The Play’s The Thing

Penguin author Nancy Pellegrini discusses China’s challenges in translating Shakespeare for performance, and the Royal Shakespeare Company’s goal to create stage-friendly Shakespeare for Chinese theatre.

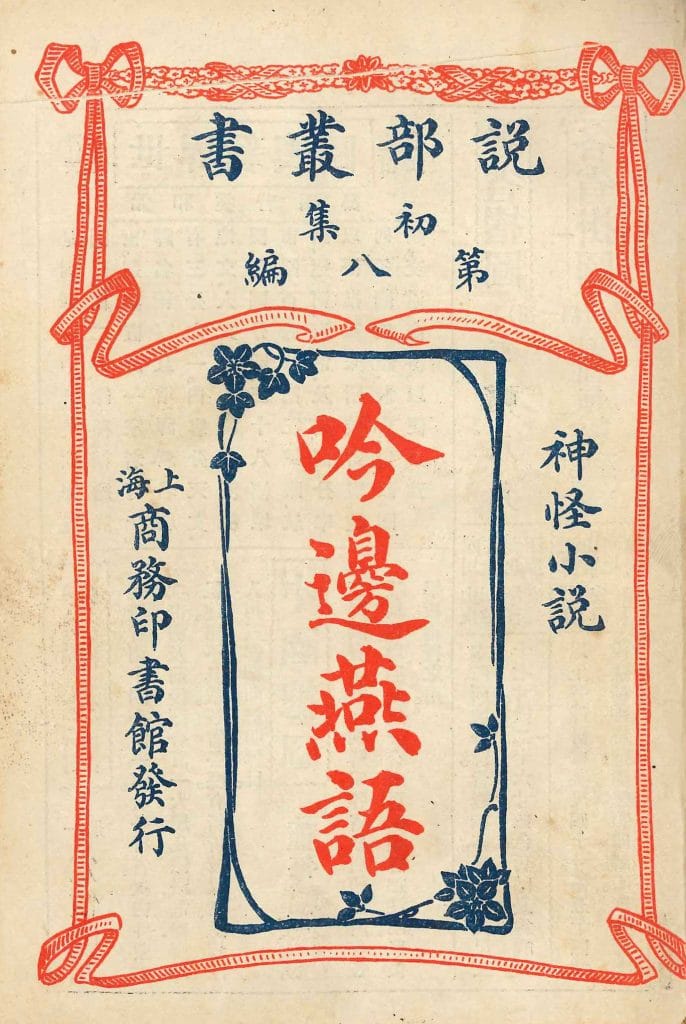

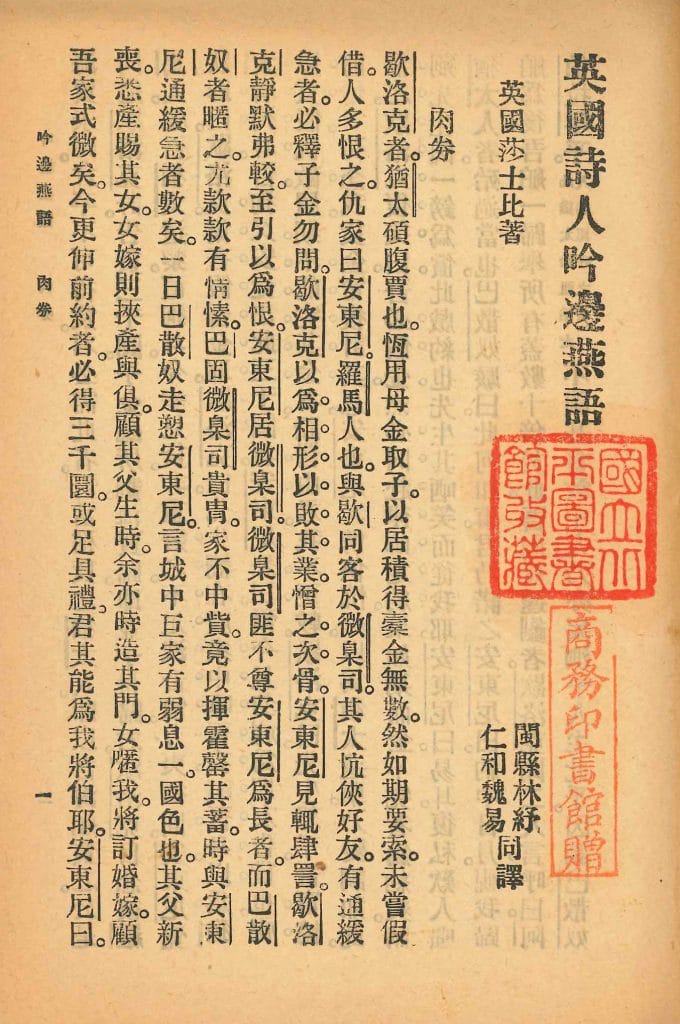

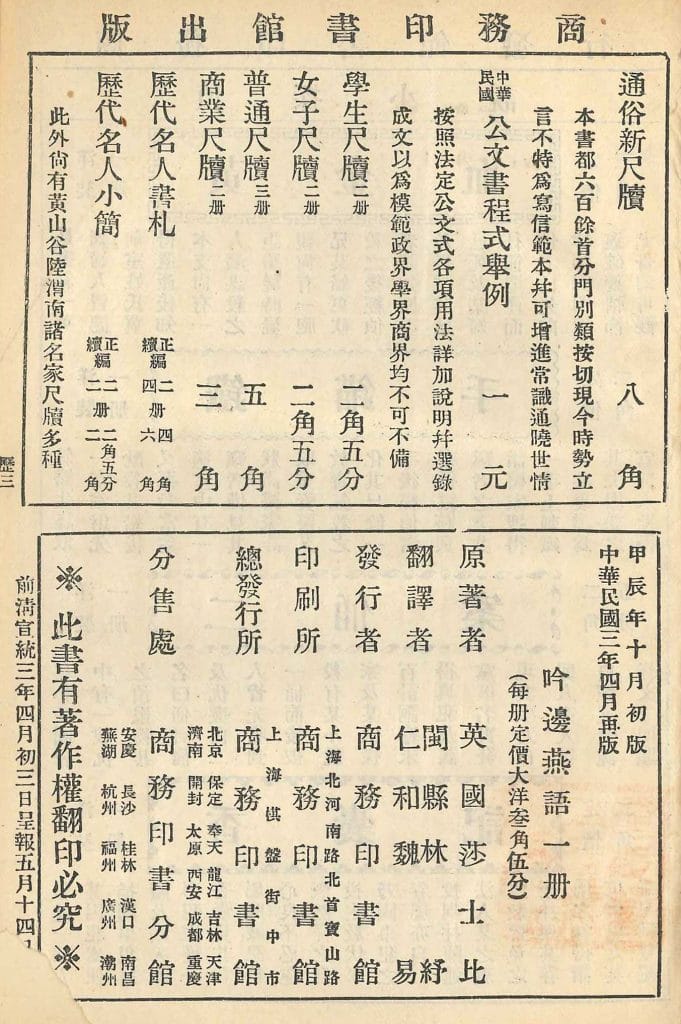

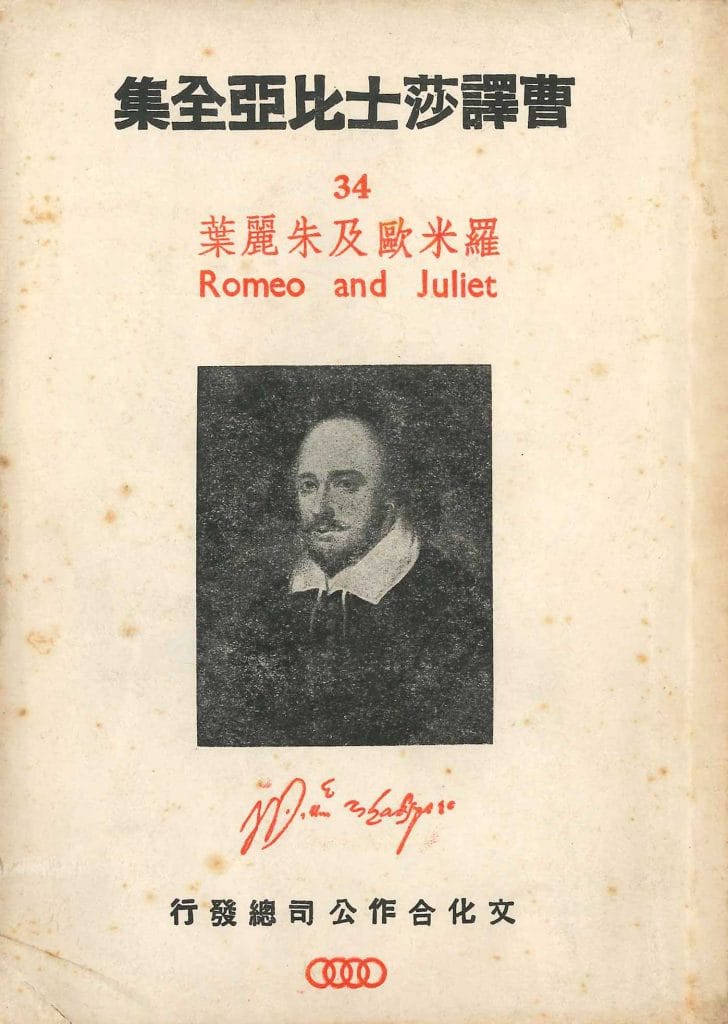

When William Shakespeare – or rather, his name – first arrived in China in the mid-19th century, it was not through colonialism or theatrical tradition. Rather, the Bard was a symbol of progressive thinking that many Chinese sought to emulate, believing that by adopting Western values they could better understand the Western enemy. Missionaries taught Shakespeare in their English-language schools, and traditional theatre (xi qu, or Chinese opera) troupes used translations of Charles and Mary Lamb’s Tales of Shakespeare, taking the plot outline and improvising the rest. Shakespeare’s full effect was limited to those who could speak English, and the full translations that emerged later were better suited to the page than the stage. This left actors and audiences struggling with unwieldy texts. In 2016, the 400th anniversary of the Bard’s death, the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) launched their Shakespeare Folio Translation Project, which embedded translators in rehearsal rooms alongside actors and directors bent on creating stage-focussed translations for China. This produced a truly collaborative effort, but one with a divided response – producing more plays versus disrespectfully undoing what had come before.

Shakespeare translation in any form presents myriad difficulties. But translating English into Chinese means marrying an ancient ideographic language to a modern one with a Latin alphabet. Translators had to sift through Shakespeare’s countless Bible and classical mythology references to determine which were crucial and which were expendable. And research materials were – and, to some extent, still are – comparatively scarce.

Variances in East and West symbolism could also cause confusion. Juliet tells Romeo to ‘swear not by the moon, th’ inconstant moon / that monthly changes in its circle orb / lest that they love prove likewise variable’, because to Shakespeare the sun was more reliable. But in China the moon is the symbol of innocence, purity and yes, love. Many translators also did – and do – eliminate sexual references, out of embarrassment or a misplaced loyalty to the Bard. When Cleopatra tells Antony, ‘I wish I had thy inches’, she means that she – at that moment – would rather be a man, and have the anatomy to prove it. But Chinese readers see, ‘I wish I were as tall as you’. Also problematic is iambic pentameter, that five-metre line of verse with short (unstressed) and long (stressed) syllables in each metre that Shakespeareans find crucial: ‘Two households, both alike in dignity / in fair Verona where we lay our scene’. Translators Sun Dayu and Bian Zhilin tried to recreate it using patterns of grouped characters and pauses, but with mixed results. And since Chinese has no verb ‘to be’, Hamlet ponders whether to live or to die.

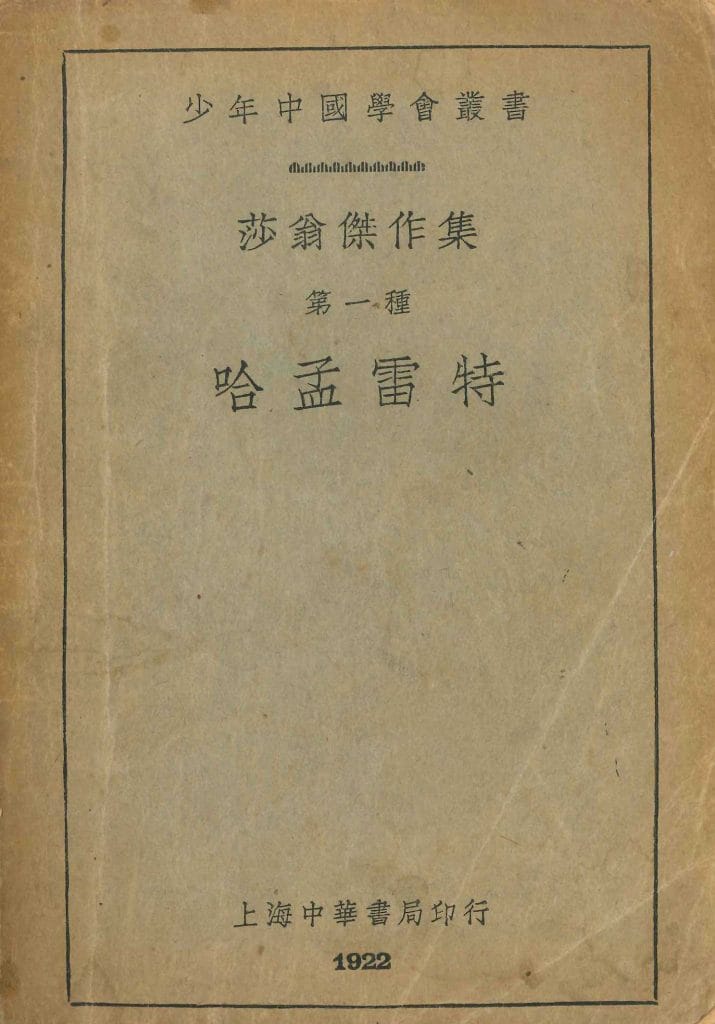

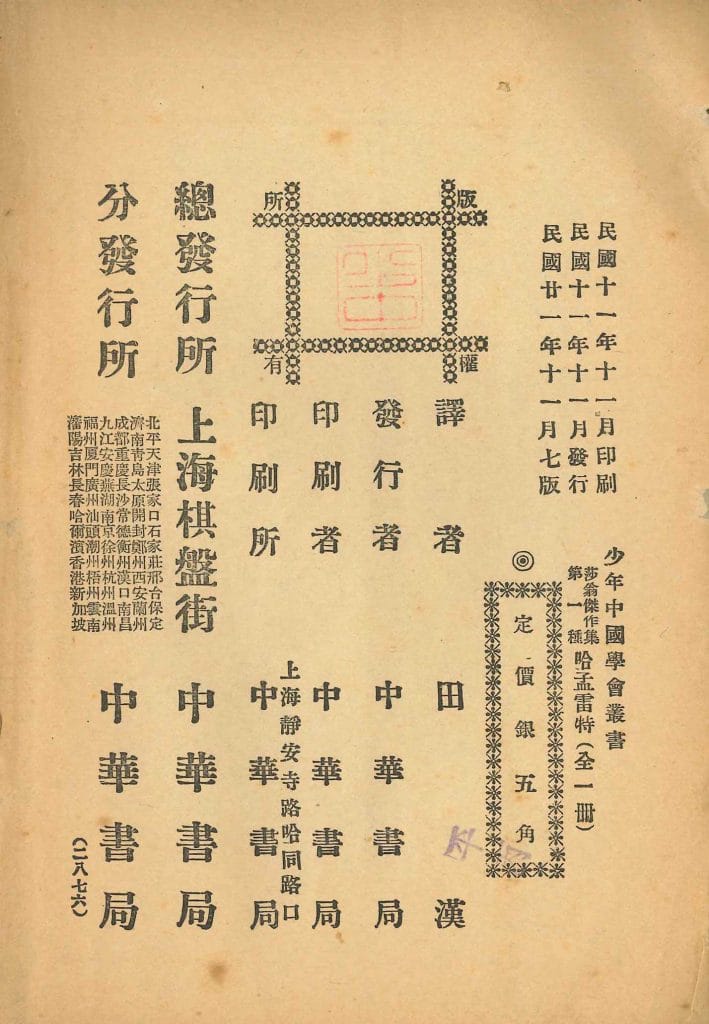

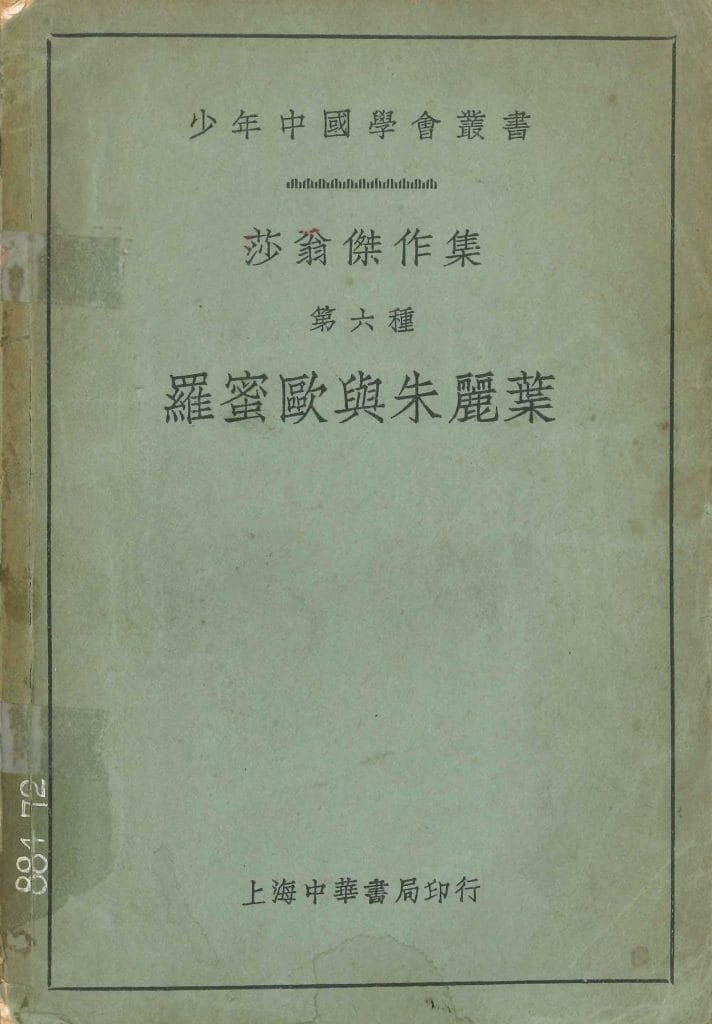

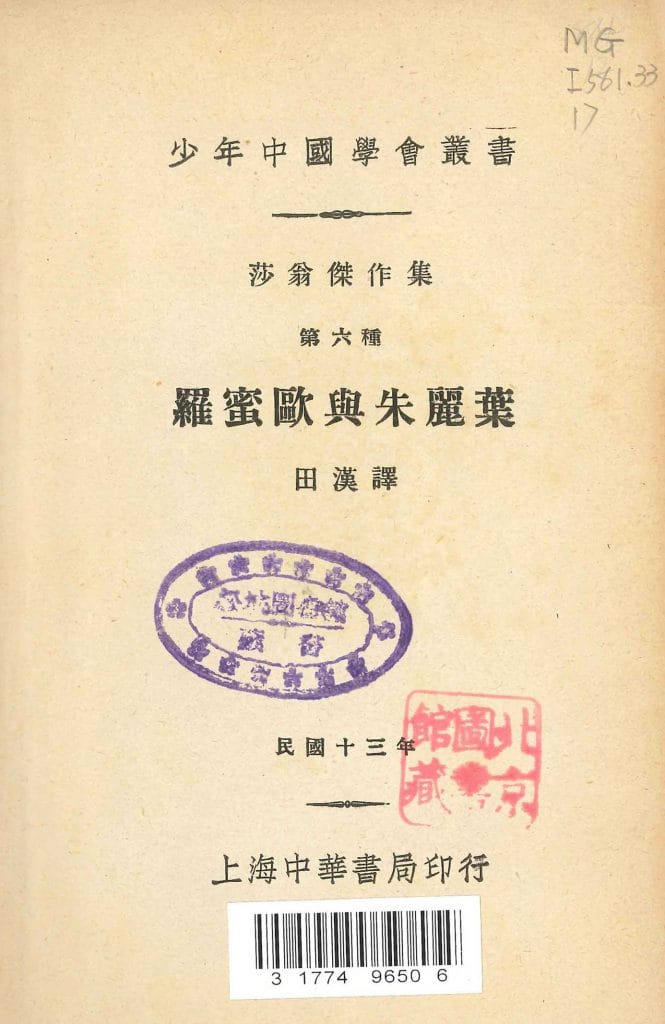

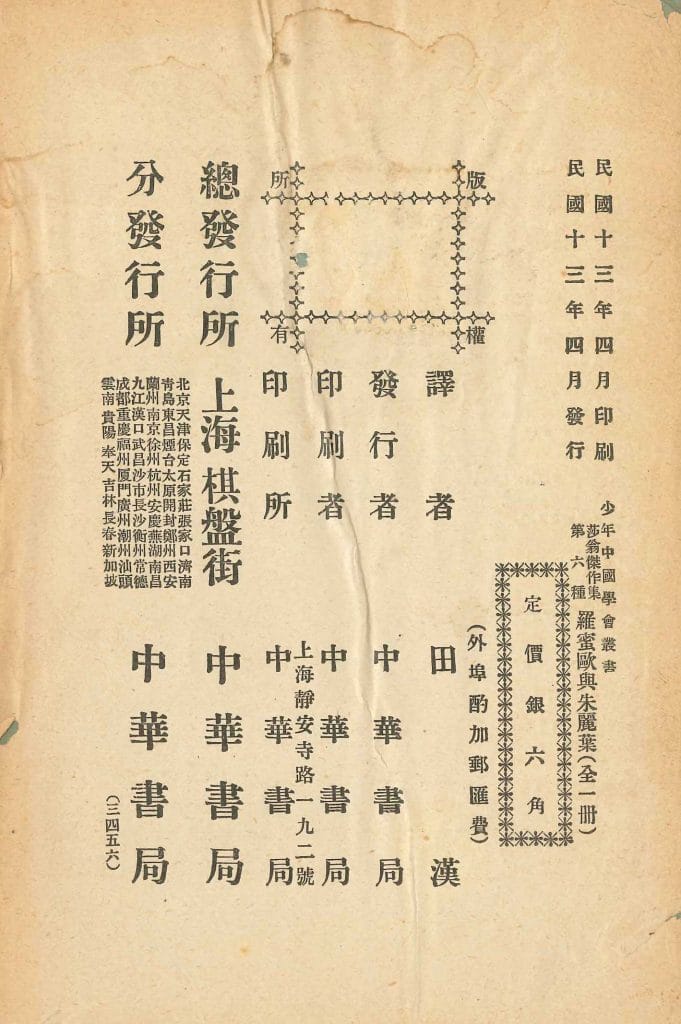

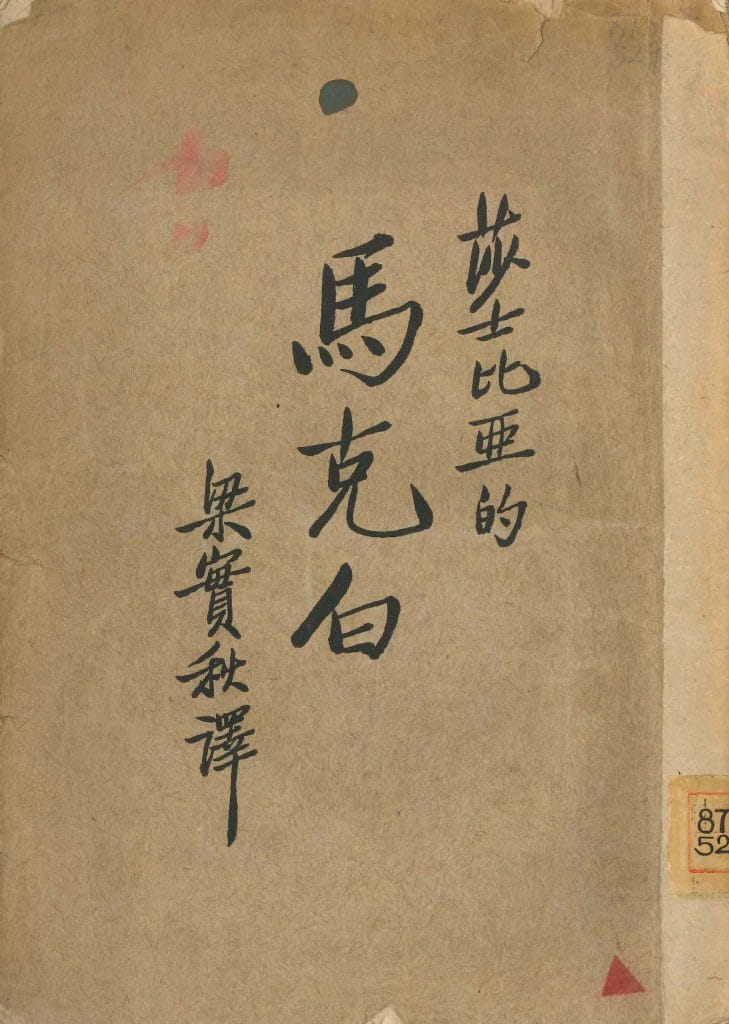

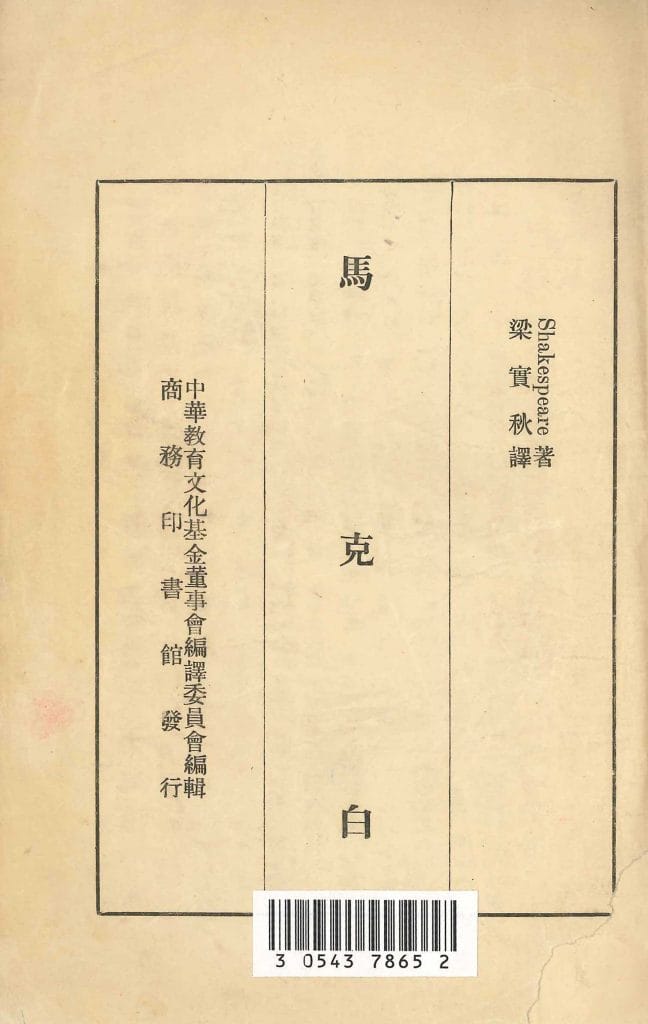

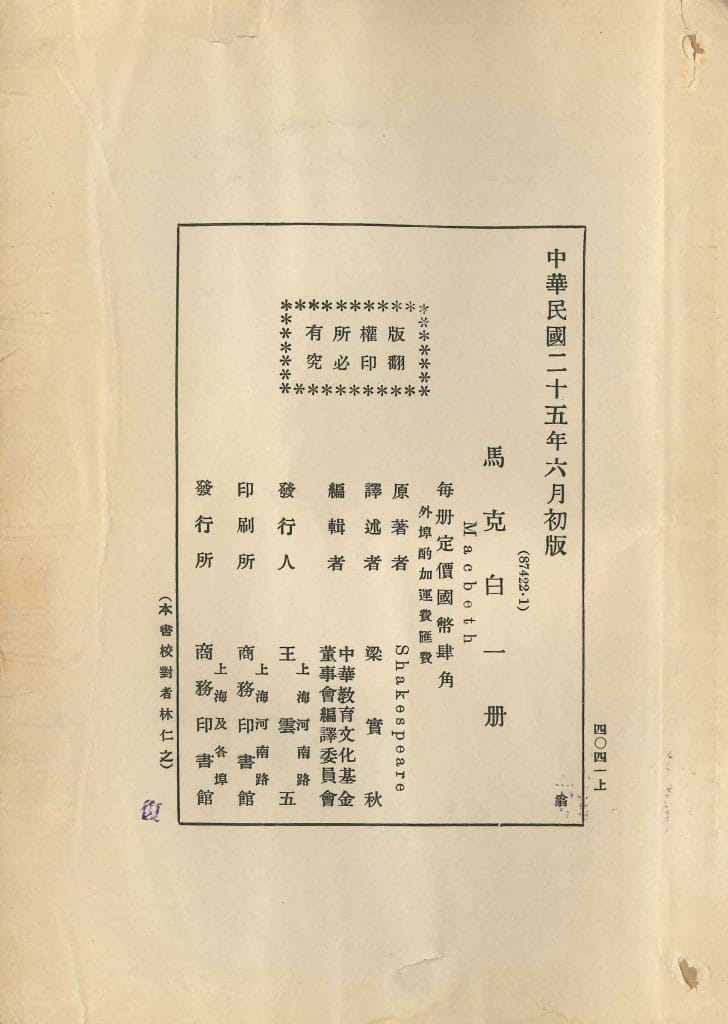

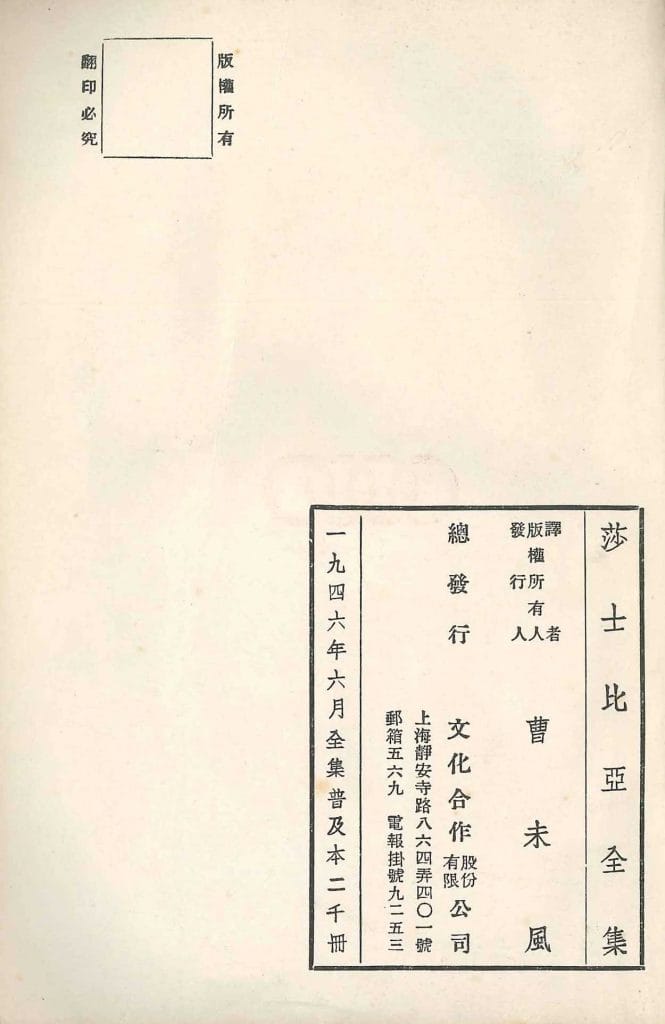

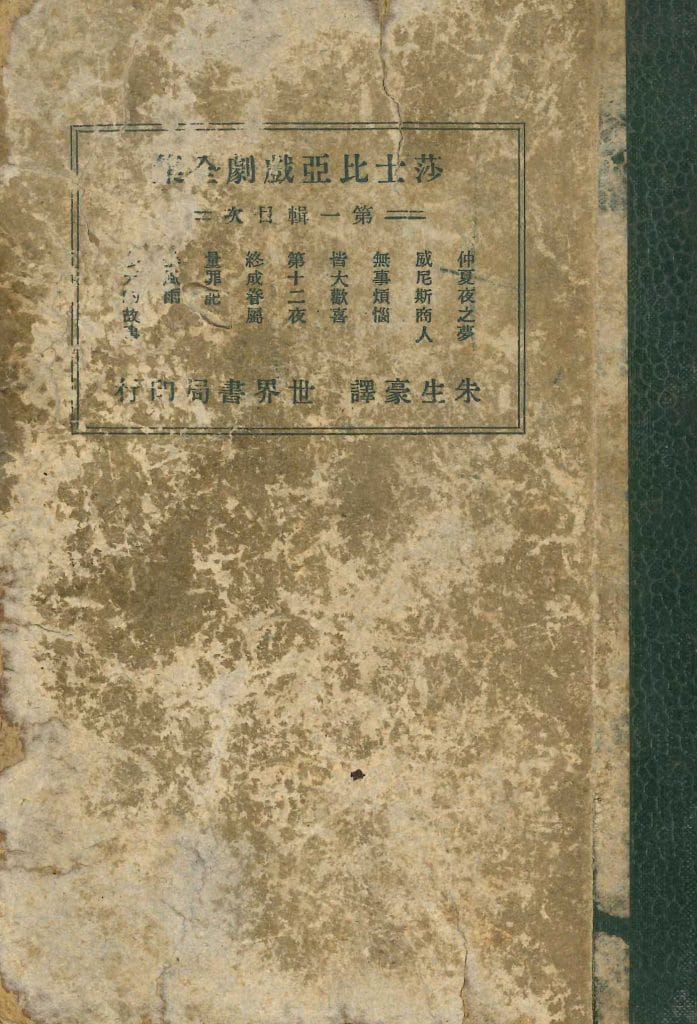

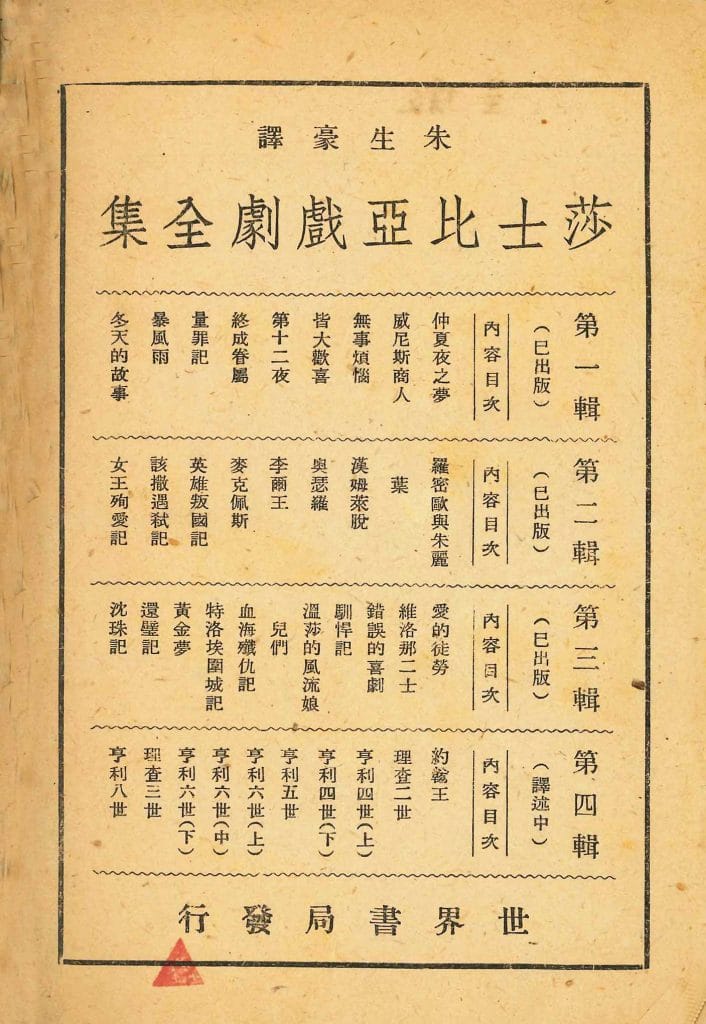

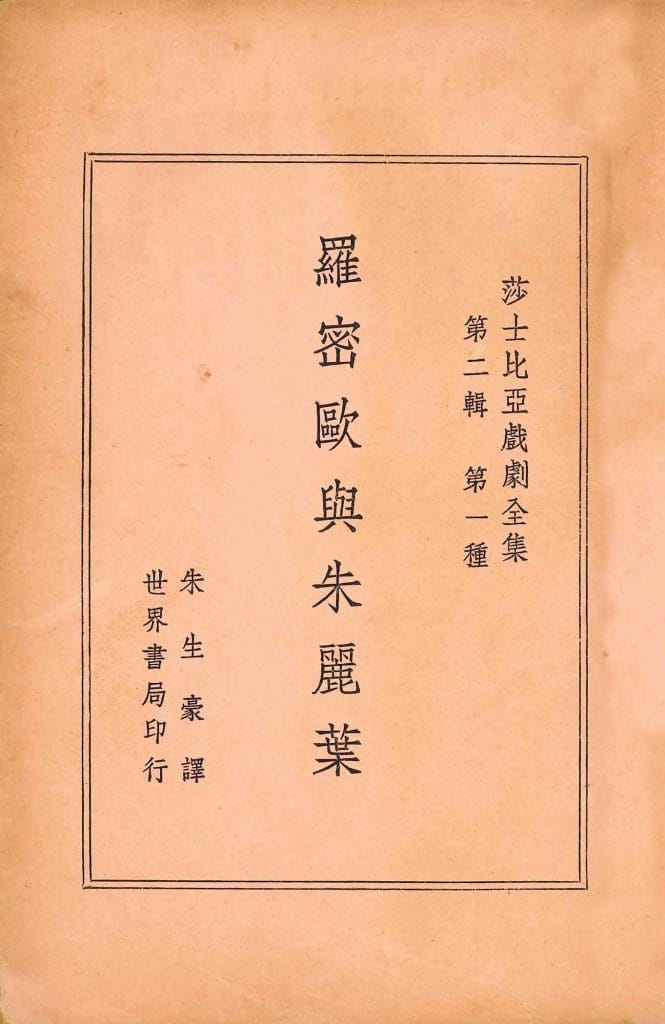

But despite such difficulties translators remained determined. While studying in Japan, future playwright and poet Tian Han heard the Japanese disparage Chinese culture because the nation didn’t even have a complete translation of Shakespeare; he responded by finishing Hamlet in 1921–22 and Romeo and Juliet in 1923–24, the country’s first fully translated plays, labelled today as beautiful but unplayable. Liang Shiqiu was the first Chinese speaker to translate all of Shakespeare’s works, beginning in 1930 and finishing 37 years later in 1967 in Taiwan; politics drove him to flee with the Nationalists, and his efforts weren’t seen on the mainland until the mid-1990s. Born in Beijing and educated at Harvard and Columbia, the meticulous Liang retained the slang and sexual terms that confused and even embarrassed his own family. To him, authenticity was key, and if this required a selection of reference books larger than any library of the period, so be it. War and foreign occupation was no excuse for shoddy translation. Liang is rarely used on stage, however; his scholarly approach works better in the classroom than on the boards.

For stage work, actors, directors and translators prefer Zhu Shenghao, China’s most poetic – and heroic – translator. Born to an upstanding but bankrupt family, Zhu was a voracious reader who was composing poetry at age 11. He attended Zhejiang University on a scholarship but always remained unrecognised by both the Nationalists and Communists, and therefore made translating Shakespeare his personal mission. Reduced to illness and dire poverty, he translated works sometimes two and three times because Japanese occupiers had destroyed earlier copies. He couldn’t afford a candle or oil for a lamp, so Zhu worked in sunlight by day, and by memory at night, checking his answers the next morning. In his final days, his teeth were infected, his tuberculosis had worsened and blood was oozing from his pores, but he refused medical attention, and only asked that his wife help him to the table. Zhu died in 1944 at age 32 with 31 plays completed and a further work in progress; according to his son, when Zhu died he was halfway through translating Henry V, the pen still in his hand.

This effort is in part what makes the RSC project so controversial. Frank Lee, a film-maker working on several Zhu Shenghao projects, feels that Zhu, acting independently, never got the respect he deserved from anyone in government. He also sees the RSC starting over with new translators as doing a grave disservice to both Zhu’s sacrifice and his respected (by Chinese Shakespeareans) and almost standardised work. ‘Translating Shakespeare is a horrendous job, but Zhu had all the basics’, he says. ‘The RSC could have collaborated with someone to make Zhu’s works more suitable for stage. Starting over is crazy’.

Raymond Zhou, theatre maker and noted film critic also agrees that a new body of work was unnecessary, and possibly short-sighted. ‘People today do not have the mastery of Chinese that the old generation did’, he says, explaining that he has just finished his own translation of Hamlet that built on the work of Zhu and Bian Zhilin. ‘My version focuses on the puns, which Zhu ignored, and changed his 1940s style of dialogue into the current one’, he says. ‘But there should be room for more than one style, because the stage treatment may require different approaches’.

Nick Rongjun Yu, playwright and vice president of the Shanghai Performing Arts Group, of which the Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre (SDAC) is a part, helped shepherd the RSC programme by holding its first performance – although he initially baulked at presenting Henry V. ‘England fighting with France is not that interesting’, he says. ‘But in this play , the audience can see how a leader becomes a leader; how a small man becomes a king’.

Like Zhou, Yu also favours a hybrid approach , even when using new material. ‘I’m a playwright; I wanted the dialogue and words to be perfect’, he says. ‘If Liang Shiqui had a line that worked better, I would use that’. Yu said the rehearsal room gave him new appreciation for the ivory tower translator. ‘Usually we use Zhu Shenghao, but I found Liang’s version more correct. Zhu and Fang Ping (who did translation in verse) cut slang, and some sexual terms; Liang’s version is long and boring, but really correct’.

The result was a model that pleased many, particularly audiences – shows were sold out throughout the run. ‘The translation worked beautifully with both the actors and the audience’, says Shihui Weng, project manager on the RSC initiative. ‘Many said it was the first time they really understood and fell in love with Shakespeare’s history plays’. She detailed the time RSC associate director Owen Horsley and translator So Kwok Wan spent with the actors discussing language nuances and character revelations. ‘Lan Haimeng (Henry) was extraordinary, especially at those long soliloquies’, she says. ‘You really see him living the journey of learning how to be a leader. But making theatre is a constant process’, she continues. ‘There’s always space to explore’.

‘Any company doing Henry V can use this script; I think it’s wonderful’, Yu says. ‘This is a good model’. And while not all theatre companies have the funding, playwriting experience, or English ability of Yu and the SDAC, it’s an important start to encouraging more productions and enhancing the audience experience. Joseph Graves, Shakespeare professor and co-founder of the PKU World Institute of Theatre and Film, points out that other than Tian Han and Cao Yu, Chinese translators have been scholars rather than playwrights. ‘Although many translations are to be resoundingly applauded, they were not written [for] the Chinese actor’, he says. He adds that Shakespeare presents completely realistic characters, revealing both what they say and what they think; translators who do not understand Shakespeare’s focus on performance serve neither actors nor audiences. ‘The RSC understands this, perhaps better than any company in the world, and this is their motivation behind translating work in China’, he says. ‘It is an invaluable, and simultaneously, a momentous task’. And it could change Shakespeare in China forever.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Nancy Pellegrini

Originally from Long Island, New York, Nancy Pellegrini has worked in Europe and Asia for over two decades and has been covering China’s performing arts and classical music scene since 2005. She is the stage editor and writer for Time Out Beijing and Time Out Shanghai magazines and the author of the Penguin Special The People’s Bard: How China Made Shakespeare Its Own (Penguin Random House 2016) She has written on China’s art and culture for Christian Science Monitor, South China Morning Post, Berkshire Dictionary of Chinese Biography, Tatler, The Strad, Gramophone, International Piano, and Modern Painters, among others. She lives in Beijing, China.