The campaign for women’s suffrage

Discover how suffrage campaigners of the 19th and 20th century secured women’s right to vote in the UK. Who was involved in the campaign, what were they fighting for and what methods did they use?

Today, all British citizens over the age of 18 share a fundamental human right: the right to vote and to have a voice in the democratic process. But this right is only the result of a hard fought battle. The suffrage campaigners of the 19th and early 20th century, including the Chartists, suffragists and suffragettes, struggled against opposition from both parliament and the general public to eventually gain the vote for the entire British population in 1928.

Who took part in the campaign for women’s suffrage?

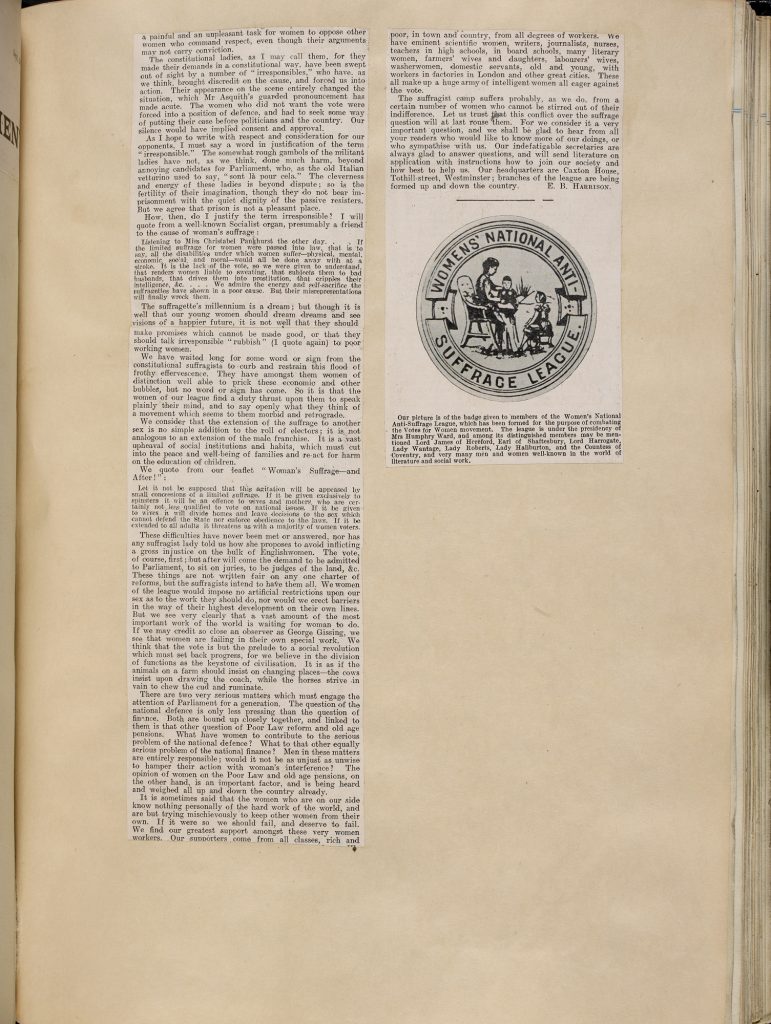

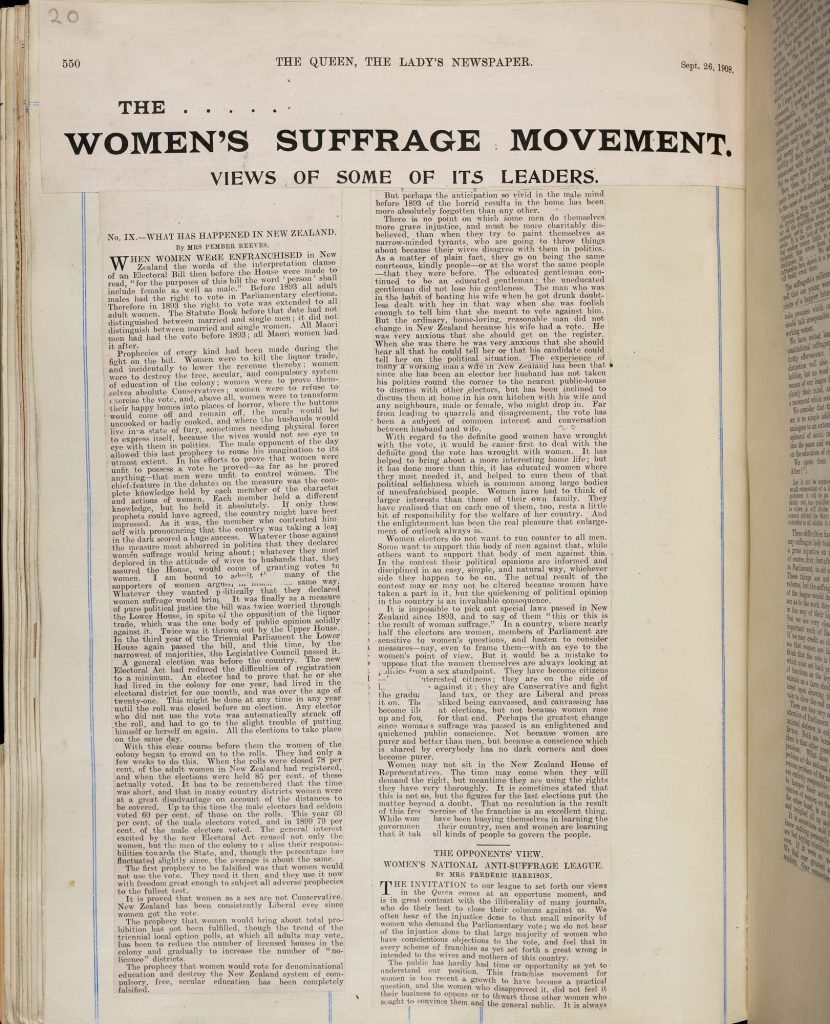

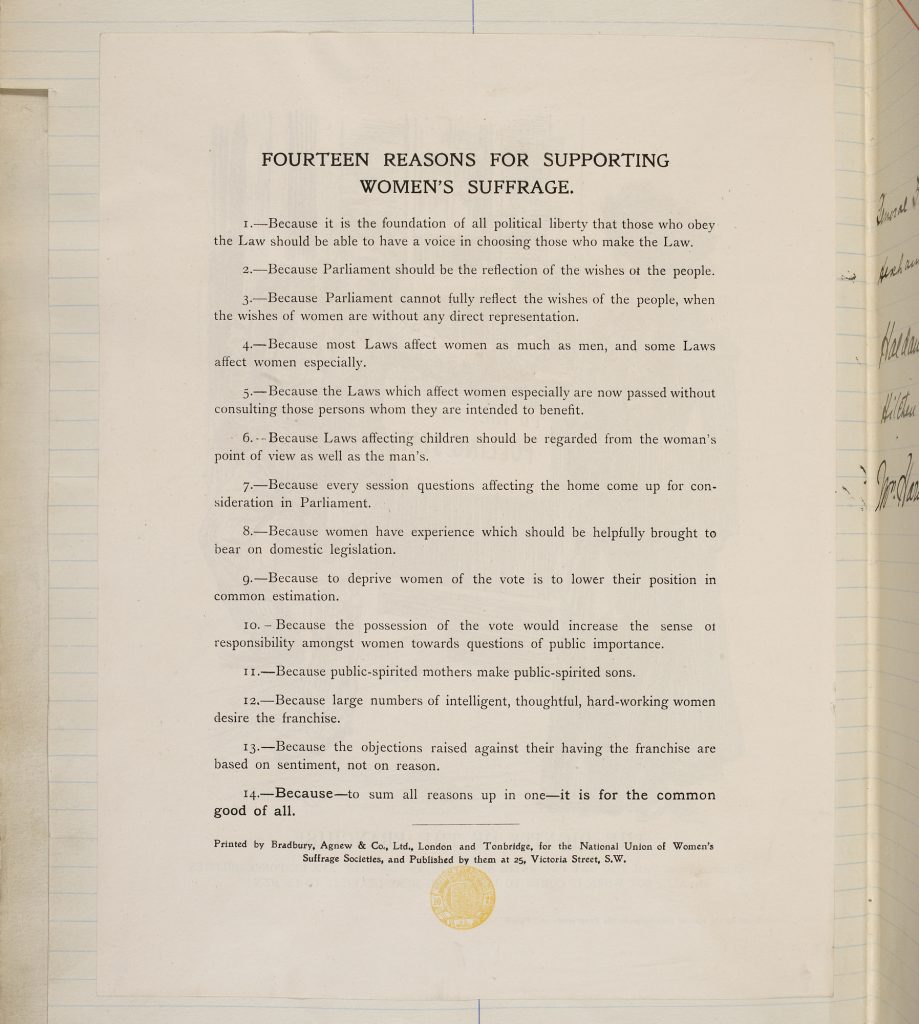

Groups and societies dedicated to the cause of women’s suffrage had formed in the late 1860s. The first women’s suffrage bill, however, came before parliament in 1832. In 1867 John Stuart Mill led the first parliament debate on women’s suffrage, arguing for an amendment to the Second Reform Bill, which would have extended the vote to women property holders. Mill’s proposed amendment was defeated – but acted as a catalyst for campaigners around Britain. In 1897, various local and national suffrage organisations came together under the banner of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) specifically to campaign for the vote for women on the same terms ‘it is or may be granted to men’. The NUWSS was constitutional in its approach, preferring to hold public meetings and lobby parliament with petitions.

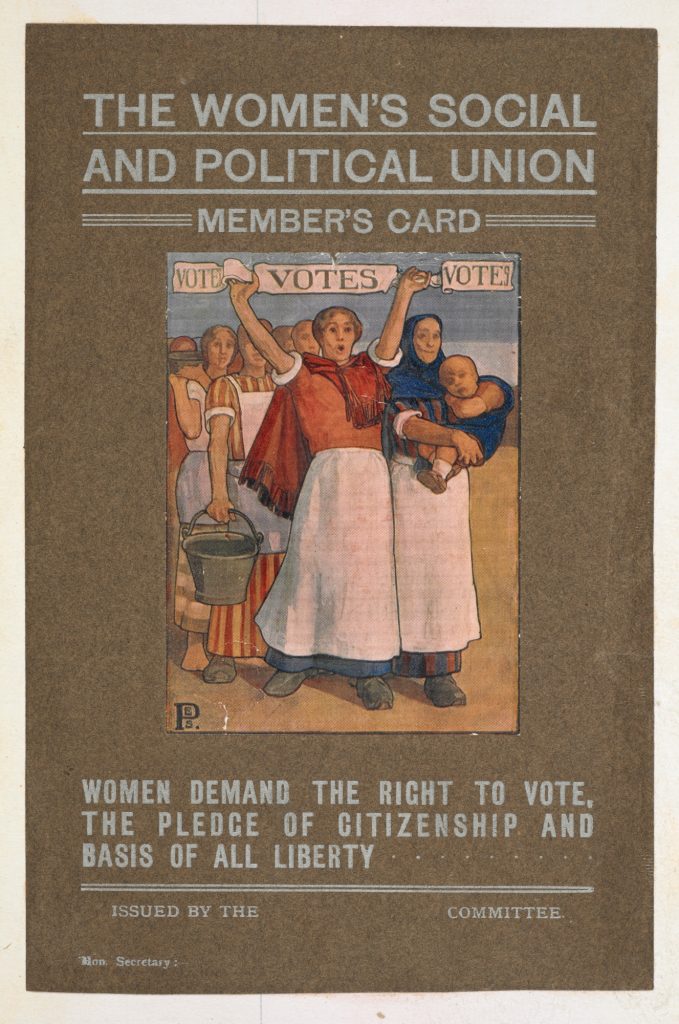

In contrast, the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), formed in 1903, took a more militant view. Almost immediately, it characterised its campaign with violent and disruptive actions and events, known as ‘direct action’.

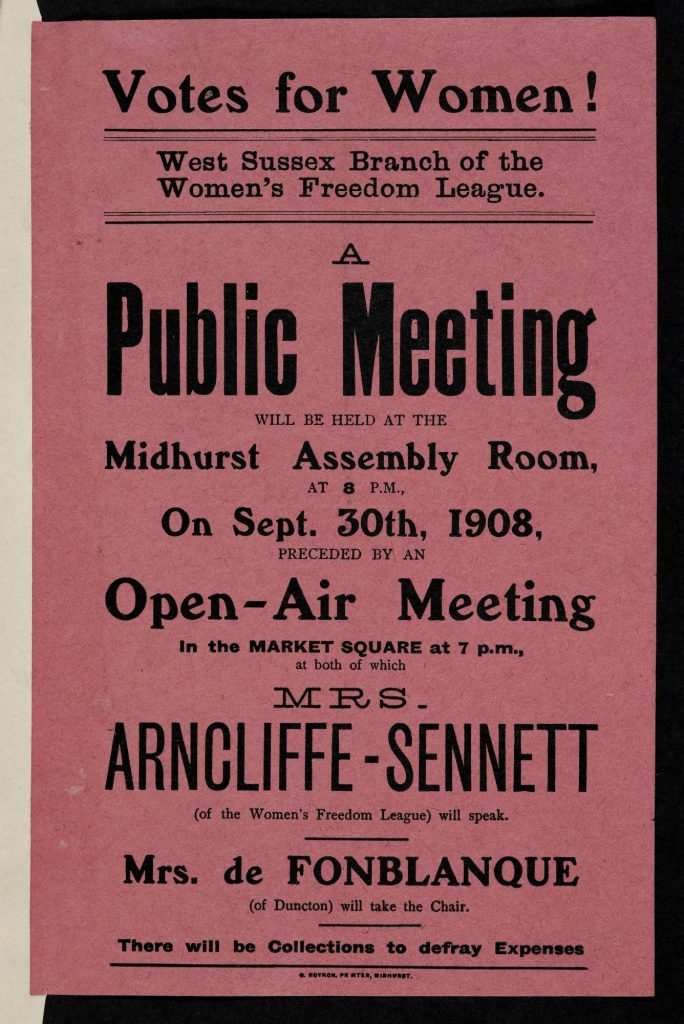

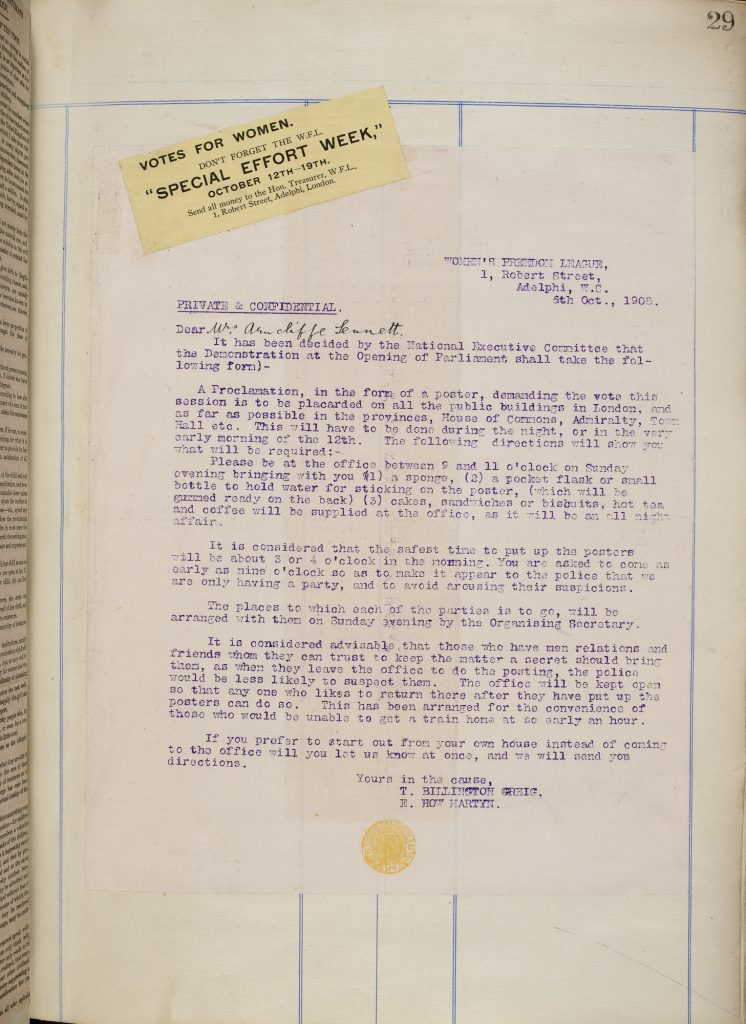

Together, these two organisations dominated the campaign for women’s suffrage and were run by key figures such as the Pankhursts and Millicent Fawcett. However, there were other organisations prominent in the campaign, including the Women’s Freedom League (WFL). These groups were often splinter groups of the two main organisations.

What did they campaign for?

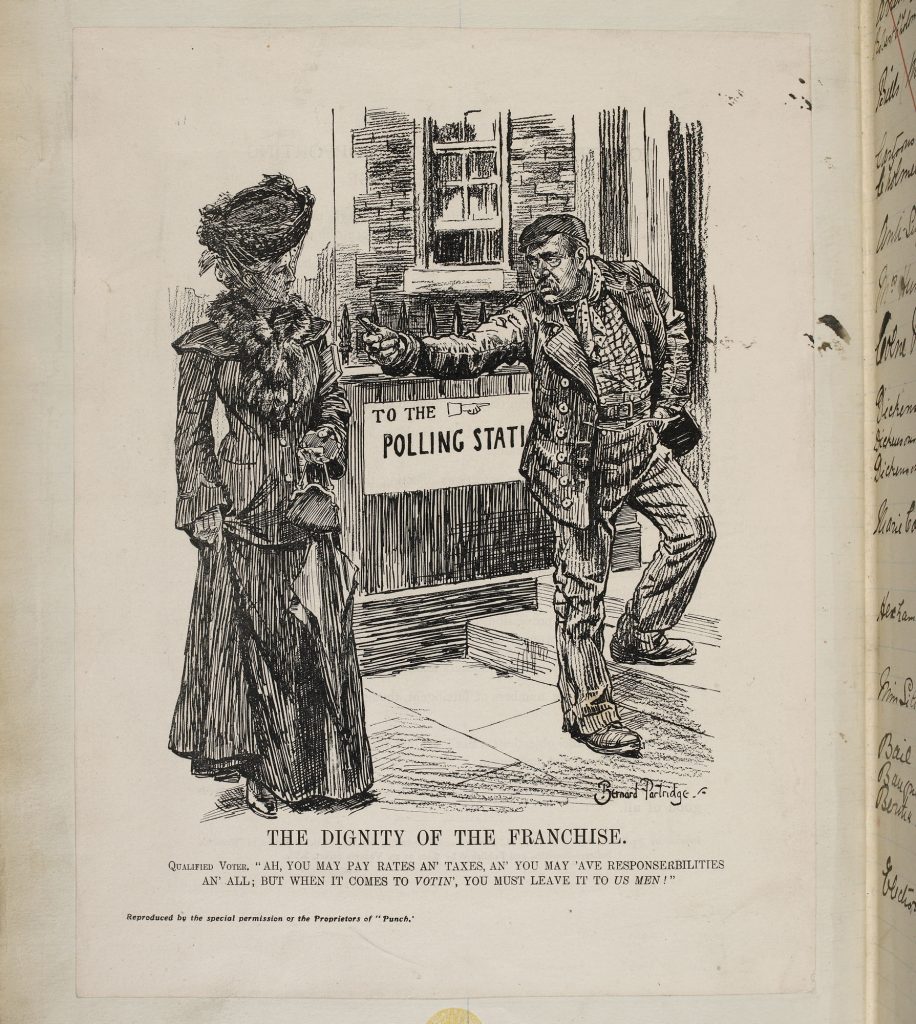

Before the first of a series of suffrage reforms in 1832, only 3% of the adult male population were qualified to vote. For the most part, the right to vote depended on how much you earned and the value of your property. For this reason, the majority of people who were able to vote were both wealthy and male. Throughout the 1800s, campaigners fought to extend the franchise and some concessions were made in 1867 and 1884. However, under these reforms women were still denied the vote and an increasing number of groups began campaigning for just that.

Campaigners for women’s suffrage initially wanted the vote for women on the same terms as it was granted to men. This is because many of the original campaigners for women’s suffrage were female middle-class homeowners. Their priority was that the franchise should be extended to women of their own status rather than to all women. This version of reform did not include either working-class men or women but, eventually, universal suffrage – votes for all – became the goal of the campaign.

Why were they campaigning?

The inability to vote meant that Victorian women had very few rights and their disenfranchised status became a symbol of civil inequality. The denial of equal voting rights for women was supported by Queen Victoria who, in 1870, wrote, ‘Let women be what God intended, a helpmate for man, but with totally different duties and vocations’. Campaigners wanted the vote to be granted to women as they felt that too often the law was biased against women and reinforced the idea of women as subordinate to men. For example, until 1882, a woman’s property often reverted to her husband on their marriage. Steps towards equal rights came with the Married Woman’s Property Acts of 1870, 1882 and 1884 (amended again in 1925). These enabled women to keep their property and money after marriage, where previously it was the automatic property of their husbands. Even after the Married Women’s Property Act of 1882, however, the situation was not much improved – women now had to pay taxes on the businesses the new law permitted them to own, but did not have any say in how those taxes were spent. Campaigners felt that the best way to achieve equal status with men, in society and in the home, would be to get the vote and participate in the parliamentary process.

How did they campaign?

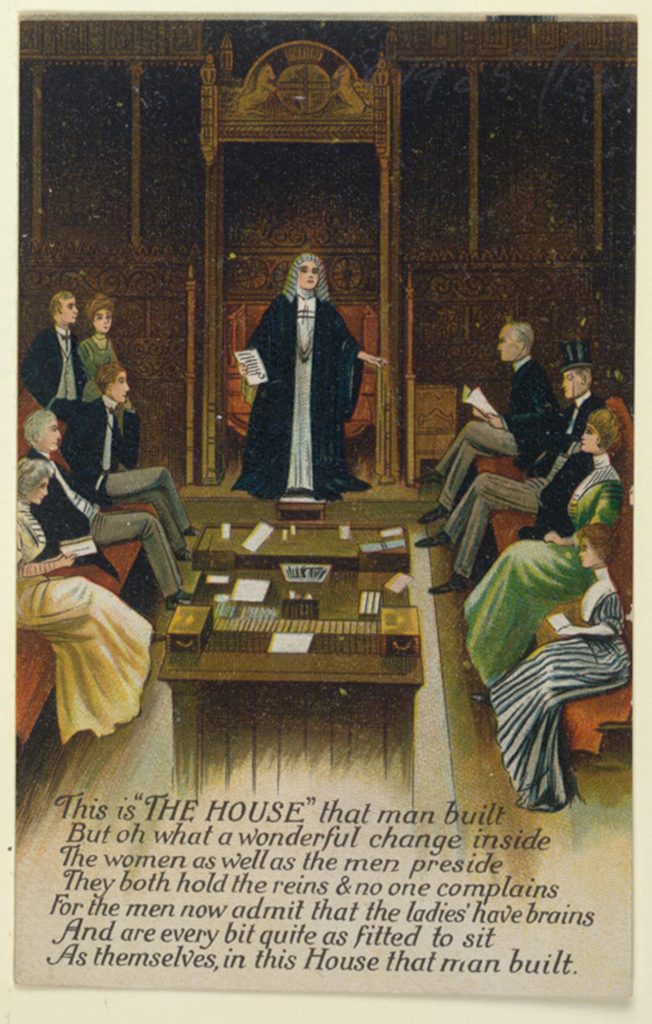

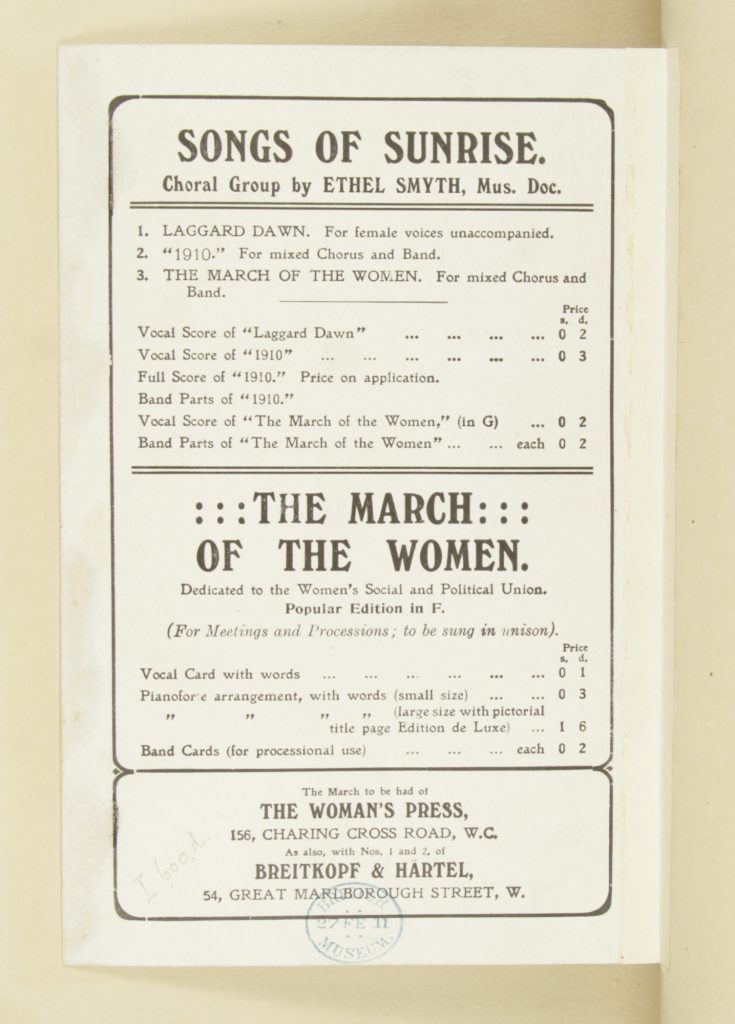

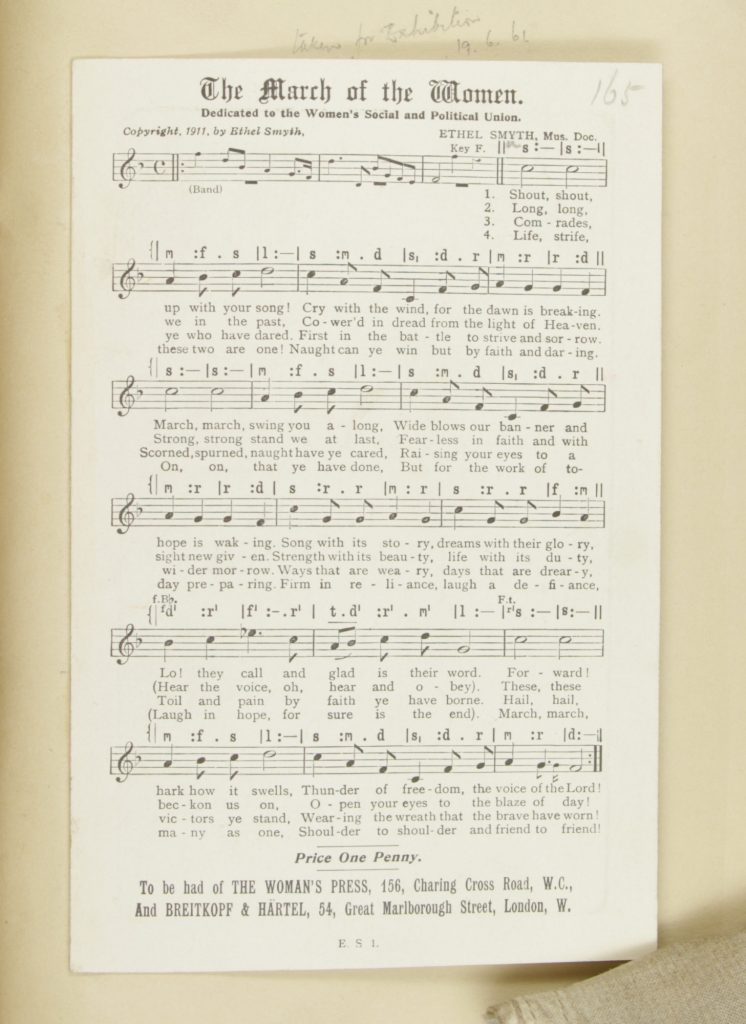

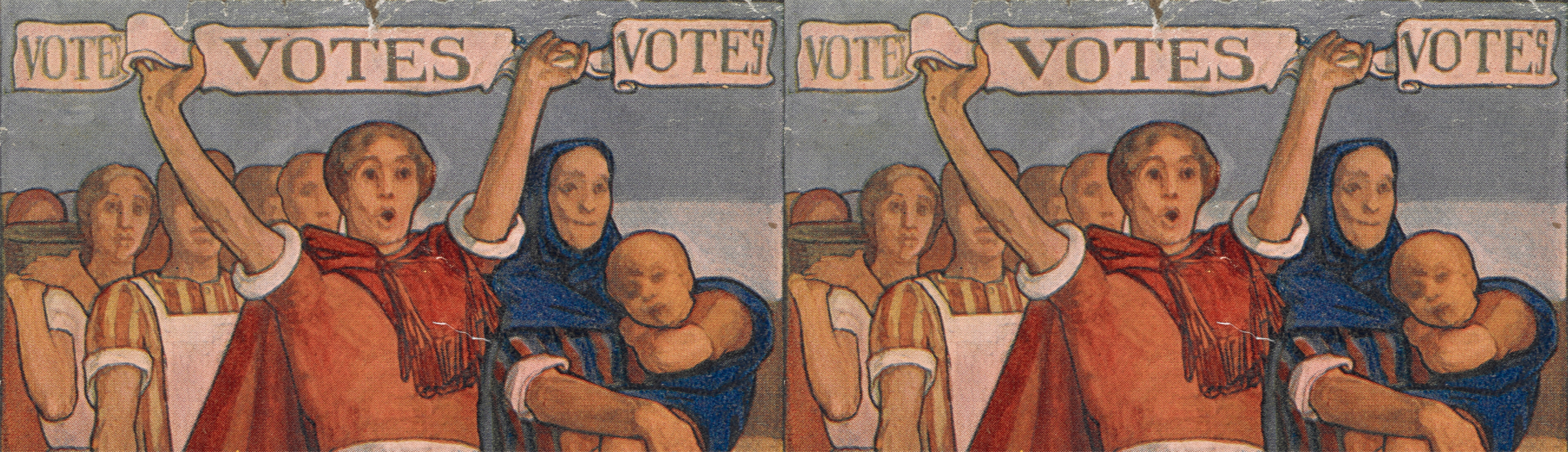

The campaign for women’s suffrage took several forms and involved numerous groups and individuals. The constitutional National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) campaigned peacefully and used recognised ‘political’ methods such as lobbying parliament and collecting signatures for petitions. The group also held public meetings and published various pamphlets, leaflets, newspapers and journals outlining the reasons and justifications for granting women the vote. Members of the NUWSS and other such organisations were known as ‘suffragists’.

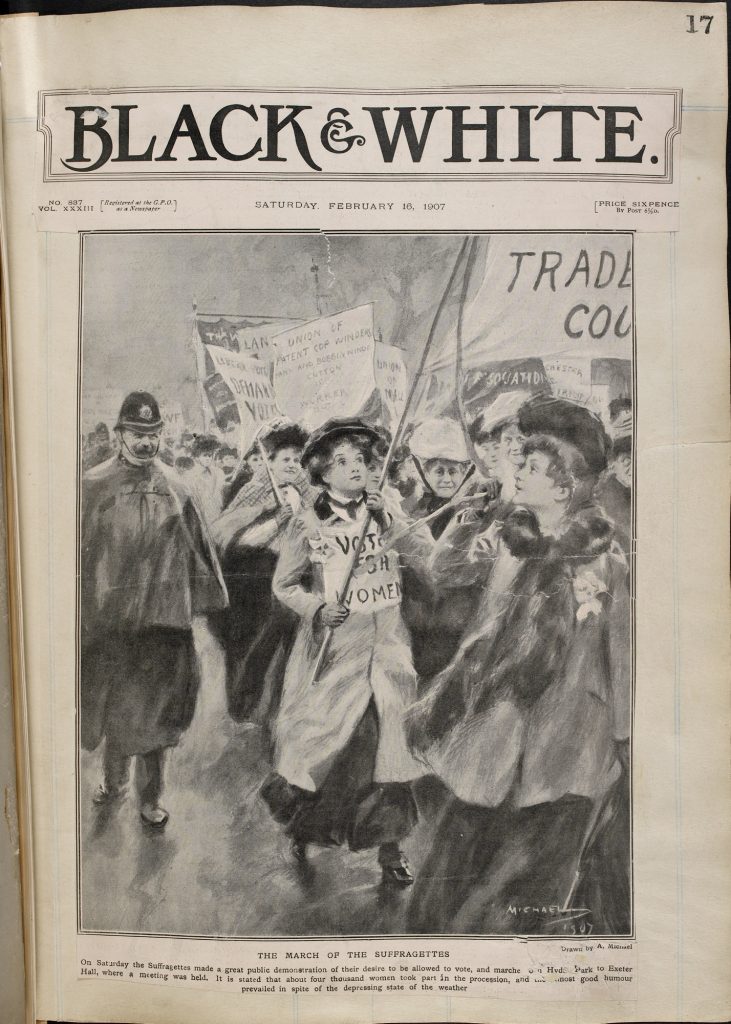

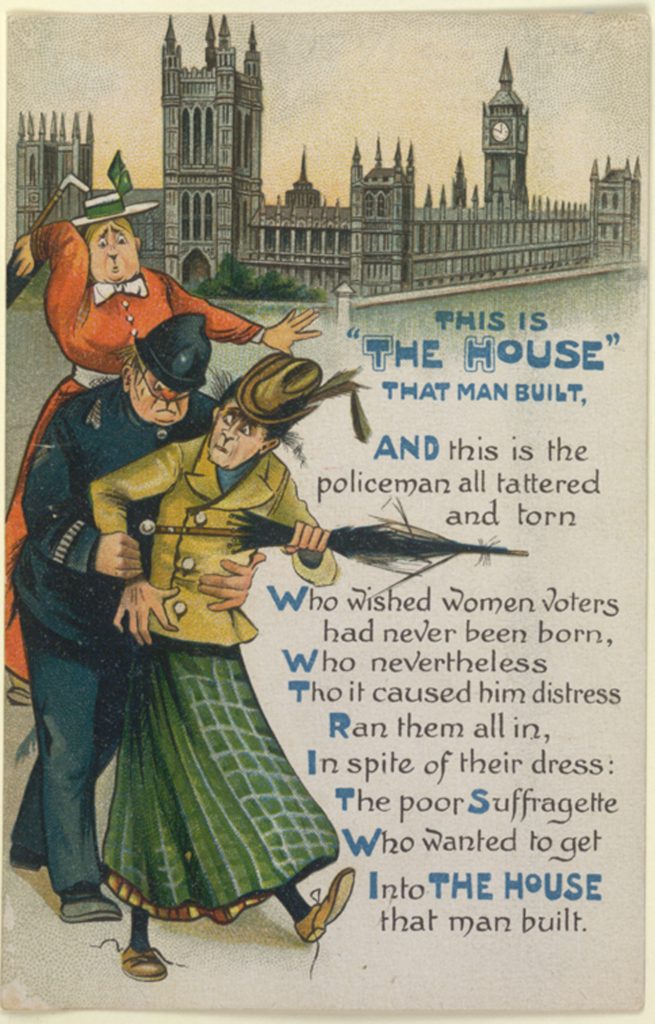

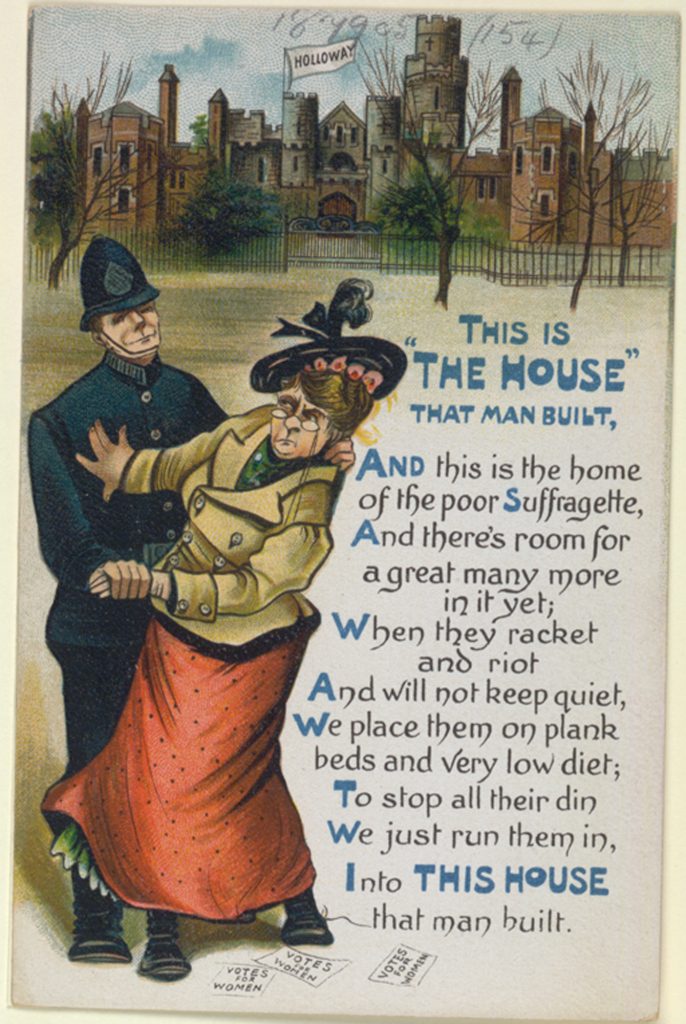

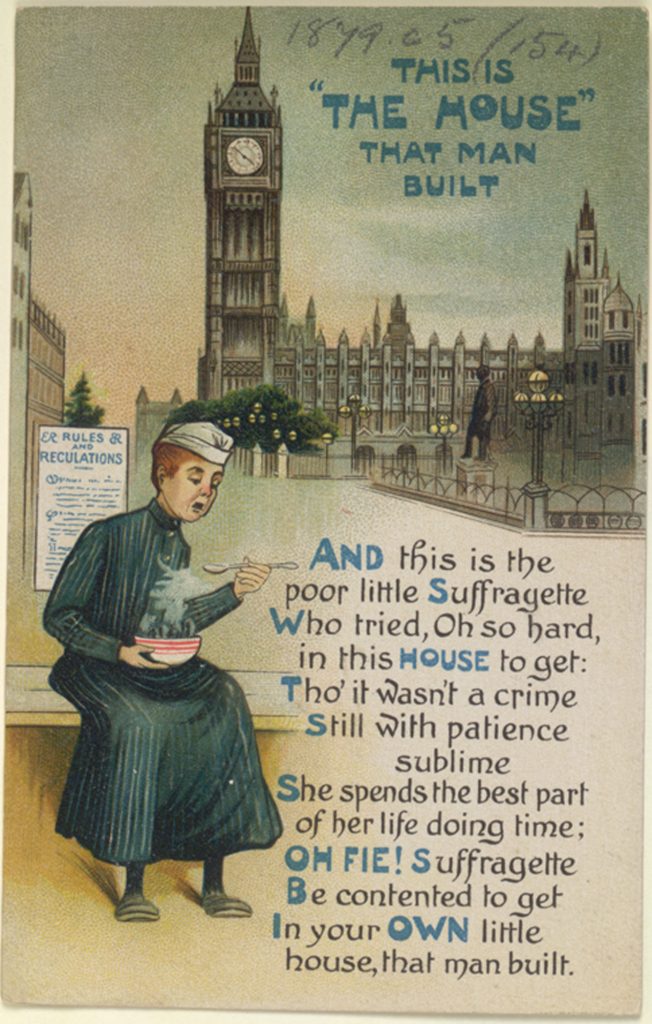

In order to gain publicity and raise awareness, the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) engaged in a series of more violent actions. They chained themselves to railings, set fire to public and private property and disrupted speeches both at public meetings and in the House of Commons. Alongside this, the WSPU also took part in demonstrations, held public meetings and published newspapers and other literature. Members of the WSPU and other militant groups such as the Women’s Freedom League were known as ‘suffragettes’.

Many suffragettes went to prison as a result of their actions and their campaigns did not always stop there. While in prison, many women chose to go on hunger strike to continue gaining publicity for their cause and as a result were sometimes force fed. One of the most infamous suffragettes was Emily Davison who, in 1913, walked out in front of the King’s horse at the Epsom Derby. She later died of her injuries and became a martyr to the cause.

When did this happen?

As a result of campaigns dating back to the mid-19th century, some women were finally granted the vote in 1918. However, many women, particularly working-class women, were still excluded from the franchise. The Representation of the People Act enfranchised all males over the age of 21 and women over the age of 30 who already had the right to vote in local elections and who were also householders, the wives of householders, owners of property worth over £5 or university graduates. In total, the Act enfranchised 8,400,000 women. Universal franchise was finally granted with the Equal Franchise Act of 1928.

撰稿人: British Library Learning

The British Library’s Digital Learning team welcomes over 10 million learners to their website every year. They provide free learning resources that allow audiences to access thousands of digitised treasures from the British Library’s collection, and explore a wealth of subjects from children’s literature and coastal sounds to medieval history and sacred texts.