Crime and Crime Fiction

Why was crime such a popular subject in 19th-century fiction? How did literature balance fear, social commentary and entertainment? This theme traces the development of crime fiction from penny dreadfuls’ and the Victorian criminal underworld through to the enduring popularity of Sherlock Holmes.

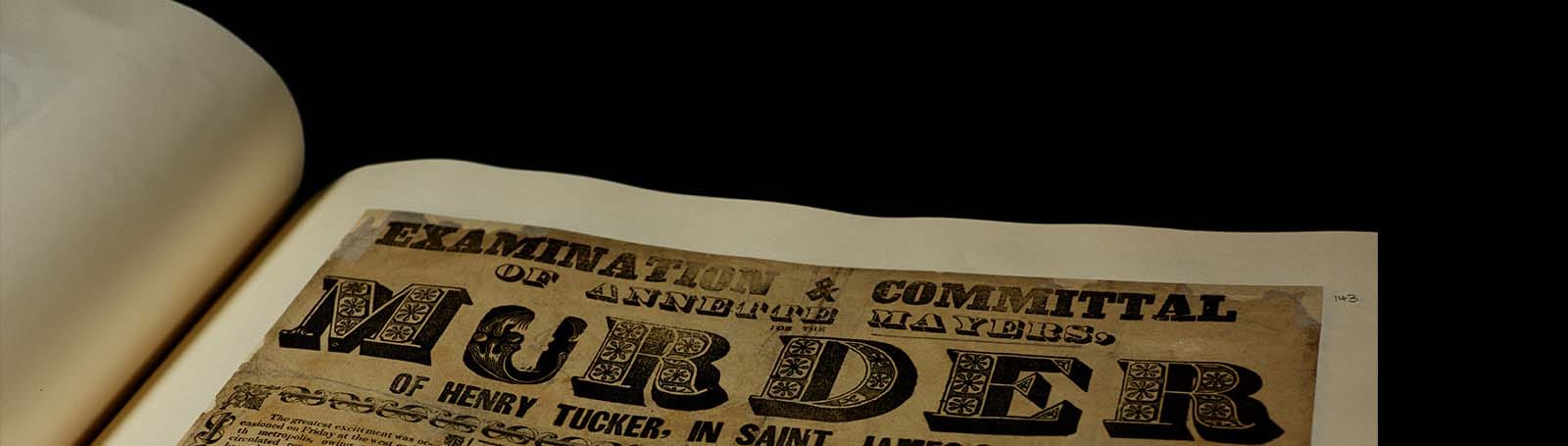

Sensationalised crime

In the early 19th century, as urban populations swelled, British cities became hotbeds of squalor, corruption and vice. Labyrinthine streets and ramshackle housing, rich and poor living cheek by jowl, smog and anonymous crowds, all created the ideal environment for crime to thrive. Newspapers, novels, short stories, posters and ballads, published in greater quantity than ever before, picked up on the public’s mingled fear and fascination with urban crime. Pages were filled with lurid accounts of acts of violence and depravity. With Gothic fiction on the rise and sensational stories in the news, the stage was set for the appearance of a new genre crime fiction.

查看更多The rise of detective fiction

The Metropolitan Police Force of London was established in 1829 after a protracted 17-year-debate on how best to control and protect the growing population. Until then the law had been enforced, with varying degrees of efficiency, by unpaid constables and watchmen. A specialised ‘Detective Department’ was founded in 1842, catching the attention of the novelist Charles Dickens, who wrote articles in enthusiastic praise of the Department. Soon afterwards, Dickens created the first ever fictional detective: Mr Bucket in Bleak House (1852–3), based on a real detective-inspector, Charles Field. Whilst investigating two mysteries (finding the real identity of an orphan and solving a murder), Bucket comes to realise that the two cases are linked. Toward the end of the novel, he reveals that he has solved the case and carefully explains his deduction. This was the first time that this classic revelation scene had been used in English literature.

查看更多'Penny dreadfuls'

By the 1830s literacy was on the rise, and advances in printing made it possible to produce cheap fiction for the mass market. A new format of serialised fiction was born that soon became a publishing phenomenon: the ‘penny dreadful’. The ‘dreadful’ part derived from the tendency of such works to dwell on murder, robbery and the unsavoury side of urban life. The ‘penny’ in the title refers to the price of each instalment. The first penny dreadfuls tended to be influenced by the popular Gothic fiction of the pre-Victorian era – featuring gypsies, pirates and romantic adventure – but gradually the focus turned to tales of true-life crime, and later true-life detection.

查看更多Murder as entertainment

Executions were still held in public in the Victorian period and often attracted crowds of thousands – the travel agency Thomas Cook even ran excursion trains to these spectacles. In 1849, Charles Dickens, along with 30,000 other spectators, watched the hanging of man and wife Frederick and Maria Manning, a notorious pair of murderers. Appalled by what he saw, Dickens sent a letter of complaint to The Times, arguing that it was inhumane to conduct executions in public. Despite Dickens’s intervention it was another 20 years before hangings would be held within prison walls. Dickens’s preoccupation with capital punishment can be seen in many of his works, from Great Expectations to Oliver Twist.

查看更多Crime and poverty in Oliver Twist

Dickens’s Oliver Twist draws a horrifyingly vivid picture of London’s criminal underworld; the intention was to fascinate his readers but also to question the morality of that fascination. Dickens was particularly keen to show his readers the ‘truth’ about the poverty at the heart of 19th-century cities, desperate conditions which forced many into a life of crime.

查看更多Dickens was appalled to find that, contrary to his intentions, Oliver Twist was lumped in with the popular romanticised tales of criminal life known as ‘Newgate Novels’. These fictions glamorised the exploits of notorious criminals and were believed to encourage vice. Dickens responded in his 1841 Preface to Oliver Twist, arguing that his novel’s ‘miserable reality’ was intended as a deterrent. However, the author understood the power of sensationalism and wanted to move his readers to compassion, and if possible action. To make this message more effective, he refracts his portrayal of ‘true’ life through the lenses of melodrama, Gothic fiction, satire, sentiment and allegory. Throughout, aspects of different genres are skilfully woven together to enhance the power of the writing, maintain reader interest and move the audience to tears and laughter.

查看更多Jack the Ripper

In autumn 1888, five women in the east London slums of Whitechapel died at the hands of an unknown man. The murderer became known as ‘Jack the Ripper’, a now legendary name that still haunts London’s streets today. The police failed to identify the murderer, and were mercilessly ridiculed by the satirical press. These events fascinated the country: in the four years after the last murder the Illustrated Police News somehow still managed to get 184 front-page stories out of the scandal.

查看更多<em?The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

Two years earlier, Robert Louis Stevenson had published his now iconic novella The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, in which a highly respected doctor creates a potion to transform himself into a degenerate, murderous monster. Stevenson’s depiction of a criminal lurking behind an acceptable public persona rendered Jekyll and Hyde a particularly disturbing work during the late 1880s, just as Jack the Ripper was carrying out his attacks in Whitechapel.

查看更多The world's greatest detective

The culmination of crime fiction undoubtedly came with the creation of Sherlock Holmes. Introduced to the world as an ‘unofficial private detective’ in A Study in Scarlet (1887), Holmes remains to this day the most famous detective in literary history. His art of logical deduction, forensic analysis and elimination to reach the truth are now iconic characteristics of the genre. The extreme popularity of the pipe-smoking detective marks a significant shift of focus in crime fiction: readers were no longer captivated by the criminals but by the investigator; so much so that his ‘death’ in ‘The Final Problem’ caused a public outcry, forcing his reluctant creator Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to resurrect him.

查看更多