British Library to stage Oscar Wilde event at Hong Kong International Literary Festival, November 2018.

Oscar Wilde’s An Ideal Husband

出版日期: 1899 文学时期: Victorian 类型: Satire 创建: 1895(performed)

An Ideal Husband (1895) is the third of Oscar Wilde’s society comedies after Lady Windermere’s Fan (1892) and A Woman of No Importance (1893). Underneath a surface of frivolity and witty exchanges, Wilde explores the serious question of the relationship between political power and personal morality. After laughing at others, Wilde taught Victorian theatregoers to turn their laughter towards themselves. The play premiered at the Haymarket Theatre in London on 3 January 1895 to popular acclaim, and ran for over one hundred performances. An Ideal Husband delighted and continues to delight audiences with its mixture of scandal and humour, melodrama and satire.

Synopsis

The play opens at a dinner party at Sir Robert Chiltern’s house in the fashionable Grosvenor Square in London. Lady Markby arrives with an unexpected guest, the witty and ambitious Mrs Cheveley. It transpires that Mrs Cheveley went to school with Sir Robert’s wife, Mrs Chiltern. Mrs Cheveley has returned from Vienna to blackmail Sir Robert, a promising Foreign Office politician. Sir Robert’s wealth, and therefore his career, was founded on a financial reward for selling a cabinet secret about the Suez Canal Company. Throughout the play, Sir Robert goes to great lengths to hide his secret – and the stain on his character – from his wife. Mrs Chiltern puts her ‘ideal husband’ on a pedestal and Sir Robert fears the loss of her love. Mrs Cheveley, eager to benefit from Sir Robert’s situation, outwits him several times before being outwitted herself in the final act of the play. Wilde demonstrates that none of the characters are faultless; indeed even the outwardly flawless Mrs Chiltern makes a foolish mistake of her own by writing a compromising letter to Lord Goring after discovering her husband’s misdemeanour.

Fashion and modernity

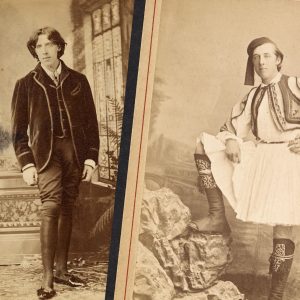

In An Ideal Husband, Wilde contrasts the marriage of Sir Robert and Mrs Chiltern with the growing affection between Sir Robert’s sister Mabel and his friend Lord Goring. The flirtatious relationship between Mabel Chiltern and Lord Goring does not have the same high moral expectations that threaten to destroy the relationship of the married couple. Lord Goring dresses with impeccable taste, but has no useful occupation, much to the disappointment of his father. He is ‘a flawless dandy’. When Lord Caversham complains that his son ‘leads such an idle life’, Mabel comes quickly to Lord Goring’s defence: ‘How can you say such a thing? Why, he rides in the Row at ten o’clock in the morning, goes to the Opera three times a week, changes his clothes at least five times a day, and dines out every night of the season’. The characters of Mabel and Lord Goring are perhaps the closest to Wilde himself. Wilde embraced decadence, dressed flamboyantly according to aesthetic principles and promoted a way of life that others emulated.

In the second act, Mabel announces that she needs to go to a rehearsal for a performance where her role is to stand on her head ‘in some tableaux’. Lady Markby feels that Mabel is ‘a little too modern, perhaps’, for ‘nothing is as dangerous as being too modern. One is apt to grow old-fashioned quite suddenly’. Mabel adds that the performance is ‘for an excellent charity: in aid of the Undeserving, the only people I am really interested in’. Through Mabel, Wilde mocks the charitable giving of the English upper classes and their distinction between the deserving and the undeserving poor. As outlined in his 1891 essay, ‘The Soul of Man under Socialism’, Wilde believed that charity failed to address the fundamental causes of poverty and masked deep-rooted social inequalities.

What do the manuscripts tell us about Wilde’s creative process?

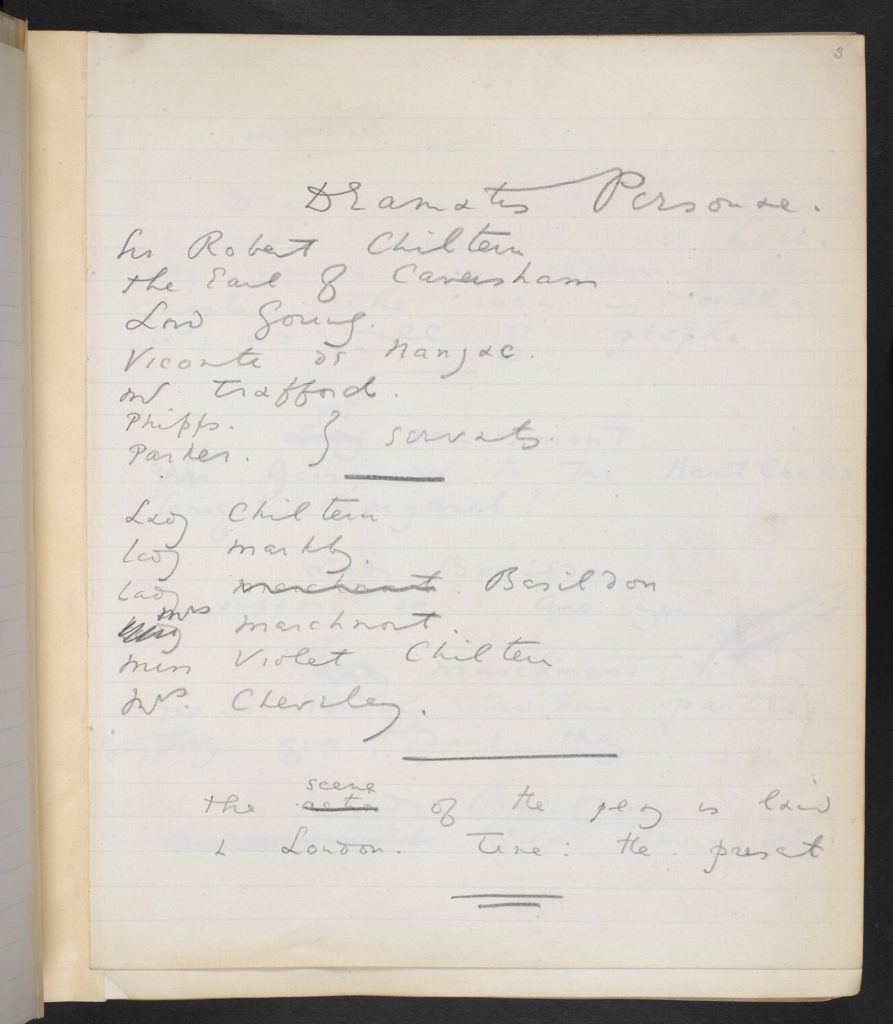

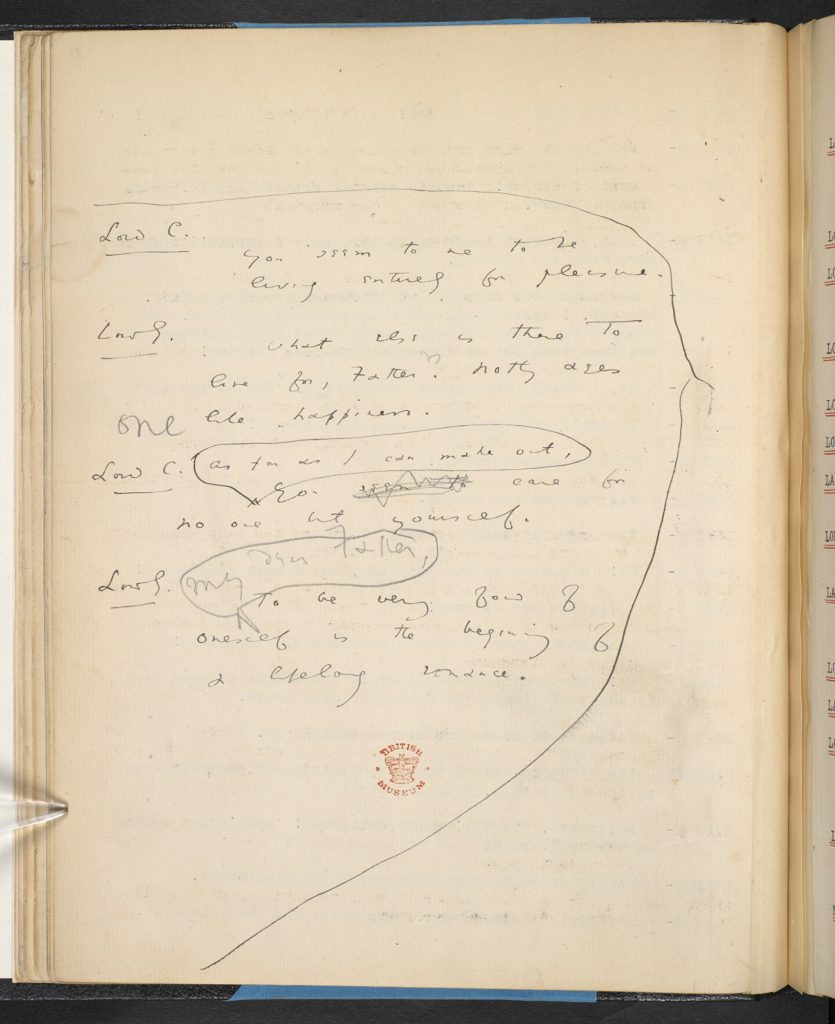

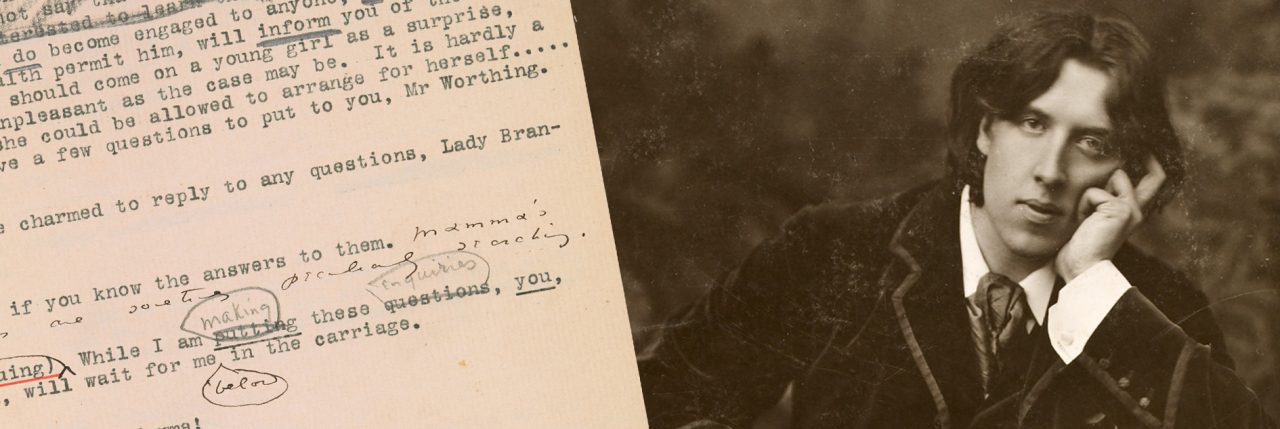

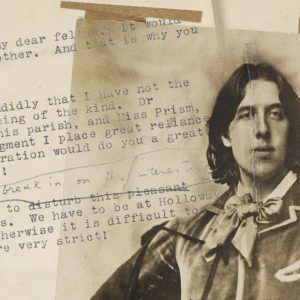

In the summer of 1893, Wilde rented a house with his lover Lord Alfred Douglas at Goring-on-Thames. Wilde named the character of Lord Goring after Goring-on-Thames, where he began writing An Ideal Husband. He finished writing the four-act play at St James’ Place in London. A note in Wilde’s own hand at the beginning of the manuscript draft shown above (Add MS 37946) states: ‘copy to be sent to 10. St James’ Place by Saturday’, showing that this version was probably sent to the typist before it was returned to his home address with the typescript copy. Wilde developed his characters and perfected the plot and dialogue over several drafts.

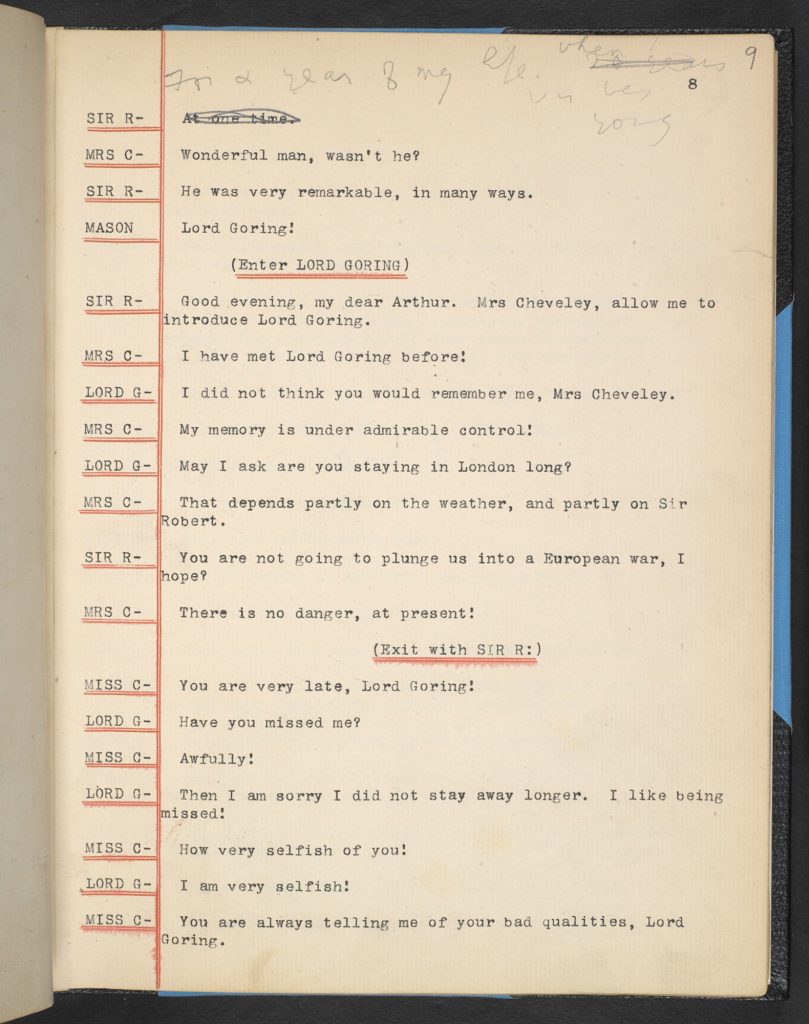

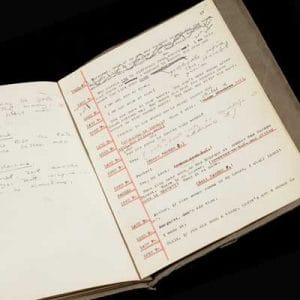

The manuscript and typescript drafts differ from the play script that was granted a performance licence for the Haymarket Theatre by the Lord Chamberlain in January 1895, and from the version published in 1899. We can see that Wilde composed the dialogue first because there are very few stage directions in the draft versions. The plot and all of the main characters are in place, but Mabel Chiltern, Sir Robert Chiltern’s sister, is called Violet in this version. Wilde edited his own handwritten draft in pencil and he used the left-hand pages of the notebook to write lengthier additions and revisions.

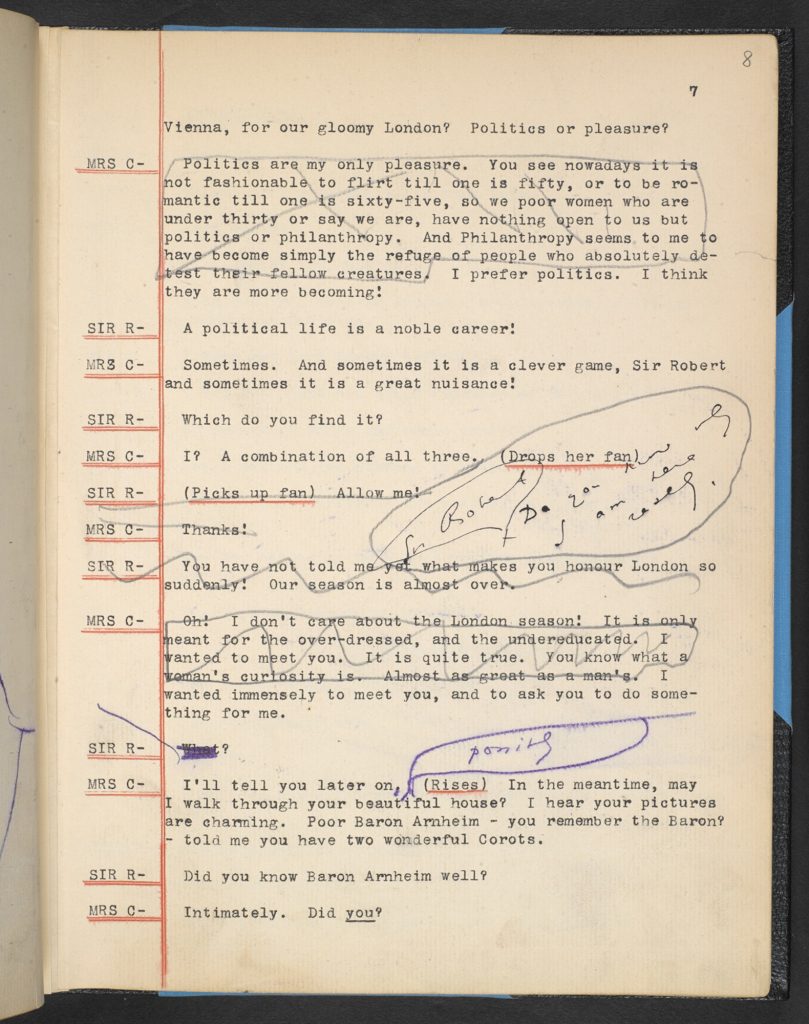

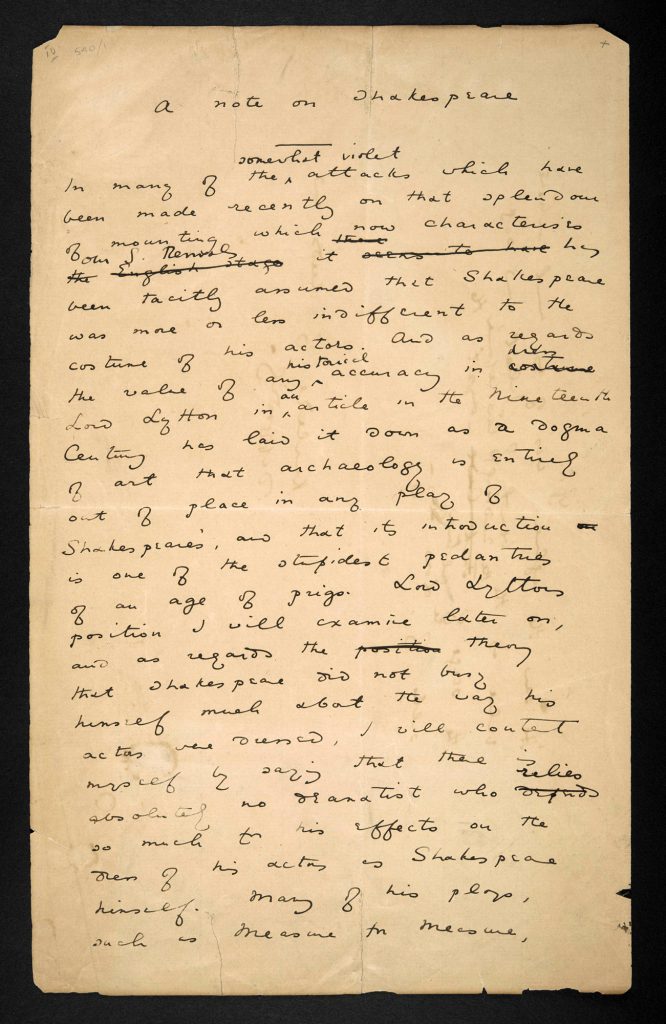

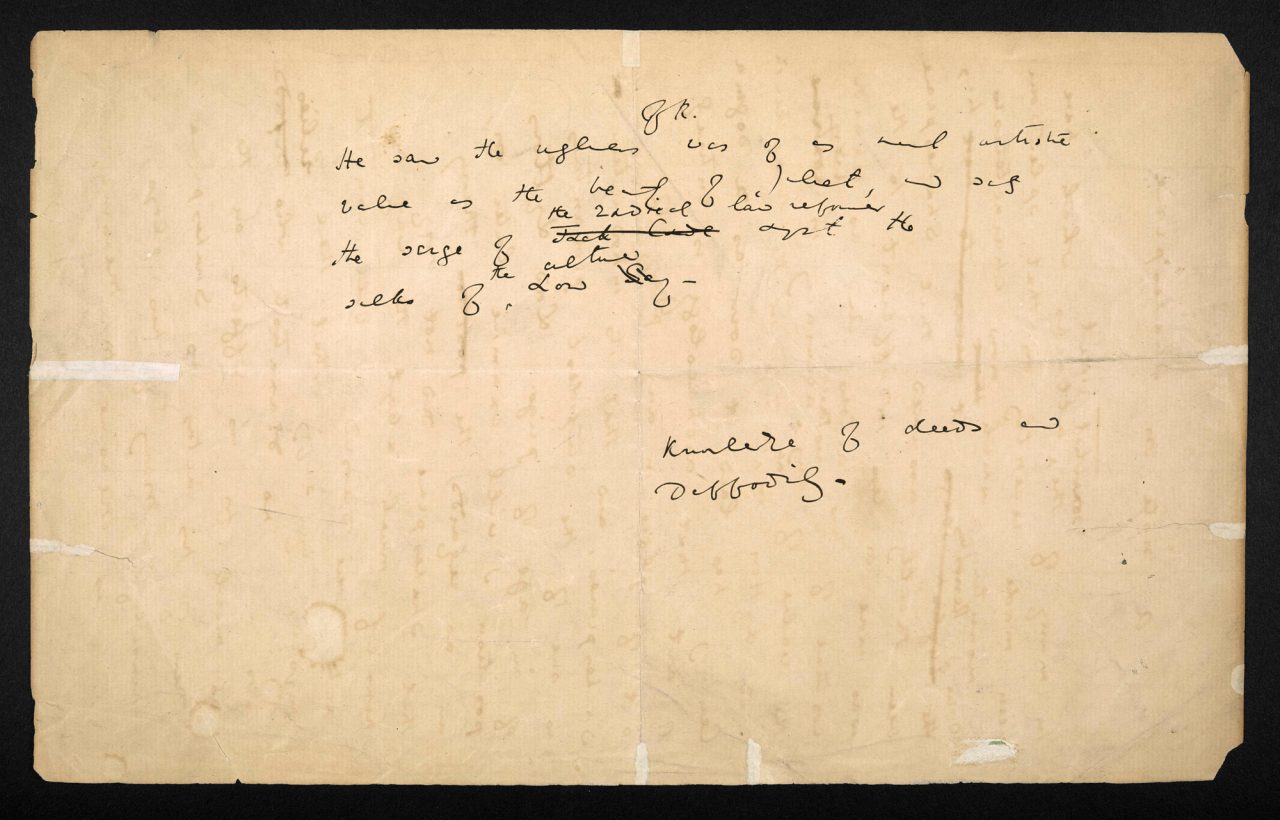

Wilde might have used the typewritten version pictured above (Add MS 37947) in early rehearsals before making further changes after hearing his words recited by actors. Wilde makes many changes throughout this draft, cutting some sections of speech, and adding large pieces of new dialogue. The script shows notes in pencil, purple pencil, and black ink, showing that Wilde worked through this draft in multiple sittings.

Why was the play not published until 1899?

Wilde was arrested on 6 April 1895 on a charge of ‘gross indecency’ for homosexual activity under Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act (1885) while An Ideal Husband continued to play to full houses at the Haymarket Theatre. Wilde was imprisoned for two years’ hard labour. After his release from prison on 18 May 1897, Wilde sailed immediately for France, where he lived until his death on 30 November 1900. Both An Ideal Husband and The Importance of Being Earnest were published in 1899.

The published version is markedly different from the manuscript drafts. Wilde added elaborate stage directions which do not appear in either the handwritten or the typewritten drafts. The written descriptions of characters are transformed on stage into the actions and the costumes of the characters themselves. In the published play, Wilde introduces characters by evoking works of art in the minds of a knowledgeable reader. Lady Chiltern is ‘a lady of grave Greek beauty’, while Mabel Chiltern is ‘really like a Tanagra statuette’, a Greek terracotta figurine of the 4th century BCE with naturalistic features and colours. Mrs Cheveley is ‘a work of art, on the whole, but showing the influence of too many schools’, perhaps anticipating the duplicitous nature of her character.

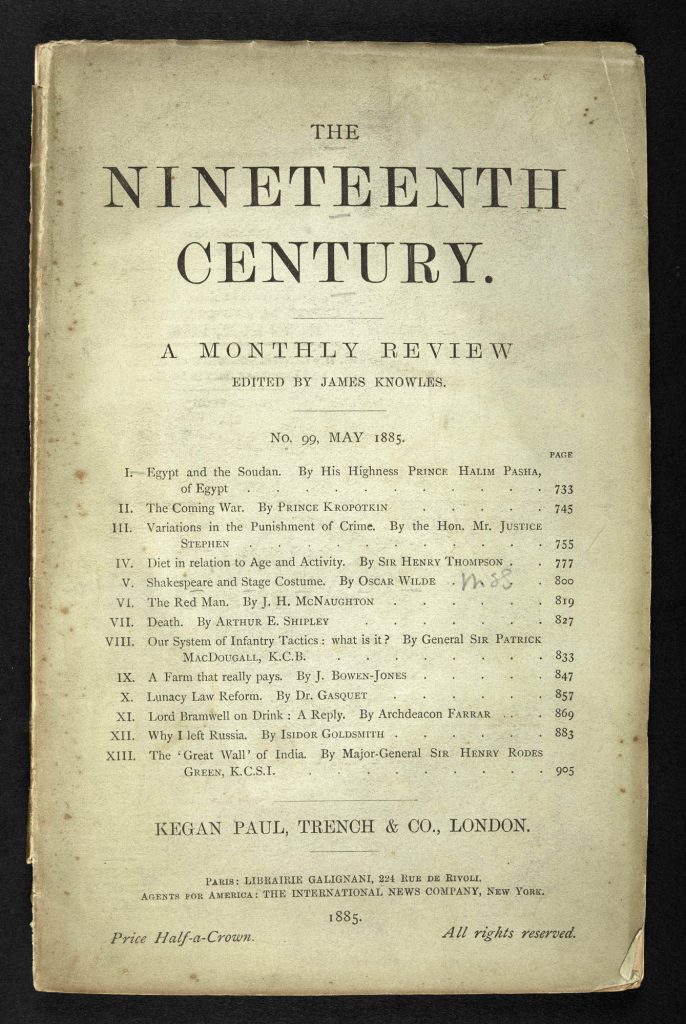

In an essay on ‘Shakespeare and Stage Costume’ for The Nineteenth Century (1885), Wilde brought together a range of evidence from Shakespeare’s plays and productions to show that the Renaissance dramatist placed high importance on costume design. Wilde’s own published play contains descriptions of furniture, costumes and postures that would inform future productions of his work. For Wilde, ‘the stage is not merely the meeting place of all the arts, but is also the return of art to life’. [1]

Written By: Catherine Angerson

Catherine Angerson is a Curator of Modern Archives and Manuscripts at the British Library, where she works with literary and historical papers from the 17th to the early 20th centuries. Her doctoral research at Birkbeck, University of London focuses on the reception of German literature and ideas in Britain.

The text in this article is available under the terms of a Creative Commons License.