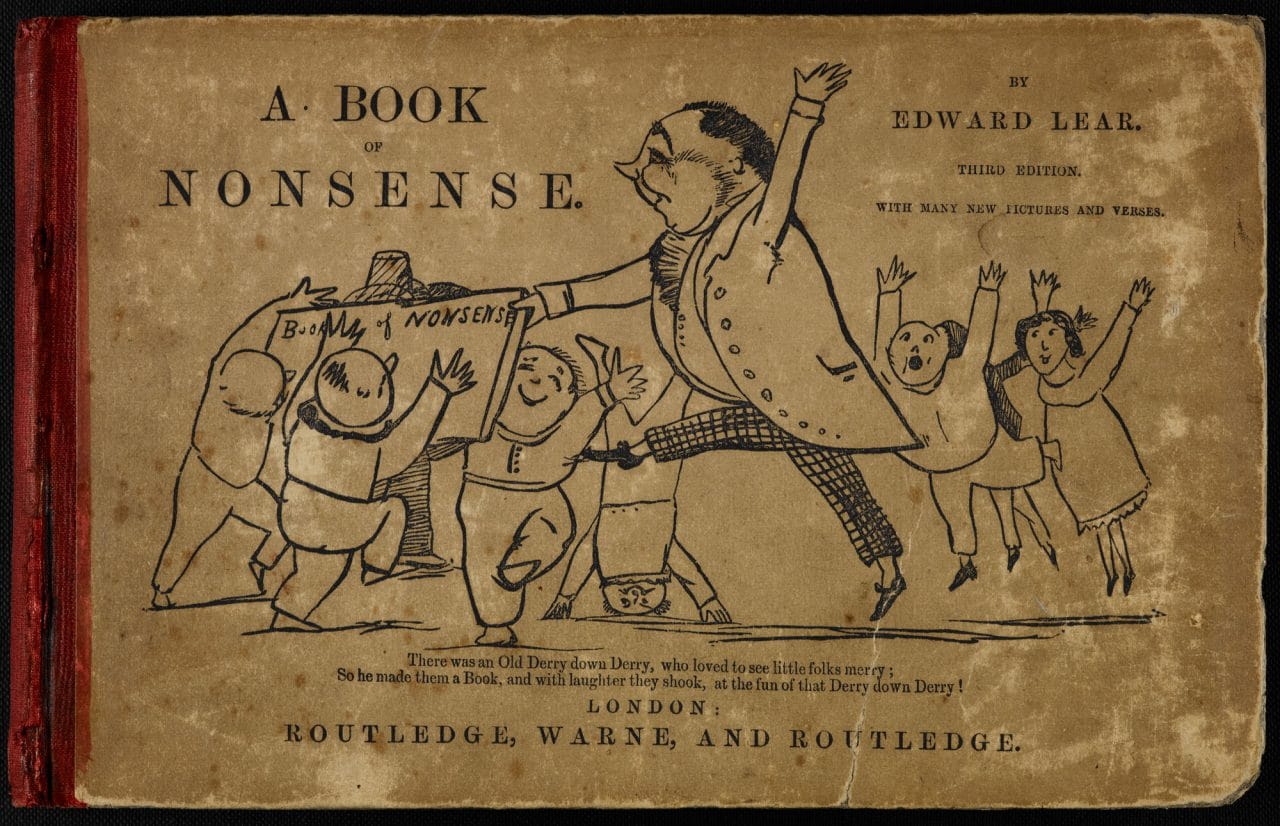

Edward Lear’s A Book of Nonsense

出版日期: 1861 文学时期: Victorian 类型: Children's Literature

Quirky and infectiously absurd, Edward Lear’s ‘nonsense’ writings have been treasured by generations of children, who adore their humour and wild surrealism. His two-volume collection of poems and drawings, A Book of Nonsense (1846), was so successful that it has never been out of print since. But despite the apparent whimsy of poems such as ‘The Owl and the Pussy-cat’, a strong vein of melancholy lies beneath their surface. Some critics have interpreted Lear as a satirist, or even a forerunner of artistic movements such as Dadaism.

Nonsenses and Limericks

Today, the name Edward Lear is closely associated in many minds with a particular form of poetry: the limerick. Surprisingly, Lear himself didn’t use the term, preferring to call the lyrics he wrote ‘Nonsenses’. Nonetheless, the word ‘limerick’ is usually used to describe a verse form five lines long with an ingenious, tightly defined arrangement of rhyme and rhythm, exactly matching that used by Lear:

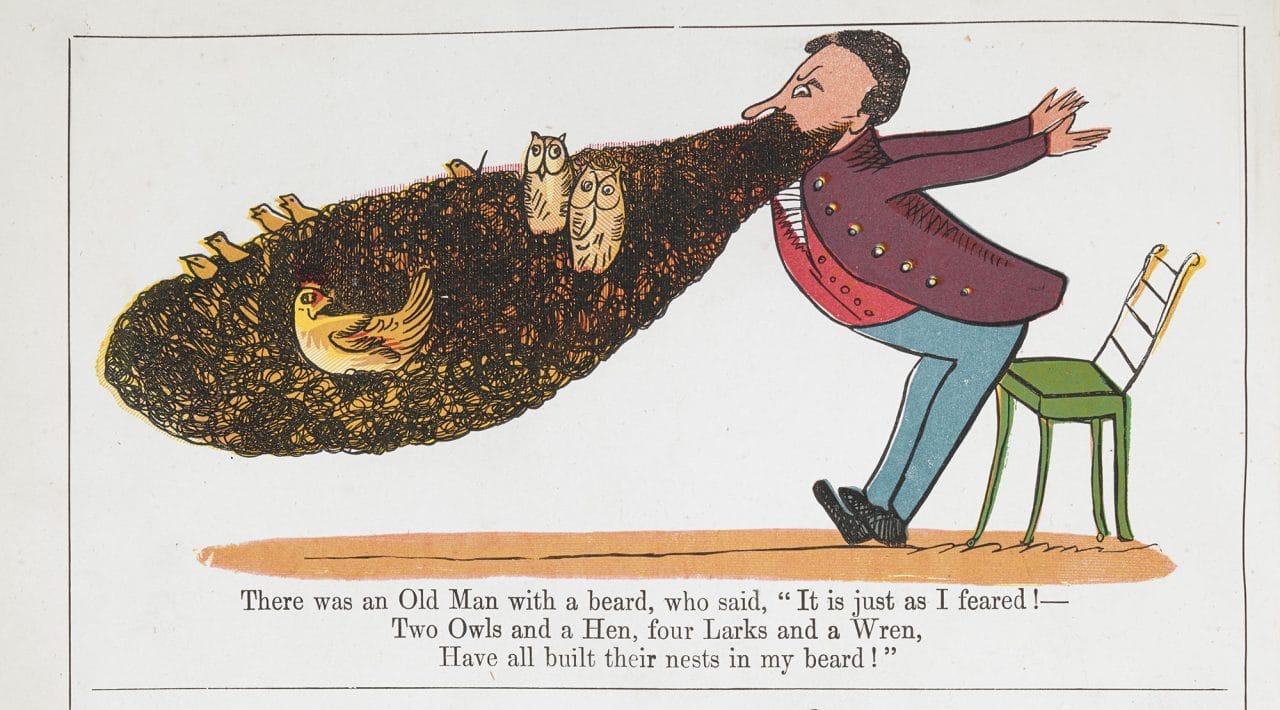

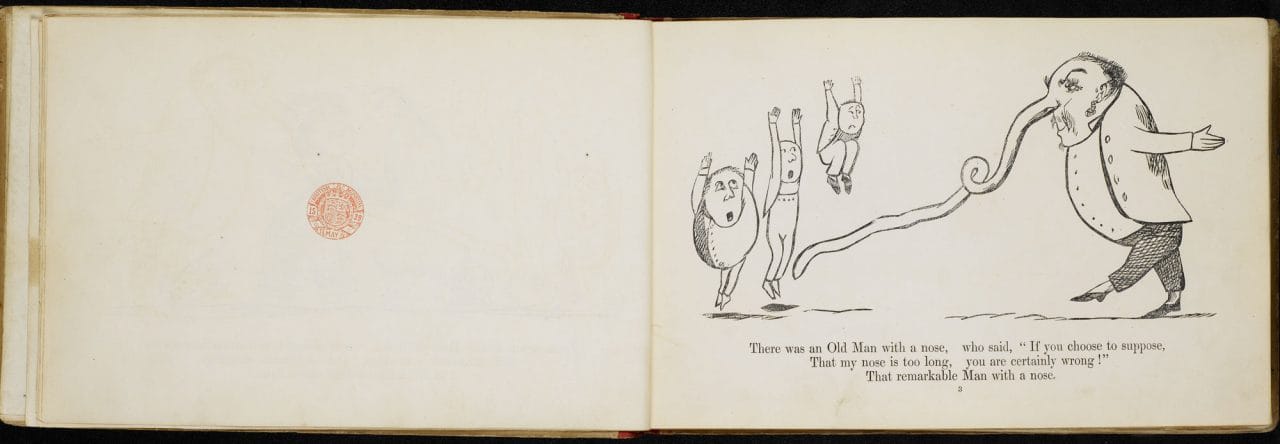

There was an Old Man with a beard,

Who said, ‘It is just as I feared!—

Two Owls and a Hen,

Four Larks and a Wren,

Have all built their nests in my beard!’

‘There was an Old Man with a Beard’ and ‘There was an Old Man with a Nose’ read by Derek Jacobi. Courtesy of Naxos Audiobooks.

In the limerick form, the rhyme scheme runs AABBA, meaning that the first and second lines rhyme with the last (something Lear often emphasises by simply repeating the word at the end of the first line with the word at the end of the last: here ‘beard’). The effect is heightened by the number of syllables in each line, which runs 8/8/5/5/8 – a musical, almost songlike structure that practically demands to be read aloud.

Scholars are unsure when or where the limerick originated, but Lear did more than anyone to popularise the form, penning hundreds of limericks whose irreverent humour has never been rivalled:

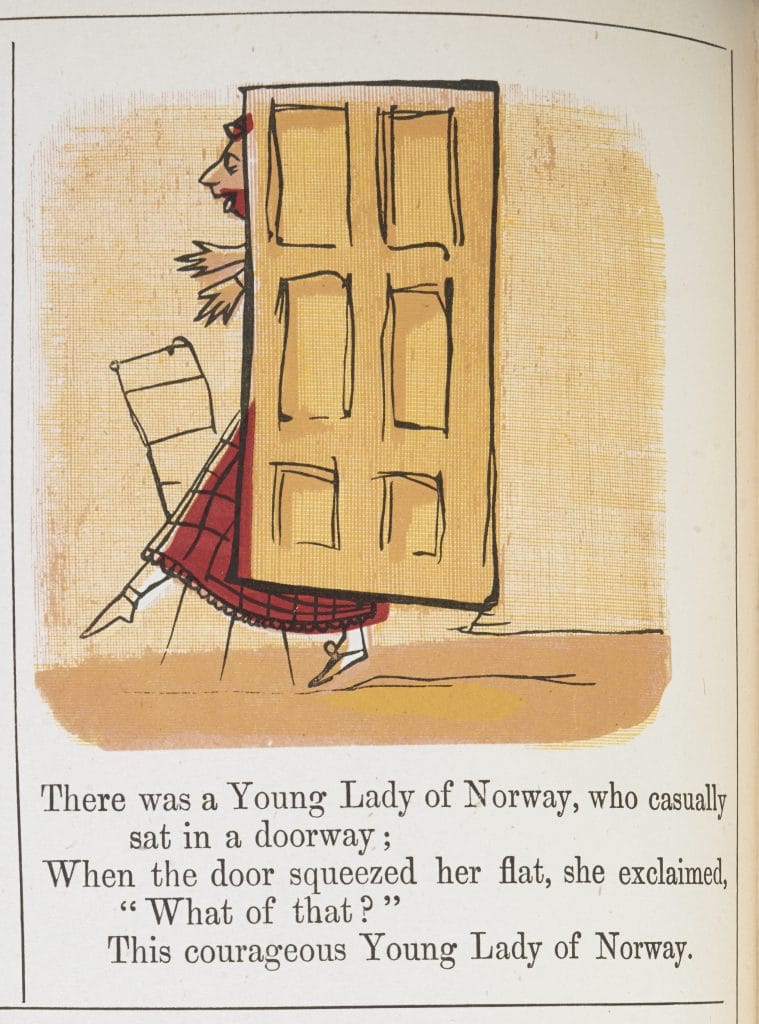

There was a Young Lady of Norway,

Who casually sat in a doorway;

When the door squeezed her flat, she exclaimed ‘What of that?’

This courageous Young Lady of Norway.

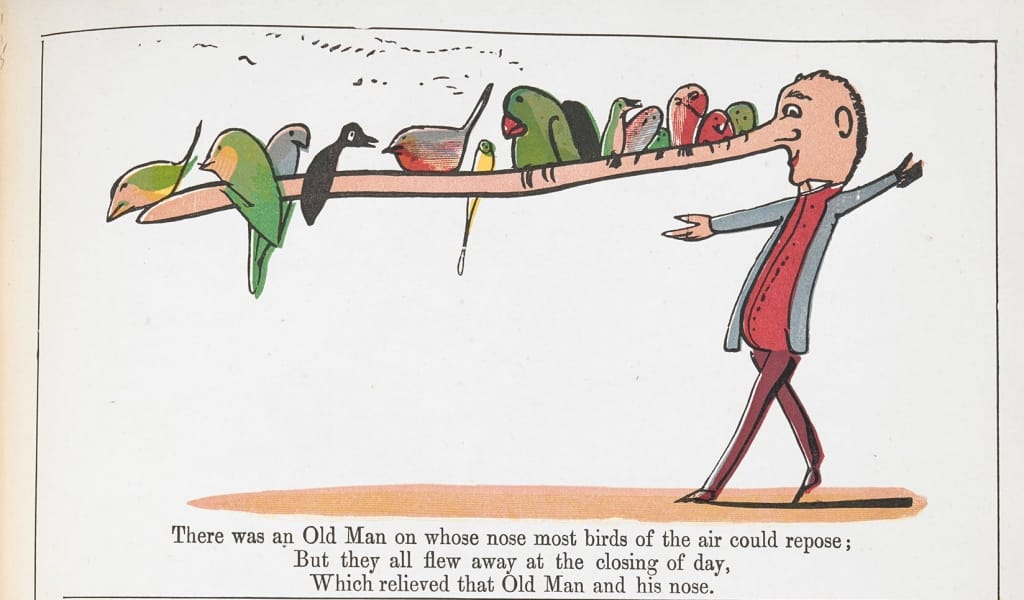

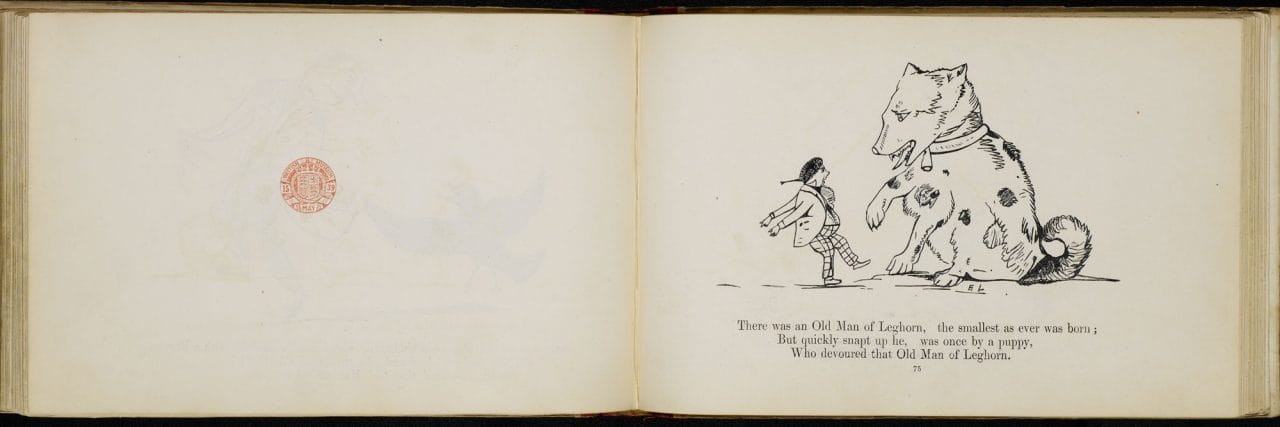

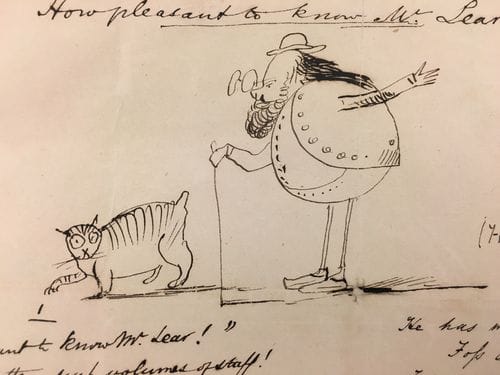

Almost always, Lear’s limericks focus on one person, whose singular attributes (an over-bushy beard, a too-long chin) put them into conflict with the outside world. And though the effects are funny, it’s worth noting that these are often tales of survival against the odds: the eccentric oddball who triumphs against dull conformity is a repeated theme. It is not hard to see them as Lear’s image of his own life.

Since Lear’s death, limericks have become ubiquitous in English-speaking culture, promoted by comic writers such as the American Ogden Nash (1902–1971) and the Irish-British Spike Milligan (1918–2002). Although many modern limericks are much less innocent than those penned by Lear – many have a strong vein of sexual humour – they retain a surreal edge that he would no doubt admire. Verbally ingenious and gloriously eccentric, they are somehow quintessentially British.

Edward Lear’s life

Born 20th of no fewer than 21 children, Edward Lear grew up in a noisy middle-class household in Holloway, north London. His father was a stockbroker, but seems to have had money troubles, and his sister Ann, 21 years older, oversaw his upbringing. The young Edward was educated mostly at home, largely because he suffered from epilepsy and chronic asthma, but displayed talents as an artist and draughtsman, providing illustrations for the ornithologist Prideaux Selby. In his early 20s he developed a reputation as a brilliant observer of animals, but his poor eyesight made the work challenging, and he soon began to concentrate on painting landscape watercolours, equally vivid but much freer.

Lear found the damp British climate a challenge, and he moved to Rome in 1837, joining a circle of expatriate English painters and writers. His time there led to two richly illustrated books, Views in Rome and its Environs (1841) and Illustrated Excursions in Italy (1846–47). The second was so well regarded that one of its readers, Queen Victoria, requested Lear give her drawing lessons.

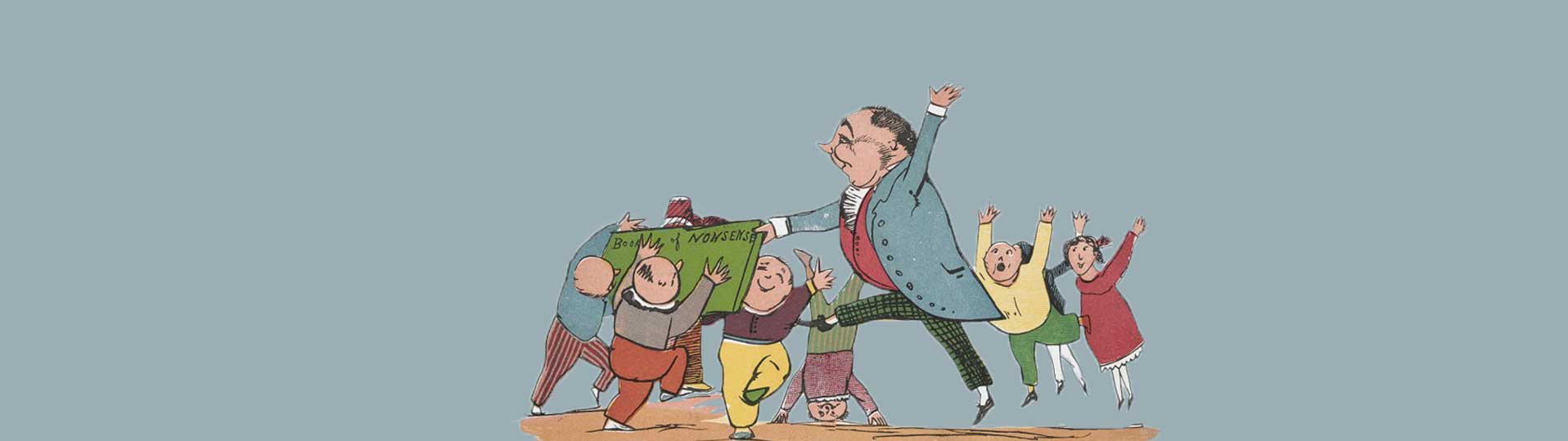

A Book of Nonsense

Lear later described how he had once stayed in a country house ‘where children and mirth abounded’ – an experience that inspired him to compose most of what became A Book of Nonsense. Published in two volumes in February 1846, the book was aimed at children and contained no fewer than 72 limericks. Almost all are funny, and many are deliciously absurd:

There was a Young Lady whose chin,

Resembled the point of a pin;

So she had it made sharp,

And purchased a harp,

And played several tunes with her chin.

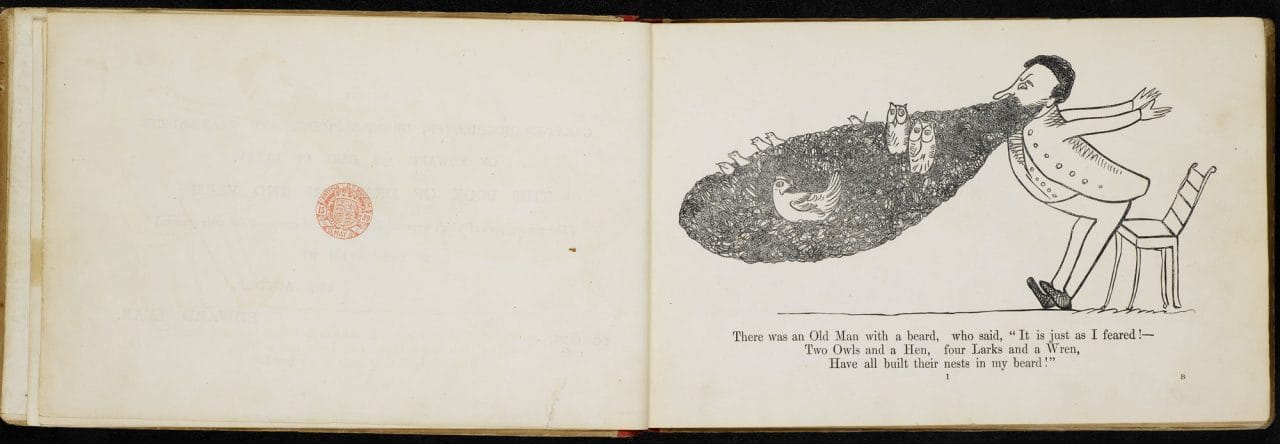

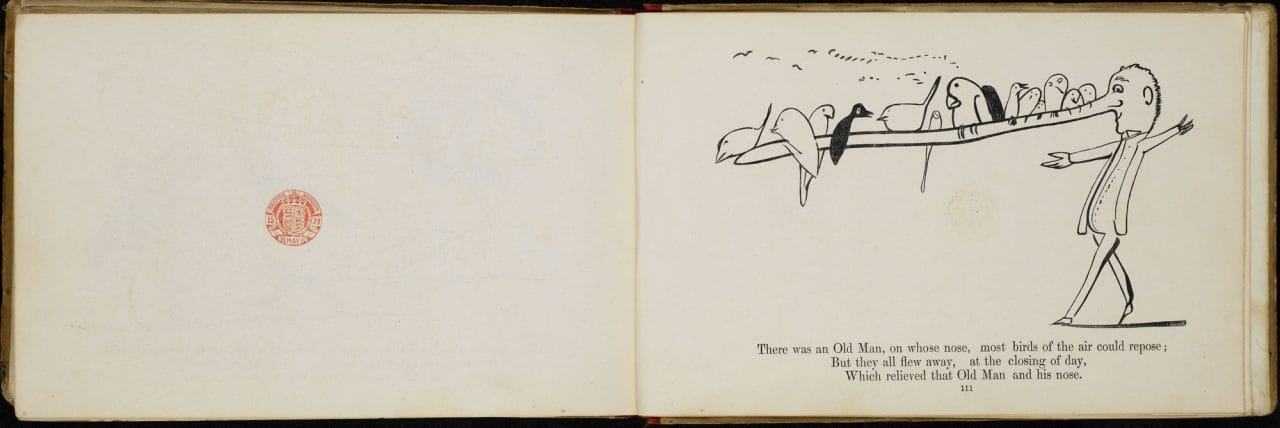

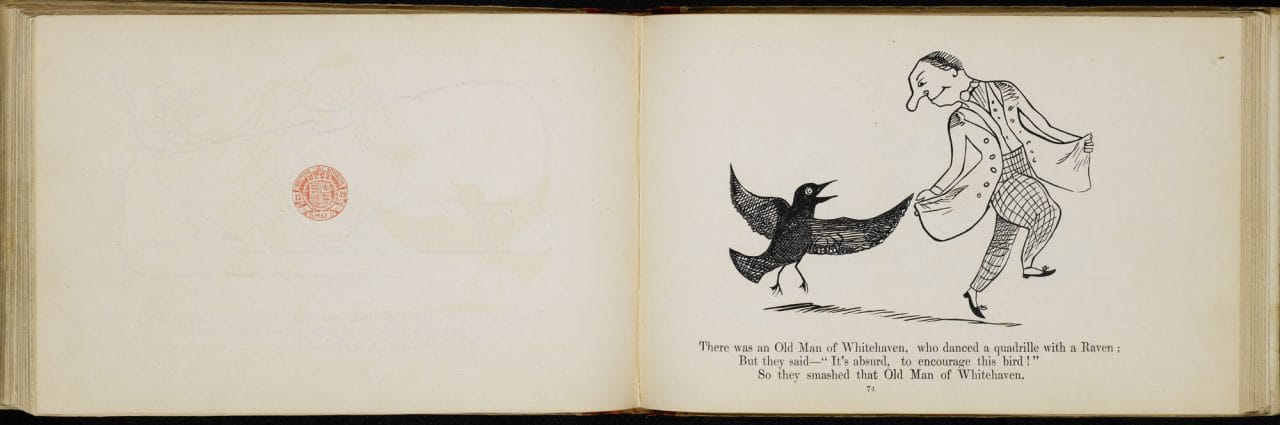

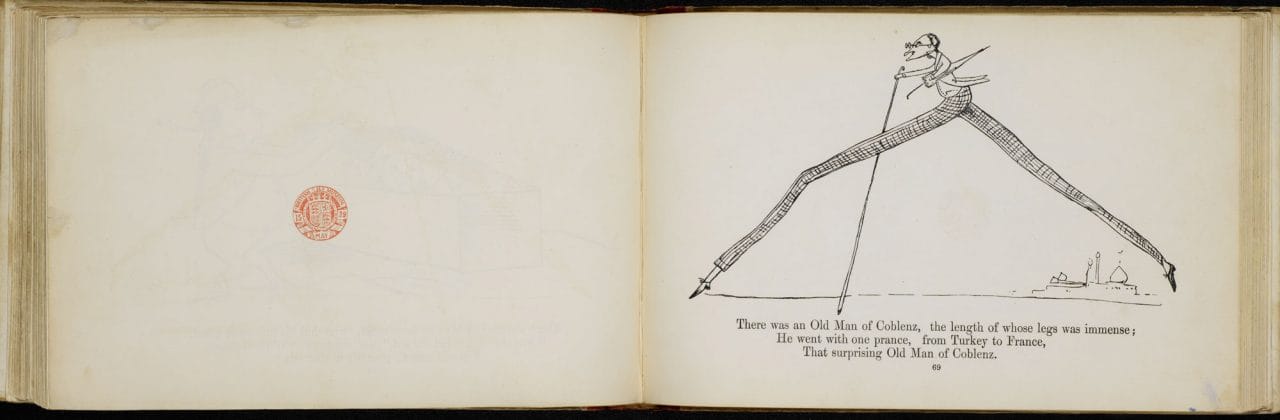

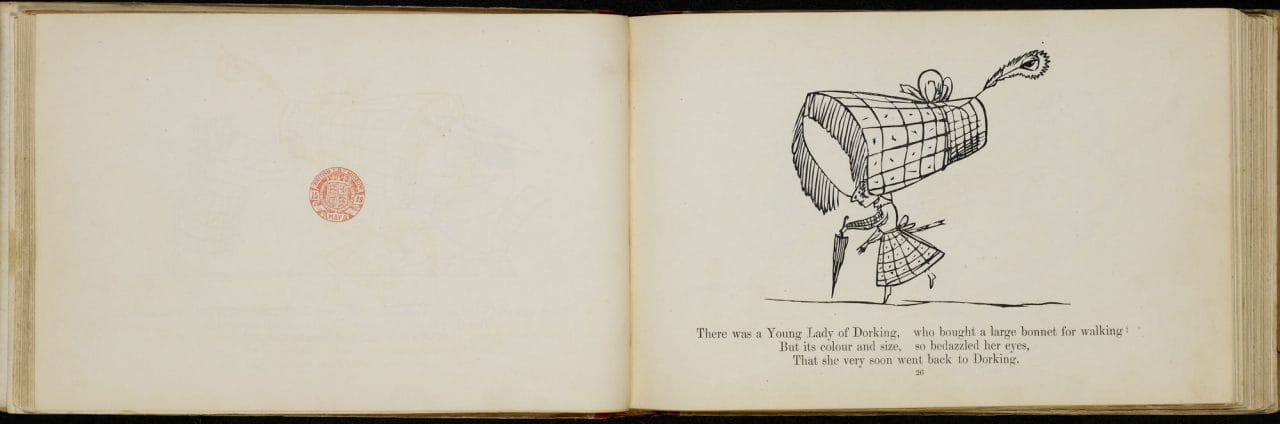

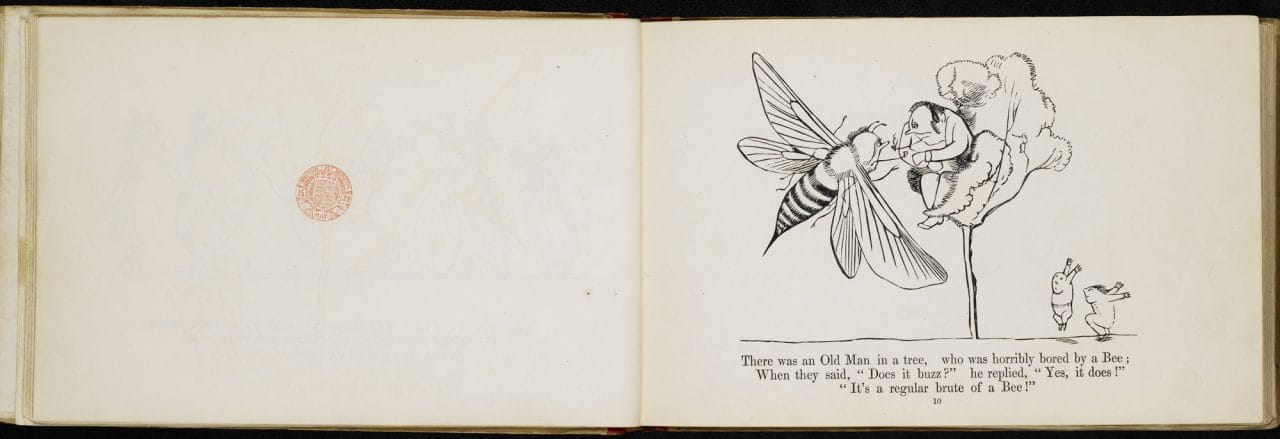

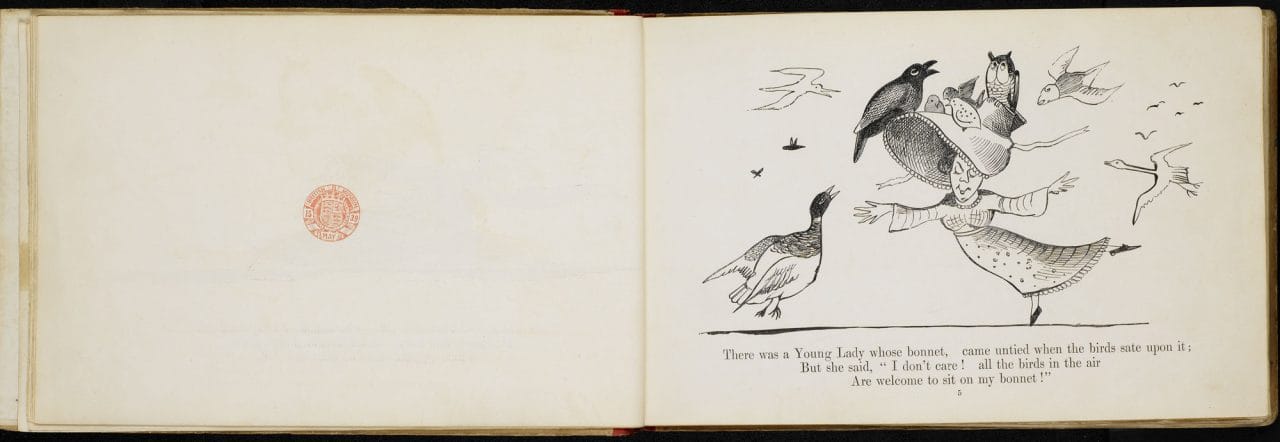

Lear follows this surreal miniature with a description of an ‘Old Man of Kilkenny’ who spends his fortune on ‘onions and honey’, then a poem about an ‘Old Person of Ischia, / Whose conduct grew friskier and friskier’. Yet perhaps what makes the Book of Nonsense so appealing are the illustrations that accompany each short parcel of verse, done by Lear in straightforward but characterful pen and ink, each picture a window into a joyously freakish world.

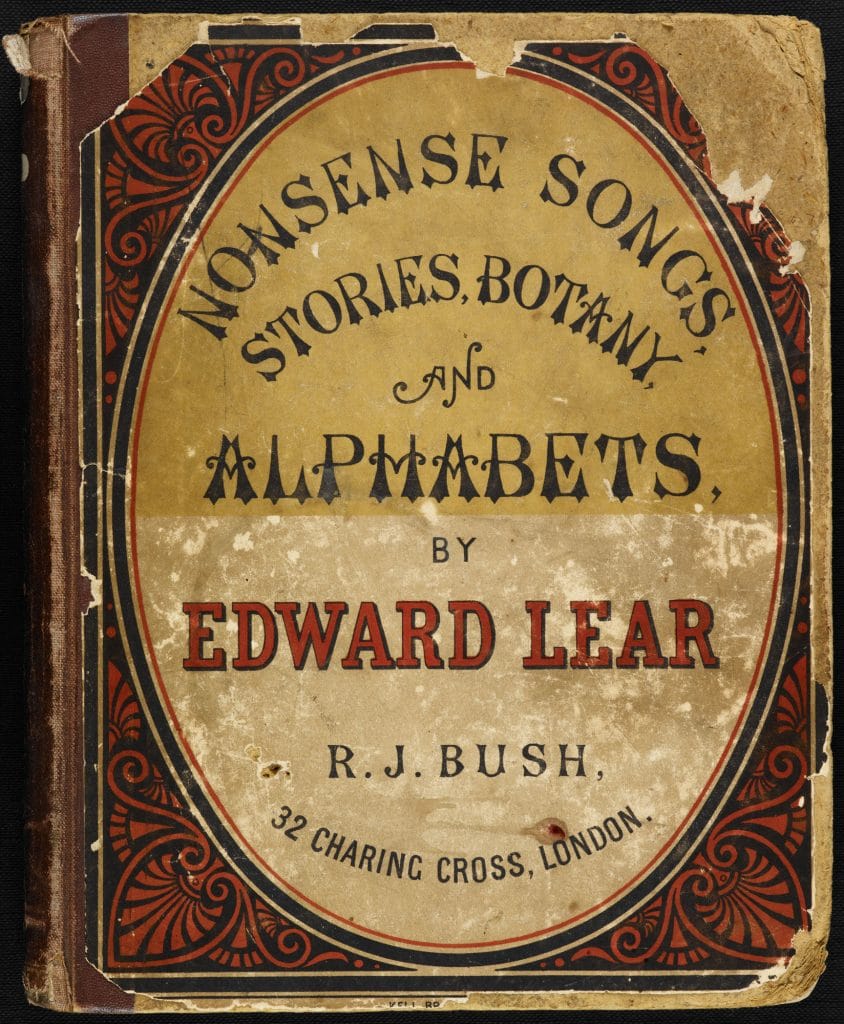

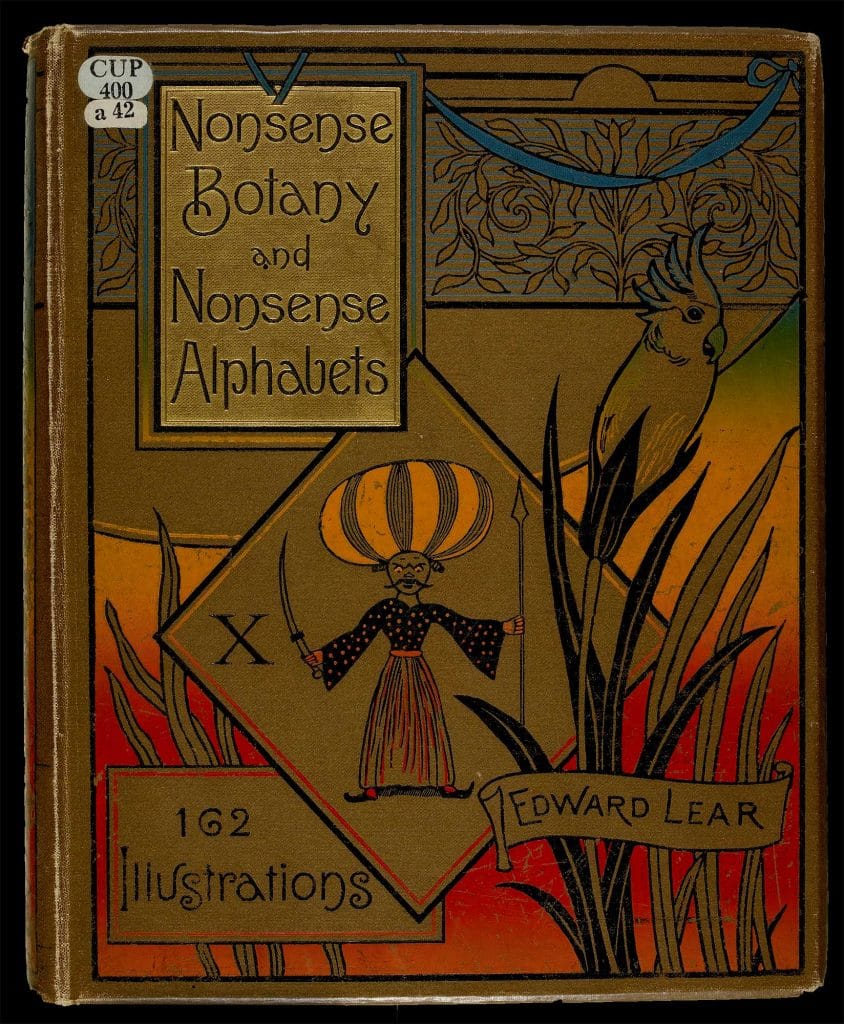

Despite being largely ignored when it first came out, the fame of A Book of Nonsense steadily grew, and by the time the third, single-volume edition appeared in 1861, Lear was a household name in Britain. Although somewhat perplexed by this success, he capitalised upon it with Nonsense Songs, Stories, Botany and Alphabets (1871) – a collection of more complex poems that contains the famously romantic tale of ‘The Owl and the Pussy-cat’ – and More Nonsense (1872). His last ‘nonsense’ book, Laughable Lyrics, appeared in 1877. It is populated by a menagerie of strange and fantastical animals, among them a pair of ‘Discobboloses’, who listen to the cry of the ‘Biscuit Buffalo’, and the ‘Quangle Wangle’, who lives on top of the mysteriously named ‘Crumpetty Tree’ wearing a beaver hat 102 feet wide.

Lovelorn lyrics

Biographers have speculated that Lear might not have turned to children’s literature if his career as a self-proclaimed ‘dirty landscape painter’ had been more successful. Despite extensive travels across Europe and further beyond – through Italy, Greece, Albania, Palestine, Syria and India – and a remarkable work rate that produced an estimated 10,000 watercolours, he was never fashionable among art collectors, and often struggled financially. Lear’s personal life was bleak, too: desperately wanting to have children, he considered proposing to a woman called Gussie Bethell, but decided against it, perhaps fearing that his epilepsy would be passed on. More private emotions may have come into it, too; Lear had a series of intense friendships with men, most of all the young barrister Franklin Lushington, although his feelings were never reciprocated. After Lear’s death, Lushington destroyed most of Lear’s papers.

In this light, Lear’s verse takes on a somewhat darker hue, particularly his later poems. Lost love is an insistent theme: one of his saddest works is ‘The Pelican Chorus’, printed in Laughable Lyrics, which tells of a pair of pelicans who lose their beloved daughter to a crane:

Often since, in the nights of June,

We sit on the sand and watch the moon;—

She has gone to the great Gromboolian plain,

And we probably never shall meet again!

Similar feelings course through ‘The Courtship of the Yonghy-Bongy-Bò’, the story of an eccentric, large-headed man tired of ‘living singly’ who tries – and fails – to convince a woman to be his wife.

Lear himself never appears to have had a successful romantic or sexual relationship, and his beloved servant Giorgio Kokali died in 1883, leaving him alone apart from his cat Foss, immortalised in many drawings. His final years in Italy were solitary, although an 1886 article in The Pall-Mall Gazette by the influential artist and critic John Ruskin, declaring that Lear was ‘first of my hundred authors’, gave him a great deal of comfort.

Written by: Andrew Dickson

This article is available under the (Creative Commons License).