Childhood and Children’s Literature

This collection introduces and explores the captivating world of children’s literature from its origins up to the early 20th century. From the moralising tales of the early 17th century to the advent of illustration; from nursery rhymes and enthralling fairy tales to poignant orphan narratives and haunting school stories that instigated essential social reforms; and from exciting adventures and fantasies to diverting books of nonsense and engaging animal stories.

Morals and manners

In the early 17th century few books were aimed specifically at children. Texts for youngsters were moralising in content and tone, condemning sinfulness and promoting virtue. It was widely believed that children were born in a state of ‘original sin’, and their souls needed to be ‘cleansed’ for them to achieve salvation. James Janeway’s A Token for Children, being an Exact Account of the Conversion, Holy and Exemplary Lives, and Joyful Deaths, of several young Children (1671–72) was a famous work of this period. A total of 13 children die in its pages. Robert Russell’s A Little Book for Children (1693–1696) urged ‘Wicked Children’ to behave correctly and ‘to resist the temptations of the Devil’. The titles and subject matter sound dull and daunting to modern readers, but there is documentary evidence that they were genuinely enjoyed.

查看更多Pioneers

Pioneering authors wanted their writing to be entertaining, as well as didactic. From around 1730 Thomas Boreman specialised in children’s books, and produced the intriguing miniature volume The Gigantick History of the two Famous Giants and other Curiosities in Guildhall, London (1740), and Curiosities in the Tower of London (1741) which contained woodcuts and descriptions of animals to be found in the Tower zoo. The prolific 18th-century publisher John Newbery produced books that were immediately attractive to children: his publications were issued in a small format, with illustrations and bound in brightly coloured flowered paper. The first edition of his A Little Pretty Pocket Book (c. 1744) states on the title page that the book was ‘intended for the instruction and amusement of little master Tommy and pretty Miss Polly. With two letters from Jack the Giant-killer: as also a ball and pincushion; the use of which will infallibly make Tommy a good boy, and Polly a good girl’.

查看更多Reason and Romanticism

John Locke’s influential treatise of 1693, Some Thoughts Concerning Education, advised that children should be guided by reason rather than dire threats of punishment. Locke’s emphasis was on preparing the child for adulthood; however, more than half a century later this view was challenged by Jean-Jacques Rousseau in Émile (1762). With his child-centred approach, he paved the way for the Romantic poets, who proclaimed that children were special precisely because they were uncorrupted and had a precious affinity with nature. Rousseau believed that youngsters should develop unfettered by adult conventions, and be able to express themselves freely.

查看更多The glorification of childhood is a dominant aspect in the work of Romantic poet William Blake. He championed the cause of children, writing about them and for them with compassion, and deliberately subverting instructional literature when he wrote Songs of Innocence and Experience. Blake engraved his poems on an illustrated background, and also designed and engraved six plates for Mary Wollstonecraft’s Original Stories from Real Life (1791), a work intended as a model for teachers and pupils. The positive qualities of childhood were praised by Blake: lack of sophistication, honesty, playfulness, goodness and minds untainted by the adult world. His line of thought paved the way for the 19th-century ‘cult of childhood’.

查看更多Books with child leads: foundlings and orphans

Most people know what it is like to experience childhood insecurities and a sense of alienation, and it is easy to understand why readers through the centuries have empathised with characters in orphan stories. Abandoned children appear in the earliest Western myths and fairy stories (think of Moses rescued from the Nile, and Romulus and Remus adopted by a she-wolf). Their prospects may seem dismal, but in fiction their potential is boundless, and while we endure their sufferings vicariously, we are intrigued to see where they will settle and who they will become.

查看更多Orphan narratives became a subgenre of children’s literature in the late 1700s. In 1765 John Newbery published a popular book, The History of Little Goody Two-Shoes, about an orphan girl called Margery who is obliged to negotiate her way through life, encountering problems and dangers. Seventy years later, Charles Dickens created perhaps the most famous orphan in English literature: Oliver Twist, who is shown navigating his way through a squalid and criminal-infested London. Here, and in many of his other novels, from David Copperfield and Bleak House to Great Expectations and Our Mutual Friend, Dickens’s orphan heroes became the lenses through which readers could glimpse the grim realities of 19th-century England.

查看更多Jane Eyre and the rebellious child’s perspective

Moral instruction books generally depicted naughty children as bad role models, who needed to acknowledge the error of their ways. In contrast, orphan narratives about vulnerable victims readily won the sympathy of readers. Although Charlotte Brontë chose an orphan as her protagonist, her finely nuanced portrayal in Jane Eyre (1847) introduced a new kind of heroine. She imbued Jane with a transgressive streak, which distressed a number of contemporary critics. They felt that rebellious attitudes and disruptive conduct contravened the normal standards of feminine behaviour, posing a threat to the social order at a time of working class uprisings in Britain and momentous political upheavals in Europe.

查看更多Here was a heroine who articulated her defiance in the face of tyranny, and,whose outbursts deserved to be endorsed. Significantly, Brontë’s tale has a first-person narrator: Jane was permitted an authentic voice to tell her own story. This intimate, accessible approach encouraged reader engagement and empathy, and the novel invited greater understanding of children’s thoughts and feelings.

查看更多School stories

Generations of children have fantasised about life in British boarding schools, from Mallory Towers to Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. With parents out of the picture, these schools are prime settings for coming-of-age tales of intense friendships, bitter rivalries and midnight feasts. However, boarding schools in the 18th and 19th centuries – in literature and in life – were often brutal places. In Jane Eyre (1847) Lowood Institution was modelled on the Clergy Daughters’ School, where Charlotte Brontë had been a pupil. She conveys the harsh regime, the appalling living conditions, puritanical teaching methods and severe punishments. Brontë’s graphic account prompted calls for reform. Eight years earlier Charles Dickens had described an even grimmer establishment, Dotheboys Hall, in Nicholas Nickleby (1839); the headmaster and owner, Wackford Squeers, is not remotely interested in the welfare of the boys entrusted to his care. His concern is to make money, but he is also motivated by a deep sadistic streak. Dickens based his novel on research, and his depiction led to the closure of many

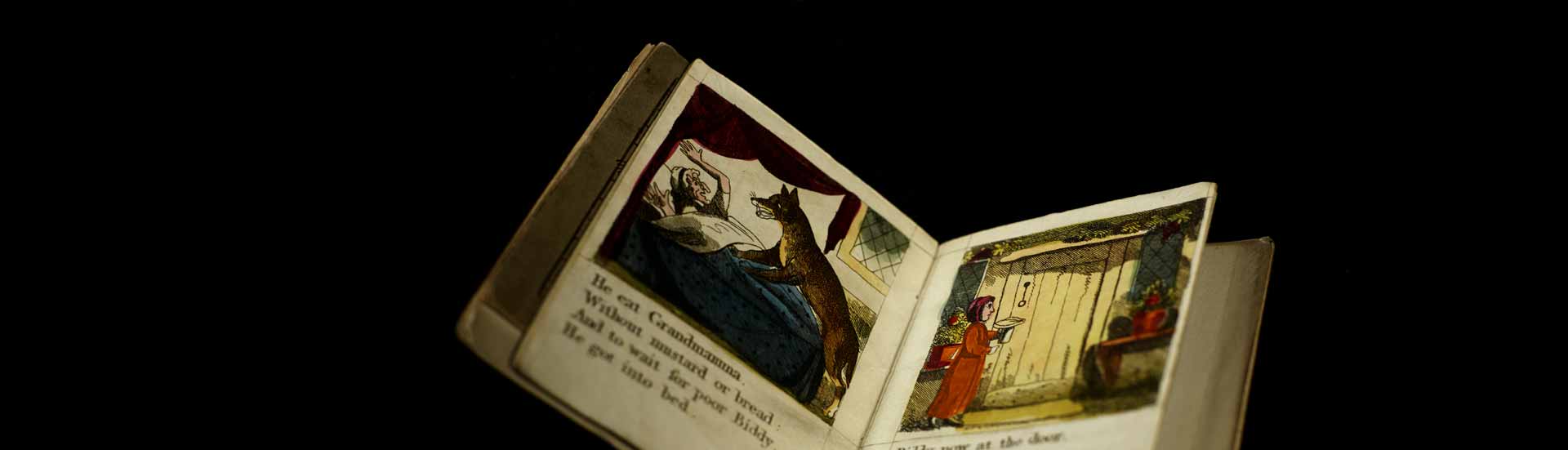

查看更多Fantasy and fairy tale

Enchanting fairytales by the brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen were first translated into English in 1823 and 1846 respectively, helping to pave the way for a ‘golden age’ of children’s literature. The increasing allure of the fantasy genre in the 19th century may have been a reaction to significant historical changes: industrial and urban developments made readers thirsty for an antidote to the pressures of the modern world. Authors obliged, producing a wide range of experimental, stimulating, enjoyable texts for children. They avoided didacticism by playfully firing children’s imaginations and suspending the rules of reality for a time. Even so, elements of moral instruction were not precluded from fantastical works: Charles Kingsley’s The Water Babies (1863) has a moral agenda, critiquing child labour and the mistreatment of the poor; and in Oscar Wilde’s story The Selfish Giant (1888) adults learn from children. Fantasy tales and social realism could co-exist comfortably and successfully.

查看更多Logic, limericks and nonsense

Edward Lear published A Book of Nonsense in 1846, to immediate acclaim. He was a talented artist, and complemented his engaging verse with appealing illustrations. A later work, Nonsense Songs, Stories, Botany and Alphabets (1871), contains the much-loved poem ‘The Owl and the Pussycat’. Word-play is a key feature of the genre, and Lear delighted readers with his invented words as in the wonderfully evocative description of ‘a runcible spoon’. Lewis Carroll too found enduring success with his wonderfully nonsensical Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865). The author borrowed techniques and ideas from nursery rhymes and folk tales, interlacing them with games, riddles, puzzles and wordplay in an absorbing narrative. Alice is given the opportunity to challenge social conventions and question adults’ behaviour and attitudes. This approach was hugely liberating and entertaining for young readers.

查看更多Animals and anthropomorphism

Animals, birds, fish and insects appear in many children’s books, and are often depicted symbolically with human characteristics. The device has a long tradition: Aesop’s Fables spring to mind. In Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), spurred by curiosity, Alice pursues the elusive, fretful White Rabbit, and becomes flustered by the brusque, pipe-smoking Caterpillar. Ultimately, however, her encounters with such creatures teach her valuable lessons about growing up in an uncertain world. Lewis Carroll’s success was emulated by Kenneth Grahame, in The Wind in the Willows (1908), and in Beatrix Potter’s books (published 1902–12). When writers use anthropomorphism they deliberately distort reality, for a range of reasons. There may simply be a desire to entertain, to be playful and encourage imaginative responses. However, the history of children’s literature demonstrates that authors often use anthropomorphism didactically. Readers reflect upon their own behaviour and attitudes, and anthropomorphic books may address serious social issues. Furthermore, if a message is particularly painful and upsetting, a degree of emotional distance is provided – a ‘safety net’. Literary anthropomorphism enables writers to open up engaging dialogue with their readers.

查看更多The Just So Stories and modern morality

For centuries, morality tales have reflected the contexts in which they were written. Many 19th-century children’s books endorsed the prevailing ethos of imperialism. At a time when Western ideals were being imposed upon people of other cultures, authors tended to convey particular values and assumptions, sometimes consciously, sometimes unconsciously. Animal stories of the period often featured non-European species, which enhanced their appeal. Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936) was born in Bombay, when India was part of the British Empire. His Just So Stories (1902) were written for the delectation of his own children, and have evocative, intriguing titles, including ‘How the Camel Got His Hump’, ‘How the Leopard Got His Spots’ and The Cat That Walked by Himself’. The style is intimate, wonderfully inventive, and charmingly entertaining. However, whilst the tales have remained popular, Kipling’s reputation has varied in different periods. He has been judged as a politically controversial figure and accused of jingoism. Critical debate will, no doubt, persist. Fortunately, children’s literature will continue to inform, delight and inspire. It is a constantly evolving genre, ripe with inexhaustible potential.

查看更多