Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist

出版日期: 1839 文学时期: Victorian 类型: Victorian

Oliver Twist is Charles Dickens’s second novel, and is about an orphan boy whose good heart helps him escape the terrible underworld of crime and poverty in 19th-century London. Balancing suspense, melodrama, pathos and humour, it paints a picture of a city tainted by social deprivation.

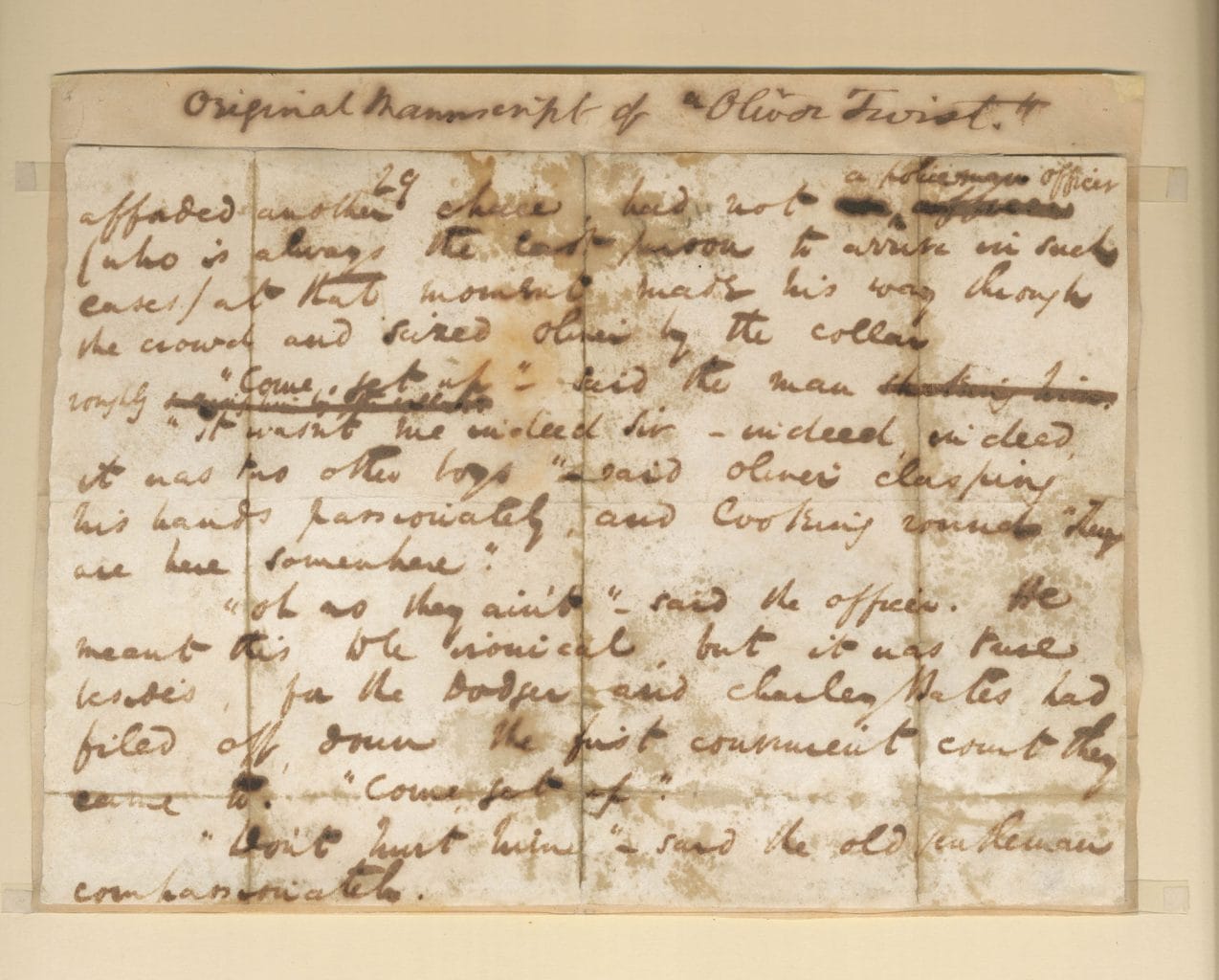

Charles Dickens was just 25 years old when he began writing Oliver Twist. The publisher Richard Bentley had hired the young author to edit a new monthly magazine, Bentley’s Miscellany, and from February 1837, the second issue of the magazine, Oliver Twist began to appear in monthly instalments. At the time Dickens was simultaneously writing two other novels, starting a family, and editing the magazine, and he wrote this, his second novel, at prodigious speed.

Many readers were startled by the sombre tone of the work after the light-hearted comedy of his first novel, The Pickwick Papers. As he grew older Dickens increasingly saw himself as a serious writer with a mission to speak for the poor and powerless. ‘Pray do not … suppose that I ever write merely to amuse, or without an object’, he told one of his critics in 1852.

‘The Parish Boy’s Progress’

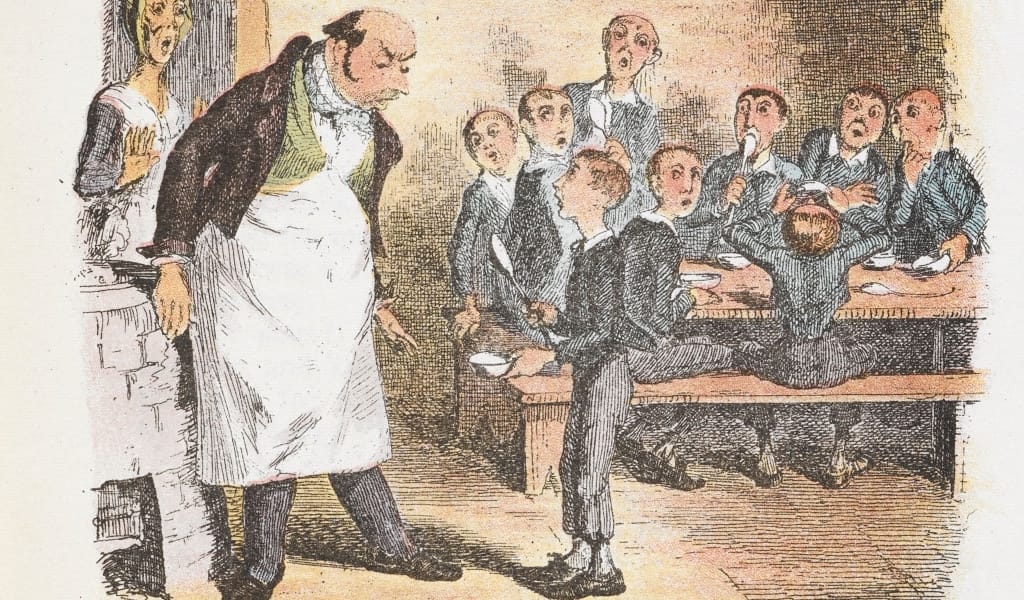

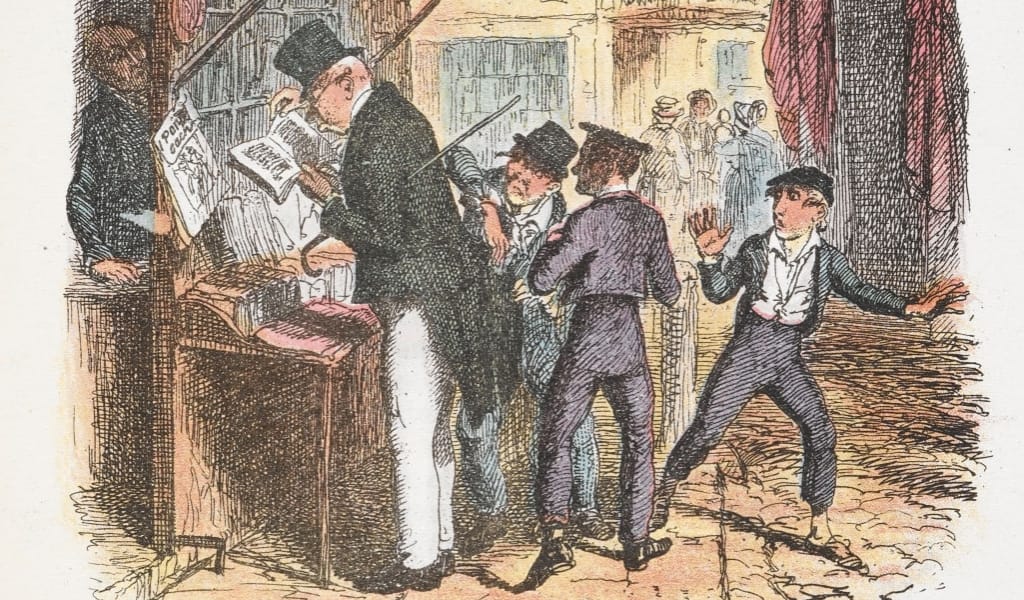

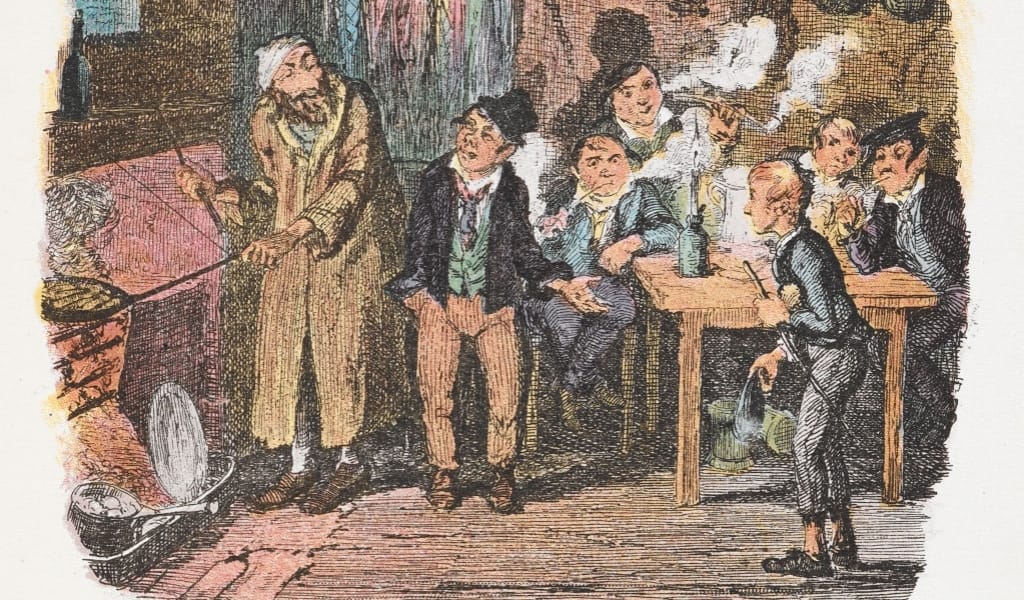

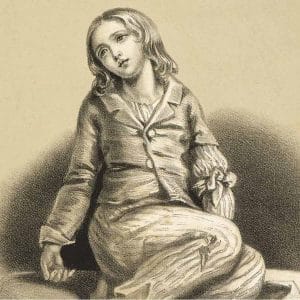

The story of Oliver Twist revolves around the titular orphan, who starts his life in a workhouse. After causing consternation by requesting more food, he is apprenticed to an undertaker, but runs away and becomes part of a pickpocket gang, controlled by the manipulative Fagin. Subtitled ‘The Parish Boy’s Progress’, Oliver Twist was a platform for Dickens to express his concerns about the impact of poverty and the flaws of the workhouse system. One of the author’s motives was to counter the sensational and glamorous depiction of criminals in ‘Newgate fiction’, a popular genre of the 1830s.

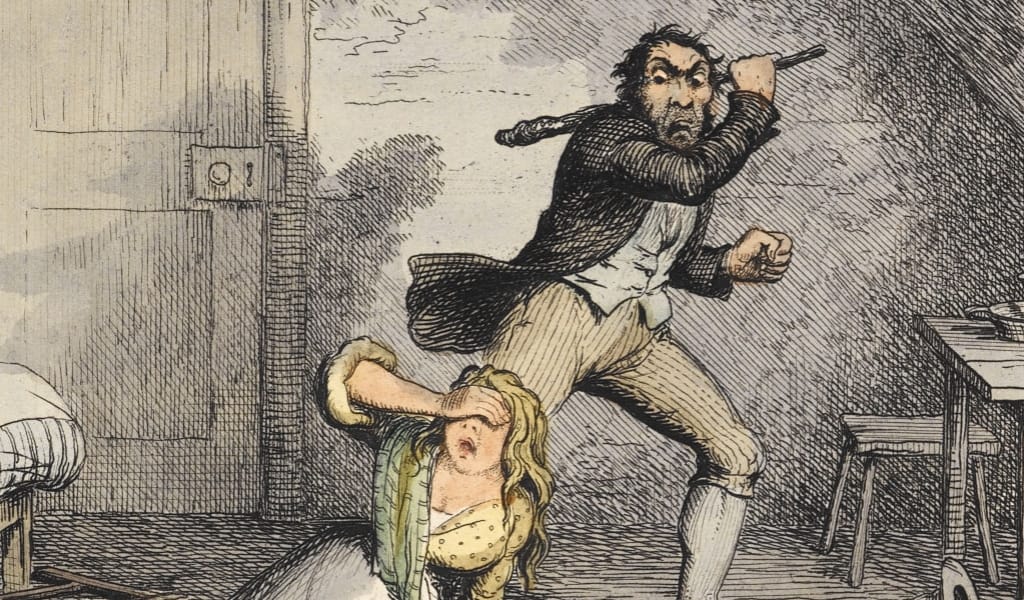

Since its publication, Oliver Twist has been the subject of many adaptations for stage and screen, including the musical Oliver!, and the multiple Academy Award-winning 1968 motion picture. However, the book is generally much darker and bleaker than its many stage and screen adaptations: unlike many Hollywood endings, Fagin is hanged, Oliver’s half-brother steals his money and dies in jail, Sikes murders Nancy before himself meeting a gruesome death, and the Artful Dodger is transported to Australia.

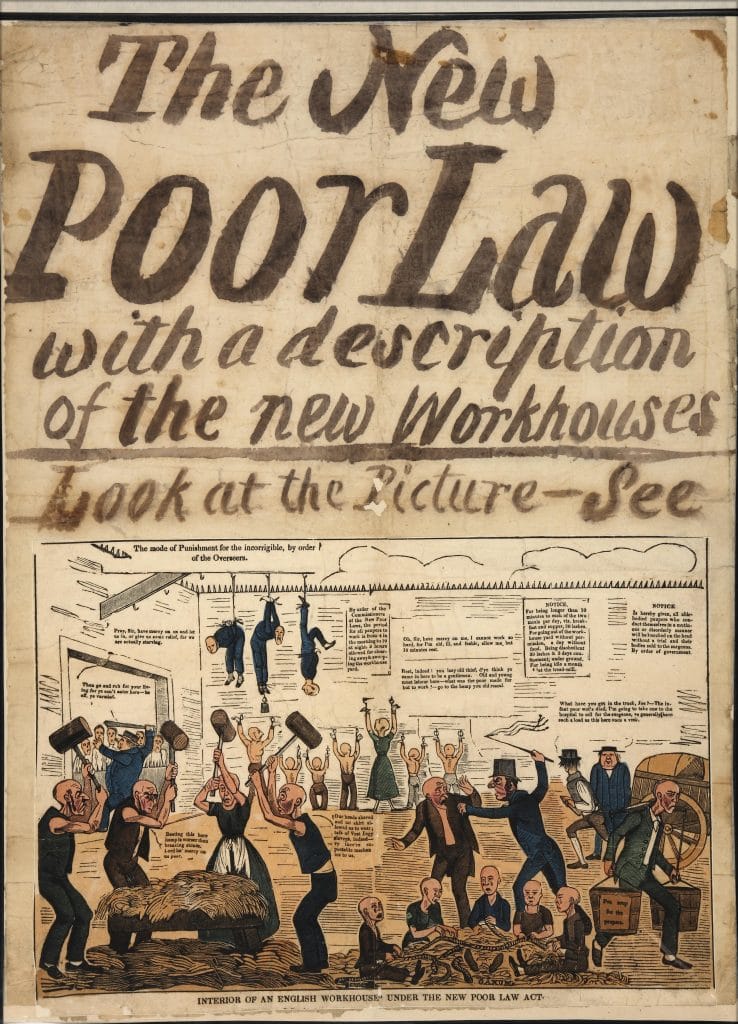

The New Poor Law

Dickens was deeply disturbed by the harsh Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834. The Act, which was met with widespread criticism, was designed to reduce the cost of poor relief by implementing a centralised workhouse system. This meant that relief – clothing and food – was only given in return for gruelling manual labour. Families were split into gender-divided wards, and once in, were prevented from leaving. Conditions in workhouses were so poor that only true desperation drove people to seek refuge there.

The depth of Dickens’s response may well have stemmed from personal experience and observation. After his father was imprisoned for debt, the 12-year-old Dickens spent a humiliating year working in a factory, pasting labels on to blacking bottles. The experience had a lasting impact on the author and informed many of his novels.

London

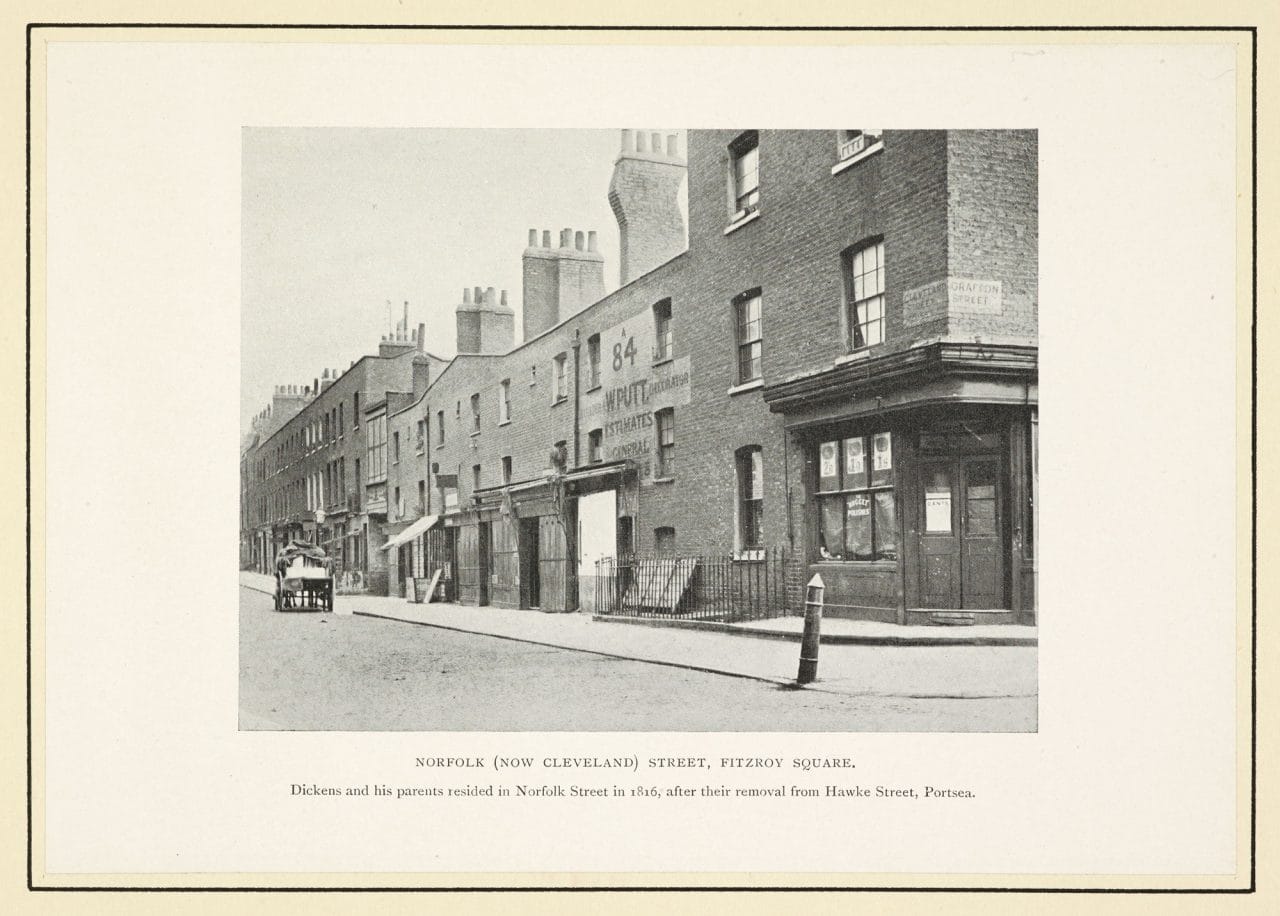

In 1815 Charles Dickens and his family had moved from Portsmouth, on the south coast of England, to 10 Norfolk Street in Bloomsbury, London – the city that became an essential source of inspiration for his later writing. This undated photograph depicts Norfolk Street (now Cleveland Street), where Dickens lived as a child from 1815–17 and as a teenager from 1829. The photograph’s caption, referring to the Dickens’ ‘removal from Hawke Street’, hints at the father’s inability to pay the rent at their previous address and his growing debt problem. By the age of 21 Dickens had lived at 17 different addresses at least.

Like any typical city street, Norfolk Street was a mixture of housing and small businesses. Recently, however, historian Ruth Richardson has discovered something remarkable in connection with Dickens. Just nine doors down from Dickens’s lodgings was a major London workhouse, built in 1775 – arguably the inspiration for the workhouse in Oliver Twist.

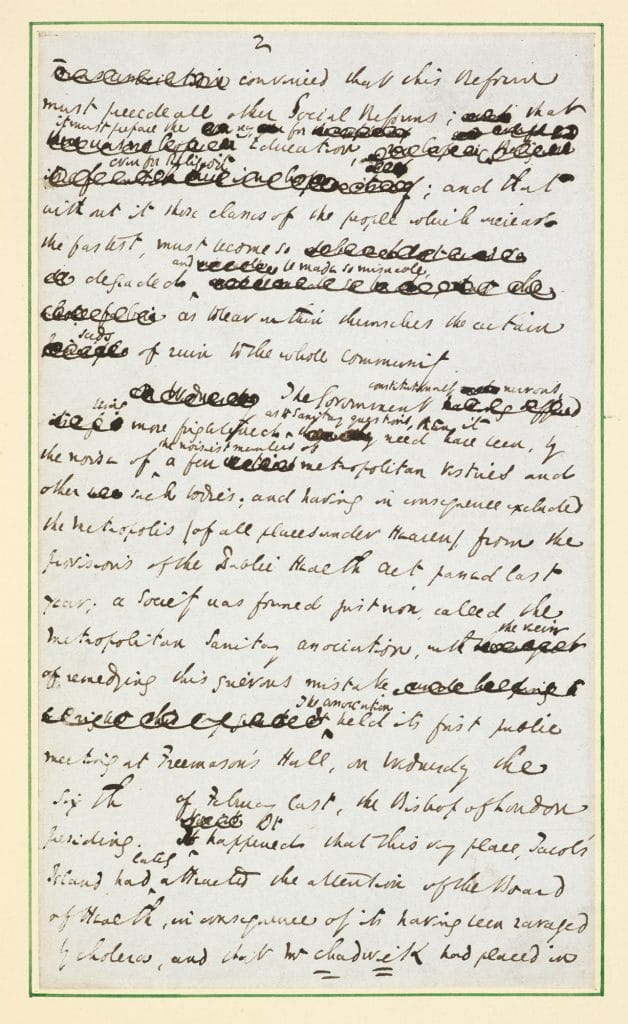

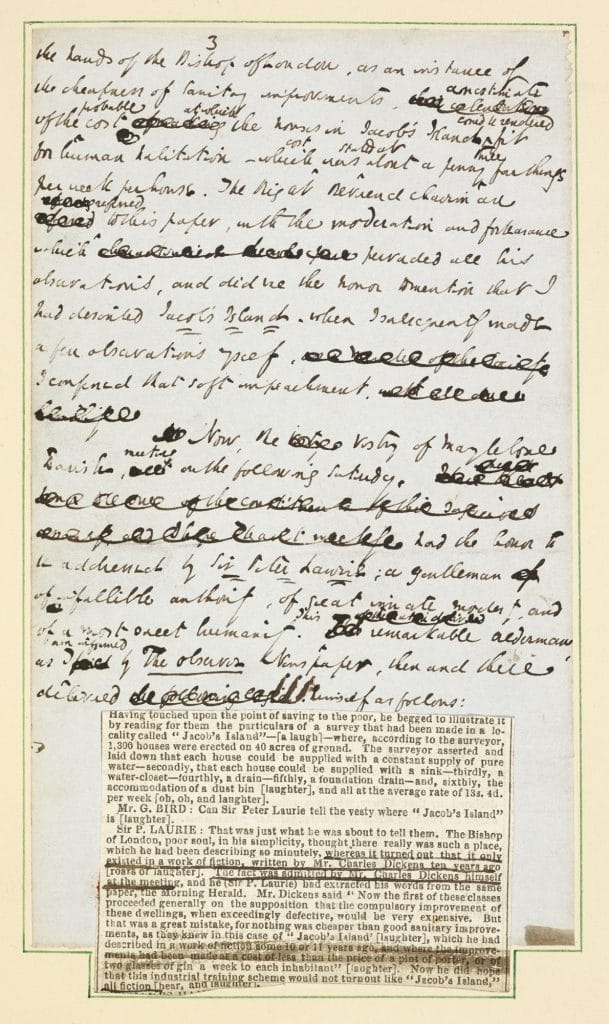

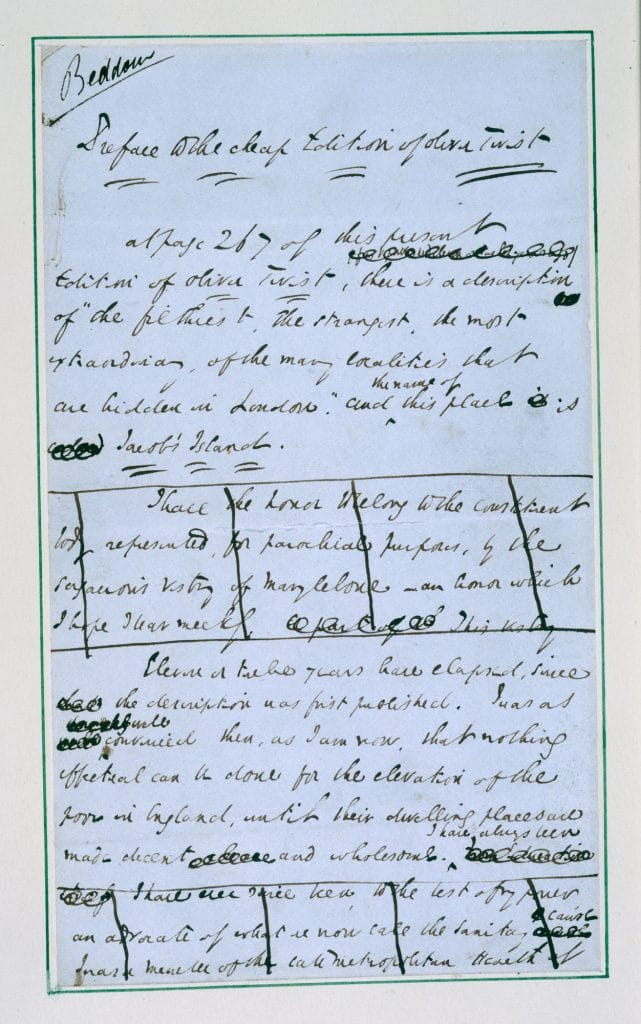

Jacob’s Island

The cheap edition of Oliver Twist was published in 1850, 13 years after its first appearance as a serial in Bentley’s Miscellany. In the Preface to this new edition, Dickens took the opportunity to respond to claims made by the magistrate Sir Peter Laurie that Jacob’s Island, the desolate, decaying neighbourhood where Sikes fell to his death, was simply a figment of Dickens’s imagination. The author stresses that it was in fact an alarmingly realistic depiction of an impoverished Bermondsey slum that had been hit hard by the cholera outbreak of 1849. In just three months over 10,000 people died of the disease in London alone. ‘I was as well convinced then, as I am now’, Dickens writes, ‘that nothing can be done for the elevation of the poor in England, until their dwelling places are made decent and wholesome’.

Extract from chapter 50 of Oliver Twist, introducing Jacob’s Island. Read by Jonathan Keeble.

Dickens was not the only one to draw the public’s attention to the real life squalor of Jacob’s Island. In September 1849, Henry Mayhew wrote an article for the Morning Chronicle, providing shocking details of a visit he made to the London district of Bermondsey.

The cholera outbreak had worsened the already dire living conditions in an area described by Mayhew as ‘a century behind even the low and squalid districts that surround it’, a ‘foul stagnant ditch’ where ‘the air has literally the smell of a graveyard’. As Mayhew reports, the inhabitants of Jacob’s Island drew their drinking water from the same place that human excrement, rotting animal carcasses and mill waste were discarded – which inevitably advanced the spread of disease.

On Mayhew’s suggestion, the editor of the newspaper commissioned an investigation into the living conditions of the working classes in England and Wales. As a result, at least one article appeared every day for the rest of the year and for most of 1850. This dramatically raised the profile of the public health campaign.

Dickens and Cruikshank

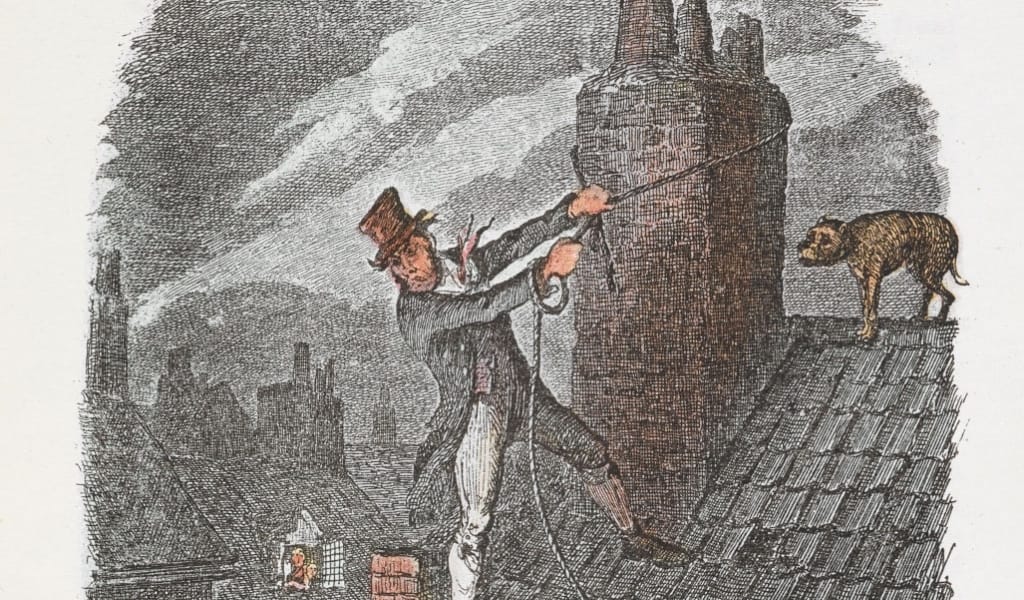

Oliver Twist includes some of the most iconic scenes Dickens ever produced, and these scenes have become inextricably entwined with the illustrations of George Cruikshank.

George Cruikshank (1792–1878) was, from the 1820s onwards, one of Britain’s most renowned satirical illustrators. His subject matter included politicians, the anti-slavery movement, royalty and observations of everyday life. He also produced illustrations for novels, among the most famous of which are those he created for Oliver Twist. Cruikshank provided one black and white plate for each serialised episode of the novel. ‘Oliver Asking for More’ and ‘Fagin in the Condemned Cell’, for example, are said to be among the finest work Cruikshank ever produced – indeed critics have suggested that the illustrations define the episodes they portray every bit as much as Dickens’s own words.