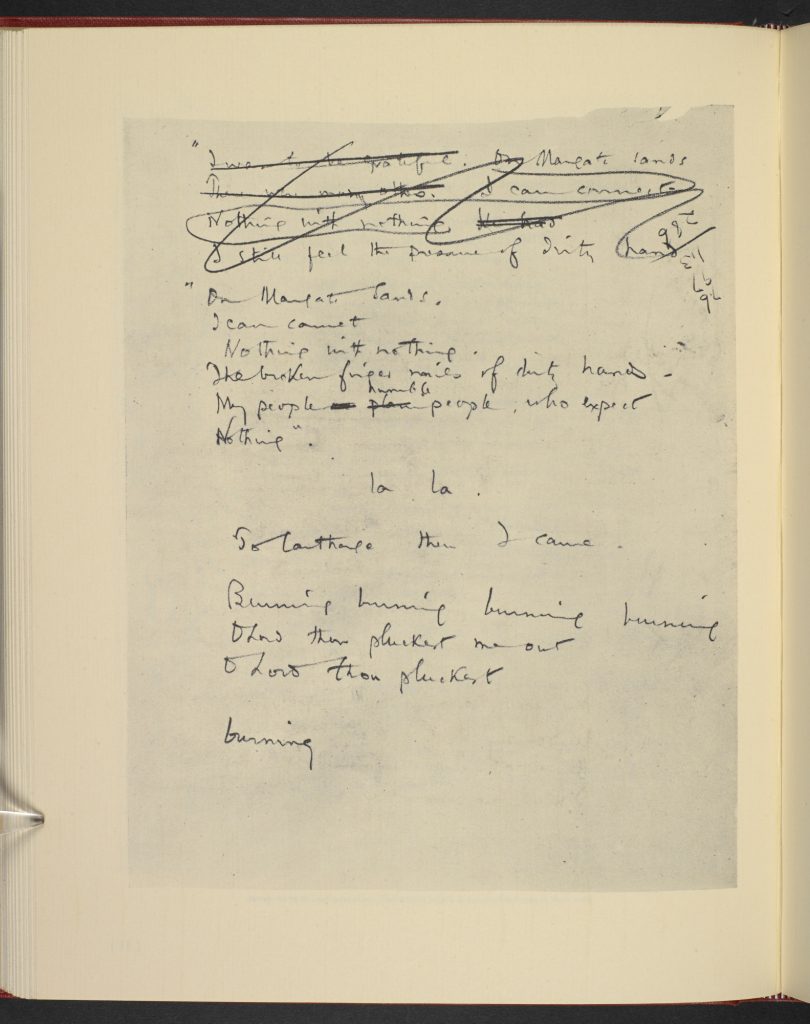

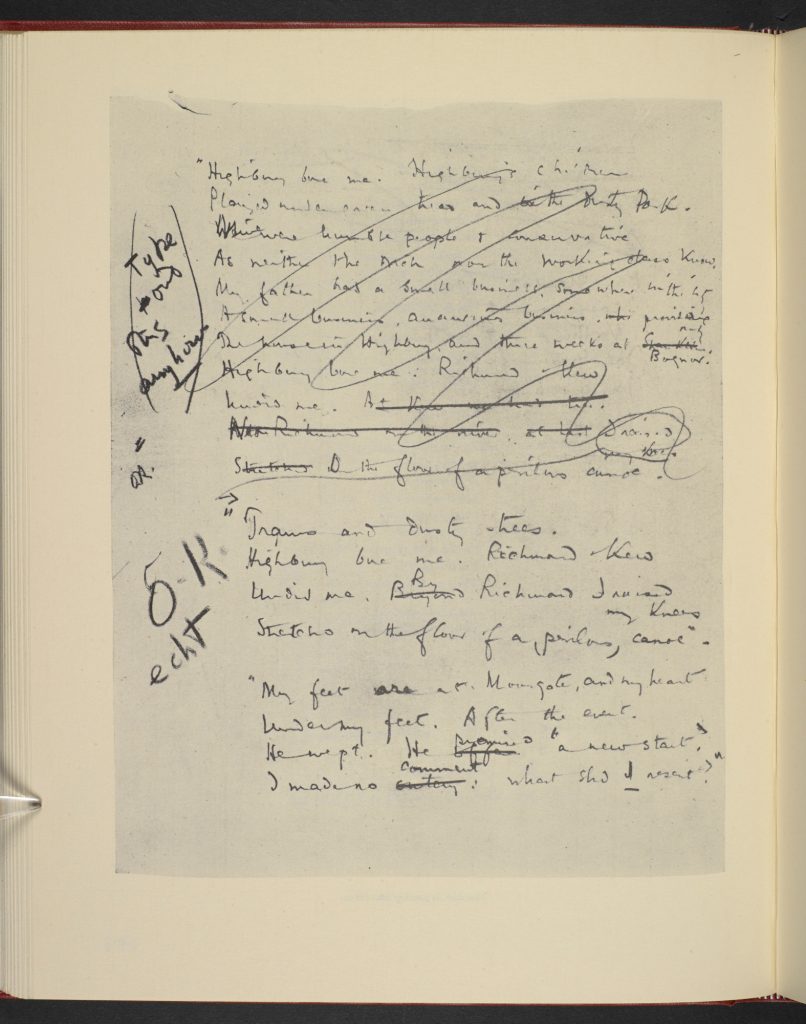

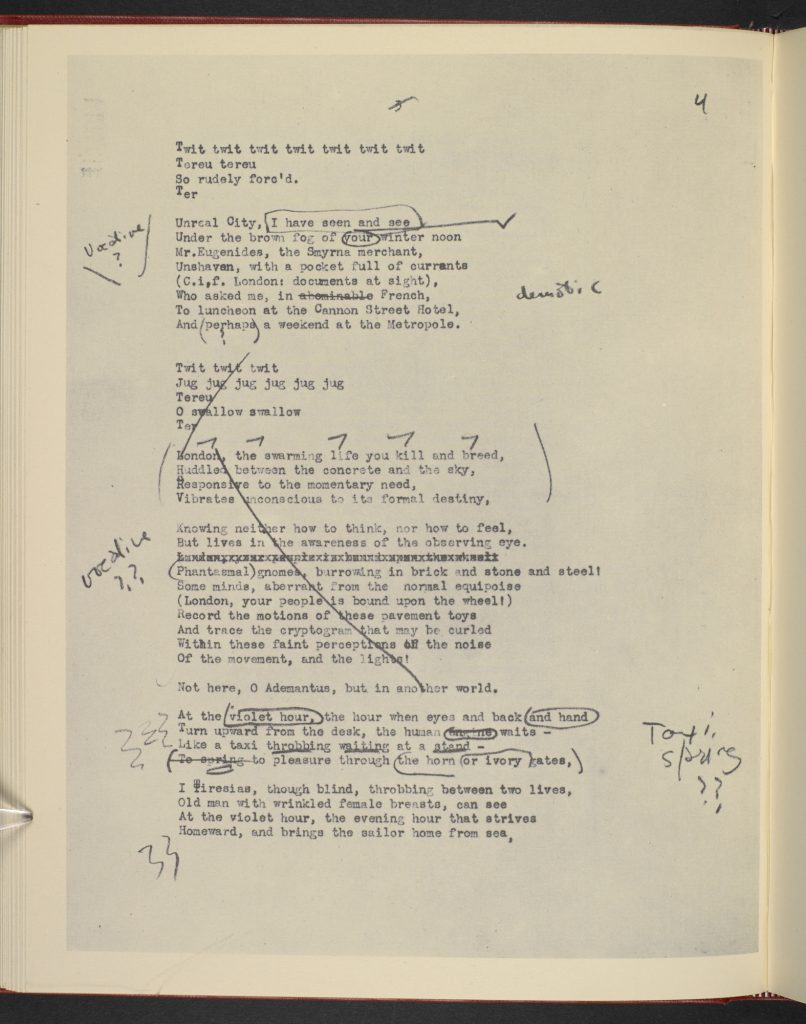

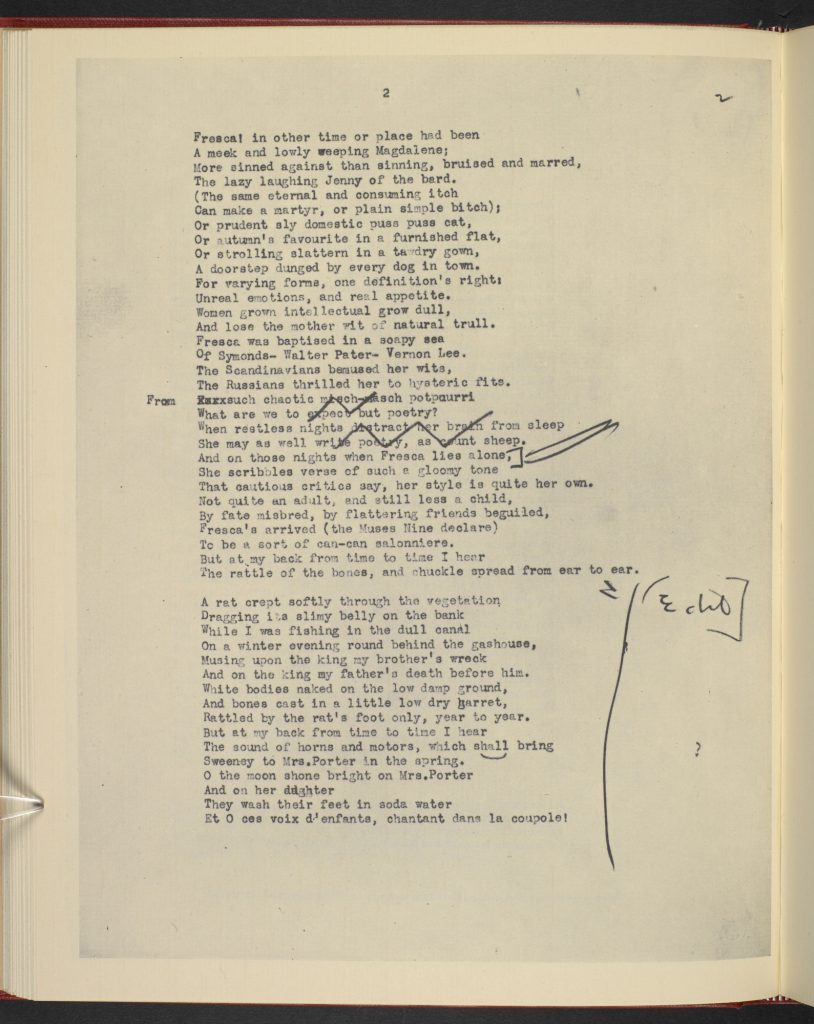

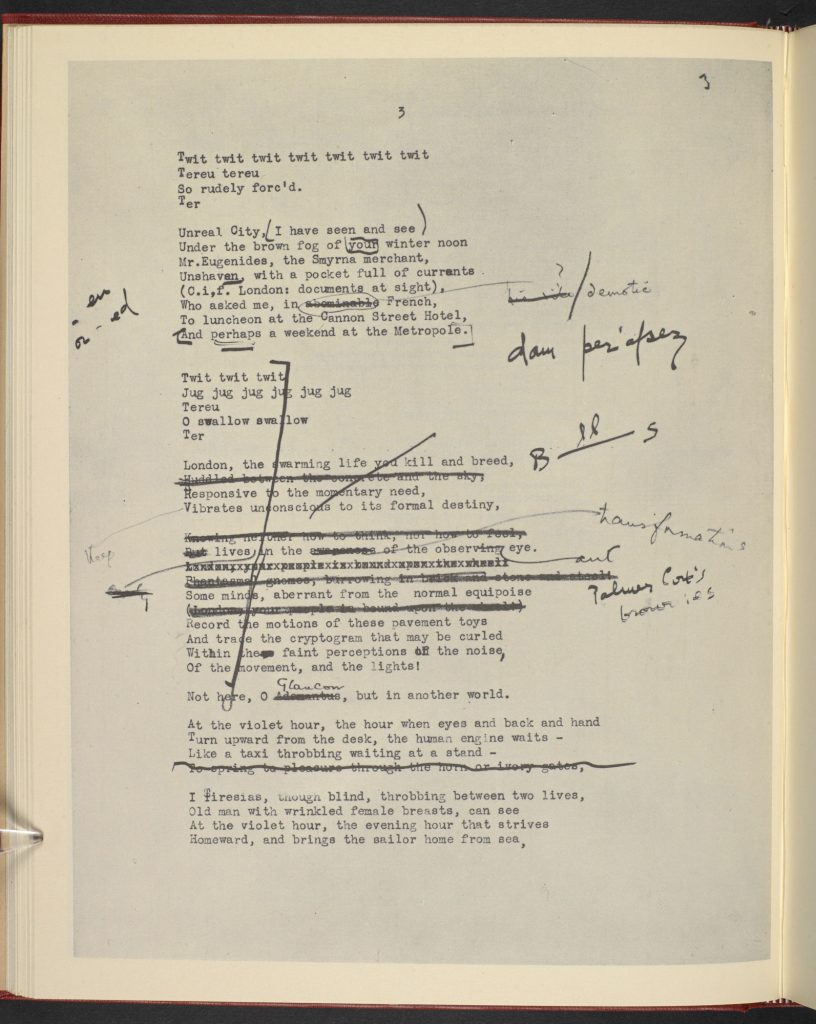

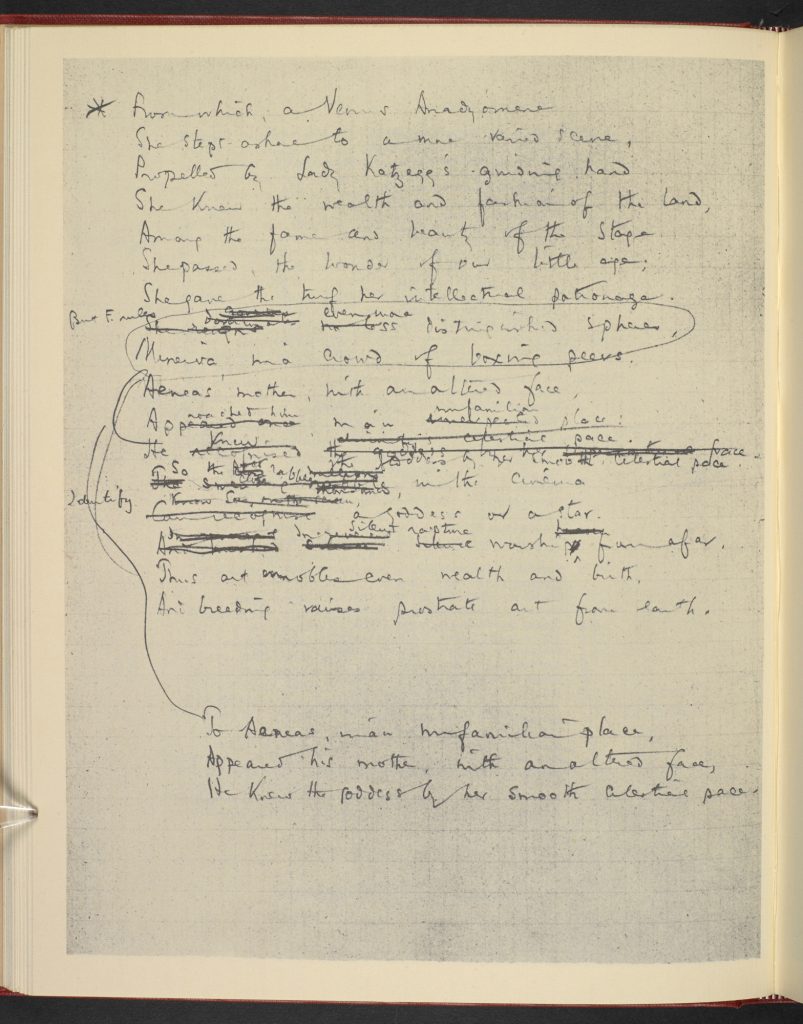

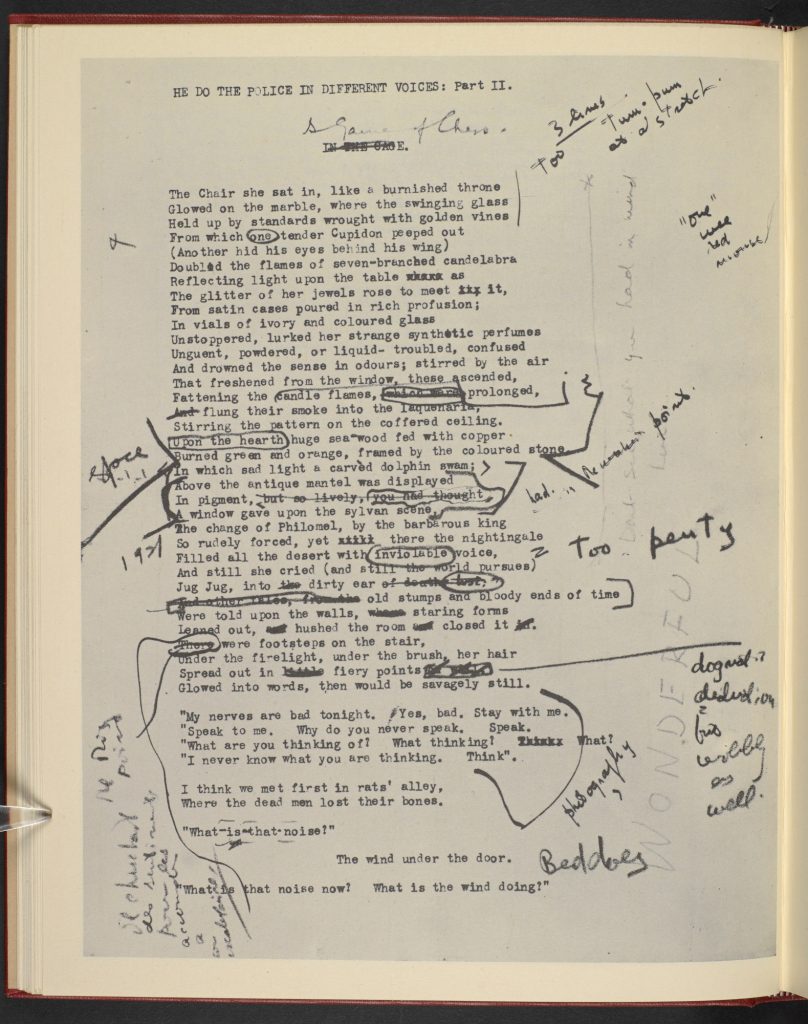

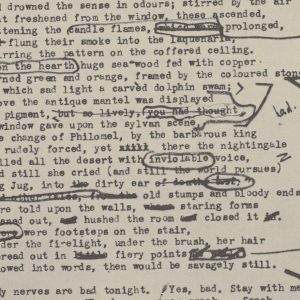

Composed in collaboration with Ezra Pound, The Waste Land is the paradigmatic example of Pound’s insistence that poets ‘make it new’. For Eliot, ‘newness’ involves the recuperation of a broken, shattered culture, and its reconfiguration for a post-war landscape: ‘these fragments I have shored against my ruins’ (l. 430). Tradition is acknowledged in the poem’s sounds. Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, composed in 1859 and premiered in 1865, looks back to Arthurian legend. Another myth offers a motif: the classical story of the rape of Philomela by her brother-in-law Tereus, who forces her silence by cutting out her tongue. In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Philomela is transformed into a nightingale, her song ‘Jug jug’, ‘Tereu’ (ll. 103, 206) a struggle to articulate her pain. Later, the nursery rhyme ‘London Bridge is falling down falling down falling down’ (l. 426), first published around 1744 but probably dating back to the Middle Ages, heralds the close of the poem with words from another tradition. The words spoken by the thunder, ‘Datta. Dayadhvam. Damyata. / Shantih shantih shantih‘ (ll. 432–33) – loosely translated as ‘Give. Compassion. Control’ and ‘The peace which passes understanding’ – are taken from the ancient Hindu and Buddhist scripture Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, composed before the middle of the first millennium BCE.

But these voices from the past, echoing throughout, are overwritten by other music belonging to the present and the future.

Popular music and the rhythms of the new

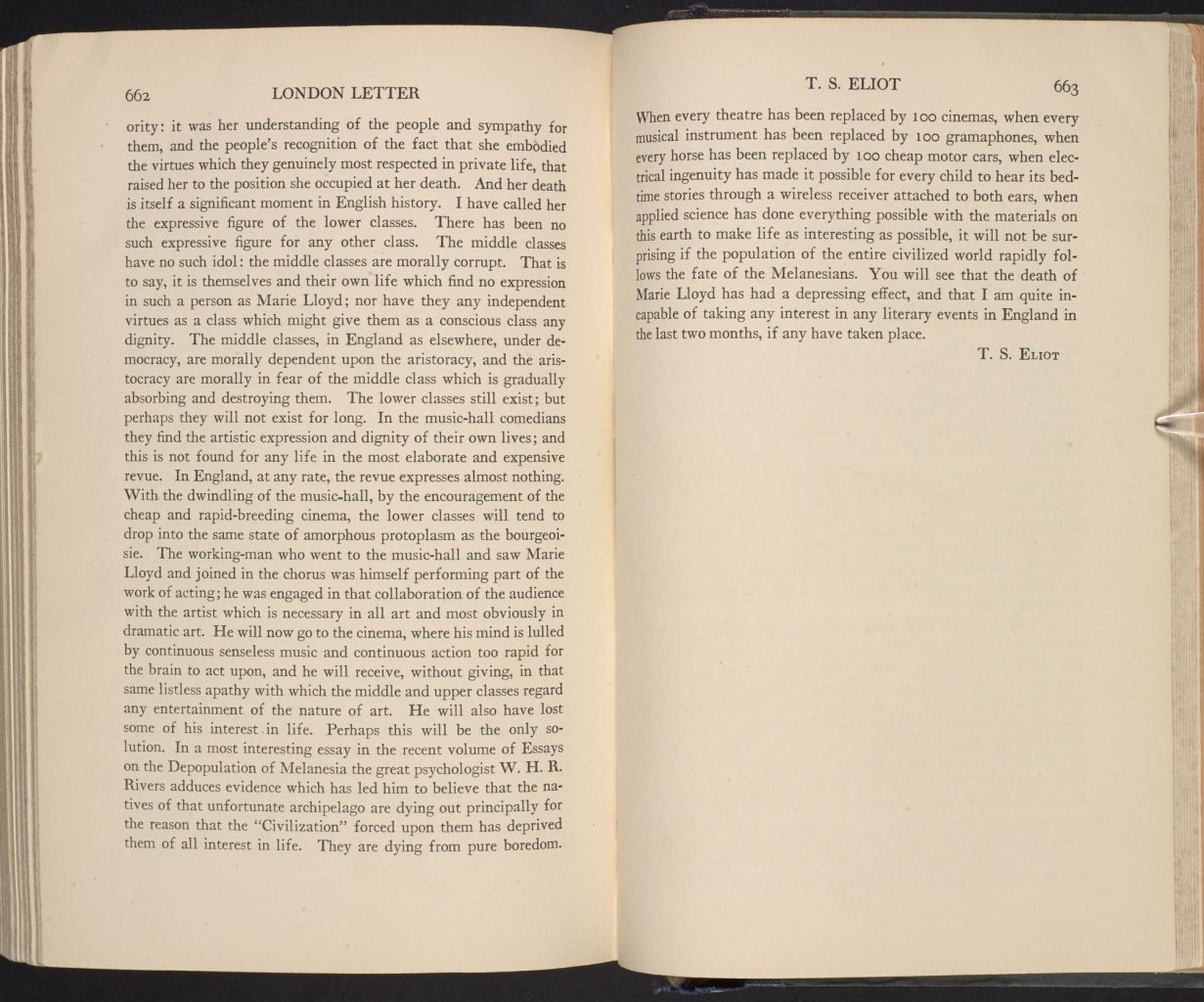

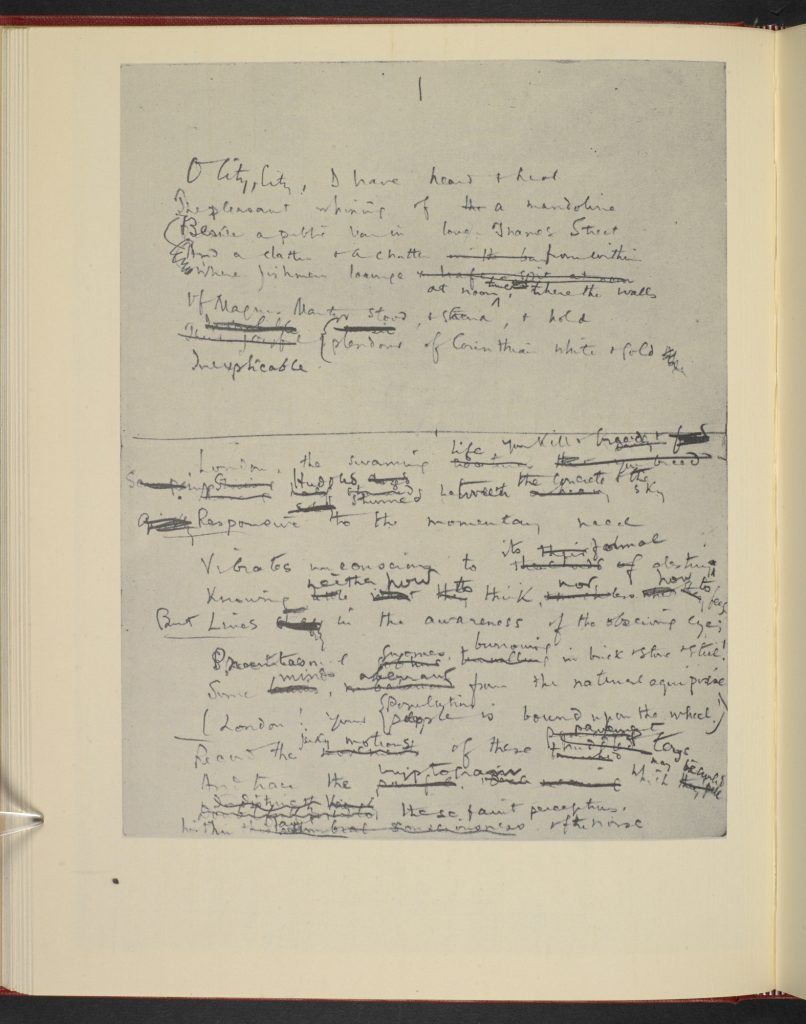

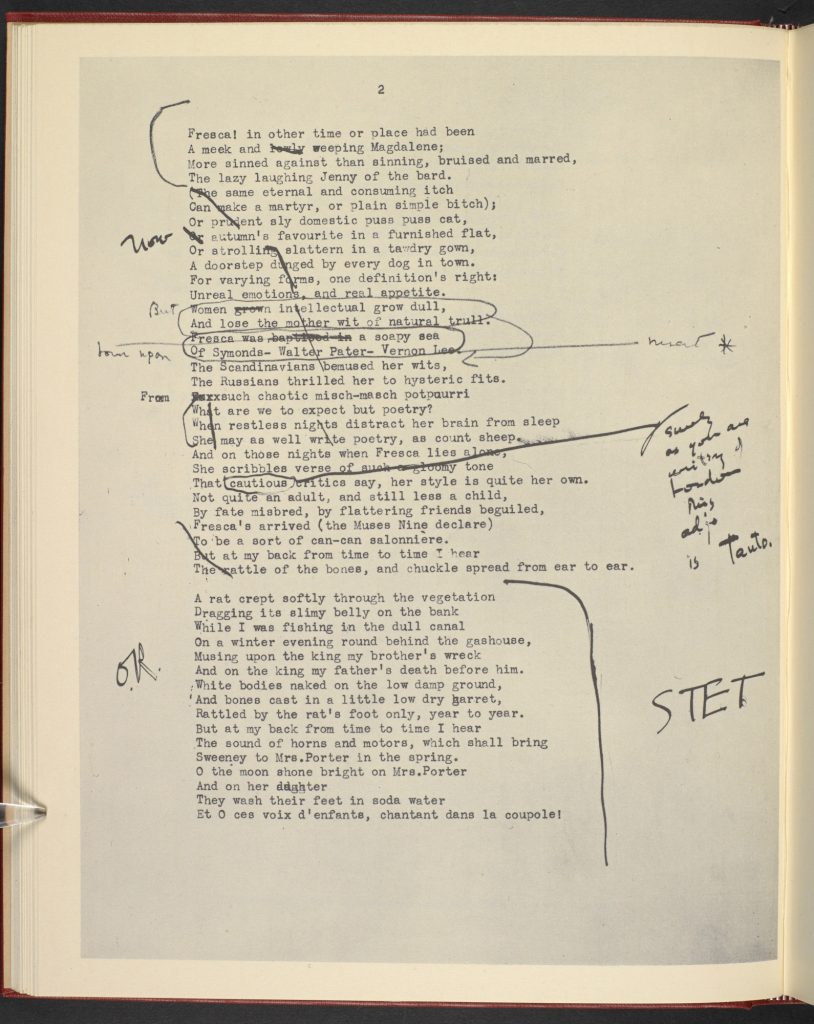

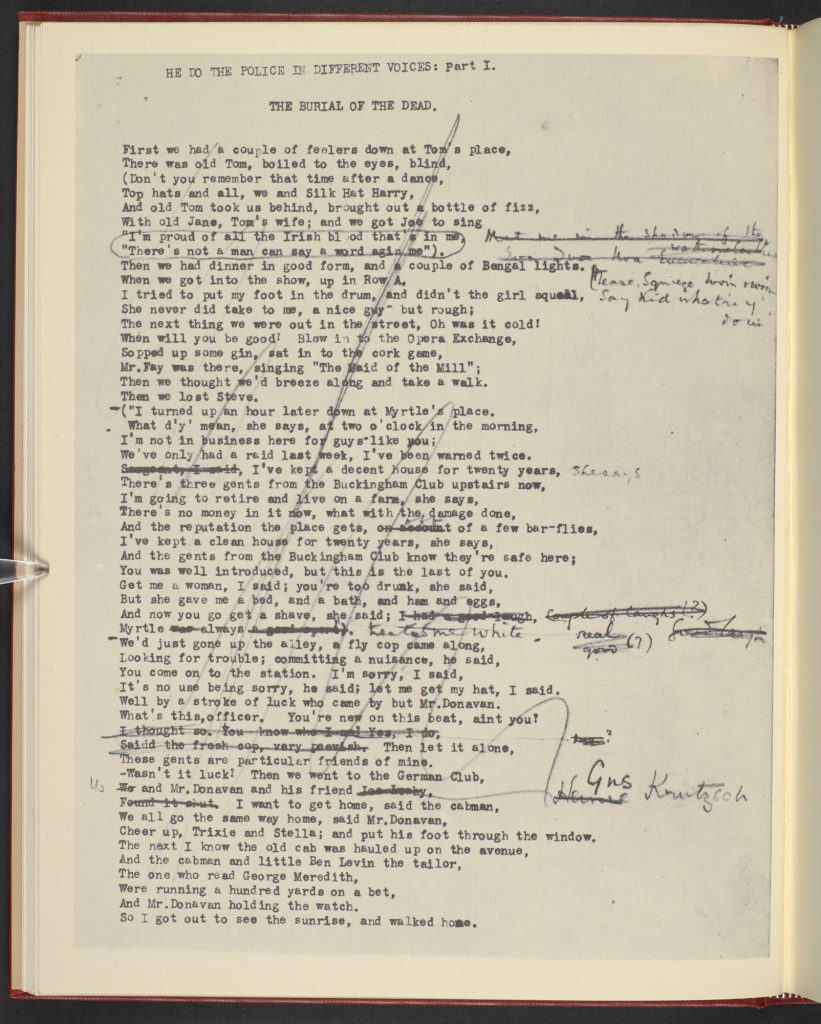

Writing on ‘The Music of Poetry’ in 1942, Eliot stated ‘I think a poet may gain much from the study of music’, but added ‘how much technical knowledge of musical form is desirable I do not know, for I have not that technical knowledge myself’.[2] Instead, Eliot was more at home with popular music. A friend, Robert Giroux, recalled him singing, in a single evening, ‘the verses of more Cohan songs than I knew existed’.[3] George M Cohan was a prodigious popular lyricist, and the impact of his genre was evident in an early draft of The Waste Land, which opened with lines from three hits, ‘My Evaline’ (1901), ‘By the Watermelon Vine’ (1904) and ‘The Cubanola Glide’ (1909).[4] These snatches of song were excised from the final revision, yet traces remain in the poem’s borrowings from music hall, ragtime and jazz.

The influence of music hall

Music hall shadows The Waste Land‘s overall construction. Variety entertainment involved a sequence of disconnected acts: a sentimental love song might give way to a comic turn, a psychic, or a magician. The Waste Land, switching rapidly between scenes and registers, and with star turns including Madame Sosostris and her ‘wicked pack of cards’, and Lil’s malevolent interrogator, resembles the music hall stage in both its structure and its diverse voices.

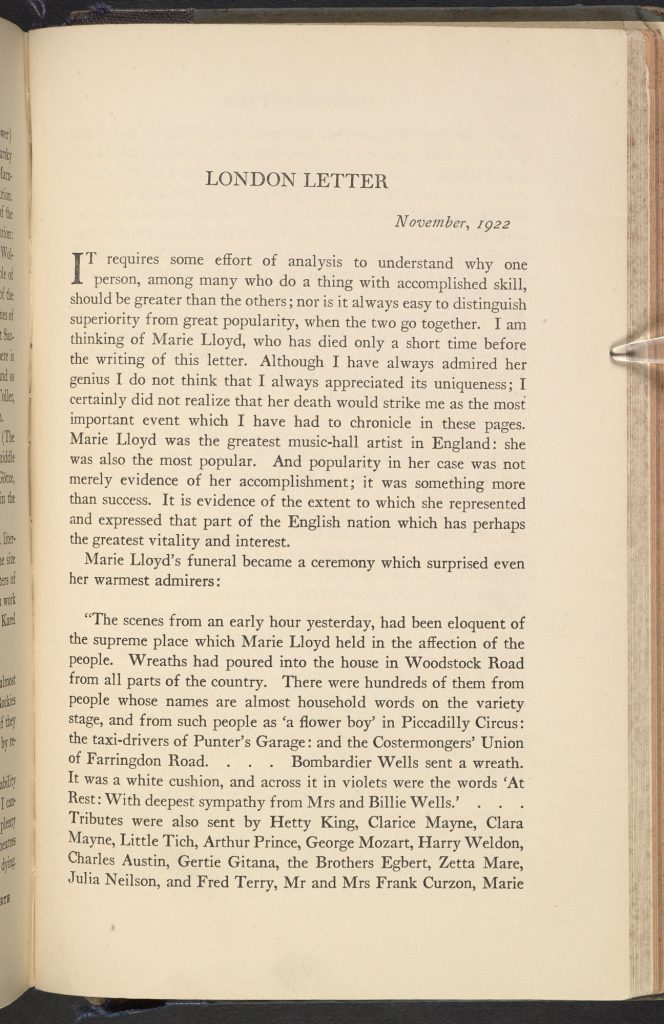

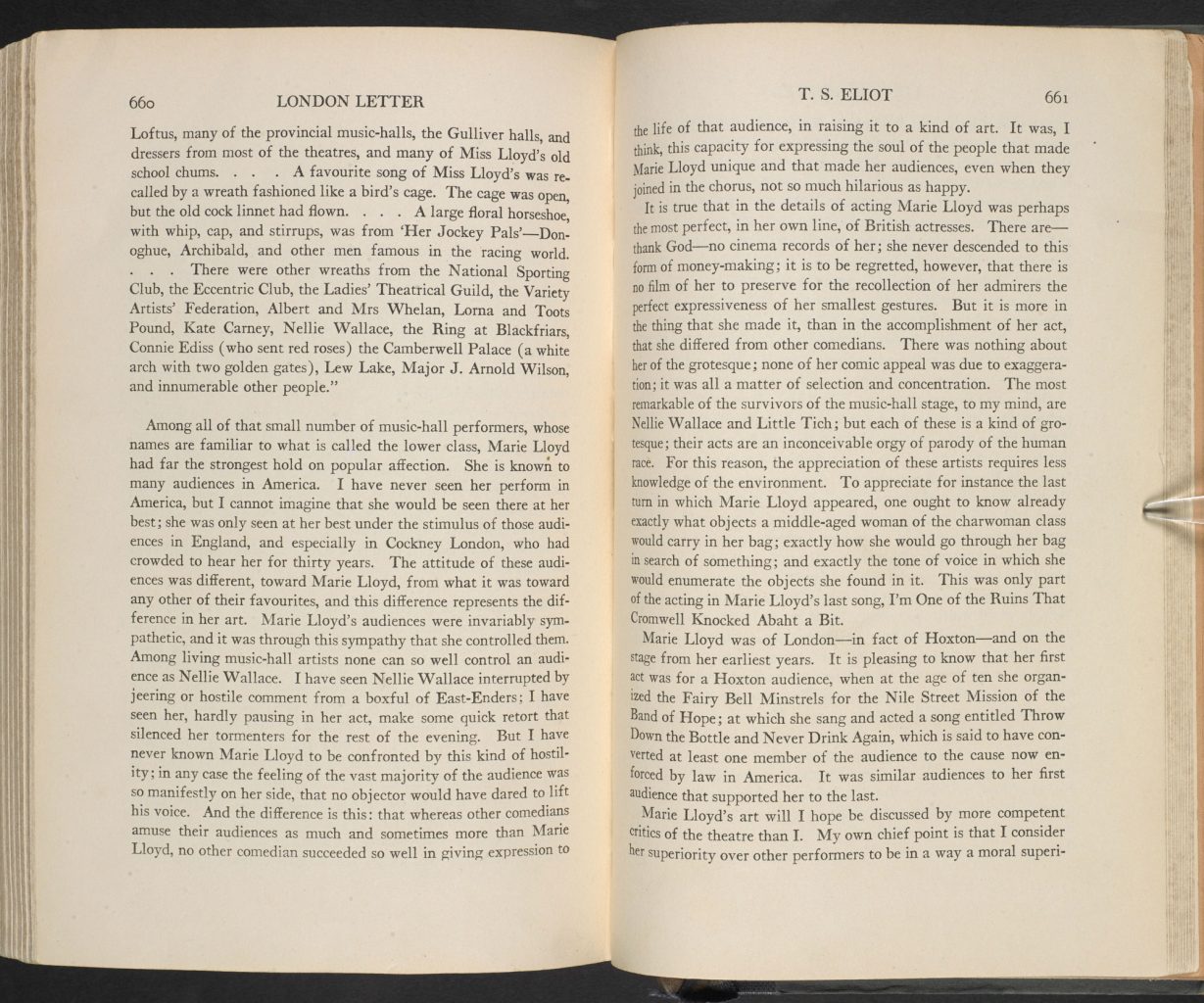

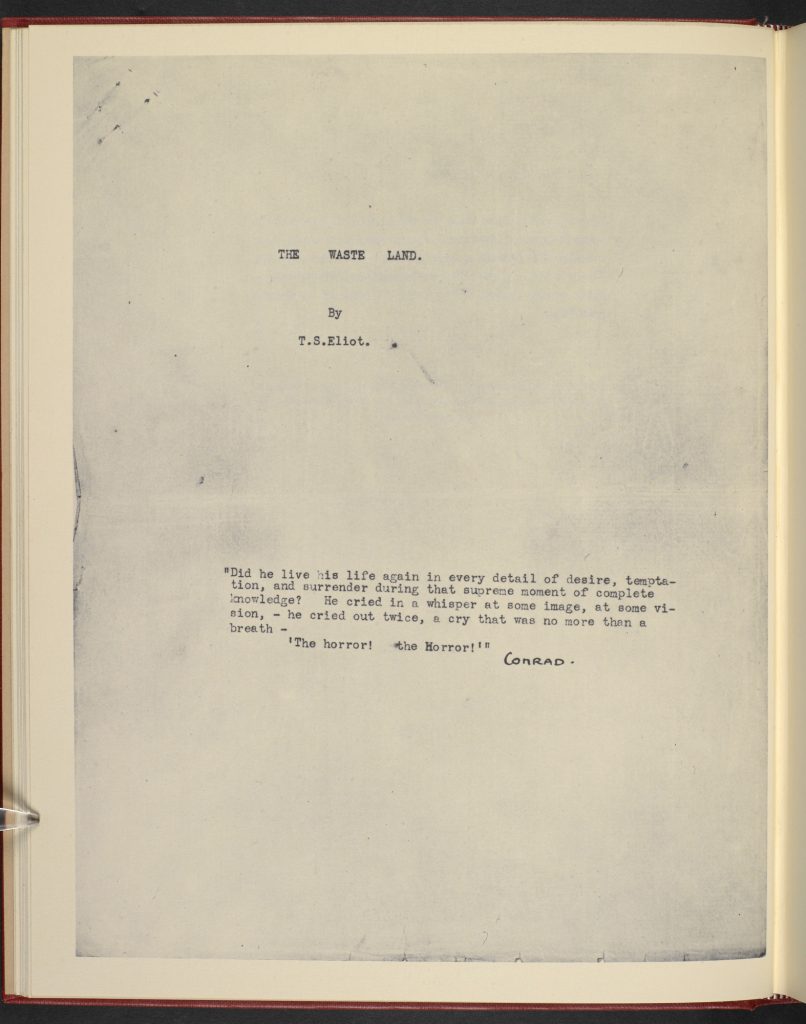

A few months after The Waste Land appeared, Eliot published an elegy for music hall star Marie Lloyd. Lloyd’s talent, he argued, was for perfect comic impersonation:

To appreciate for instance the last turn in which Marie Lloyd appeared, one ought to know already exactly what objects a middle-aged woman of the charwoman class would carry in her bag; exactly how she would go through her bag in search of something; and exactly the tone of voice in which she would enumerate the objects she found in it.[5]

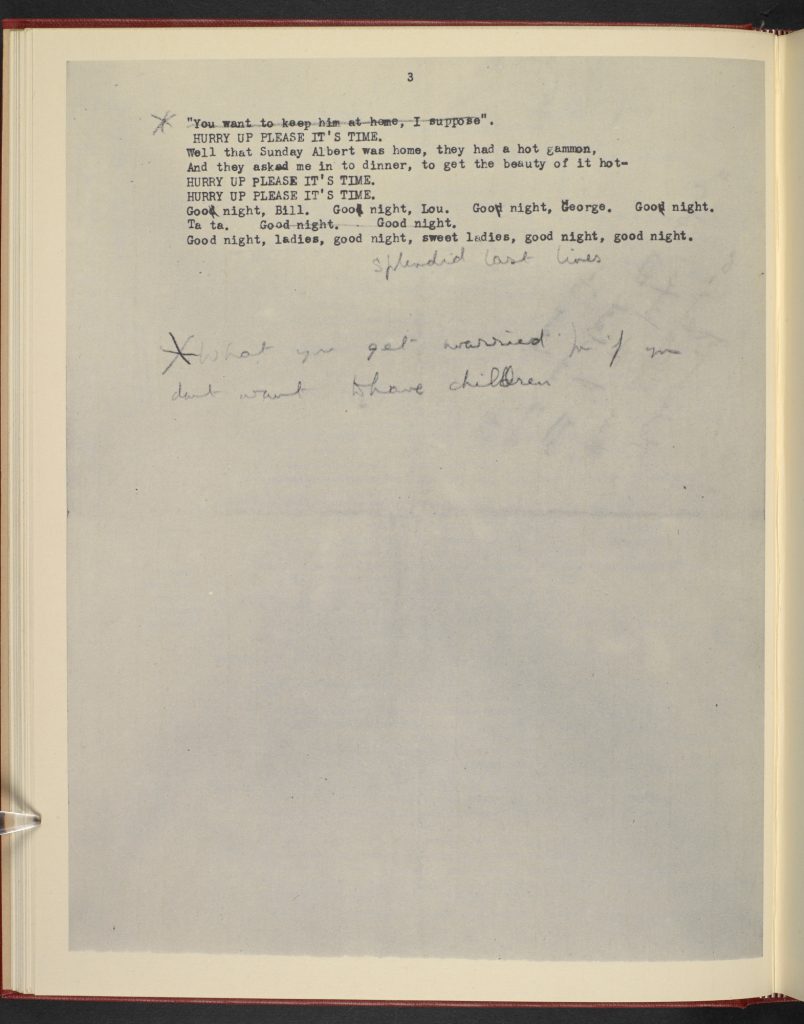

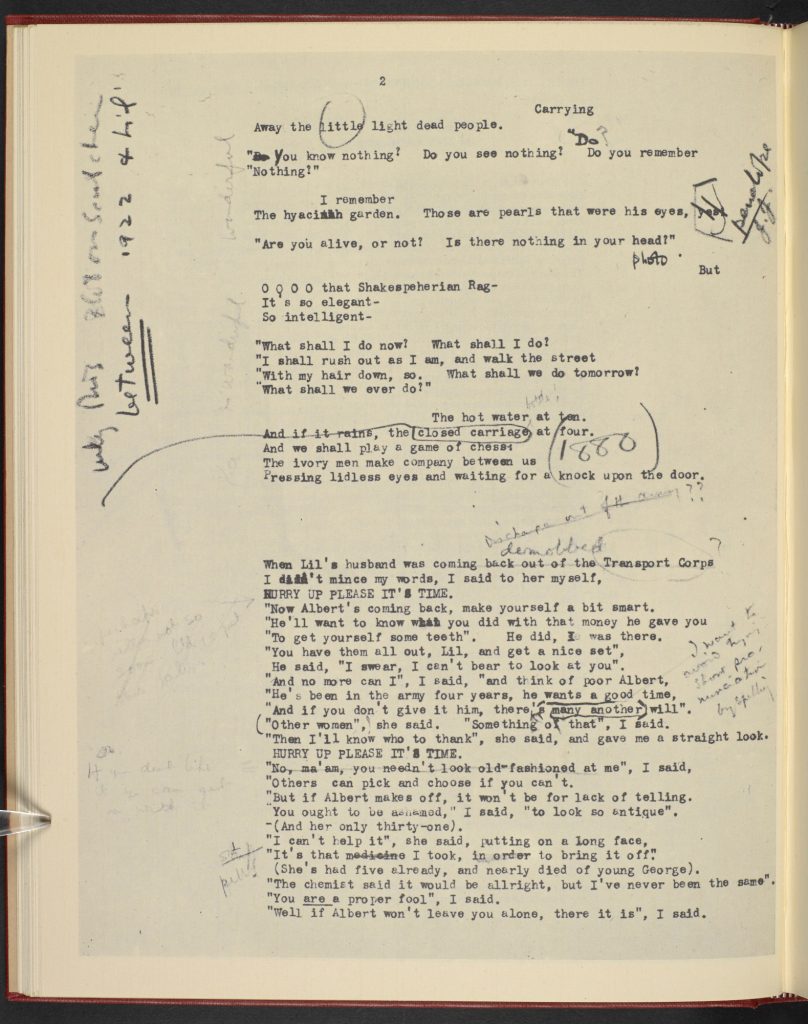

The Waste Land was first published four days after Lloyd’s spectacular public funeral, and to Eliot she was both artist and inspiration. His first draft was titled ‘He Do the Police in Different Voices’, a quotation from Charles Dickens‘s Our Mutual Friend (1864). The poor widow Betty Higden pays tribute to her adoptive son Sloppy, who is ‘a beautiful reader of a newspaper’.[6]‘Different voices’ describes Sloppy’s dramatic renditions; the phrase also captures vivid, improvised music hall routines. Marie Lloyd’s act as ‘a middle-aged woman of the charwoman class’ is echoed in the closing Lil and Albert section of ‘A Game of Chess’:

When Lil’s husband got demobbed, I said –

I didn’t mince my words, I said to her myself,

HURRY UP PLEASE ITS TIME. (ll. 139–41)

‘O O OO that Shakespeherian Rag–’

Music hall, as Eliot‘s elegy for Marie Lloyd observed, was being displaced by other forms of mass entertainment. While Eliot dreaded a time when ‘every musical instrument has been replaced by 100 gramaphones [sic]’, he relished the thrill of the new.[7] When in January 1920 Eliot was jokingly invited to attend a Bloomsbury party as a troubadour carrying a lute, he replied ‘it is a jazz-banjorine that I should bring’.[8] In The Waste Land, ‘the pleasant whining of a mandoline’ (l. 261) is in counterpoint with this ‘jazz-banjorine’, as tradition duets with innovation. The overwriting of past with present is flaunted in some of the poem’s most famous lines:

O OOO that Shakespeherian Rag–

It’s so elegant

So intelligent. (ll. 128–30)

The extra syllable implies how Shakespeare – and the cultural capital he represents as England’s national writer – has been ‘ragged’ out of its former shape, restructured through syncopation into novelty. To African-American writer Ralph Ellison, The Waste Land was remarkable in that ‘its rhythms were often closer to jazz than those of the Negro poets’.[9]

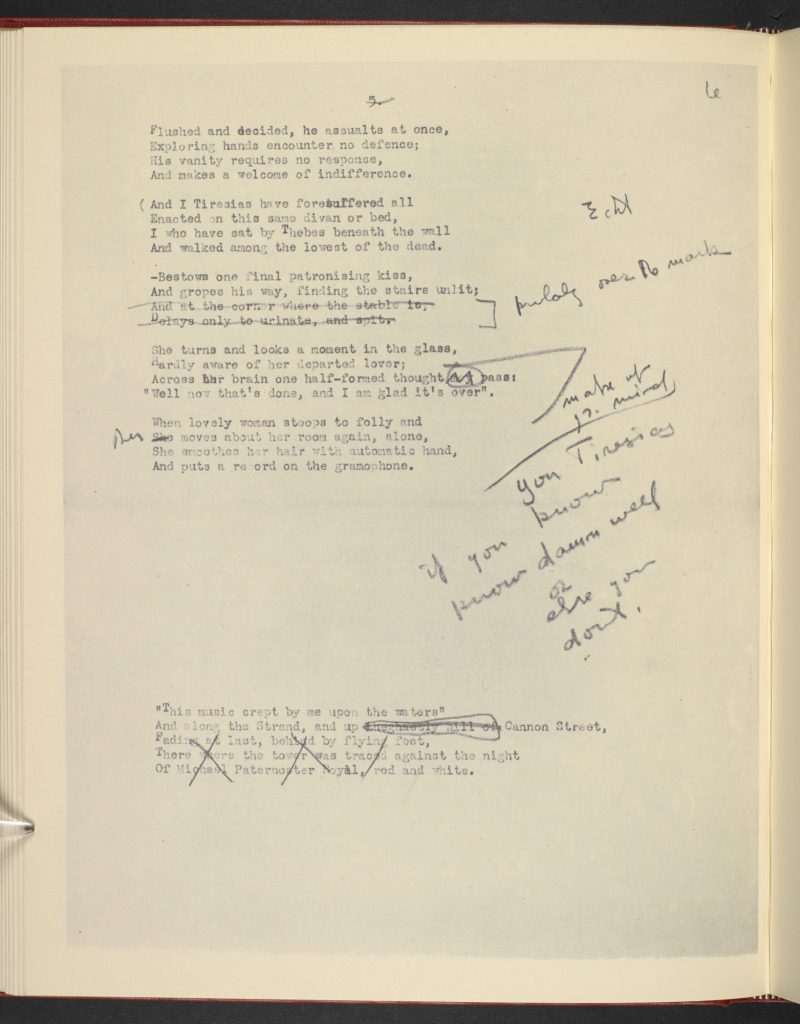

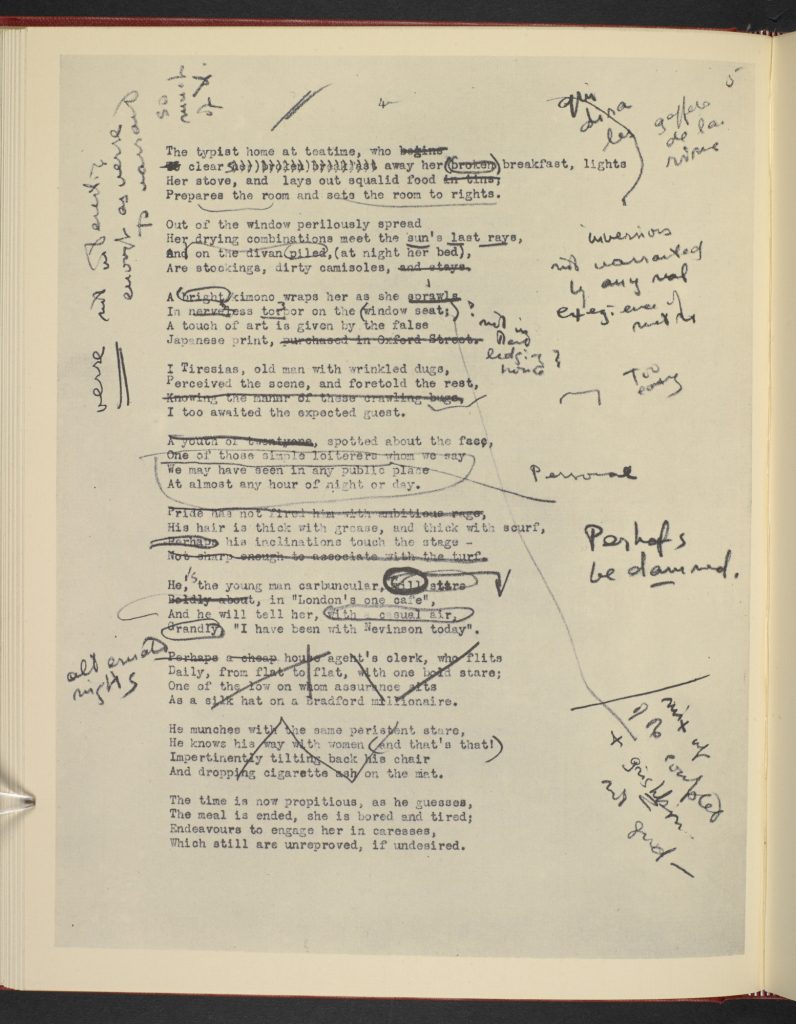

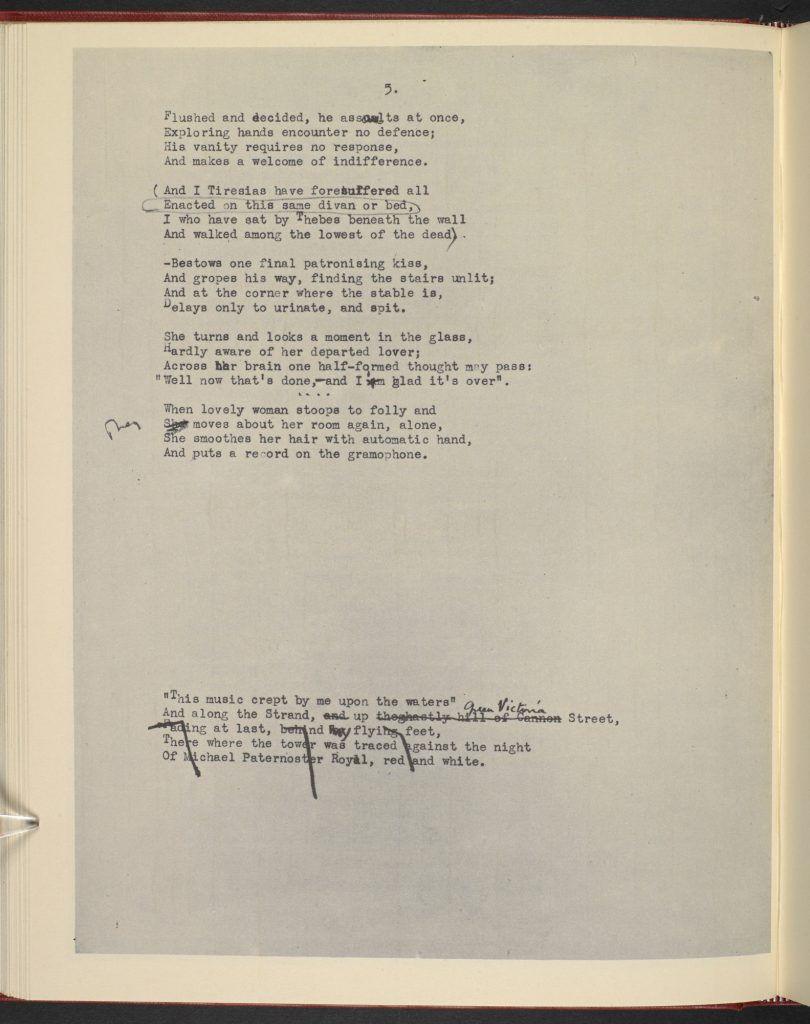

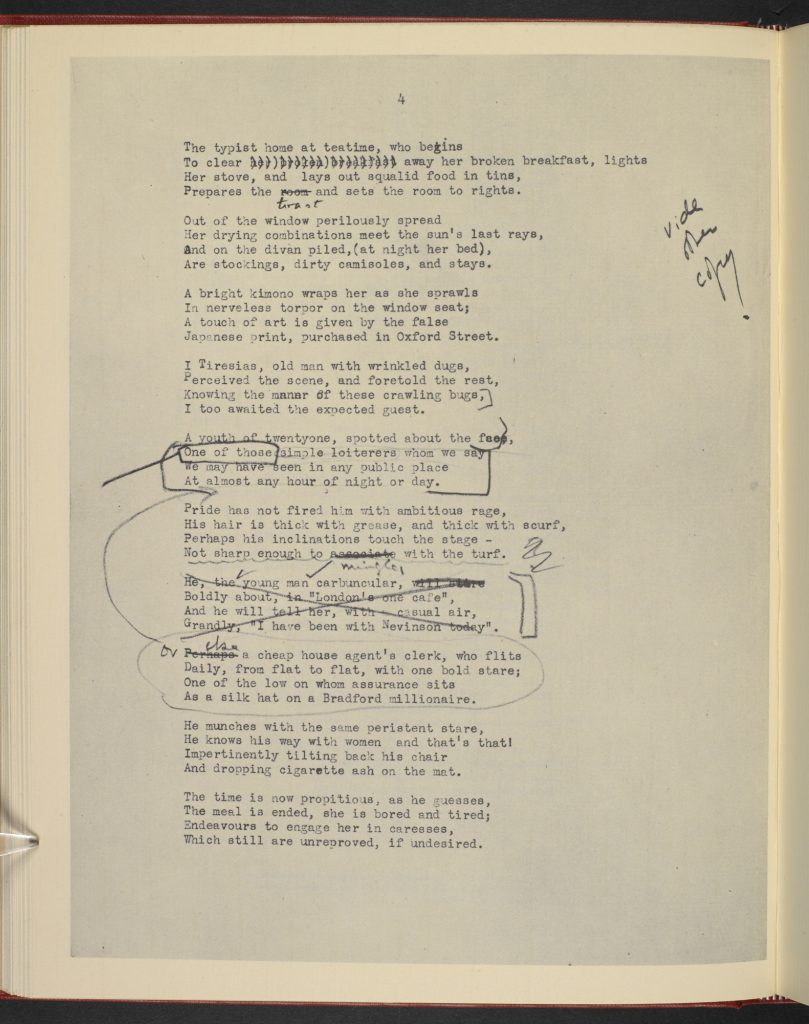

Ragtime, and the genre developing from it, jazz, inspired The Waste Land‘s angular rhythms and sudden, insistent rhymes. ‘The Fire Sermon’ describes an attenuated sexual encounter between a ‘ragtime’ couple, the typist and her ‘young man carbuncular’ (l. 231), rendered in the mode of the music they might favour:

The time is now propitious, as he guesses,

The meal is ended, she is bored and tired,

Endeavours to engage her in caresses

Which still are unreproved, if undesired.

Ragtime ‘licensed the vernacular as a lyrical idiom’, its lyrics characterised by ‘short, juxtaposed phrases marked by internal rhymes and jagged syntactical breaks’.[10] Eliot‘s lines – short, syncopated, tightly rhyming – have the characteristic ‘swing’, and, sure enough, once her lover has departed, the typist ‘smooths her hair with automatic hand / and puts a record on the gramophone’ (ll. 255–56).The tryst between the couple was described in Eliot‘s notes to The Waste Land as ‘the substance of the poem’: its style is insistently contemporary.

Time present and time past

Often, The Waste Land‘s sounds seem timeless. The final section, ‘What the Thunder Said’, resonates with ahistorical natural phenomena: ‘dry sterile thunder without rain’ (l. 342), ‘the sound of water’ (l. 352), ‘the cicada / And dry grass singing’ (ll. 353–54), ‘the hermit thrush’ (l. 356), a ‘Murmur of maternal lamentation’ (l. 367), ‘reminiscent bells’ (l. 384), the ‘Co co rico co corico’ (l. 392) of a cockerel. These cries, calls, songs, chimes and rumbles contrast with the nowness of music hall’s knowing bawdy, or the urgent glamour of ragtime. The difference attests to The Waste Land‘s ambition to synthesise tradition and modernity. The solidity of established culture is deconstructed into ‘fragments’, ‘ragged’ out of original context, made ‘Shakespeherian’. But these fragments are re-energised by the vitality of an evolving popular music, reconfigured in a new arrangement of voices and sounds.

The Waste Land at Radio City

If the competing voices of The Waste Land make the poem resemble a radio being tuned between stations, then it is apt that Eliot should eventually have chosen the medium to interpret his poem. After initial suspicions of the new technology, Eliot wrote to the newly founded BBC in 1929 offering a series of talks. The association was to continue for the next 35 years, as Eliot delivered at least 83 programmes, attending carefully to tone and delivery as he aimed to engage, rather than lecture, his listeners.[11] In 1946, he visited the NBC Studios in New York – Radio City – to make a recording of The Waste Land. The experience afforded Eliot the opportunity to capture the ‘different voices’ of his poem for posterity. The Waste Land can, perhaps, be best experienced as a listener, allowing its musicality, syncopations and voices to be properly heard.

脚注

- Ted Hughes, A Dancer to God: Tributes to T. S. Eliot (London: Faber & Faber, 1992).

- T S Eliot, 'The Music of Poetry' (1942), in Selected Prose of T. S. Eliot, ed by Frank Kermode (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975), p. 112.

- Lyndall Gordon, Eliot's New Life (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), p. 343.

- T S Eliot, The Waste Land: A Facsimile and Transcript of the Original Drafts Including the Annotations of Ezra Pound, ed. by Valerie Eliot (London: Faber & Faber, 2011), p. 125.

- 'London Letter', The Dial, Vol. 73, no. 6, (December, 1922), p. 660.

- The Waste Land: A Facsimile, p. 125.

- 'London Letter', p. 661.

- Letters of T. S. Eliot Volume 1 (1898-1922), ed. by Valerie Eliot and Hugh Haughton (London: Faber & Faber, 2009), p. 448.

- Ralph Ellison, Shadow and Act (New York: Random House, 1964), p. 161.

- Philip Furia, The Poets of Tin Pan Alley: A History of America's Greatest Lyrics (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), p. 49.

- Michael Coyle, 'This rather elusory broadcast technique: T S Eliot and the genre of the Radio Talk', ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes and Reviews, 11 (1998), 32-42.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Katherine Mullin

Dr Katherine Mullin teaches Victorian and Modernist literature at the University of Leeds. She is the author of James Joyce, Sexuality and Social Purity (Cambridge University Press, 2003) and Working Girls: Fiction, Sexuality and Modernity (Oxford University Press, 2016).