The figure of the governess

From Jane Eyre to Vanity Fair, the governess is a familiar figure in Victorian literature. She is also a strange one: not part of the family, yet not quite an ordinary servant. Kathryn Hughes focuses on the role and status of the governess in 19th century society.

The governess was one of the most familiar figures in mid-Victorian life and literature. The 1851 Census revealed that 25,000 women earned their living teaching and caring for other women’s children. Most governesses lived with their employers and were paid a small salary on top of their board and lodging.

From the 1840s novelists started to put governesses into their fiction, usually as heroines but sometimes as villains. In 1847 Charlotte Brontë published Jane Eyre, the story of a governess who eventually marries her employer, the brooding Mr Rochester. The same year William Thackeray started publishing instalments of Vanity Fair, in which a scheming young governess called Becky Sharp lies and cheats her way through Regency high society

Who became a governess?

The first part of the 19th century was marked by deep economic distress. A series of bank failures during and after the Napoleonic Wars, combined with no Welfare State, meant that many middle-class families found themselves destitute overnight. Young men from good homes could leave school and go out to work from the age of 15 without being ashamed. There was always a chance that they would earn back their family’s fortune. But their sisters, educated to be ‘ladies’, would have felt humiliated to be seen serving in a shop or working in a factory alongside working-class girls. The only possibility open to them was to get a job as a teacher, either in a small girls’ school or in someone else’s home.

Who employed a governess?

The upper classes had employed governesses for centuries. But from the beginning of the 19th century the wealthier sections of the middle classes followed suit. Employing a governess sent a signal that the lady of the house was too ‘genteel’ to teach her daughters herself. Just as she employed servants to clean her house, she paid another woman to raise her children. Hiring a governess became a status symbol.

What did the governess teach?

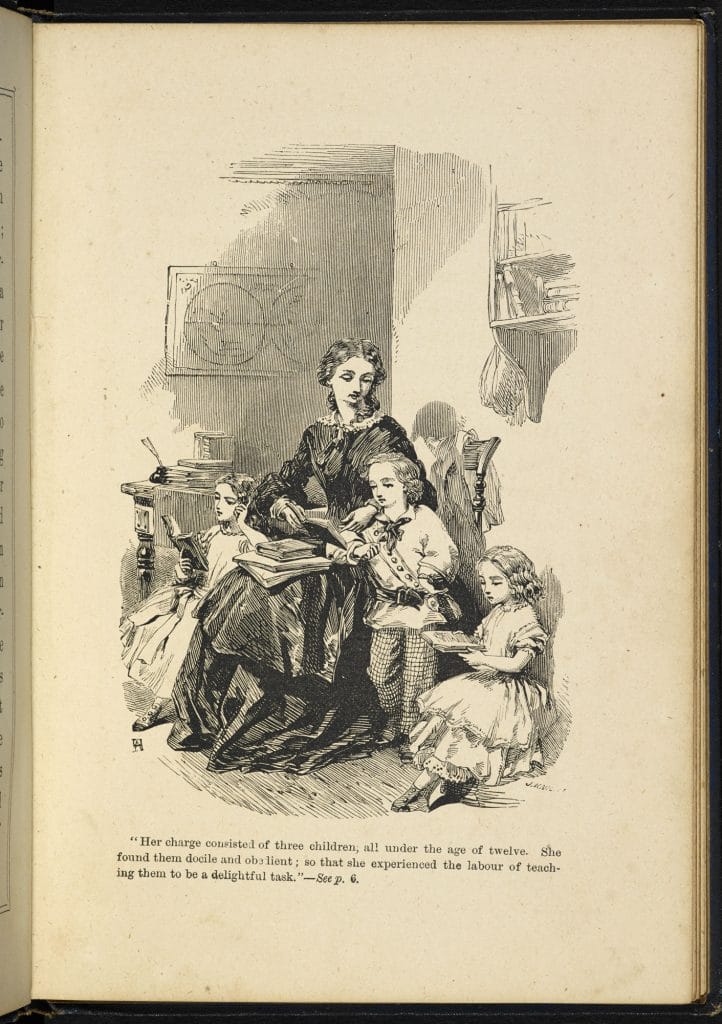

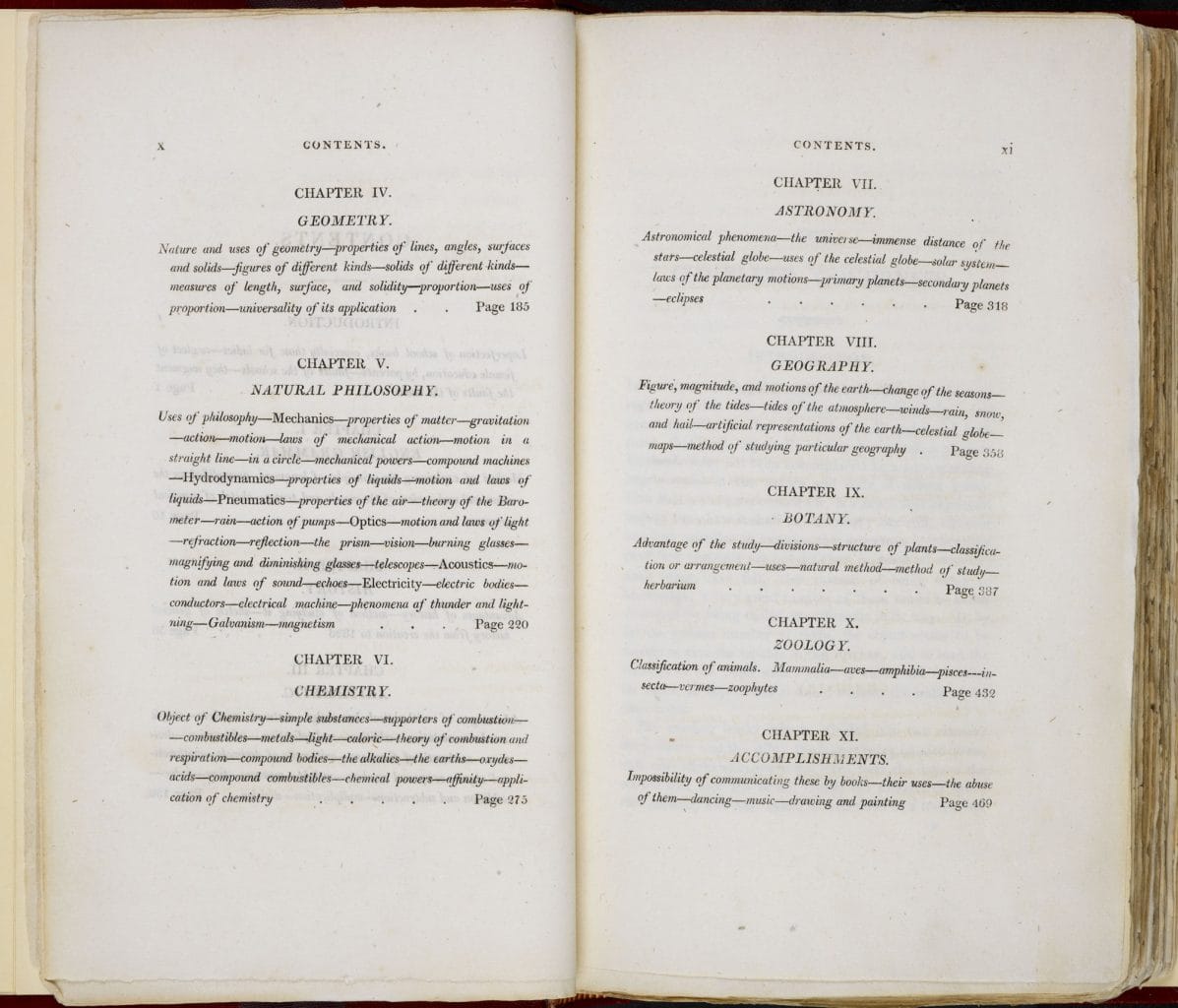

Depending on the age of her pupils, the governess could find herself teaching ‘the three Rs’ (reading, writing and arithmetic) to the youngest, while coaching the older girls in French conversation, history and ‘Use of the Globes’ or Geography. If her pupils were older teens, the governess would also be expected to instruct them in key ‘accomplishments’ such as drawing, playing piano, dancing and deportment (ie how to conduct oneself properly), all designed to attract an eligible suitor in a very crowded marriage market. The governess might also be in charge of small boys up to the age of eight, before they were sent away to school. The governess was expected to look after her pupils’ moral education too. As well as reading the Bible and saying prayers with them, she was to set a good example of modest, moral behaviour. For that reason, employers put great emphasis on hiring a governess who shared their religious affiliation – Church of England, Methodist or Baptist. Although French governesses were admired for their ability to teach a correct accent, most families would not consider employing a Roman Catholic.

The outsider

Life was full of social and emotional tensions for the governess since she didn’t quite fit anywhere. She was a surrogate mother who had no children of her own, a family member who was sometimes mistaken for a servant. Was she socially equal or inferior to her employers? If the family had only recently stepped up the social scale, perhaps she’d consider herself superior. She was rarely invited to sit down to dinner with her employers, even if they were kind. The servants disliked the governess because they were expected to be deferential towards her, despite the fact that she had to go out to work, just like them. One governess, known only as SSH, recalled how, sitting down to dinner for the first time in a new job , she was overwhelmed by a ‘sense of friendlessness and isolation’ when she noticed herself pointedly served after the ladies of the house.

The governess often spent the evenings alone and she was sometimes expected to use the schoolroom as her sitting ro om. Life could feel very lonely: 19 year old Edith Gates, a governess in Reading in the 1870s, confides to her diary how homesick she feels. 30 years earlier Charlotte Brontë tried to avoid going into her employers’ sitting room in the evenings because she found it awkward to make conversation with people she didn’t know very well.

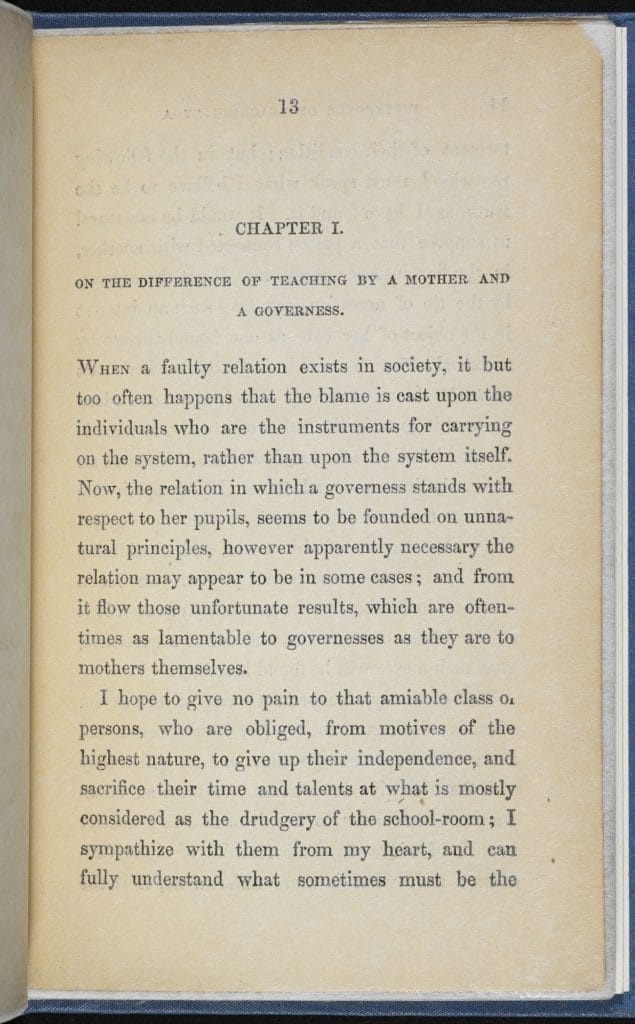

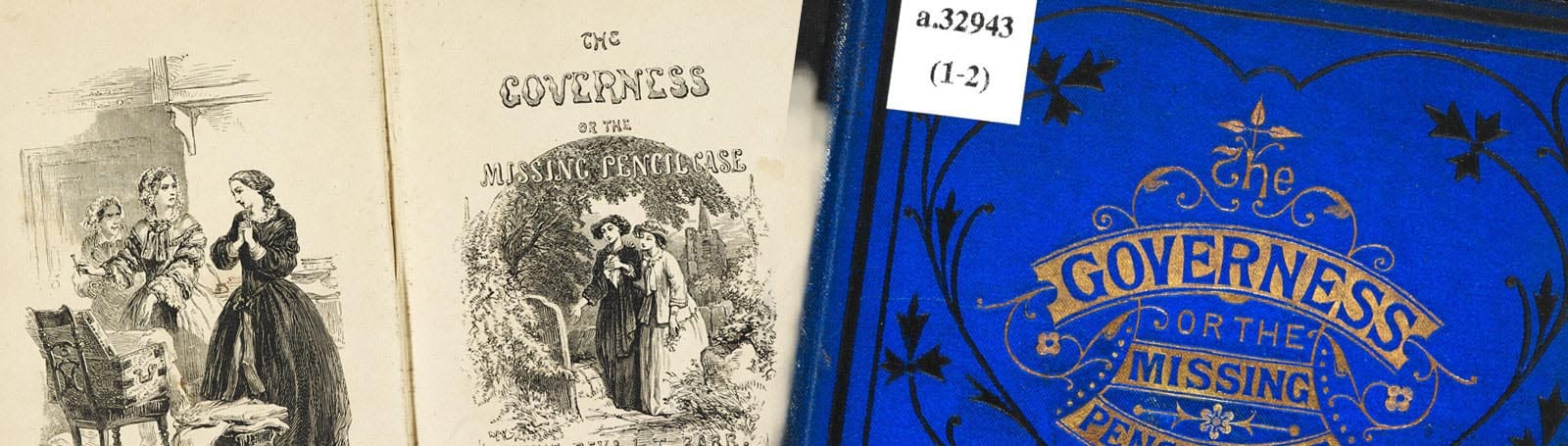

Getting married was one way that the governess might be able to leave her job. But it was hard for her to meet suitable men. Female employers often worried that the governess might try to marry one of the young gentlemen of the house. For that reason, advice books aimed at employers recommended employing a plain governess. There were many similar books aimed at the governess too, telling her what to teach and how to manage the relationship with her employers. These had titles like ‘Mothers and Governesses’ and The Complete Governess; a course of mental instruction for ladies.

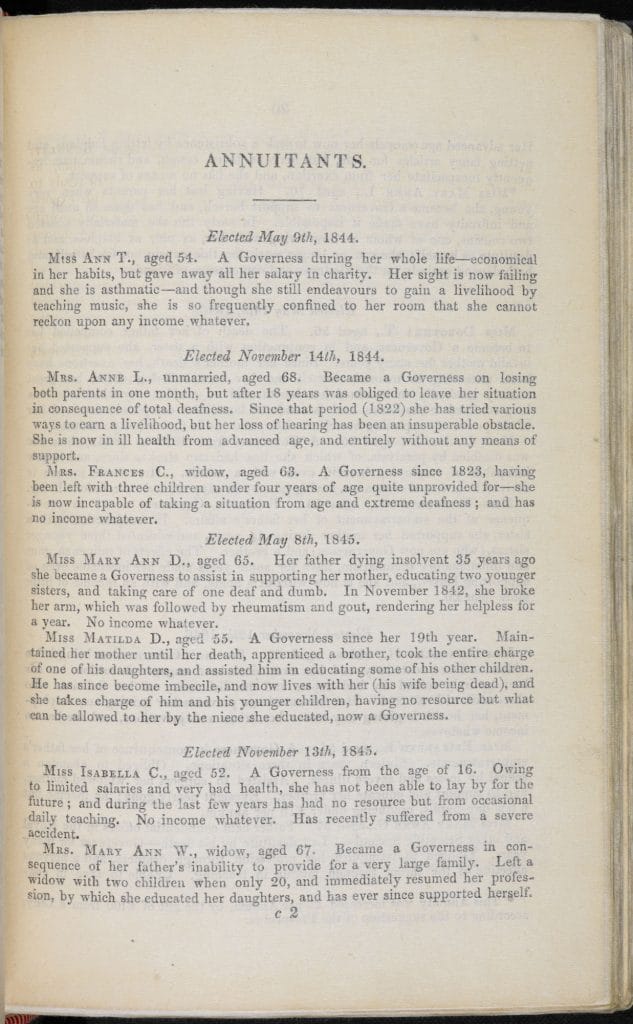

Most employers only needed the services of a governess for a few years which meant that she frequently found herself having to look for a new situation. Since salaries were so low, there was little chance of saving for illness or retirement. Many governesses found themselves facing poverty in middle age. In 1841 The Governesses’ Benevolent Institution was set up to help some of them with pensions.

Governesses in fiction

When Victorian authors wanted to write a novel about a young woman, it made sense for her to be a governess. Just like an orphan, the governess had to make her own way in the world, travelling alone far from home, with no resources to call upon if things went wrong. Her status as a ‘lady’ allowed her to mix in the best circles, but the fact that she worked meant that she also encountered all sorts of people and situations that would have been far-fetched for a girl who lived with her parents. The governess was a blank slate onto which all possibilities were open, so that novelists could write any plot that they wanted. Charlotte and Anne Brontë, who both published novels with governess heroines, used their real-life experiences of the schoolroom. Other writers, like William Thackeray, drew on stories circulating about scheming governesses who disliked their pupils and were desperate to get on in the world by marrying into their employers’ family.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Kathryn Hughes

Kathryn Hughes is Professor of Lifewriting and Convenor of the MA in Lifewriting at the University of East Anglia. Her first book The Victorian Governess was based on her PhD in Victorian History. Kathryn is also editor of George Eliot: A Family History and has won many national prizes for her journalism and historical writing. She is a contributing editor to Prospect magazine as well as a book reviewer and commentator for the Guardian and BBC Radio.