Women writers, anonymity and pseudonyms

In the late 18th and 19th centuries, writing as a profession was largely considered an activity unsuitable for women. Greg Buzwell explores the barriers and the lengths that women authors went to in order to publish their work.

Publishing novels and poems anonymously was once commonplace.

Between 1660 and 1750 approximately 50% of published prose fiction did not list an author on the title page, while a further 20% appeared under a pseudonym or tagline.[1] The percentage of novels published anonymously between 1750 and 1790 rose higher still, reaching over 80%.[2] Editorial convention, meanwhile, dictated that poems and reviews published in magazines usually appeared without attribution.

While some authors may have relished remaining in the background for reasons of modesty, notoriety or a fear of criticism, for many others it was purely a matter of convention. The use of pseudonyms around the same time emerged as an often-ironic subset of anonymity. Mary Robinson, the actress and mistress of the Prince of Wales (later King George IV), published poems as ‘Tabitha Bramble’ in the Morning Post, Tabitha Bramble being a sex-starved spinster in Tobias Smollett’s novel Humphry Clinker (1771).

The idea of an author being a figure of interest only really emerges with Romanticism in the late 18th century. Suddenly, a fascination with creative genius and literary celebrity propels writers such as Lord Byron, William Blake and Percy Shelley into the limelight. For women, however, the path to recognition and acclaim remained fraught with obstacles.

Late 18th- and early 19th-century women writers

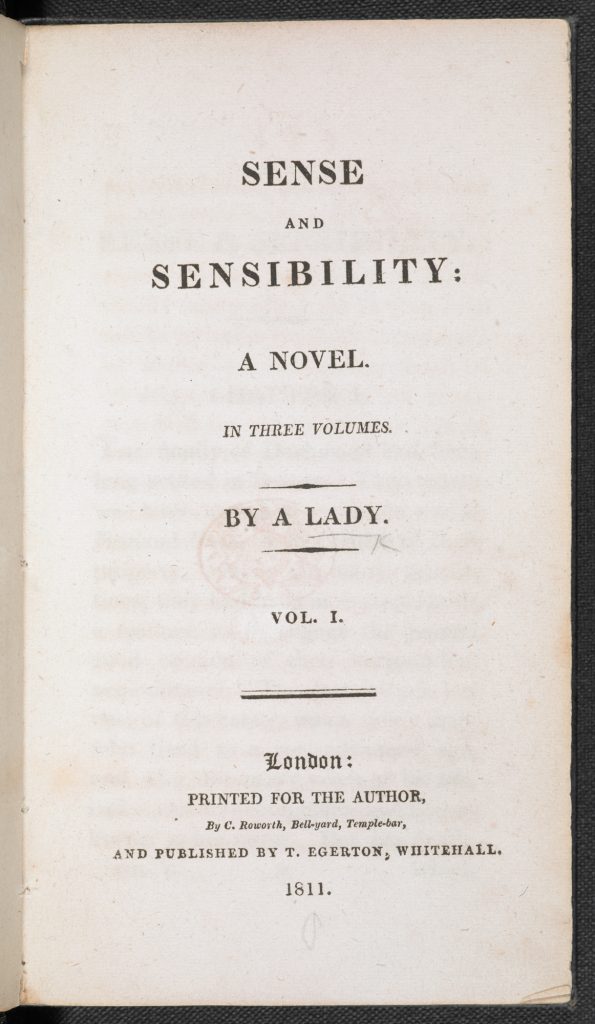

During the late 18th and early 19th century, writing, and especially the writing of fiction for money, was seen as a most unladylike activity. Unseemly parallels with prostitution arose regarding the notion of women writing novels which were then sold to anyone willing to pay. Derogatory terms such as ‘female quill-driver’ were common. Women from well-to-do backgrounds were not expected to pursue a career at all but rather to devote their efforts to making a good marriage. All the same, women read books, and they wrote them in large numbers. By the mid-18th century the tag ‘By a Lady’ became a common sight on title pages. This indicated not only the sex of the author but also that the book was by somebody of a certain class and thus suitable for perusal by respectable women.

Jane Austen’s first published novel, Sense and Sensibility (1811), appeared with the tag ‘By a Lady’. Her next, Pride and Prejudice (1813), appeared with the line ‘By the author of “Sense and Sensibility”’. Viewed from a 21st-century perspective it is deeply poignant to reflect that Jane Austen – one of our most loved and acclaimed authors – never saw her name on the title page of one of her books.

Her authorship of Sense and Sensibility, along with the novels that followed, only became widely known in December 1817 with the posthumous publication of Persuasion and Northanger Abbey. These novels appeared together with a ‘Biographical Notice of the Author’ by Jane Austen’s brother Henry, in which her authorship was revealed. Austen was far from alone in keeping her identity a secret. Her near-contemporaries, Maria Edgeworth, Ann Radcliffe, Frances Burney and Mary Shelley also published their early novels anonymously.

‘Literature cannot be the business of a woman’s life …’

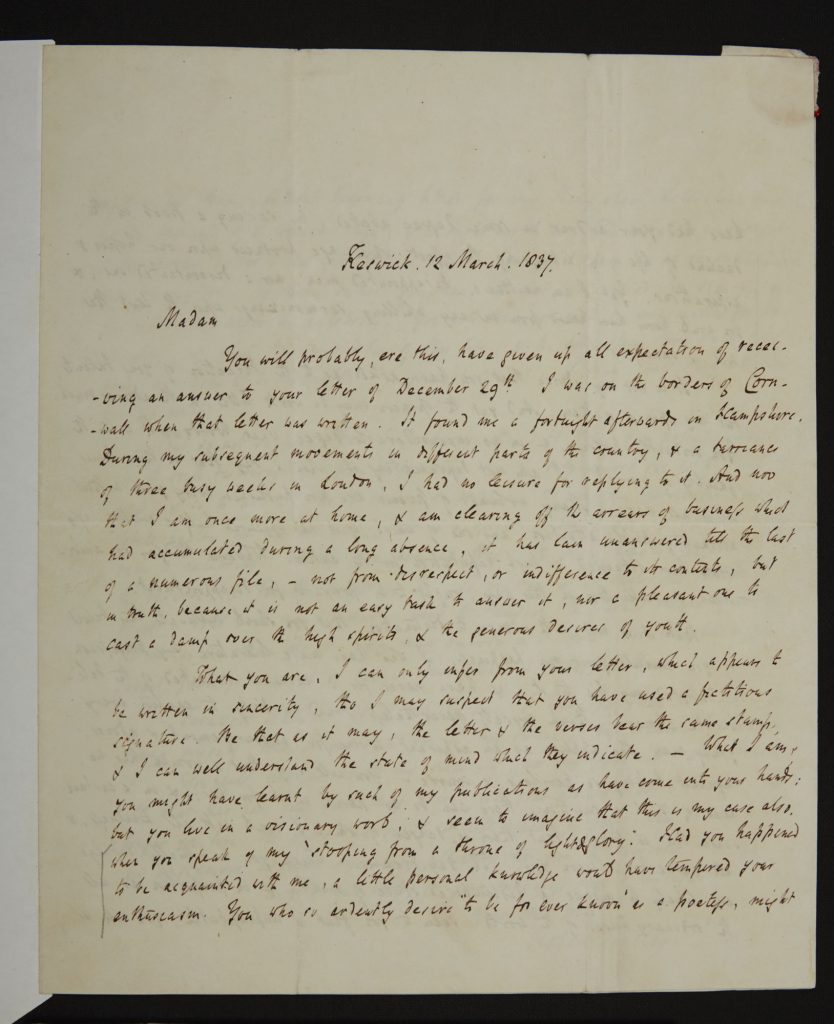

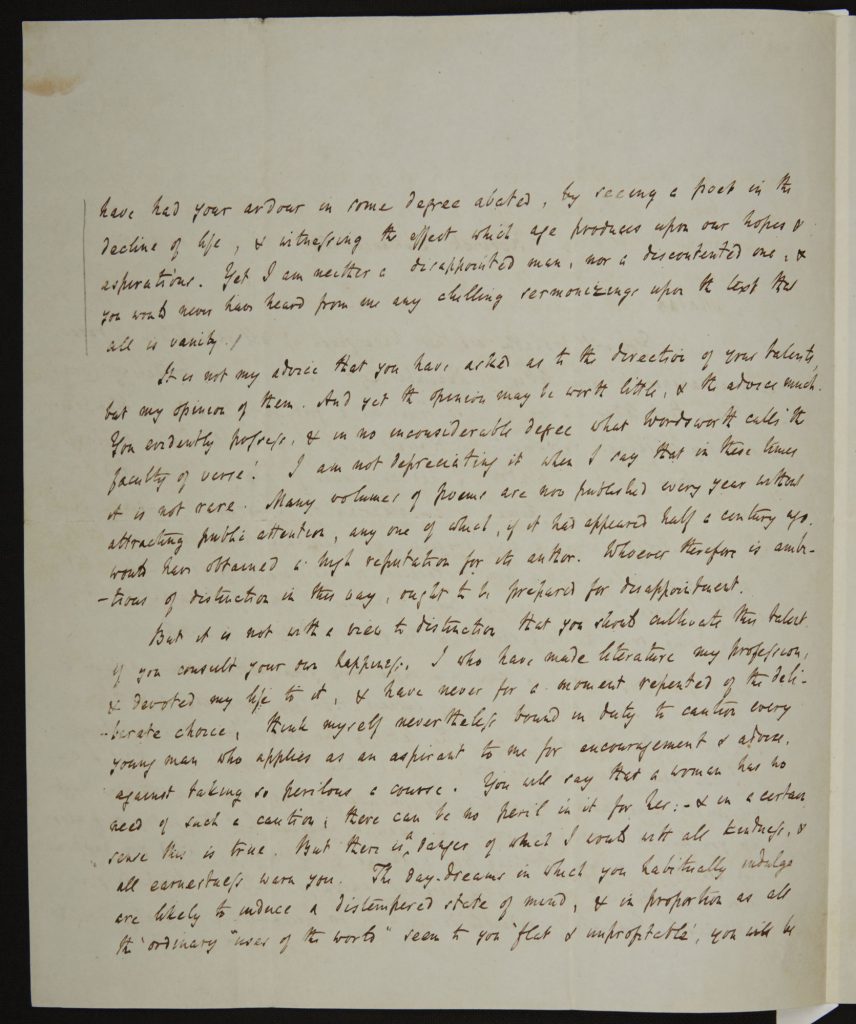

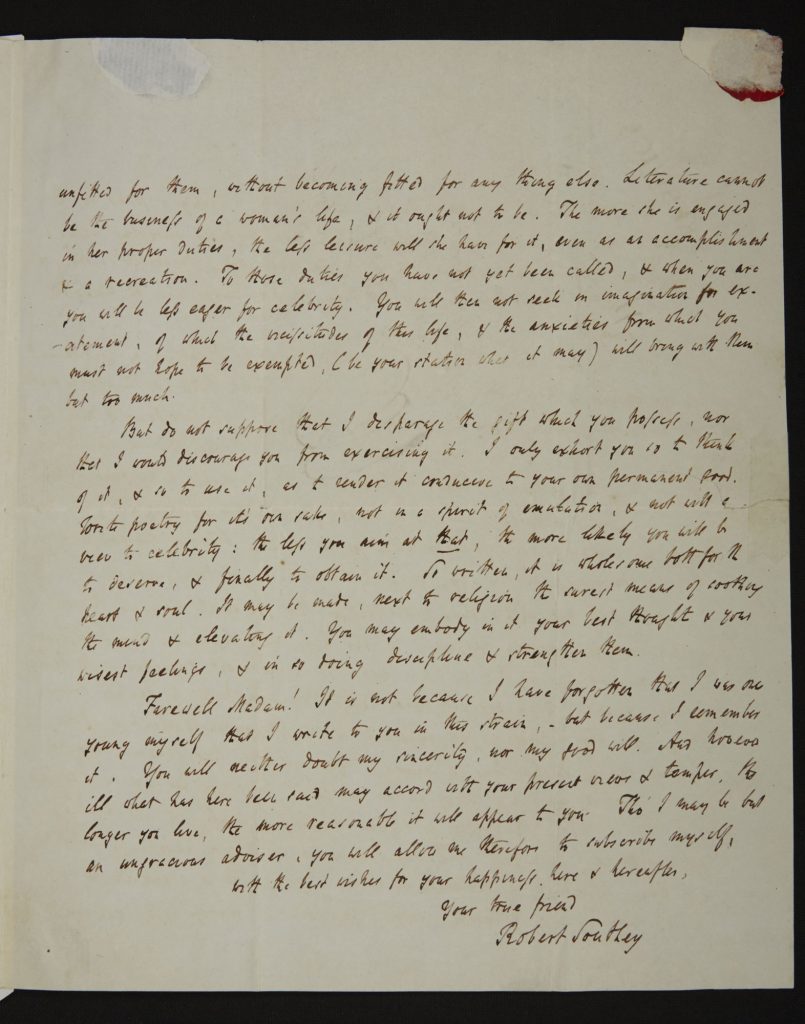

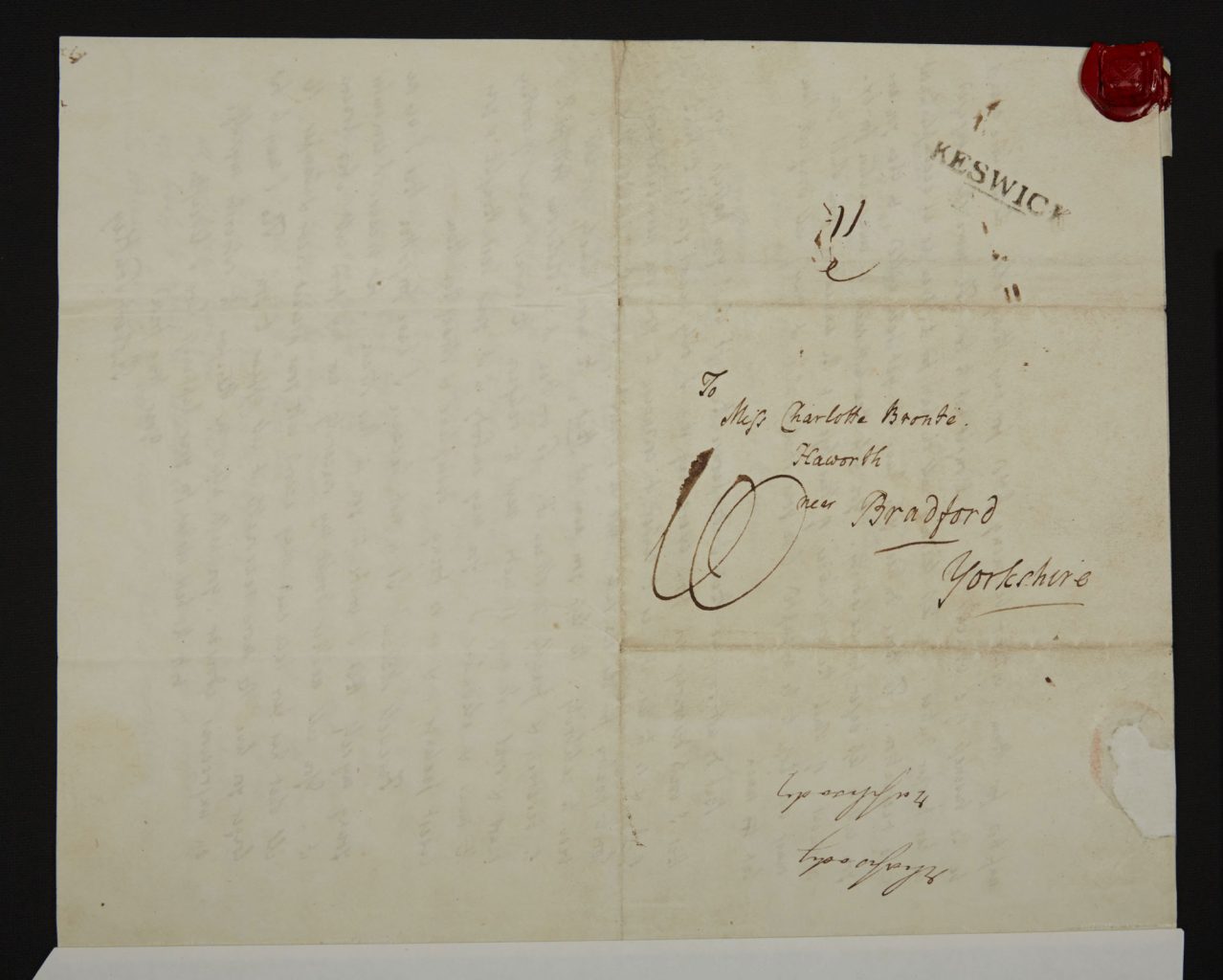

Ten years before the publication of Jane Eyre (1847) Charlotte Brontë sent a selection of her poems to the poet laureate Robert Southey for comment. Southey’s reply was far from encouraging. In his letter to Charlotte of 12 March 1837, he advised against the notion of women pursuing a career in literature, commenting ‘Literature cannot be the business of a woman’s life, and it ought not to be. The more she is engaged in her proper duties, the less leisure she will have for it even as an accomplishment and a recreation’.

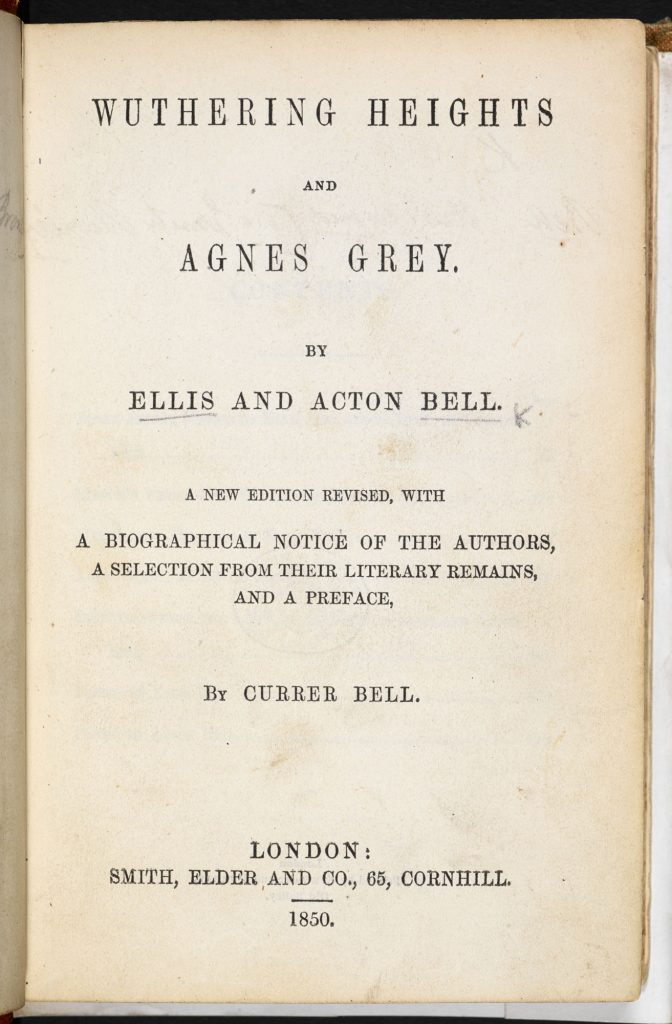

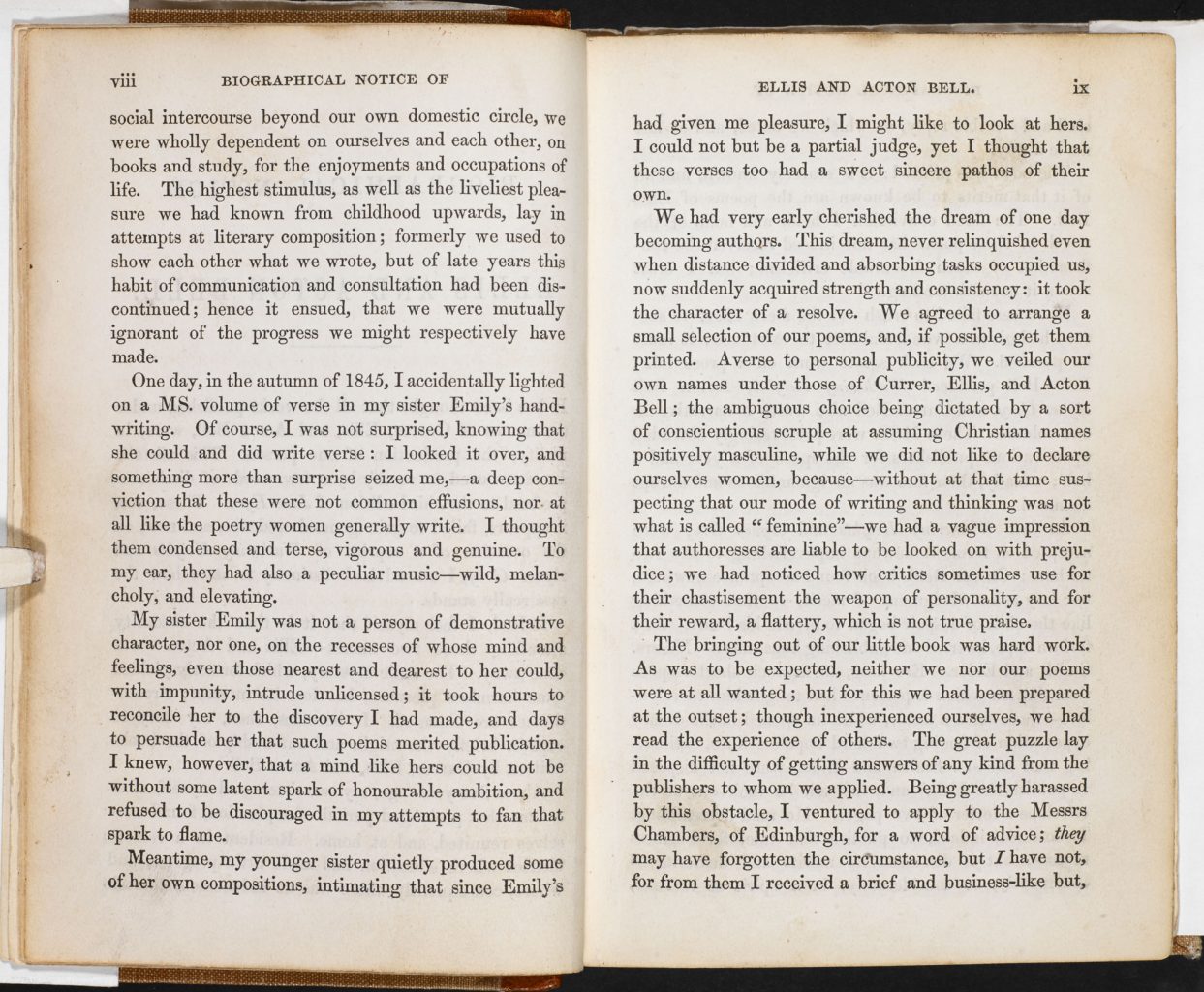

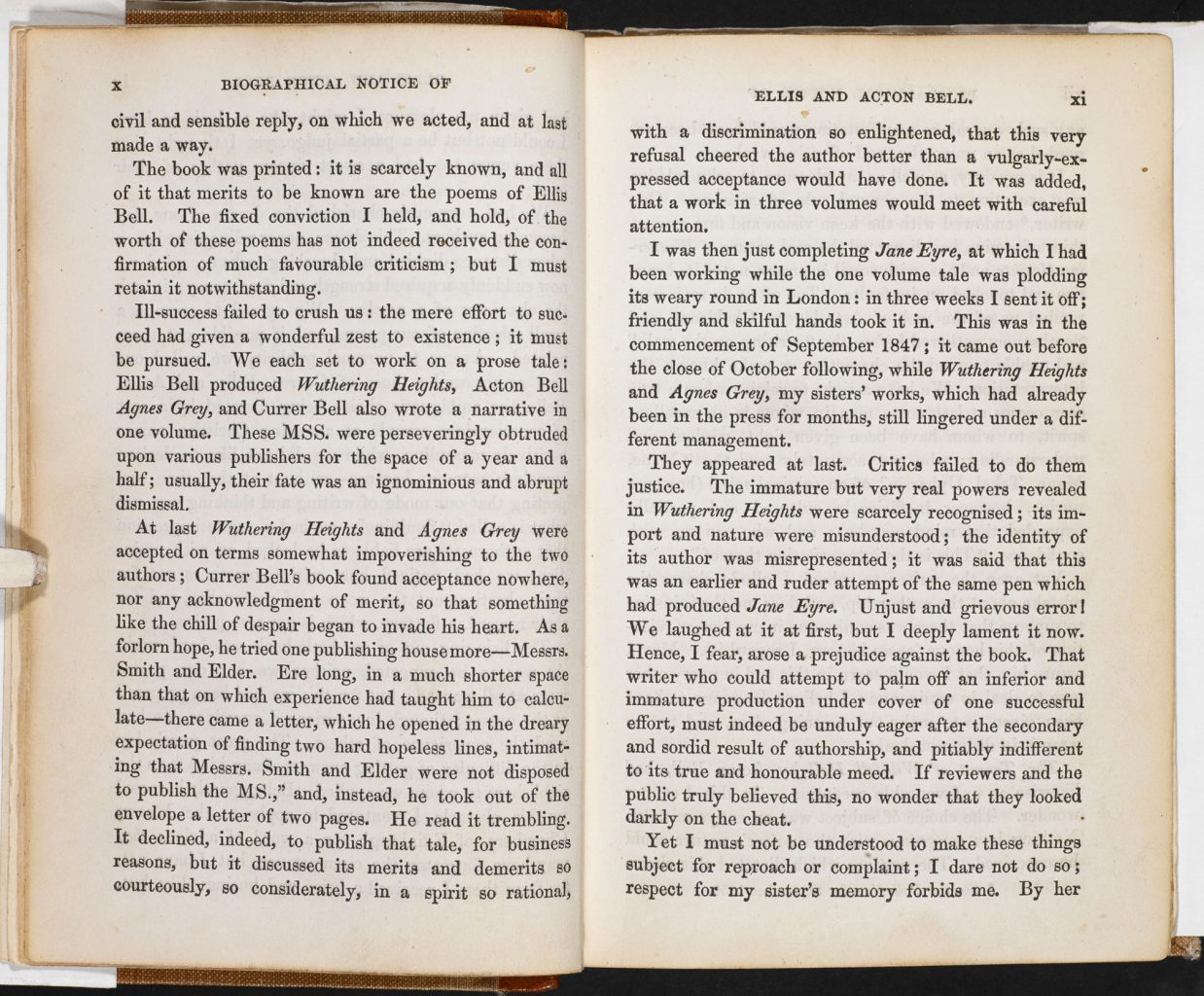

Hardly surprising then that in May 1846 when Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë published a collection of their poetry they did so under the pseudonyms Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell. In the preface to the combined 1850 edition of Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey Charlotte gave the sisters’ reasons for doing so:

Averse to personal publicity, we veiled our own names under those of Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell; the ambiguous choice being dictated by a sort of conscientious scruple at assuming Christian names positively masculine, while we did not like to declare ourselves women, because – without at that time suspecting that our mode of writing and thinking was not what is called ‘feminine’ – we had a vague impression that authoresses are liable to be looked on with prejudice; we had noticed how critics sometimes use for their chastisement the weapon of personality, and for their reward, a flattery, which is not true praise.

Preconceptions about novels by women

Mary Ann Evans, better known as George Eliot, voiced similar concerns. Her essay ‘Silly Novels by Lady Novelists’, published anonymously in the Westminster Review in 1856, criticises the frequently ludicrous plots of novels written by women: ‘Silly novels by lady novelists are a genus with many species, determined by the particular quality of silliness that predominates in them – the frothy, the prosy, the pious, or the pedantic. But it is a mixture of all these – a composite order of feminine fatuity, that produces the largest class of such novels, which we shall distinguish as the mind-and-millinery species’.

Eliot regarded such novels as undermining the cause of women’s education. The heroines are often educated, but this only renders them tedious and superficially witty rather than strong-willed and independent. The books also had the unfortunate effect of appearing representative of all fiction by women, meaning serious literary works were dismissed by many male reviewers as light-hearted romances before they had been read. In order to prevent her work being reviewed in this light, Evans published her first novel, Adam Bede (1859), under the pseudonym George Eliot. This allowed her book to be reviewed on its merits, rather than being judged on the author’s sex. It also served to shield her private life from scurrilous gossip – at the time of the novel’s publication, Eliot was in a relationship with the married philosopher George Henry Lewes.

The widespread misconception that scholarly work was the exclusive preserve of men resulted in many women publishing their work under male pseudonyms. Violet Paget, a pioneering feminist, essayist and author published under the name Vernon Lee. Katharine Bradley and her niece and partner Edith Cooper published their poems under the name Michael Field. In 1884, when Bradley was 38 and Cooper 22, they published, as Michael Field, their first work Callirrhoë to critical acclaim. In the same year Bradley wrote a letter to their friend and mentor Robert Browning in which she asked him not to reveal their identity, ‘the report of lady-authorship will dwarf and enfeeble our work … [W]e have many things to say the world will not tolerate from a woman’s lips’.[3]

Recovering Hidden Histories

In her essay A Room of One’s Own (1929), Virginia Woolf summed up the injustices faced by women writers and argued for a fairer future. She commented: ‘I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman’.[4] She also summarised the plight of writers such as Charlotte Brontë when she observed: ‘Currer Bell, George Eliot, George Sand, all the victims of inner strife as their writings prove, sought ineffectively to veil themselves by using the name of a man. Thus they did homage to the convention, which if not implanted by the other sex was liberally encouraged by them (the chief glory of a woman is not to be talked of, said Pericles, himself a much-talked-of man) that publicity in women is detestable’.[5]

For Woolf the recovery of the lives and works of women writers who had gone before, and the establishment of a female literary tradition was vitally important. Woolf argued that ‘we think back through our mothers if we are women’.[6] Each generation of women writers builds upon the successes of those who have gone before, and for that to be possible the lives of those women need to be known and their books read, studied, valued and enjoyed.

Today, the challenges facing women writers have changed. In the 1970s publishers such as Virago began returning books by neglected women authors to the literary canon. Representation is now very much a concern, and ensuring that women from ethnic minorities have their work read, reviewed, promoted and marketed on a level playing field with their white peers is increasingly important. The more perspectives we encounter the richer our understanding of life.

Even so, while publishing anonymously is now rare, the use of pseudonyms continues, as does the use of initials which disguise the gender of an author. When Bloomsbury Children’s Books published Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone in 1997 the book appeared as by ‘J K Rowling’ – it being feared that publishing as ‘Joanne Rowling’ would alienate young male readers.[7] Wishing to publish the first in a series of detective novels some years later, and keen to let the books stand on their own merits, Rowling chose the male pseudonym Robert Galbraith.

Novels by men and women, one would hope, are now judged, read and enjoyed on merit rather than on the gender of the author, but certain genres are still viewed as being primarily for men (action thrillers, say) or women (romance, for example). Perhaps it is in breaking down these stereotypes that the next challenges await.

脚注

- Leah Orr, ‘Genre Labels on the Title Pages of English Fiction, 1660–1800’, Philological Quarterly, 90.1 (2011), pp. 80–81.

- James Raven, ‘The Anonymous Novel in Britain and Ireland, 1750–1830’, in Robert J. Griffin (ed.) Faces of Anonymity: Anonymous and Pseudonymous Publication from the Sixteenth to the Twentieth Century (New York: Palgrave, 2003), p. 145.

- Katherine Bradley and Edith Cooper, Michael Field, The Poet, ed. by Marion Thain and Ana Parejo Vadillo (Toronto: Broadview, 2009), p. 311.

- Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own and Three Guineas (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), p. 38.

- Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own and Three Guineas (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), p. 38.

- Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own and Three Guineas (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), p. 75.

- J K Rowling, 2016.

(accessed 21 July 2020).

撰稿人: Greg Buzwell

Greg Buzwell is Curator of Contemporary Literary Archives at the British Library. He has co-curated three major exhibitions for the Library – Terror and Wonder: The Gothic Imagination; Shakespeare in Ten Acts and Gay UK: Love, Law and Liberty. His research focuses primarily on the Gothic literature of the Victorian fin de siècle. He has also edited and introduced collections of supernatural tales by authors including Mary Elizabeth Braddon, Edgar Allan Poe and Walter de la Mare.