A Child from Wuzhen: Mu Xin’s voyage to England

In 1994, Mu Xin travelled to England accompanied by his student, Mr Danqing Chen, now director of Mu Xin Art Museum. In this specially-comissioned article, Mr Chen reminisces about the good old days he spent with Mu Xin in England.

Gone are the days when smoking was allowed on airplanes. I even disbelieve that such a moment existed: at the airport in New York, swiftly processing our boarding passes, the girl at the counter mellifluously enquired: ‘Smoking or non-smoking?’

The video I made of Mu Xin’s voyage to England twenty-three years ago has recently been edited. One look at it and I am flabbergasted: onboard was the old gentleman gazing out the window, cigarette in hand.

Mu Xin travelled to England at the initiative and with the generous backing of Liu Dan, my old friend from Nanjing. Liu Dan had worked at the Jiangsu Academy of Chinese Painting. In 1981 he moved to the States, and befriended the English dealer of antiques and lover of Chinese ink painting, Hugh Moss. In 1992 I introduced Liu Dan to Mu Xin. From Moss’s manor where he later vacationed, Liu Dan wrote to me, saying he had lit a big whale oil candle from the sixteenth century to read books by Mu Xin. In 1993, Liu Dan and Moss had the idea of inviting Mu Xin for a visit. Mu Xin was then living in Jackson Heights. In spring 1994, the three of us sat in the front room of his small apartment, each smoking a cigarette, discussing the trip. Having booked for Mu Xin and me our flights to London, Liu Dan was to join Moss in England and await and welcome us there.

I knew, on that day, just how pleased and overjoyed Mu Xin was, ready to journey afar. The restrained look on his face, restrained from breaking into a smile, was too familiar to me. Can you think of any Chinese author, in whose poetry and prose Europe frequently features, who has yet never been there? Or of any old-school Shanghainese who has not longed for Britain? When a teenage Mu Xin arrived in Shanghai, the British and French concessions were still there; already he had known Byron and Hardy – and Shakespeare, needless to say – by heart.

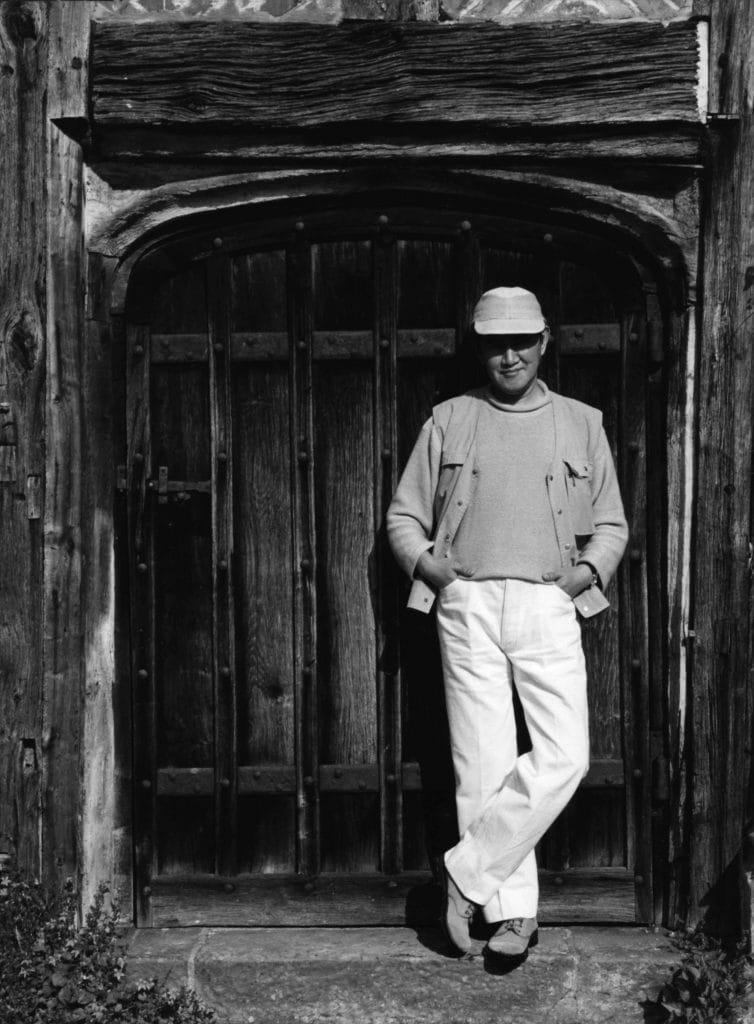

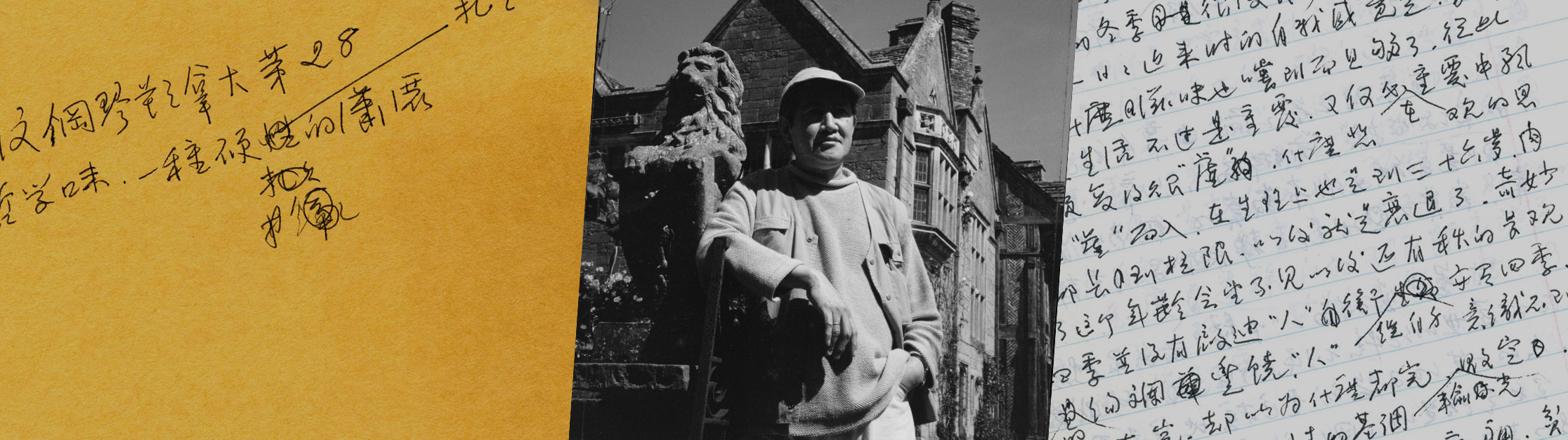

But Mu Xin, amidst our excited talks, always found a way to change the subject, jesting about this, chatting about that. What followed has been recounted in his unfinished manuscript ‘A Thousand and One Nights in England’. What I can continue to alternately tell is that we stayed for a total of three weeks in Moss’s old Tudor manor; a young French chef was hired to cook for us. Moss drove us to London for a three-day trip; we then visited Shakespeare’s Birthplace. Mu Xin and I routinely strolled around the manor surrounded by oak trees; or he stayed in his room until being asked by us to descend before dinner. After dinner everyone conversed. Once I made life drawings of English friends, whilst Moss took out his guitar and quietly sang…

I devour reminiscences of every kind about Lu Xun, who is said to never take any time off. Living for ten years in Shanghai, only once did he holiday for two or three days with Xu Guangping in Hangzhou; this was his only outing in his late years. Mu Xin was the same. For thirty years we were friends. Except for a day or two we spent leisurely at Harvard University, this trip was the only time when I saw him not at work, merrily on the loose. Arriving in New York aged fifty-five, treasuring every minute as gold and writing as though there were no tomorrow, Mu Xin may have been staying true to the literati ideal, all the while avenging his mature years squandered in prison and under surveillance. True enough, travelling around Europe is a luxury requiring plenty of spare cash. As far as I know, after settling in New York, Mu Xin visited but Boston and Washington D.C.; even his early decades in China were devoid of trips – and of plans for such trips – to famous mountains and rivers, and were marked only by a period of seclusion on Mount Mogan when he was young and by spells in Beijing and Harbin for work before he moved abroad.

In effect, it was to a cosmos on paper and to a world in books that Lu Xun or Mu Xin was accustomed. Real travels did not enthuse them. ‘What of “seeing is believing”?’, once scorned Mu Xin, ‘Having been to the pyramids and snatched a picture – that’s it? “Seeing is believing” is the philosophy of tourists.’ Each outing Mu Xin had – even taking the subway to Manhattan – was treated by him as a major event. Parties of all sorts, he avoided as many as was possible. I chided him, for a few times it had been his idea to go out in the first place. He laughed, and said it was rather like his mother and sister when, as a child he saw them busying themselves in front of the mirror for half a day – what to do with their hair, which dress to wear – before saying, all of a sudden, ‘I’m not going!’

Between Mu Xin’s England trip and his return to China in 2006, two of his closest friends, Zhang Xuelin and Huang Qiuhong, arranged several times for him to travel to France, Spain, Austria, and Russia. Mu Xin appeared to take it seriously, relating personalities and anecdotes of said countries, exultant. And yet, when the moment came to book tickets, ‘I’m not going!’ – as if sulking. I had then returned to China. Told of all this, I knew there was nothing to be done. In my conjecture, this was his dejection in old age: youthful yearnings had all but faded; time and opportunities, all lost. Travelling in Europe was for Mu Xin solemn and sacred; like fame arriving late, its taste had changed. As he wrote in a poem: ‘The day Pompeii is awarded me / Pompeii is already a wreck.’ Later, when his most becoming exhibition in his lifetime was held at Yale University Art Gallery, he did not attend the opening.

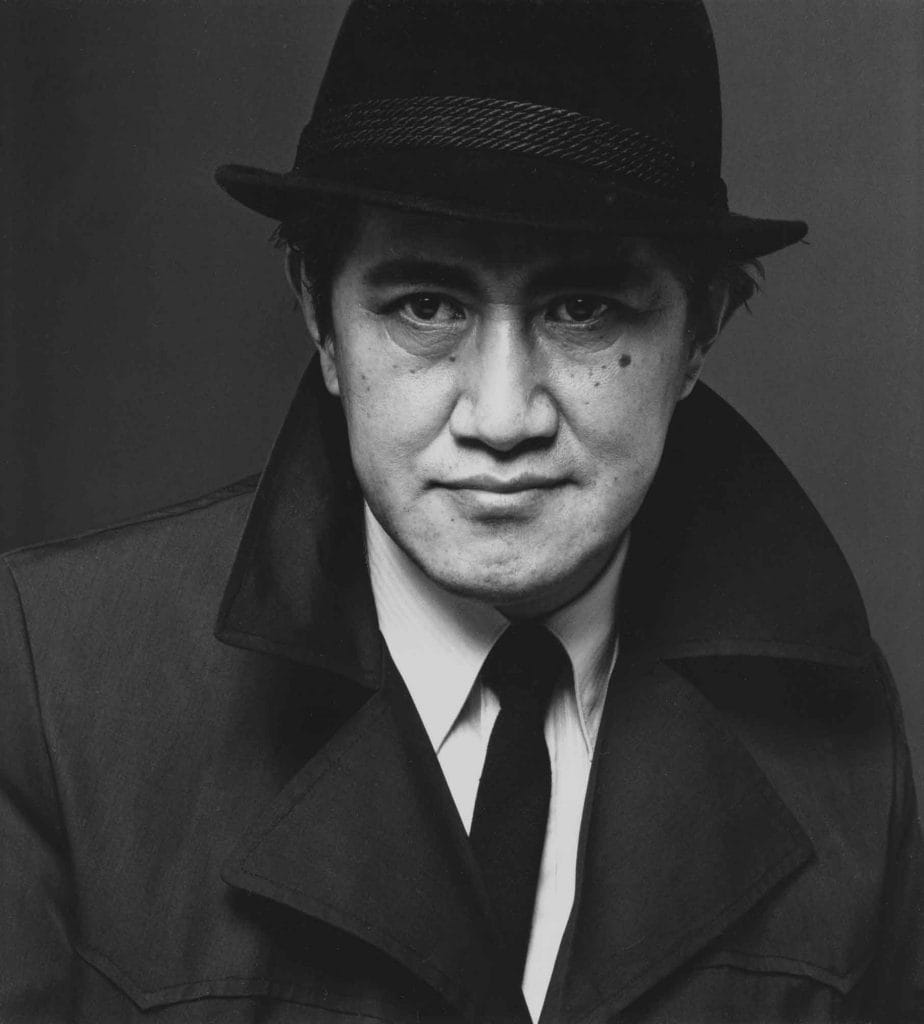

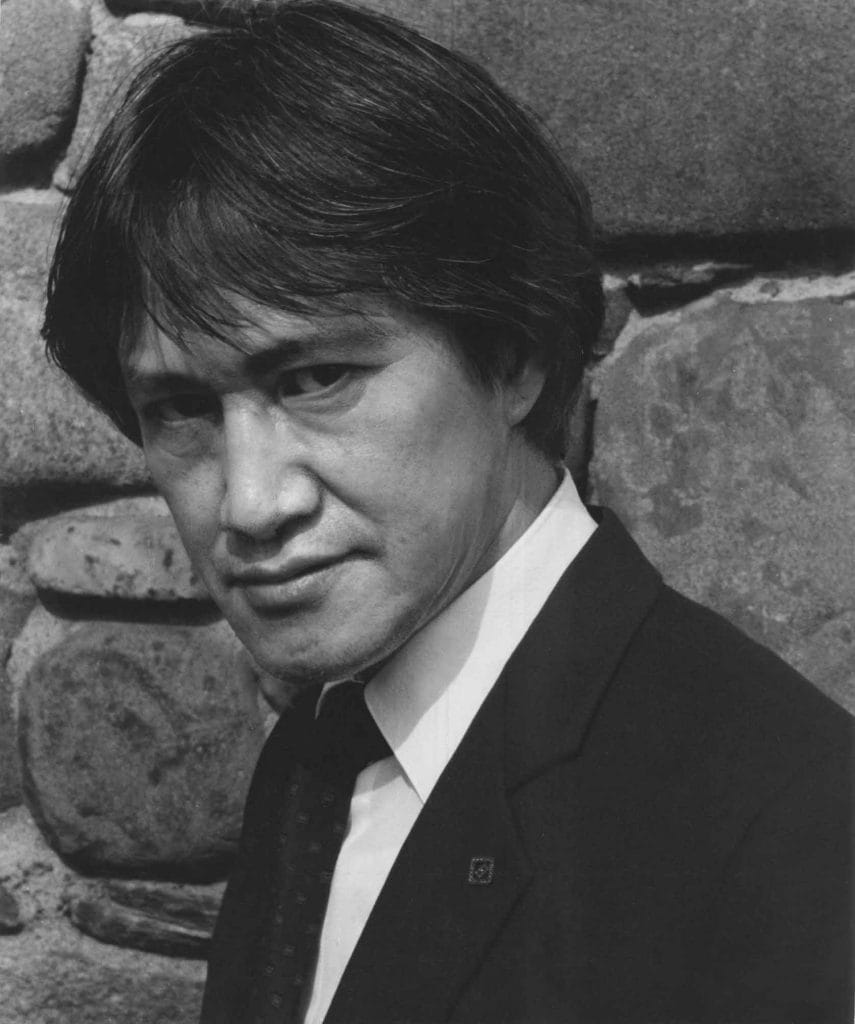

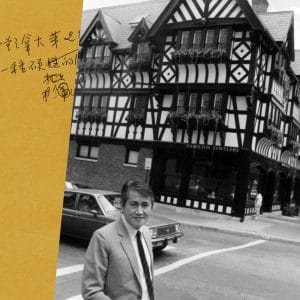

He grew up a quiet child. When the young gent had to go on a journey, he had to go in a manner befitting. He must go to Europe à la gentry of the past, much like what he had read, as an adolescent, in countless translated literature. The hospitality of Liu Dan and Hugh Moss was sufficiently befitting. Looking back, I see that it was in 1994, and only in 1994, that Mu Xin was convinced. Quietly he prepared his wardrobe – formal wear, casual wear, bowler hat, baseball cap, a beige linen vest that he altered himself – and off he went.

Accompanied by me, of course. No aged young gent goes on a journey unaccompanied; besides, I came perpetually armed with a video camera. I said, you move about as you like, don’t look at me, it’s recording now, and can be edited later. Ordinarily he refused to be filmed, but this time around he obeyed, smiling timidly like a child, looking eager. Fortunately he was in such a good mood. Apart from the documentary made of him in 2010 by two New York filmmakers, this is the only moving image of his everyday life. Aged sixty-seven that year, he appeared robust, and carried himself as a man in his prime.

Effectively, from beginning to end Mu Xin was the actor in his own voyage to England. With the slight nervousness known to whomever is conscious of being filmed, he gradually unfolded his elegant demeanour which he had quietly been training for a lifetime. We look at the video now and see this demeanour: that of an old man, moreover. When a man like Mu Xin ages, there is elegance.

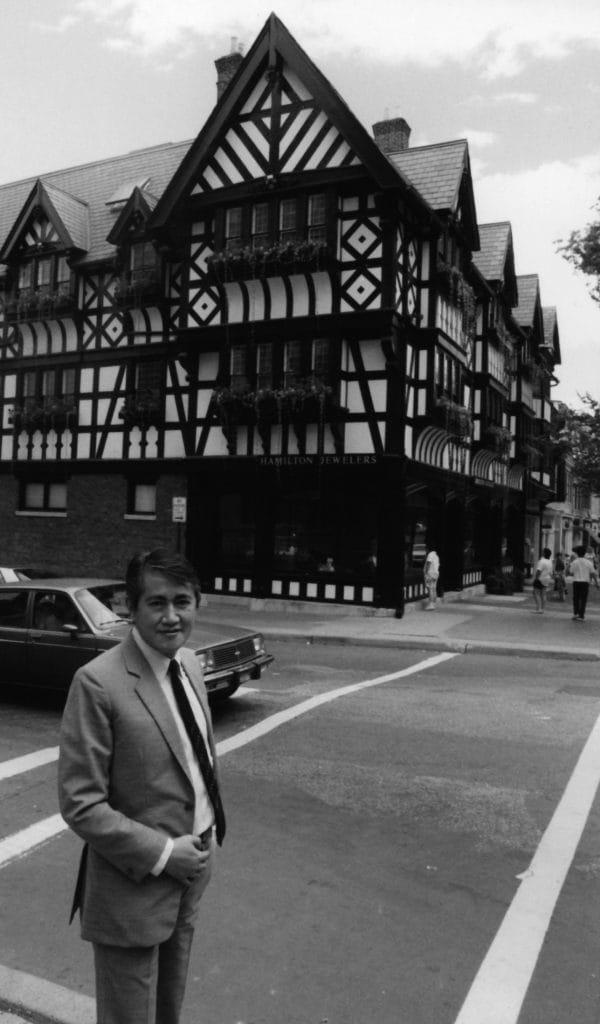

Nonetheless, as I had expected, he was seriously disappointed with England: postwar Europe, and former powers now approaching another fin du siècle, could no longer correspond to the nineteenth-century imagination that Mu Xin had transported from his early readings of translated literature. Though he travelled only to England, from Shakespeare to Wilde, his engrained British memory (including that of Laurence Olivier, by whom his generation had been fascinated in the 1950s) could not be attested by the England of 1994. ‘Common now, all too common now’, he muttered. At times he even got cross. Seeing in Westminster Abbey the tombs of the greats embedded in the marble floor, ceaselessly stepped upon by tourists, Mu Xin turned green: ‘Inconceivable!’, he said to me in a panic, ‘How can this be!’ He commended every corner of Moss’s manor, saying everything was ‘right’, but he could not comprehend why the wealthy Hugh Moss was dressed always in jeans and a shirt.

He wrote hundreds of poems about countries in Europe. I have not had a chance to discern if subtle changes manifested themselves in the Europe under his pen after his time in England. At the beginning of the new millennium, I recommended his complete oeuvre to Wolfgang Kubin, a German sinologist and translator of contemporary Chinese poetry. A year later, I saw Kubin again but did not ask if he had read any of it (this is the only thing I regret where Mu Xin is concerned). Instead Kubin asked me: ‘That Mu Xin of yours – he has been to Denmark?’

I do not recall if I told the truth. What I know is that the work of some dozens of Chinese writers and poets of my generation appeared in translation of multiple languages as early as the 1980s and 1990s; often they were invited to visit or to stay in England or France. Today, readers of Chinese literature in Europe and America still do not know who Mu Xin is. When Mr. Kubin asked after him, Mu Xin was nearly eighty. Now he has been dead for six years.

He has been dead for six years. Last year, in spring and summer, the BBC came twice to Wuzhen, making as part of the new Civilisation series Mu Xin’s transfer painting as entry into Chinese shanshui. This year, researchers from the British Library were in Wuzhen several times; in October, they brought the manuscripts of Byron, Lamb, Wilde, and Woolf to the Mu Xin Museum.

‘Inconceivable! How can this be!’ I see Mu Xin’s panic-stricken face in Westminster Abbey. It is, to be precise, in the video I made that I see Mu Xin, walking through the streets of London, head held high, white hair ruffled by the wind. A child from Wuzhen.

Details of this trip have frankly all but escaped me. Two episodes, however, stay as though they took place only yesterday. The day before we left England, Mu Xin took out his savings, and asked me to accompany him to an antique shop near the manor. Whenever he was about to make a mildly excessive purchase, he was particularly serene. On this day he was a docile child, as if I were the parent, taking him to buy sweets. We arrived in the shop. He looked, picked a platinum ring, a pair of cufflinks and some other things, and paid without saying a word. I thought of my mother, who too came from Zhejiang, and who too had extravagant inclinations and a frugal disposition, neither of which she ever uttered. Keeping in mind (maybe for years, maybe for decades) a few things she considered worth having, when finally deciding upon an acquisition, she did so with no hesitation, nor negotiation; quietly she paid for it, then stashed it away. Shanghainese people who came from the Republican era, and who had origins in the regions of Jiangsu and Zhejiang had, since always, been acquainted with things British.

Thereupon Mu Xin wore this ring often. But I never saw him with the cufflinks. Could he have been saving them for the opening of a future exhibition of his? At the end of 2011 he was dying. In a state of delirium he said: ‘When you give speeches… wear the cufflinks… raise your hand… if people see them, you say… they are a present from me.’ I had forgotten these words by the time I went through his remnants, and encountered in a small box these cufflinks. In accordance also with my mother’s way of keeping precious little items, this box was wrapped in a handkerchief.

The other episode came from the day after we arrived – ah, the best moments of a journey come always at the inception of one’s arrival. Overcast. Daybreak. Out of the manor we walked slowly toward the field next to a forest. The air was moist, and the verdant green of early summer everywhere. Now and then, through the trees sounded horses’ neighs, crisp and clear. Mu Xin stopped, and turned to me, taking out a cigarette: ‘Ah, it’s been long since I heard a horse neigh…’ Visibly touched, he listened intently, and in a sudden tremor asked: ‘Have you read this one by Ouyang Xiu? I liked it as a child. I remember it still.’

Then he looked away, fixing his gaze somewhere in the forest. With an almost dull-witted look of concentration for a mental rehearsal before recitation, and with a touch of shyness, at last he resolved to repeat from memory, without lapse and without pause:

A wander through a midspring meadow

Horses neigh, the wind gentle

…

Twenty-three years have passed. I remember his frail voice, and the two of us standing between dew and mud in England. As for the verse, I recall now only the opening lines.

17 December 2017

Translated by: Dr. Hu Mingyuan

The text in the article is © Chen Danqing.

撰稿人: Chen Danqing

Chen Danqing was born in August 1953 in Shanghai. From 1970 to 1977, he taught himself how to paint when he was resettled to the countryside of Jiangxi and Jiangsu provinces. In 1978, he was enrolled in the Department of Oil Painting in China Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, and attended the first postgraduate class since the Cultural Revolution. He completed his graduation work, The Tibetan Series, in 1980. Between 1980 and 1981, he took a role as a lecturer in the First Studio in the Department of Oil Painting in the Academy. At the beginning of 1982, he self-funded further study in New York while working as a freelance painter. While in New York City, he studied under Mu Xin. In January 2000, he accepted a position from the Academy of Arts & Design at Tsinghua University and returned to China to teach. He resigned in 2006 to focus on his own artistic practice and rejoined the Academy in 2010. He was appointed Director of the Muxin Art Museum in 2014.