The creation of the police and the rise of detective fiction

Judith Flanders explores how the creation of a unified Metropolitan Police force in 1829 led to the birth of the fictional detective.

It’s easy to assume that there have always been police forces, but in reality, the idea is very new. Before the establishment of the police, governments called on the army to control rioting mobs and quell uprisings, but there was no civil force to prevent crime, or to detect it.

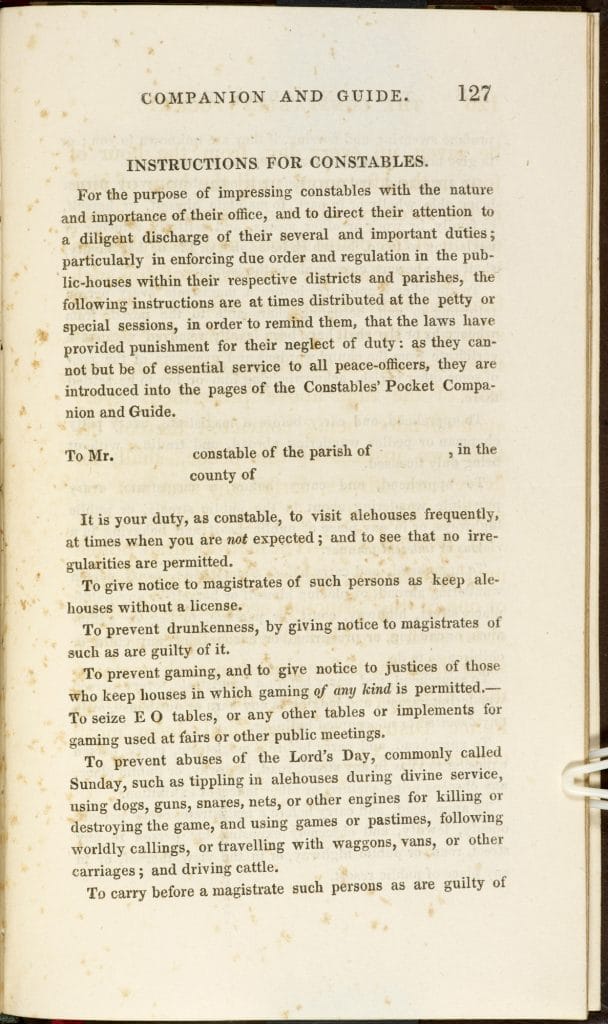

By the end of the 18th century in London, crime prevention was the responsibility of around 2,000 men, all employed by different parishes, local divisions or magistrates’ courts. It took a series of worrying current events to change this: the end of the French revolutionary wars saw the return of large numbers of suddenly unemployed soldiers hardened to scenes of violence and death. In addition, high food prices and chronic unemployment produced ever more incidents of civic unrest. In 1812 a parliamentary select committee recommended putting a single centralised authority in control of policing throughout London, but it took another 17 years to achieve this.

Blue coats and detective work

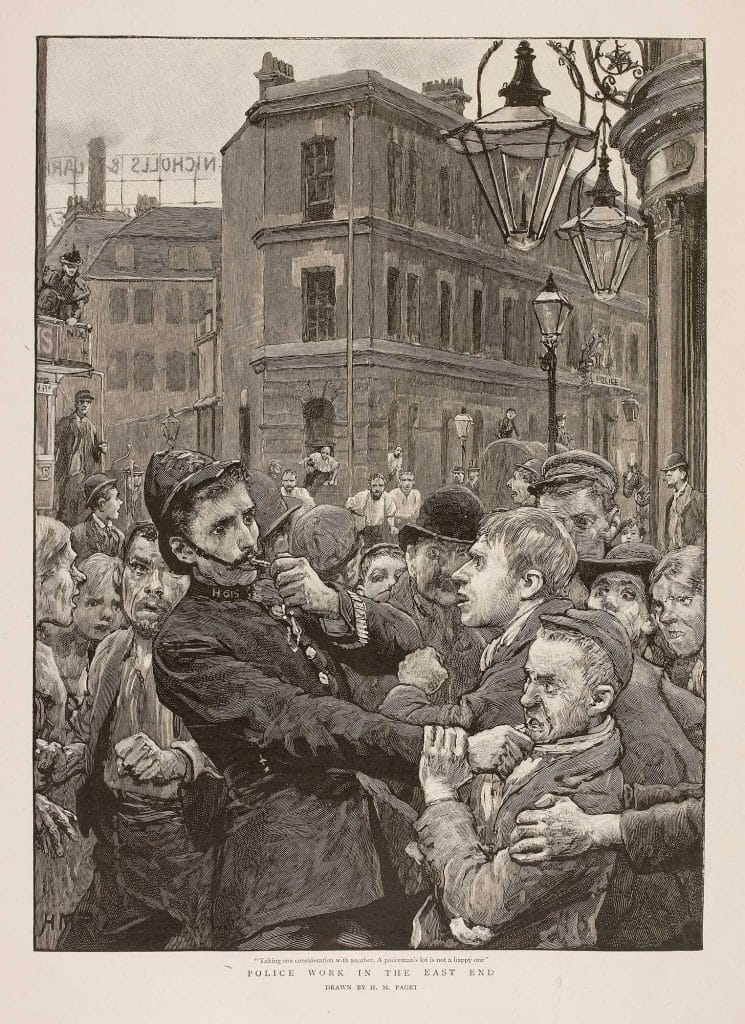

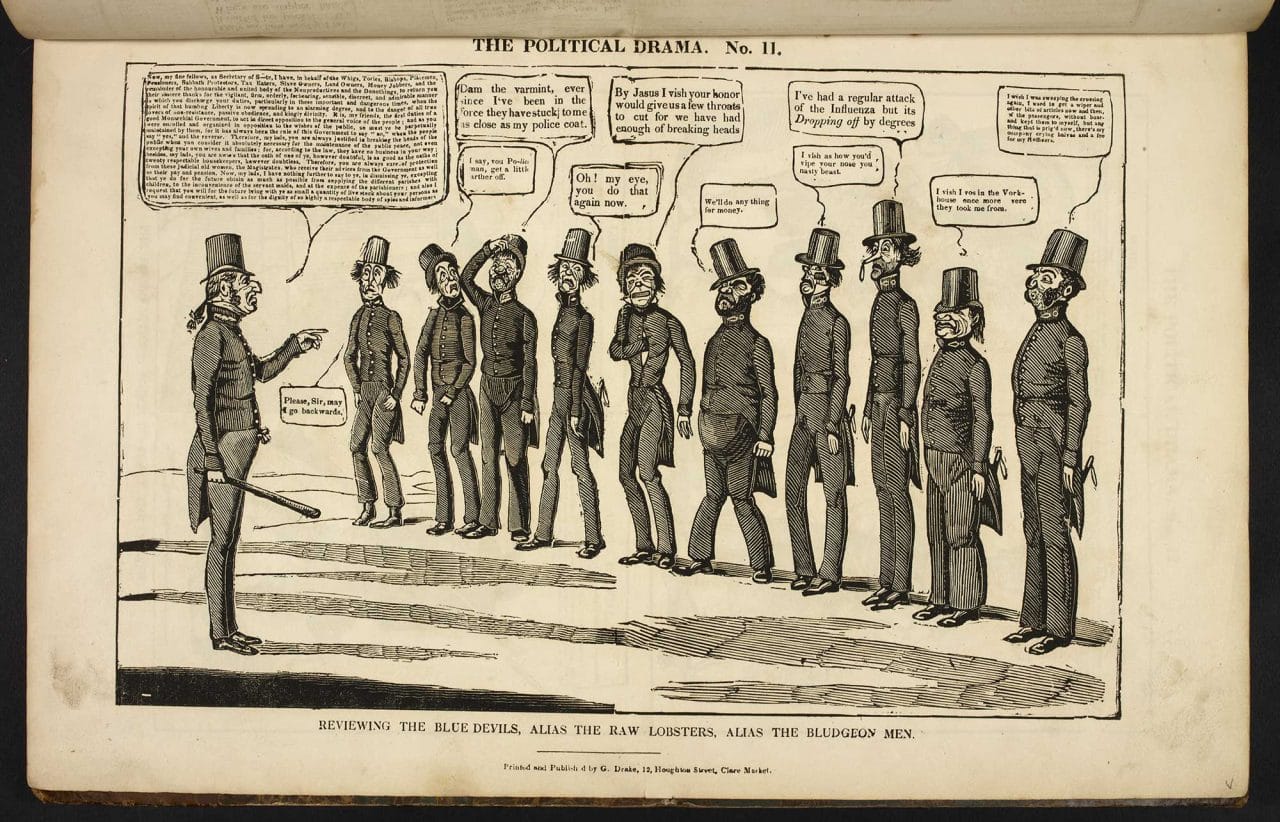

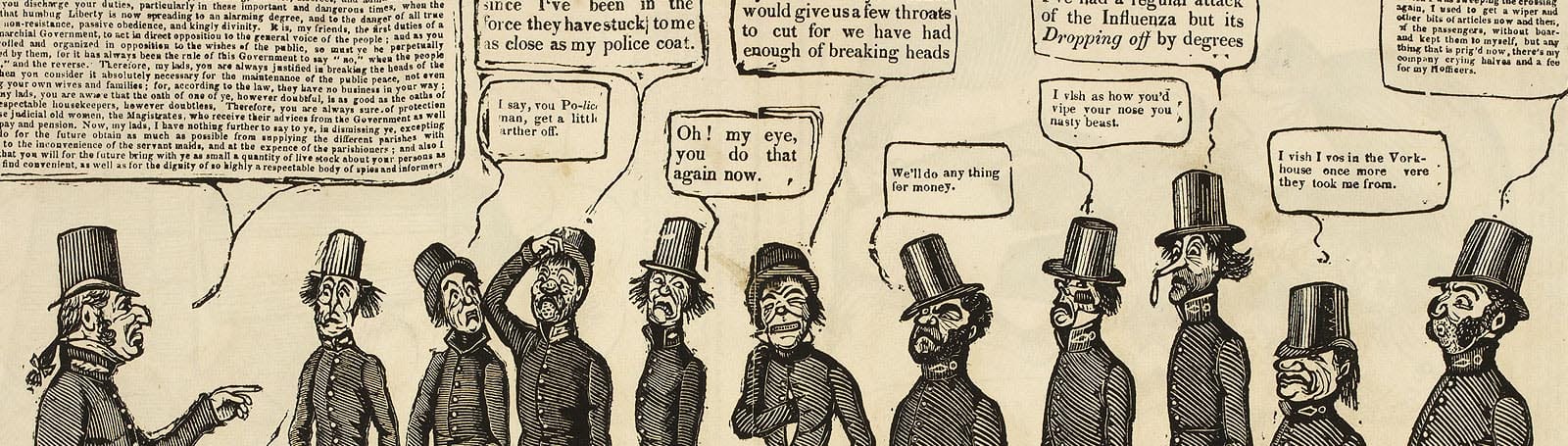

Thus on 29 September 1829, parishes within 12 miles of Charing Cross saw the first ‘new police’ on the streets. Within eight months there were 3,200 men, all dressed in blue, the colour chosen to reassure the population that, unlike the red-coated army, this was a civil, not a military force. (Not that the new colour made much difference: the police were tauntingly called ‘raw lobsters’ or ‘the unboiled’. An unboiled lobster is blue; when it is put in hot water it turns red. So a policeman was only ‘hot water’ away from being a soldier.)

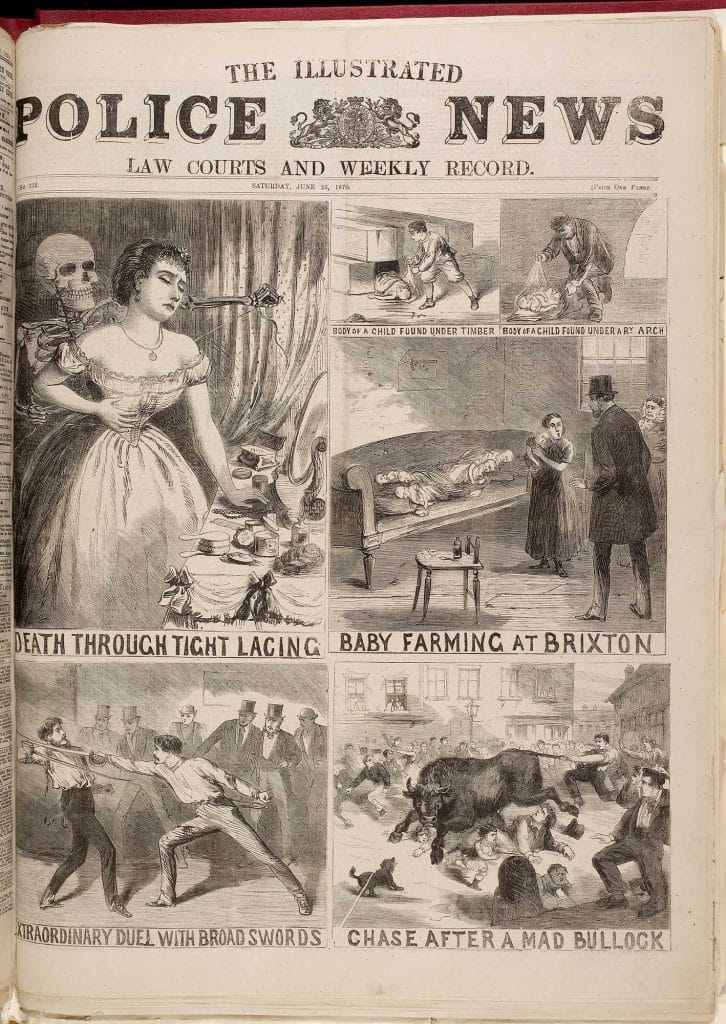

Until 1842, the police force was entirely dedicated to crime prevention. It was only when they took an embarrassingly long 10 days to find a murderer that it became clear they needed to focus on detection too, and the government opened an eight-man ‘Detective Department’. (Scotland Yard, a turning near Whitehall, was the address of police headquarters; soon it became shorthand for the Detective Department, renamed the Criminal Investigation Department, or CID, in 1878.) Police work was now about both the prevention of future crimes and the detection of past ones.

The first fictional detectives

Charles Dickens was enthralled by this idea, and wrote several articles praising the new department . Shortly afterwards, in his novel Bleak House (1852–3), Dickens created Mr Bucket, who has been called the first fictional detective, and, it is generally accepted, was drawn from the mannerisms and appearance of a real detective-inspector, Charles Field. What then seemed like a trick ending, where readers learn what the detective had been thinking all along, and thereby discover the murderer, appeared here for the first time. With this new twist, readers became fascinated, not by the crime itself, but by its solution.

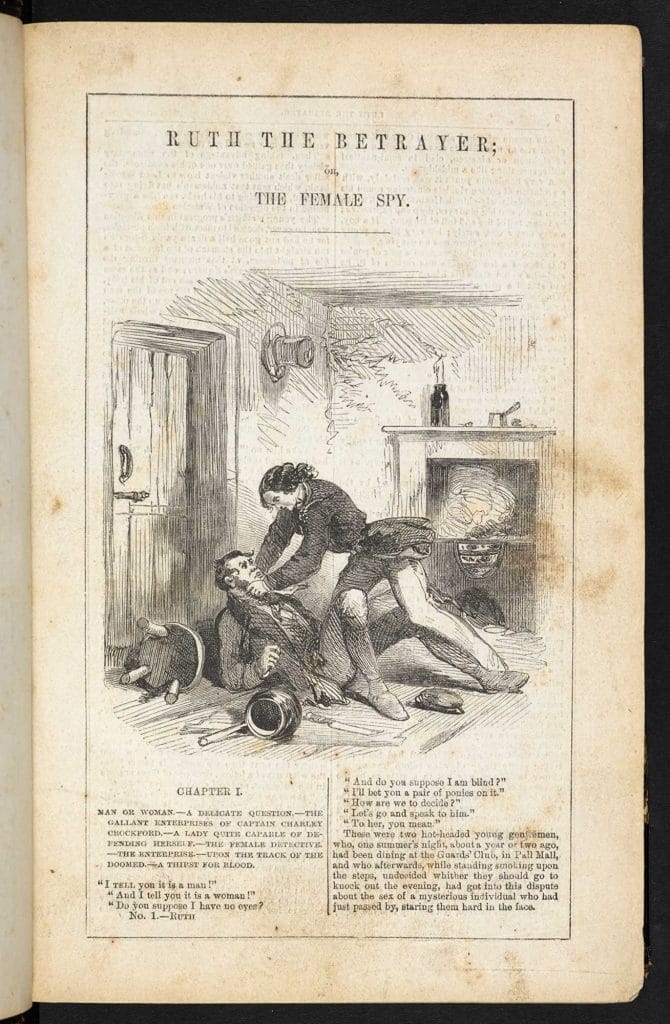

To satisfy this desire to explore how a crime is solved, dozens of stories with detective heroes began to appear. What is often called the first detective novel, The Moonstone, by Wilkie Collins, was published in 1868. But several years before that, the female professional detective in fiction had already been born, even though in the real world the police force was entirely male until two women were hired to look after female prisoners at police stations in 1883. In Ruth the Betrayer (first published in parts in 1862–3), Ruth Trail is ‘a female detective – a sort of spy we use in the hanky-panky way when a man would be too clumsy’. She is not of the regular police, but ‘attached to a notorious Secret Intelligence Office, established by an ex-member of the police force’. (Rather wonderfully, it is so secret that the office has a brass plaque on the door: ‘Secret Agent’, it reads.)

Public response to detective stories

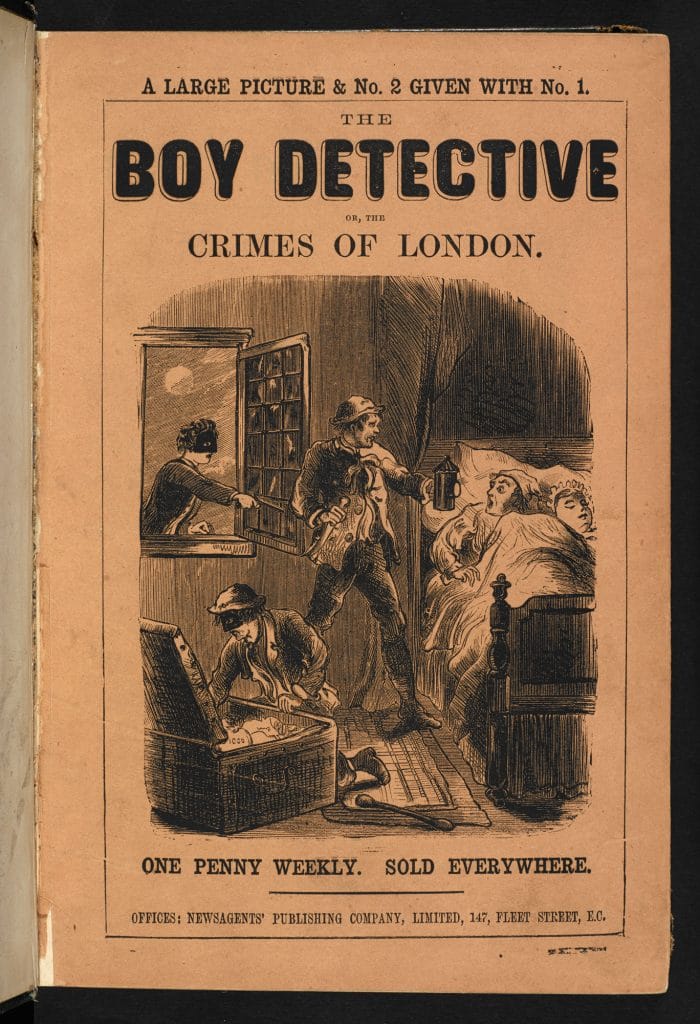

Working-class readers were initially ambivalent about fictional detectives, just as they were about the real police, whom they felt, possibly correctly, were only there to protect the middle-classes. Ruth the Betrayer was the heroine, but as a detective she was ‘degraded by the hateful calling of spy and informer’. A more middle-class heroine appeared a couple of years later, in Andrew Forrester’s Revelations of a Female Detective, and she fought back: ‘we detectives are necessary,’ she said. And slowly the working class came to agree – at least some of the time. In The Boy Detective Ernest Keen ‘could use dissimulation as a shield or sword when dealing with powerful enemies. In common life such conduct would be detestable, but Ernest Keen was the BOY DETECTIVE … in his own character there was not a franker, more impulsive lad in the world.’

The Boy Detective was also one of the earliest penny-dreadfuls to teach readers how to detect vicariously, explaining how clues were found, how one must not walk over ground where there might be footprints, how to check for bloodstains and more. In fact, in the early days of detection, it’s probably safe to say that detectives learned how to behave from Dickens’s Inspector Bucket, or Wilkie Collins’s Sergeant Cuff, every bit as much as the authors learned how to detect from the police.

The text in the article is © Judith Flanders. It may not be reproduced without permission.

撰稿人: Judith Flanders

Judith Flanders is a historian and author who focusses on the Victorian period. Her most recent book The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens’ London was published in 2012.