Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

出版日期: 1925 文学时期: Romantic 类型: Gothic

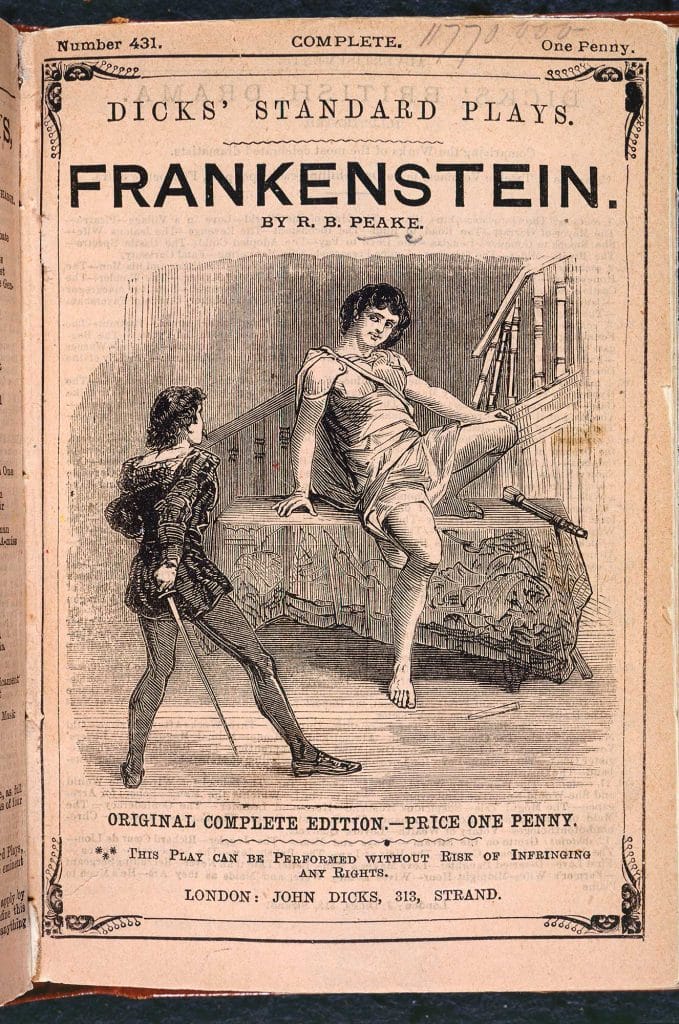

The story of how Frankenstein came into being is almost as remarkable as the book. Staying at a villa in Geneva, Switzerland in the summer of 1816 were a ragtag group of English writers and intellectuals: Lord Byron, his pregnant former lover Clair Clairmont, his physician John Polidori, along with Mary Godwin and Percy Shelley (the two were not married until later in the year). Forced to stay indoors by stormy weather, the party whiled away the evening hours telling ghost stories – one of which became Frankenstein, Or the Modern Prometheus. The story of a scientist who creates a monstrous being from an assemblage of body parts (‘Frankenstein’ is the scientist’s name, not – as is often supposed – the monster’s), Shelley’s ‘waking dream’ asks deep questions about the nature of consciousness and the role of science in modern life. It has also inspired an apparently endless series of horror movies and dramatisations – all the more remarkable for being written by a woman of just 18.

Who was Mary Shelley?

Born in London in 1797, Mary Godwin was named for her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft – a sad memorial, given that her mother died just 11 days after her birth. The young Mary grew up in a household that can only be described as unconventional: her father William was an anarchist philosopher who had an illegitimate daughter from another marriage, and when he remarried in 1801 another two children joined the household. The family were often poor, but their circle of friends included such figures as the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge and the writers Charles and Mary Lamb. Godwin himself taught Mary at home, ensuring that her education was top-notch – highly unusual for a woman at this time.

Always independent minded (her father once described her as ‘singularly bold, somewhat imperious, and active of mind’), Mary met Percy Bysshe Shelley in November 1812 at the age of 15, and, despite the fact that Shelley was already married, the two fell in love. They eloped to mainland Europe in 1813 with almost no money, and embarked on a life together that was ‘very political as well as poetical’, as Mary later described it. She later turned her diary from this period into History of a Six Weeks’ Tour of France, Switzerland and Germany (1817), and kept journals until almost the end of her life. After returning briefly to England, where Mary gave birth to a daughter who died in infancy and then a son, William, who survived, the pair went travelling again in May 1816, arriving in Geneva.

Writer and historian Matthew Sweet un-stitches the literary origins of Frankenstein.

Commissioned by Sky, this is the first of three films to illustrate the literary inspirations behind Penny Dreadful, a major drama series created by John Logan starring Josh Hartnett, Timothy Dalton, Eva Green and Billie Piper.

The birth of Frankenstein

Owing to the lingering effects of a huge volcanic eruption in Indonesia, 1816 became known as ‘the year without a summer’, and the party at the Villa Diodati in Geneva were often stuck indoors, forced to light candles because of the gloom and stormy weather outside. It was during one of these freakishly long summer evenings that Byron suggested they have a competition to tell ghost stories. Neither he nor Percy produced much of substance, but drawing on ancient legends about the undead John Polidori wrote a tale that he later published as The Vampyre, which partly inspired Bram Stoker’s much more famous Victorian novel Dracula (1897). For her part, Mary came up with an eerier and much more imaginative premise: what if a scientist were to assemble a human life form from lifeless body parts? As she later described it:

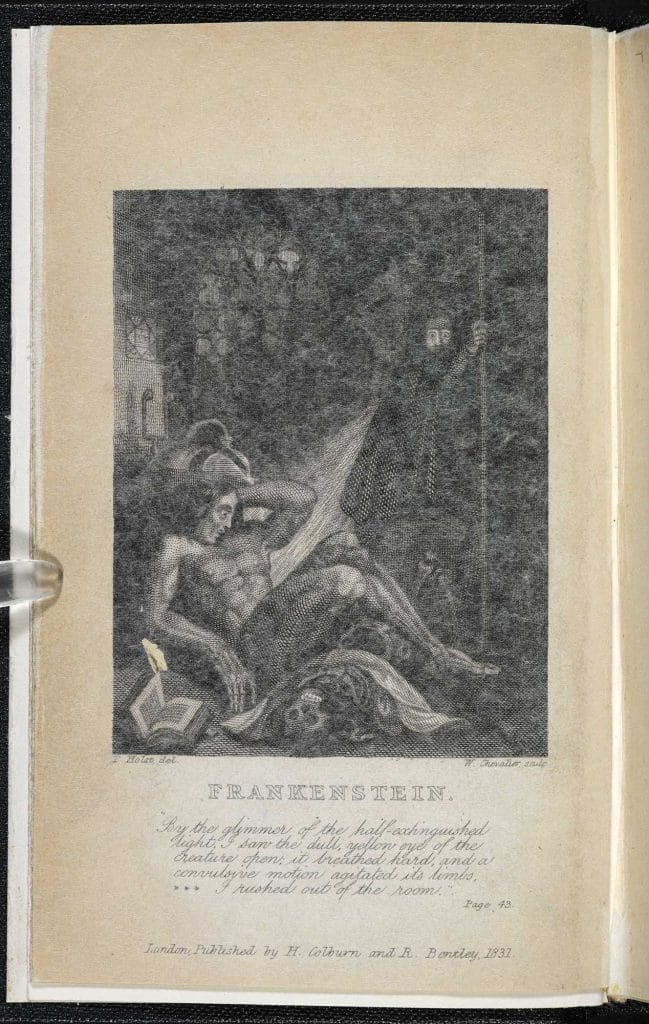

I saw – with shut eyes, but acute mental vision – I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir…

From this dramatic rough sketch, Mary created a short but powerful tale, subtly crafted but also thrillingly readable. It begins in the snowy wastes of the Arctic, where a sea captain encounters Doctor Frankenstein, who tells him of his shocking experiment to create life, and how the Creature he made murdered a young boy – only for the monster to reveal that he did so because he was crazed with loneliness and sorrow.

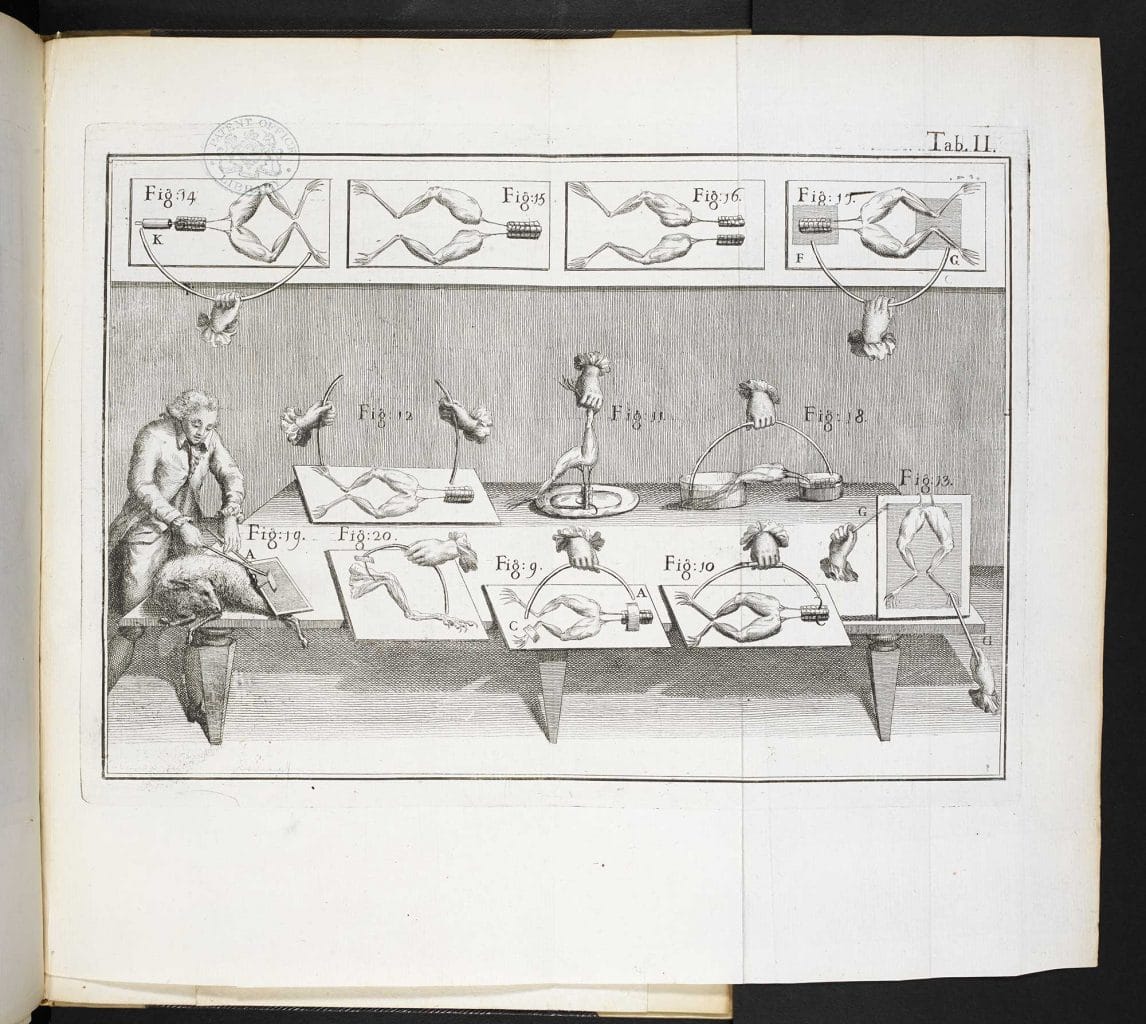

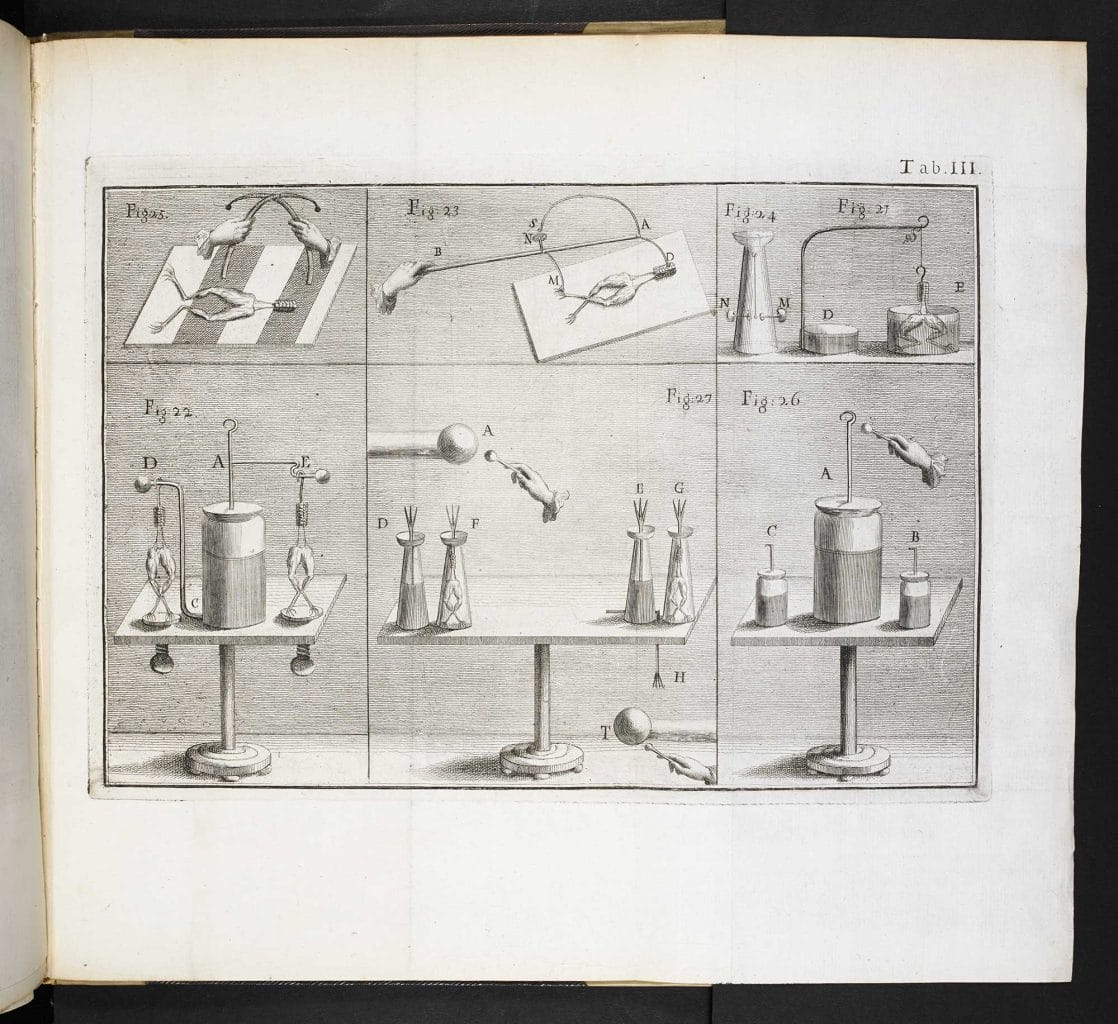

Mary was clearly influenced by current debates about the reach of science and so-called ‘galvanic’ experiments with electricity (which it was thought might contain the secret to creating life). The brooding influence of the Swiss landscape is also clear, and helps give this distinctively Gothic novel its atmospheric gloominess. But it is the book’s powerful sense of humanity that gives it real life – the scientist appalled by the consequences of his attempt to play God; the tragic figure of the Creature, cursed to be feared and hated by humans who can never accept him.

As well as inspiring any number of reinventions – it is sometimes regarded as the first ever science fiction novel, and has been translated into countless languages – Frankenstein is one of the finest creations of its era. In our own time, full of debates about the ethical and philosophical implications of artificial intelligence, it seems more timely than ever.

Life after death

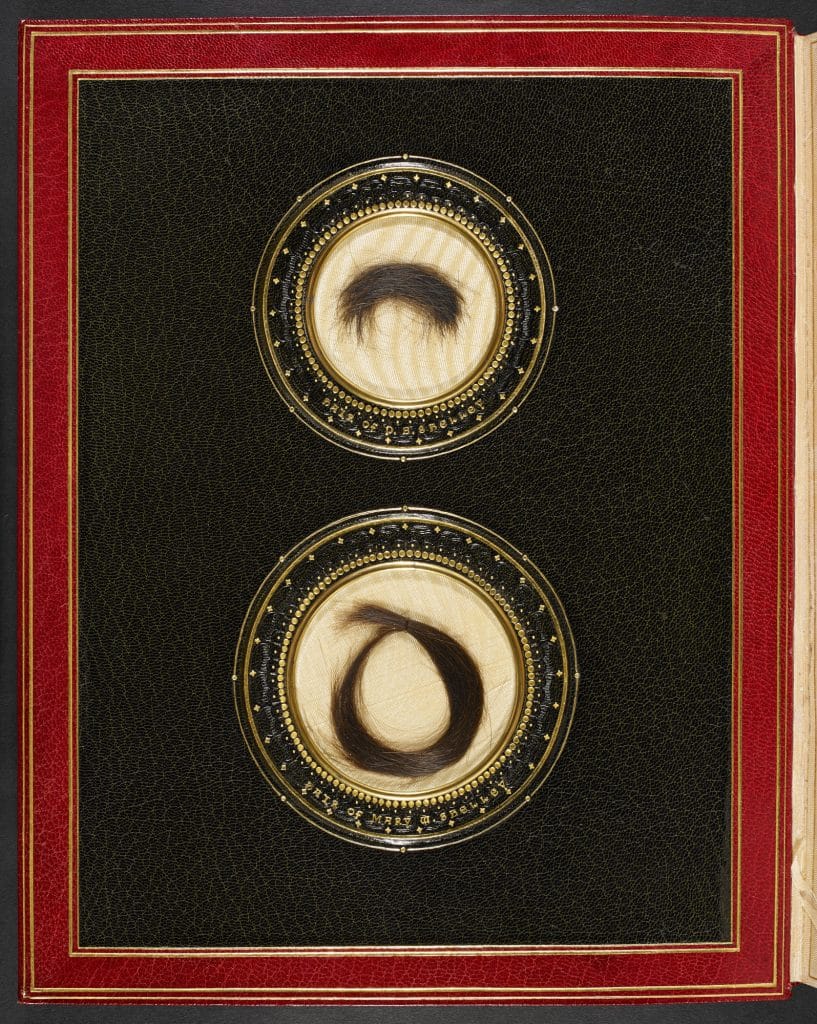

Though Mary and Percy finally married in November 1816 and continued to travel in Italy, their life together was cut brutally short in 1822, when he drowned after the small boat he was piloting was caught in a storm and overturned. Though deeply traumatised, Mary resolved to bring up their sole surviving son, Percy, as best she could (William, her first son, had died of Malaria in June 1819), and also do her utmost to secure her husband’s poetic reputation. She published a volume of his poems in 1824, following it with a painstakingly complete edition in 1839.

She also continued her own writing. A novella called Matilda – a fictional account of the incestuous love between a father and his daughter – was withheld because of the risk of scandal (it was not eventually published until 1959), but other works made Shelley a successful literary figure. Her novel The Last Man (1826), nearly as bold in its premise as Frankenstein, is an apocalyptic tale of a survivor of a deadly plague set in the 21st century.

As well as writing literary criticism and more travel books, and experimenting with short stories, she ranged more widely, too – The Fortunes of Perkin Warbeck (1830) is a novel about the struggle for political power in 15th-century England, while her novels Lodore (1835) and Falkner (1837) take aim at the restrictions of the emerging Victorian class system. As a brilliantly unconventional woman attempting to lead an independent creative, financial and sexual life – she never married again – Shelley must have felt plenty of affinity with the subject.

Mary Shelley died in 1851 of a brain tumour, and following her own wishes she was buried alongside the remains of her parents. In the years following her death, her reputation waned in comparison with her husband’s, and – ironically – he was credited for a long time with having written large sections of Frankenstein. Only in recent decades has she has been acclaimed as the startlingly original talent she was.

Written by: Andrew Dickson

This text is available under the Creative Commons License.