The violence of Romeo and Juliet

Romeo and Juliet is not only a love story. Andrew Dickson describes how the play reflects the violence and chaos of Shakespearean London – and how, more recently, directors have used it to explore conflicts of their own time.

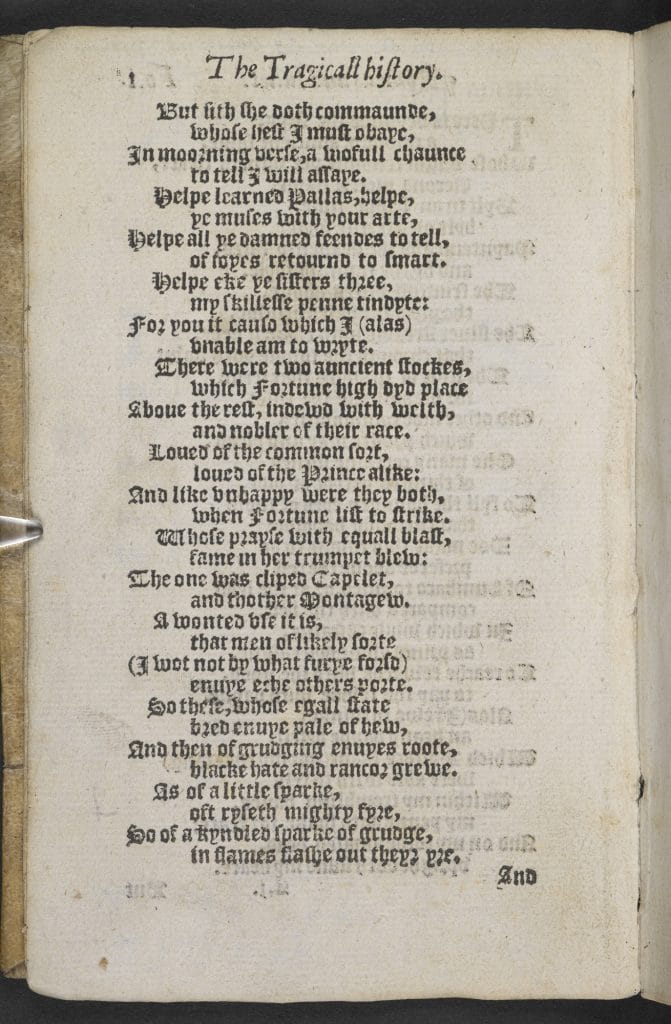

All Shakespeare’s plays contain themes that feel universal – the father who breaks disastrously from his children, the marriage that collapses under the pressure of a husband’s jealousy. But the ingredients that make up Romeo and Juliet are perhaps more universal than most: young love, bitter hate, feuding communities, tragic and undeserved death. Shakespeare drew his story of a pair of star-crossed Veronese lovers from the lumbering narrative poem Tragicall Historye of Romeus and Juliet by the Elizabethan writer Arthur Brooke, but in reality the idea could have come from almost anywhere. The story is surely as old as love itself.[1]

‘With great applause’

The play’s first audiences, perhaps at the Curtain Theatre in Shoreditch, seem to have responded powerfully to this story of volatile emotions and passions lived to the extreme: the first quarto of 1597 refers to it being ‘often (with great applause) plaid publiquely’, a claim echoed by the second quarto two years later, which refers to the play being ‘sundry times publiquely acted’.

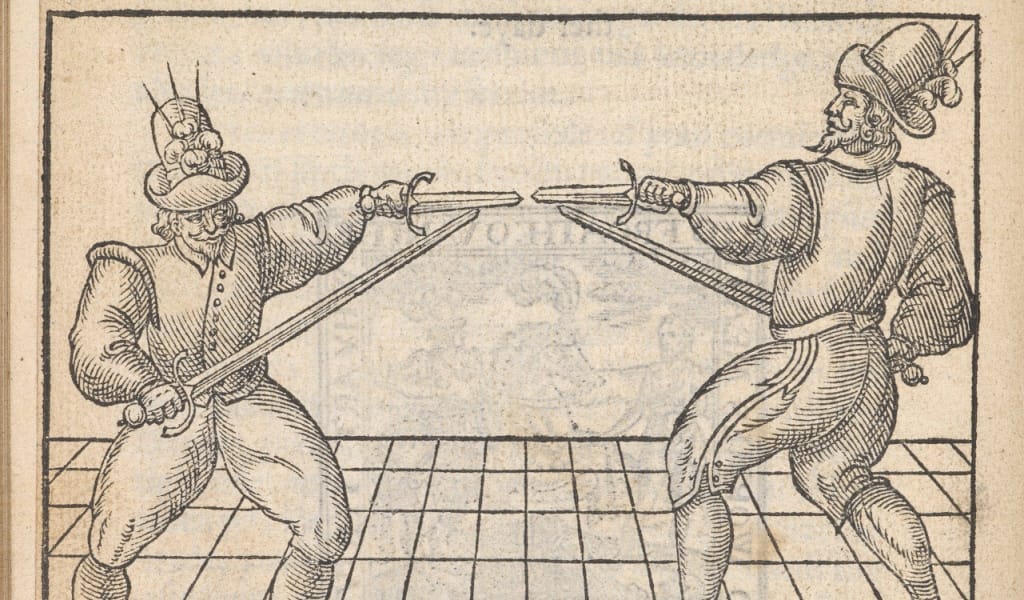

It is not hard to see why. Following Brooke, the play is set in Verona, but – as so often with Shakespeare – the streets we hear described on stage are also those of the bustling, overcrowded, pestilent, noisy and noisome city in which he lived and worked. London was a young city in the 1590s, and the crowds who took their chances with prostitutes and pickpockets in the entertainment districts were even younger; contemporary reports suggest audiences at the open-air theatres were predominantly male, and (unlike ‘private’ indoor playhouses, where admission cost at least six times as much) were drawn from all ranks of society. For this youthful, restless crowd – some of whom were bunking off work to attend – the violent skirmishes between the Capulets and Montagues that dominate the action must have been a major part of the attraction, and the swordfighting skills displayed by Shakespeare’s colleagues will have been watched with a keen eye. It is an amusing thought that for at least some of these artisans and apprentices, the lovers and their all-consuming passion might have seemed almost incidental.[2]

‘Mad blood stirring’

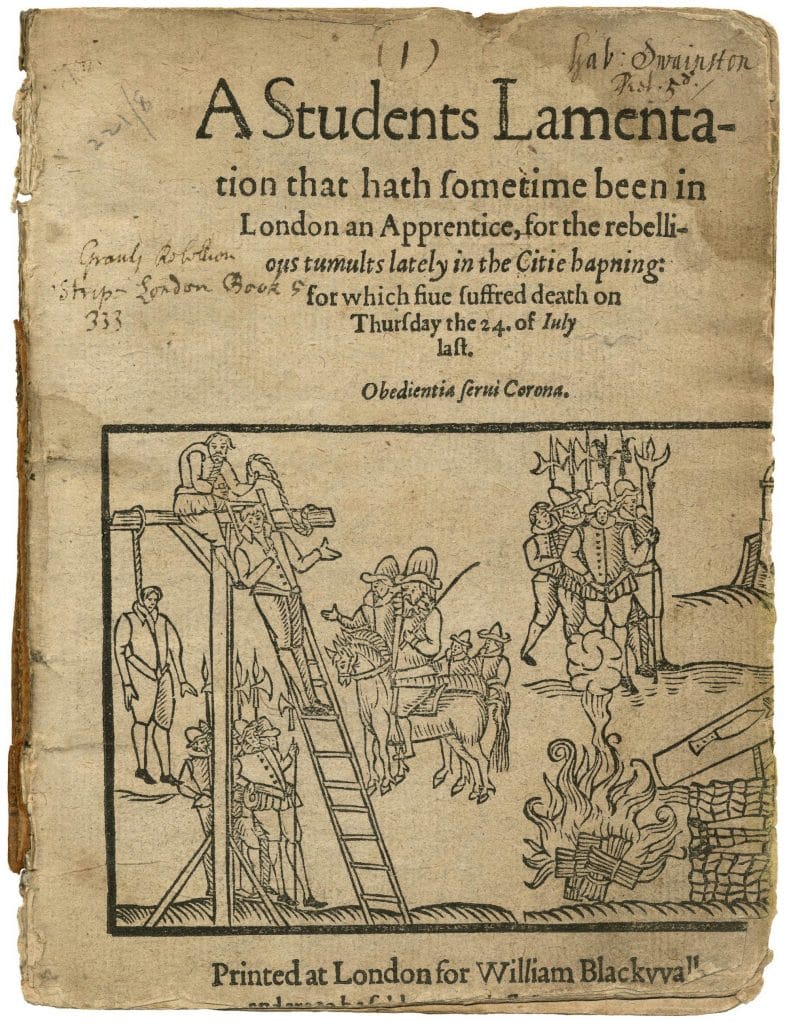

For greyer heads in the audience, the image of young men on the prowl and a city slipping into mayhem would have been only too familiar. In summer 1595, two years before that first quarto was printed and perhaps in the same year Shakespeare was writing the play, a series of riots in London over rocketing inflation caused the authorities to panic. On 29 June, a 1,000-strong army of apprentices and disaffected soldiers marched on Tower Hill; on 4 July, martial law was imposed. In the legal action that followed, the rioters were accused of intending to ‘robbe, steale, pill and spoile the wealthy … and to take the sworde of auchthorytye from the magistrats and governours lawfully aucthorised’.[3] Five were hanged, drawn and quartered. Ever-attentive to the world around him, Shakespeare responded to this atmosphere of what Benvolio calls ‘the mad blood stirring’ (3.1.4) by putting a version of it on stage:

GREGORY Draw thy tool. Here comes the House of Montagues.

SAMSON My naked weapon is out. Quarrel, I will back thee.

GREGORY How – turn thy back and run.

SAMSON Fear me not.

GREGORY No, marry – I fear thee!

SAMSON Let us take the law of our side. Let them begin.

GREGORY I will frown as I pass by, and let them take it as they list.

SAMSON Nay, as they dare. I will bite my thumb at them, which is a disgrace

to them if they bear it.

He bites his thumb

ABRAHAM Do you bite your thumb at us, sir? (1.1.31–42)

Audiences at early performances must have watched these exchanges with a nervous shiver, and wondered whether the couple in the play’s title would be the only ones caught up in the tragedy.

Prague to Palestine

And while Romeo and Juliet has barely been off stage or screen since – it may well be Shakespeare’s most performed and adapted play – it takes on a particular intensity in places and periods where violence is more than a mere literary device. In communist Czechoslovakia in 1963, Czech director Otomar Krejča directed it at the Prague National Theatre in a famous version that, drawing heavily upon its Cold War context, made it into a parable of disaffected youth versus negligent age (seeing it in Paris the following year, Peter Brook declared this ‘the best production of the tragedy he had ever seen’). Indeed, according to some theatre historians Romeo and Juliet was one of the most popular plays behind the Iron Curtain; at Moscow’s Vakhtangov Theatre in 1956, Josef Rapoport offered an image of the lovers crushed by violent social forces, an approach echoed by Tamás Major’s Hungarian production of 1971, which played the feud as an outright civil war, put down by an overbearing military regime.[4]

Other conflicts have provided divisions even starker and more dramatically potent. In 1994, the Romany company Pralipe (Brotherhood), forced to perform in exile from their native Macedonia, set the play in Bosnia with a Muslim Juliet and a Christian Romeo, and closed the play not with reconciliation but spatters of gunfire.[5] That same year, Palestinian and Israeli theatremakers came together to create a joint production in Jerusalem, with the Montagues as Arabs and the Capulets as Jews; the balcony scene was conducted in a mixture of Arabic and Hebrew, and the brawling families threw rocks in a deliberate echo of the intifada.[6]

In India, where tensions of creed and caste are impossible to ignore, the Romeo and Julietstory has inspired multiple versions, notably in cinema: in 1947, the year of partition, a version starring the great Indian heroine Nargis was released (the film is now unfortunately lost), while in 1992 an adaptation called Henna was a hit at the box office, featuring Zeba Bakhtiar as a Pakistani Muslim Juliet and Rishi Kapoor as her Indian Hindu lover.

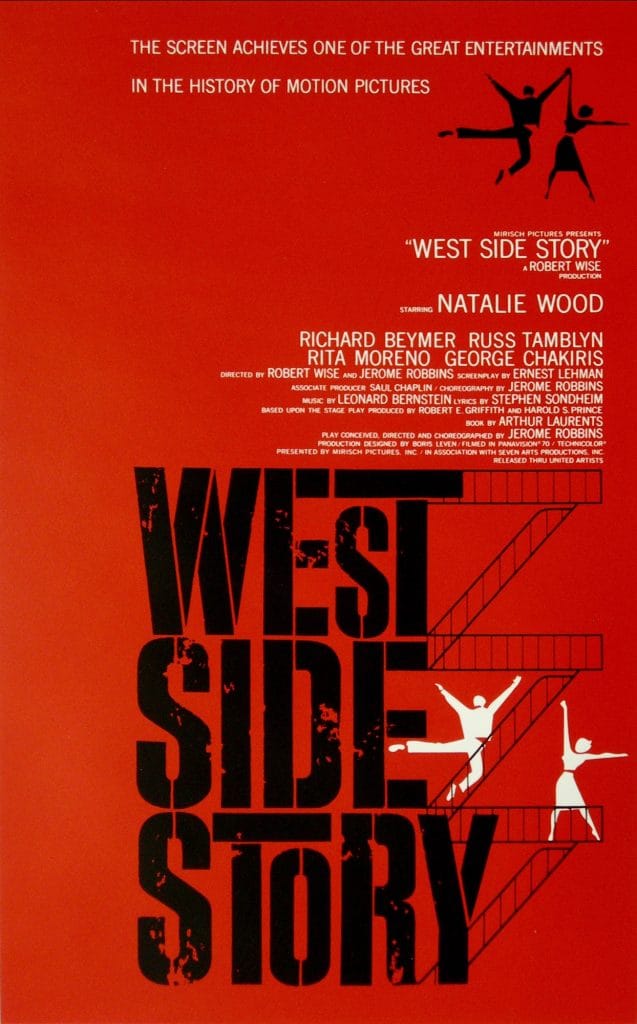

More familiar to most Western audiences is the much-loved West Side Story (1957), which united the considerable talents of Leonard Bernstein, Jerome Robbins and Stephen Sondheim. Set on the mean streets of New York’s Upper West Side, it portrayed the violent gang warfare between the Puerto Rican Sharks and the white Jets. That Robbins’s original concept suggested a conflict between Irish Catholic and Jewish families located in the entirely different community of the Lower East Side suggests how adaptable the story can really be.[7]

Yet if Romeo and Juliet can point up the multiple divisions in society, it can also – sometimes at least – attempt to heal them. In 2014, the Syrian playwright and director Nawar Bulbul, working with two groups of young people in Syria and Jordan, performed a version of the play unlike any other.[8] A 12-year-old Syrian boy played Romeo from the hospital in Amman where he’d been forced to flee; Juliet, her head covered with a veil and her identity kept secret, was in Homs. The two sets of performers – and the two sets of audience in each location – were rehearsed separately, then connected by Skype for the performance. Friar Lawrence was played by a young Muslim actor in tribute to Father Frans van der Lugt, a Jesuit priest murdered by the Assad regime. This time the play ended not with death, but in the frantic hope for something else. ‘Enough killing! Enough blood!’ Juliet’s companion cries, ‘Why are you killing us? We want to live like the rest of the world.’

脚注

- For Romeo and Juliet and its sources, see the introduction to G. Blakemore Evans’s revised New Cambridge edition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

- For a cross-section of Shakespeare’s audiences, see especially Andrew Gurr, Playgoing in Shakespeare’s London, 3rd edn (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008).

- ‘Attorney-general v. Blunt’, The National Archives: STAC 5/A19/23. Cited in Kristen Deiter, The Tower of London in English Renaissance Drama: Icon of Opposition (London: Routledge, 2008), pp. 92–97, which also provides a useful description of the rebellion.

- For an account of Krejča and other stagings behind the Iron Curtain, see Zdeněk Stříbrný, Shakespeare and Eastern Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), especially chapter 5, pp. 96–135.

- See Stříbrný, Shakespeare and Eastern Europe, pp. 141–42.

- See Liz Shulman, ‘Romeo and Juliet and the Politics of Occupation’, Mondoweiss, 5 February 2012

- A good account of the musical’s genesis is in Alvin Klein, ‘The Enduring Legacy of West Side Story’, New York Times, 15 May 1994

- See Preti Taneja, ‘Sweet Sorrow as Star-Crossed Lovers in Syria and Jordan connect via Skype’, The Guardian, 14 April 2015

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Andrew Dickson

Andrew Dickson is an author, journalist and critic. A former arts editor at the Guardian in London, he writes regularly for the paper and appears as a broadcaster for the BBC and elsewhere. His new book about Shakespeare’s global influence, Worlds Elsewhere: Journeys Around Shakespeare’s Globe, was published in 2015. He lives in London, and blogs at Worlds Elsewhere.