Charles Dickens’s Nicholas Nickleby

出版日期: 1839 文学时期: Victorian 类型: Victorian

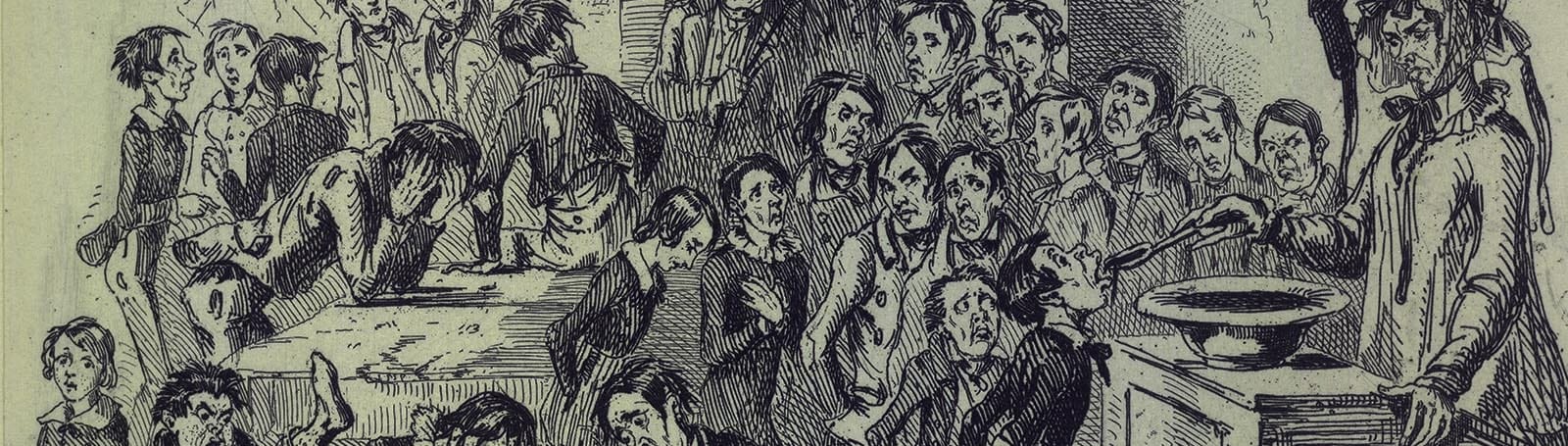

Charles Dickens’s Nicholas Nickleby was first published in monthly parts between March 1838 and September 1839. Nicholas’s adventures take him to the nightmarish school Dotheboys Hall, home of the brutal schoolmaster Wackford Squeers – one of Dickens’s greatest grotesques. It was Dickens’s intention to reveal to the public the horrors of Yorkshire’s notorious boarding schools, where parents would dump their unwanted children for indefinite periods. The lack of hygiene and the inhumane treatment of pupils was a source of great scandal at the time.

What is Nicholas Nickleby about?

This long and involved novel tells the story of a family left destitute by the death of their father, Mr Nickleby. Nicholas, his mother and his sister, turn in desperation to their uncle, Ralph Nickleby, who proves to be a disreputable tyrant.

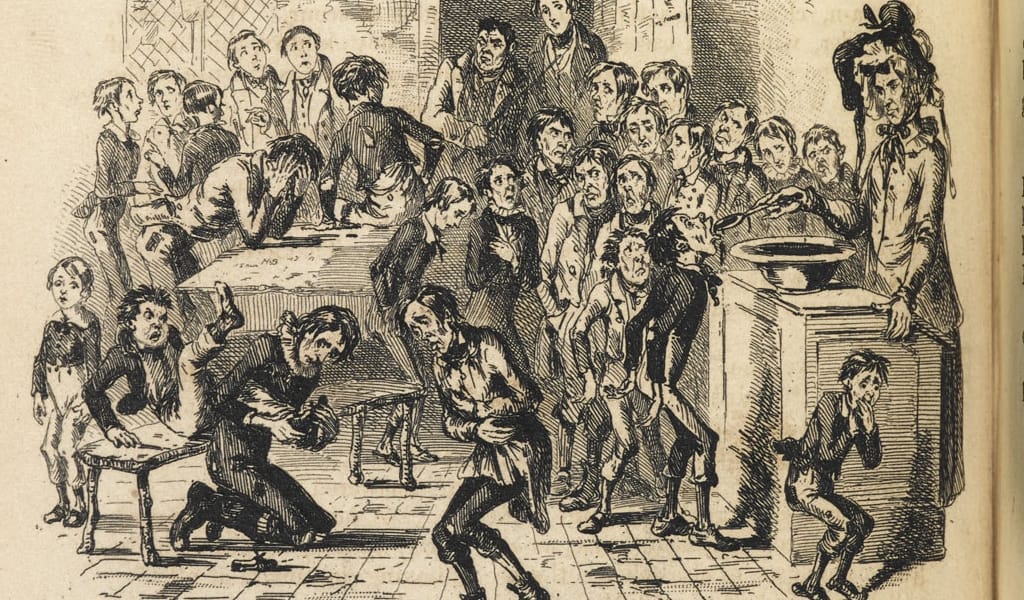

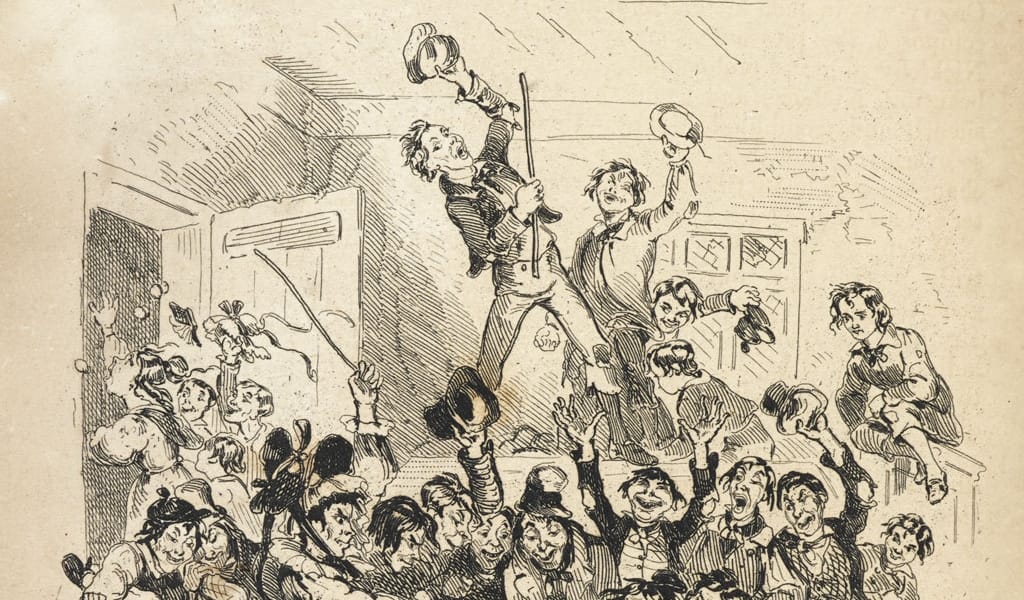

Angered by Nicholas’s rebellious spirit, Ralph sends him to work as a schoolmaster at Dotheboys Hall, a brutal Yorkshire school run by the evil Wackford Squeers. Nicholas is appalled by the treatment of the school’s pupils, in particular a frail and simple-minded boy called Smike. After giving Squeers a taste of his own medicine in the form of a severe thrashing, Nicholas and Smike run away from the school and join a troupe of travelling entertainers.

Meanwhile, in London, uncle Ralph is planning to deliver his niece into the clutches of the despicable Sir Mulberry Hawk. News of his plan reaches Nicholas, who returns to London to rescue his sister and make a home for her and their mother. Smike dies of consumption and is revealed as the son of Ralph Nickleby. The disgraced uncle hangs himself; justice is done; and the Nickleby family finds tranquillity at last.

What does the manuscript reveal?

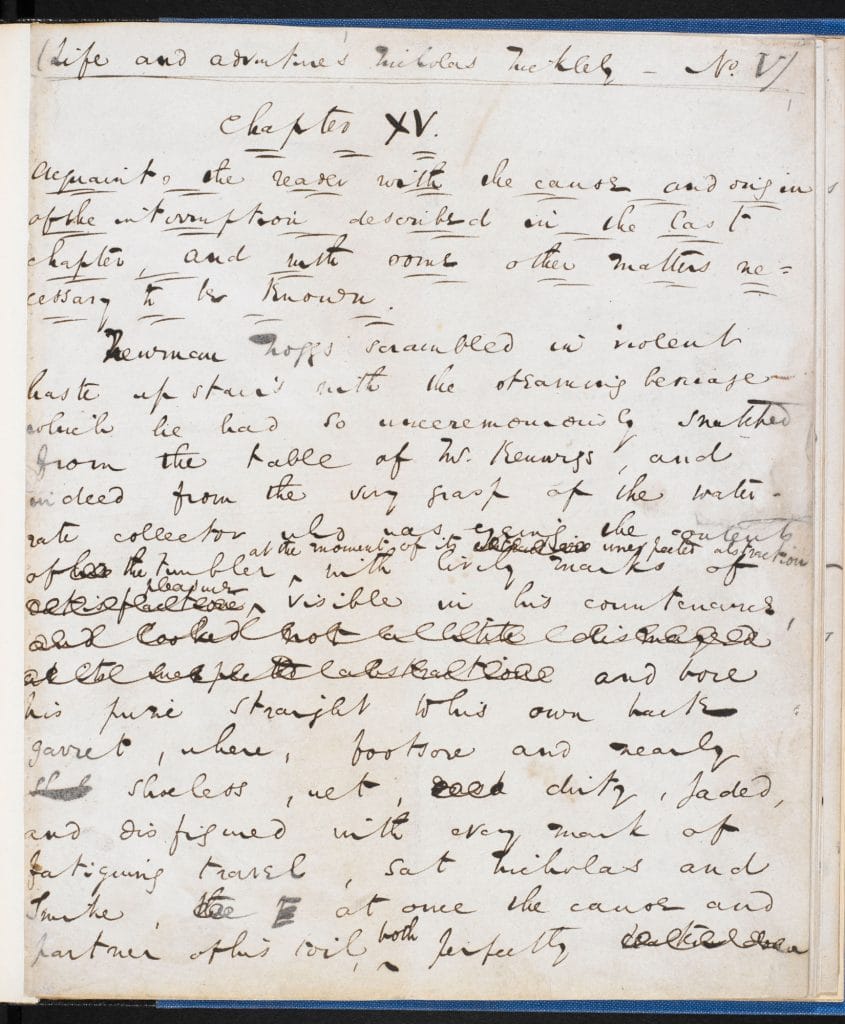

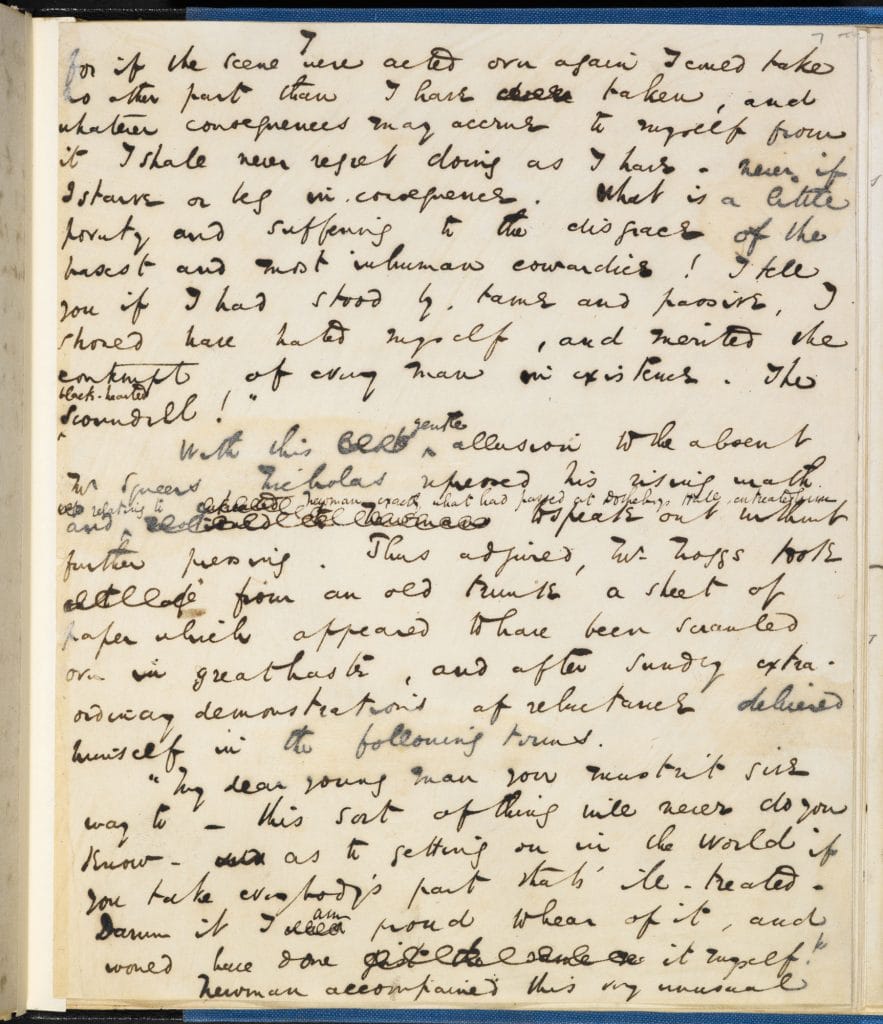

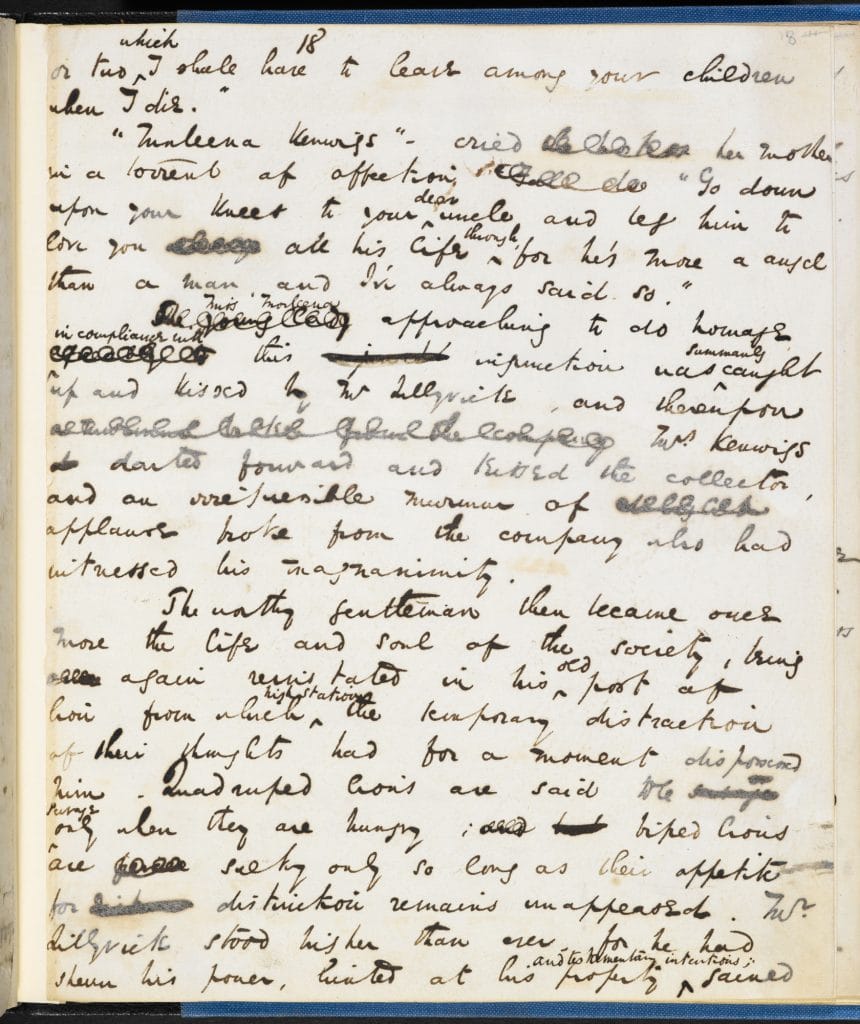

Like the handwritten drafts of other authors, the main fascination of the autograph copy of Nicholas Nickleby lies in the corrections and alterations that reveal Dickens’s creative process at work.

This page comes from the first part of Chapter 15, and begins in the middle of a letter written by Fanny Squeers, daughter of Dotheboys Hall’s violent headmaster. She is giving Nicholas’s uncle an exaggerated account of her father’s beating by his ‘nevew’. The letter is full of such spelling mistakes and grammatical errors, so some of Dickens’s corrections are actually ‘incorrections’!

For example, Fanny writes that Nicholas ‘not having been apprehended by the constables is supposed to have been took up by some stage-coach’. Dickens instinctively used the correct grammar, ‘to have been taken up…’, but changes it to fit Fanny’s character. Why he also substituted ‘constables’ for ‘officers’ is not so clear.

Nicholas Nickleby, extract from chapter 15. Read by David Horovitch. Courtesy of Naxos Audiobooks.

Bowes Academy and the Yorkshire schools

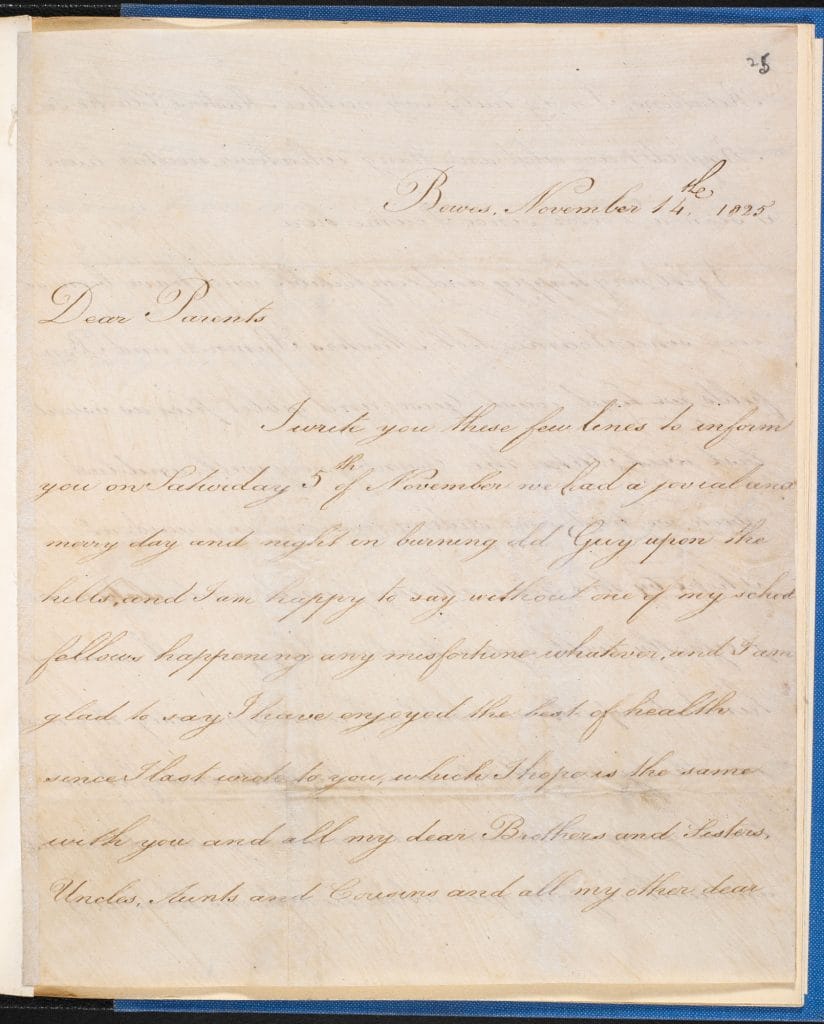

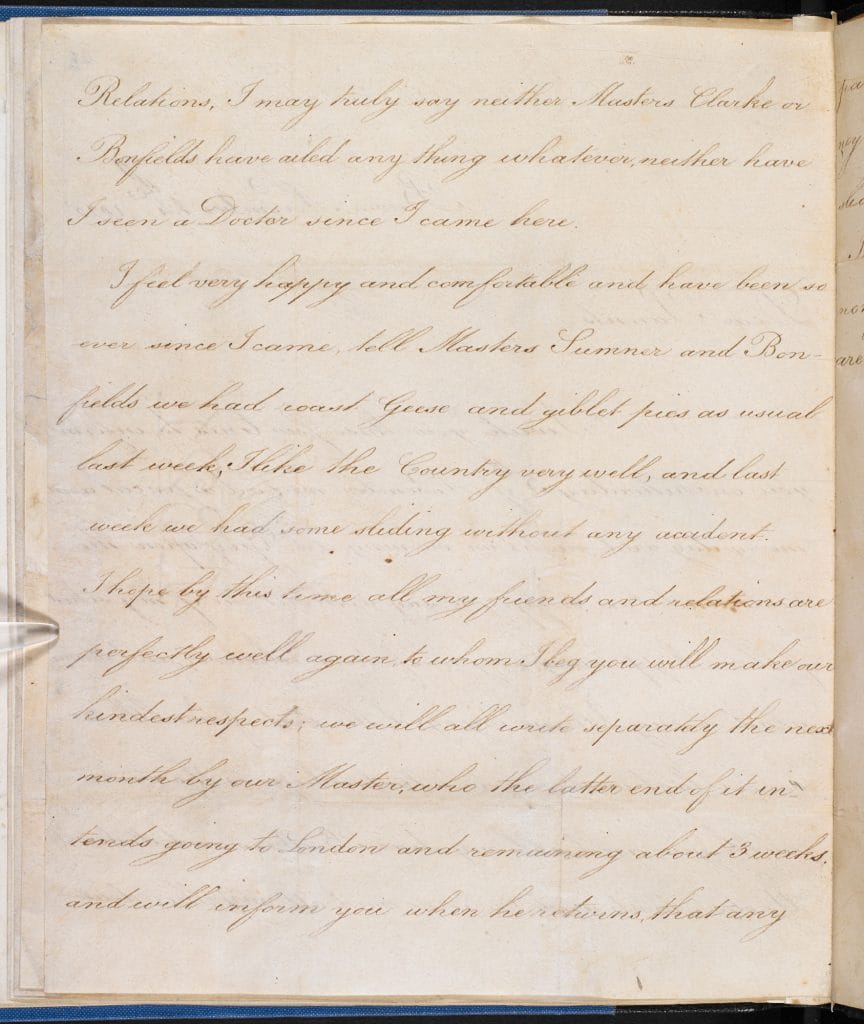

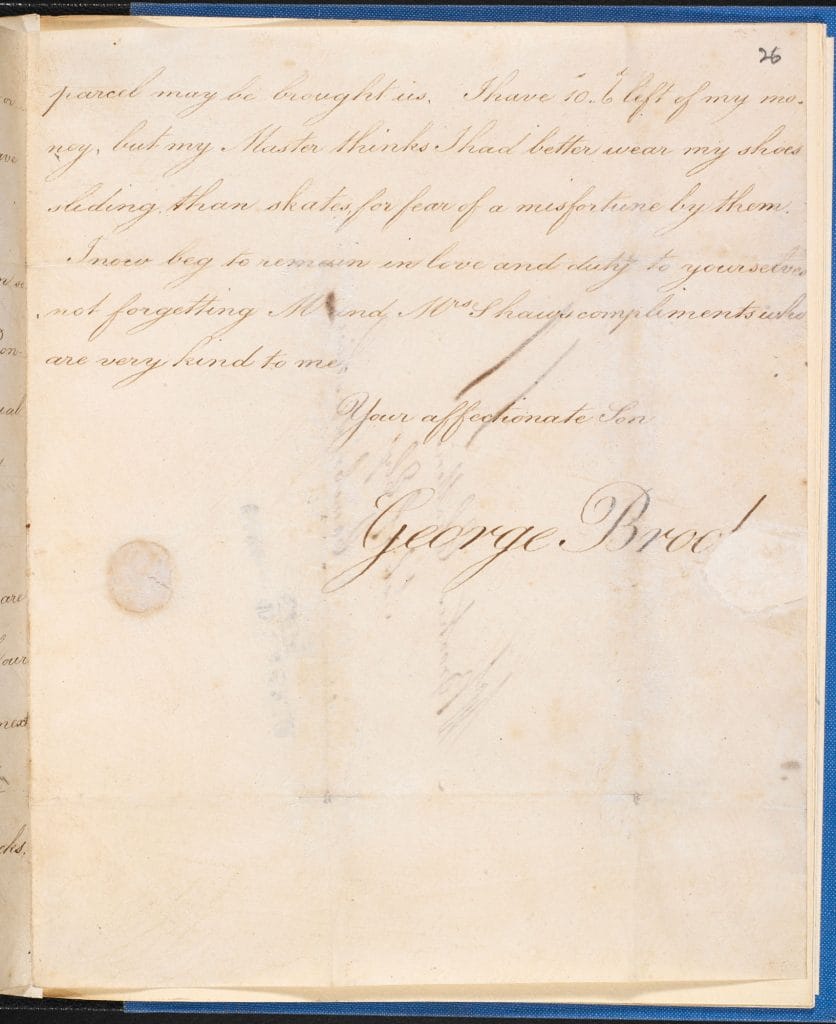

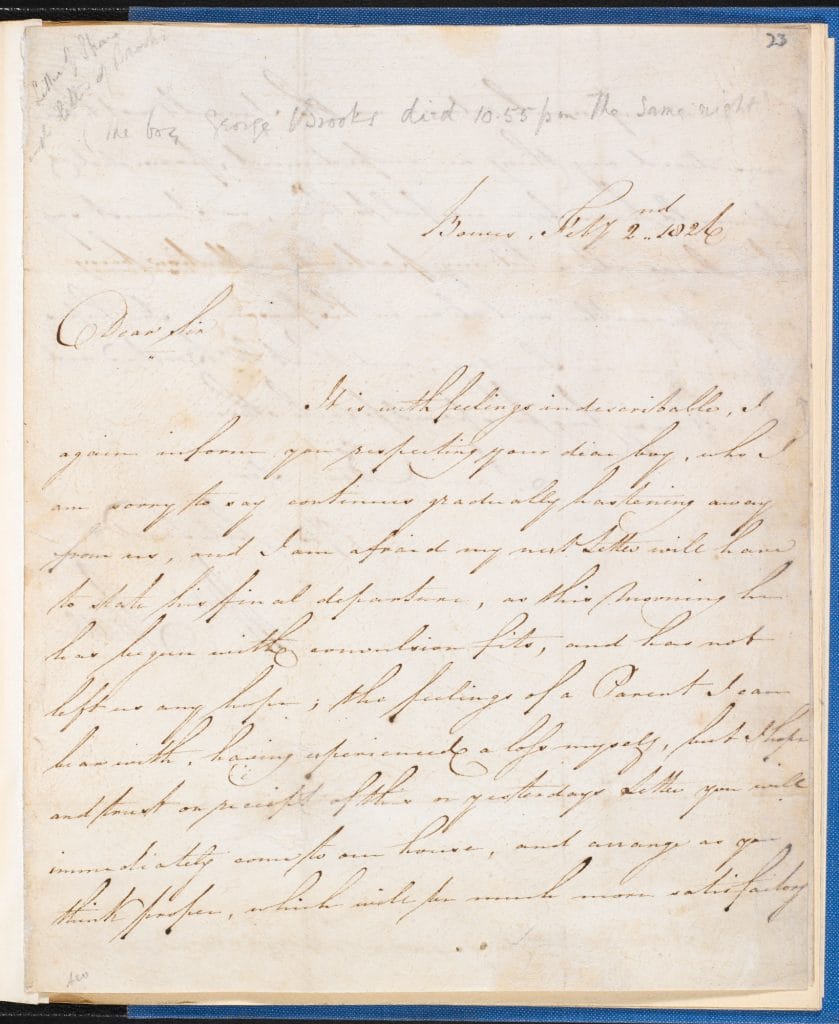

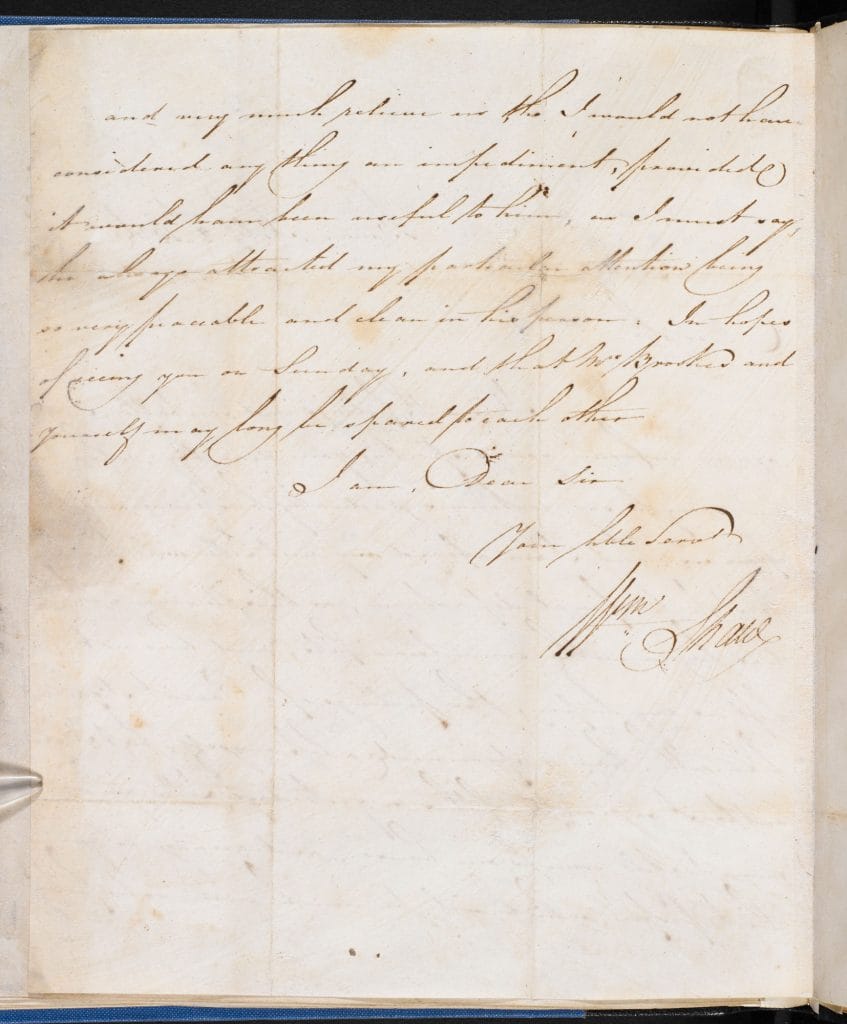

The pages from Nicholas Nickleby are bound in a volume with two fascinating letters.

The letters are highly relevant to the novel. They were written from the Bowes Academy, a school in Yorkshire, between 1825 and 1826. Both are to the parents of George Brooks, one from the boy himself and the other from the headmaster, William Shaw. Brooks writes he ‘feels very happy and comfortable’, and that he has not needed to see a doctor; tragically, the letter from Shaw just three months later breaks the news of Brooks’s failing health and imminent death. The facts surrounding Brooks’s illness and death are unknown.

In 1823, Shaw had been prosecuted for beatings and neglect that led to the blinding of two of his pupils. Dickens visited the school in 1838. He found matters little improved, and used William Shaw as his model for the hateful Wackford Squeers.

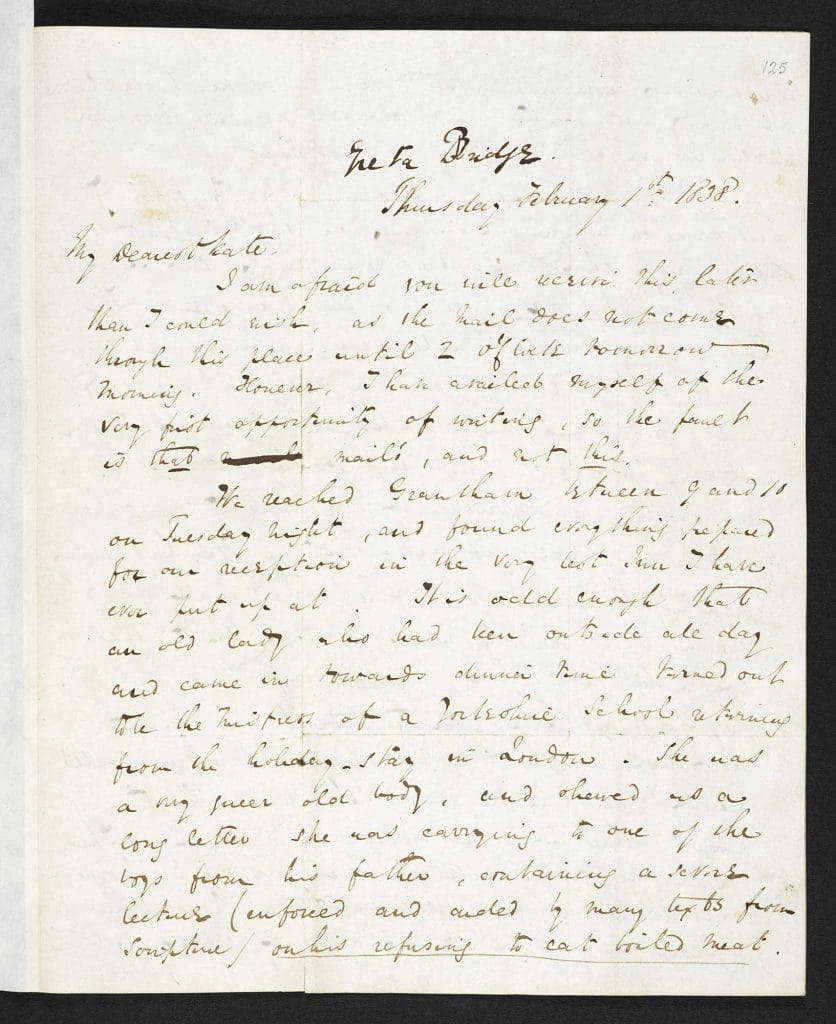

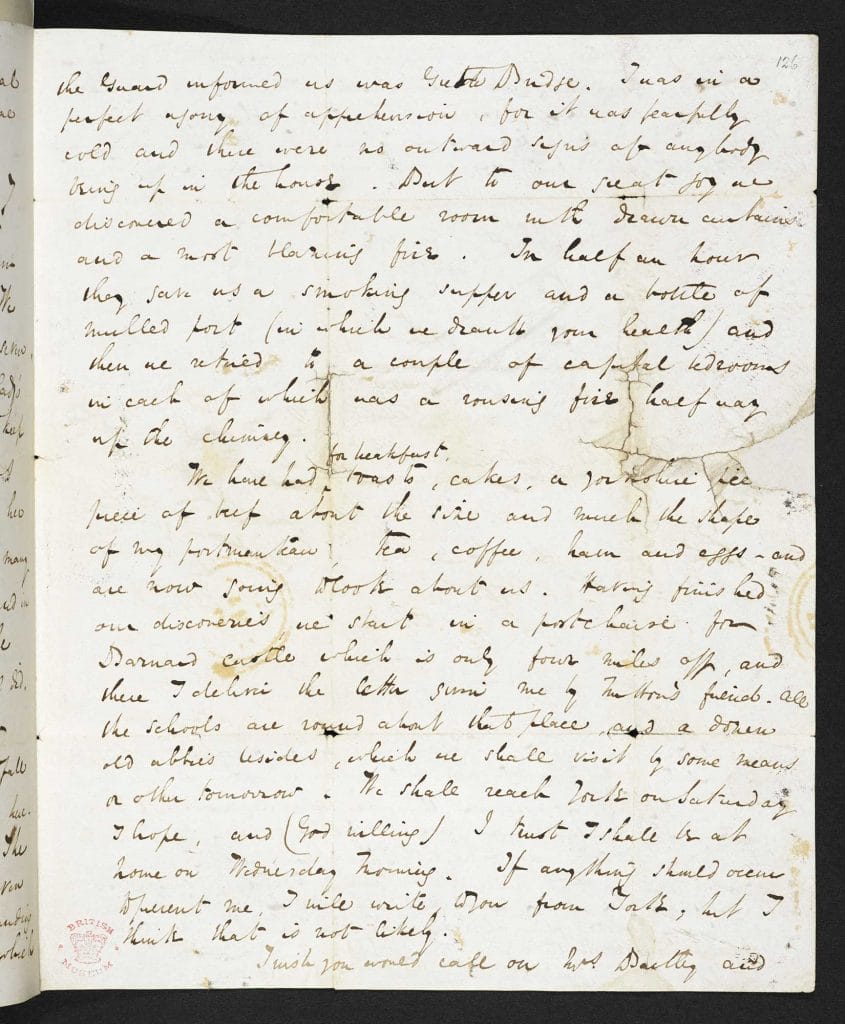

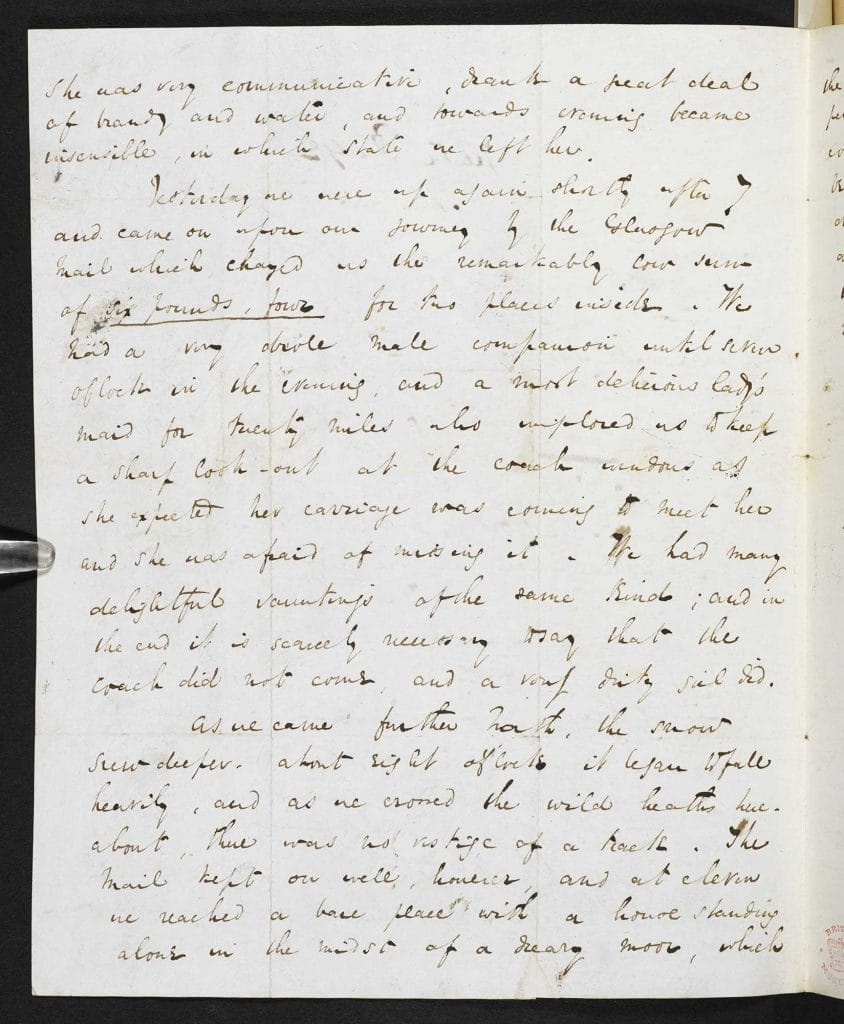

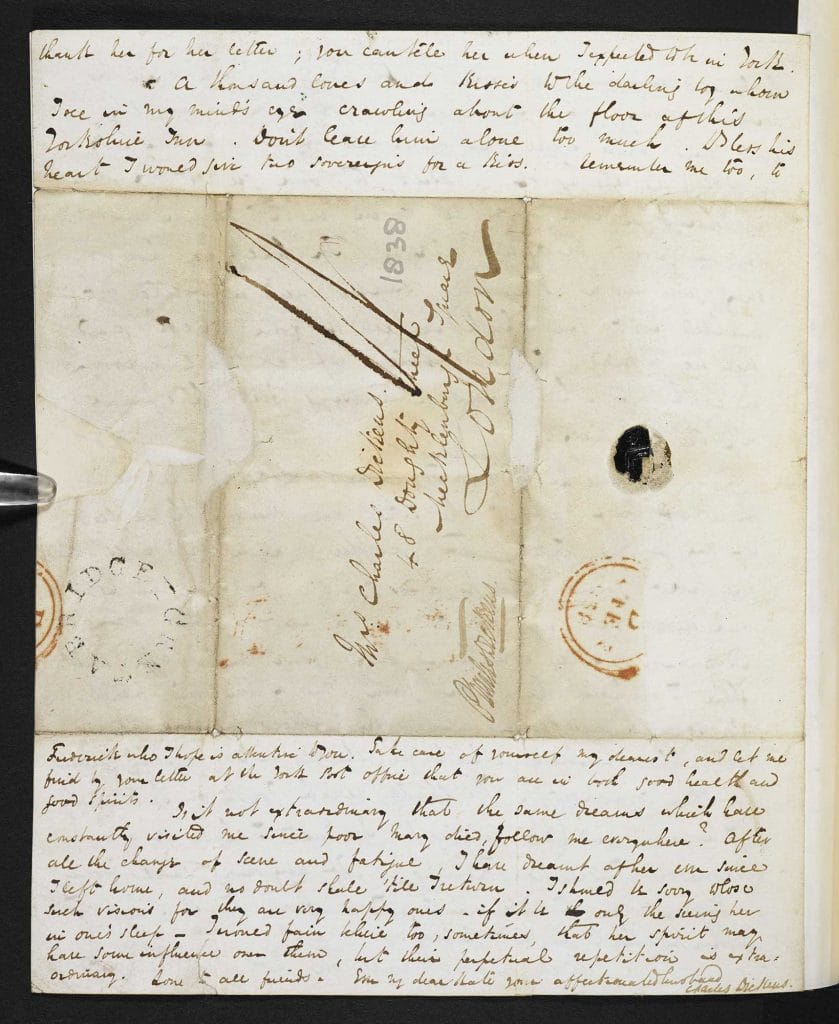

On 30 January 1838 Charles Dickens and his illustrator Hablot Browne (‘Phiz’) set out on a two-day coach ride to Yorkshire to investigate the long-standing scandal of cheap boarding schools. As a child Dickens had heard about these places, which acted as little more than brutal detention centres for unwanted children, and he now wondered whether they might form the subject of his new novel. In this long letter to his wife Catherine, Dickens gives an entertaining account of the journey.

Many of the details Dickens describes gave him ideas for scenes and even characters in Nicholas Nickleby. He and Browne, like the two outside passengers in the novel, spent the first night at the George at Grantham, ‘the very best Inn I have ever put up at’. The Yorkshire schoolmistress, who was carrying a letter to one of her pupils from his father lecturing him on his refusal to eat boiled meat, inspired the pathetic but very funny letter-reading scene in which we hear about Mobbs’s stepmother who ‘took to her bed on hearing that he wouldn’t eat fat’. The ‘most delicious’ lady’s maid became the ‘very fastidious lady’ passenger in Nicholas’s coach who complained loudly about the non-arrival of her carriage.

The heavy snow and intense cold, the increasingly wild, inhospitable landscape, and the apparently deserted inn at Greta Bridge all contributed to the grim atmosphere of the early chapters of the novel. The main difference for the reader is that Dickens was soon sitting down to ‘a blazing fire … a smoking supper and a bottle of mulled port’, but Nicholas has to face the bleak desolation of Dotheboys Hall.

Publication in parts

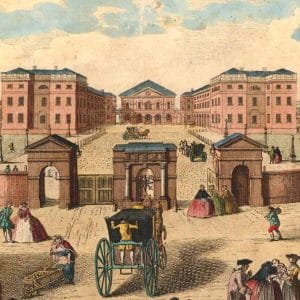

In November 1837, the year after the publication of his first novel, The Pickwick Papers, Charles Dickens signed a contract with the publishers Chapman and Hall for a new novel ‘of a similar character and of the same extent and contents in point of quantity’. Nicholas Nickleby was duly published in 20 monthly parts, or numbers, at a shilling each between March 1838 and September 1839, the last being a double number at two shillings.

Publication in parts was a long-established practice which had the advantage for the publisher of spreading the cost of production over a long period, and for the purchaser of making high-quality, lavishly illustrated fiction affordable. Authors also benefitted from a regular income while they wrote: Dickens received £150 for each monthly instalment of Nicholas Nickleby. It became an important form of publication used by many of the most eminent and popular Victorian novelists, including Thackeray and Trollope, especially during the 1850s and 1860s.

Dickens relished the immediacy of the serial form and the close relationship it allowed him to establish with his readers. Nine of his novels appeared in monthly instalments: Pickwick Papers, Nicholas Nickleby, Martin Chuzzlewit, Dombey and Son, David Copperfield, Bleak House, Little Dorrit, Our Mutual Friend and Edwin Drood. The format was so successful that both Sketches by Boz and Oliver Twist were reissued in parts several years after their first publication, and The Old Curiosity Shop, Barnaby Rudge and A Tale of Two Cities were issued in monthly parts simultaneously with their appearance as weekly magazine serials.