The history of women’s football in the UK

Although women have likely played football for as long as the game has existed, in the UK there has long been resistance to women’s football. Explore the beginnings of the game and the efforts of women rallying for the right to play.

The early years of women’s football

Early direct references to women playing football in the UK suggest it has long been well established, with accounts from the late 18th century describing annual football matches involving the fisherwomen of Musselburgh and Inveresk in East Lothian.[1] Such descriptions show women engaging in football in an informal manner, much the same as men were doing in that period.

In the 19th century, Association football was established in England; the rules of the game were standardised, allowing clubs to play each other without disagreements arising as to what was and was not allowed. Subsequently, by the late 1800s, due to the popularity of this form of football, women too sought to establish women’s teams and leagues in the same way as men had done.

However, resistance to women’s football grew. Much like other aspects of women’s liberation some progress had been accepted as the hobbies of wealthy women, but any effort to establish women’s football as a regulated, potentially even monetised, sport faced rejection.

The first organised women’s football teams

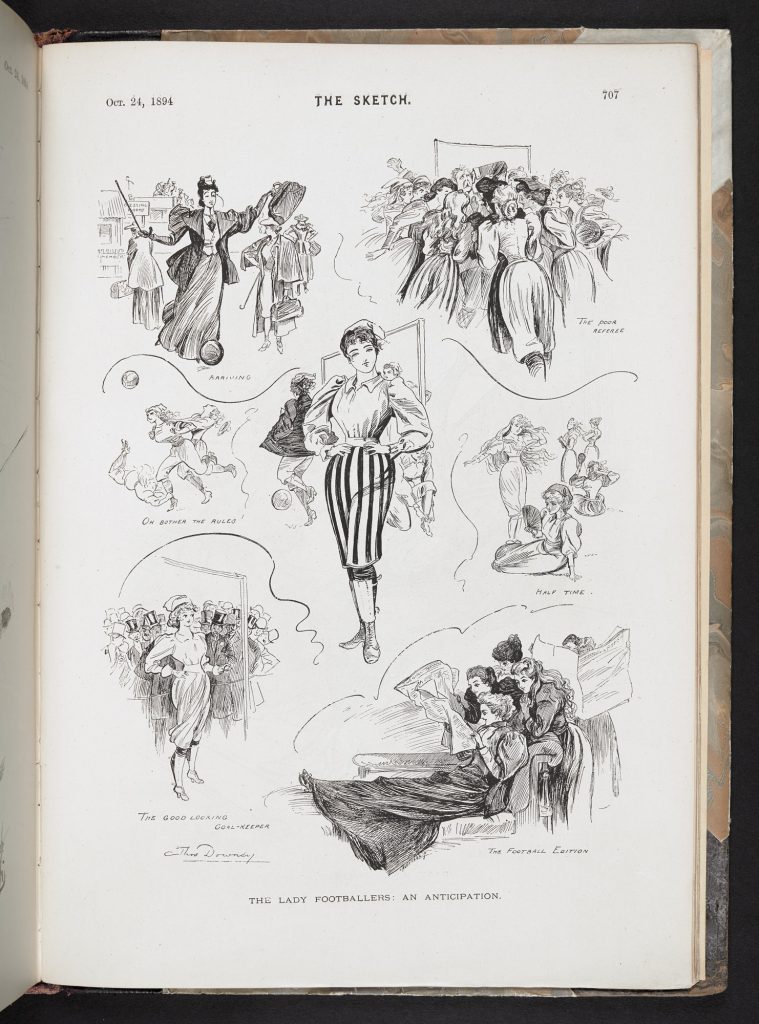

This struggle is reflected in the efforts of two of the first established women’s football teams during the 1880s and 1890s. Press coverage was brutal and contemptuous; it focussed on the women’s appearance, their dress and their bodies, setting the precedent for how women’s football would be discussed for generations. In essence, football was a rough men’s game, infinitely unsuitable for women.

Whether or not it has been the working mans’ religion or linked to proletarian community life, it has clearly mattered to many people that football, whatever the code, should be synonymous with masculinity.[2]

The first of these teams, widely considered the first British women’s football team, was Mrs Graham’s XI, established in Scotland in 1881 by Helen Graham Matthews (who played under the pseudonym Mrs Graham). The team’s first recorded match was on 9 May 1881 at Edinburgh’s Easter Road Stadium. At a match a week later play was called off after a protest at women playing resulted in a violent pitch invasion. Pitch invasions continued at matches, hampering play. Eventually, this early attempt to establish women’s league football was abandoned.

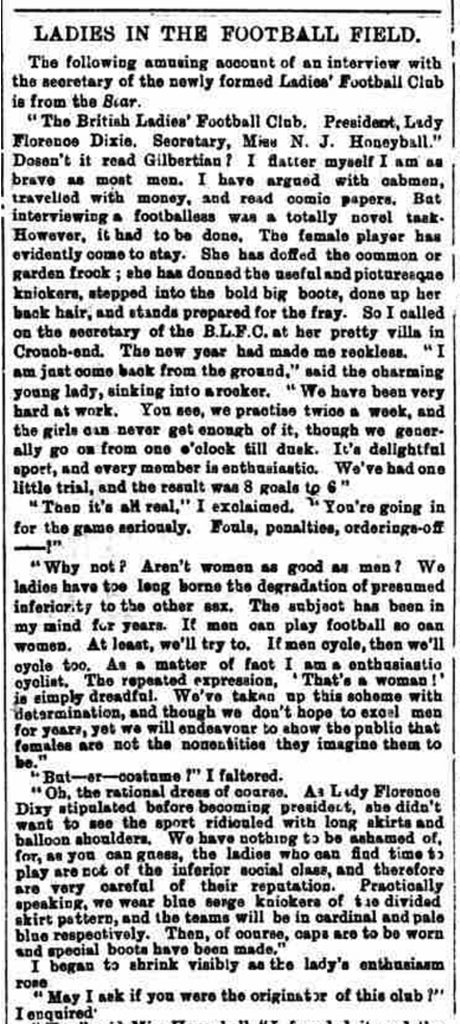

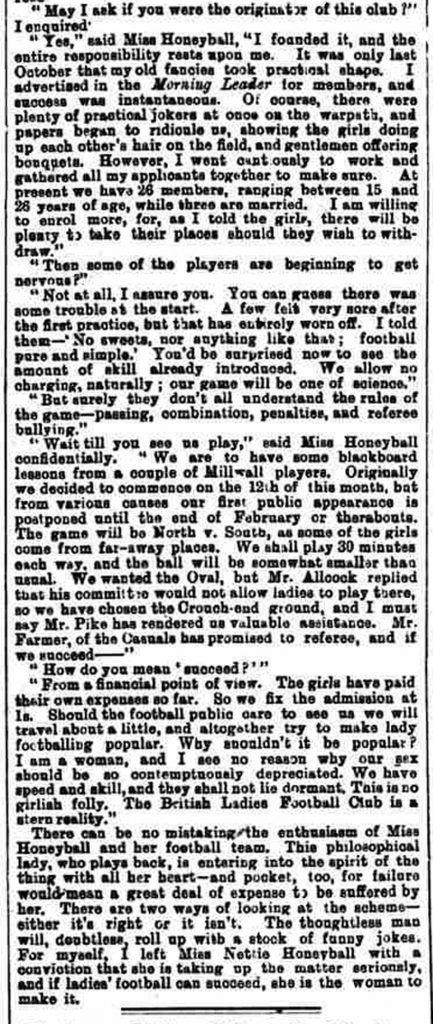

The second team, the British Ladies Football Club, was formed around 1894 by Alfred Hewitt Smith, with Nettie Honeyball (another pseudonym) as captain and figurehead. Under the patronage of Lady Florence Dixie, the Scottish writer and feminist, the team was joined by Helen Matthews of Mrs Graham’s XI.

In 1894, Honeyball advertised the team publicly, issuing a call-out for players. Asked about her motives for establishing the team she responded:

Why not? Aren’t women as good as men? We ladies have too long borne the degredation of presumed inferiority to the other sex. The subject has been in my mind for years. If men can play football so can women.[3]

Many were unconvinced. Even before the team had played one match they were reported on with derision. Though some considered the idea curious and amusing rather than threatening, there were commonalitites in the critiques, including:

- The unsuitability of the sport for women’s bodies. Many considered it damaging and dangerous to women’s health.

- Propriety, given that for practical reasons women would need to wear Rational Dress to play.

- The uncomfortable idea that women might even charge for tickets and thus make money from sport.

- Lastly, underpininning it all but harder to isolate, the concept that football was the ‘Great British Game for Men’, intrinsically linked to masculinity and threatened by female encroachment.

Many contemporary reports begin by listing the first three reasons above before ending on a sentiment that belies the strong feeling behind the final point:

It is a great game, and a manly game, and deservedly popular. It must not, however, be forgotten that it was originated and improved by strong young men, and only by strong young men can it with any safety be regularly played.[4]

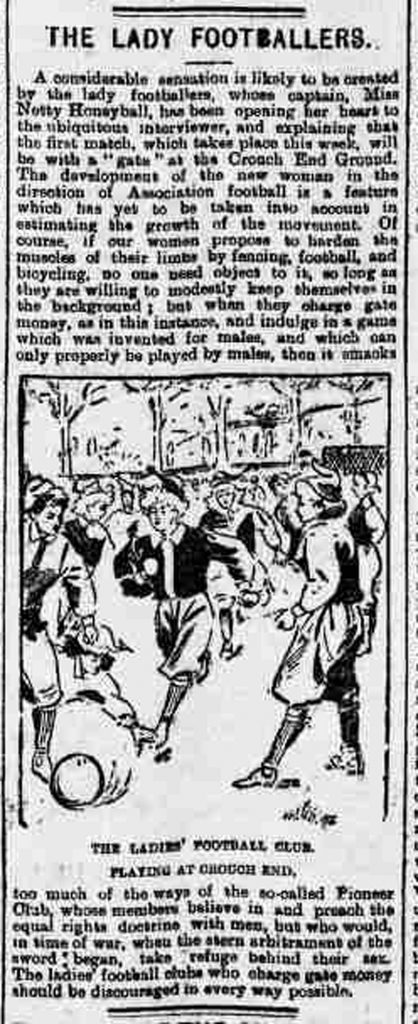

Despite the negative reaction, Honeyball announced that the BLFC would be playing a public match in 1895. Much of the outrage was focussed on the team’s decision to charge for tickets:

The development of the new woman in the direction of Association Football is a feature which has yet to be taken into account in estimating the growth of the movement. Of course, if our women propose to harden the muscles of their limbs by fencing, football, and bicycling, no one need object to it, so long as they are willing to modestly keep themselves in the background; but when they charge gate money, as in this instance, and indulge in a game which was invented for males, and which can only properly be played by males, then it smacks too much of the ways of the so-called Pioneer Club,[5] whose members believe in and preach the equal rights doctrine with men, but who would, in time of war, when the stern arbitrament of the sword began, take refuge behind their sex.[6]

The match went ahead near Alexandria Palace in London on 25 March 1895. The BLFC divided themselves into two teams and played under the names ‘North’ and ‘South’. North won 7–1.

Around 10,000 people attended the match, with thousands more turned away at the gate. Press reports were disparaging: the play was poor, the women looked ridiculous in their ‘costumes’ and apparently most of the crowd left at half-time bored. The undoubted bias in reporting makes it hard to establish much else. Most reports focussed on the unsuitability of the sport for women’s bodies and the shock at them appearing in Rational Dress.

What is evident is that Honeyball’s own accounts of the team, of their frequent gruelling practices – they were trained by professional Millwall players – is clearly at odds to the descriptions of the match, half of which claim the women didn’t even know the rules of the game. ‘We have been very hard at work. You see, we practise twice a week, and the girls can never get enough of it, though we generally go on from one o’clock until dark.’[7]

Honeyball attempted to keep the team going but without support, interest faded. At the same time, men’s football was quickly becoming the most popular sport in the world.

Association football: Early 20th century

Around 20 years later, women’s football saw a dramatic resurgence, reaching a popularity that was only dreamt of a generation before – but the same prejudices against it soon re-emerged.

Women working in factories during the First World War, largely in Northern English and Scottish towns, played football on their breaks and began to form teams. Local interest grew, and fixtures were arranged on town grounds.

In 1915 – with so many men away fighting in the First World War – the (men’s) Football Association (FA) suspended the men’s leagues and women’s matches surged in popularity in their absence. Supported by the FA as a means of fundraising for the war effort, women’s teams were allowed to use league grounds for matches and training and were often assisted by male players and coaches. Matches drew crowds of tens of thousands to stadiums across England.

Reports of women’s matches in the contemporary Football Special Magazine highlighted the initial reaction to women’s football in this era. Women’s teams had centre spread features alongside men’s, with no sign that it was unusual or extraordinary. A weekly column by ‘The Football Girl’ also discussed the game, providing insights into the earnest and organised efforts behind the sport.

As the war ended and men returned home, the popularity of the women’s game did not wane. At a record-breaking match on Boxing Day 1920 played at Goodison Park (home of Everton FC) the Dick, Kerr Ladies and St Helens Ladies (the top two women’s teams in England) played to 53,000 spectators, with over 10,000 turned away at the gates.

A large number of women’s teams had formed all over the UK and, reportedly, by 1921 every major town in England had a ladies’ team, with cities often having several. Naturally, this led to a movement to establish women’s football more formally. Demand had grown far beyond matches for charity and spectacle, with an appetite for leagues, a governing body and for women to play professionally.

The 1921 ban on women’s football

After the war, the continued success of women’s football became a threat to the men’s game. Equivalent league matches between men’s teams drew nowhere near as many crowds or headlines. Though the fundraising effort had been welcome during the war (Dick, Kerr Ladies alone raised the equivalent of millions of pounds), the popular view was that it was time for women to leave the pitches. There was even a suggestion that women’s teams were inappropriately allocating money raised from charities and paying players to appear. It was altogether one thing to have women playing football – but to pay them and essentially professionalise the sport was totally unacceptable to many.

So, in December 1921 the FA banned women from playing and using league pitches and facilities. The ban was justified by the claims of financial scandal, but it is telling that the committee could not resist also expressing their distaste at the women’s game, generally. Part of the resolution read:

Complaints having been made as to football being played by women, Council feel impelled to express their strong opinion that the game of football is quite unsuitable for females and should not be encouraged.[8]

This perceived unsuitability of football for women’s bodies persisted in contemporary press coverage. For example, a doctor interviewed in the Birmingham Daily Gazette considered kicking to be ‘too jerky a movement for women’, concluding that ‘… just as the frame of a woman is more rounded than a man’s, her movements should be more rounded and less angular’.[9]

The ban had a devastating effect. League football clubs barred female players from their pitches, and registered referees were banned from officiating at women’s matches. Unsurprisingly, the lack of adequate facilities made the sport unsustainable, effectively destroying the credibility the women’s game had built up. There were attempts to rally and continue as before, but the death blow had been struck.

Women continued to play over the coming decades, and it is a great shame that so little about these years is known or recorded. What could have been the establishment of one of the earliest and most successful women’s leagues in the world had been crushed.

The ban on English women’s football wasn’t lifted by the FA until 1971, by which time it had done severe damage to the sport which would take generations to unpick. England did not have a fully professional women’s football league until 2018.

脚注

- Jessica Macbeth, ‘Women's Football in Scotland: An Interpretive Analysis’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, Stirling University, 2004)

- Jean Williams, A Game for Rough Girls: A History of Women's Football in England (London: Routledge, 2003), p. 25.

- Nettie Honeyball, quoted in the Cornish Telegraph, 24 January 1895, p. 3.

- London Daily News, 5 March 1895, p. 5.

- This is a reference to the Progressive Women’s Club founded in London in 1892 by Emily Massingberd.

- Cardiff Times, 16 March 1895.

- Nettie Honeyball, quoted in the Cornish Telegraph, 24 January 1895, p. 3.

- FA Council minutes, 1921: from the FA Archive held at the National Football Museum, Manchester.

- Birmingham Daily Gazette, 7 December 1921.

Article text © Eleanor Dickens

撰稿人: Eleanor Dickens

Eleanor Dickens is a curator for Politics and Public Life in the Department of Contemporary Archives and Manuscripts at the British Library. She is critically engaged with research into women’s history and wider political protest and activism.