The race to record sound

Over 140 years ago, inventors across the globe busied themselves with trying to create a machine to capture soundwaves. Harriet Roden delves into the stories of the key players in the race to record sound.

Histories of sound recording often begin with Thomas Edison’s invention of the phonograph in 1877. This hand-cranked machine was the first to take soundwaves and play them back.

Edison was not the only person who set out to record sound.

The 19th century was a hive of activity, across the world inventors had set about creating machines to tackle some of life’s inconveniences. Beyond the steam locomotive and electric lightbulb, ventures were sought to improve the art of communication – the telegraph, typewriter and telephone all provided new means to share ideas and thoughts across wider distances.

The phonautograph

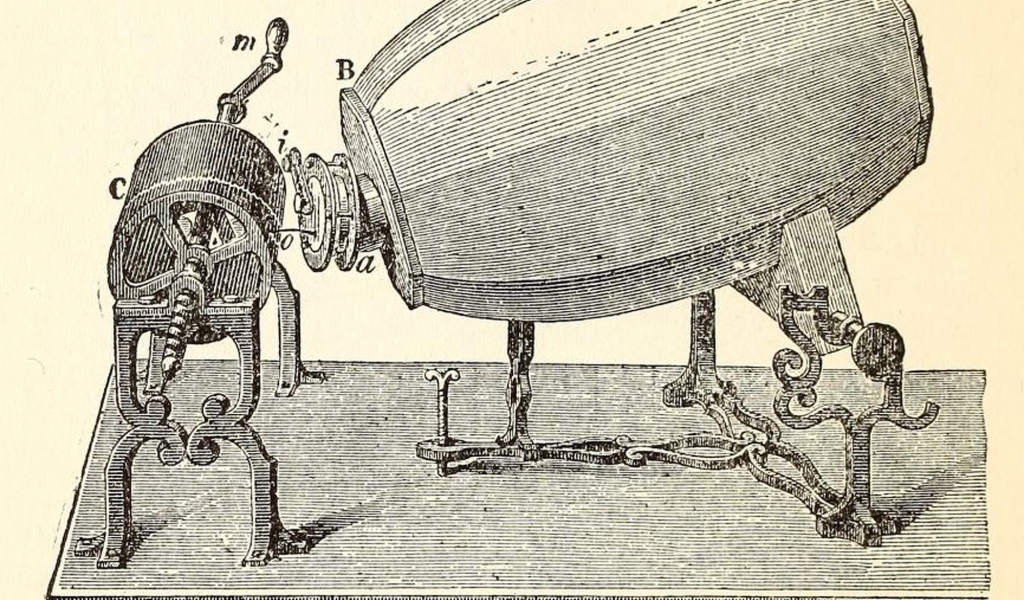

In the years preceding Edison’s success many had occupied themselves with the study of phonography, the scientific description of sound. When Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville (1817–1879) patented the phonautograph in 1857, his invention aimed to aid the understanding of the composition of human-made sound.

This machine transferred changing air pressure via a diaphragm, which in turn caused a stylus to move along paper coated in a thin layer of black soot. The result was a depiction of a sound wave.

Illustration of Eduard-Leon Scott de Martinville’s Phonautograph

The work of Charles Cros

Inspired by Scott de Martinville, the French author and scientist, Charles Cros (1842–1888) used the initial design of the phonautograph to consider how to lift the sounds from the paper and listen to them again.

Cros worked to draw out the paleophonic process; this involved taking the soot-covered paper from the phonautograph and replacing it with a glass disc. From there, he suggested that the glass could be photoengraved to create grooves that, when followed by a stylus, could be replayed.

In April 1877 Cros sent a paper outlining this process to the French Académie des Sciences in Paris.

Just three months after Cros had submitted his paper, the recognisable first line of ‘Mary Had A Little Lamb’ – recorded just minutes before – began to play out in a lab in New Jersey, New York. Edison’s phonograph worked. It was successful in recording sounds and replaying them.

Cros, on the other hand, never made a working model of the paléophone.

The Phonograph

The phonograph worked in a similar way to the phonautograph: it transferred changing air pressure via a diagram to a moving stylus. However this time the stylus pressed into a cylinder wrapped in tin foil.

When the motion was reversed, the stylus would track along the grooves in the cylinder – and whether the machine was attached to a horn or ‘ear tubes’ – the listener would be able to hear the faint recording.

Tinfoil phonograph, replica from 1877

When debuting this model, Edison wrote about how he envisioned the phonograph would be used in society. He predicted we would use the phonograph for ‘Letter-writing, and other forms of dictation books, education, reader, music, family record; and such electrotype applications as books, musical-boxes, toys, clocks, advertising and signalling apparatus, speeches, etc.’.[1]

This predictions are startling true. Today we have audiobooks and record players, as well as toys that talk and virtual assistants that tell the time. But first, technological improvements had to be made.

Beyond the tin foil cylinder

Sheets of tin foil are not the most durable; they rip, tear and warp. Edison recognised this, as did other inventors like Chichester Bell and Charles Tainter. To be able to market the phonograph, the recordings needed to be replayed more than once.

Over ten years after that moment in the New Jersey lab, Edison debuted an improved model. He said he was ‘prevented from perfecting it sooner by reason of pressure of other business’, most likely focusing his attention on his lightbulb and the distribution of electric power.[2]

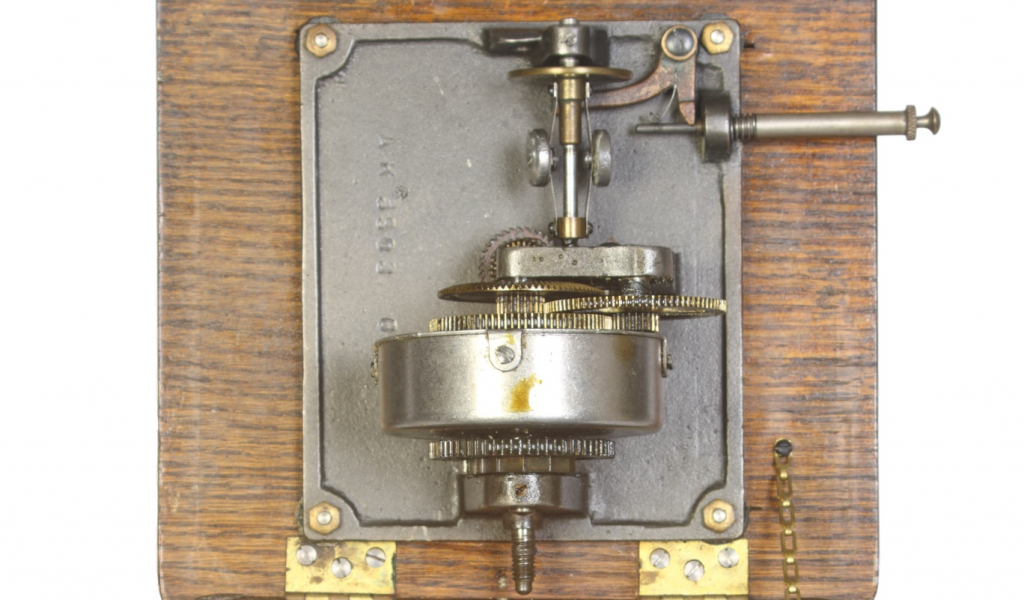

This perfected phonograph’s major new features were the wax cylinder and an electric motor. The wax proved to be stronger than the tin foil, and reports stated that it overcame ‘the metallic, nasal’ tone of the tin foil. As the cylinder was now turned steadily by electric motor, rather than by hand, the recording could be played back at the same speed at which it was recorded.[3]

Edison phonograph, 1893

Edison’s Class M phonograph was produced from 1889, and is closely related to the Perfected Phonograph. The machine was conceived at a time when the main use for the phonograph was considered to be office dictation and transcription. In this view the speaking tube is fitted.

A cylinder coated in wax, rather than with tin foil, was the innovation of Chichester Alexander Bell and Charles Tainter, who introduced the graphophone in 1887.

Columbia disc graphophone, 1903

Recorded sound in everyday life

Now with two inventions that worked for everyday use, companies like the American Graphophone Company and the Edison Phonograph Company were founded to manufacture and sell recorded sound to the public.

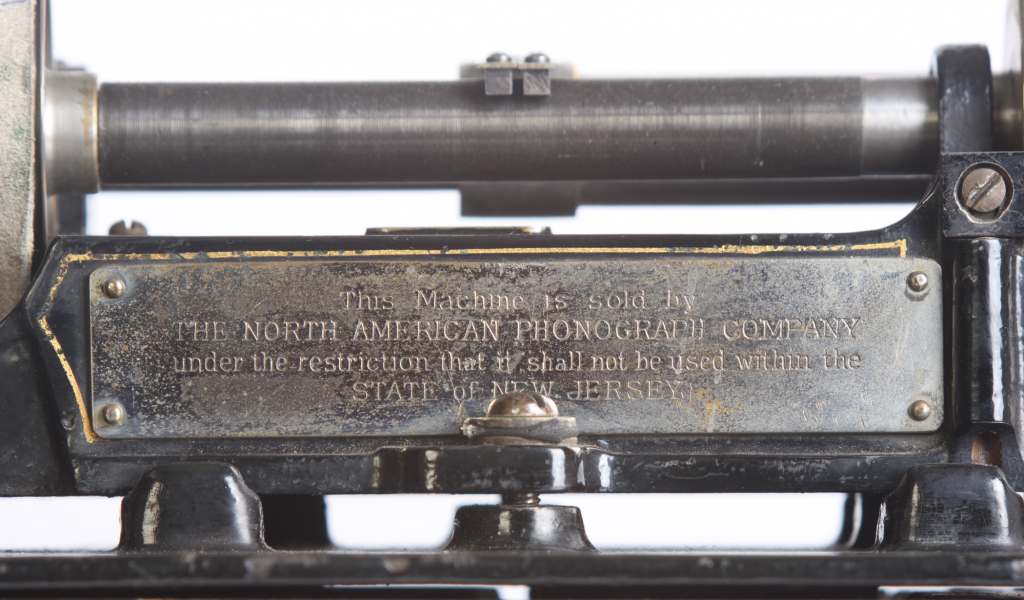

Initially some companies established a rental system, such as the North American Phonograph Company of New York who began to rent out phonographs for $40 a year for use as dictation machines.

Edison phonograph, 1893

This machine is sold by The North American Phonograph Company under the restriction that it shall not be used within the state of New Jersey.’

However, others quickly began to use recorded sound to sell records to raise funds for charity, to record wildlife, as well as record music and with that we have the recognisable tomes of the beginnings of how we use recorded sound today.

脚注

- Thomas A Edison, ‘The Phonograph and its Future’, North American Review, 126:262 (May 1878), p. 531.

- Exhibit of Edison Phonograph. Source: Scientific American, 58 (26 May 1888), p. 328. Published by: Scientific American, a division of Nature America, Inc.

- The Edison Phonograph in England. Source: Scientific American, Vol. 59, (4 August 1888), pp. 72–73

Banner image © Laura White

撰稿人: Harriet Roden

Harriet Roden is a content producer specialising in bringing archival collections to life for a range of audiences. Since 2019, Harriet has worked alongside colleagues to deliver the digital engagement strategy for the Unlocking Our Sound Heritage project, which aims to preserve and provide access to thousands of the UK’s rare and unique sound recordings.