The Industrial Revolution

In this article Matthew White explores the industrial revolution which changed the landscape and infrastructure of Britain forever.

The 18th century saw the emergence of the ‘Industrial Revolution’, the great age of steam, canals and factories that changed the face of the British economy forever.

Early industry

Early 18th century British industries were generally small scale and relatively unsophisticated. Most textile production, for example, was centred on small workshops or in the homes of spinners, weavers and dyers: a literal ‘cottage industry’ that involved thousands of individual manufacturers. Such small-scale production was also a feature of most other industries, with different regions specialising in different products: metal production in the Midlands, for example, and coal mining in the North-East.

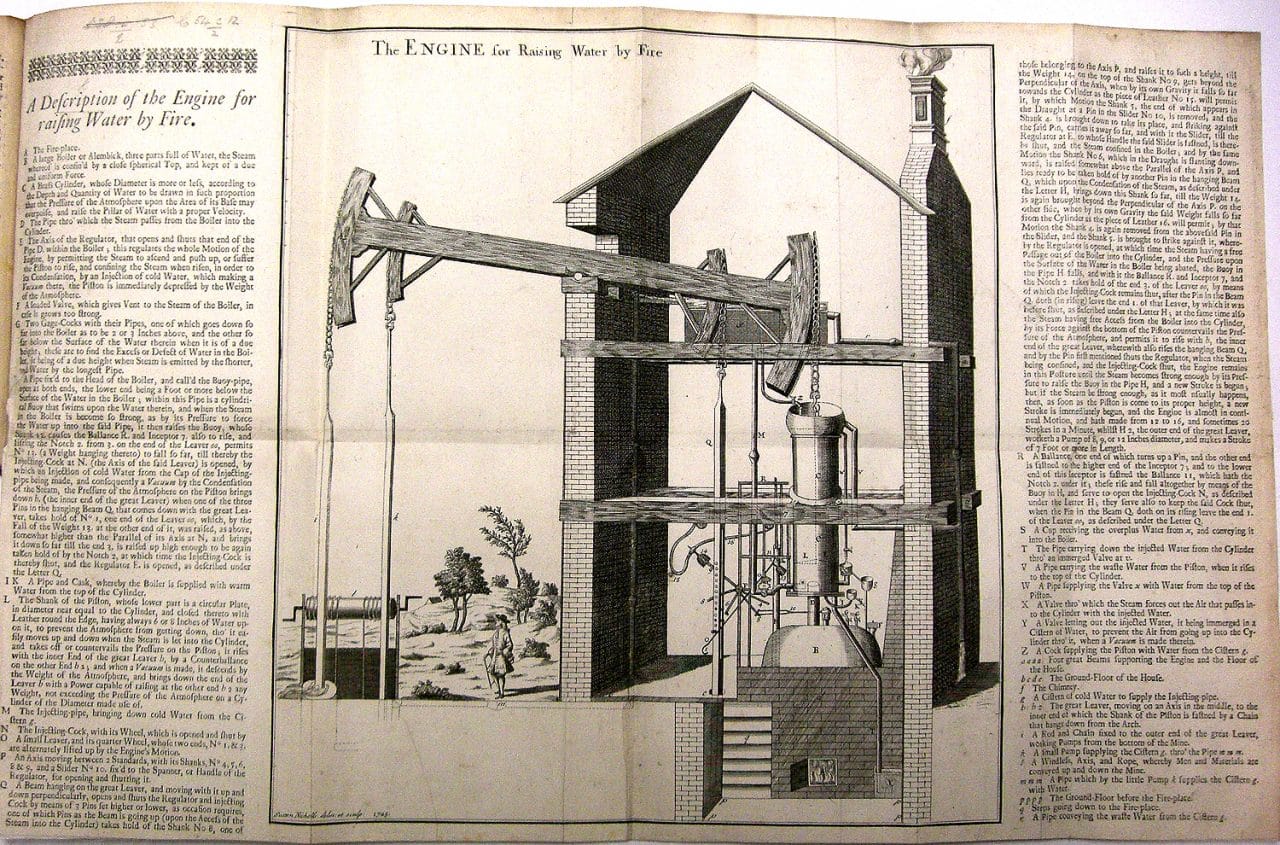

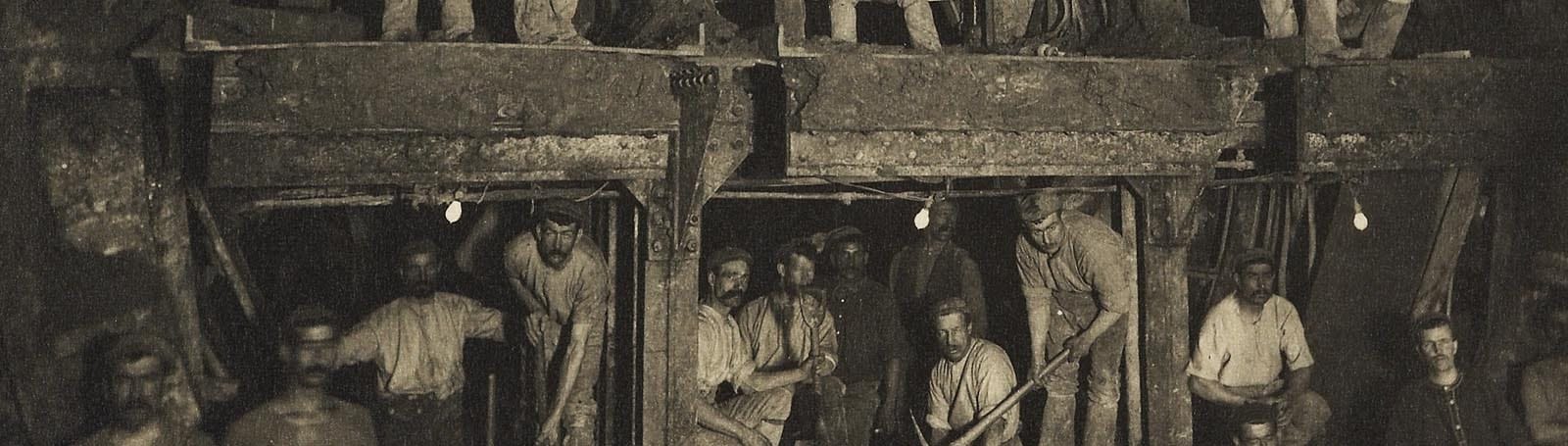

Steam and coal

Because there were limited sources of power, industrial development during the early 1700s was initially slow. Textile mills, heavy machinery and the pumping of coal mines all depended heavily on old technologies of power: waterwheels, windmills and horsepower were usually the only sources available.Changes in steam technology, however, began to change the situation dramatically. As early as 1712 Thomas Newcomen first unveiled his steam-driven piston engine, which allowed the more efficient pumping of deep mines. Steam engines improved rapidly as the century advanced, and were put to greater and greater use. More efficient and powerful engines were employed in coalmines, textile mills and dozens of other heavy industries. By 1800 perhaps 2,000 steam engines were eventually at work in Britain.

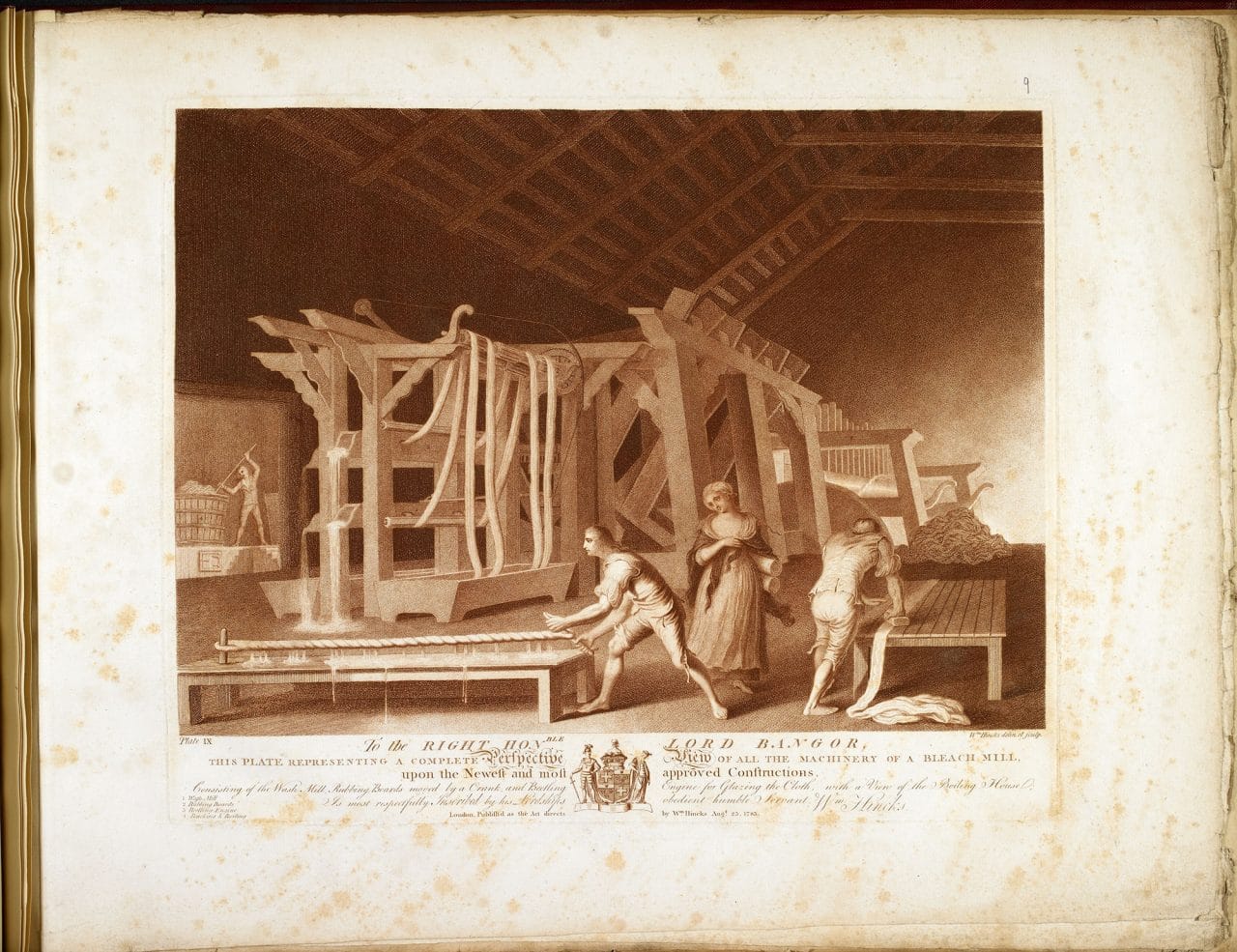

Factories

The spinning of cotton into threads for weaving into cloth had traditionally taken place in the homes of textile workers. In 1769, however, Richard Arkwright patented his ‘water frame’, that allowed large-scale spinning to take place on just a single machine. This was followed shortly afterwards by James Hargreaves’ ‘spinning jenny’, which further revolutionised the process of cotton spinning.

The weaving process was similarly improved by advances in technology. Edmund Cartwright’s power loom, developed in the 1780s, allowed for the mass production of the cheap and light cloth that was desirable both in Britain and around the Empire. Steam technology would produce yet more change. Constant power was now available to drive the dazzling array of industrial machinery in textiles and other industries, which were installed up and down the country.New ‘manufactories’ (an early word for ‘factory’) were the result of all these new technologies. Large industrial buildings usually employed one central source of power to drive a whole network of machines. Richard Arkwright’s cotton factories in Nottingham and Cromford, for example, employed nearly 600 people by the 1770s, including many small children, whose nimble hands made light-work of spinning. Other industries flourished under the factory system. In Birmingham, James Watt and Matthew Boulton established their huge foundry and metal works in Soho, where nearly 1,000 people were employed in the 1770s making buckles, boxes and buttons, as well as the parts for new steam engines.

Transport

The growing demand for coal after 1750 revealed serious problems with Britain’s transport system. Though many mines stood close to rivers or the sea, the shipping of coal was slowed down by unpredictable tides and weather. Because of the growing demand for this essential raw material, many mine owners and industrial speculators began financing new networks of canals, in order to link their mines more effectively with the growing centres of population and industry.The early canals were small but highly beneficial. In 1761, for example, the Duke of Bridgewater opened a canal between his colliery at Worsley and the rapidly growing town of Manchester. Within weeks of the canal’s opening the price of coal in Manchester halved. Other canal building schemes were quickly authorised by Acts of Parliament, in order to link up an expanding network of rivers and waterways. By 1815, over 2,000 miles of canals were in use in Britain, carrying thousands of tonnes of raw materials and manufactured goods by horse-drawn barge.

Most roads were in a terrible state early in this period. Many were poorly maintained and even major routes flooded during the winter. Journeys by stagecoach were long and uncomfortable. London in particular suffered badly when wagons and carts were bogged down in poor conditions and were left unable to deliver food to markets. Faced with these difficulties, local authorities applied for ‘Turnpike Acts’ that allowed for new roads to be constructed, paid for out of tolls placed on passing traffic. New techniques in road construction, developed by pioneering engineers such as John McAdam and Thomas Telford, led to the great ‘road boom’ of the 1780s.

The improvements achieved by 18th century road builders were breathtaking. By the 1830s the stagecoach journey from London to Edinburgh took just two days, compared to nearly two weeks only half a century before.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Matthew White

Dr Matthew White is Research Fellow in History at the University of Hertfordshire where he specialises in the social history of London during the 18th and 19th centuries. Matthew’s major research interests include the history of crime, punishment and policing, and the social impact of urbanisation. His most recently published work has looked at changing modes of public justice in the 18th and 19th centuries with particular reference to the part played by crowds at executions and other judicial punishments.