The Importance of Being Oscar Wilde: Rise and Fall of Wilde’s Literary Fortune in China

This article tells the story of Oscar Wilde in China since he was firstly introduce to Chinese audiences during the May 4th Movement. From the popular adaptations in the 1920s to the contemporary adaptation of The Importance of Being Earnest in Beijing, 2015, it charts the rise, fall and rise of Oscar Wilde and his literary legacy in China.

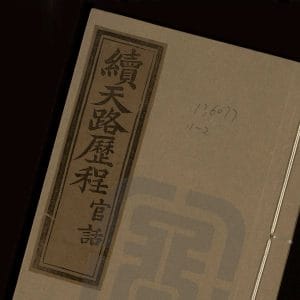

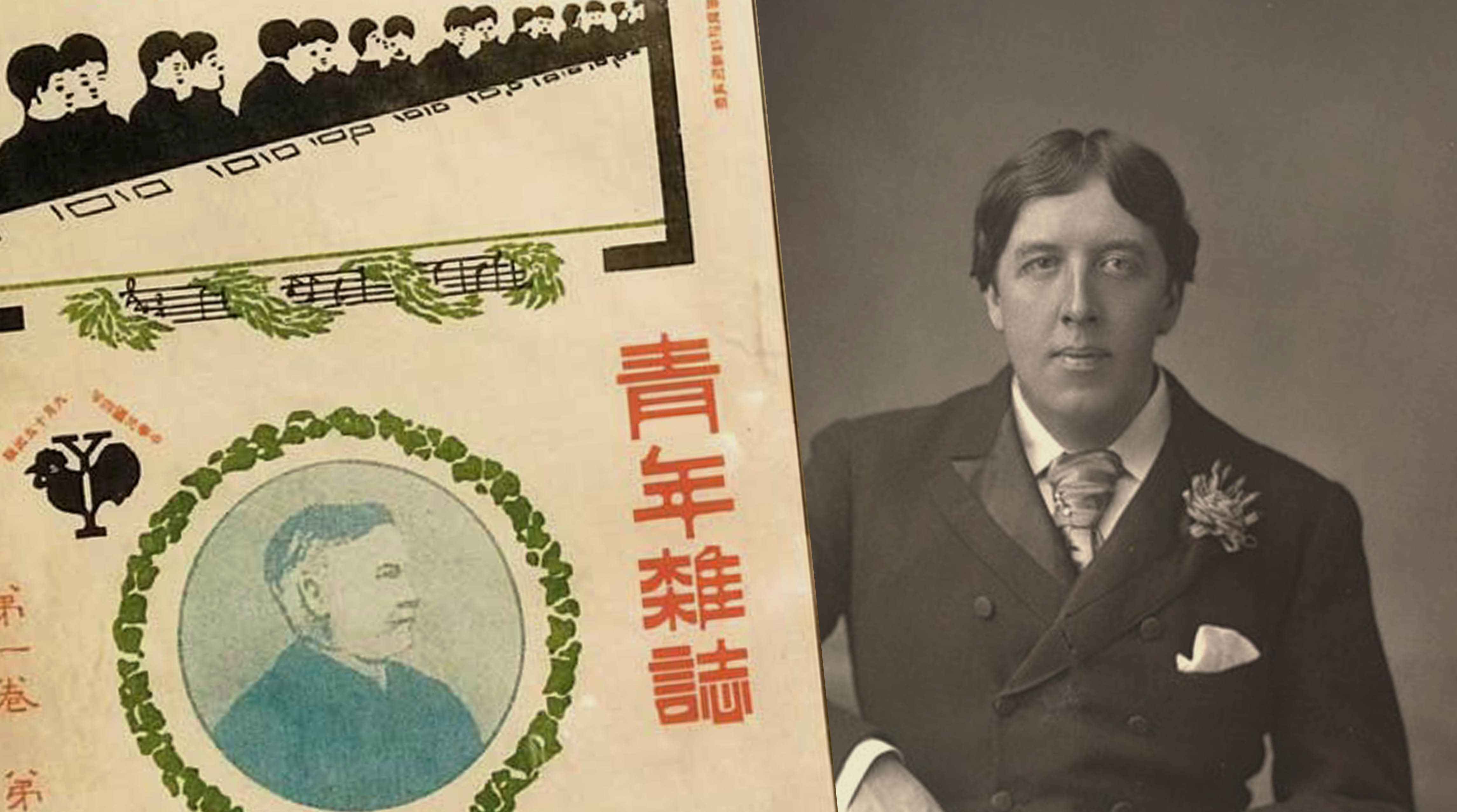

If we go by Oscar Wilde’s name in Chinese transliteration, Aosika Wang’erde (奥斯卡·王尔德), his literary fortune in China would have been all but guaranteed, with the Lucky Star smiling on him all the time. After all, Aosika (奥斯卡) shares the same glamour with the Oscars (the Academy Awards) whereas Wang’erde (王尔德) means ‘regal and virtuous’ or ‘virtuous King’. However, fate would not have it that way and Wilde’s literary fortune in China, since his first introduction by way of a 1909 translation of his short story ‘The Happy Prince’ rendered by Lu Xun (鲁迅) and his brother Zhou Zuoren (周作人), was destined to take a wild ride of rise and fall (and rise again).

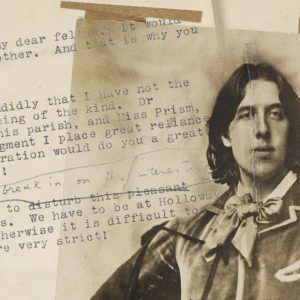

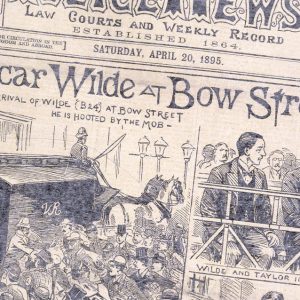

From adulation in the early decades of the 20th century to a long period of eclipse during the decades between 1940s and the end of the 1970s to resurgence ever since, Wilde’s literary fortune in China somehow parallels his dramatic career on his native soil, his rise with the glorious success of Salomé (1892–94), despite the initial ban by the Lord Chamberlain’s licensor of plays thanks to the sensitive nature of its biblical story, Lady Windermere’s Fan (1892), and The Importance of being Ernest (1895), his fall through the trials on account of his homosexual liaisons, his imprisonment (1895-97), exile (1897-1900) , and death of cerebral meningitis on 30 November 1900, and then a long path of reassessment of the man and his works through the lenses of queer criticism, political economics, postcolonial criticisms and rehabilitation, which culminates, so to speak, in a posthumous pardon in 2017 by Queen Elizabeth II because homosexual acts are no longer crimes in the United Kingdom.

Indeed, Wilde’s reception in China is as much about the man – a personality, an iconic as well as maligned cultural figure – as about his works, perhaps more so than any other Western authors in China.

The Lost Fan, Salomé’s Kiss, and the Early Adulation

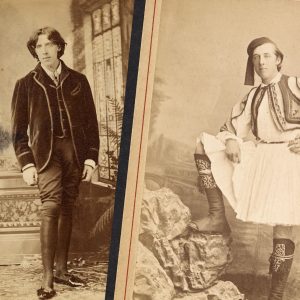

Like many Western authors, Oscar Wilde was introduced in China when the country was undergoing dramatic agitation during the May 4th Movement. Chen Duxiu (陈独秀), editor of the revolutionary New Youth Magazine saw in Wilde’s plays subversive social criticism whereas members of the Creation Society and New Moon Society found the Wildean ‘art for art’s sake’ aesthetics liberating. Wilde’s bold, outlandish public persona – his long hair, his in-your-face fashion statements, his quick wit and outspokenness, a mix of performance and expressions of personal philosophy perhaps – proved particularly refreshing for a young generation of college-educated Chinese who found the traditional Chinese cultural norms unbearably repressive. By the early 1920s, as a result of fervent interest, most of Wilde’s important plays had seen Chinese translations, including Salomé, Lady Windermere’s Fan, An Ideal Husband, and the Importance of being Ernest, some having several renditions.

The first Wilde play staged in China was Lady Windermere’s Fan, directed by Hong Shen (洪深) in 1924. It was less than two years after the failure of Zhao Yanwang (赵阎王 Yama Zhao), his adaptation of Eugene O’Neil’s Emperor Jones. Wilde’s Lady Windermere’s Fan seemed promising because it is not a talkfest like a typical Bernard Shaw play although there is so much more talk than a typical Chinese xiqu. It is not audaciously experimental like O’Neill’s Emperor Jones, whose use of expressionist storytelling fascinated theater-goers in London and New York but failed to engage the Chinese in Shanghai. And it is not overtly political either. Rather, it is a comedy of errors. A young wife who, suspecting her husband of infidelity, decides to leave him and her child when the ‘bad’ woman, who turns out to be her mother who abandoned her two decades earlier, comes to the rescue of the young damsel in distress. It’s a storyline that would appeal to the middle-class, bourgeois Shanghai theater-goers immensely. The ‘fan’ in the title of the play (lost by the young damsel at a compromising place and ‘recovered”’ by her mother in the nick of time) would grab their attention right away, reminding them of fans in such Chinese classics as Honglou meng (红楼梦, Dream of the Red Chamber) and the classic play Taohua shan (桃花扇, The Peach Blossom Fan). Indeed, a Chinese translation of the play published in 1919 goes by this title: Yishanji 遗扇记 (The story of lost fan). Despite its social satire, the play is light-hearted, suspenseful, and ends happily for all: suspicion cleared, love reconfirmed, and ‘bad’ woman redeemed through a selfless, sacrificial act of love. In addition, the play’s extravagant décor and fashion would appeal to the Shanghai bourgeois theater-goers in no small measure.

To ensure the success of this new adaptation undertaking, Hong Shen did a translation of the play himself, instead of using translations already available. Hong’s rendition was free-spirited, aiming for performability instead of literariness or ya (雅, elegance), the highest virtue of translation according to Yan Fu (严复, 1854-1921). In Hong’s rendition, the Wildean play assumes the Chinese title Shaonainai de shanzi (少奶奶的扇子, Young wife’s fan), which is much simpler and much more an attention-getter than Wendemier furen de shanzi (温德米尔夫人的扇子), a mouthful but far from being as suggestive. In addition to the lively, free-spirited rendition of the text, Hong recruited a cast of well-known talents for the production, he himself playing the important role of Lord Darlington as well as directing.

Although this successful adaptation – a five-day run with sold out audiences – did not have any sociopolitical impact anywhere near that of Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, it did offer some useful lessons for how to adapt Western classics for the Chinese stage, how to maintain a balancing act between ‘art for life’ – the mantra for the Chinese intelligentsia from time immemorial – and art-for-art, or rather, art-for-entertainment, and box-office concerns. Lady Windermere’s Fan was adapted into a film in 1939 and later Chinese xiqu genres such as Huju (沪剧, Shanghai opera) based on Hong Shen’s translation. It has remained in the Huju repertoire ever since.

Another Wildean play that saw an early Chinese production was Salomé based on a popular translation by Tian Han (田汉), who was exposed to Oscar Wilde’s work while studying in Japan (1916-22). In fact, he saw a Japanese adaptation of Salomé there, which had a successful run of 127 performances from 1912-25. As the story is told in the Bible, Salomé, stepdaughter of Herod II (the ancient Herodian kingdom of Judaea) demands the head of John the Baptist as reward for dancing the dance of the seven veils and kisses the head delivered to her on a silver platter before being put to death herself by Herod II.

Postcolonial critics today may find disturbing orientalism in the Wildean appropriation of the biblical story, in its portrayal of the exotic, oriental femme fatale. For Tian Han and his Creation Society kindred spirits, and indeed even for the Chinese today, regardless of its cultural origins, the Bible, holy book for the dominant religion of all European countries and the United States, is perceived in China to be quintessentially, archetypically Western. Therefore, a biblical story as retold by Oscar Wilde would be as occidental, or rather, Western, as can be. Chinese fascination with Salomé was inspired by the same desire then to learn from all things Western to save China and renew its culture. It is a warped version of orientalism, or Occidentalism, if you will, as the Chinese looked at the world from the eastern-most end – both geographically and culturally speaking – of the Eurasian landmass. Indeed, by the time of the 1929 adaptation, the Wildean play had already inspired many a Chinese Salomé, male and female, on and off stage, and many a variation of ‘Salomé’s kiss’ as motif or trope in literary and dramatic works as well as mannerism in real life.

The 1929 production directed by Tian Han based on his own Chinese translation garnered much attention. All the stars, tianshi (天时, right time), dili (地利, right place), and renhe (人和, right people), seemed perfectly aligned for this production: an ‘exotic’ Western story, a sexy Chinese title for Tian Han’s rendition, Shalemei (莎乐美, Sha pleasure beauty), and Yu Shan (俞珊, 1908-68), a young actress known for her beauty and daring attitude, cast in the title role. On the opening night on July 7, 1929 in Nanjing, the theatre was packed to the brim. When the show moved to Shanghai in August the same year, however, the usually receptive Shanghai didn’t seem too thrilled. It did not repeat the same success, partly because Yu Shan left the show due to pressure from her family. It was criticized by Liang Shiqiu (梁实秋), Harvard-educated professor of English and editor of the famous Crescent Moon Monthly, for its sentimentalism and rouyu zhuyi (肉欲主义, hedonism). A year later, Yu Shan would play the title role of Tian Han’s adaptation of George Bizet’s Carmen, another ‘notorious’ oriental, or rather, Western femme fatale.

An Incriminating Letter, a Picture that Kills, and the Importance of Being Oscar Wilde

The stellar early success Oscar Wilde enjoyed in China was followed by a long eclipse in China from the 1940s all the way to the end of the 1970s. The dimming of his star during those years was overdetermined by the dominant political ideology and cultural and literary discourse that would find the Wildean aestheticism not only useless, but also ‘decadent’ and corruptive. There was much denunciation of the whole Wilde canon although not a word was said about his homosexual encounters, the trials, etc. (homosexuality being a taboo in China for most of the 20th century) until the 1996 publication of a Chinese translation (奥斯卡·王尔德传) of Oscar Wilde, His Life and Confessions (1916) , a biography written by his friend Frank Harris.

The rehabilitation began soon after the Cultural Revolution was over. Today one would find Oscar Wilde just about anywhere, research articles, graduate theses, and books of all shapes, forms, and media, from his fairy tales to The Picture of Dorian Gray to his plays, in English, Chinese translation, and bilingual, full-text and simplified, put out by all kinds of publishing houses. His plays have been performed on numerous school campuses too.

The Picture of Dorian Gray, Wilde’s audacious 1890 novel that was roundly condemned for its perceived immorality, saw a new Chinese translation in 1983 (Yu Dafu translated the work in the 1920s, but somehow it was never published). Several more translations have been published since, including one rendered by Peng Enhua. One translation by Jiang Yunlin (姜允麟) published in 1988 is titled linghun de huimie (灵魂的毁灭, instead of the usual dao lian gelei de huaxiang, 道连·格雷的画像), which captures much of what the novel is about but loses the rich suggestiveness embodied in the original English title. The novel has since garnered its share of scholarly attention, too, with many journal articles analyzing it through different critical lenses, biographical, artistic, moral, psychological, and archetypal.

One reason for the renewed appeal of Oscar Wilde in China is his witty satire of Victorian society, which resonates with the way many people feel about China today – with its nouveau riche, consumerism, corruption, and so on. As a recent translator of Wilde’s plays, Bao Lengyan (鲍冷艳) sees it, many things presented in An Ideal Husband (理想丈夫) echo loud and clear in today’s China. For example, Sir Robert Chiltern, the not so ideal husband, has acquired his fortune and power through insider trading (as evidenced by the incriminating letter he had sent to Baron Arnheim). Many a Chinese Robert Chiltern has done the same and probably worse since China began economic reforms at the end of the 1970s. Some have fallen; others are still enjoying their ill-gotten gains. A big question the Chinese society has been wrestling with recently is whether to let these flawed people (many being bold pathfinders in the early days of reforms, ‘captains of industry’, to borrow from Carlyle) off the hook or to hold them accountable; and, as in Wilde’s play, whether such people deserve a second chance. An Ideal Husband meets the needs of a society where plays of satire are somehow scarce in its drama repertoire for complicated cultural reasons.

Despite the resurgence of interest in Oscar Wilde since the 1980s, his plays did not see a serious professional production in mainland China until 2015. The Importance of Being Ernest, or rather, Buke erxi (不可儿戏, not a child’s play), had a run from June 4 to June 16, catching considerable critical and media attention. The adapter of this play—in the capacity of both translator and director—is Zhou Liming (周黎明), a glamorous Wildean sort of character (minus the “scandalous” baggage perhaps) himself on the cultural scene in China today. Zhou chose Oscar Wilde for this 2015 endeavor because the parallels between London of the late Victorian era and the 2015 Beijing “are uncanny in terms of class consciousness, upward mobility and all the trappings of the gilded age.” A sizable (albeit still small in percentage of the Chinese population) “leisure class,” conspicuous in consumption and every facet of life-style, has emerged in China, especially in major metropolis such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou. China, for better or for worse, is finally ready for a “trivial comedy” for “serious” and perhaps not so serious people alike.

Zhou was fully aware of the creative license, the “latitude” he could (and perhaps would have to) take in adapting and directing this work for the Chinese stage, to give it “a uniquely Chinese twist.” He knew that a “faithful” rendition of the play, faithful to both the spirit and the letter, would be good for reading, but not necessarily good for the stage. All the culture-specific references in the original play, such as Tories, Anabaptists, Shropshire, would leave the typical Chinese theatre-goers scratching their heads. So Zhou reworked the story, from character names to locale to culture-specific references to make it resonate with prospective audiences for this production. The basic plot of Buke erxi still follows that of The Importance of Being Ernest although the setting is now Beijing, 2015. All of the main characters now have their easily recognizable Chinese reincarnations, e.g., John Worthing becoming Lu Huaxing (鲁华兴); Algy Moncrieff, Meng Yuanji (蒙元吉); Lady Bracknell, Pu furen (溥夫人), and so on.

Some loss in this “extreme” remake of the Wildean play is inevitable. For example, the rich meaning of the original title, The Importance of being Earnest—the play’s play with the term “earnest,” a linchpin for character and plot developments, loaded with comic irony mocking both the characters and the façade of “earnest” respectability of the Victorian era—is simply untranslatable. Buke erxi, a smart, attention-getting Chinese title, is no equivalent to the original because it is imposed from outside and has little to do with the characters caught in the comedy of manners very much of their own making. Nonetheless, by and large, Zhou’s Buke erxi is faithful to the spirit of The Importance of Being Earnest, a comedy of a bunch of nouveau riche leisure class characters conspicuously and indeed earnestly pursuing trivialities in the “gilded age” of the 21st century Beijing, a comedy that can be replicated in just about any major city across China today.

One can earnestly predict that so long as the “gilded age” still glitters, somehow, Oscar Wilde will remain a glamorous cultural figure, and more importantly, his works will remain relevant.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Shouhua Qi

Dr. Shouhua Qi is Distinguished Visiting Professor at the College of Liberal Arts, Yangzhou University and Professor of English at Western Connecticut State University. Among Qi’s most recent publications are The Bronte Sisters in Other Wor(l)ds (coeditor and contributing author, 2014) and Western Literature in China and the Translation of a Nation (2012), both published by Palgrave MacMillan. Qi is working on a book titled Adapting Western Classics for the Chinese Stage (to be published by Routledge in 2018).