The rise of cities in the 18th century

Cities expanded rapidly in 18th century Britain, with people flocking to them for work. Matthew White explores the impact on street life and living conditions in London and the expanding industrial cities of the North.

Life in the 18th-century city would have provoked a dazzling mixture of sensations: terror and exhilaration, menace and bliss, awe and pity.

Population Growth

The population of Britain grew rapidly during this period, from around 5 million people in 1700 to nearly 9 million by 1801. Many people left the countryside in order to seek out new job opportunities in nearby towns and cities. Others arrived from further afield: from rural areas in Ireland, Scotland and Wales, for example, and from across large areas of continental Europe.

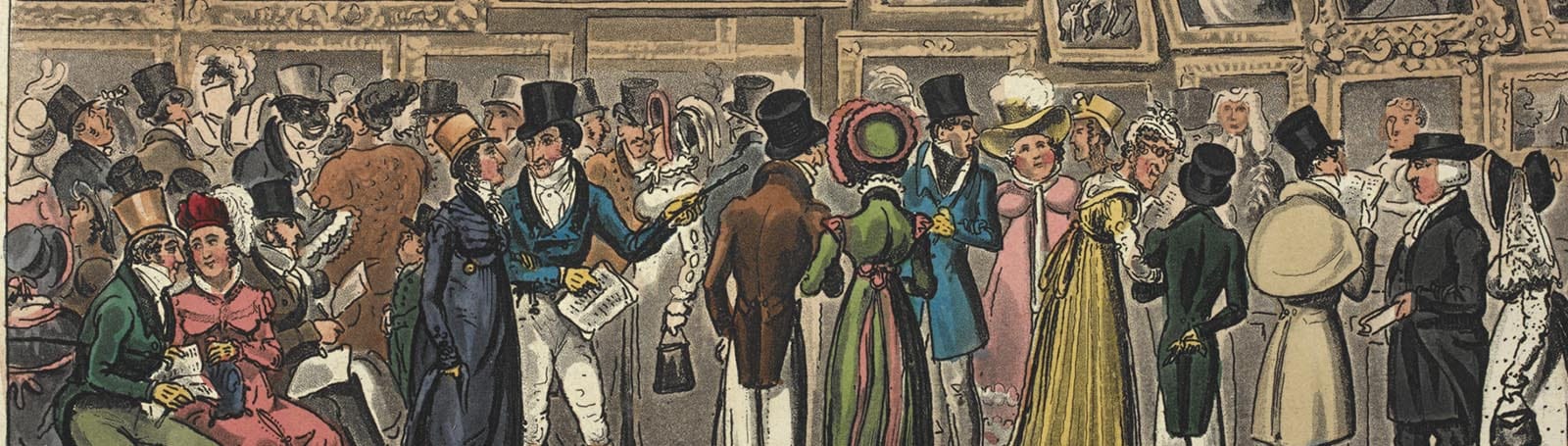

By today’s standards, most 18th-century towns possessed remarkably young populations. Young people were drawn to urban areas by the offer of regular and full-time employment, and by the entertainments that were on offer there: the theatres, inns and pleasure gardens, for example, and the shops displaying the latest fashions.

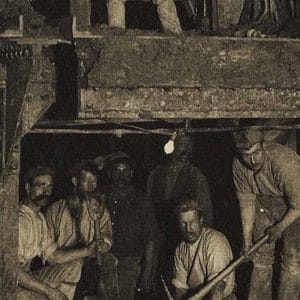

London in particular was flooded with thousands of young people every year, many of whom worked as apprentices to the capital’s thousands of tradesmen. Other new arrivals gained employment as domestic servants to the dozens of aristocratic families that began spending much of their time in elegantly built townhouses.Though death rates remained relatively high, by the end of the 18th century London’s population had reached nearly 1 million people, fed by a ceaseless flow of newcomers. By 1800 almost one in 10 of the entire British population lived in the capital city. Elsewhere, thousands of people moved to the rapidly growing industrial cities of northern England, such as Manchester and Leeds, in order to work in the new factories and textile mills that sprang up there from the 1750s onwards.

Street Life

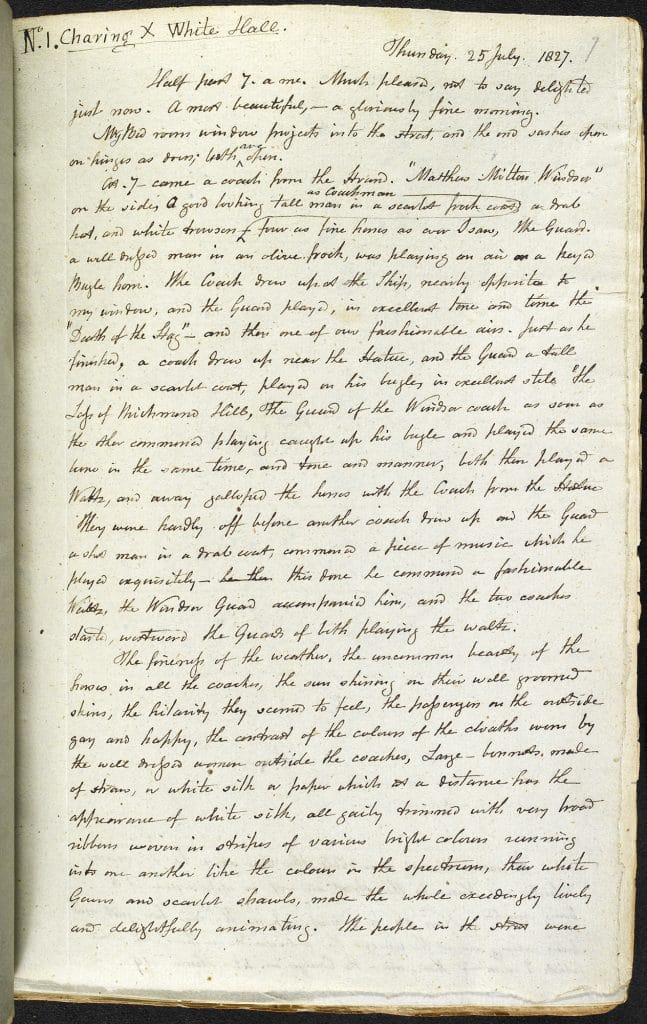

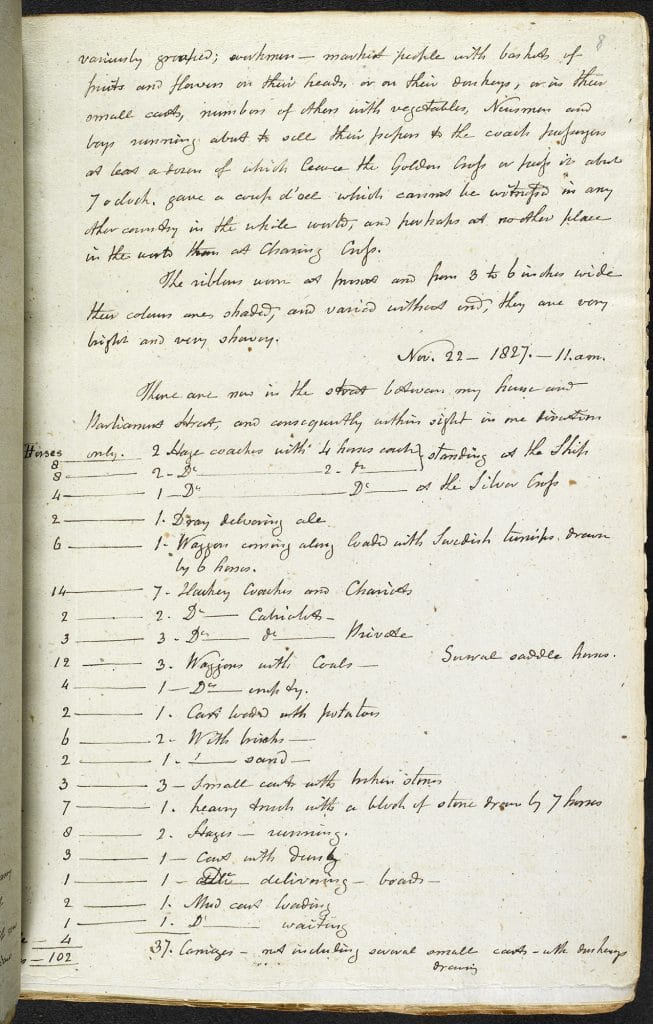

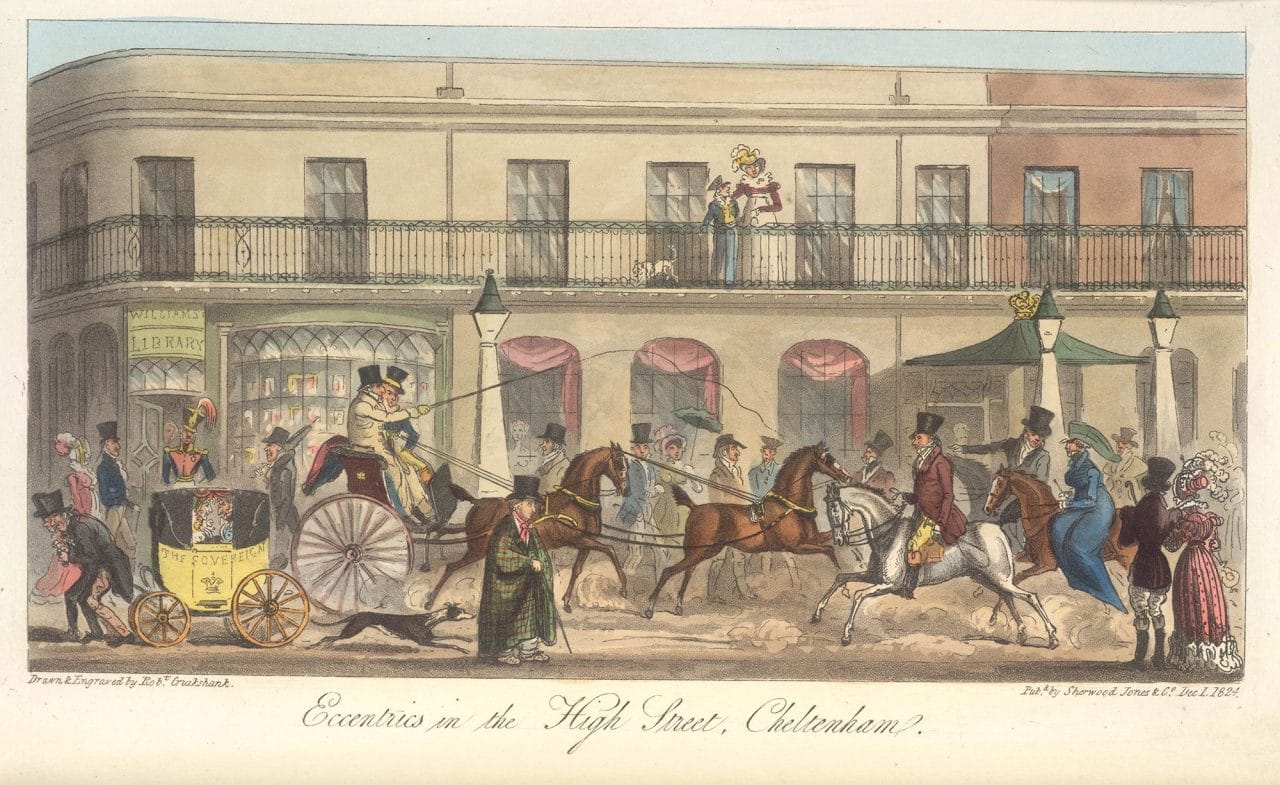

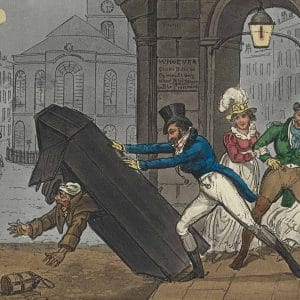

Cities streets echoed with the din of horse-drawn traffic clattering on cobblestones and the hubbub of people engaged in daily trade. Scores of hackney coaches cantered here and there while hundreds of carts transported goods back and forth. Sedan chairs weaved their way up narrow streets as they conveyed wealthy passengers to their places of business, while thousands of pedestrians hurried to and fro.

18th-century city life was frequently confusing and chaotic. The network of narrow allies and lanes, that had remained largely unchanged in many towns since medieval times, proved increasingly inconvenient to horse-drawn vehicles, and like today many cities were prone to traffic congestion. In 1749, for example, hundreds of people were stuck in a traffic jam on London Bridge that took nearly three hours to clear.

Crowds and people

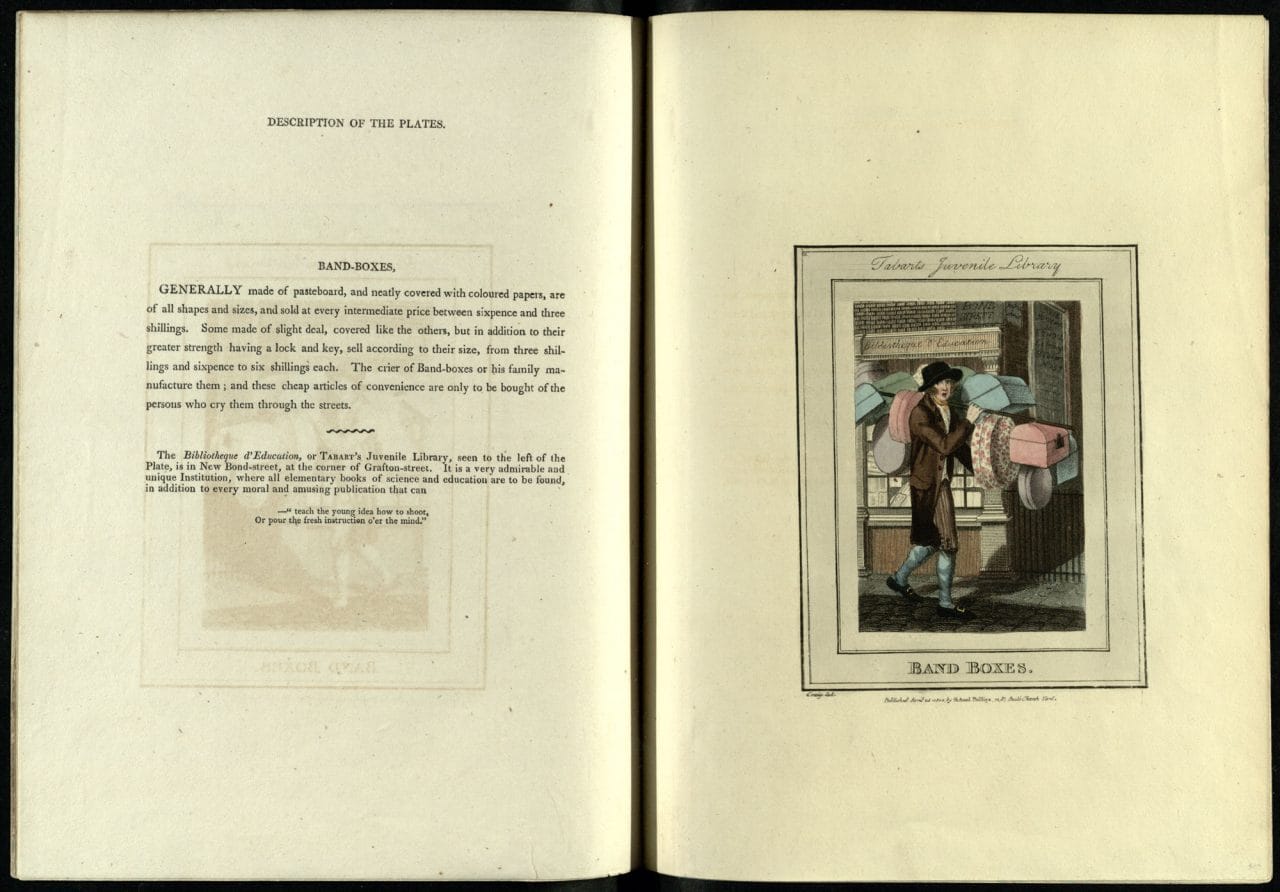

Rises in population added to the sense of confusion in many British cities. Crowds swarmed in every thoroughfare. Scores of street sellers ‘cried’ goods from place to place, advertising the wealth of goods and services on offer. Milkmaids, orange sellers, fishwives and piemen, for example, all walked the streets offering their various wares for sale, while knife grinders and the menders of broken chairs and furniture could be found on street corners.

People crowded around the windows of print shops displaying the latest satirical cartoons or waited outside lottery offices for results to be drawn. Others gathered to watch politicians make speeches at election time or to watch a bare-knuckle boxing match. House fires, accidents, fights and public executions, amongst an array of other urban spectacles, all drew huge audiences whenever they occurred, and added to the sense of excitement that was part of daily city life.

Conditions

Many 18th-century towns were grimy, over-crowded and generally insanitary places to be. London in particular suffered badly from dirt and pollution; so much so that candles were sometimes required at midday in busy shops owing to the smoggy conditions outside. Many travellers noted the ‘smell’ of London as they approached from far away, and letters received from the capital city were often said to have a ‘sooty’ odour.Alongside the stinking rivers and choking pollution of cities, open sewers ran through the centre of numerous streets. Gutters carried away human waste, the offal from butchers’ stalls and the tonnes of horse manure that were left daily on the streets. The roads of most towns and cities were unpleasantly dusty in the hot summer months and many became virtually impassable in the winter, owing to their muddy and flooded condition.

Street improvements

Towards the end of the century small steps were made to improve these conditions in cities. Several ‘paving acts’ were passed in London during the 1760s, for example, that resulted in the more efficient drainage and mending of roads, in order to keep local trade flowing. Regular street cleaning was implemented to ensure a clear passageway for traffic while hazardous shop signs overhanging streets were ordered to be removed.

Street lighting was also improved. From the middle of the 18th century oil lamps were more commonly used in many towns, paid for by householders out of local rates. By 1800 many visitors to London were mesmerized by the bright city lights they encountered there, which became the envy of most European cities.

Towns and city authorities also alleviated the huge problems of traffic congestion by laying out new roads and avenues. Towards the end of the century huge areas of decrepit housing were gradually cleared in order to make way for new turnpike toll roads, built to accommodate the ever-increasing levels of horse-drawn traffic.

The text in the article is published under a Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Matthew White

Dr Matthew White is Research Fellow in History at the University of Hertfordshire where he specialises in the social history of London during the 18th and 19th centuries. Matthew’s major research interests include the history of crime, punishment and policing, and the social impact of urbanisation. His most recently published work has looked at changing modes of public justice in the 18th and 19th centuries with particular reference to the part played by crowds at executions and other judicial punishments.