A new exhibition celebrating the famous Chinese poet, scholar and artist Mu Xin, and his love affair with English literature. Featuring manuscript of Virginia Woolf, Oscar Wilde, Lord Byron and Charles Lamb.

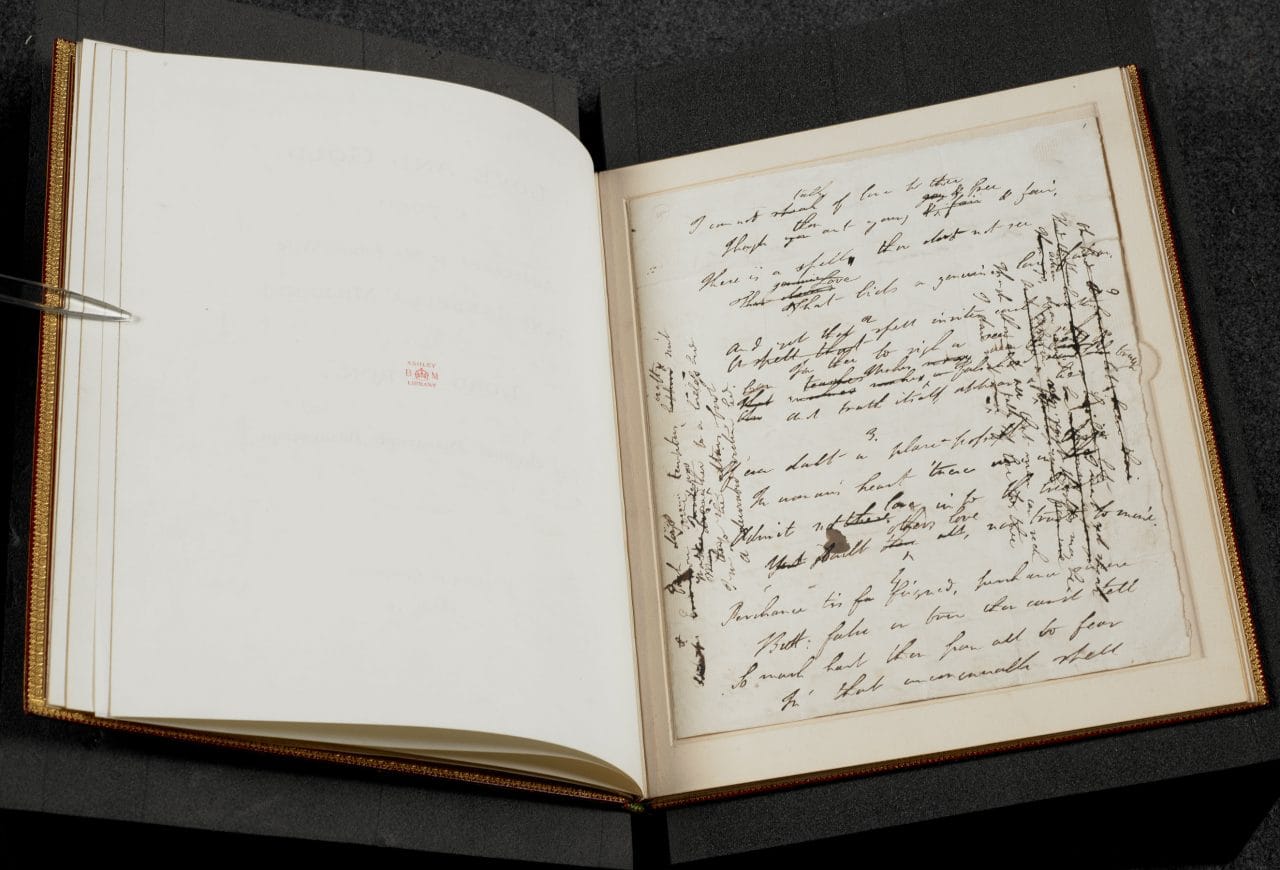

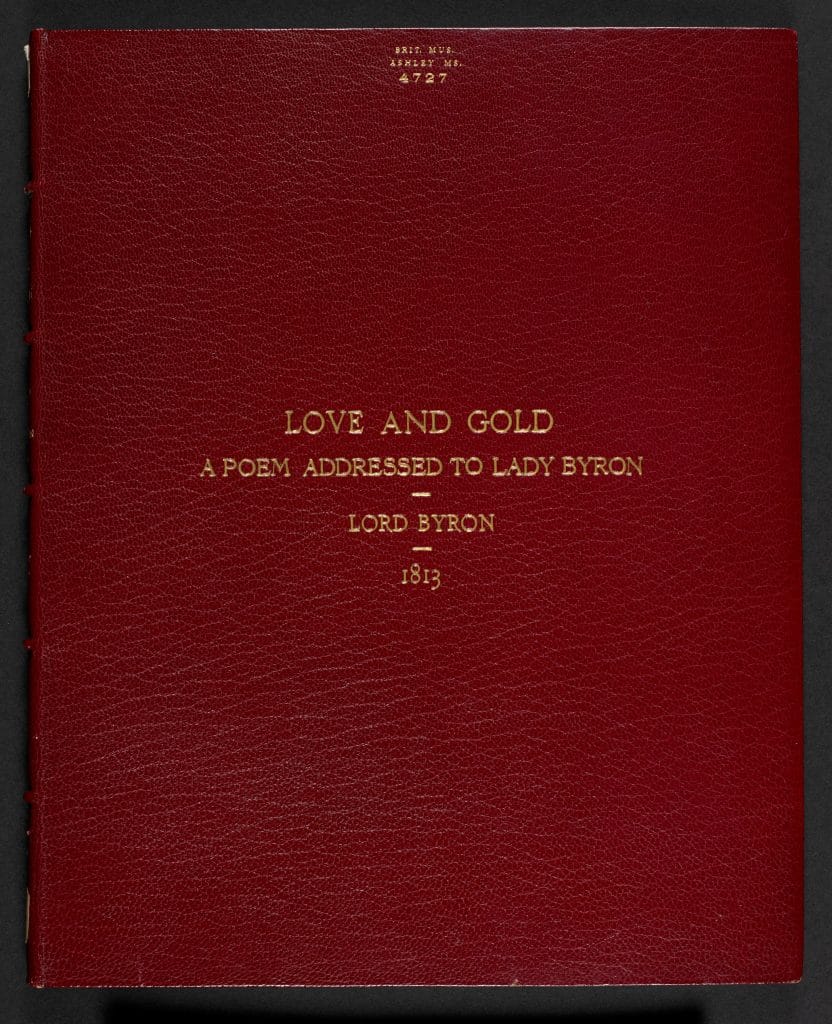

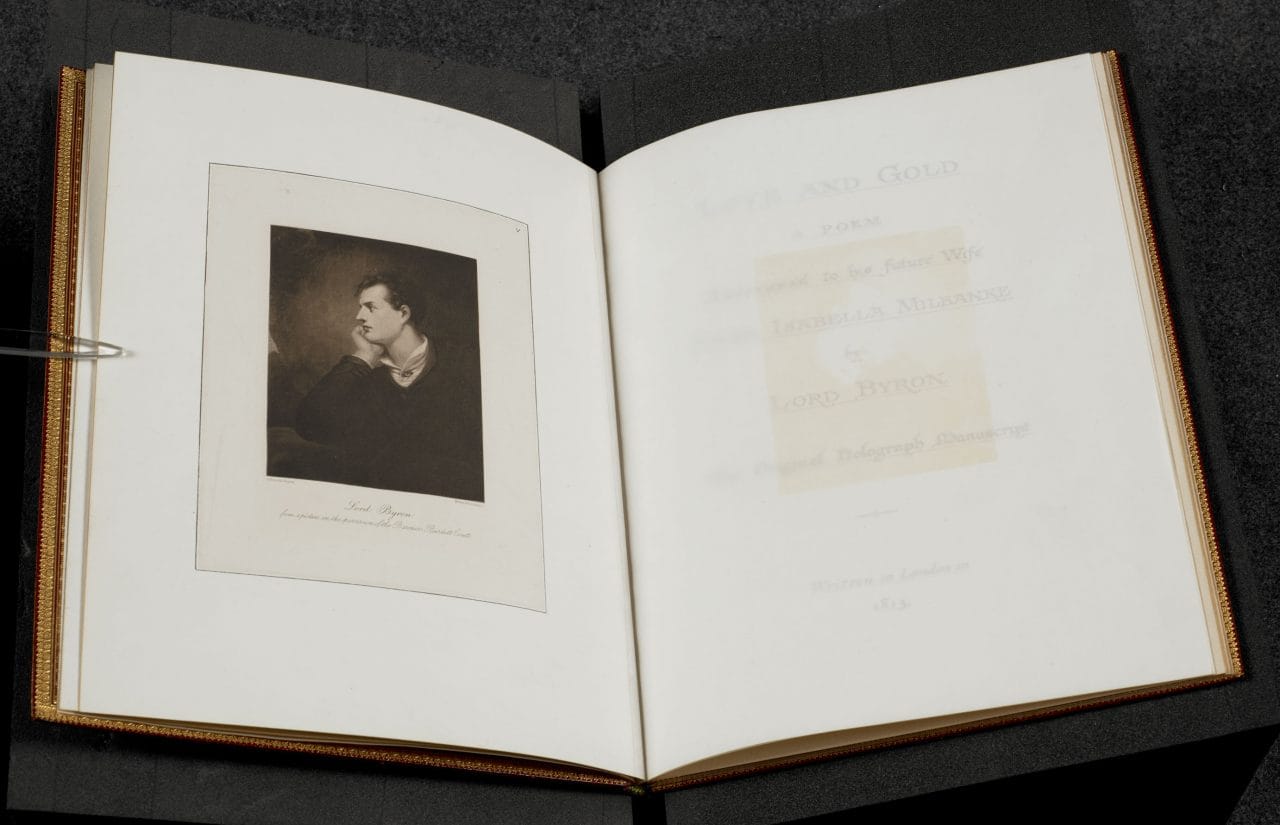

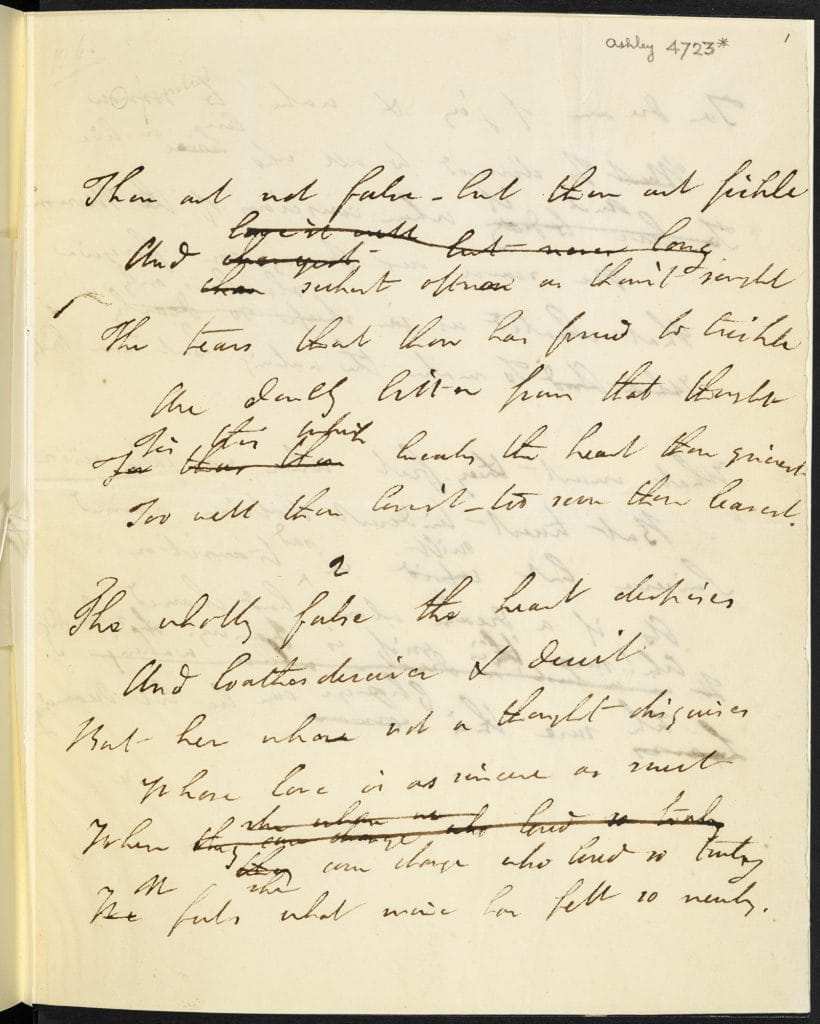

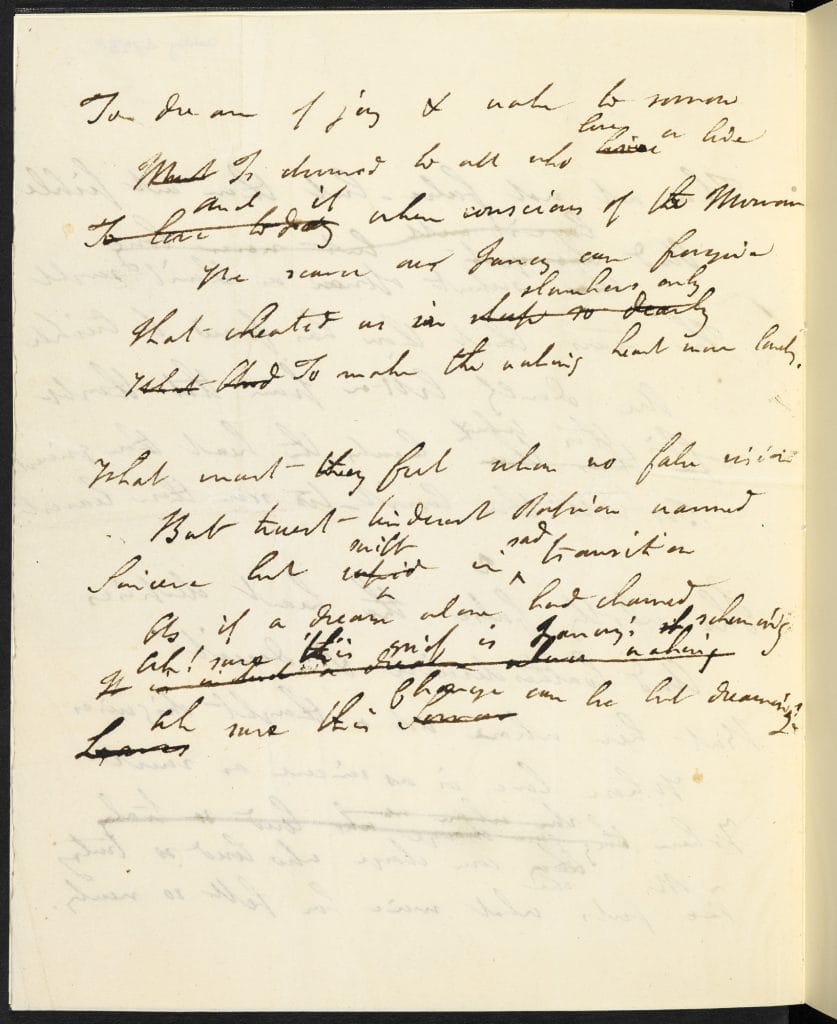

Lord Byron’s ‘Love and Gold’

出版日期: 1812-1813 文学时期: Romantic 类型: Romantic poetry

Lord Byron’s poem ‘Love and Gold’ is generally thought to have been composed in 1812-1813. It is a poem of both seduction and deception, in which the poet pretends to be unworthy of the object of his affection. It has generated a degree of speculation, because no-one can identify precisely who it was written about. At that time, when Byron was in his mid-twenties, the notoriously promiscuous poet was linked to a number of possible lovers.

What is ‘Love and Gold’ about?

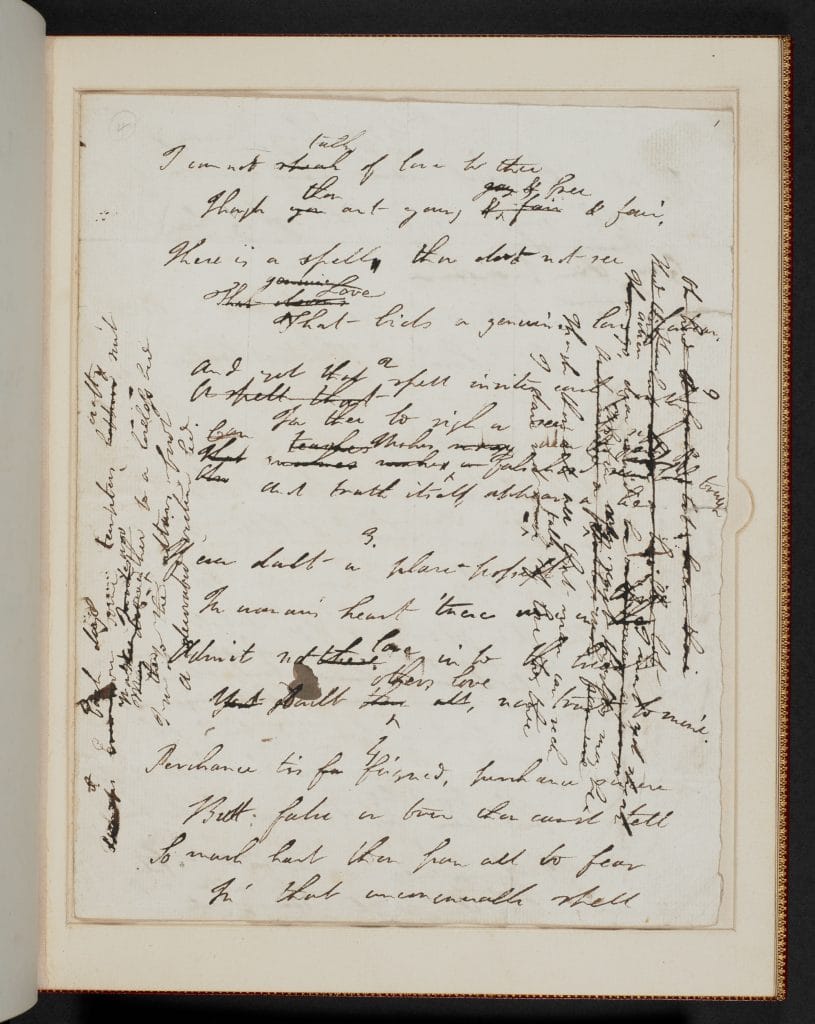

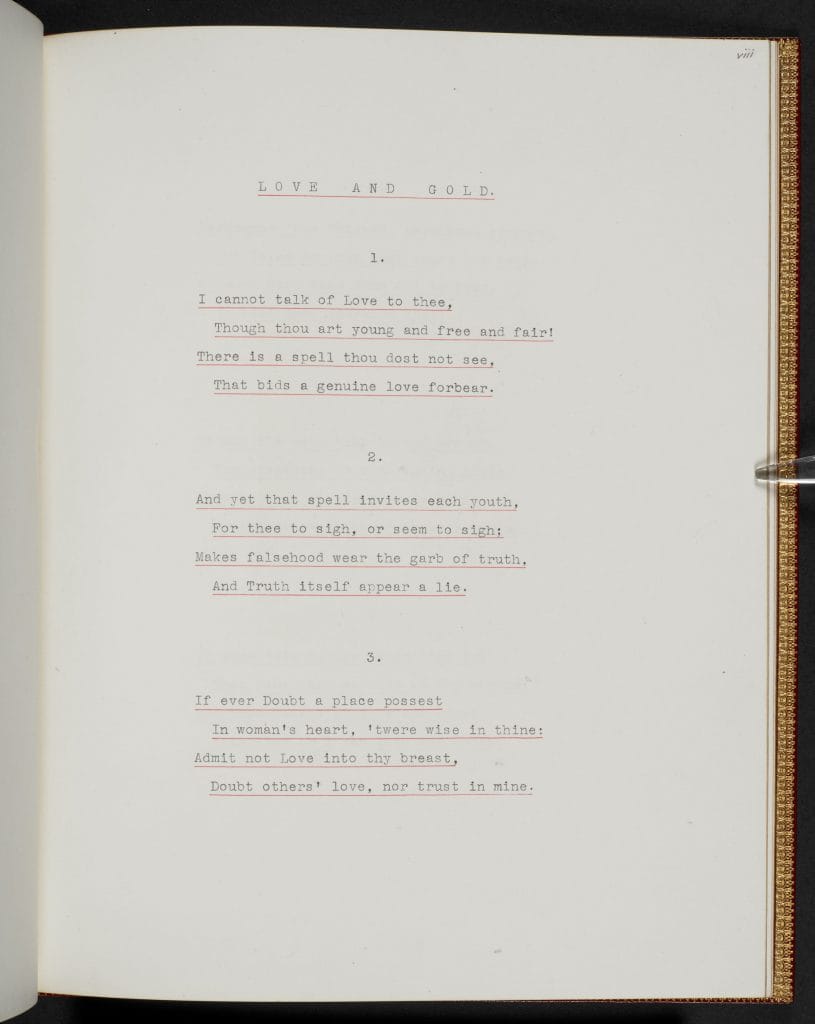

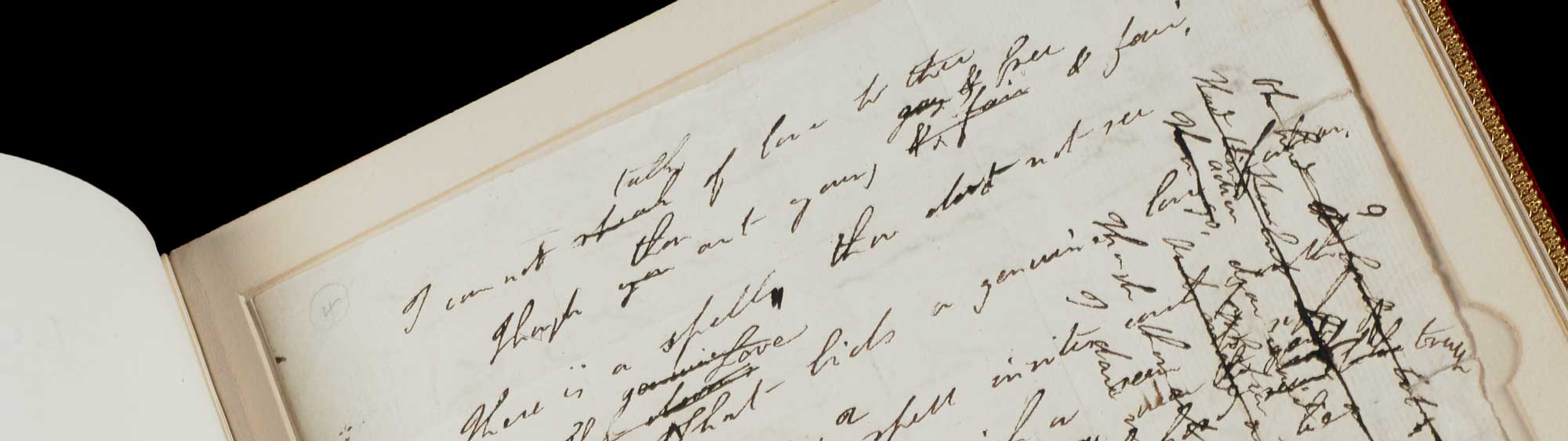

I

I cannot talk of Love to thee,

Though thou art young and free and fair!

There is a spell thou dost not see,

That bids a genuine love despair.

II

And yet that spell invites each youth,

For thee to sigh, or seem to sigh;

Makes falsehood wear the garb of truth,

And Truth itself appear a lie.

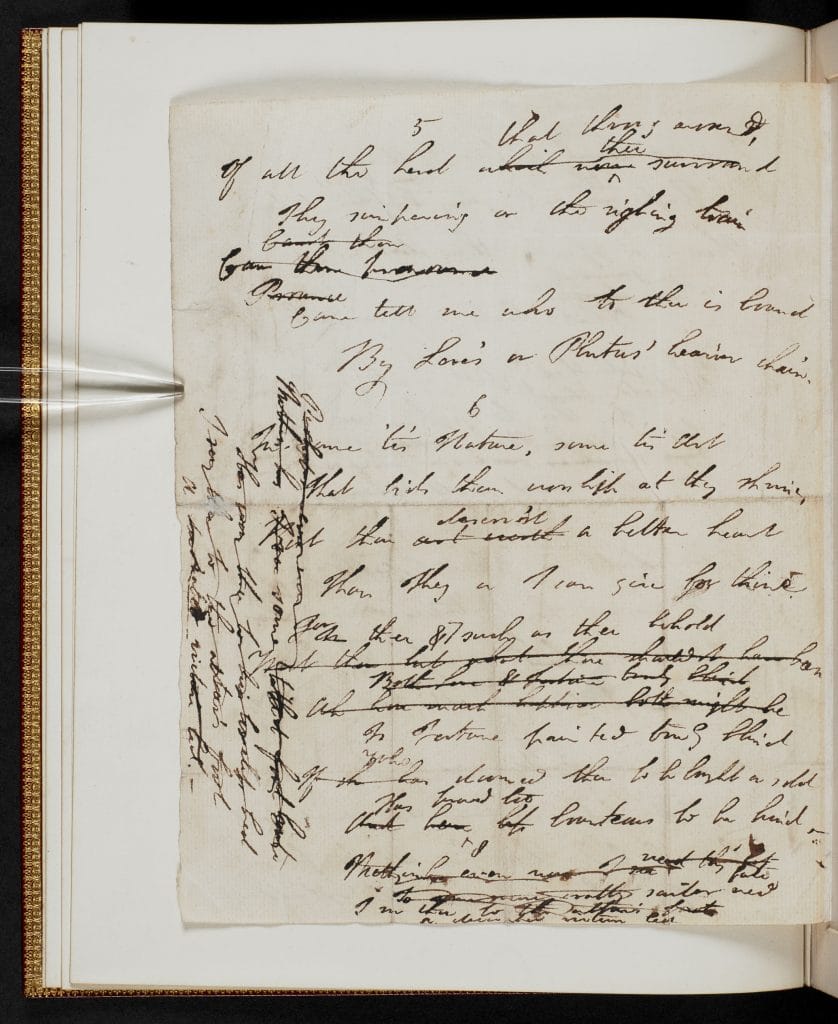

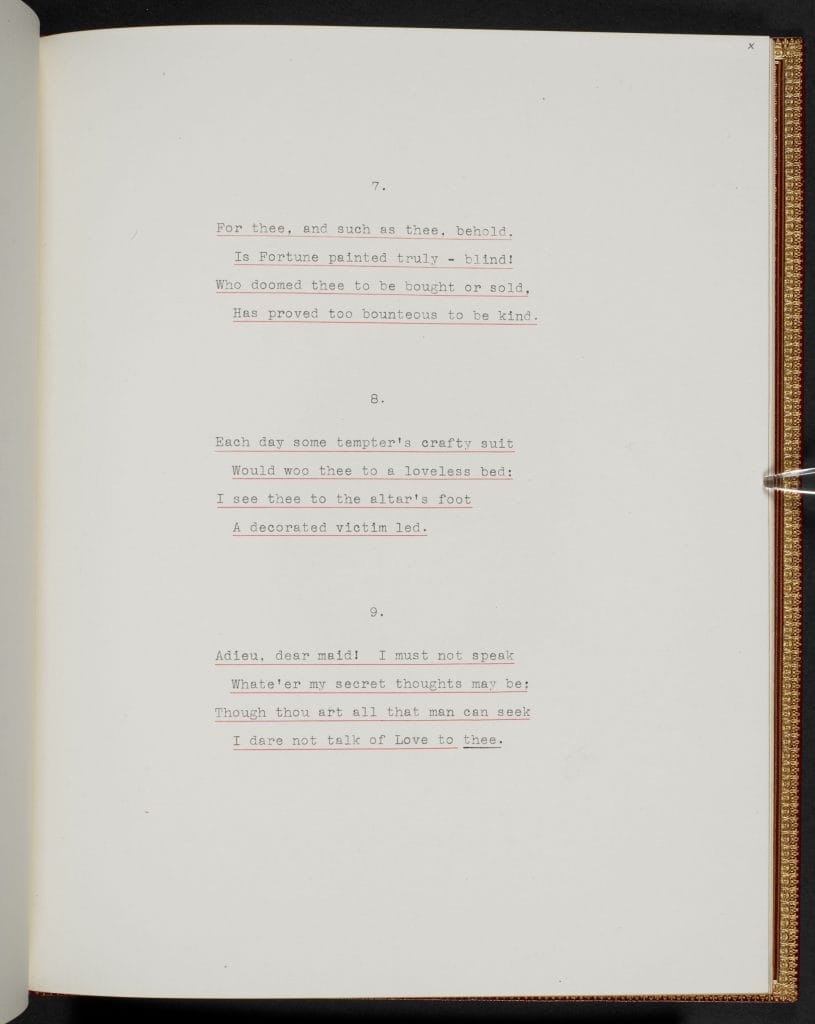

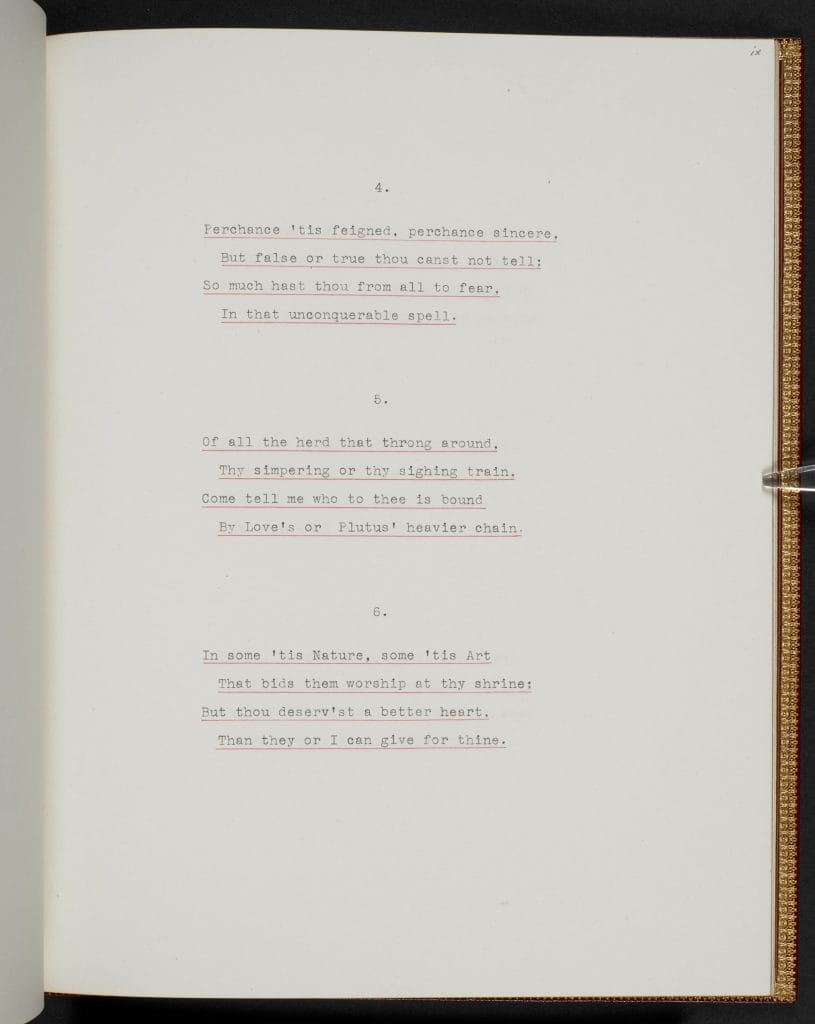

These are the opening words of ‘Love and Gold’, a poem structured in nine four-line stanzas (quatrains), using iambic tetrameter rhythm, and alternate rhyme (abab). It was probably written in the summer of 1813, and its theme is the potential danger involved in courtship. The speaker warns that a rich woman might attract duplicitous, sycophantic suitors motivated merely by money (see the reference in l.20 to Plutus, the god of wealth in ancient Greece). She needs to be on her guard – even against him: ‘Admit not Love into thy breast,/Doubt others’ love, nor trust in mine’ (ll.11-12). The candid and seemingly concerned poet asks how a lady can be sure of ‘genuine love’ (l.4) when a man appears to revere her and worship at her ‘shrine’ (l.22). Using a chilling metaphor, in the closing stanzas the poet compares her to a sacrificial victim being led to the altar (ll.31-32).

VIII

Each day some tempter’s crafty suit

Would woo thee to a loveless bed:

I see thee to the altar’s foot

A decorated victim led.

IX

Adieu, dear maid! I must not speak

my secret thoughts may be;

Though thou art all that man can seek

I dare not talk of Love to thee.

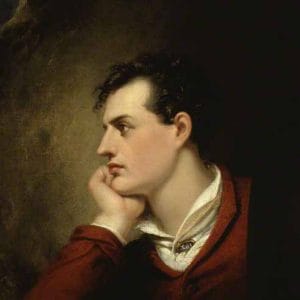

Who was Lord Byron?

The historian and politician Thomas Babington Macaulay said of Byron: ‘He was himself the beginning, the middle, and end of all his own poetry…’ Certainly the poet’s personal dilemmas were conveyed and scrutinized in many of his works, and readers and scholars to this day turn to his verse to decipher the man.

George Gordon, 6th Lord Byron (1788-1824), achieved celebrity status virtually overnight following the publication of the first two Cantos of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (1812). He became a living legend; a flamboyant figure whose poetry reflected his fluctuating emotions and ambivalent sexual desires, and his yearning to experience life to the full.

In turns, Byron could be facetious and barbed or compassionate and sensitive. His personal contradictions reflect a fundamental tension in Romanticism: a sense of the limitless potential of mankind, but also an acute awareness that existence is transitory and ideals may not be attainable. Childe Harold described the wanderings of a young, disillusioned man and set a trend for a literary stereotype: the melancholy, dark, brooding, rebellious ‘Byronic hero’ who seemed to represent his generation.

First Flames

Byron’s letters, journals and early poems provide fascinating glimpses into his childhood and adolescent inclinations. At the age of seven he had overwhelming feelings for a distant cousin, Mary Duff: ‘first of flames, before most people begin to burn’. In 1800 a cousin, Margaret Parker, won his affections, inspiring his ‘first dash into poetry’. She died in 1802 and is commemorated in the poem ‘On the Death of a Young Lady’. Byron became infatuated with yet another cousin, Mary Chaworth, the subject of ‘Hills of Annesley’ (1805), ‘The Adieu’ (1807), ‘Stanzas to a Lady on Leaving England’ (1809) and ‘The Dream’ (1816). He said: ‘She was the beau idéal of all that my youthful fancy could paint of beautiful; and I have taken all my fables about the celestial nature of women from the perfection my imagination created in her – I say created, for I found her, like the rest of the sex, any thing but angelic.’

Young Byron was also attracted to boys. Studying at Harrow, from 1801-1805, he had a ‘cluster of romantic friendships’ with fellow-students. Biographer Fiona McCarthy notes his ‘dawning consciousness of his dual nature’, and ‘mingled fascination and revulsion’ about homosexuality. At Cambridge (1805-1807) Byron fell in love with a choirboy, John Edleston, whose untimely death in 1811 is lamented in a series of tender elegies, the ‘Thyrza’ cycle.

An attachment to Julia Leacroft almost led to a duel between Byron and her brother. It is thought that she inspired ‘To Lesbia’. In 1807, Byron told his friend Edward Long that he had been accused of seducing ‘no less than 14 Damsels, (including my mother’s maids) besides sundry Matrons and Widows’. By 1809 he had sired at least two children: one by a London prostitute; one by a servant.

‘Mad, bad, and dangerous to know’

Byron’s creative efforts enthralled adoring female fans, who copied favourite pieces into their commonplace books. Over the years his name was to be coupled with many women, including the eccentric Lady Caroline Lamb in 1812 – who famously declared that he was ‘mad, bad, and dangerous to know’! ‘Thou Art Not False But Thou Art Fickle’ was written in 1813 towards the end of their affair, when he had already embarked upon other dalliances.

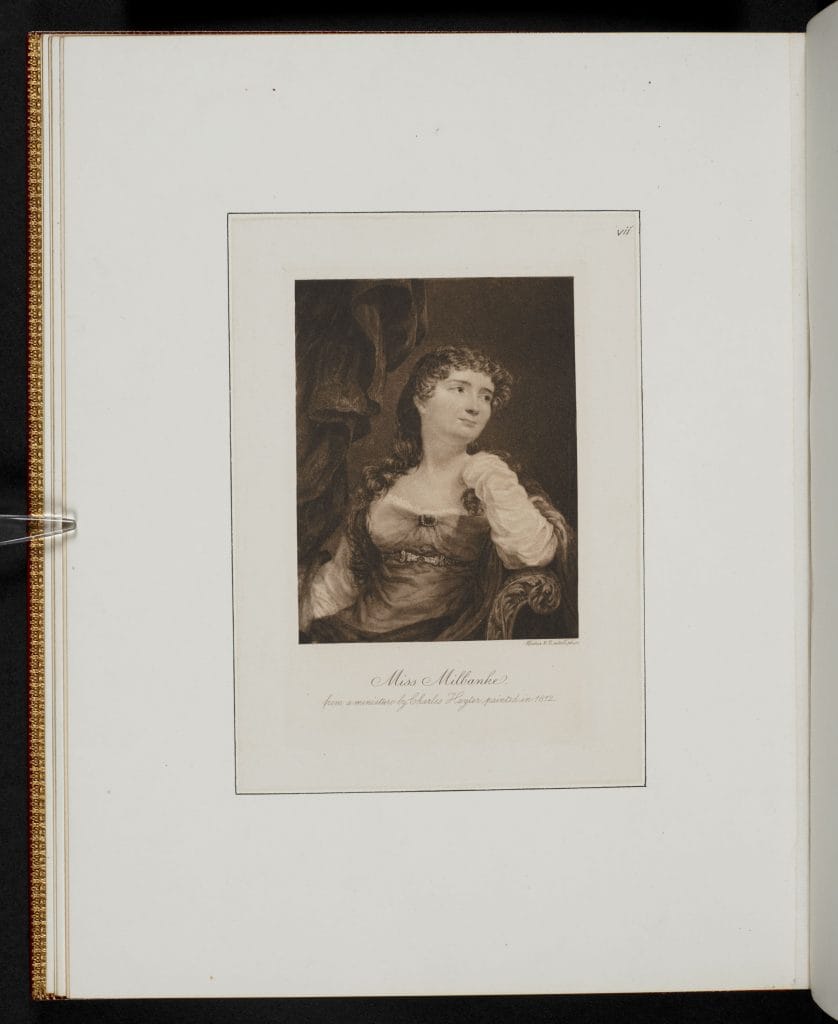

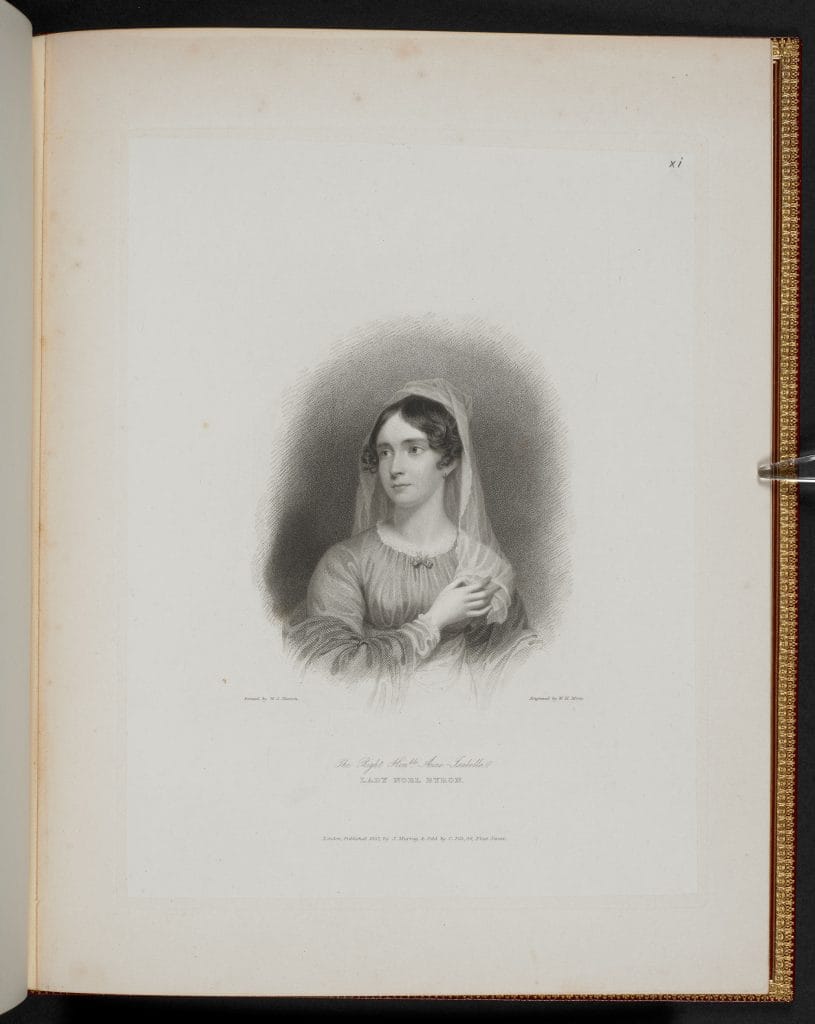

As Byron’s romantic entanglements were so multifarious, it is unsurprising that the addressees in his works cannot always be named with conviction. ‘Love and Gold’ may have been for Annabella Milbanke. They married in 1815, but their relationship was a disaster. There were rumours about incest with his half-sister, Augusta, and about marital violence. Annabella obtained a separation. Facing abuse from the now-hostile public, Byron wrote ‘To Augusta’: ‘When all around grew drear and dark … Thou wert the solitary star/Which rose and set not to the last.’ Renowned for his sexual exploits, and dogged by debt and scandal, he quitted Britain in 1816 and did not return. In January 1817 his daughter Allegra was born, to Claire Claremont, the stepsister of Mary Shelley.

In ll.17-18 of ‘Love and Gold’ Byron describes ‘the herd that throng around/Thy simpering or thy sighing train’, and on November 10th 1813 he wrote to Annabella: ‘By the bye, you won’t take fright when we meet will you? and imagine that I am about to add to your thousand and one pretendants?’

Martin Garrett notes Annabella as a possible recipient of the poem, but also mentions Lady Adelaide Forbes (1789-1858) and Margaret Mercer Elphinstone (1788-1867). Lady Adelaide was the daughter of the 6th Earl of Granard. Fiona MacCarthy states that she and Byron met regularly at London parties, but ‘the relationship had not progressed beyond “the every-day flirtation of every-day people” over a light supper accompanied by spirited social discussion of the merits of white soup and plovers’ eggs’. Byron scholar Peter Cochran veers towards Mercer Elphinstone, a much-pursued heiress who was known as ‘the Fops’ Despair’ ‘because she would be the biggest golden dolly they could get, except that they couldn’t get her’. He adds that she seems to have liked Byron, but kept him at a safe distance; and he points out that the reference to Plutus in l.20 indicates someone very wealthy.

Such speculation is thought-provoking, and demonstrates why Byron’s work has continued to captivate readers and invite analysis.

脚注

Written by: Stephanie Forward

The text in this article is available under the (Creative Commons License).