Emily Brontë ‘s Wuthering Heights

出版日期: 1847 文学时期: Victorian 类型: Victorian literature

Published in 1847, Wuthering Heights is Emily Brontë’s (1818-1848) only novel. Blending realism, romance and the Gothic, some early reviewers thought it immoral and abhorrent; others praised its originality and ‘rugged power’. The house at the Heights is situated in bleak moorland, and the wild setting is a powerful presence as the story unfolds. The text has multiple narrative viewpoints. The main perspectives come from Lockwood, a southerner who finds Yorkshire an alien place; and a servant, Nelly Dean, who moves between the Heights and Brontë’s contrasting location of Thrushcross Grange.

Who is Heathcliff?

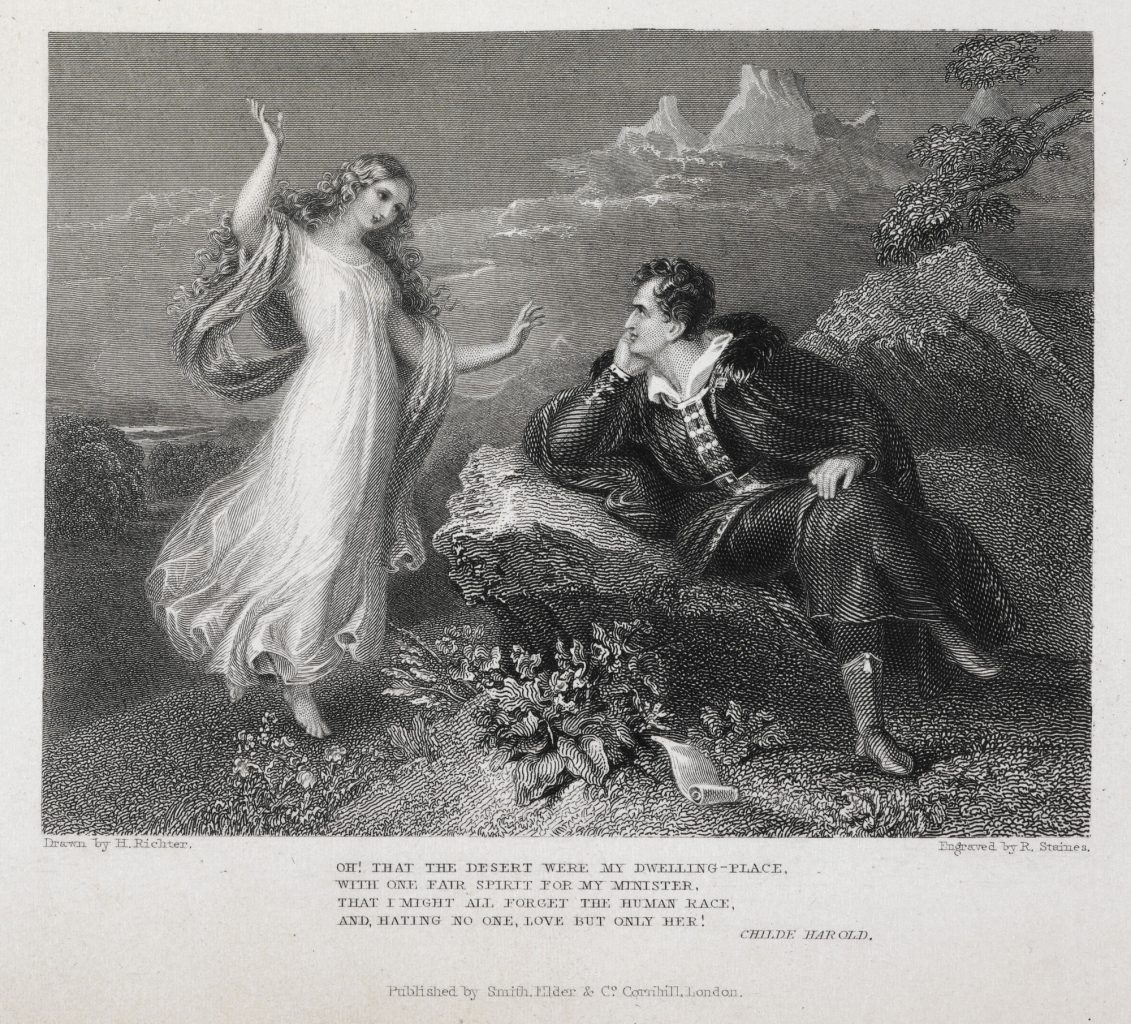

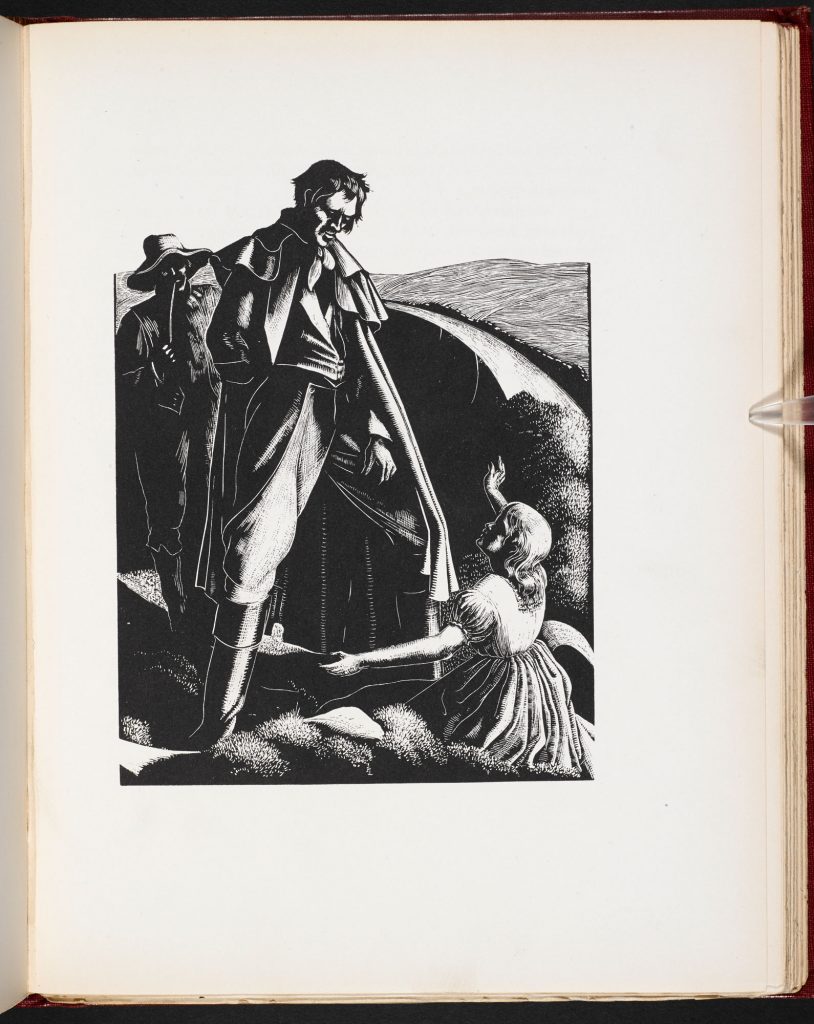

Heathcliff is a dark, enigmatic and brooding. He is sometimes called a ‘Byronic hero’, but he is much more complex and ambivalent character than this.

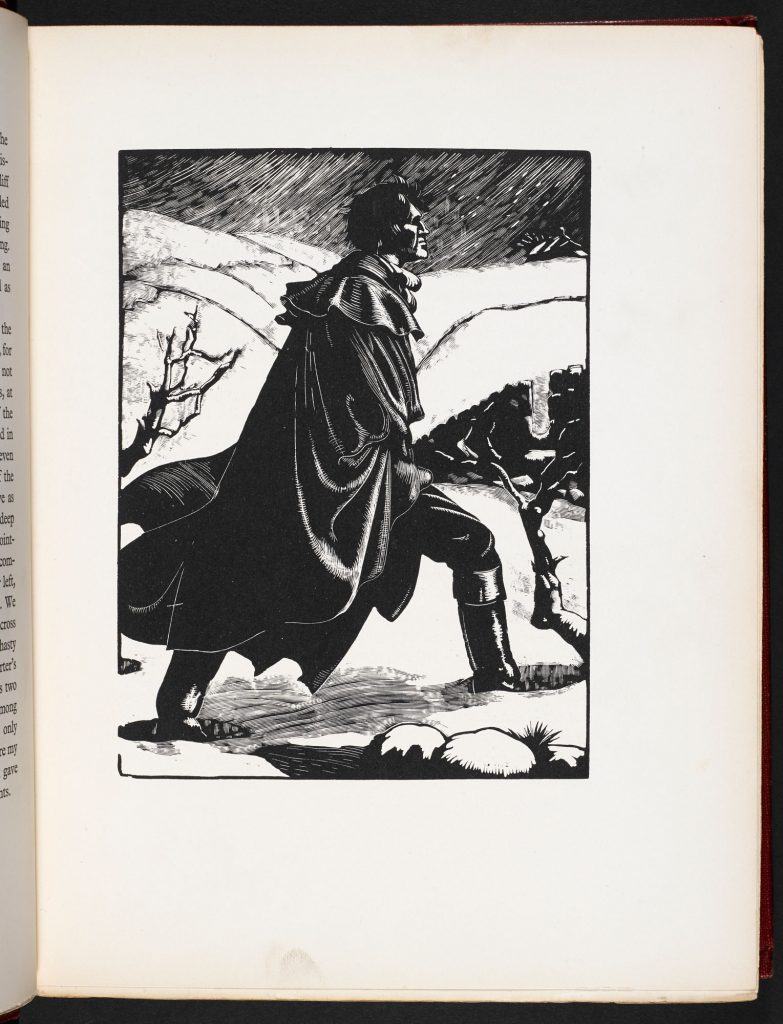

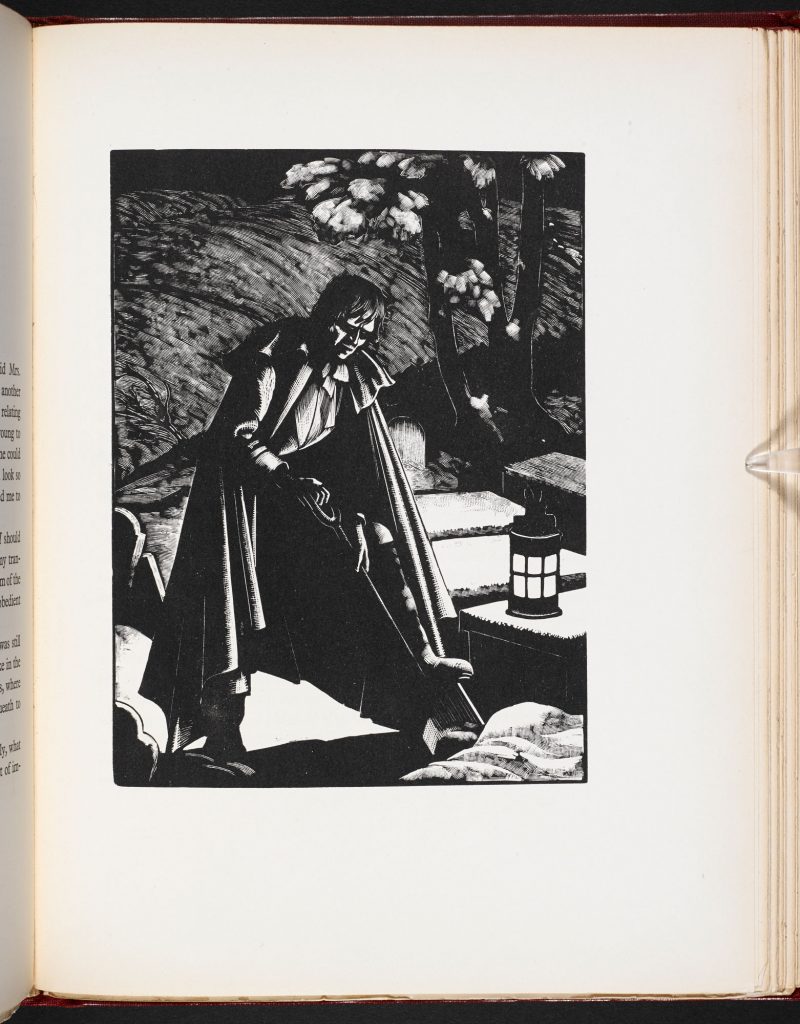

The passionate intensities of Wuthering Heights create a world of revenge without law or justice, in which Heathcliff is the dominant, overbearing presence, both outsider and insider, starving orphan and cruel landlord. Like the book itself, he is both remarkably self-disciplined and completely wild.

In 1850, after her sister’s death, Charlotte Brontë wrote a preface to the novel in which she wrongly describes Heathcliff as ‘unredeemed; never once swerving in his arrow-straight course to perdition’, someone who only once shows human feeling, in his treatment of Hareton Earnshaw. His love for Catherine, writes Charlotte, is ‘a sentiment fierce and inhuman: a passion such as might boil and glow in the bad essence of some evil genius; a fire that might form the tormented centre–the ever-suffering soul of a magnate of the infernal world.’ This misrecognises the dramatic complexity of the novel, which never encourages its readers to fall into such simple moral or religious judgements.

Like a great novelist, Heathcliff is a brilliant constructor of plots involving other people, which bring them (and us) into the presence of the most raw and deep emotions.

Heathcliff’s origins

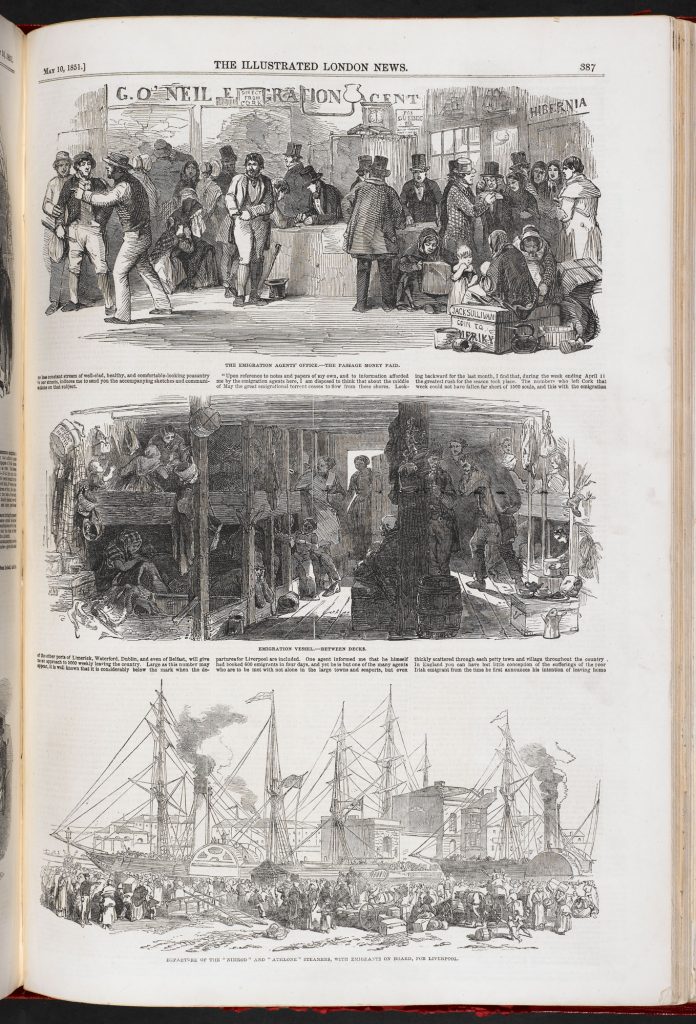

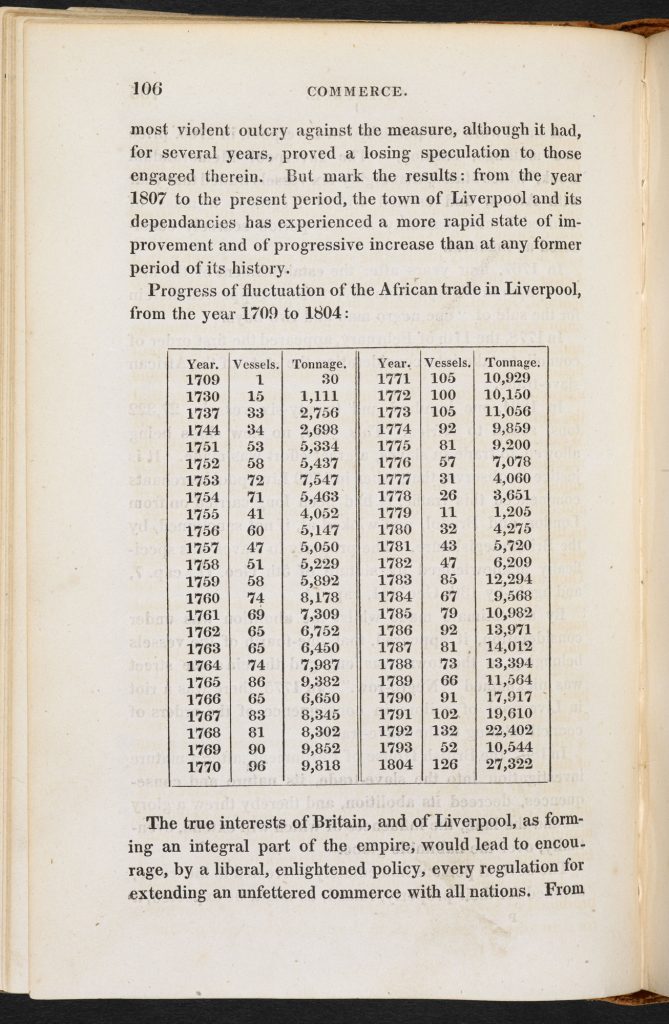

Heathcliff‘s origins are deeply mysterious: we know that he is picked up on the streets of Liverpool by Mr Earnshaw but little else for certain. Liverpool was both a major port for Ireland (where the Brontë family originated and which suffered a terrible famine in the 1840s, the decade the novel was published) and of the slave trade. But the way that Emily chose to write the novel with interlocking and inset narrators means that we can never be certain about Heathcliff, nor is it ever clear what our feelings should be. Our response to Heathcliff, like that of the characters of the novel, is constantly in motion.

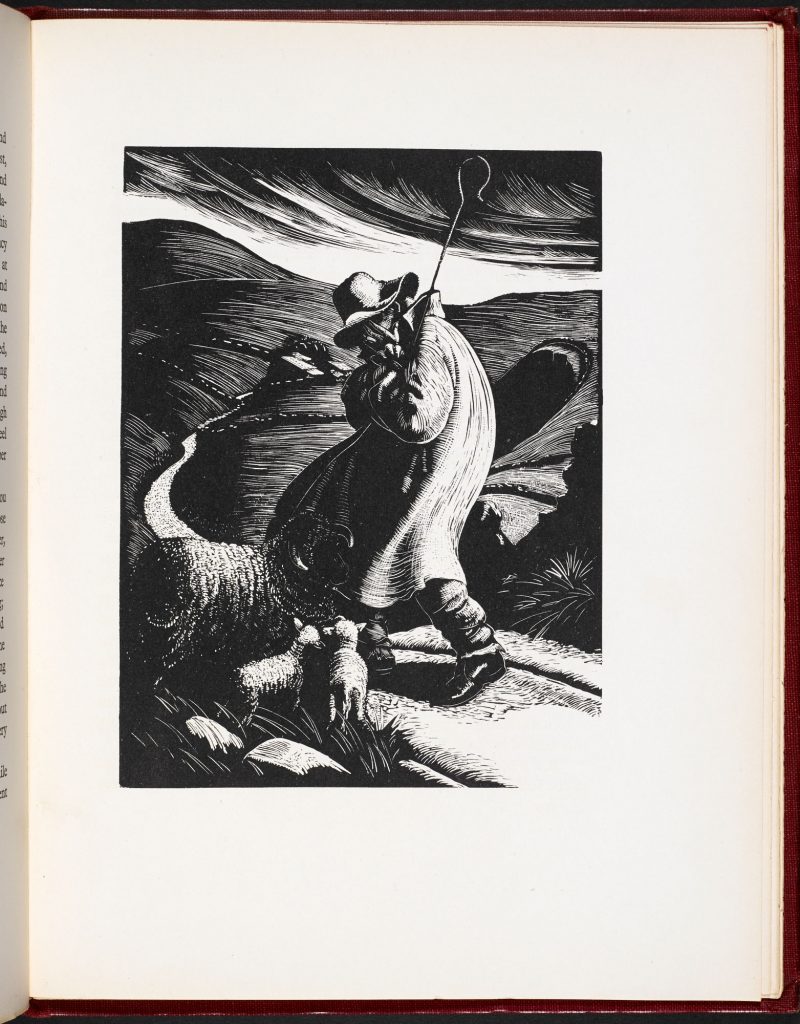

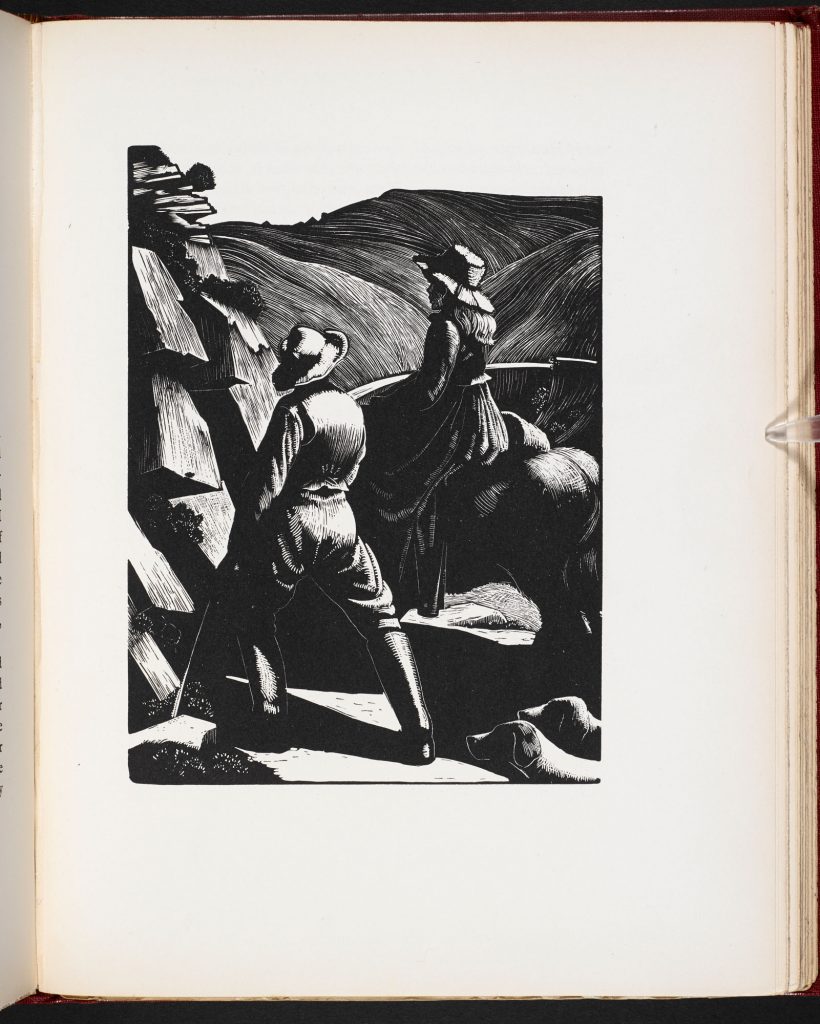

The landscape of Wuthering Heights

Emily Brontë lived not in a mythical moorland fastness but in a rapidly industrialising world. Her home, Haworth Parsonage, looked down on a small Yorkshire mill town and backed onto the moors. The bleakly beautiful West Yorkshire moors have often helped to define in important ways how readers and critics have interpreted Wuthering Heights – as a strange and wild book about a remote and unfamiliar landscape. Yet it is important to remember that Haworth was a modern working town, with several mills and a good deal of industrial unrest. Although it might have seemed distant from London, it was not so far from Manchester (the ‘shock city of the age’) and the bustling metropolis of Leeds. It was part of a world in rapid motion that witnessed the dramatic mid-Victorian transformation of nature and work in both town and country, changes powered by the railways (for which Branwell Brontë worked) and by the mills that surrounded them.

But this was not simply a change of landscape. As Terry Eagleton writes:

It was not just a question of cotton mills, rural enclosures, hunger and class-struggle, but of the crystallising of a whole new sensibility, one appropriate to an England which was becoming for the first time a largely urban society. It was a matter of learning new disciplines and habits of feeling, new rhythms of time and organisation of space, new forms of repression, deference and self-fashioning. A whole new mode of human subjectivity was in the making … both aspiring and frustrated, rootless and solitary yet resourceful and self-reliant. [1]

This new world, and the landscapes and townscapes it brought with it were decisive presences in Emily and her sisters’ lives and writing.

A world of passionate intensities

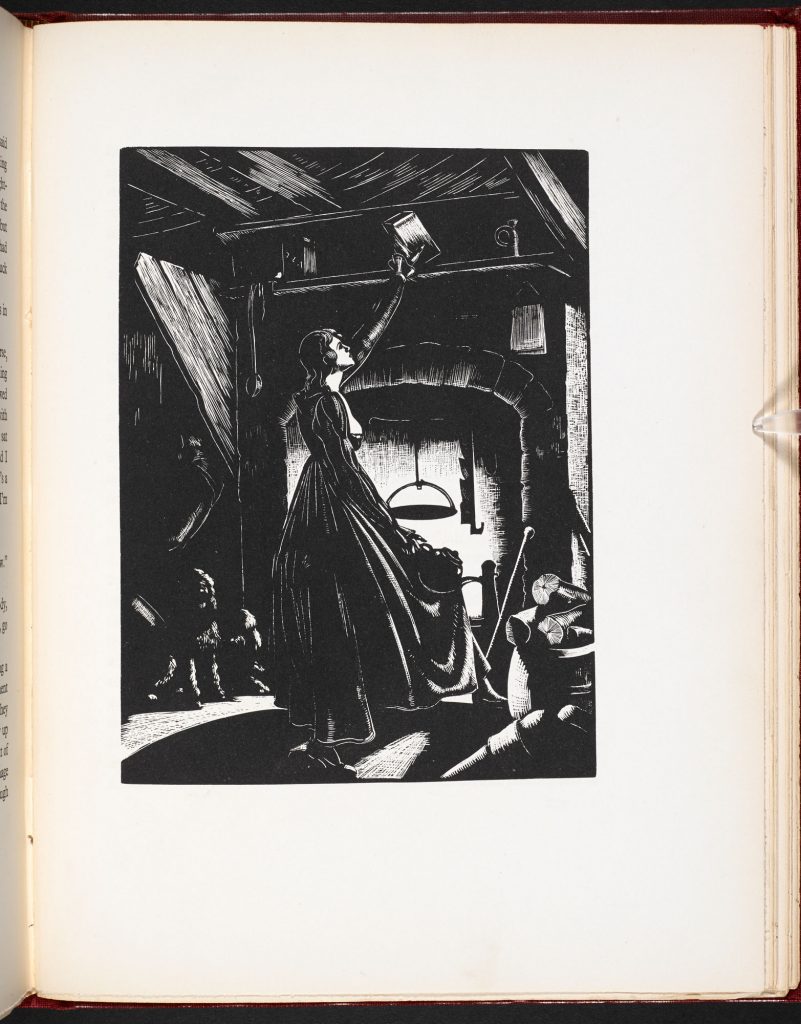

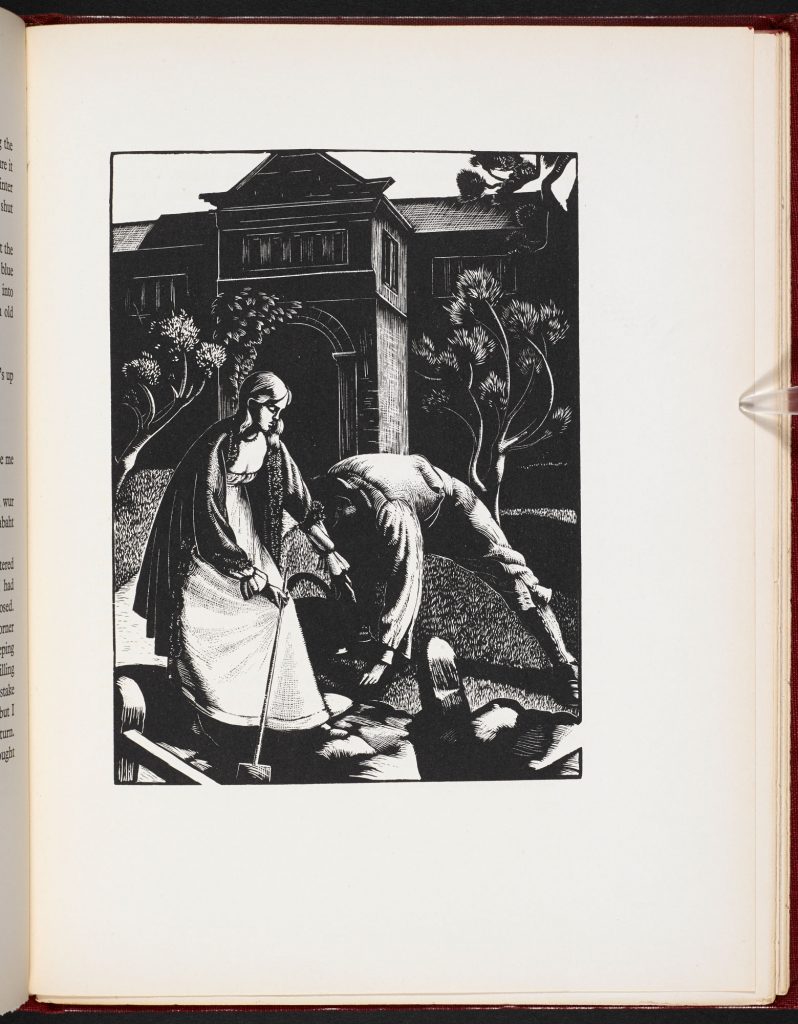

Wuthering Heights creates a world of passionate intensities, in which particular events are burned on the characters’ and readers’ memories, beyond reason, measure or reserve. Terror stalks the book and defines so many of its central relationships, concerned as it is with the ecstatic, eerie and mad. The book plays with death, courts death, stages death, even jokes with death, as we see when the dying Catherine is haunted by the face in the ‘black press’ (ch. 12) or when Heathcliff breaks through the side of Catherine’s coffin or hangs his wife Isabella’s dog from a hook in the garden. The book is fascinated by what lies at the limits of the human and is haunted by the forces of death and the diabolical, by compulsive modes of behaviour, by infantile and sublimely powerful emotions, by the force of irresistible will, and by the terrible consequences done to human beings by radical evil. The book is full of animals, spirits and ghosts, and those, like Heathcliff, about whom we can never be sure.

The extraordinary within the real

Wuthering Heights is also a highly organised and rationally planned novel, with a complex time scheme and several interlocking narrators. It sets its extraordinary actions in a vividly realised family history and landscape. It is fascinated by the power of fantasy, particularly erotic fantasy, in people’s lives – Isabella thinks of Heathcliff as ‘“a hero of romance”’ (ch. 14) until she learns the truth of his brutality – but those fantasies take their place within a carefully plotted story about inheritance, intermarriage and theft. The erotic is not separated from the economic, or from the passage of power and land across generations. Emily Brontë was fascinated by extreme emotions, radically opposing mental and social forces, and the creation of moments of moral revelation and transformation that were typical both of Gothic fiction and Victorian melodrama, but she could control, ironize and discipline those energies to serious purpose. Through the care she took to implant her writing in a particular history, landscape and material world, through complex time-schemes and inset narrators, through making Gothic into a mode of psychic exploration, she decisively extended the range and affective power of the English novel.

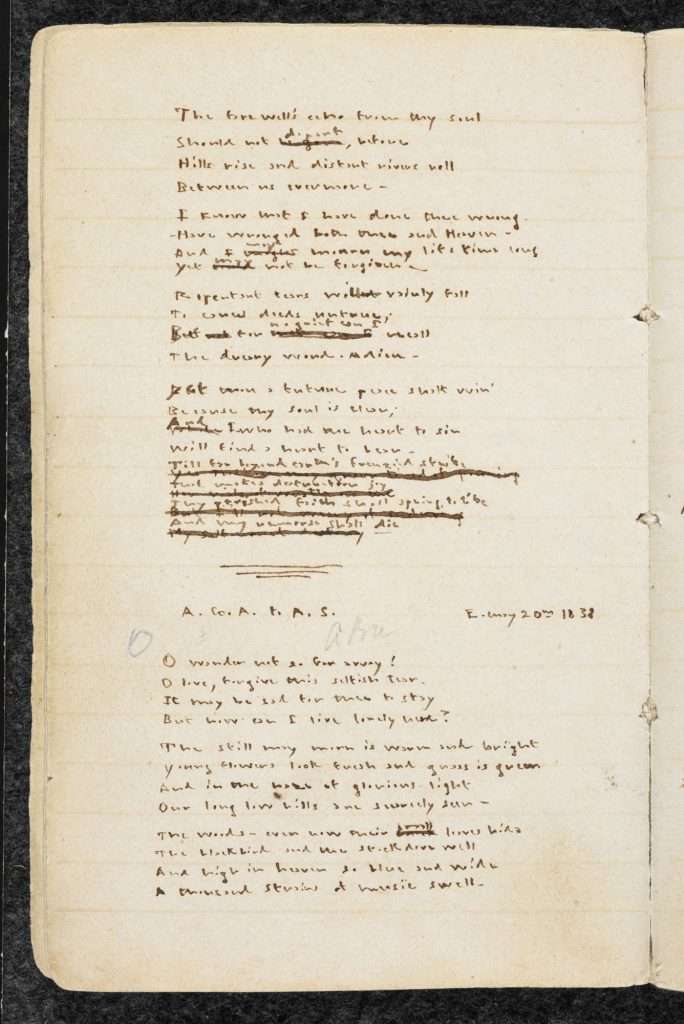

Poetry

Emily Bronte is one of the very few authors to be an important poet as well as a major novelist, and there is a close relationship between the two bodies of work. Many of her poems appeared first in stories of the ‘Gondal’ world that she created with her sister Anne; she collected them in a manuscript notebook (now in the British Library) entitled ‘Gondal Poems’ although when she published six of them in the collection Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell (1846), she removed all references to Gondal. So the poems do not depend on an underlying narrative context for their power; like other great Victorian poems, they dramatize questions of identity and self through different personae in impassioned utterance and often extreme situations. Like Wuthering Heights, they are drawn to emotional extremity and passion, to scenes of loss and oblivion, and to the affirmation of desire in the face of death.

Contributor:John Bowen

John Bowen is a Professor of 19th century literature at the University of York. His main research area is 19th-century fiction, in particular the work of Charles Dickens, but he has also written on modern poetry and fiction, as well as essays on literary theory.

The text in this article is available under the terms of a Creative Commons License.